1. B-Movie.

Let’s begin our story in an office somewhere in the West End of London, where our hero–the aptly named Michael Winner–sits behind his desk smoking one of the twenty Havana cigars he gets through a day. In front of him are a scatter of scripts, letters, writing paper, ink, pens, and an overfull ashtray. On the wall behind: signed photographs, a poster for The Cool Mikado, and a calendar for 1962. Michael is a young and ambitious movie director. He is auditioning a young actor for his next movie.

Opposite sits Oliver Reed. He is “sensitive and quietly spoken,” smokes a cigarette. The room a fug of blue and grey smoke. Though he likes to claim he learned how to act by watching people getting drunk in pubs, Reed is learning his trade working on Hammer horror films. He’s good. Brooding and intense, as the critics have described him–with a stillness and a great quality of danger. His most notable role to date has been as the ill-fated lycanthrope Leon in The Curse of the Werewolf. He has yet to acquire the reputation as a legendary hell-raiser which will cost him the role of James Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service in 1967 and later bring him the notoriety that ultimately damaged his career in the 1980s and 1990s.

Winner likes Reed. He has promise–charisma–the look of a real movie star. Reed is more interested in showing some of his poetry. Now there’s a story for another day of a treasure to be found–the lost odes of Oliver Reed. He tells Winner about a script he has written–a strange tale about a man who carries his home on his back, of “people on a hill living in a wardrobe.” Reed thinks Winner must direct it. Winner thinks otherwise. The script is uncommercial, too “esoteric” but still he would like to cast Reed in his latest picture West 11.

Our hero is on the path to learning a key rule to success: be your own boss.

From his earliest days Winner knew life is an adventure to be gained. The first rule of which is to make your own success. At fourteen he was writing a column Michael Winner’s Showbiz Gossip for a local paper the Kensington Post. At Cambridge University, where he studied law and economics, he was the youngest editor of the student newspaper the Varsity.

Christmas 1954, Winner landed a job as an assistant or “call boy” with the BBC. It was another learning curve.

I was working on an afternoon children’s play. An old actress turned round. ‘Go to my dressing room and get my handbag, would you?’ she said. I looked behind me. ‘Some idiot’s got to get her handbag,’ I thought. But she was talking to me! This didn’t fit my view of myself as Cambridge undergraduate wit, writer and general genius. The trouble with university, and I see little difference today, is that it induces in the students the belief that they’re special. That they are somehow, at Oxford and Cambridge particularly, above other people. Clever. Destined for great things. In fact they are, on the whole, a load of lazy, over-opinionated twits. That’s what I was as I walked along the corridors looking for the old actress’s dressing room to fetch her handbag.

By 1955, he was writing another showbiz column in Showgirl Glamour Revue. He then started working on films with Harold Baim–King of the Quota Quickies.

Baim produced Winner’s early short films and introduced him to others who would help make his first movies. Winner learned his directorial skills making films like the no-budget nudey or rather soft corn movie Some Like It Cool about naturism, and the B-movie thriller Out of the Shadow (aka Murder On The Campus), both in 1961. He worked with Baim again on The Cool Mikado–a disastrous and disappointing comic reworking of the Gilbert & Sullivan opera starring Frankie Howerd and a host of British comedy talent.

18th July 1962: British film director Michael Winner (left) in conversation with producer Harold Baim during the filming of ‘The Cool Mikado’. (Photo by Terry Fincher/Express/Getty Images)

Still The Cool Mikado gave Winner enough leverage to make his next feature West 11–another low budget thriller but this time with a script that offered him a chance to showcase his directing talents.

Winner was teamed with a new producer Danny Angel, who had his own ideas of how to make the movie. When Winner suggested Julie Christie for the female lead. Danny Angel said, ‘Julie Christie’s a B-movie actress. Everybody knows she’ll never get anywhere.’ Winner disagreed. He thought her the best. Angel asked, ‘Who’d want to fuck Julie Christie?’ ‘I would!’ said Winner. ‘Well, you’re homosexual,’ Angel replied.

Then there was Sean Connery.

He’d finished shooting James Bond which everyone thought would be a disaster. I thought he’d be terrific. Danny Angel said, ‘Another B-picture actor! no one will ever be interested in Sean Connery.’

