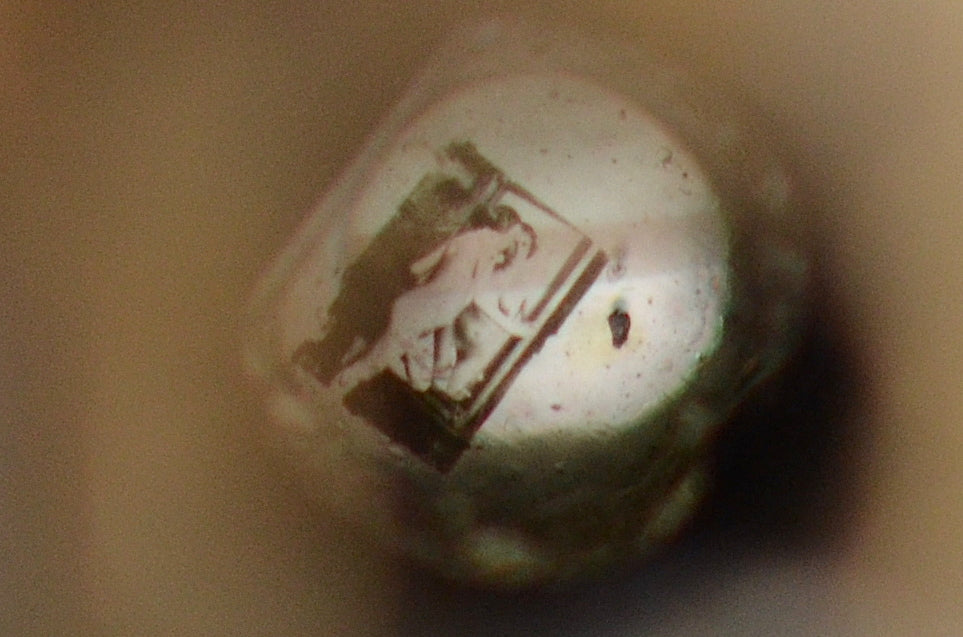

This is story about how when you peer inside the butthole of a small early 20th Century gold-painted charm shaped like a pig, you can see pictures of naked women and people having sex.

In the mid-19th Century, not long after the invention of photography, John Benjamin Dancer (1812 – 1887) began printing tiny photographs onto glass slides at his studio in Liverpool, England. In Paris, René Dagron (1817 – 1900) wondered how to circumvent the need for an expensive microscope to view them. In 1859, Dagron patented the first Stanhope lens mounted with a mini-photograph.

He named it after the magnifying device invented 50 years earlier by Charles, Third Earl Stanhope (1753-1816). In the late-18th century, Stanhope invented lenses which allowed all sorts of “viewers” to house images in secret. Stanhopes, also called Bijoux Photomicroscopiques, became known as ‘peep holes’, ‘peep-eye views’ or ‘peeps’.

A Victorian Alabaster “Stanhope” Optical Viewer or “Peep Egg”

With a view of “The Crystal Palace” – English Circa 1855 Via

The Stanhope is a small glass cylinder with one end ground into a convex form, and a tiny, translucent photograph mounted onto the opposite end. Hold the Stanhope to the light and the microphotograph becomes visible to the naked eye, through its curved lens.

Sir David Brewster (1781-1868) described the Stanhope in On the Photomicroscope for The Photographic Journal, January 15, 1864:

Under the name of bijoux photomicroscopiques, M. Dagron, of Paris, sent to the Exhibition of 1861 a series of these beautiful little optical instruments, which consisted of a plano-convex lens of such a thickness that its anterior focus coincided with the plane side of the lens. By placing the eye behind the convex side, these photographs, invisible almost to the eye, were seen so distinctly and so highly magnified that they excited general admiration.

M. Dagron had presented some of them to the Queen, who admired them greatly; and as he was the only exhibitor, he naturally expected that the ingenuity with which he had produced a new article of manufacture would have received a higher reward than ‘Honorable Mention.’ . . .

In 1860 M. Dagron had taken out a patent in France for this combination of an elongated or cylinder lens with a photograph, under the name of Bijoux Photomicroscopiques. He placed the lens in brooches and other female ornaments; and the combination became so popular, and the sale so great, that fifteen opticians in Paris invaded the patent, and succeeded in reducing

Enterprising types could then insert the miniature lens into things like watch keys, pocket knives, charms, rings, pipes, pens, necklaces, needle cases, letter openers, thimbles and, well, pretty much anything.

In the early 20th Century, Stanhope watch fobs appeared in the shape of pigs. Look through the rear end of one and you could see a picture of Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908), the 22nd and 24th US President.

The photographs embedded in these Stanhope devices made them popular with travellers, who would buy souvenir charms and peep at the tiny pics inside to remember their holidays. Other images included advertisements, Queen Victoria, the Lord’s Prayer and nudes.

Andrew Moisey, a photographic artist and Assistant Professor of the History of Art at Cornell University, notes: “Dagron, it seems, started printing filthy pictures immediately, no doubt in response to a French crackdown on erotic imagery beginning in 1854-5. Erotic Stanhopes were popular throughout the industrialized West into the early twentieth century, but their size has largely hidden them from the history of photography.”

At The Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, a collection of Stanhope erotica 1959 began as contraband that the US Postal Service seized in 1924. “The Institute, which was established in 1947 to research human sexual behavior, did not record who gave up this smut, but the box was labeled, ridiculously, ‘from France’,” says Moisey.

Most Stanhope objects don’t declare themselves to be Stanhopes, the idea being to keep the imagery secret. As Moisy notes:

Sharing, I’d argue, is tiny porn’s climax. In the 1970s in the United States, pornographic theaters allowed people to publicly share in the experience. But you didn’t own the movie; it wasn’t part of you. Not so with spicy Stanhopes. When you put it in your charm on your person in public, it was part of your identity. It would have been a fast way to make a new friend, if the venue was right. For straight men at least, this was homosociality at its most explicit. But the discrete nature of this media gave any kind of sexuality the chance to carefully locate its secret public, and that, I believe, would have been the best thing tiny porn was for.

Stanhope novelties began to lose their popularity as souvenirs. The last true Stanhopes were made in 1972 by Roger Reymond.

Via: Dr Chelsea Nichols, St. Eloi Vintage.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.