“Here lions threat, there elephants will range, And camel-necks to vapoury dragons change.”

– In Honor of Mr. Howard (Howard’s Ehrengedächtnis) by Wohann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1820

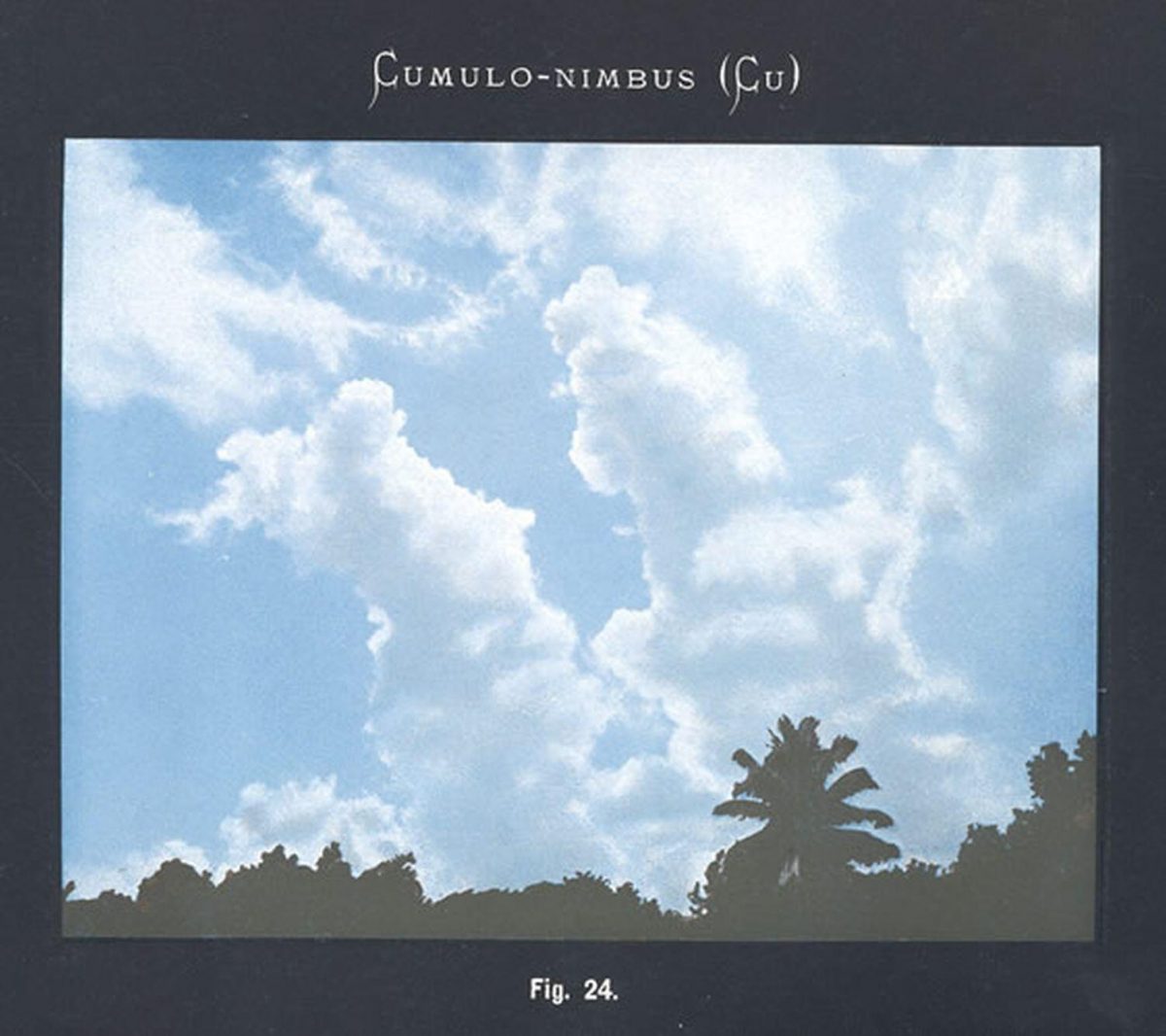

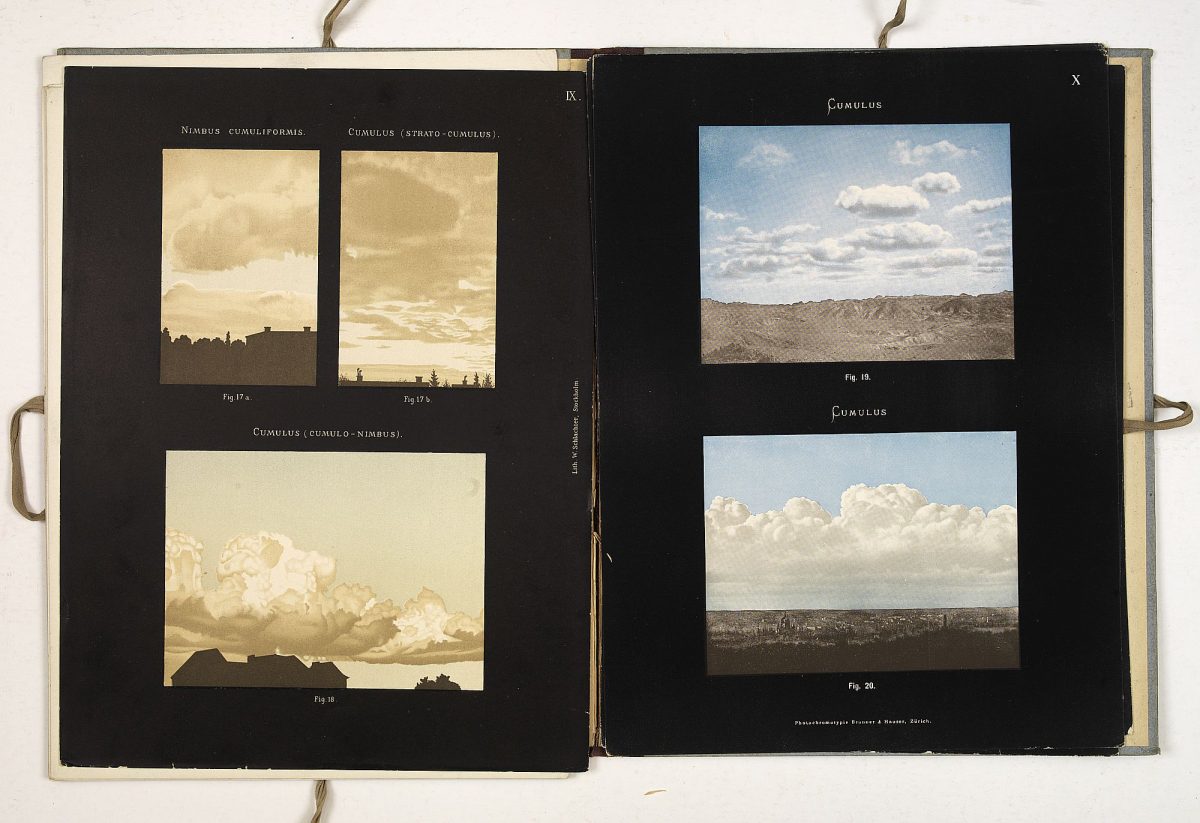

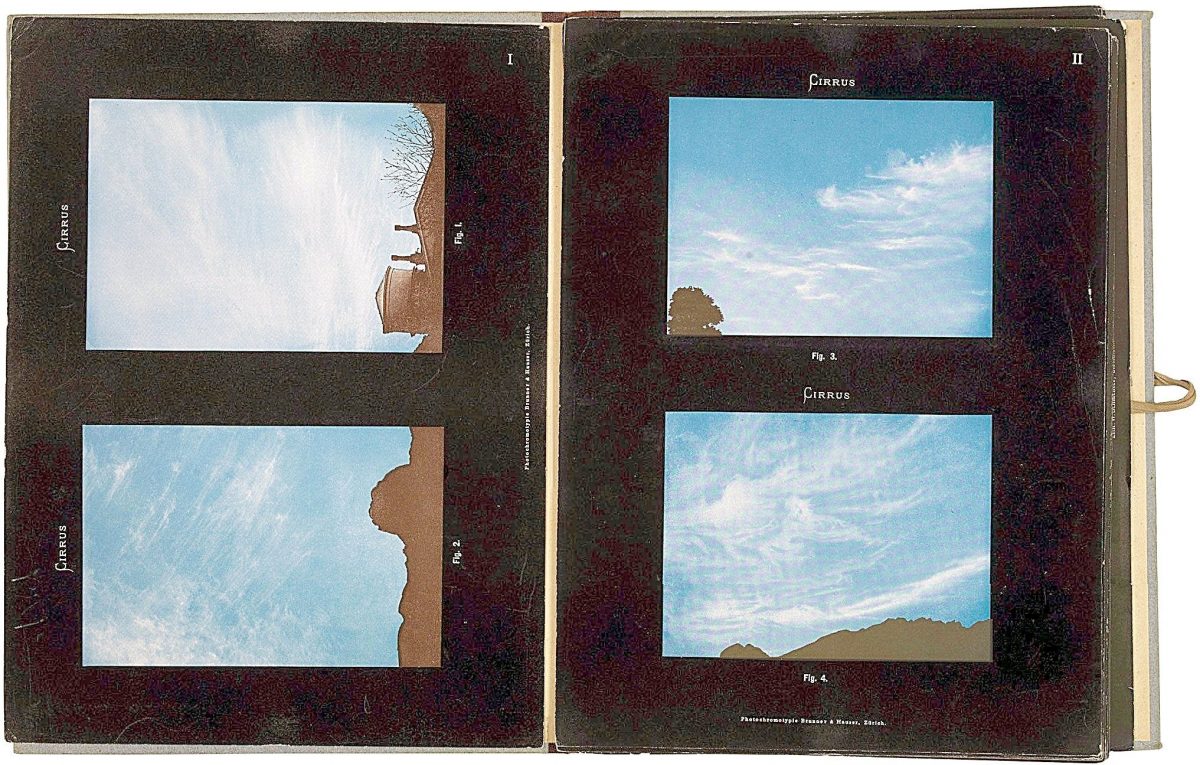

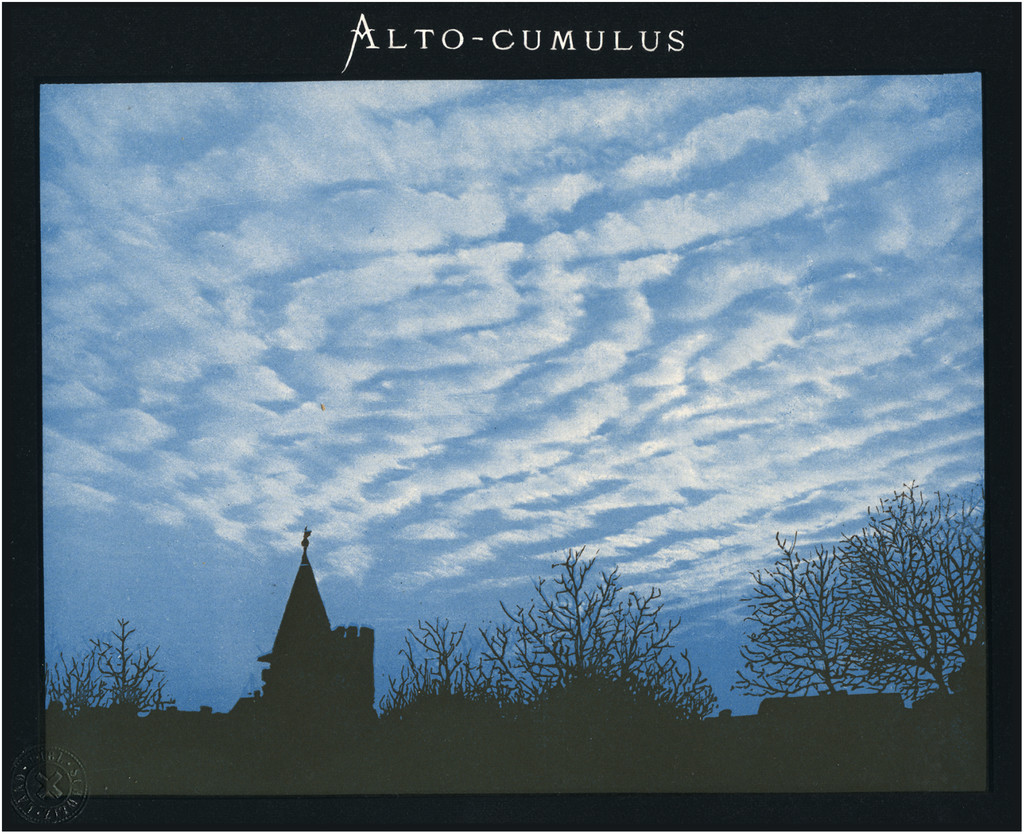

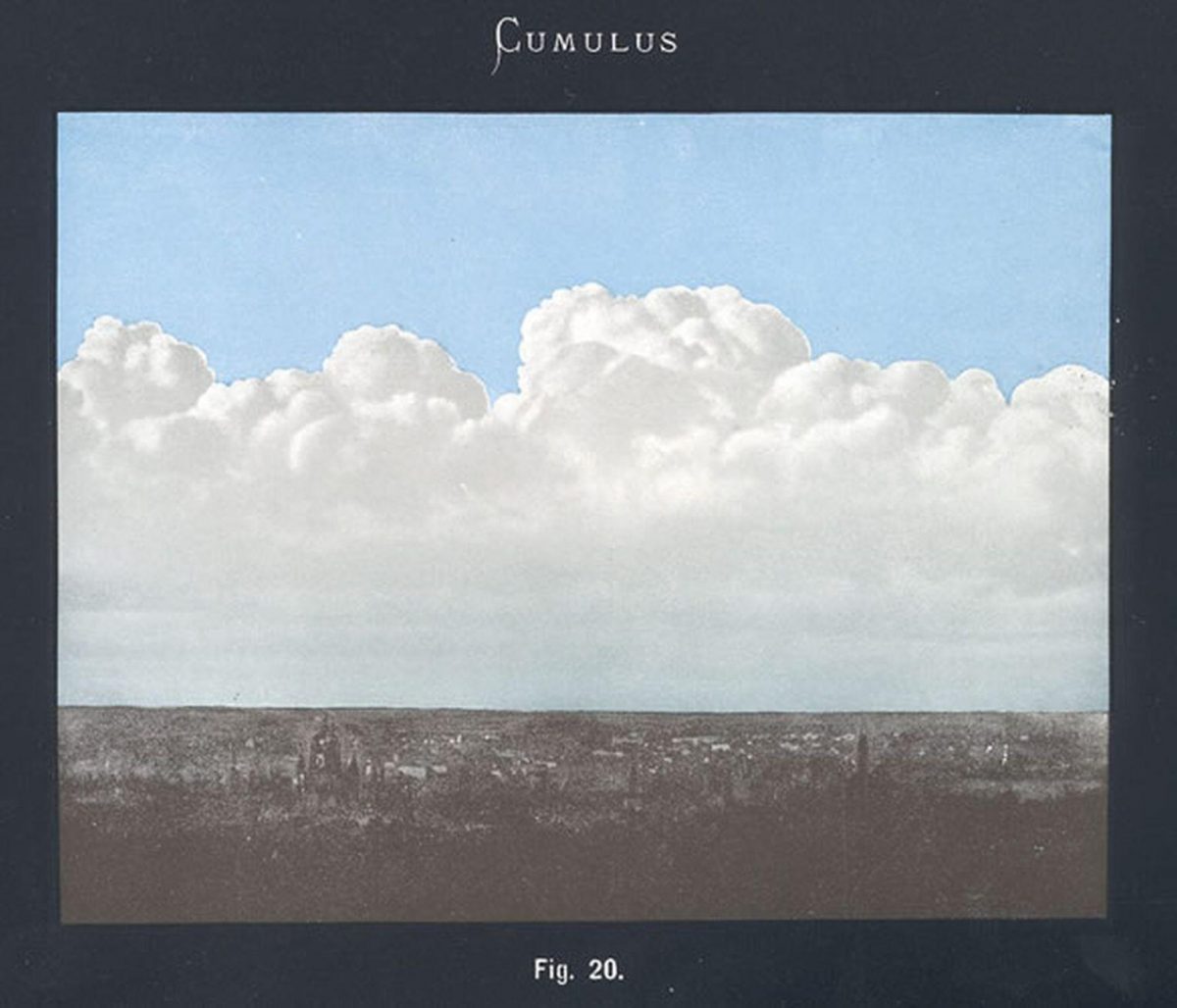

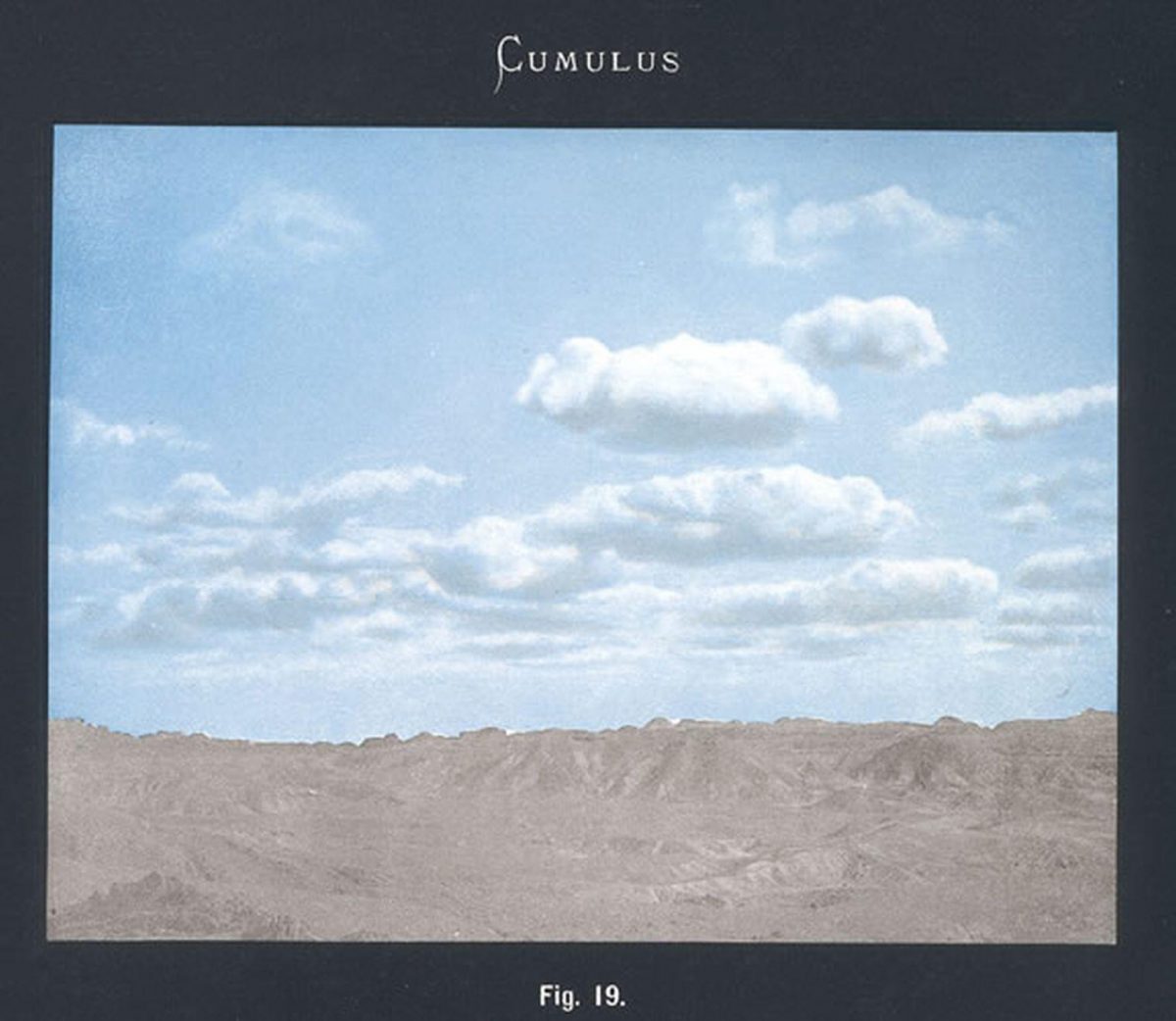

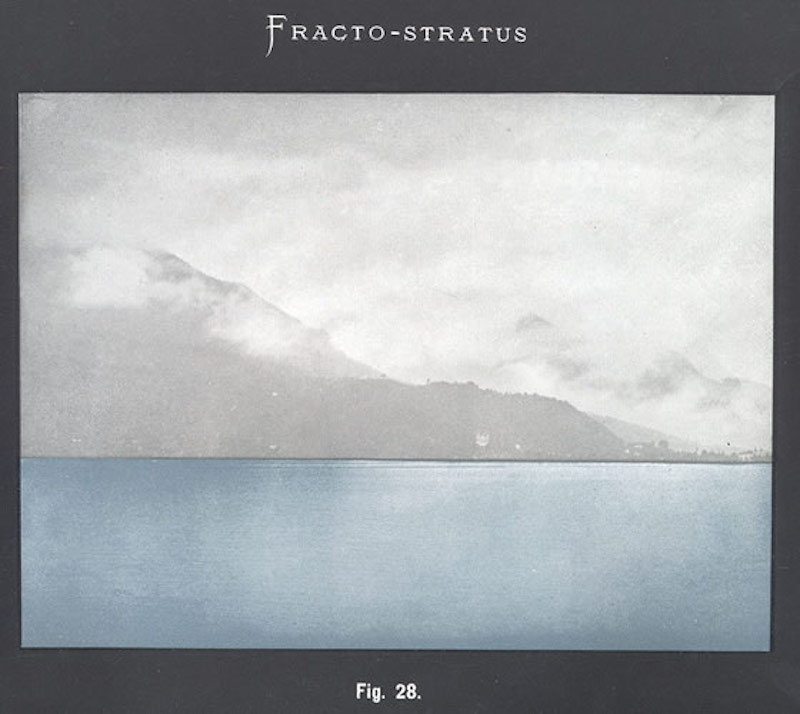

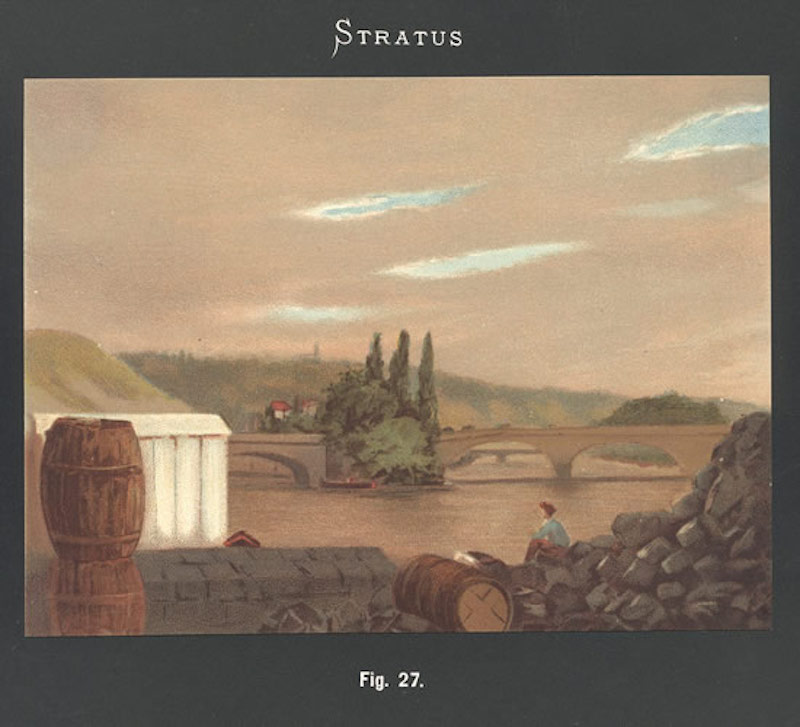

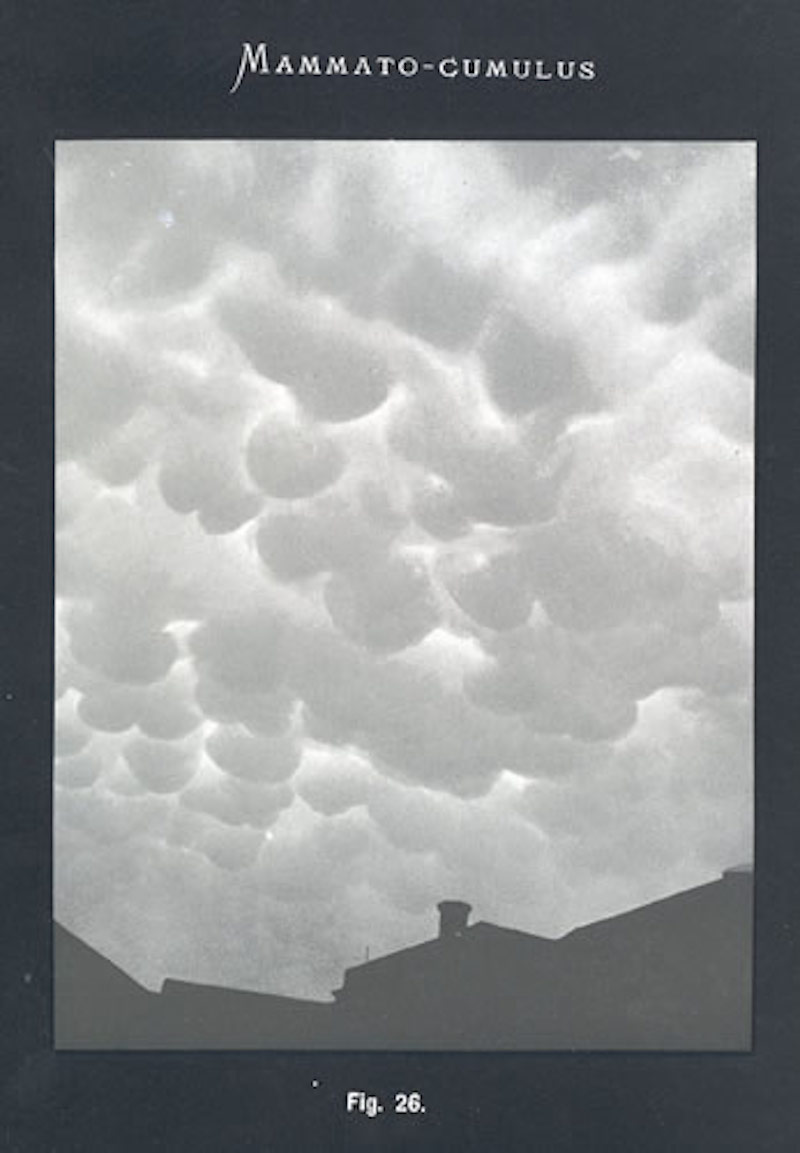

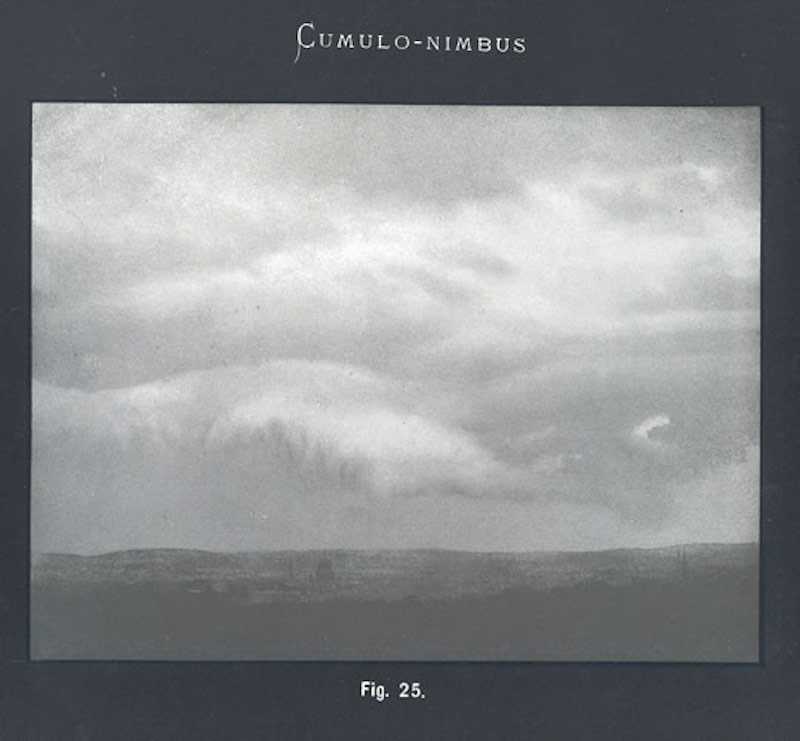

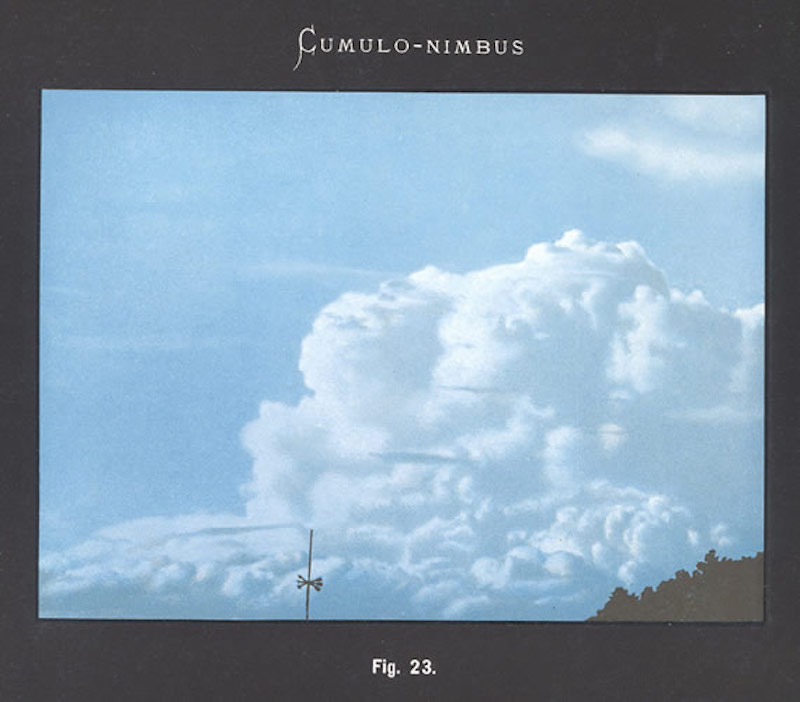

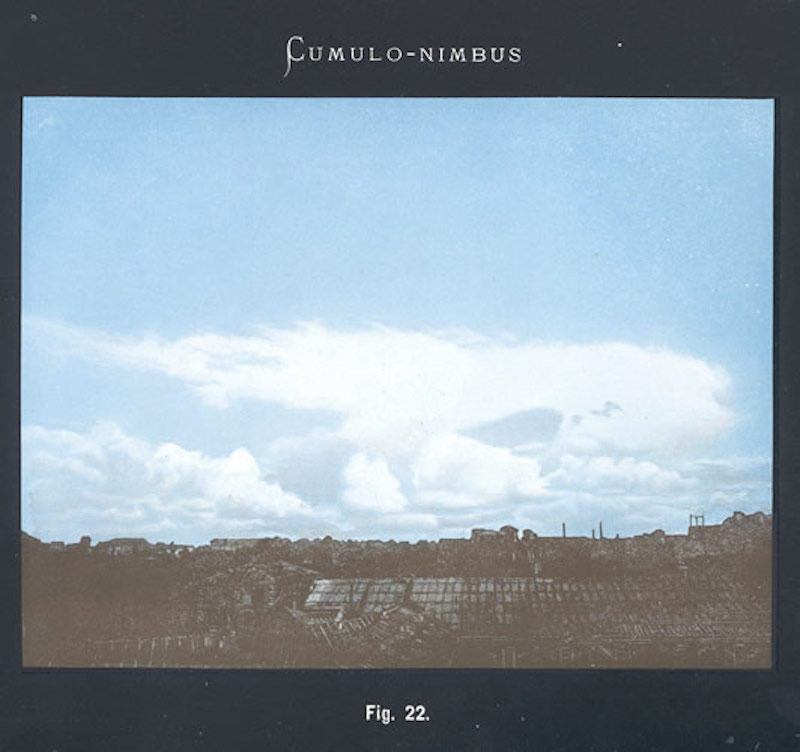