When Winner suggested Oliver Reed, Angel dismissed him as ‘another B-picture actor.’

James Mason made it known he would like to play the seedy army captain. But Angel nixed the offer claiming Mason was ‘a has-been.’

It was apparent Winner was not going to make the film he wanted to make with the actors he wanted. Instead, Danny Angel signed up Alfred Burke, Kathleen Breck and Eric Portman.

Our hero had learnt another key rule of success: to direct the films you want you must also be the producer.

2. Intermission.

During the Second World War Eric Sykes served with the Special Liaison Unit, where he met Flight Lieutenant Bill Fraser. He also made the acquaintance of fellow RAF serviceman Denis Norden, with whom he worked on the production of troop entertainment shows. The friendship with both men would prove crucial to Sykes after the war when he was a jobbing writer on Civvy Street. Fraser became an actor. Norden a highly successful scriptwriter.

Sykes moved to London where he hoped to start his career in show business. He moved into a low rent apartment. It was the coldest winter in memory. By the end of the week, Sykes had no work, no money and hadn’t eaten in days. One night walking the streets to keep warm he met Bill Fraser who was starring at the Playhouse Theatre. Fraser invited Sykes to his show. He gave him food and drink and offered him a job writing gags.

Through Fraser, Sykes was introduced to Frankie Howerd, who was then the biggest star on radio. Howerd asked if he would write routines for him. While Howerd was performing on stage, Sykes wrote his first monologue for the star–“Taking Two Elephants to Crewe”. Howerd liked it and paid him £5. It was enough money to eat and pay two weeks rent. His career as comedy writer had begun.

3. Forthcoming Attractions.

So it came to this. West 11 did okay. The critics were impressed with Winner’s innovative directing. He edited in camera–only shooting what was required. No master shot. He had learned from his time working as an editor with Baim, and often cut his own movies under the name Arnold Crust.

The film’s mild critical success helped Winner produce and direct his next movie The System. He was now free to work with Oliver Reed–a relationship that would span six movies and four decades.

3. Main Feature.

The System was to be the film that changed Michael Winner’s life. This was not at first apparent when the film opened in England. The film dealt with Tinker (Oliver Reed) a seaside photographer who leads “a gang of young men preying on female tourists at a seaside town in search of sexual kicks.” It was filmed on location in and around Torquay during the spring of 1963. According to the actress Julia Foster in Robert Sellers’ biography of Reed What Fresh Lunacy Is This? everyone stayed at the same hotel leading to ‘some mad moments.’

‘There were a lot of drunken parties there. I remember my father came down to visit and one night went into the communal bathroom and found one of the actors drowning in the bath and rescued him.’

Reed was at the epicentre of the drunken mayhem. On one occasion he hung fellow actor David Hemmings upside down out of a second-storey window at the hotel. There was a sixty foot drop with a set of spiked railings below. The incident still irked Hemmings when he described it in his autobiography 40-years later:

‘How do you like this, boy?’ Ollie growled. ‘Wanna come up, boy?’

Hemmings did want to come up and concluded that Reed “for all his charismatic, cavalier efforts as an apprentice hell-raiser, was inclined to bully anyone smaller than himself–like me.”

Much of Reed’s bravado covered-up his own insecurities and self-doubt. Years later, when asked by his brothers, David and Simon, why he had not gone to Hollywood, Reed said:

‘I don’t think I can do it. I don’t really want to do it.’

This admission was paralleled by a scene in the The System when Reed’s character is asked by Jane Merrow’s character why he remains in such a small seaside town. When asked if he likes living there he replies, ‘No, not particularly.’

Merrow asks, ‘Then why stay?’

‘Perhaps I’m a little nervous of going anywhere bigger.’

