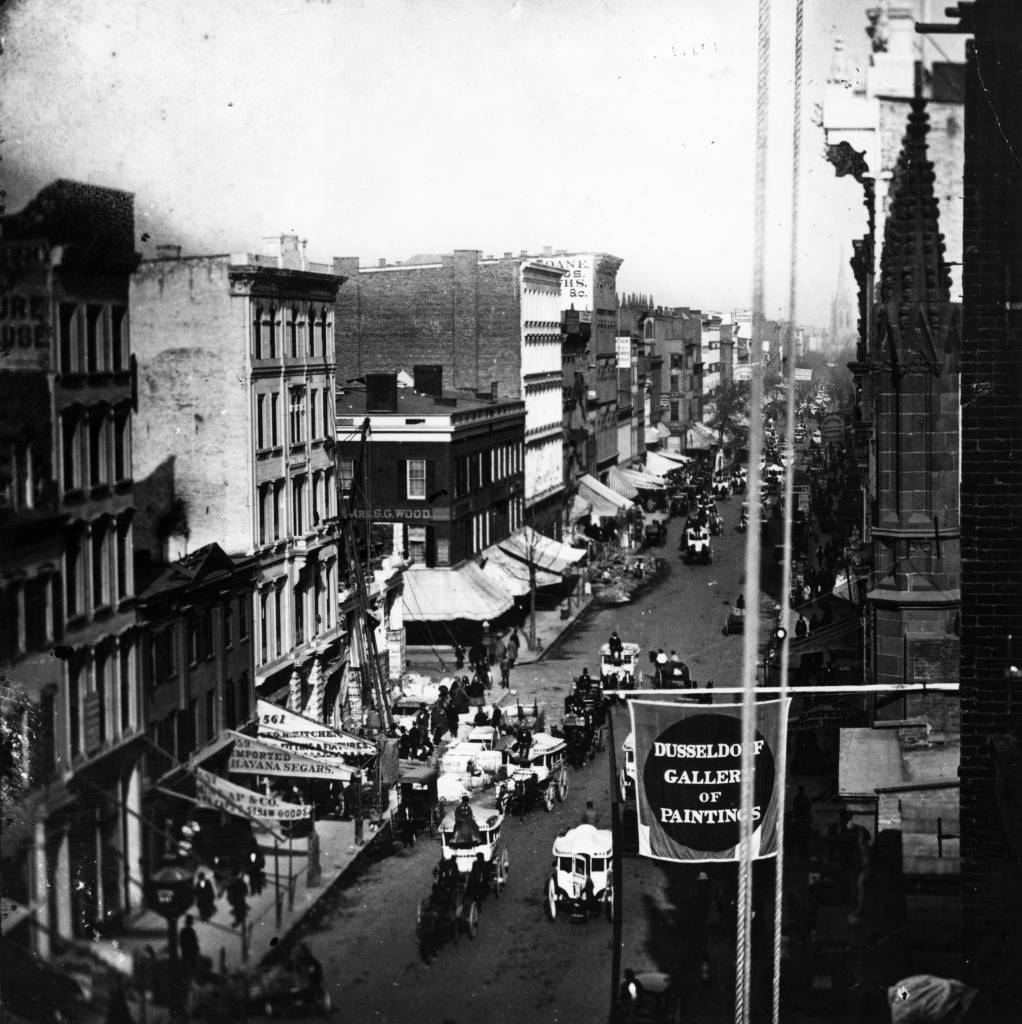

Pfaff’s was America’s first gay bar. Located at 647 Broadway, patrons of the vaulted underground cellar housed in a five-story building included free-thinkers, rebels, cultural outliers and the American poet Walt Whitman, who would tell his biographer: “Pfaff’s ‘Bohemia’ was never reported, and more the sorrow.”

