Before he became a great actor Alan Rickman was a post-graduate student in graphic design at London’s Royal College of Art. In 1969 and 1970, Rickman contributed to the RCA’s in-house magazine Ark. He edited copy and wrote an article called Child’s Play about his time working in a London play park.

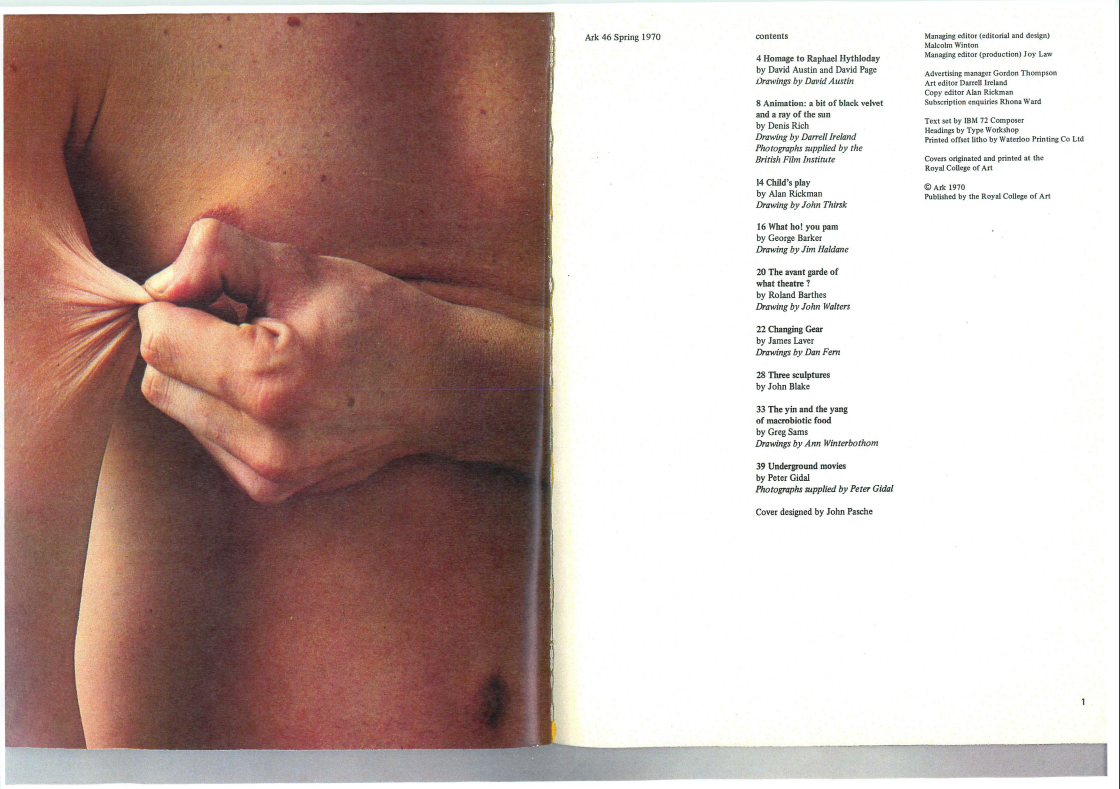

ARK magazine, issue 46 (spring 1970): ‘The New Avant Garde part two.’ Managing Editor (editorial and design): Malcolm Winton; Managing Editor (production): Joy Law; Advertising Manager: Gordon Thompson; Art Editor: Darrell Ireland; Copy Editor: Alan Rickman. Contributors include: David Austin & David Page; Denis Rich & Darrell Ireland; Alan Rickman; John Thirsk; George Barker; Jim Haldane; Roland Barthes; John Walters; James Laver; Dan Fern; John Blake; Greg Sams; Ann Winterbothom; Peter Gidal; John Pasche.

