Before we get to Hugo Steiner-Prag’s illustrations for Gustav Meyrink’s bestselling novel Der Golem, it might be useful to know what The Golem is.

In Hebrew, Golem means “speechless man”. In Jewish mysticism and Kabbalah, a Golem is a creature in human form made of clay. Animated by saying one of the esoteric names of God, the name is then written down and pushed into the effigy’s mouth or head.

The Golem rises to protect Jews in times of crisis, which, given the incredible persistence of their enemies, have been many.

In the Talmud (Tractate Sanhedrin 38b), Adam was created as a golem (גולם) when his dust was “kneaded into a shapeless husk”. Like Adam, all Golems are created from mud by those close to divinity, but no Golem is fully human.

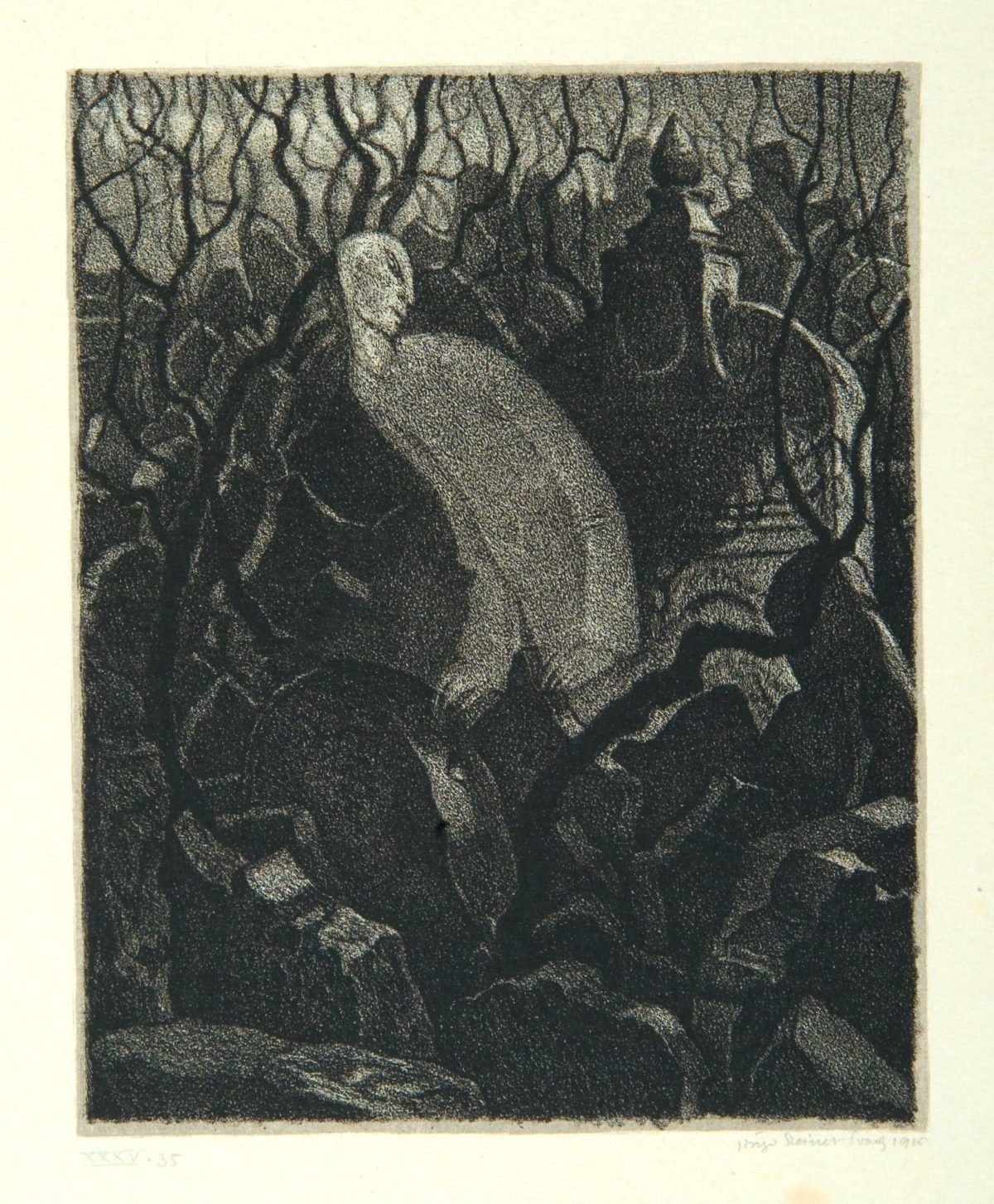

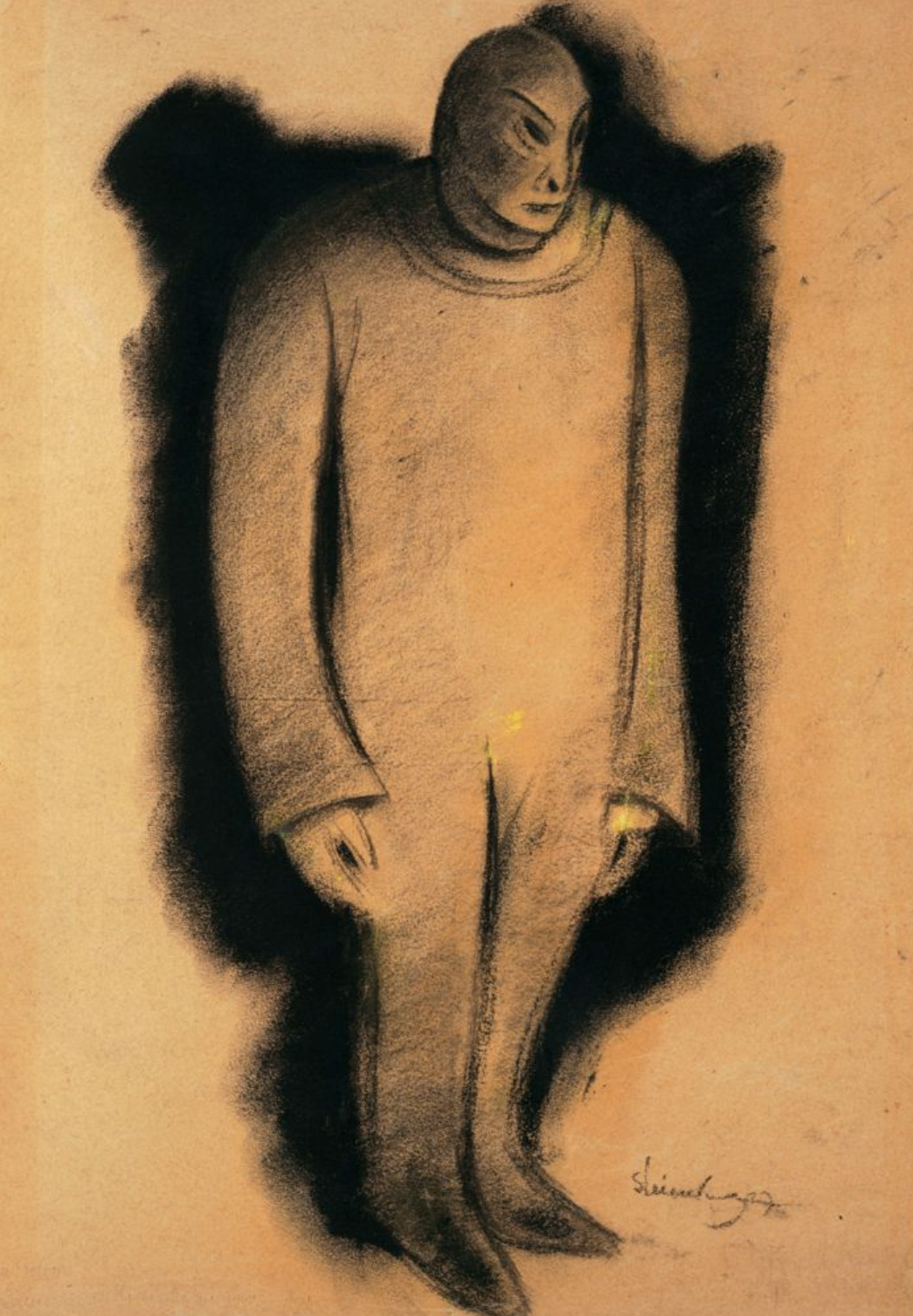

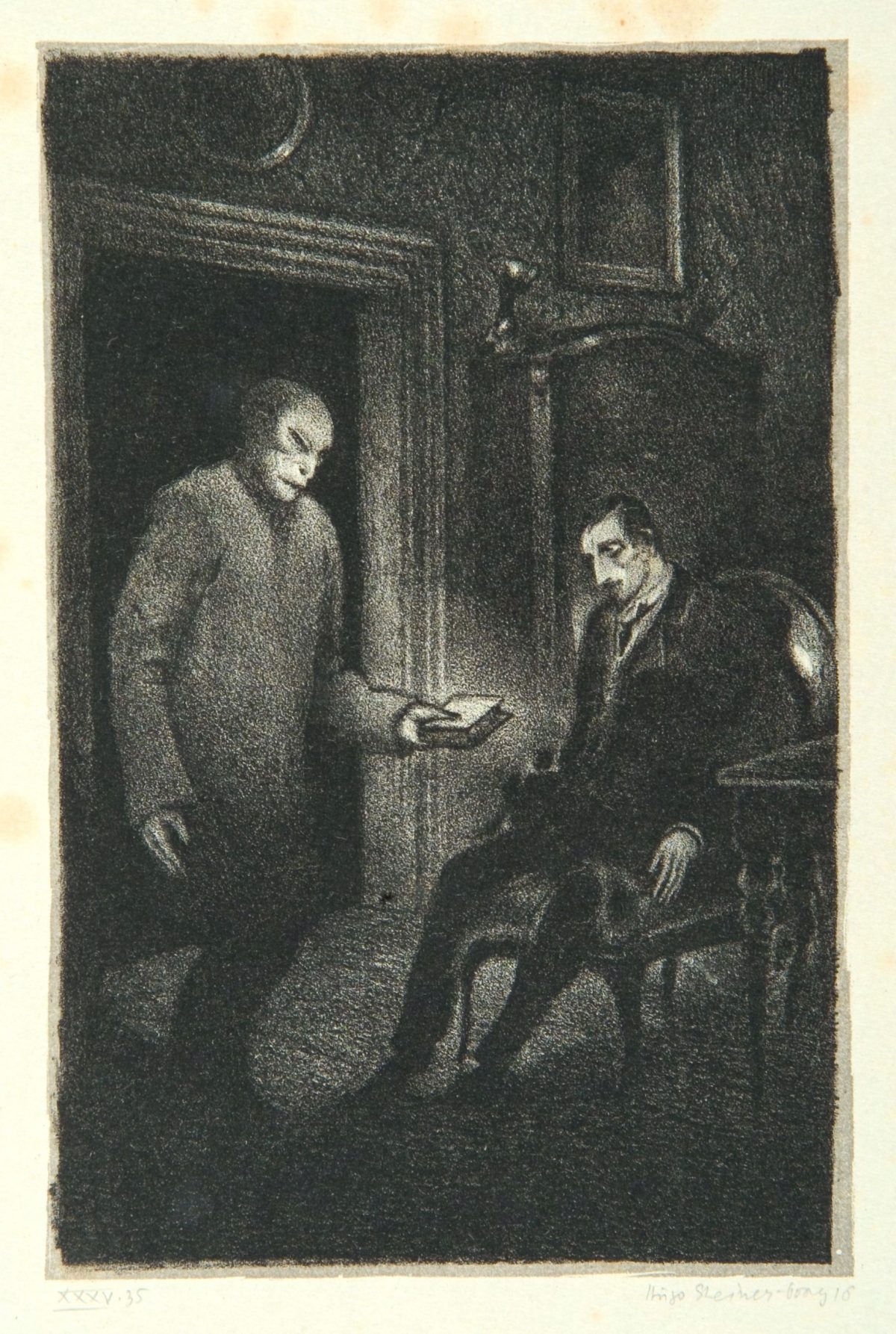

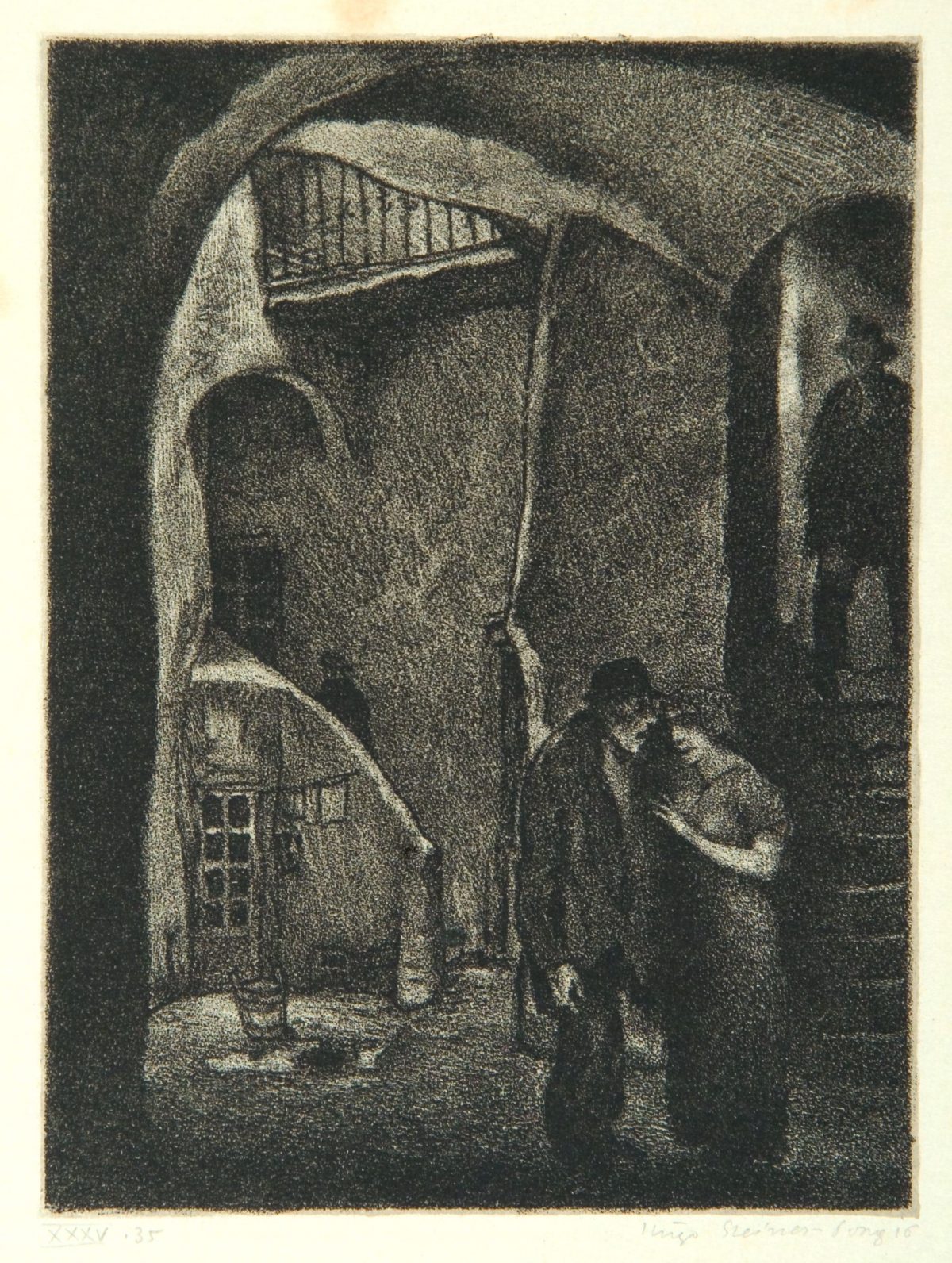

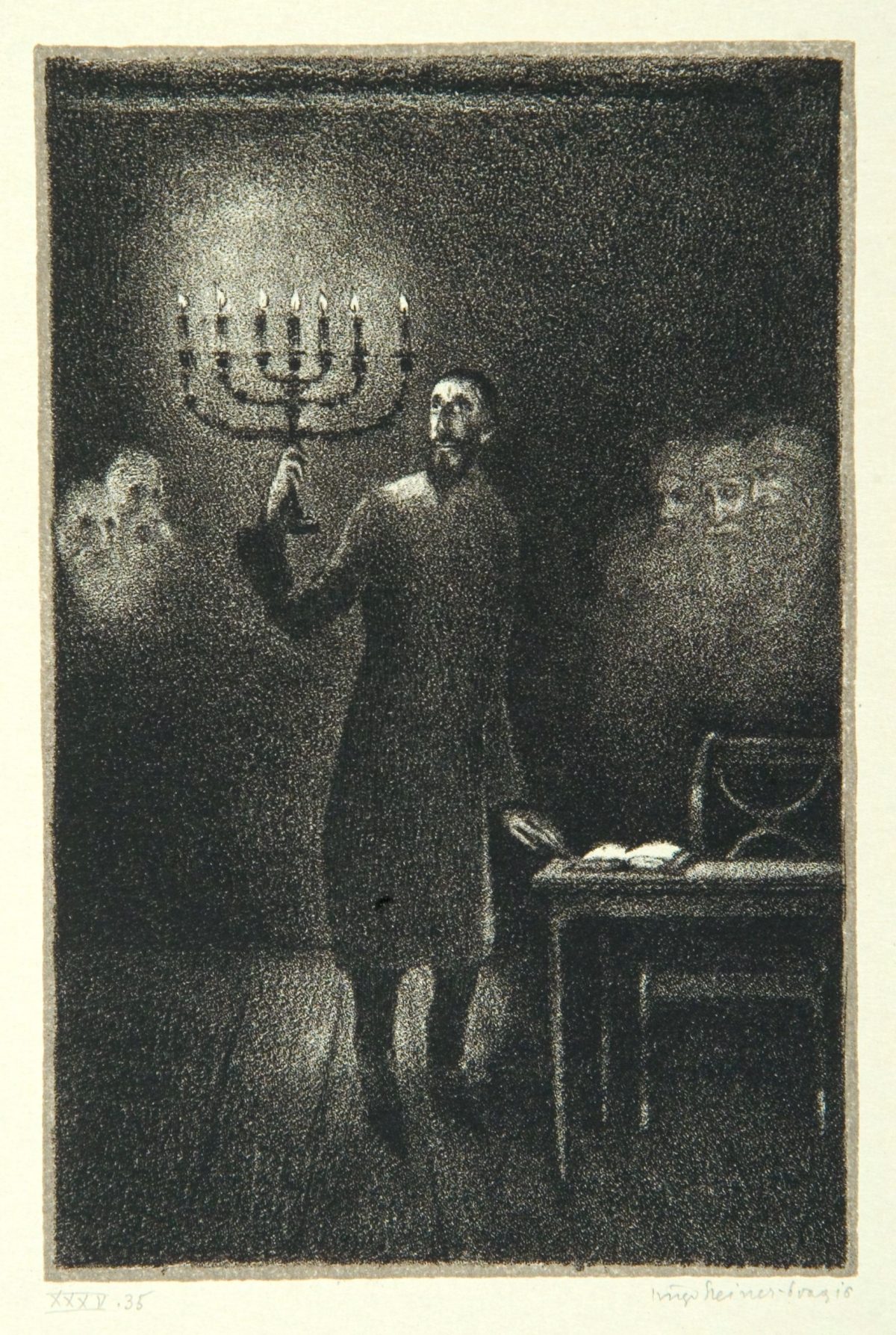

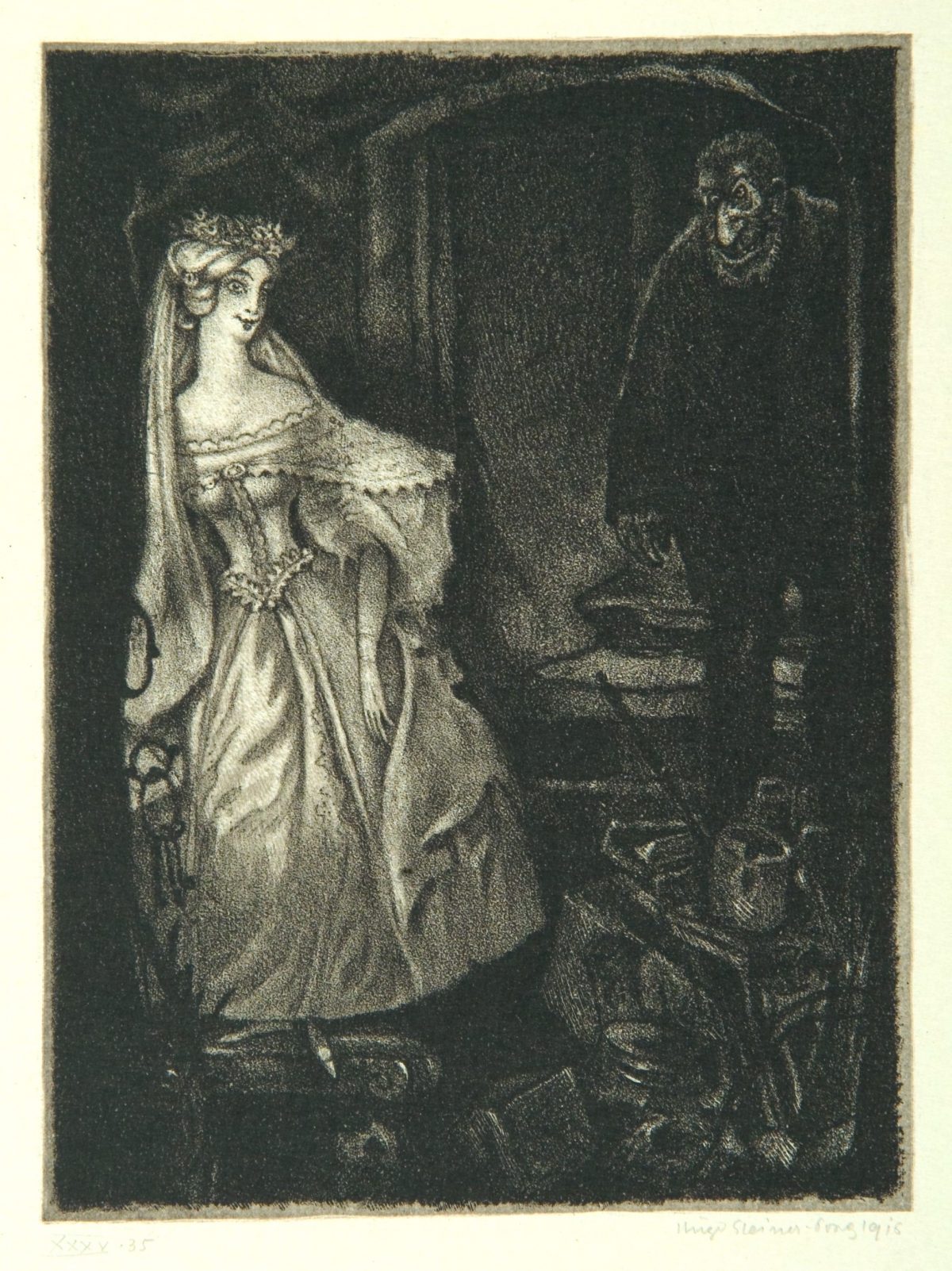

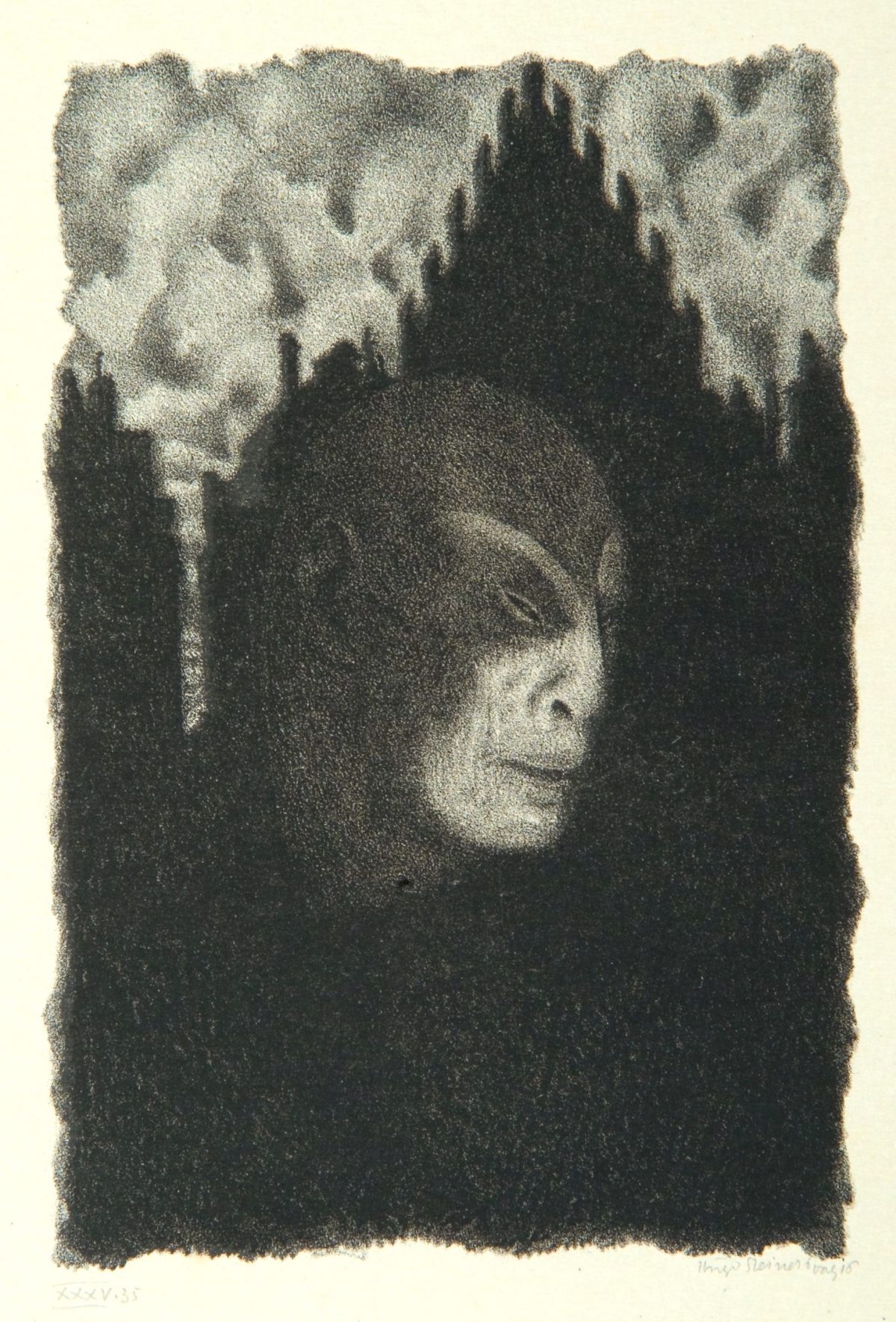

The Golem, as conceived by Hugo Steiner-Prag, for Gustav Meyrink’s novel Der Golem.

Readers may recognise the Golem from Kaddish, an episode of the science fiction television series The X-Files. In that show, a Jewish man is murdered by racists. Soon after, one of the assailants is strangled to death. Agent Mulder is convinced that the Golem is attempting to avenge the murder.