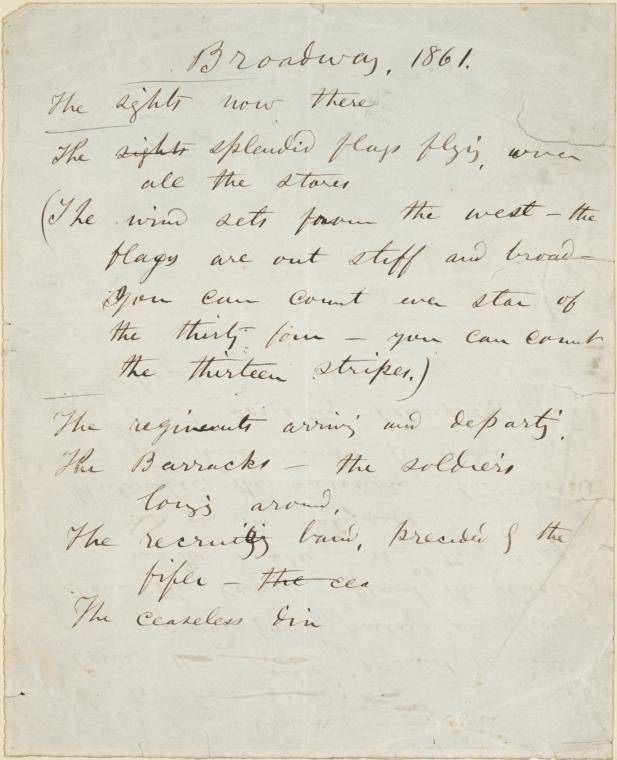

Whitman hailed the bar in his 1861 poem The Two Vaults:

The vault at Pfaffs where the drinkers and laughers meet to eat and drink and carouse

While on the walk immediately overhead pass the myriad feet of Broadway

As the dead in their graves are underfoot hidden

And the living pass over them, recking not of them,

Laugh on laughers!

Drink on drinkers!

Bandy the jest!

Toss the theme from one to another!

Beam up—Brighten up, bright eyes of beautiful young men!

Whitman became a regular at Pfaff’s after getting fired from the Brooklyn Daily Times in 1859.

Under the low-hanging ceiling of Charles Pfaff’s Manhattan beer cellar, Whitman drew inspiration from what one contemporary called “the trysting-place of the most careless, witty, and jovial spirits of New York,—journalists, artists, and poets.”

Edward Whitley, of Lehigh University’s The Vault at Pfaff’s:

From about the mid-1850s to just after the end of the Civil War (give or take a few years), Charles Pfaff’s in midtown Manhattan was a gathering place for a group of New York City writers and artists who attempted to recreate the bohemian lifestyle of Paris’s Latin Quarter that Henri Murger had chronicled in his 1851 book Scènes de la Vie de Bohême.

1859: Traffic on lower Broadway in New York City. (Photo by William England/London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images)

The leader of this group, often referred to as “the King of Bohemia,” was Henry Clapp, Jr., a former antislavery and temperance activist from New England who, upon returning to the United States from a trip to France in 1850, renounced his allegiance to social reform movements of any kind and set up a Parisian-style salon that included intellectuals, utopianists, artists, poets, playwrights, novelists, and actors, along with the occasional banker, politician, and even police officer. In addition to reigning over the kingdom of Bohemia, Clapp was also the founder and editor of The New York Saturday Press, a literary weekly that served as the organ of the Pfaff’s crowd. One of many articles celebrating the bohemian lifestyle that Clapp ran in The Saturday Press described Pfaff’s as “the trysting-place of the most careless, witty, and jovial spirits of New York,—journalists, artists, and poets.

This image by Frank Bellew is from the February 6, 1864 issue of The New York Illustrated News. It claims to depict the writers and artists at Pfaff’s “As they were said to be by a knight of The Round Table,” a reference to recent criticisms of the New York bohemians in The Round Table by Franklin Ottarson

Other notables (now largely forgotten) who drank at the bar, included: painter Elihu Vedder, actresses Ada Clare and Adah Isaacs Menken, and writers George Arnold, Marie Stevens, Bayard Taylor, Fitz Hugh Ludlow and John Brougham.