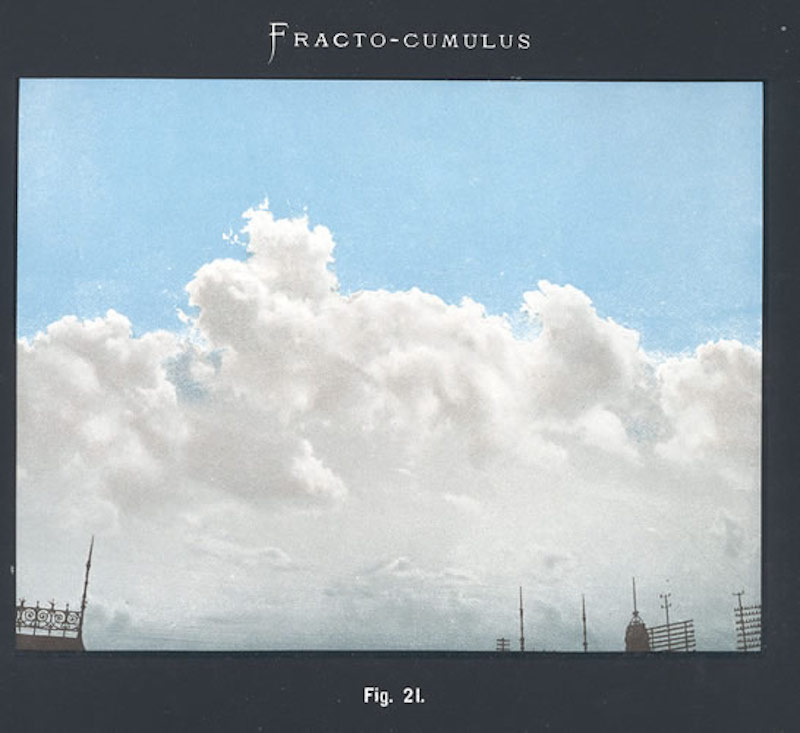

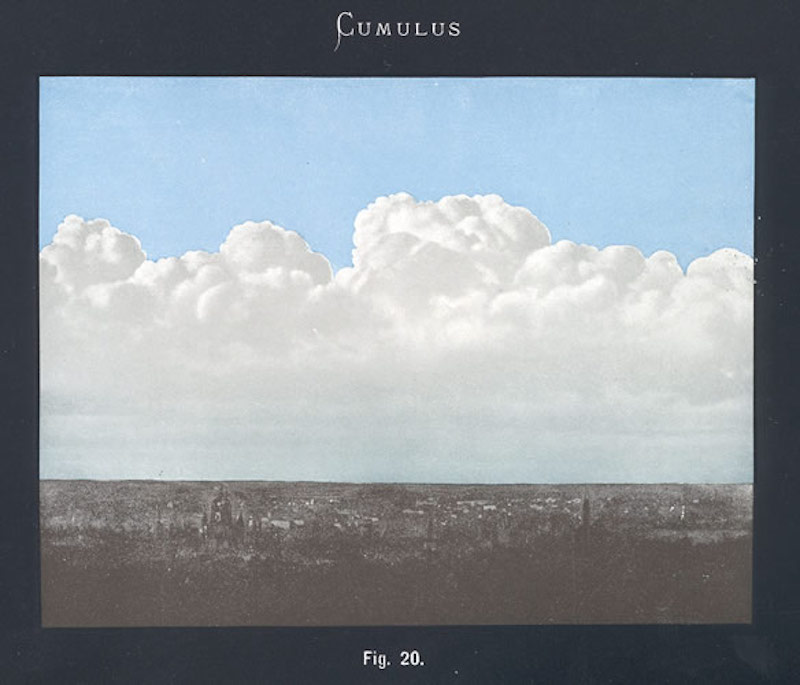

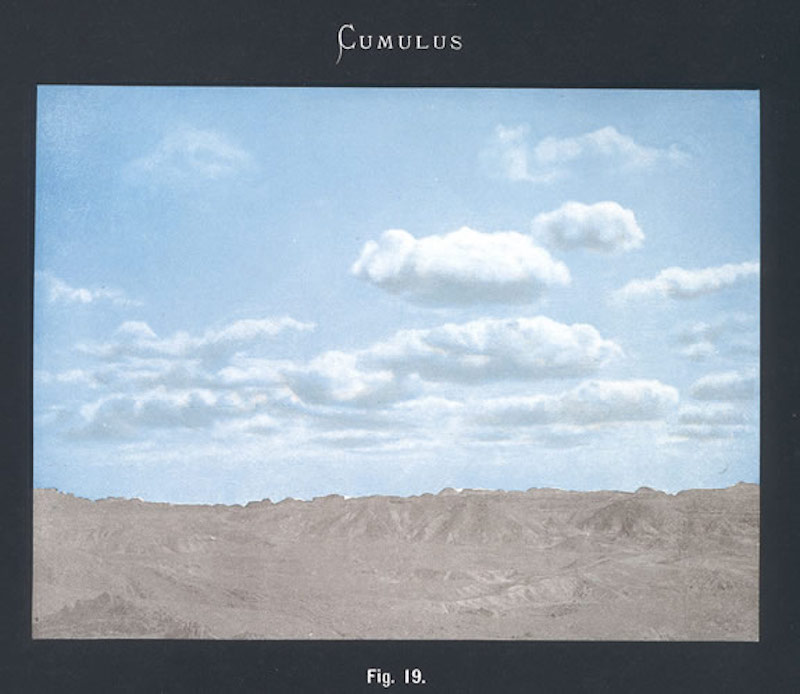

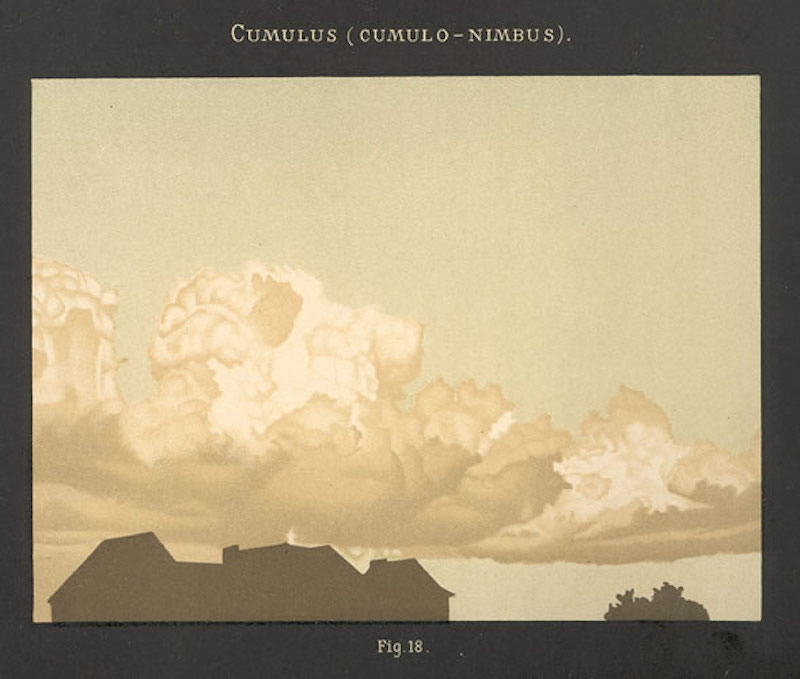

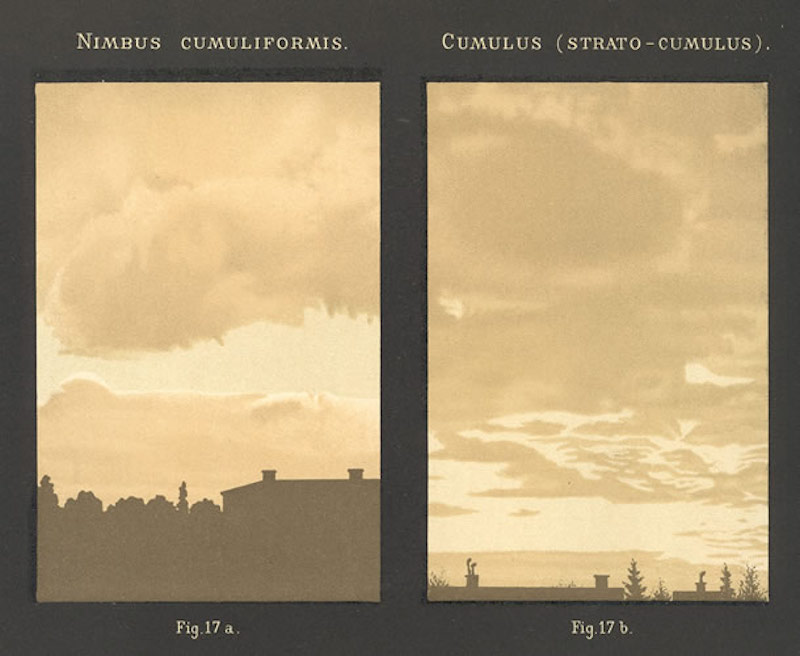

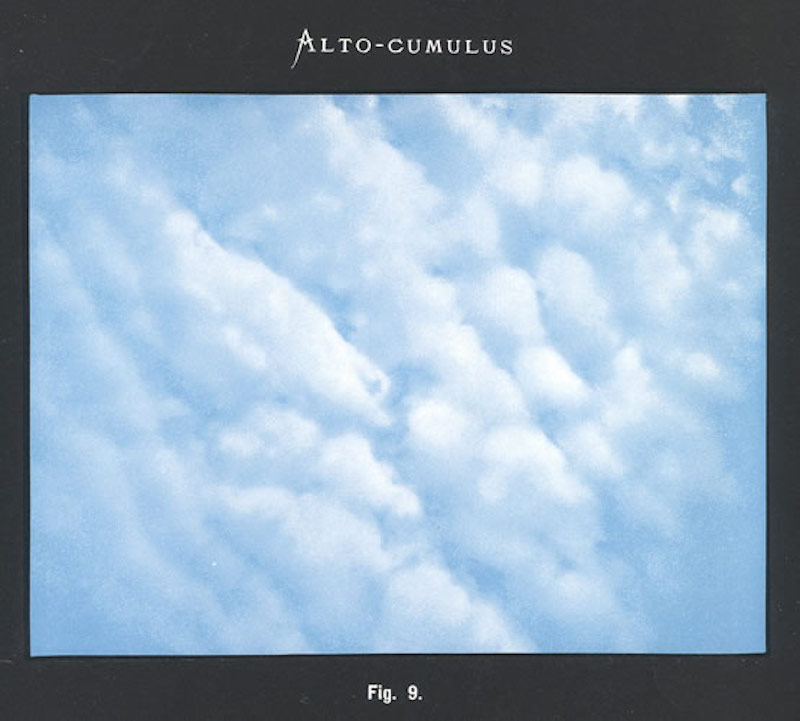

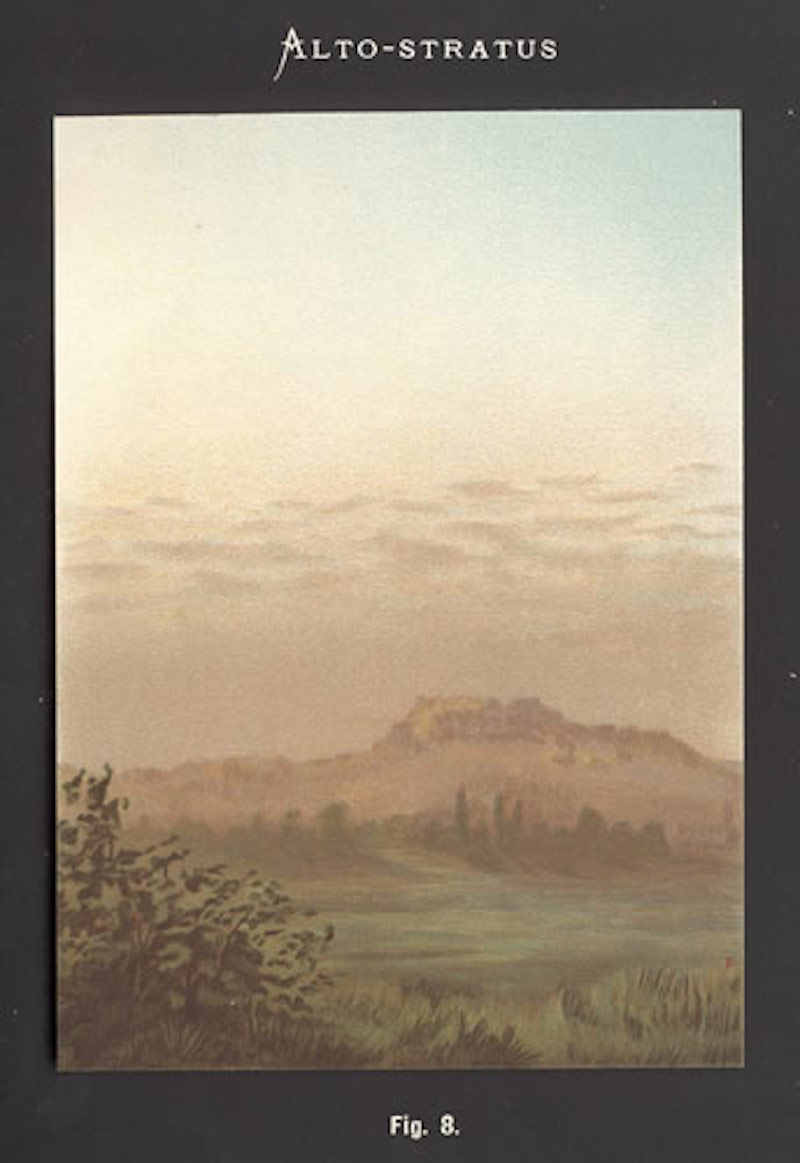

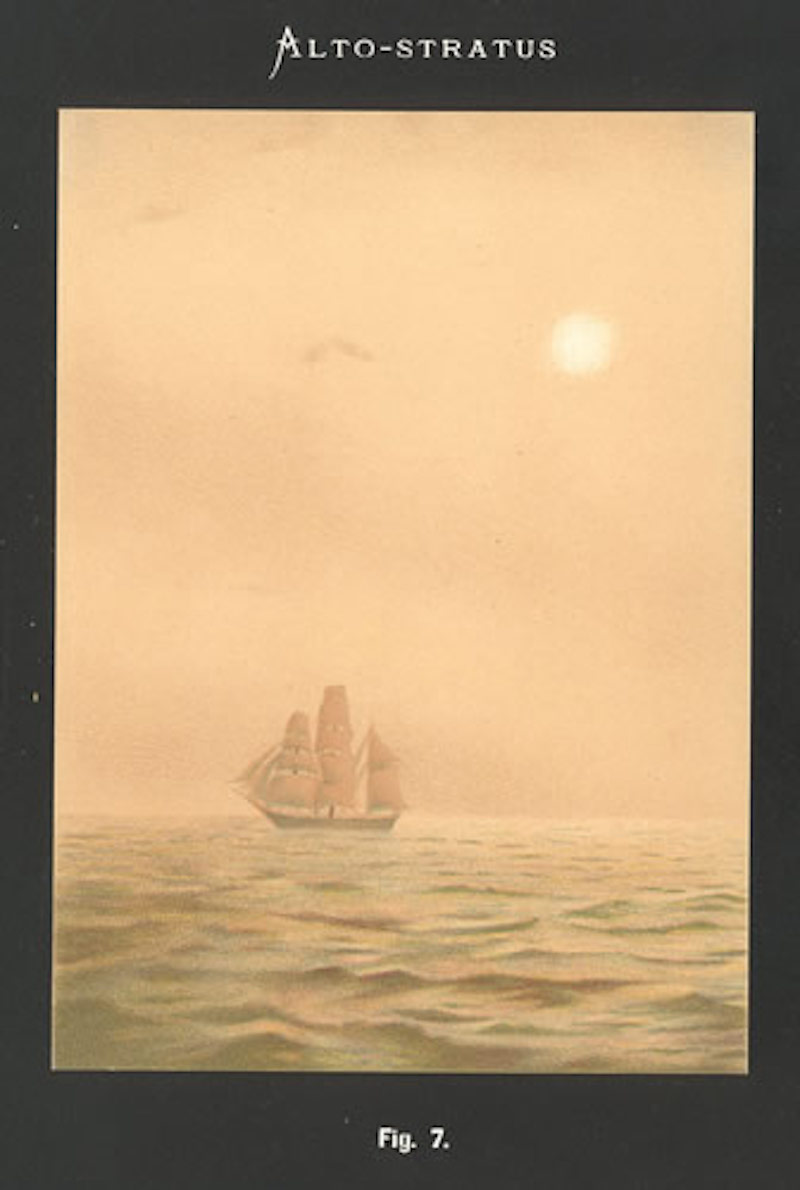

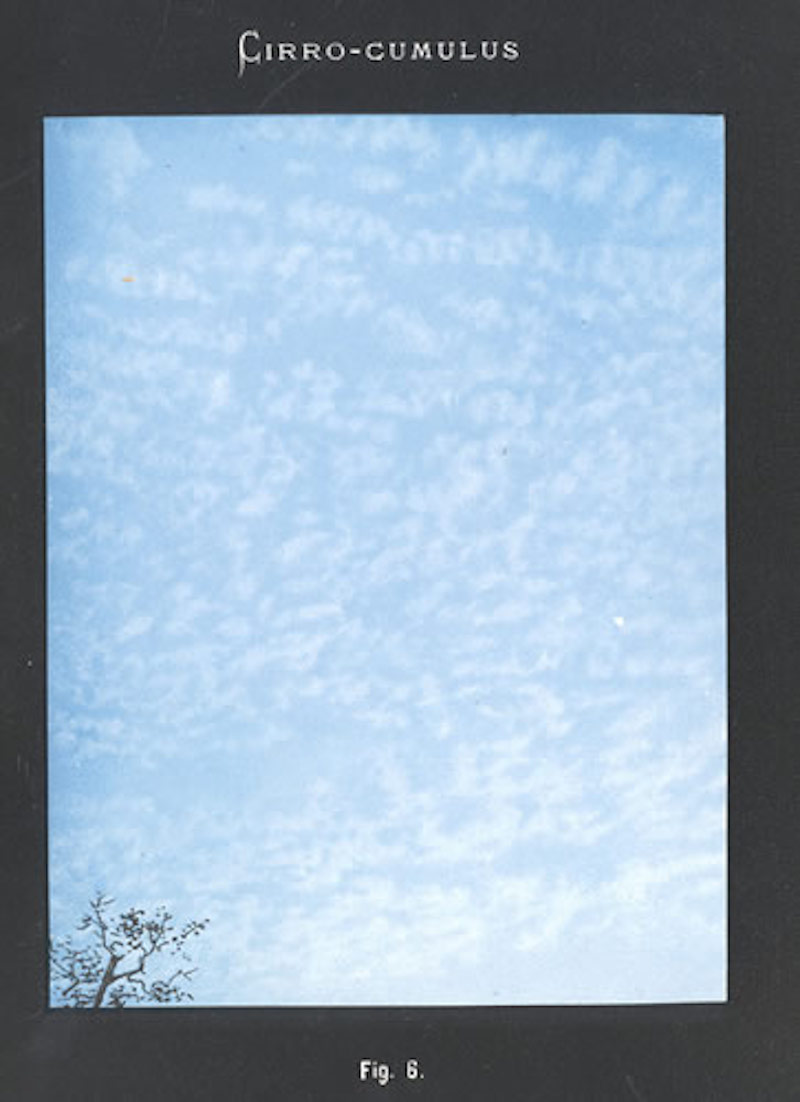

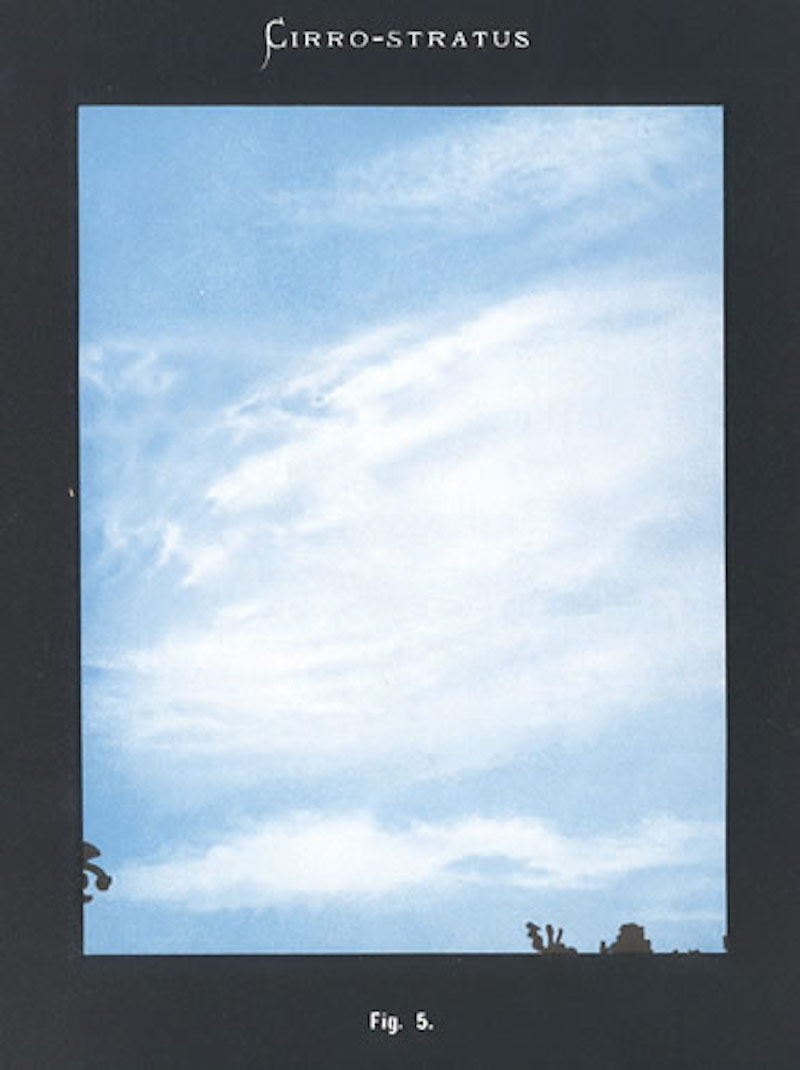

The Atlas international des Nuages (International Cloud Atlas; Internationaler Wolkenatlas) was published in Paris, France, by Gauthier-Villars et fils in 1896. This pictorial atlas contained 14 illustrations on 14 printed color plates. A mix of photographs (chromotypographs) and pantings, the text was in English, French, and German.