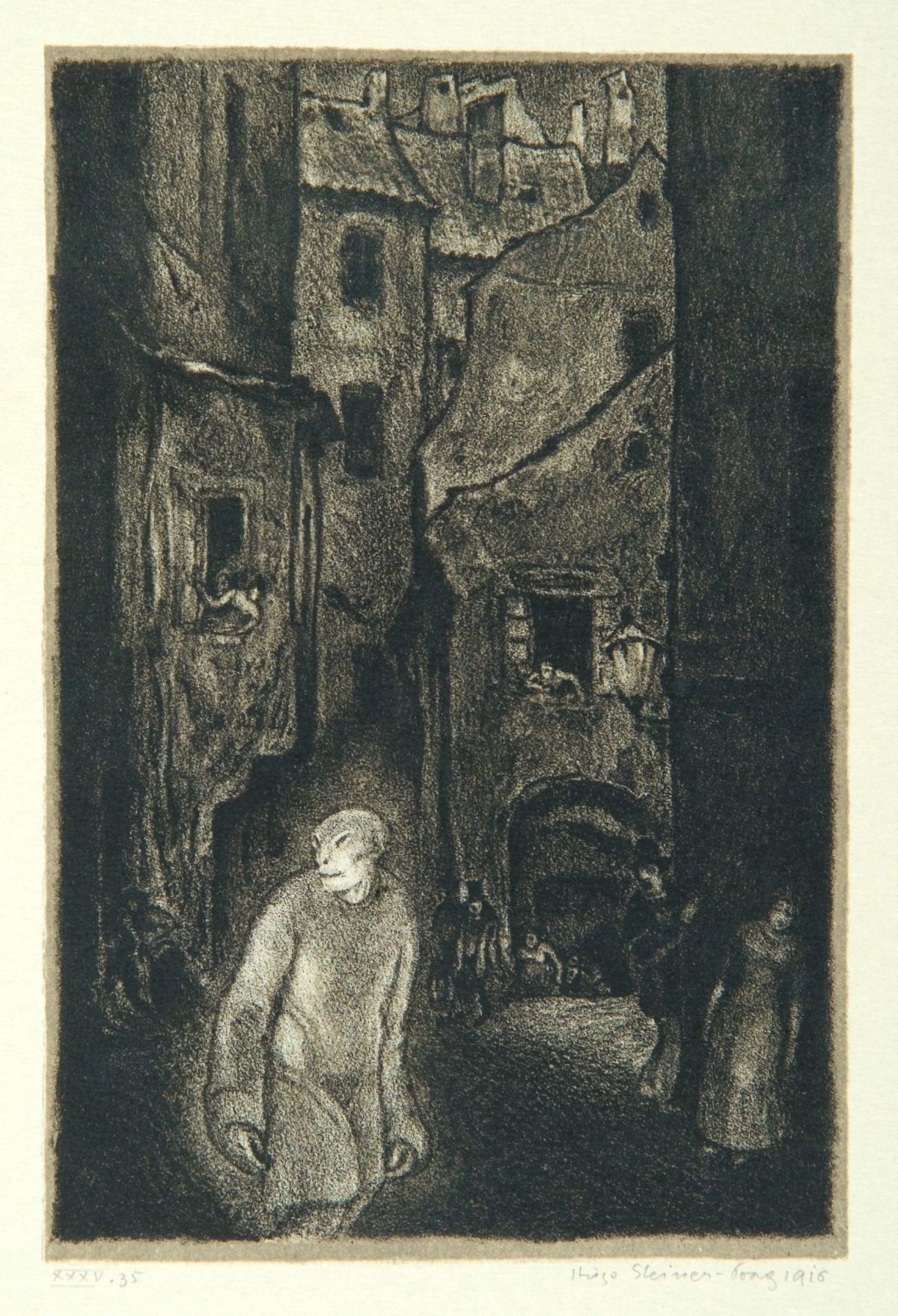

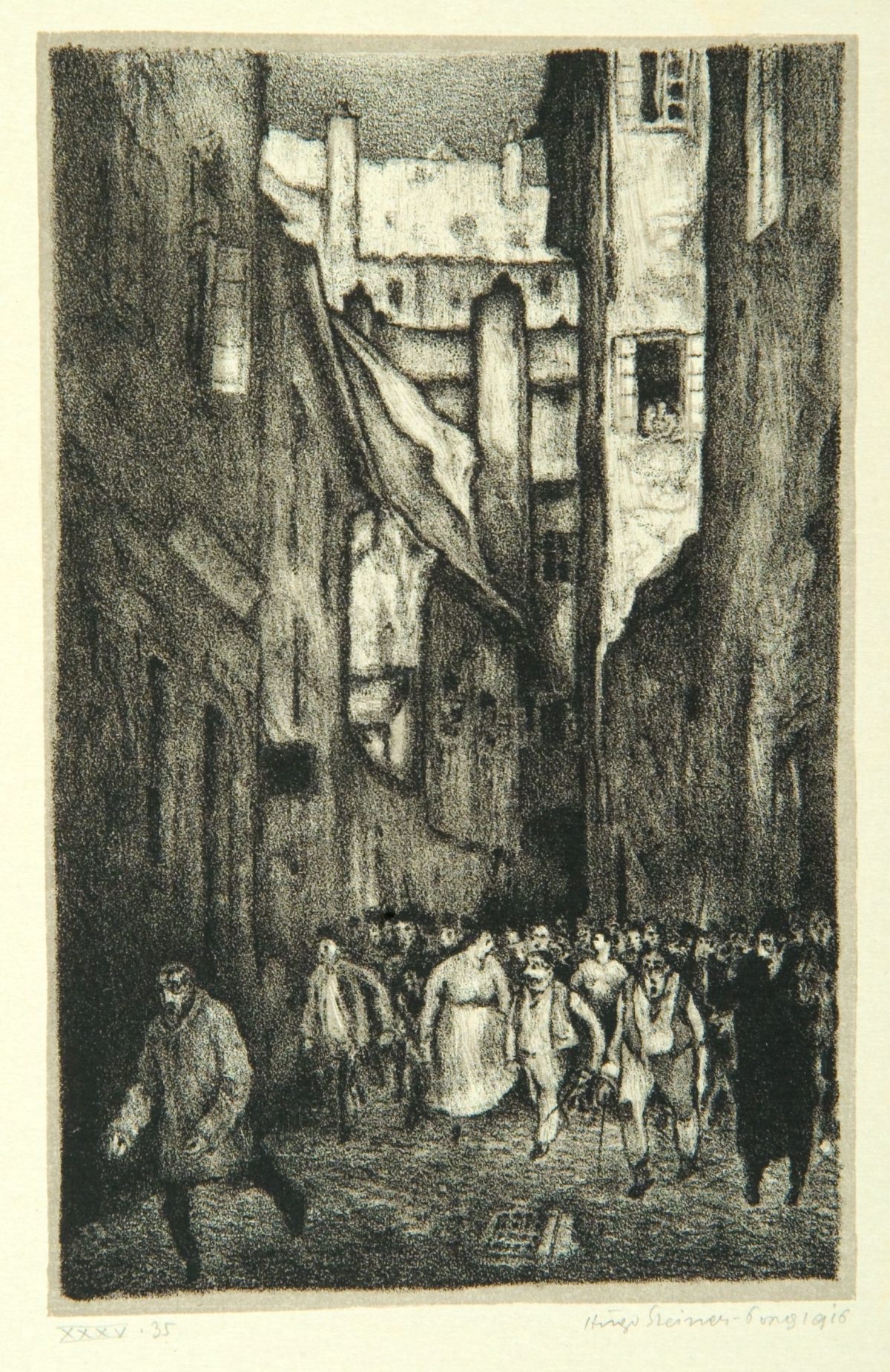

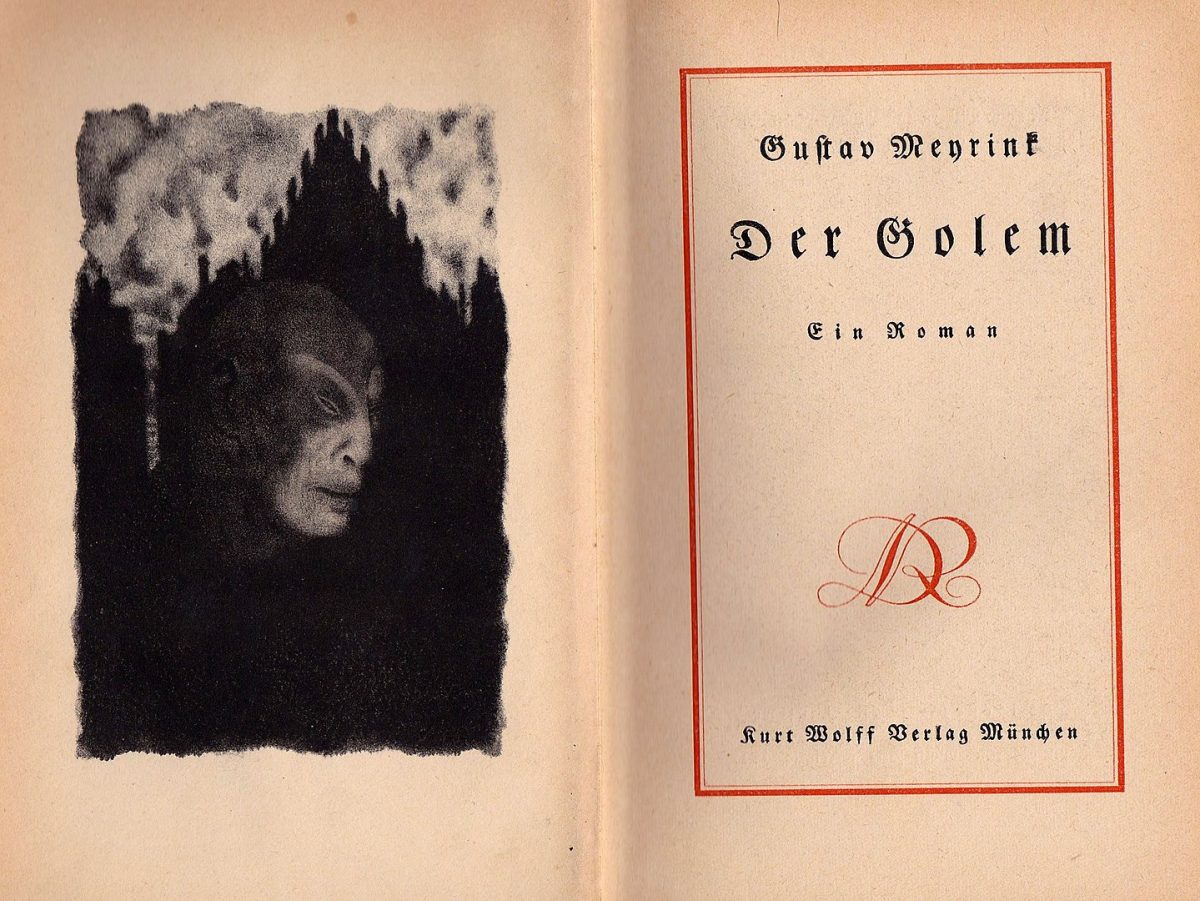

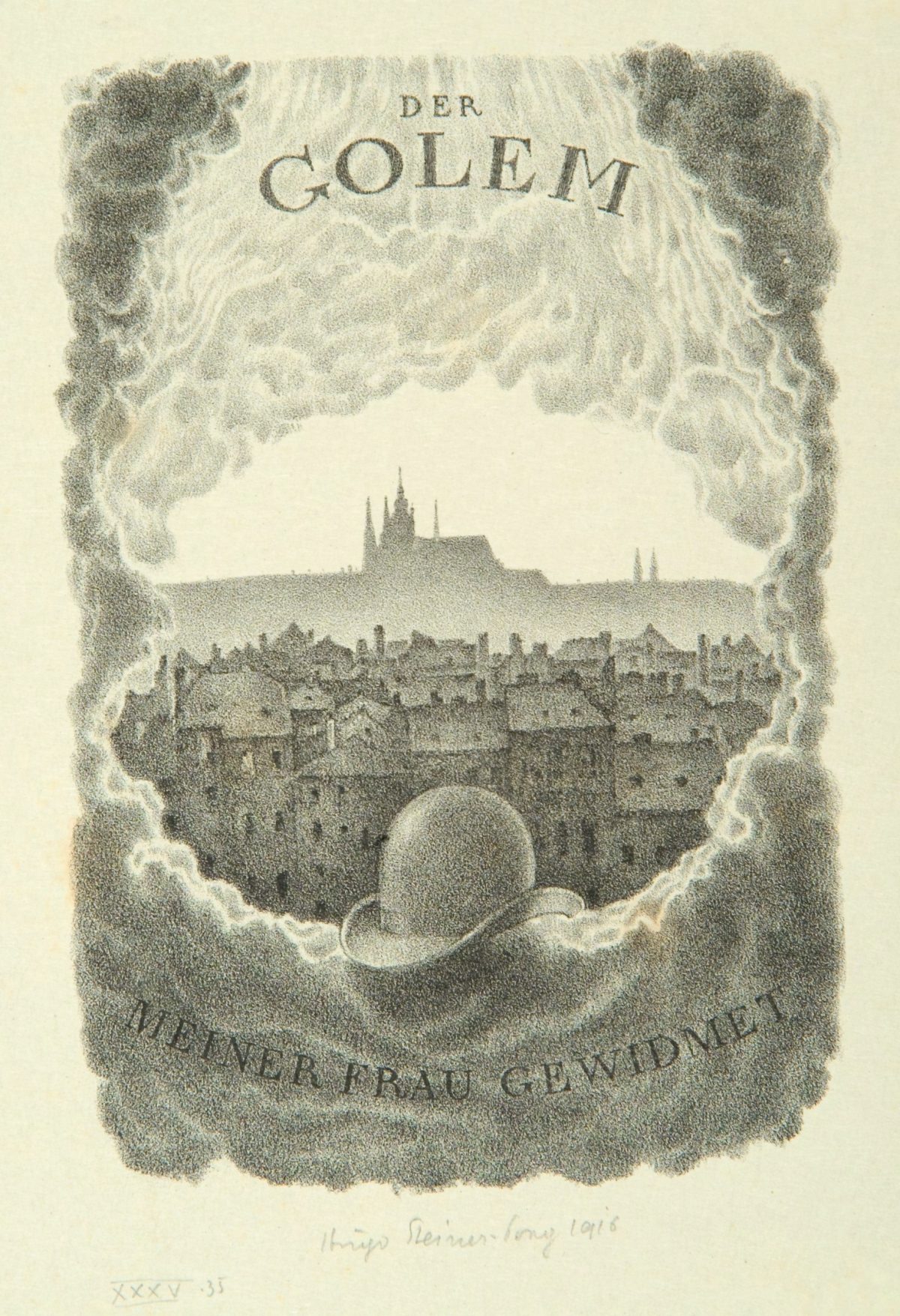

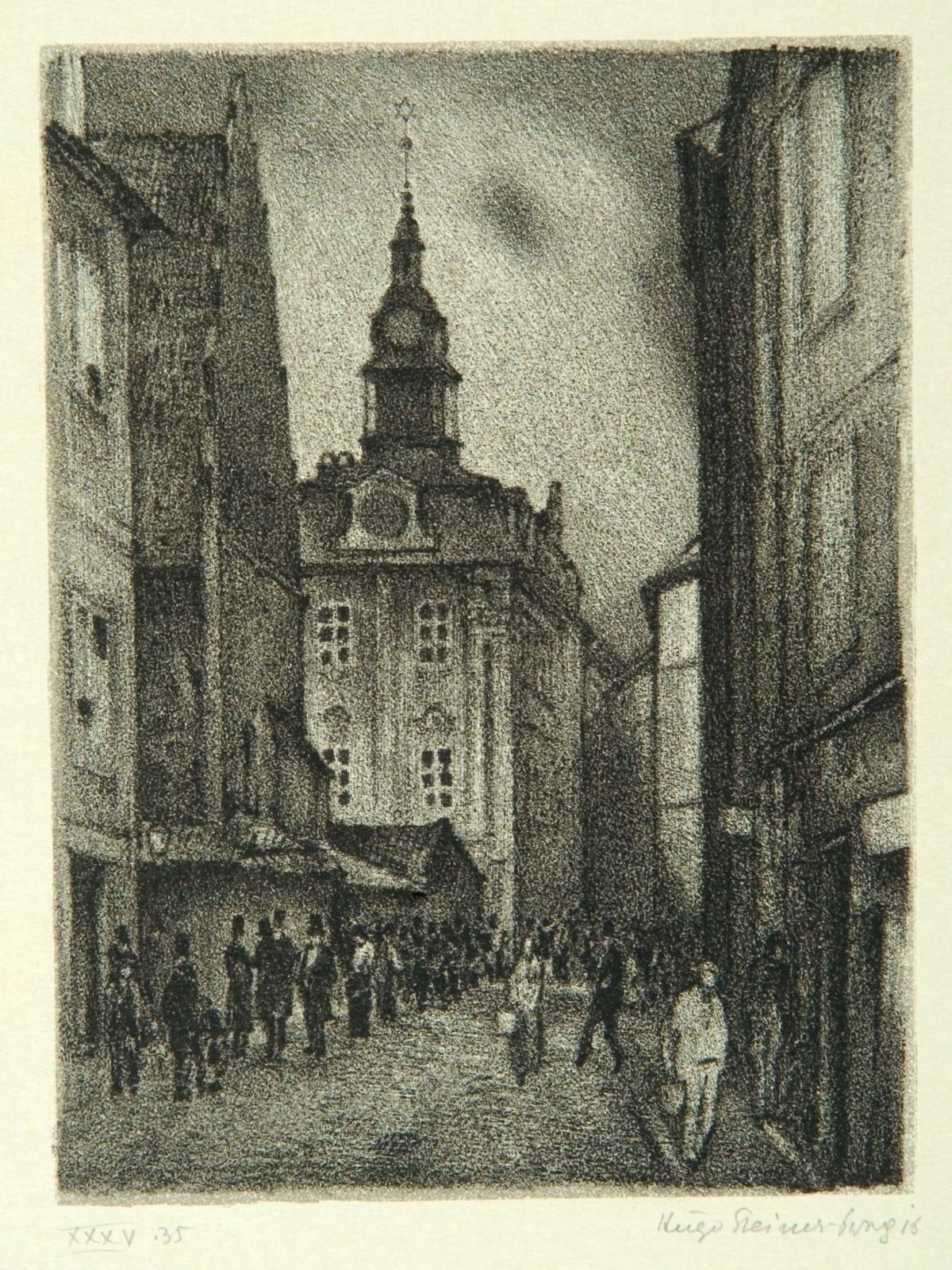

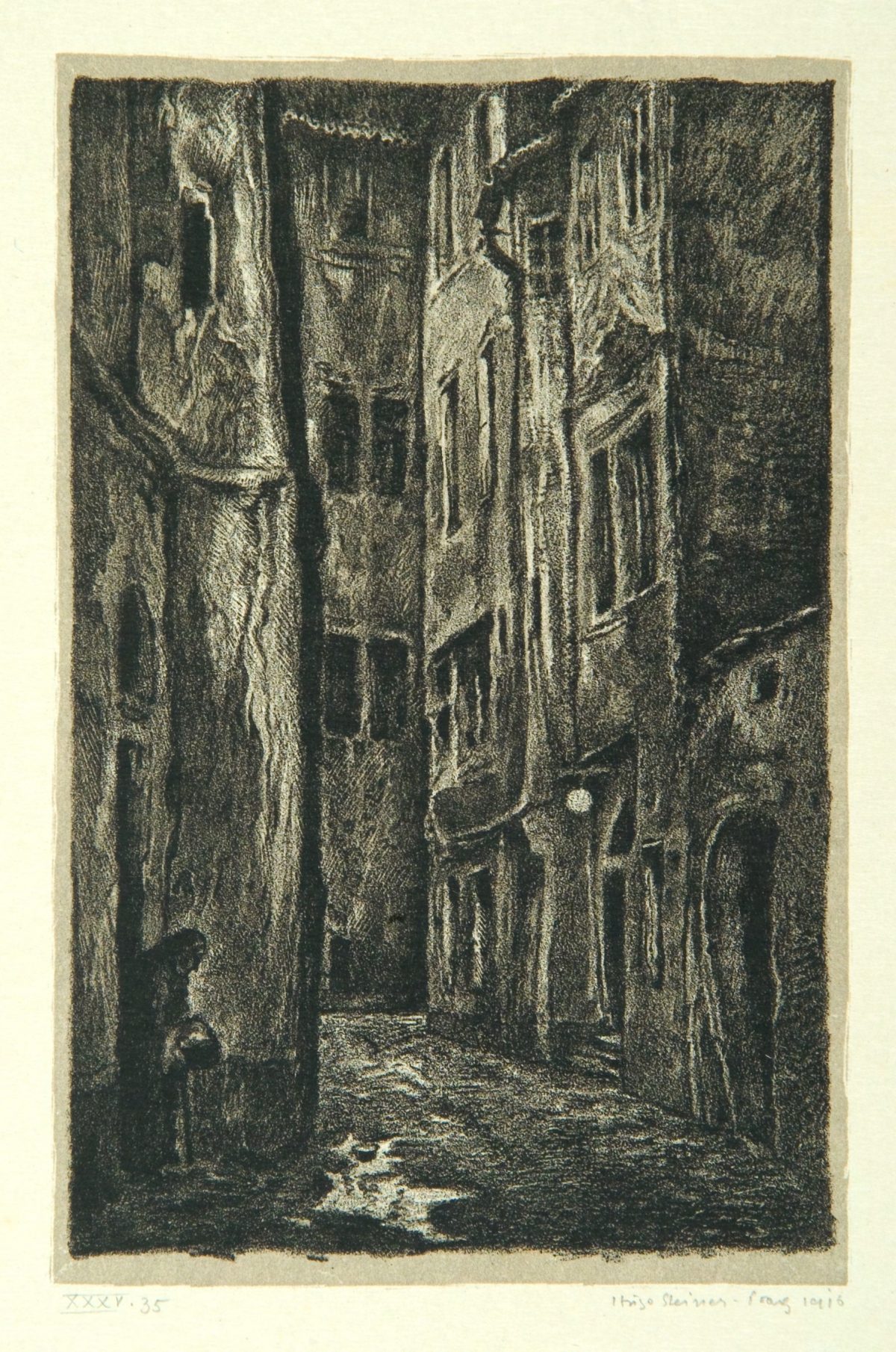

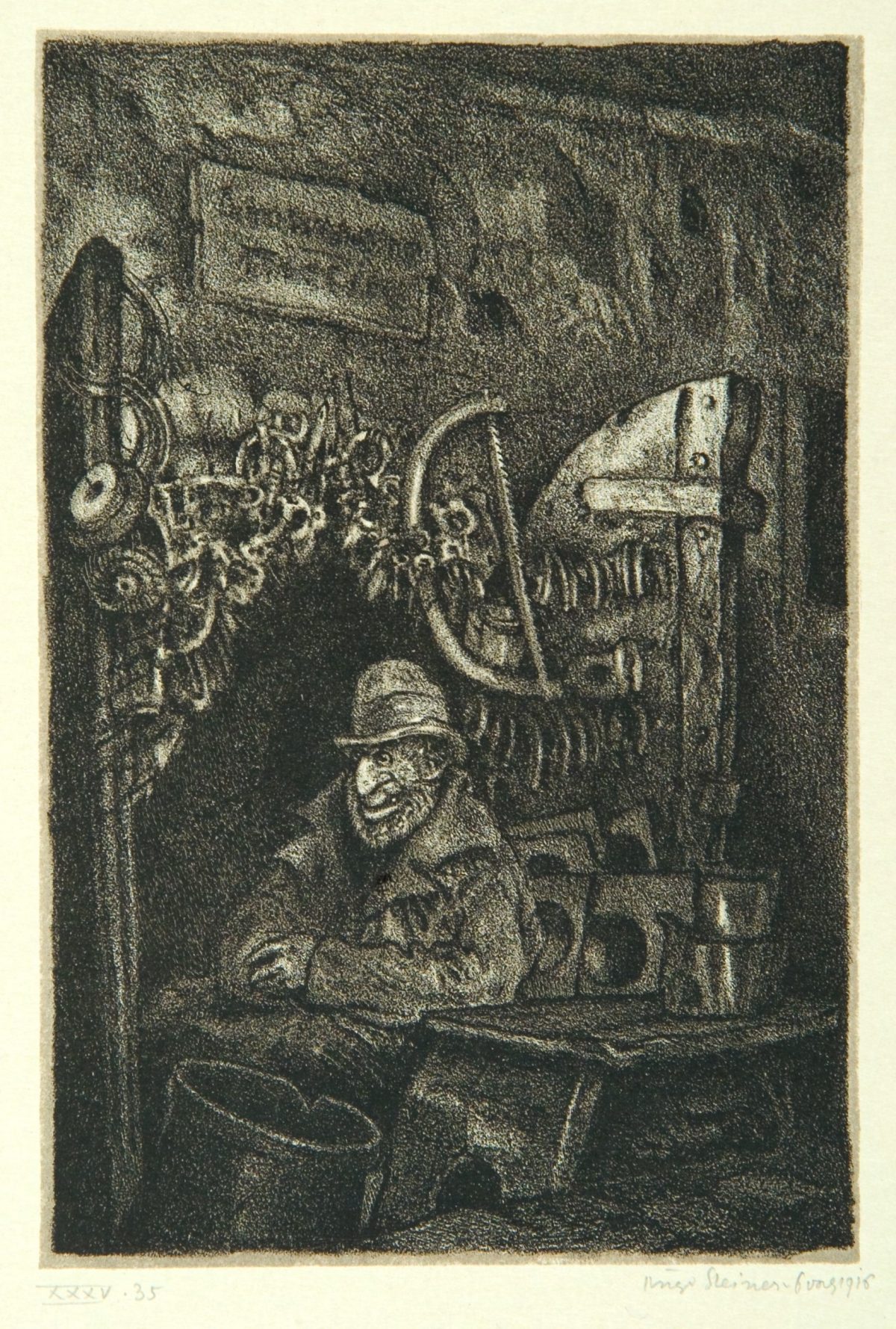

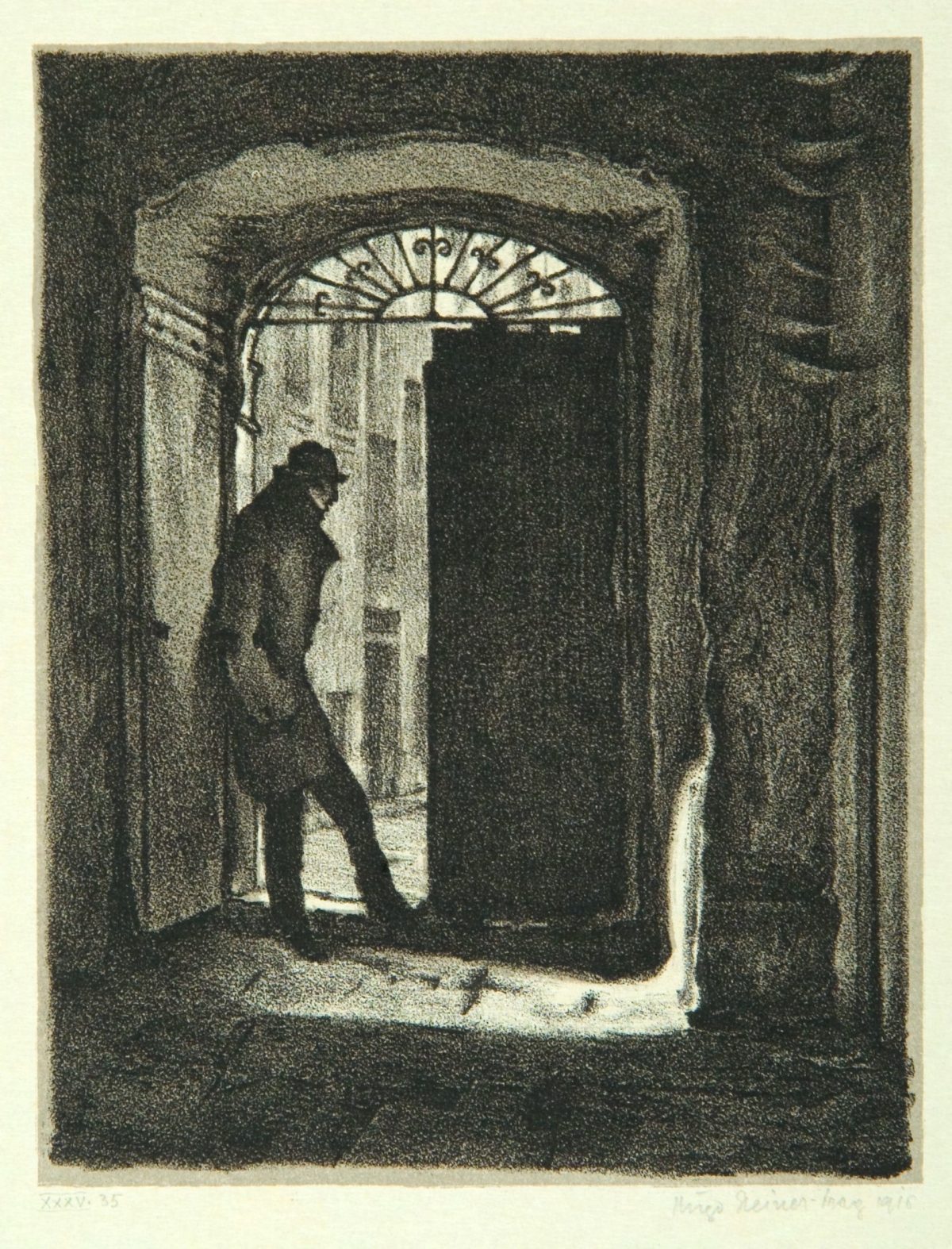

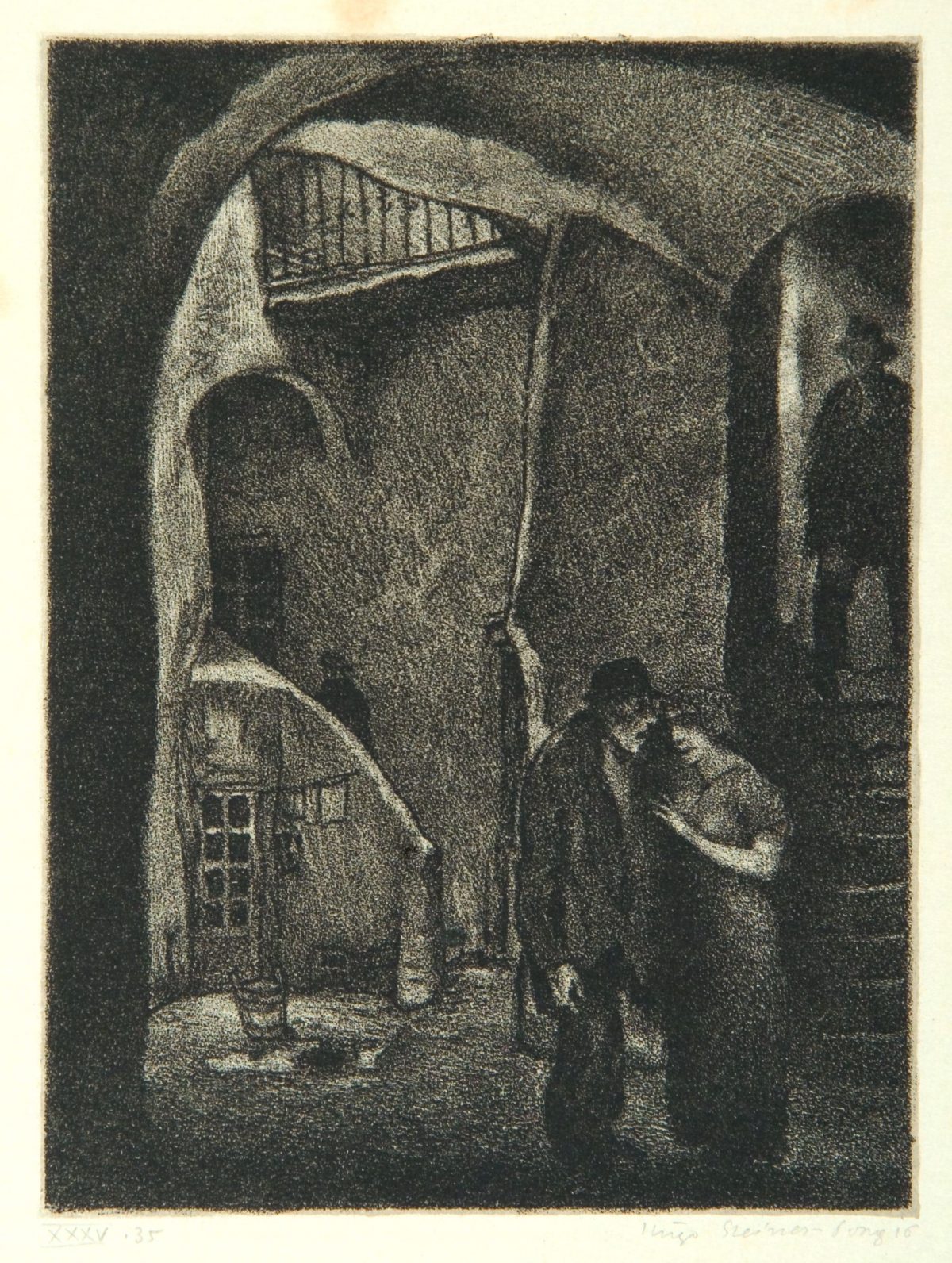

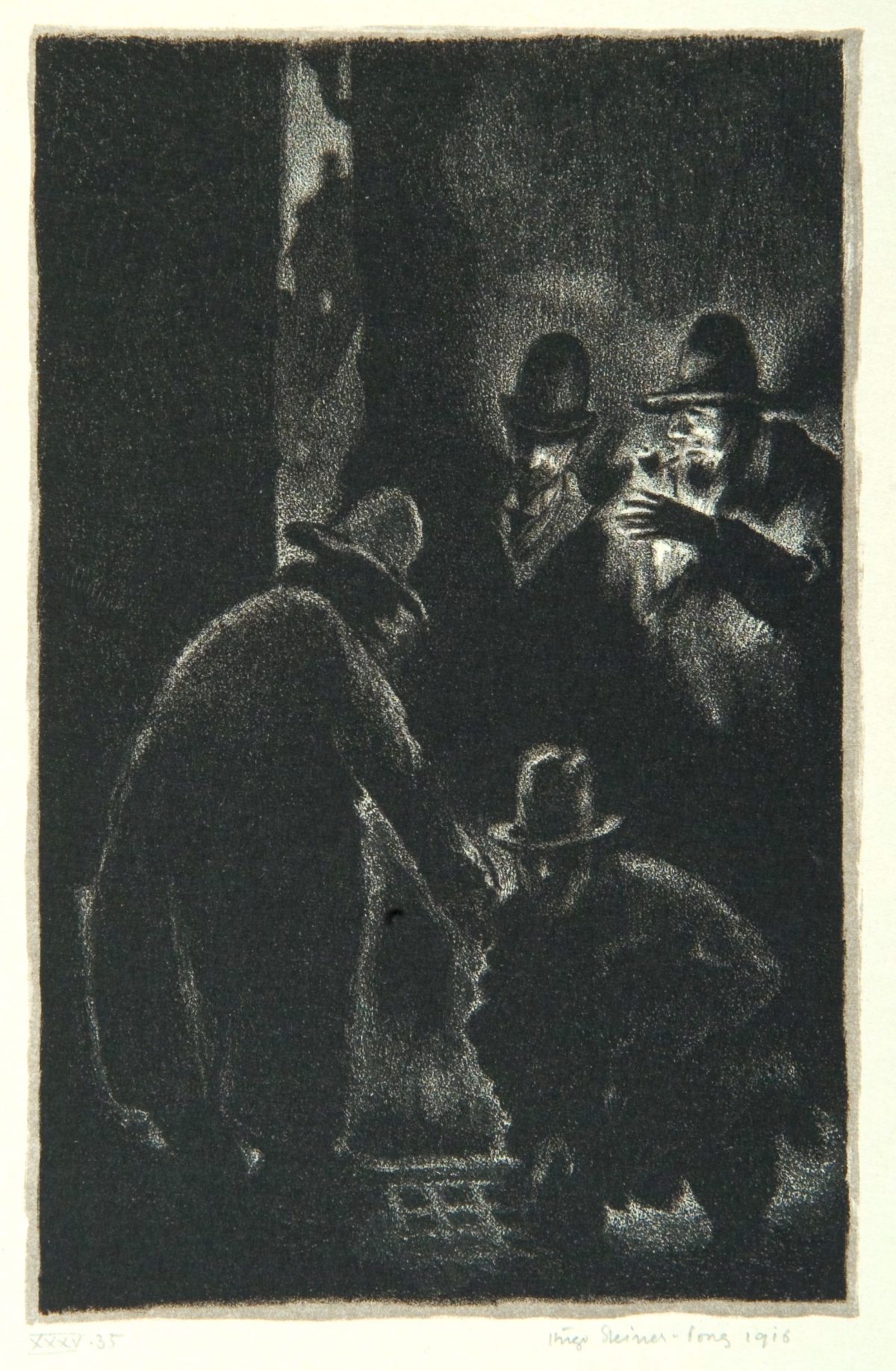

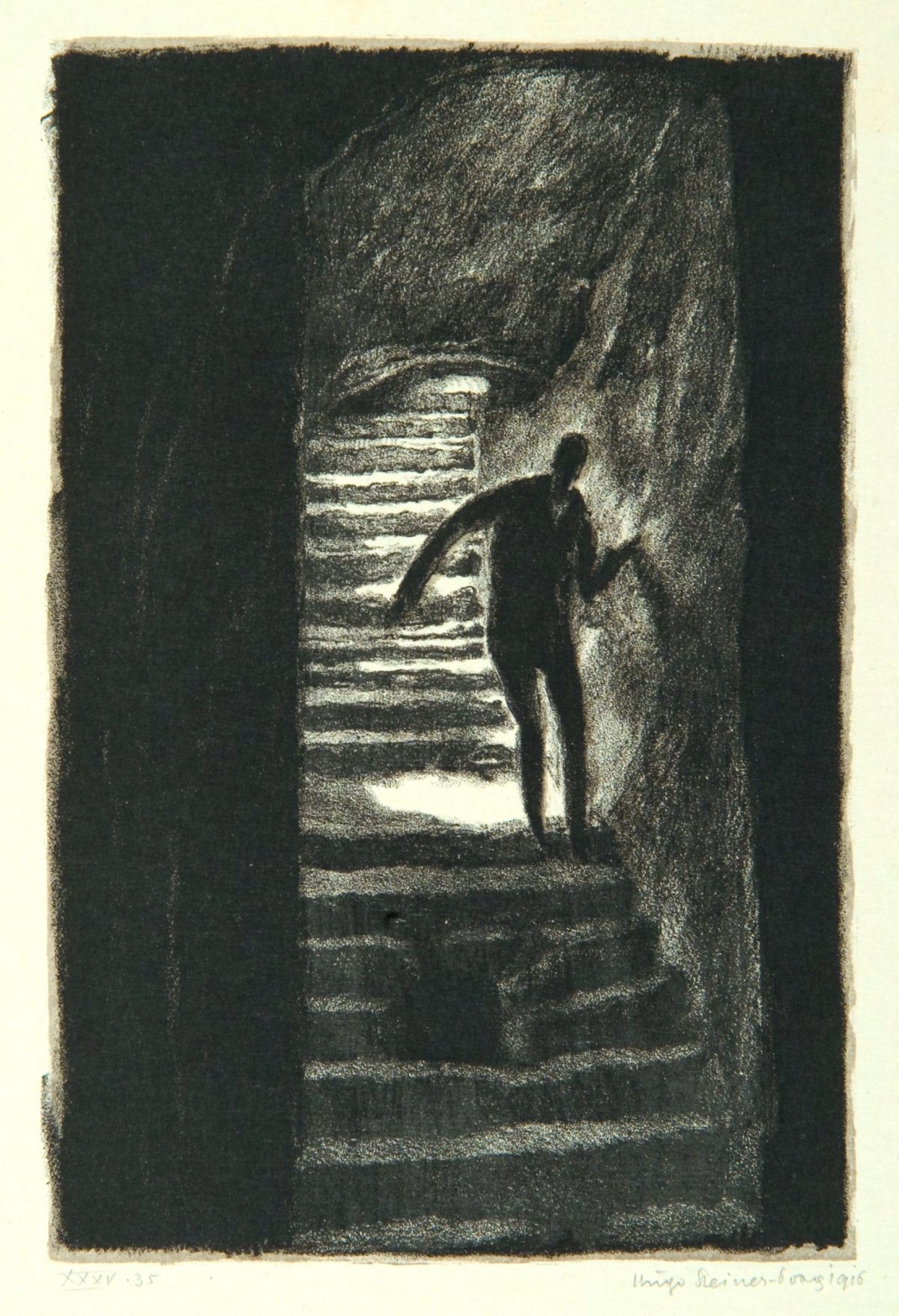

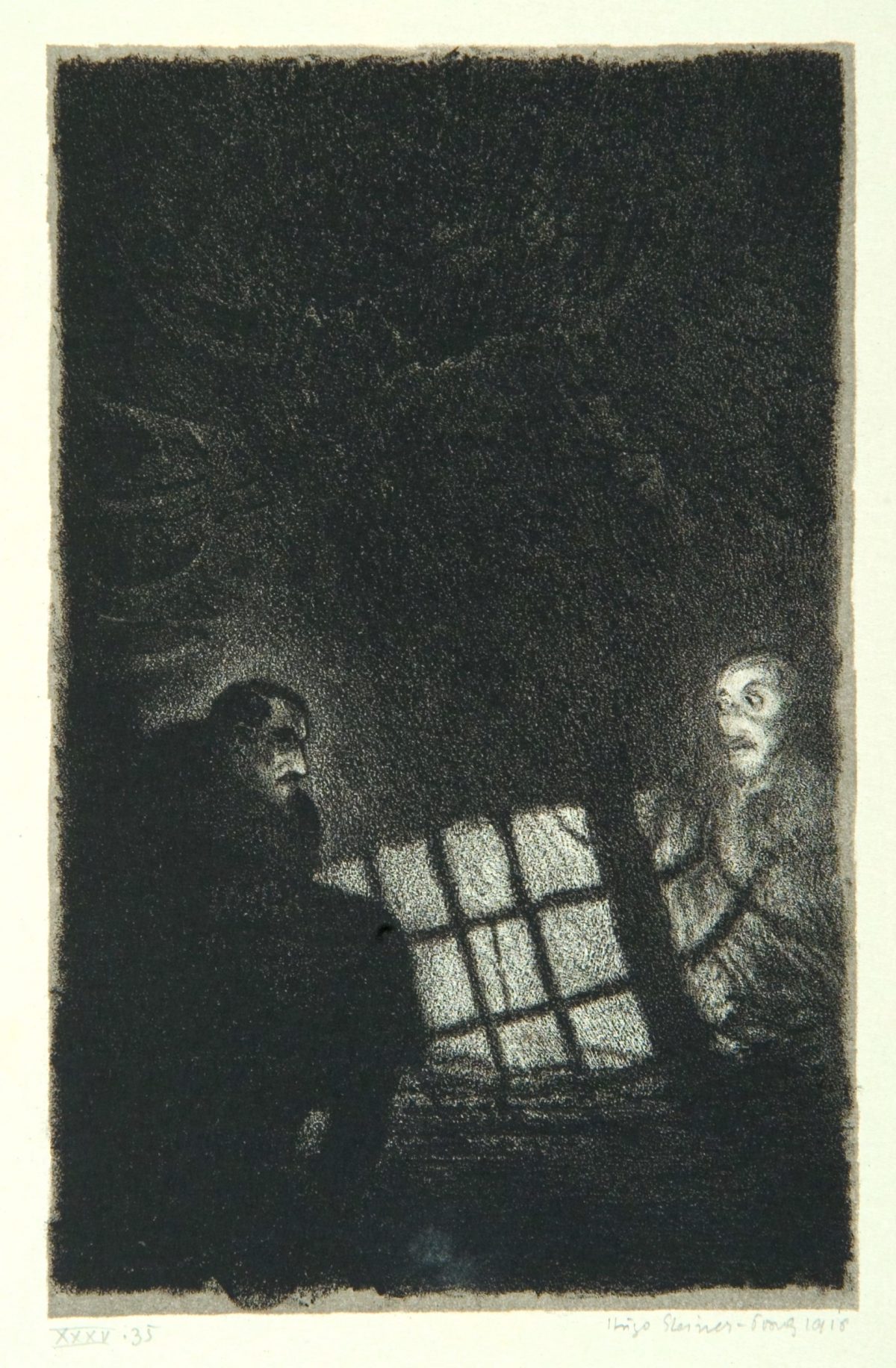

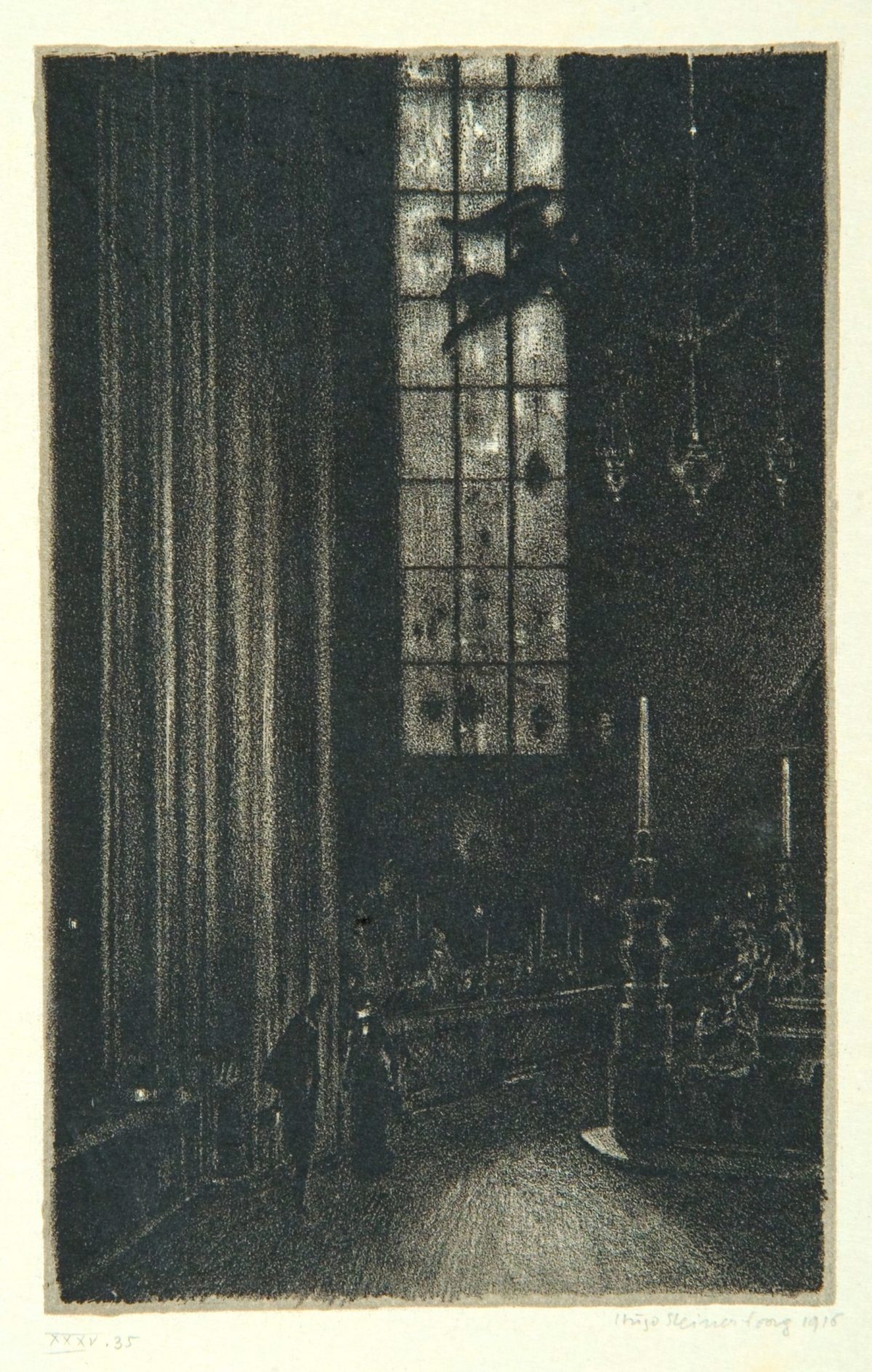

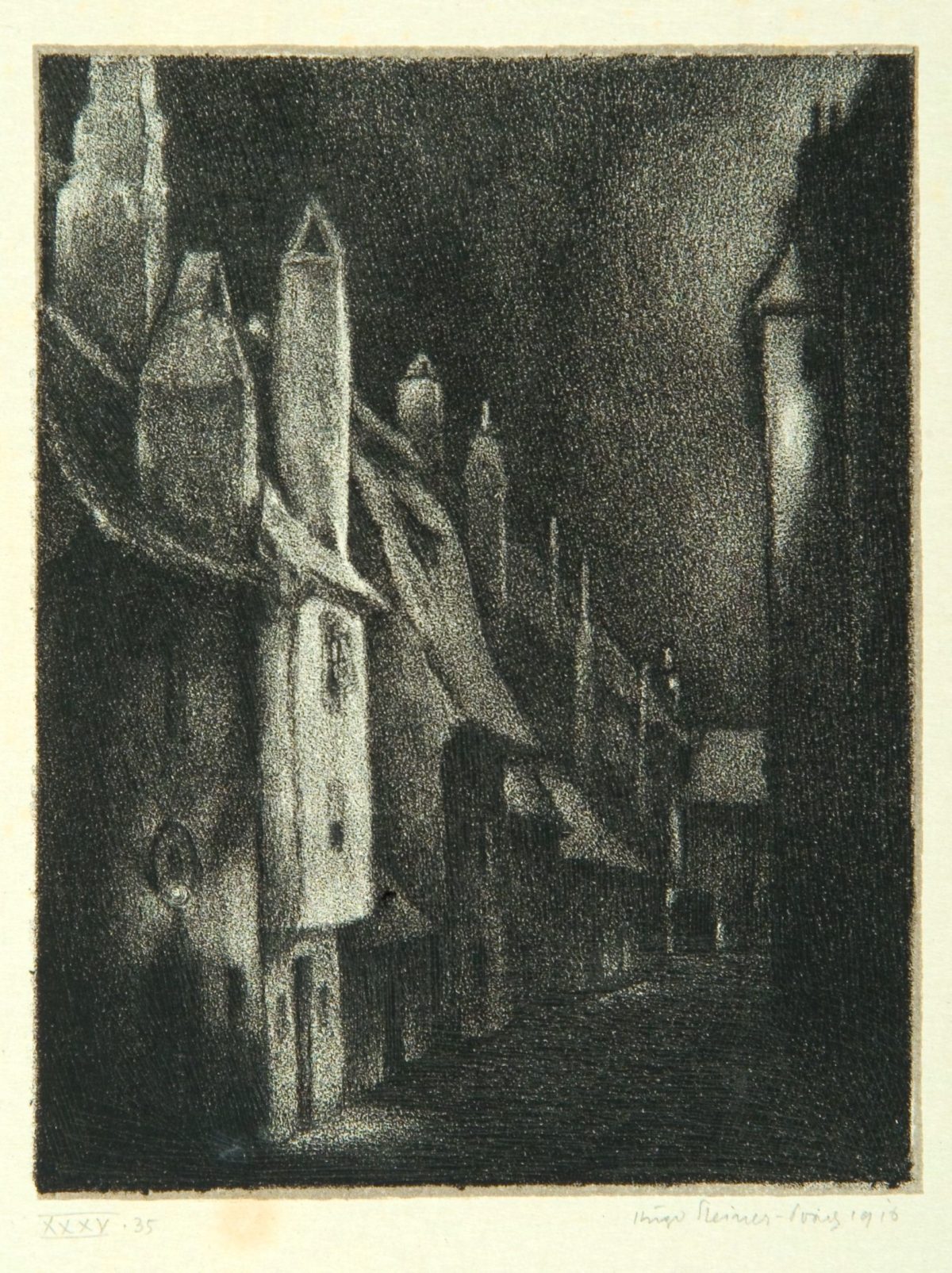

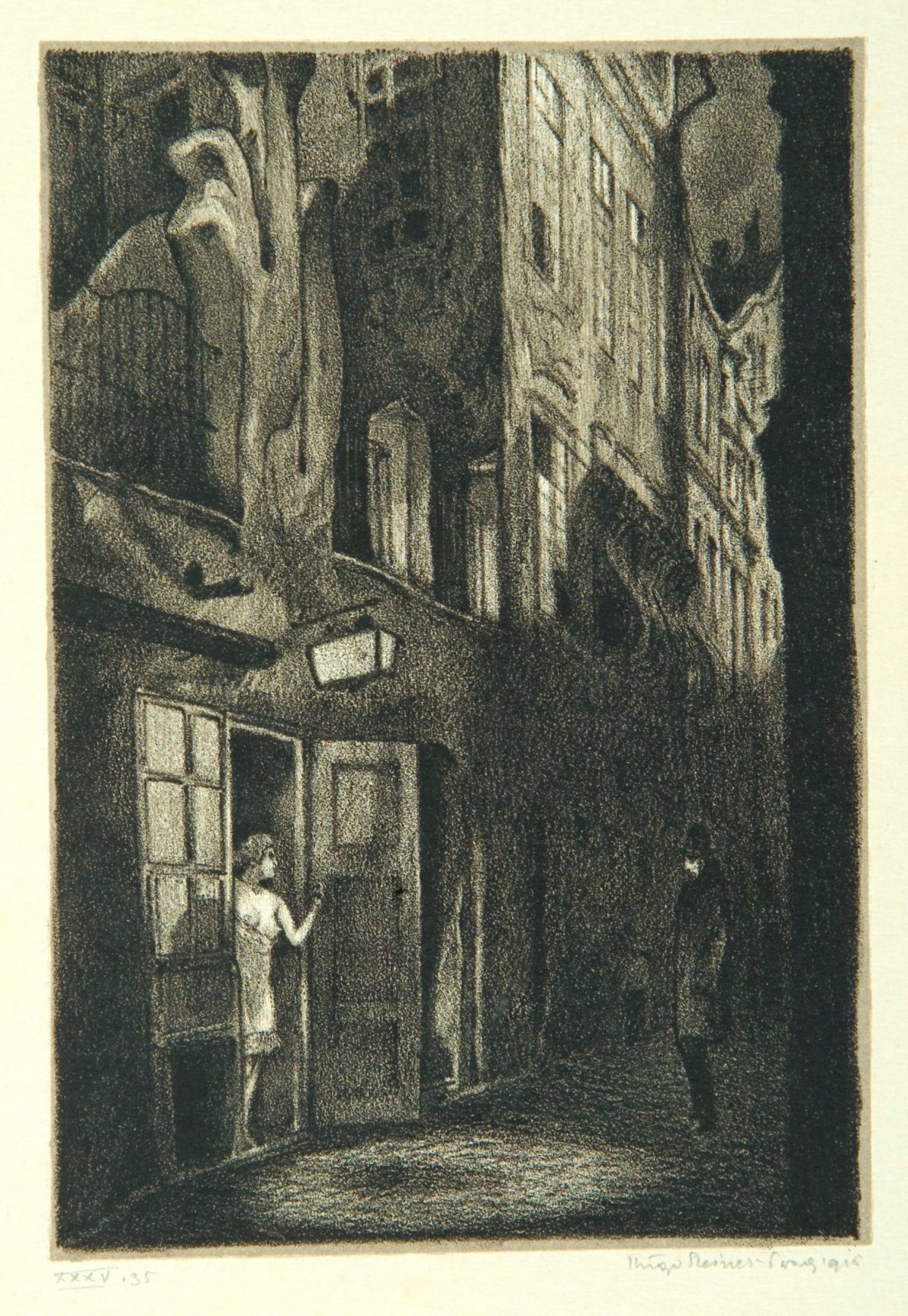