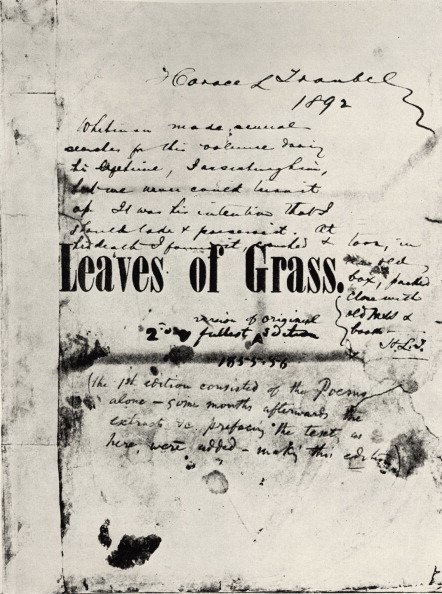

But not all of the denizens of Pfaff’s were “careless, witty, and jovial.” Scholars and biographers have noted for many years that Whitman came to Pfaff’s at a low point in his life. After both the 1855 and 1856 editions of Leaves of Grass failed to catapult its author to literary stardom, Pfaff’s was a place where Whitman could retreat from the public eye and lick his wounds. Clapp’s relationship with Whitman has long been regarded as an important chapter in the publishing history of Leaves of Grass, with Clapp’s advocacy for Whitman in the pages of The Saturday Press contributing significantly to the success of the third edition of Leaves of Grass in 1860. Scholars have recognized for years that Clapp and The Saturday Press (if not the Pfaff’s scene in general) got Whitman back on his feet and put Leaves of Grasson the map.

“You will have to know something about Henry Clapp if you want to know all about me,” Whitman stated years later.

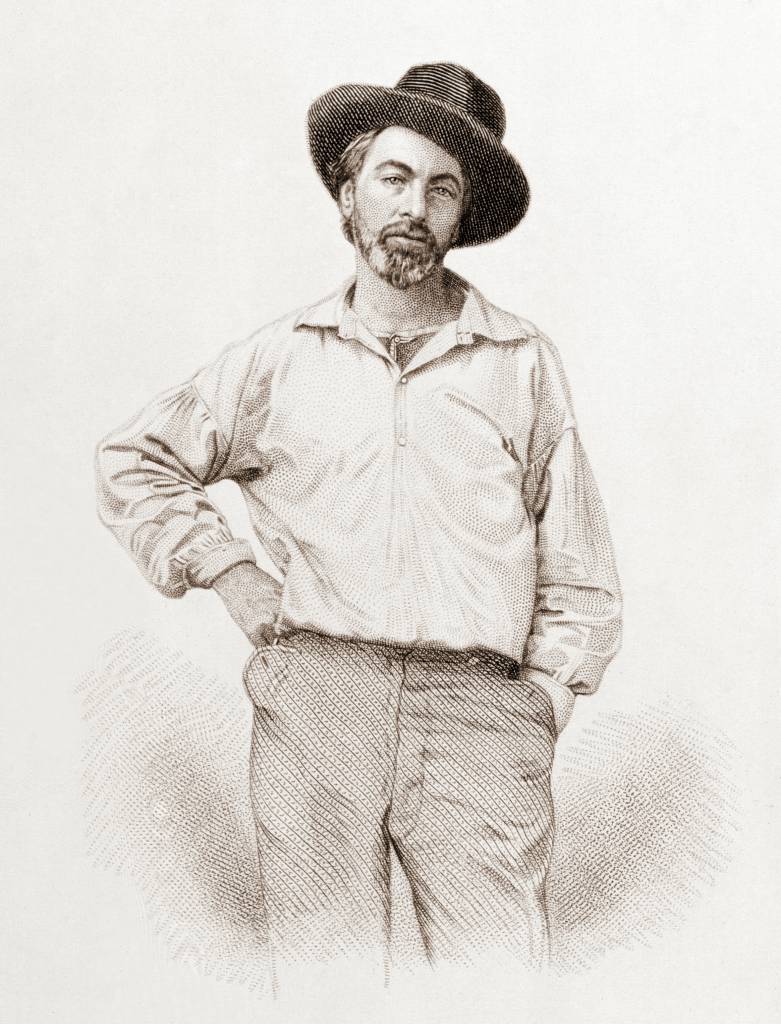

Walt Whitman (1819-1892), age 37, frontispiece to Leaves of grass, Fulton St., Brooklyn, N.Y., 1855, steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison.