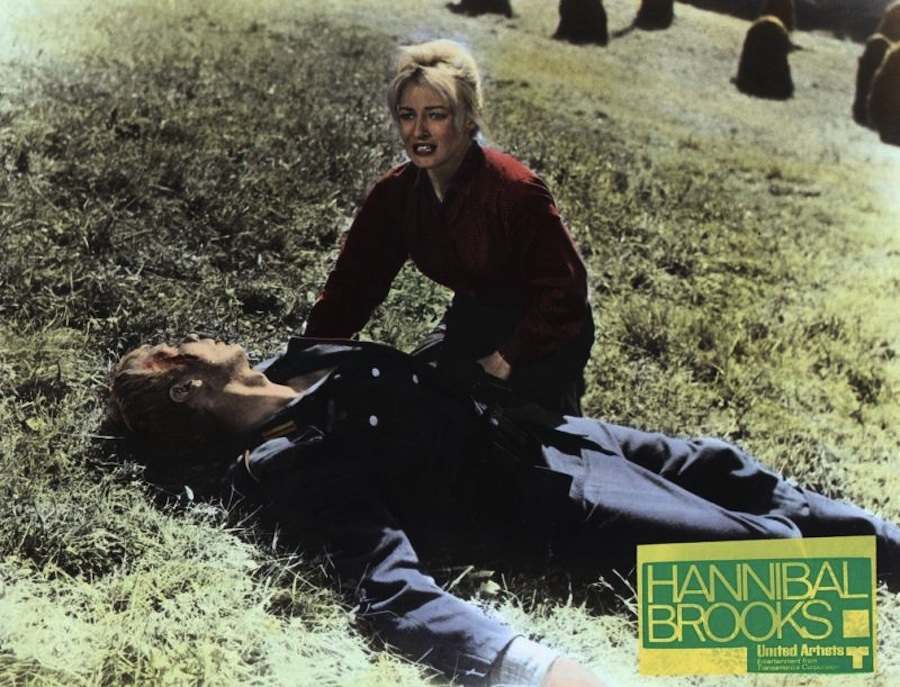

Jane Merrow and Oliver Reed in ‘The System’ (1963).

Going to Hollywood, Reed later admitted, ‘might have made all the difference,’ but it wasn’t in his nature, as he explained to the actress, Georgina Hale:

‘You know, Georgie, I could have gone to Hollywood but I chose life instead.’

Michael Winner avoided Reed’s drunken lunacy during filming.

‘I absolutely loved Oliver. He was the kindest, the quietest, and gentlest man in the world, and the most polite and well behaved, except when he had a drink. But I very seldom saw him drunk on set because he knew I didn’t like that. Once or twice he may have had a bit of a hangover from the night before, but nothing remotely serious; not like today, where half of them are on drugs. But the menace at night, no question. Utterly professional on set–in the evening a disaster.

‘Drunks on the whole are immensely quiet and dignified when sober. But when they’re drunk, they’re drunk. They’re two people; they’re Jekyll and Hyde. I remember once I met Ollie in a restaurant and he went out and challenged someone to a fight, he was always doing that, and he always lost the fight. So he went out into Hyde Park in a beautiful Savile Row suit to fight this bloke and came back having been thrown in the round pond; he was soaking.’

David Hemmings was also wary of Reed.

‘He was never a man you would miss–broad, intelligent, funny, frightening, and deeply unpredictable. He could drink twenty pints of lager with a gin or crème de menthe chaser and still run a mile for a wager.’

Reed’s antics were to cost him. One night at the Crazy Elephant nightclub in London, he was glassed in the face by a young thug. Reed was at a urinal when the man attacked him. Broken glass was “thrust in his face and he dropped like a stone,” as Robert Sellers described it.

As he lay prone on the floor five blokes started laying about him; feebly he lifted his hands for protection against the volley of fists and boots. Managing somehow to get outside into the street, blood spurting from his face, he hailed a cab. ‘St George’s Hospital,’ he said, unnerved that he could feel shards of broken glass in his mouth.

On the journey to hospital, Reed fainted twice. He lost several pints of blood. When he arrived at A&E, the wounds were so bad a nurse fainted. Shards of glass had punctured his cheek and lacerated his tongue. He received 36 stitches. When the police questioned him about the attack, Reed refused to press charges, “That wasn’t going to get me my face back.”

The attack gave Reed a bad boy image and made some producers wary of employing him. Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman had been considering Reed as Connery’s replacement for James Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service–but after his glassing they quickly dropped the idea.

The System was a moderate success in the UK. Winner followed it up with another so-so comedy starring Terry-Thomas and Bernard Cribbins. By 1966, he was out of work–again.