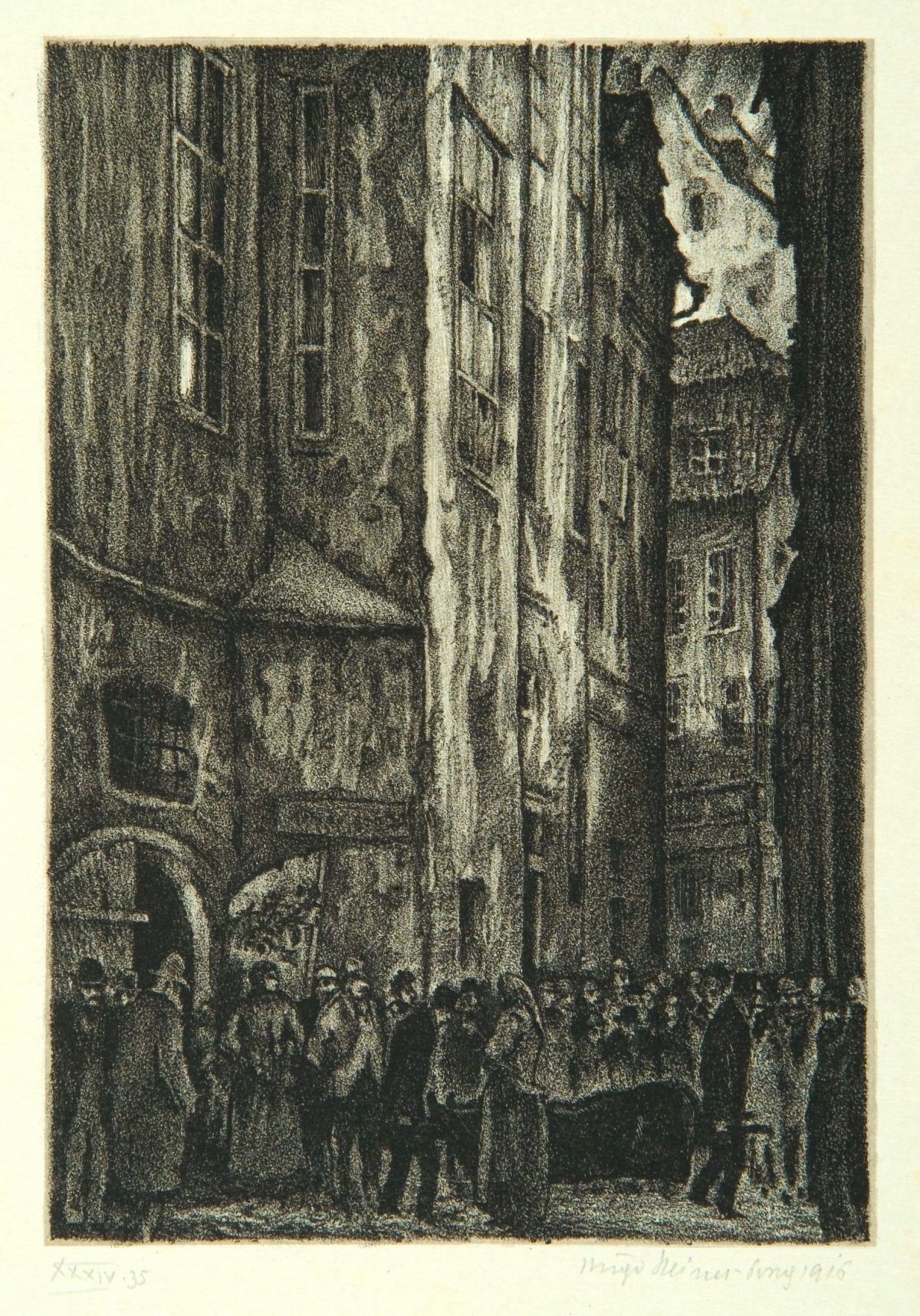

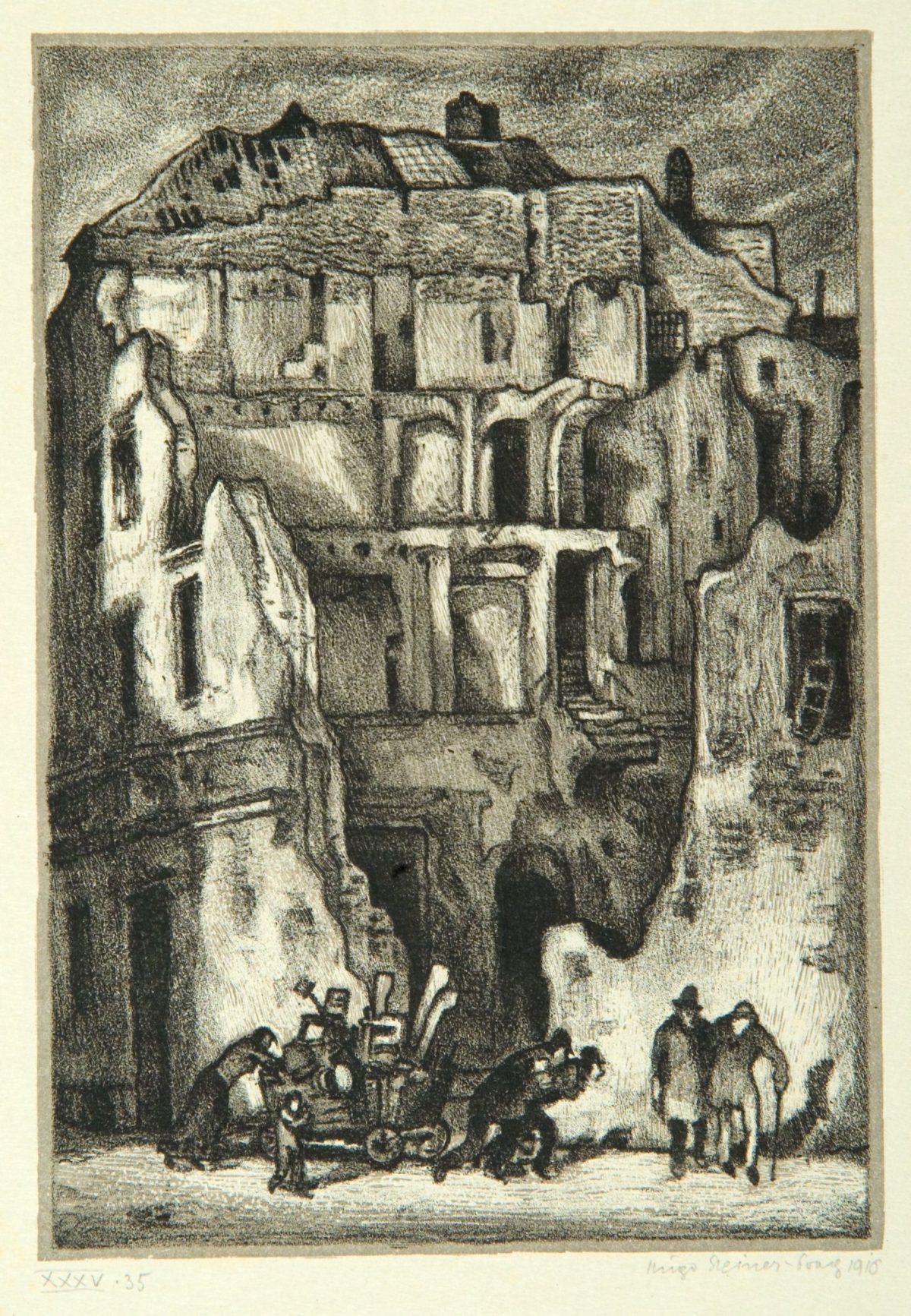

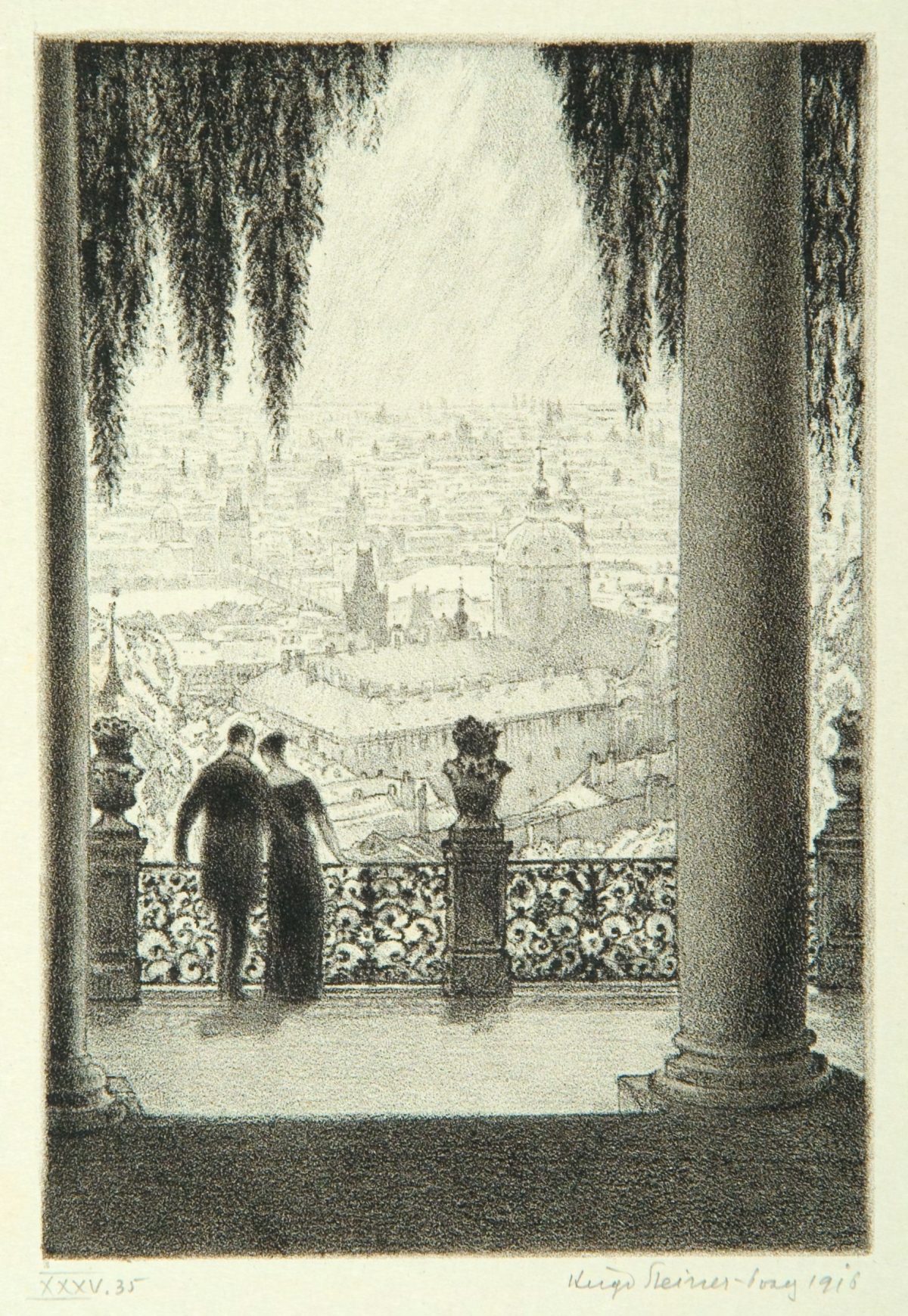

Here we show atmospheric illustrations of the Golem as conceived by Prague-born artist Hugo Steiner-Prag (1880 – 1945) for Gustav Meyrink’s novel Der Golem, 1915.

Steiner-Prag’s place of birth is relevant to this slice of Jewish folklore. The story goes that in the late 16th Century, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel of Prague, also known as the Maharal (the Hebrew acronym of “Moreinu ha-Rav Loew”; ‘Our Teacher, Rabbi Loew’), created a Golem of clay from the banks of