Velsor Brush explains how Whitman wound up among the Pfaff’s clientele:

Born on Long Island and raised in Brooklyn, Walt Whitman spent his childhood and early adulthood amid the sights and sounds of New York City and its environs. As a young man Whitman worked as a journeyman printer for several New York newspapers, before ultimately becoming a journalist and editor in his own right. Before committing himself to poetry, Whitman also worked intermittently as a schoolteacher, a carpenter, and a writer of sensational prose fiction. In 1855, Whitman self-published Leaves of Grass, the book of poems that defined his career as a poet; he hoped that Leaves of Grass would take the literary world by storm. While there was a flurry of attention that surrounded the initial publication of his book–including positive appraisals by such luminaries as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Charles Eliot Norton – Whitman did not achieve the immediate fame that he had hoped for. When he released a second and expanded edition of Leaves of Grass the following year that similarly did not catapult him to immediate literary stardom, he withdrew from the public eye for a number of years before releasing the third edition of Leaves of Grass in 1860.

Walt Whitman’s copy of the first edition of his book ‘Leaves of Grass’, with handwritten notes by Horace L. Traubel (later to become one of Whitman’s literary executors).

It is during this period of Whitman’s life that he began frequenting Pfaff’s bar and fraternizing with bohemians such as Henry Clapp, George Arnold, and Ada Clare. If the literary mainstream failed to recognize Whitman’s genius, the Pfaff’s bohemians made up for that lack tenfold. In the pages of the Saturday Press Whitman was lionized as “The New Nebuchadnezzar” of American poetry (May 26, 1860) and made the focus of more media attention than any other writer mentioned in the Press…

Walt Whitman: Leaves of Grass.” New-York Saturday Press. 19 May 1860: 2. Clapp is a probably author of this review given his role as editor of the Saturday Press and his commitment to promoting Whitman’s poetry.