A dead end Sunday in April 1966, Winner was in his office in Piccadilly. He was working his way through the mail that had arrived on Saturday. Among the letters was one from the author John Gardner. In it, Gardner congratulated Winner on the success of his latest feature film. It had received rave reviews from Time and Newsweek. The film Gardner mentioned was called The Girl-Getters. Winner was confused. He had never heard of a film called The Girl-Getters and certainly hadn’t made one with that title. Intrigued he picked up copies of the magazines at the local newsagent.

Gardner was right. The reviews were incredible with Winner and Reed singled out for special praise. The Girl-Getters Winner realised was his two year old film The System. By Monday morning, Winner was the hottest director in England.

Reed had also branched out, developing greater depth as an actor under the directorial guidance of Ken Russell.

Russell cast Reed as Debussy in a BBC drama-documentary on Debussy, after seeing the actor on an edition of Juke Box Jury. Russell was intrigued by Reed’s similarity in looks to the composer. It was another needed break for the young actor who was out of work at the time and driving mini-cabs to pay the bills.

Winner signed-up to make two more films. His first choice for lead was obviously Oliver Reed. In 1966, they made The Jokers, a film about two brothers (Reed and Michael Crawford) stealing the Crown Jewels. This was quickly followed by I’ll Never Forget What’s’isname a satire starring Orson Welles and Reed as a disenchanted advertising executive.

In 1968, Tom Wright a man described as “a house painter” from Glasgow sent Winner a story about his experiences as POW in Munich during the Second World War. The story was partially based on Wright’s own experiences of being requisitioned by the Germans to work at the city’s zoo tending to the elephants. Whether Wright had been inspired by Eric Sykes tale of Frankie Howerd taking two elephants to Crewe isn’t known. However, he had recently graduated from Glasgow University in 1963, and had written a play about Robert Burns called There Was a Man in 1965. He had now turned his own experiences of looking after an elephant called Lucy into an adventure story of a POW escaping with an elephant to Switzerland. Winner liked the story and brought in scriptwriters Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais to produce a screenplay.