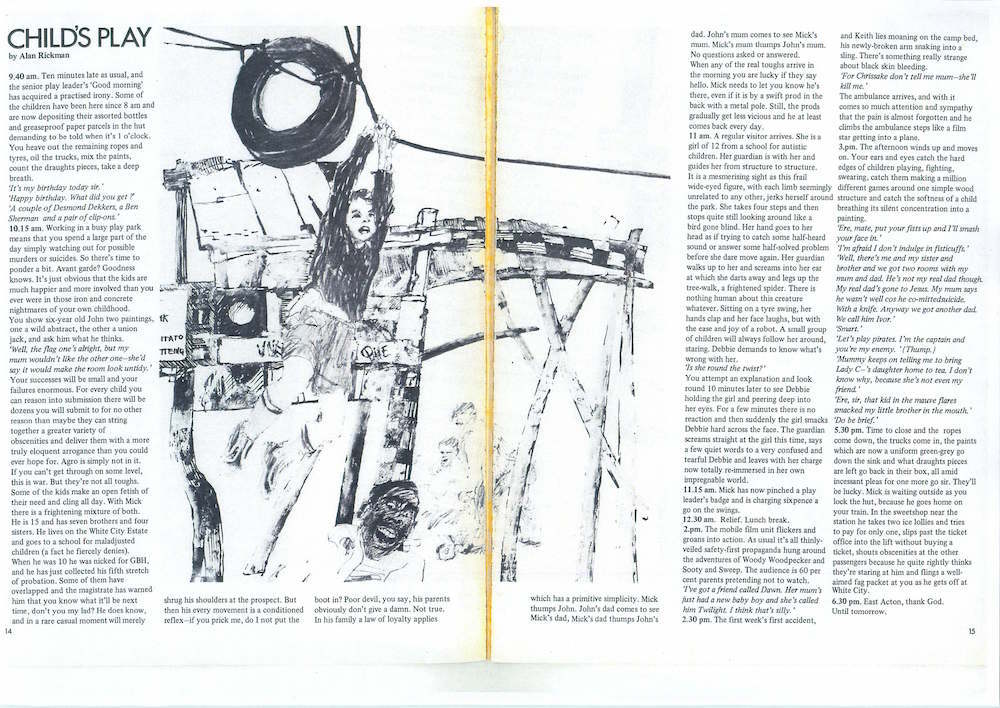

Thanks to the RCA archive, we can now read Alan Rickman’s story from ARK issue 46 (spring 1970). Neil Parkinson tells us the illustration to Rickman’s piece is by John Thirsk, and the cover is by John Pasche (the latter was the designer of the famous Rolling Stones logo). All three were RCA students in Graphic Design at the time.

Alan Rickman’s article is laced with sardony and delivered with an erudite sneer to the feisty and unusual children he helps. It’s impossible not to find traces of the manipulative Valmont he played in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s stage production of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, and, more vitally, his work as the coiling, expressive and seductive Snape in the Harry Potter films. Rickman was empathetic with good and malevolent children. He understood and enjoyed how their outward cruelty and fear belied more complex desires and emotions.

CHILD’S PLAY, by Alan Rickman.

9.40. 10 Minutes late as usual, and the team leader’s ‘Good Morning’ has acquired a practised irony. Some of the children have been here since 8am and are now depositing their assorted bottles and greaseproof paper parcels in the hut demanding to be told when it’s 1 o’ clock. You heave out the remaining ropes and tyres, oil the trucks, mix the paints, count the draughts pieces, take a deep breath.

‘It’s my birthday today sir’

‘Happy birthday. What did you get?’

‘A couple of Desmond Dekkers, a Ben Sherman and a pair of clip-ons’

10.15. Working at a busy play park means that you spend a large part of the day simply watching out for possible murders or suicides. So there’s time to ponder a bit. Avant garde? Goodness knows. It’s just obvious that the kids are much happier and more involved than you ever were in those iron and concrete nightmares of your own childhood. You show six-year-old John two paintings, one a wild abstract, the other a union jack, and ask him what he thinks. ‘Well, the flag one’s alright, but, but my mum wouldn’t like the other one – she’d says it would make the room look untidy.’

Your successes will be small and your failure enormous.

For every child you can reason into submission there will be dozens you will submit to for no other reason than maybe they can string together a great variety of obscenities and deliver them with a more truly eloquent arrogance than you could ever hope for. Agro is simple not in it. If you can’t get through on some level, this is war. But they’re not all toughs. Some of the kids make an open fetish their need and cling all day.