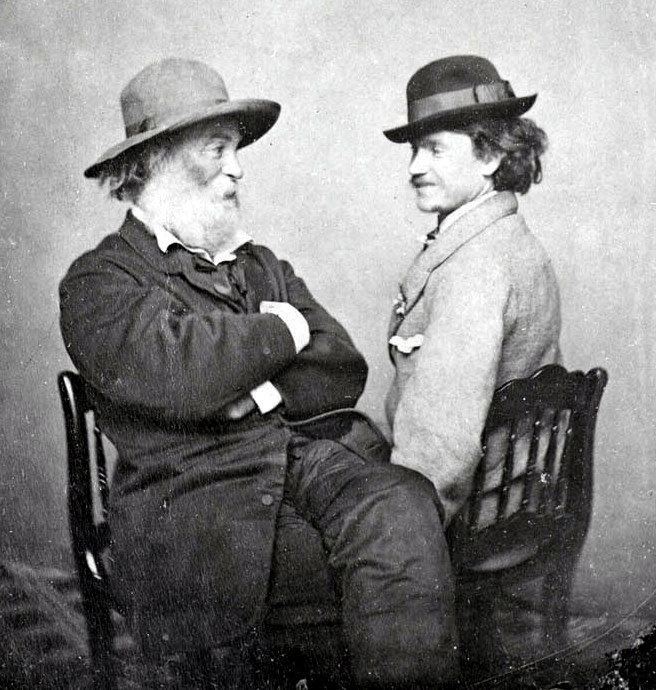

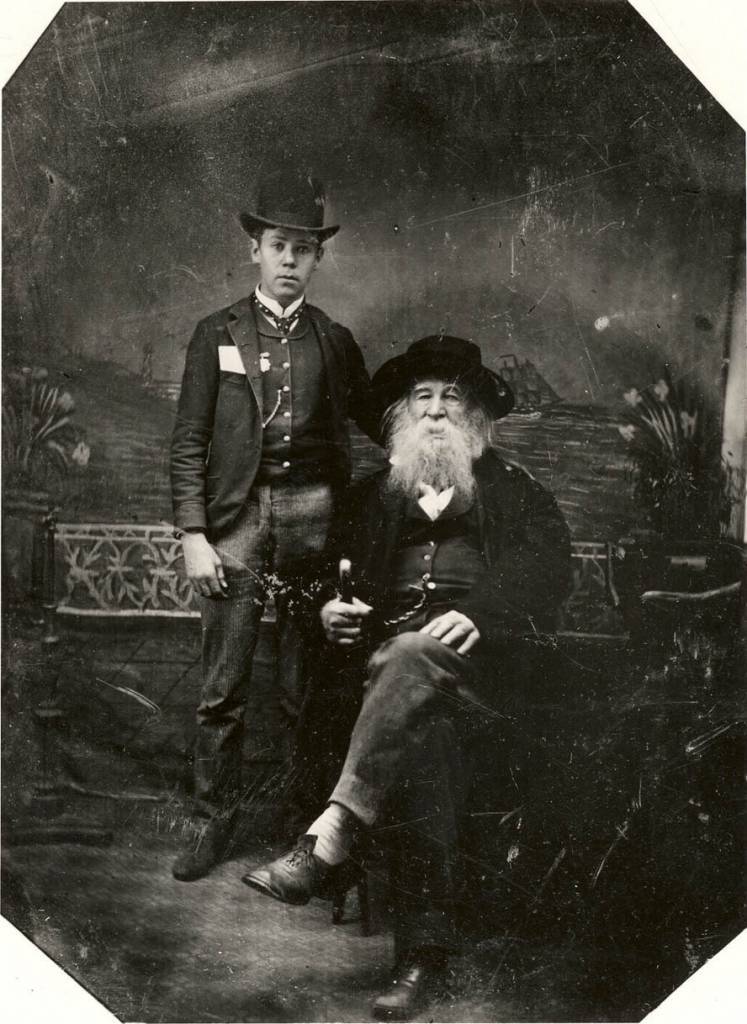

Whitman, like several other bohemians, experimented with the boundaries of human sexuality while at Pfaff’s. As Ed Folsom and Ken Price write in their biography of Whitman, “It was at Pfaff’s, too, that Whitman joined the ‘Fred Gray Association,’ a loose confederation of young men who seemed anxious to explore new possibilities of male-male affection”

Whitman left New York and Pfaff’s in 1862 to work in the hospitals of the Union Army in Washington, D.C., during the U.S. Civil War. He lived in Washington in the years following the War and eventually settled across the river from Philadelphia in Camden, New Jersey, where he spent his twilight years receiving visits from fans and admirers of his poetry. On an August day in 1881, however, Whitman returned to Pfaff’s – now relocated uptown on twenty-fourth street – to visit with Charles Pfaff and reminisce about the bohemian days. When Whitman arrived at Pfaff’s he said that the proprietor “quickly appear’d on the scene to welcome me and bring up the news, and, first opening a big fat bottle of the best wine in the cellar, talk about ante-bellum times, ’59 and ’60, and the jovial suppers at his then Broadway place, near Bleecker Street” (Specimen Days and Collect 188).