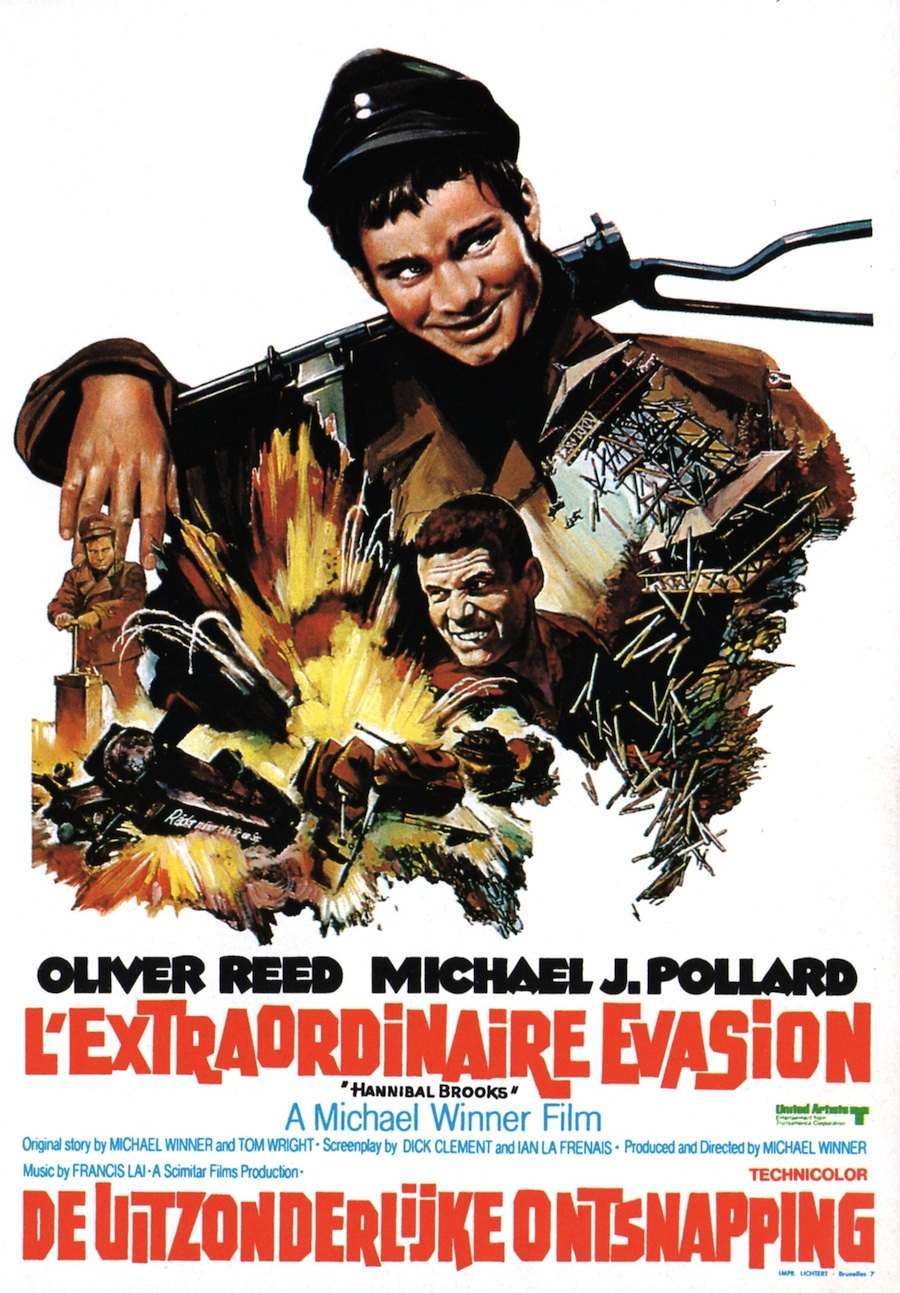

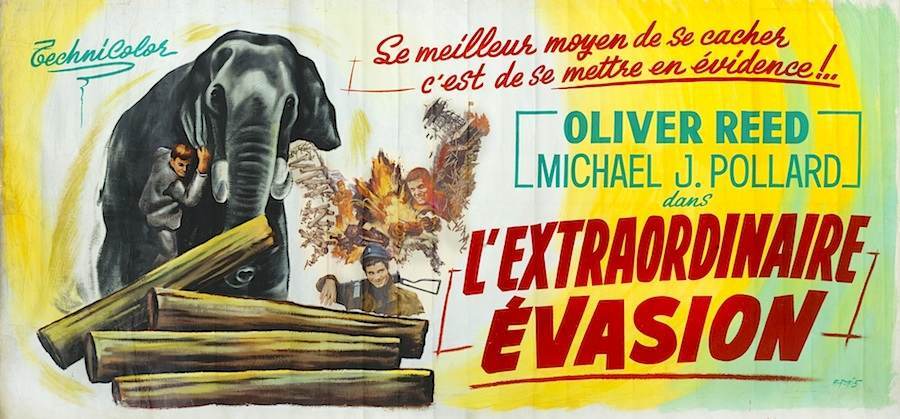

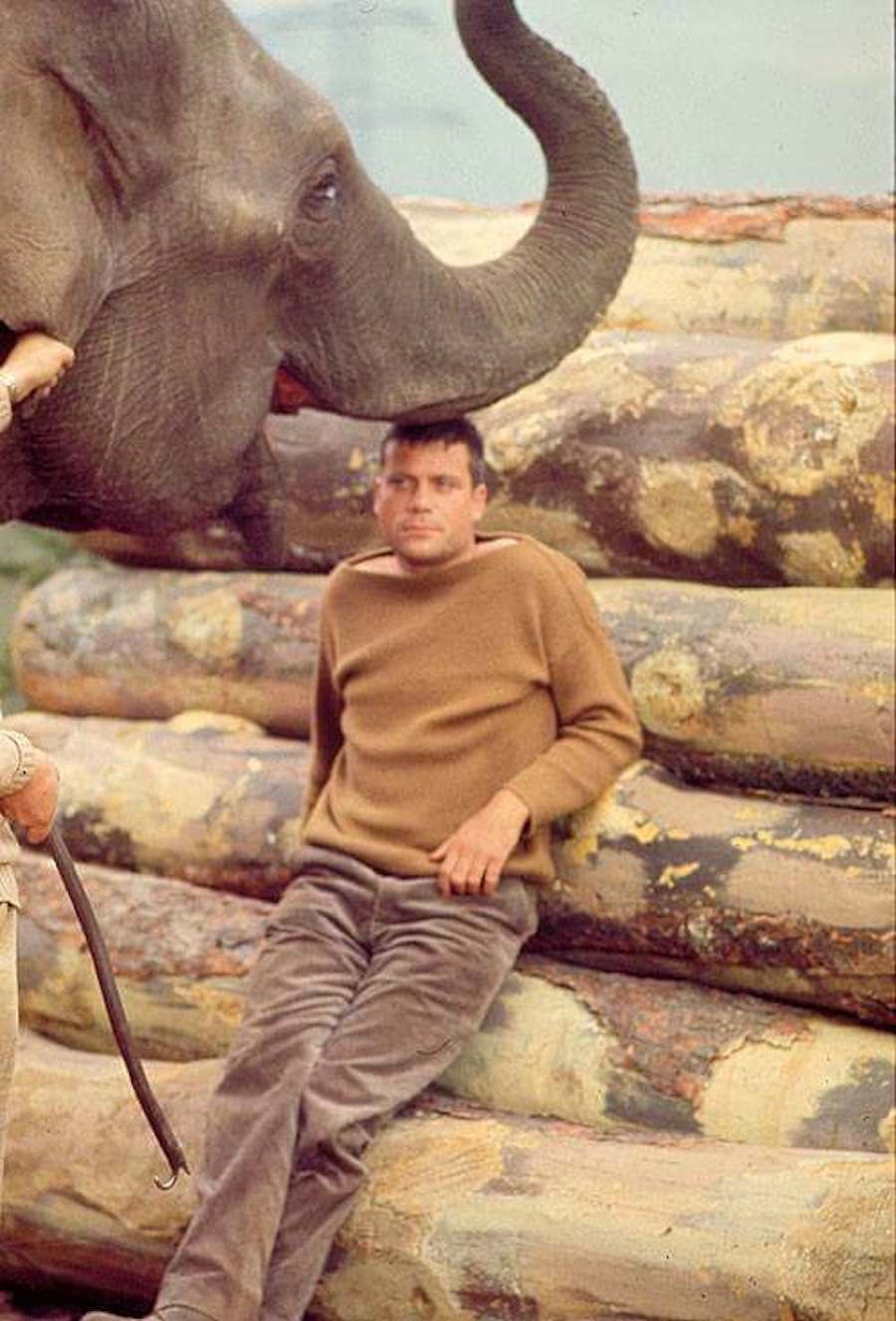

Winner pitched the film to David Pick, Head of Production at United Artists. Pick agreed to make Hannibal Brooks on the one condition it starred Oliver Reed. Winner was more interested in discussing the budget as he wanted 10% contingency in for the elephant. Pick wanted to know why? Winner replied, ‘Because nobody since Hannibal has taken an elephant over the Alps.’

Hannibal Brooks was a big action movie. But Winner had no idea how action films were made, as he later ‘fessed up in his autobiography Winner Take All:

The scenes included a train coming off the rails and crashing down a ravine into a river. German convoys were blown up. People were set on fire. People were shooting to and fro. In one scene the elephant pushed an enormous pile of logs down a hill, killing SS troops advancing up it. They in turn rolled down the mountainside under the logs. A watchtower with troops on it collapsed into a ravine when the elephant pulled a rope attached to one of the struts. I now know it would have been normal to take a Stunt Co-ordinator with a team of at least twenty stunt men. But I didn’t know that then.

For the part of the American guerrilla fighter, Winner cast Michael J. Pollard who had been nominated an Academy Award for his supporting role in Bonnie and Clyde.