The Atlas broke new ground, introducing a universal language of cloud identification, and embraced emerging technologies – the page on cirrus clouds was the first type of cloud illustrated from a color photograph.

Just as British chemist Luke Howard (28 November 1772 – 21 March 1864) had done when he named clouds, classifying them into 7 types, the International Cloud Atlas was a huge step in increasing our understanding of the skies.

Cloud research is ongoing. In 2019, World Meteorological Organization Secretary-General Petteri Taalas reaffirmed the importance of understanding clouds: “If we want to forecast weather we have to understand clouds. If we want to model the climate system we have to understand clouds. And if we want to predict the availability of water resources, we have to understand clouds.”

The Atlas was a product of art and science. 1874 was the year of the first International Meteorological Congress. Cloud classification was high on the agenda. How could traders and travellers more easily identify the weather and track it across international borders? How could weather be more accurately forecast? During the succeeding 20 years multiple proposals were advanced in many countries by a large number of scientists and researchers.

In 1887 Scottish meteorologist Ralph Abercromby (11 February 1842 – 21 June 1897) wrote of “the impossibility of expressing the varying forms of clouds in words”. After a decade travelling the world observing clouds, Abercromby “found that though some forms of cloud were almost universally assigned the same name, others – especially the lower clouds – received a different name from nearly every director [Directors of Meteorological Institutes around the world].” He reasoned, “The question of an International Nomenclature of Clouds becomes of the highest importance.”

Three members of the Clouds Commission of the International Meteorological Committee, aka International Meteorological Organization (now the World Meteorological Organization) joined forces to compile the Atlas: Hugo Hildebrand Hildebrandsson (Swedish; 19 August 1838 – 29 July 1925), a professor at Uppsala university who had prepared a