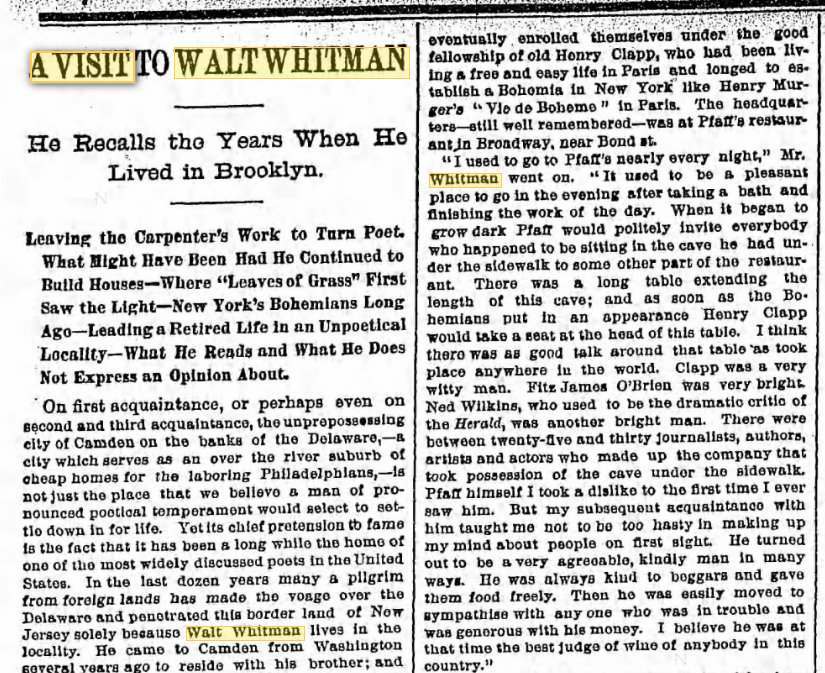

In “A Visit to Walt Whitman” (Brooklyn Eagle. 11 Jul. 1886), Whitman enthused:

“I used to go to Pfaff’s nearly every night. It used to be a pleasant place to go in the evening after taking a bath and finishing the work of the day. When it began to grow dark Pfaff would politely invite everybody who happened to be sitting in the cave he had under the sidewalk to some other part of the restaurant. There was a long table extending the length of this cave; and as soon as the Bohemians put in an appearance Henry Clapp would take a seat at the head of this table. I think there was as good talk around that table as took place anywhere in the world. Clapp was a very witty man. Fitz James O’Brien was very bright. Ned Wilkins, who used to be the dramatic critic of the Herald, was another bright man. There were between twenty-five and thirty journalists, authors, artists and actors how made up the company that took possession of the cave under the sidewalk. Pfaff himself I took a dislike to the first time I ever saw him. But my subsequent acquaintance with him taught me not to be too hasty in making up my mind about people on first sight. He turned out to be a very agreeable, kindly man in many ways. He was always kind to beggars and gave them food freely. Then he was easily moved to sympathize with any one who was in trouble and was generous with his money. I believe he was at that time the best judge of wine of anybody in this country.”

The Vault looks at how Pfaff’s bohemians shaped American culture:

The bohemians of antebellum New York published regularly in the daily newspapers, literary weeklies, and monthly magazines that proliferated throughout the United States in the years leading up to the Civil War. Writers and artists at the beginnings of their careers published in periodicals as a way to build their reputations and attract the attention of book publishers. A number of the periodicals that began during this period, such as The New York Tribune and Harper’s Monthly, became very successful and continued to be published well into the twentieth century. Many other periodicals, however, lasted only for a few years. Two such periodicals, The New York Saturday Press and Vanity Fair, began around the tables at Pfaff’s bar. The Saturday Press ran from October 1858 until December 1860, and was briefly revived in August 1865 only to cease publication again in June 1866. Similarly, Vanity Fair began publishing in December 1859 and ended its run in July 1863.

And the homosexuality? Poetry Bay has more on the bohemian’s sex lives:

And in fact it was at Pfaff’s that Whitman joined the “Fred Gray Association,” a loose confederation of young men who seemed anxious to explore new possibilities of male-male affection. The name was from one of the members, a young man named Fred Gray, the son of a doctor, who went on to become a doctor himself in the Civil War. Among those in the association were Gray, Hugo Fritsch, who was the son of the Austrian consul, and Nat Bloom, who became a successful merchant, and eventually had a store on Broadway.