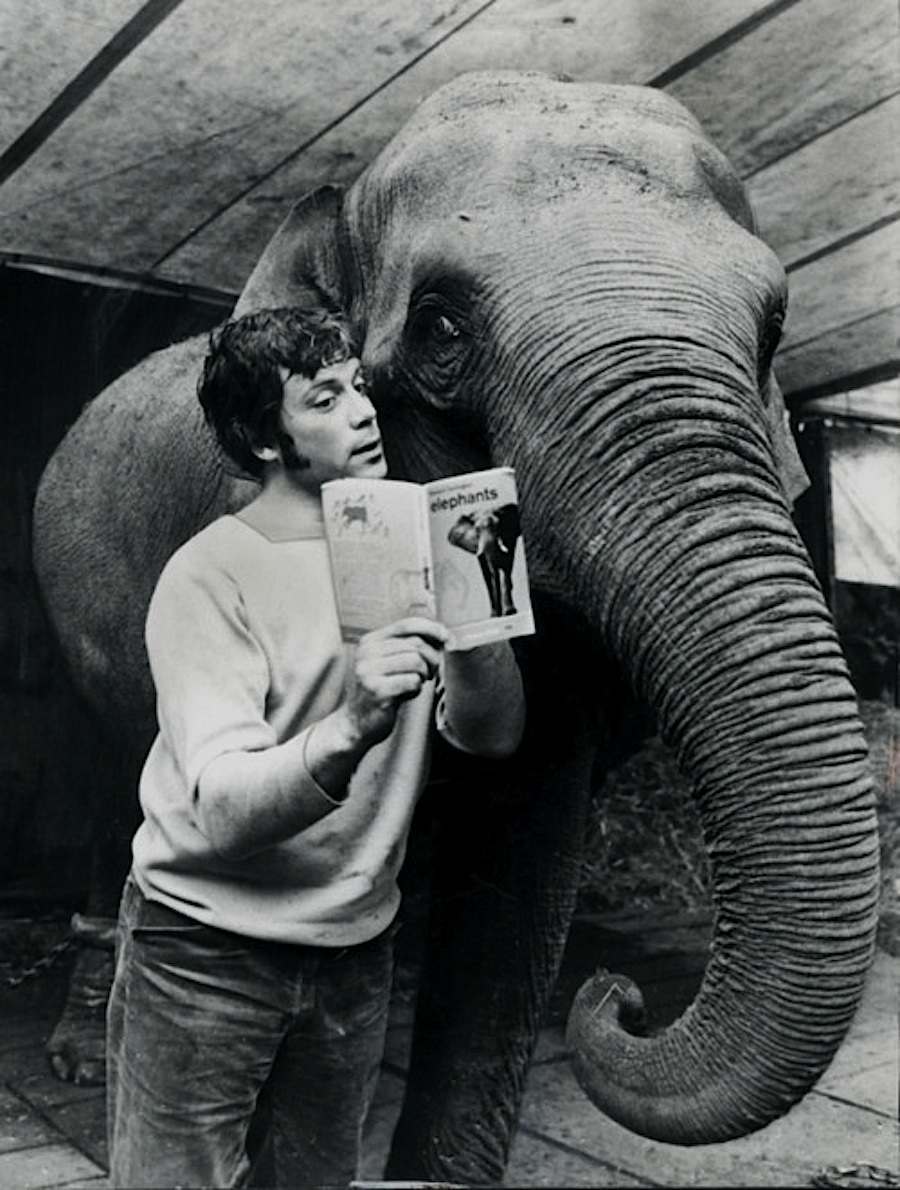

Before they started filming, Reed told Winner that he wanted to stay with the elephant for three nights, as he wanted ‘to get to know the elephant.’ Winner was sceptical.

One thing you learn on movies is: leave the animals to the trainer. The trainer has been with the animal for years. He know how to handle it. The animal cannot have two masters. I said, ‘Oliver, the elephant won’t give a fuck that you’re sleeping with him.’

Oliver slept with it anyway.