the Vltava River and brought it to life through rituals and Hebrew incantations to defend the Prague ghetto from the frequent anti-Semitic attacks and pogroms.

If you too know the exact sequence of the 27 letters of God’s name, you too can make a Golem.

You can read more in The Golem by Elie Wiesel. The Nobel Prize winning writer tells the story of the Golem of Prague from the perspective of a gravedigger.

Meyrink’s novel, his first, was published as a serial from December 1913 to August 1914 in German periodical Die Weißen Blätter. Der Golem was then published in book form by Kurt Wolff of Leipzig, Germany. It was a hit, selling over 200,000 copies in its first year.

It’s a memorably and fascinatingly odd book. The story centres on the life of Athanasius Pernath, a jeweller and art restorer who lives in Prague’s Jewish ghetto. His story is experienced by an anonymous narrator, who mistakenly puts on the real Pernath’s hat and assumes his identity from 30 years before.

The book is magical, mystical, nightmarish, expressionist, mind-boggling stuff laced with a whiff of danger about what happens when you give life to the lifeless. The Golem might be there to help Jews, but with a mind of its own is just as likely to go berserk and smash the place up.

The anthropomorphic being is rarely witnessed in the book. Is it real? Is anything real? Maybe the Golem is a representative of the ghetto’s spirit and consciousness, conjured into life by the suffering that its inhabitants have endured over the centuries? Maybe the Golem is just too big to see?

What happened to it? Maybe, as legend has it, the rabbi sensed the danger, removed the word of God from its mouth and locked the creation inside the city’s Old New Synagogue’s attic. They say no-one ventured inside until a Nazi burst in and was never seen nor heard from again. No-one’s been inside since.