In Rebel Souls: Walt Whitman and America’s First Bohemians, Justin Martin narrates the story of Pfaff’s creative legacy.

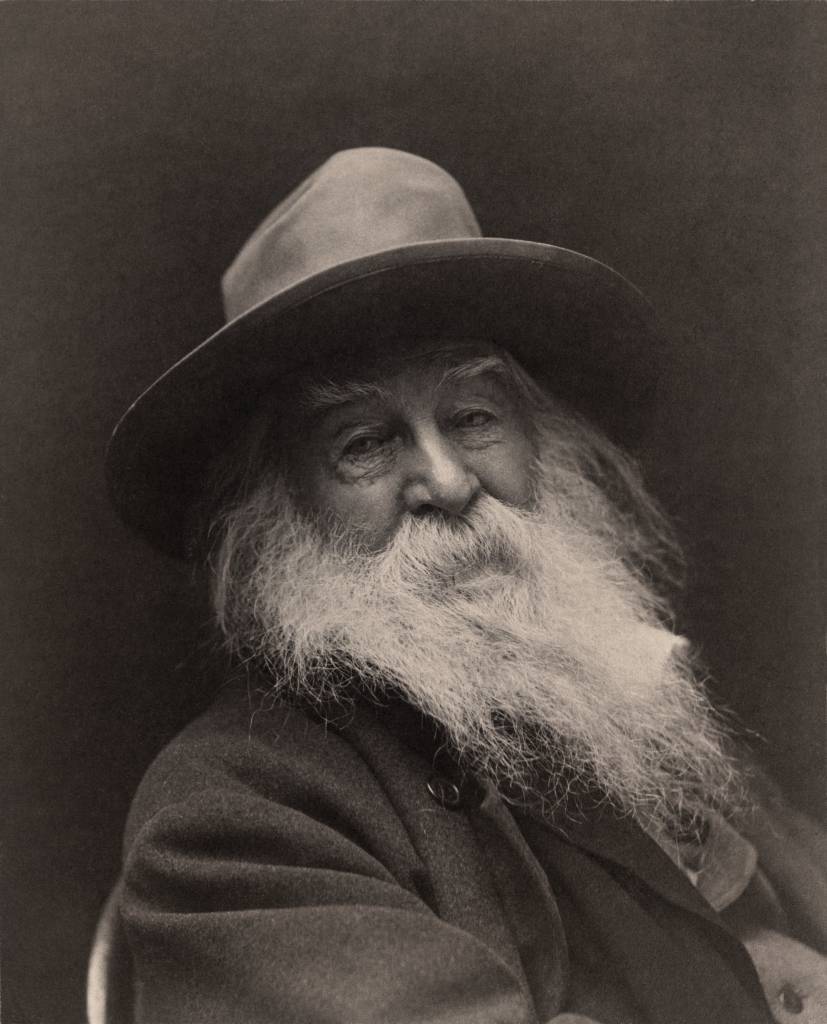

When he started frequenting the saloon, Whitman was thirty-nine years old. He stood roughly six feet, tall for the era, but weighed less than two hundred pounds. He wasn’t yet the beefy, shaggy poet of legend. His hair was cut short, a salt-and-pepper mix of brown and gray. His beard was trimmed. Only later would he put on weight, the wages of stress and illness and advancing age. Only later would he grow his hair long and let his beard go thick and bushy.

But he was already an eccentric dresser. Whitman favored workingmen’s garb, such as his wideawake, a type of broad-brimmed felt sombrero. He liked to wear it well back on his head, tilted at a rakish angle. His trousers were always tucked into cowhide boots. He wore rough-hewn shirts of unbleached linen, open at the collar, revealing a shock of chest hair. Whitman had a rosy complexion, almost baby-like, and quite incongruous for a big man. Because he was meticulous about hygiene, he always smelled of soap and cologne. His manner of dress often struck people as more like a costume. Or maybe it was a kind of armor, protecting the vulnerable man underneath.