Elephants are herd animals and as Winner soon discovered:

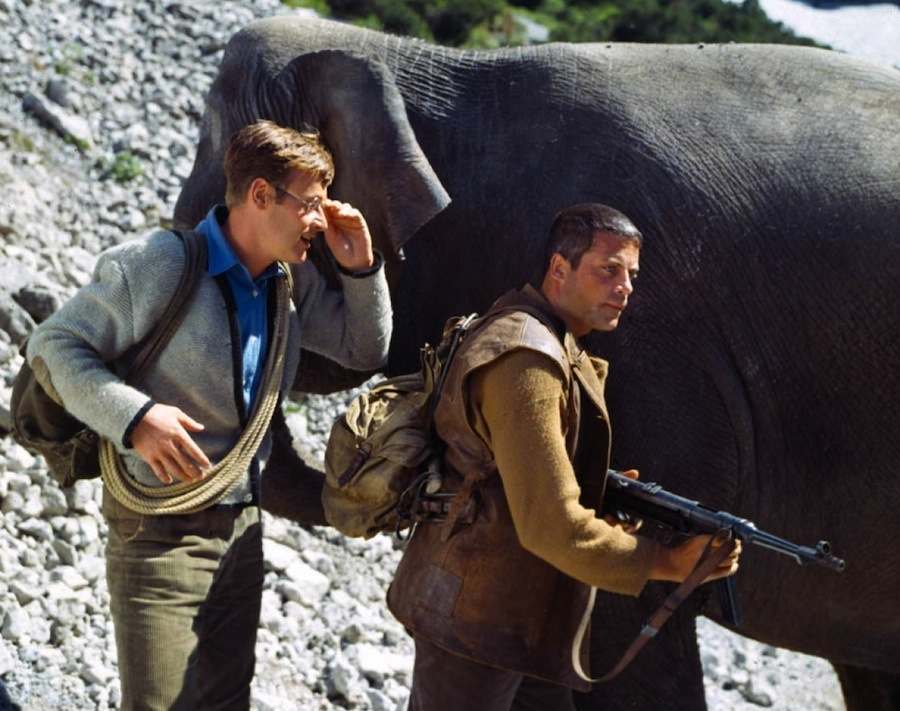

You can’t travel with one, you have to take two. The elephants weigh two and half tons each. We took five tons of elephant plus an enormous amount of feed, plus great tents for them, often along tiny roads with narrow and insecure bridges. The bridges were either two weak to go over or too low to go underneath.

Reed soon discovered that “elephants are not sweet.”

If [Reed and the elephant] were walking along a narrow mountain path with a two thousand-feet drop one side and hard rock face on the other, the elephant would try to squash Oliver against the rock. Or flip him with his heavy tail. We shot in the Munich Zoo. One week after we left, one of the zoo’s elephants we’d had in our movie curled his trunk around a child’s arm as he was holding out a bun, carried it in the air over the moat that protected the public from the elephants, stamped on the child and killed it.

The dangers of the day were countered by Reed’s mayhem during the night.

Oliver at night was absolutely nuts, bless him. Nearly every day we’d have to move his hotel because of he’d pissed on the Austrian flag, or thrown flour over the guests, or run amok through the dining room.

Learning from his experience on The System, Winner made sure his hotel was “at least ten miles from Oliver’s”.

Apart form Reed’s excessive drinking and nocturnal shenanigans, there was Michael J. Pollard and his drugs. Scenes were lost because Pollard was “massively into drugs and pills.”

During the filming of one long sequence–in which a German convoy had crossed over land mines with the SS troops being blown up and running burning from the vehicles–Pollard kept getting his cue wrong.

The guerillas were at the top of the hill shooting down at the Germans. The camera panned slowly along to finish on Pollard who was supposed to wave his arm and say, ‘Come on fellows, let’s go.’ They then all run down the hill towards the camera. Everything worked perfectly, with bullets flying and explosions going off on cue. Until the camera arrived at Pollard who was utterly stoned, waving his arms in the wrong direction shouting, ‘Back up, fellows!’

It took three hours to re-stage the shot. Winner approached Pollard and explained what had gone wrong.

‘Michael, you’re meant to lead them down the hill.’

Pollard looked befuddled. Winner continued.

‘Michael, you know I’m very fond of you and you’re a wonderful actor but you’ve got to straighten yourself out. You have a great future ahead of you. You’ve been nominated for an Academy Award in one of the most important pictures of last year. Why is it you have to keep taking drugs and keep taking pills? There’s no reason for that.’

Pollard looked directly at Winner and said, ‘You don’t share a hotel with Oliver Reed.’

‘Michael, you just won the argument.’

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.