The_Hahnpassgass

American writer H.P. Lovecraft loved it. Howard Phillips Lovecraft (August 20, 1890 – March 15, 1937), best known for his creation of the Cthulhu Mythos, writes about the book in his essay Supernatural Horror in Literature, first published in August 1927:

A very flourishing, though till recently quite hidden, branch of weird literature is that of the Jews, kept alive and nourished in obscurity by the sombre heritage of early Eastern magic, apocalyptic literature, and cabbalism. The Semitic mind, like the Celtic and Teutonic, seems to possess marked mystical inclinations; and the wealth of underground horror-lore surviving in ghettoes and synagogues must be much more considerable than is generally imagined.

Cabbalism itself, so prominent during the Middle Ages, is a system of philosophy explaining the universe as emanations of the Deity, and involving the existence of strange spiritual realms and beings apart from the visible world, of which dark glimpses may be obtained through certain secret incantations. Its ritual is bound up with mystical interpretations of the Old Testament, and attributes an esoteric significance to each letter of the Hebrew alphabet – a circumstance which has imparted to Hebrew letters a sort of spectral glamour and potency in the popular literature of magic.

Jewish folklore has preserved much of the terror and mystery of the past, and when more thoroughly studied is likely to exert considerable influence on weird fiction.

The best examples of its literary use so far are the German novel The Golem, by Gustav Meyrink, and the drama The Dybbuk, by the Jewish writer using the pseudonym “Ansky”. The former, with its haunting shadowy suggestions of marvels and horrors just beyond reach, is laid in Prague, and describes with singular mastery that city’s ancient ghetto with its spectral, peaked gables. The name is derived from a fabulous artificial giant supposed to be made and animated by mediaeval rabbis according to a certain cryptic formula.”

Steiner-Prag could have used a Golem in later years. After a period in Paris, in 1933 he returned to Germany, where he’d studied and worked. Despite having converted from Judaism to Catholicism nearly thirty years before, the Nazis terminated his post at the Leipzig art academy on the grounds of his Jewish ancestry. Steiner-Prag returned home to Prague where he designed stage sets and ran Officina Pragensis, his school for book illustration and graphic design. In 1938, Steiner-Prag took an opportunity to open a similar illustration school in Stockholm, Sweden, farther away from the Nazis. He was accompanied by his Jewish lover Eleanor Fiesenberg.

In 1940, Fiesenberg emigrated to the United States and was soon followed by Steiner-Prag. The two settled in New Haven, Connecticut and married on January 3, 1942. Steiner-Prag began teaching at the Graphic Arts Division of New York University. He died on September 10, 1945.

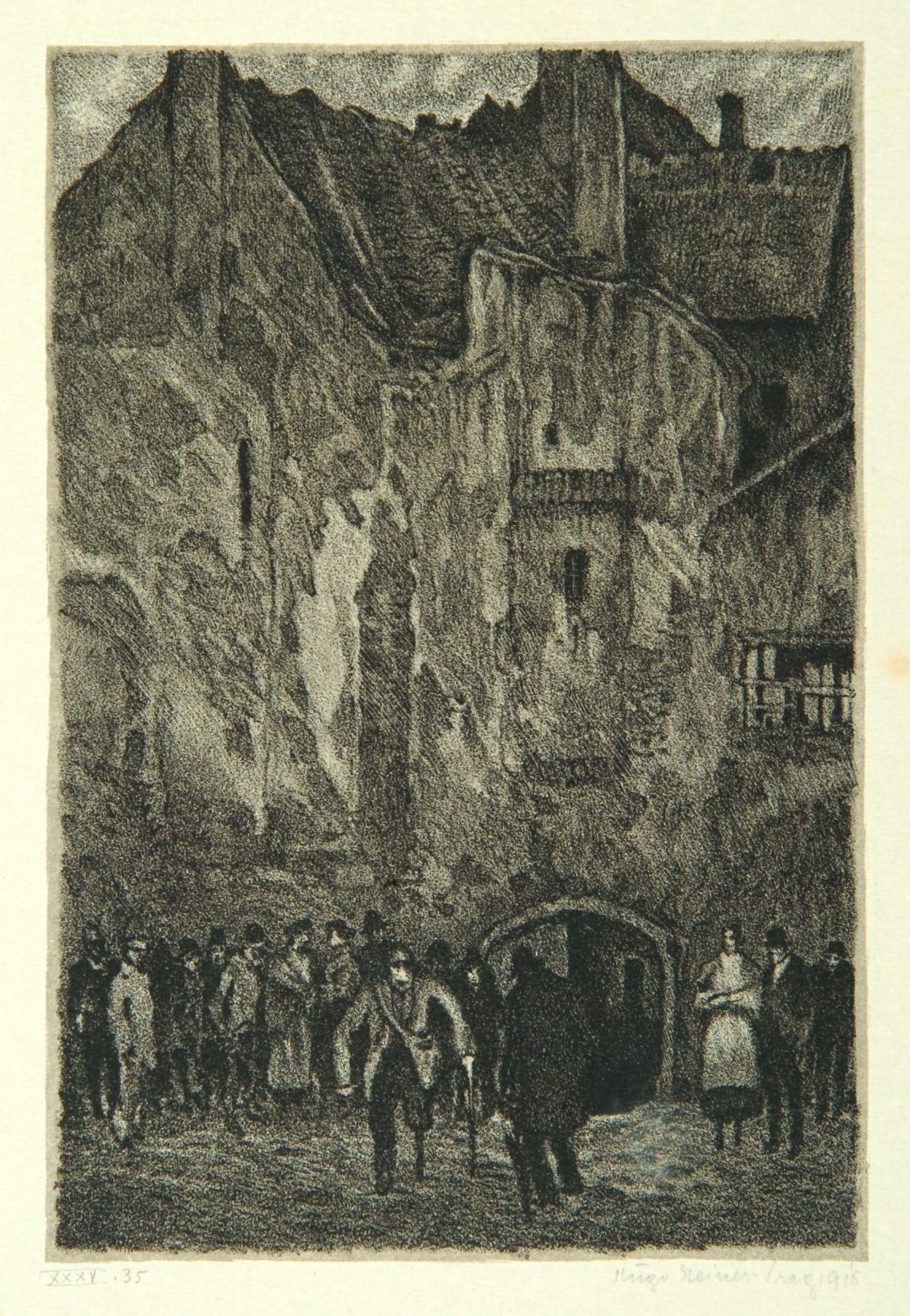

In The Ghetto

The Book Ibbur

Aron Wassertrum

Student Charousek

Vice

Vice

Cry for Help

The Road of Fear

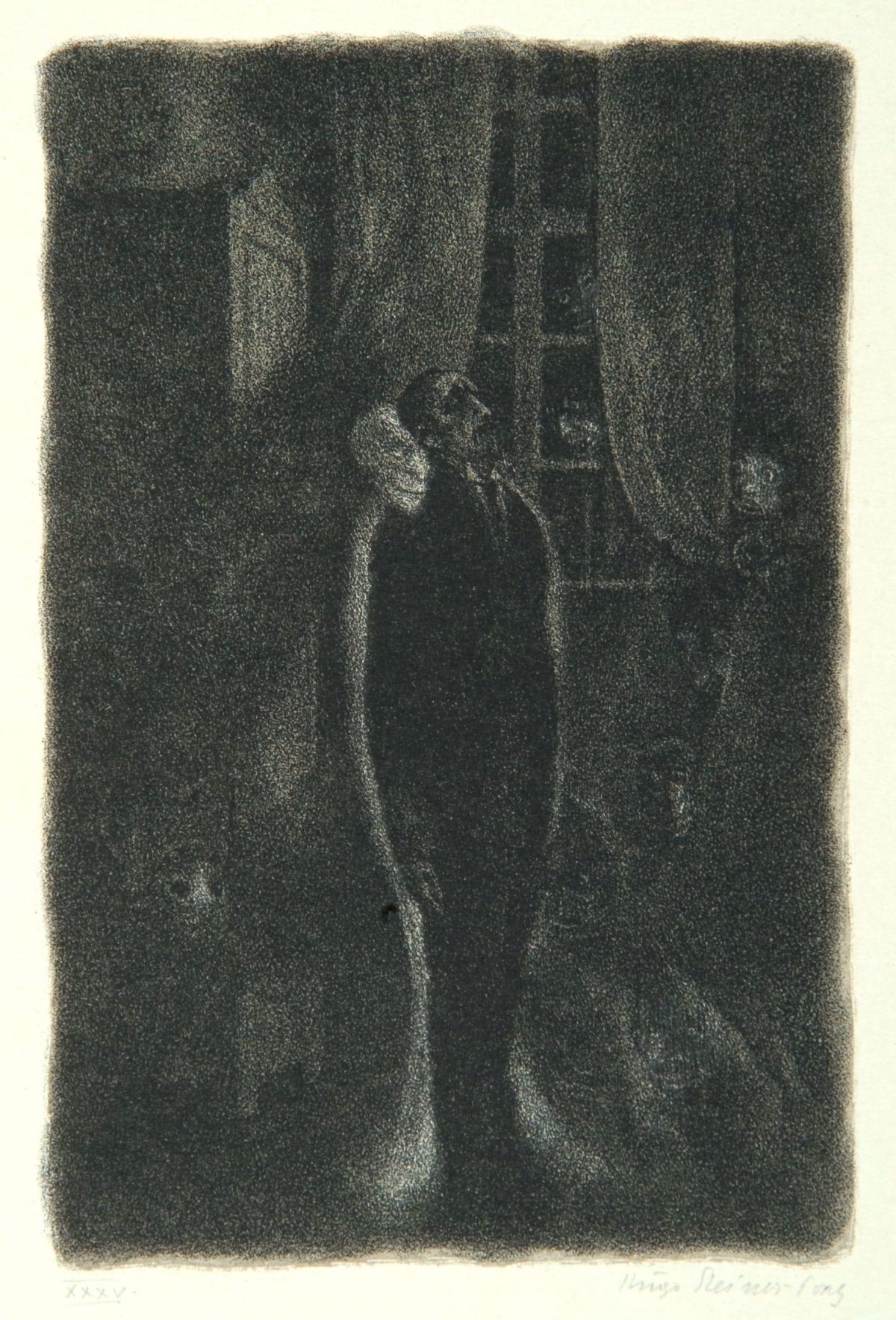

Night Ghost

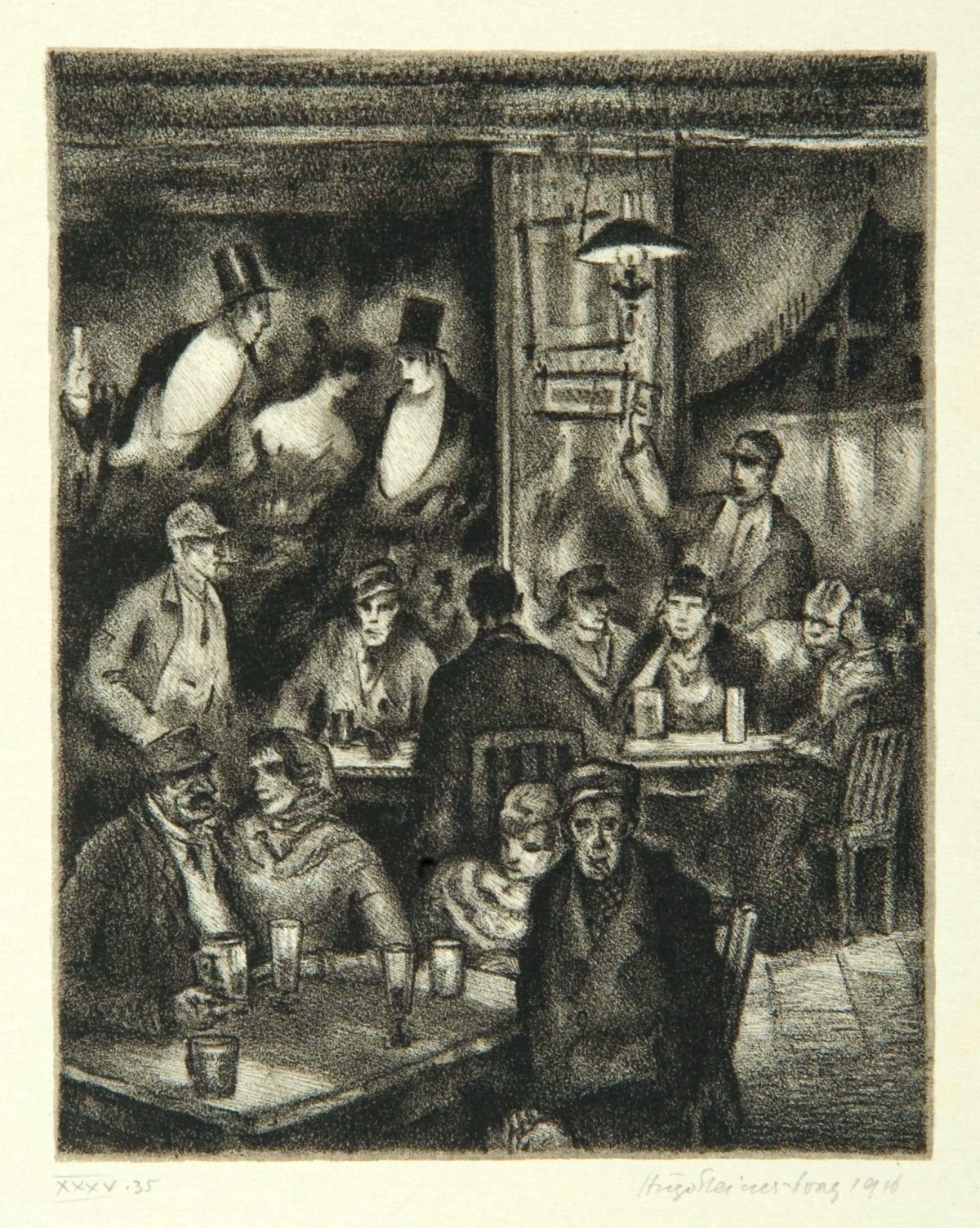

At The Loisitschek

The Stigmatized

Fear

Schemjah Hillel

The Wax Doll

In The Cathedral

The Alchemists Street

Rosina

Murder

The End of the Ghetto

The Liberated

Via: Leo Baeck Institute, Centre for Jewish Studies

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.