With Mick there is frightening mixture of both. He is 15 and has seven brothers and four sisters. He lives on the White City Estate and goes to school for maladjusted children (a fact he fiercely denies). When he was 10 he as nicked for GBH, and he has just collected his fifth stretch of probation. Some of them have overlapped and the magistrate has warned him that you know what it’ll be next. time, don’t you my lad? He does know and in a rare casual moment will merely shrug his shoulders at the prospect. But then his every movement is a conditioned reflex – if you prick me, do I not put the boot in? Poor devil, you say – his parents obviously don’t give a damn. Not true. In his family a law of loyalty applies which has a primitive simplicity. Mick thumps John. John’s dad comes to see Mick’s dad. Mick’s dad thumps John’s dad. John’s mum comes to see Mick’s mum. Mick’s mum thumps John’s mum. No questions asked or answered.

When any of the real toughs arrive in the morning you are lucky if they say hello. Mick needs to let you know he’s there, even if it is by a swift prod in the back with a metal pole. Still, the prods gradually get less vicious and at least he comes back every day.

11 am. A regular visitor arrives. She is a girl of 12 from a school for autistic children. Her guardian is with her and guides her from structure to structure. It is a mesmerising sight as the frail, wide-eyed figure, with each limb seemingly unrelated to any other, jerks herself around the park. She takes four steps and then stops quite still looking around like a bird gone blind. Her hand goes to her head as if trying to catch some half-heard sound or answer some half-solved problem before she dare move again. Her guardian walks up to her and screams into her ear at which she darts away and legs up the tree-walk, a frightened spider. There is nothing human about this creature whatever. Sitting on a tyre swing, her hands clap and her face laughs, but with the ease and joy of a robot. A small group of children will always follow her around staring. Debbie demands to know what’s wrong with her.

‘Is she round the twist?’

You attempt an explanation and look around 10 minutes later to see Debbie holding the girl and peering deep into her eyes. For a few minutes there is no reaction then suddenly the girl smacks Debbie hard across the face. The guardian screams straight at the girl this time, says a few quiet words to a very confused and tearful Debbie and leaves with her charge now totally re-immersed in her own impregnable world.

11:15am. Mick has now pinched a play leader’s band and is charging sixpence a go on the swings.

12:30am. Relief. Lunch break.

2.pm. The mobile film unit flickers and groans into action. As usual, it’s all thinly-veiled safety-first propaganda hang around the Adventures of Woody Woodpecker and Sooty and Sweep. The audience is 60 per cent parents pretending not to watch.

‘I’ve got friend called Dawn. Her mum’s just had a new baby boy and she’s called him Twilight. I think that’s silly.’

2.30pm. The first week’s first accident, and Keith lies moaning on the camp bed, his newly-broken arm snaking into a sling. There’ something rally strange about black skin bleeding.

‘For Chrissake don’t tell mum – she’ll kill me.’

The ambulance arrives, and with it comes so much attention and sympathy that the pain is almost forgotten and he climbs the ambulance steps like a film star getting into a plane.

3pm. The afternoon winds up and moves on. Your ears and eyes catch the hard edges of children playing, fighting, swearing, catch them making a million different games around one simple wood structure and catch the softness of a child breathing with silent concentration into a painting.

‘Ere, mate, put your fist ip and I’ll smash your face in.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t indulge in fisticuffs.’

‘Well, there’s me and my sister and brother and we’ve got two rooms with my mum and dad. He’s not my real dad though. My real dad’s gone to Jesus. My mum says he weren’t well cos he committed suicide. With a knife. Anyway we got another dad. We call him Ivor.’

‘Smart.’

‘Let’s play pirates. I’m the captain and you’re my enemy.’ (Thump). ‘Mummy keeps telling me to bring Lady C-‘s daughter home to tea. I don’t know why, because she’s not even my friend.’

‘Ere, sir, that kid in the mauve flares smacked my little brother in the mouth.’

‘Do be brief.’

5.30pm. Time to close and the ropes come down, the trucks some in, the paints which are now a uniform green-grey go down the sink and what draughts pieces are left go back in the box, all amid incessant pleas for one more go sir. They’ll be lucky. Mick is waiting outside as you lock the hut, because he goes home on your train. In the sweetshop near the station he takes two ice lollies and tries to pay for only one, slips past the ticket office into the lift without buying a ticket, shouts obscenities at the other passengers because he quite rightly thinks they are staring at him and flings a well aimed fag packet at you as he gets off at White City.

6.30 pm. East Acton, thank god until tomorrow.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.