cloud atlas of 16 photographs in 1880; Albert Riggenbach (Swiss; 22 August 1854 – 28 February 1921) – he took the first successful pictures of cirrus clouds; and Léon Teisserenc de Bort (French; 5 November 1855 in Paris, France – 2 January 1913), also notable as co-discoverer of the stratosphere.

The Atlas was adopted in almost all countries. It was reprinted in 1910, without substantial amendments. But the subject of further refinement of cloud classification remained. As a result the International Atlas of Clouds and Study of the Sky, Volume I, General Atlas was published in 1932 by the International Commission for the Study of Clouds. A modified edition of the same work appeared in 1939, under the title International Atlas of Clouds and of Types of Skies, Volume I, General Atlas. As the World Meteological Association notes, “The latter contained 174 plates: 101 cloud photographs taken from the ground and 22 from aeroplanes, and 51 photographs of types of sky. From those photographs. 31 were printed in two colours (grey and blue) to distinguish between the blue of the sky and the shadows of’ the clouds. Each plate was accompanied by explanatory notes and a schematic drawing on the same scale as the photograph, showing the essential characteristics of the type of cloud.”

A new version of the International Cloud Atlas was published in 1956 in two volumes: Volume I contained a descriptive and explanatory text on the whole range of hydrometeors (including clouds), lithometeors, photometeors and electrometeors; Volume II contained a collection of 224 plates (123 in black and white and 101 in colour) of photographs of clouds accompanied by an explanatory text.

The 1956 edition of Volume II had not been reprinted or revised until the preparation of the present edition. A revised version of Volume l, however, was published in 1975 under the title Manual on the Observation of Clouds and Other Meteors. The present Volume II of the International Cloud Atlas (2017) contains 196 pages of photographs, 161 in colour and 35 in black and white – many images contributed by cloud enthusiasts from all over the world.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.