Whitman was honored on a ‘Famous Americans Series’ Postal issue, in 1940.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing; Photo imaging by Gwillhickers – U.S. Gov.; Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Maria Popova writes:

… rather than calling it a “semi-gay bar,” Martin proposes “semi-adhesive” — “adhesiveness” being a term from phrenology, that popular 19th-century pseudoscience that enchanted Whitman at least as much as it did George Eliot. Symbolized by two women embracing, “adhesiveness” — as opposed to “amativeness,” romantic love between a man and a woman — connotes, as Martin explains, a “capacity for intense and meaningful same-sex relationships.”

…

When Whitman first began visiting Pfaff’s, Martin writes, he was in an “adhesive,” serious relationship with a young man named Fred Vaughan, nearly two decades the poet’s junior. The two lived together on Classon Avenue in Brooklyn and would often sit at the same table in Pfaff’s larger room. Vaughan was among the first people Whitman showed his coveted, now-famous letter of encouragement from Emerson.

Their romance, however, met its end shortly after the two started frequenting Pfaff’s. Martin notes:

Vaughan had reached an age when he was expected to find a proper mate, that is, a woman.

Vaughan ended up getting married and settled into a rather conventional life. He worked a series of jobs such as insurance salesman and elevator operator and with his wife raised four sons. He also became a terrible alcoholic. In the early 1870s, after roughly a decade of silence, Vaughan reconnected with Whitman, writing him several letters, one of which includes the following heart-rending passage: “I never stole, robbed, cheated, nor defrauded any person out of anything, and yet I feel that I have not been honest to myself — my family nor my friends.” In the letters, Vaughan never spells out the source of his anguish. Perhaps it was the result of living in a state that felt unnatural to him. One letter includes, “My love my Walt is with you always.”

Nothing lasts forever.

!["[Acute gastritis, which carried off Charles Pfaff last week]." Brooklyn Eagle. 27 Apr. 1890: 10. Electronic Source Available Type: newspaper . Genre: obituary, journalism . Abstract: This obituary of Charles Pfaff takes a moment to reflect on the Pfaff's scene and its various participants. Full Text Acute gastritis, which carried off Charles Pfaff last week, removed the proprietor of a "wine cellar" whose supply of the "rosy" kindled more genius than ever met in a New York wine cellar before or since. Such bright spirits as Artemus Ward, Miles O'Reilly, Mortimer Thompson, Fitz James O'Brien, William J. Rose, Walt Whitman, T. B. Aldrich, Fitzhugh [sic] Ludlow, Nat Urner, Charles Dawson Shanly and George Arnold met there and matched the flavor of their wits against the flavor of "Papa" Pfaff's wines. The majority of them died long ago, and those who survive have lost the relish and eager ambition that belonged to them when Pfaff's was at its prime. They are only philosophers now. Then they were poets, wits and true disciples of Bacchus.](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Untitled-17.jpg)

“[Acute gastritis, which carried off Charles Pfaff last week].” Brooklyn Eagle. 27 Apr. 1890: 10.

Full Text:

Acute gastritis, which carried off Charles Pfaff last week, removed the proprietor of a “wine cellar” whose supply of the “rosy” kindled more genius than ever met in a New York wine cellar before or since. Such bright spirits as Artemus Ward, Miles O’Reilly, Mortimer Thompson, Fitz James O’Brien, William J. Rose, Walt Whitman, T. B. Aldrich, Fitzhugh [sic] Ludlow, Nat Urner, Charles Dawson Shanly and George Arnold met there and matched the flavor of their wits against the flavor of “Papa” Pfaff’s wines. The majority of them died long ago, and those who survive have lost the relish and eager ambition that belonged to them when Pfaff’s was at its prime. They are only philosophers now. Then they were poets, wits and true disciples of Bacchus.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.