SCAB!

This wonderful picture is from 1916. “Don’t Be A Scab” say the two girls on rollerskates distributing leaflets in Union Square, New York.

Why scab?

The Oxford English Dictionary (via) says the word used to describe a disease for the skin from the 13th Century became an insult in the 1500s. A scab was a “mean, low, ‘scurvy’ fellow; a rascal, scoundrel”.

In the 18th Century, a scab was a worker who refused to join a union or a strike. This example is from 1777: “the Conflict would not been [sic] so sharp had not there been so many dirty Scabs; no Doubt but timely Notice will be taken of them.”

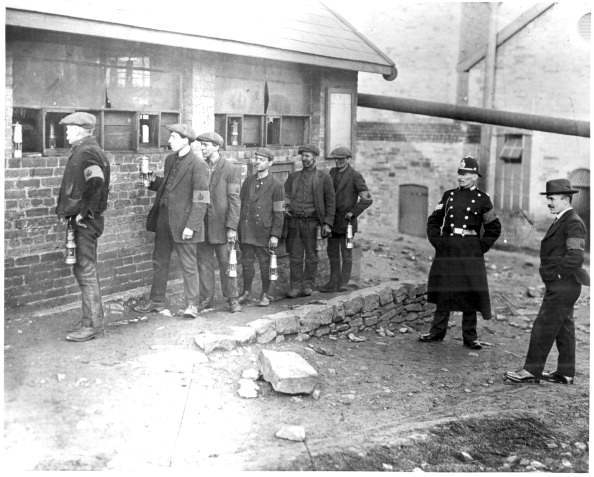

Strike breaking coal miners in the Rhondda Valley, Wales, with their lamps before going down the pit. They are wearing khaki – colored arm bands with the crown stamped on it, known as the Kakhi badge of Courage

The meaning shifted further, coming to mean a worker who breaks a strike.

In Household Words, Stephanie Smith writes:

From blemish … to strikebreaker, the history of the word scab … shows a displacement of meaning from the visceral or physical to the moral register … Just as a scab is a physical lesion, the strikebreaking scab disfigures the social body of labor—both the solidarity of workers and the dignity of work.

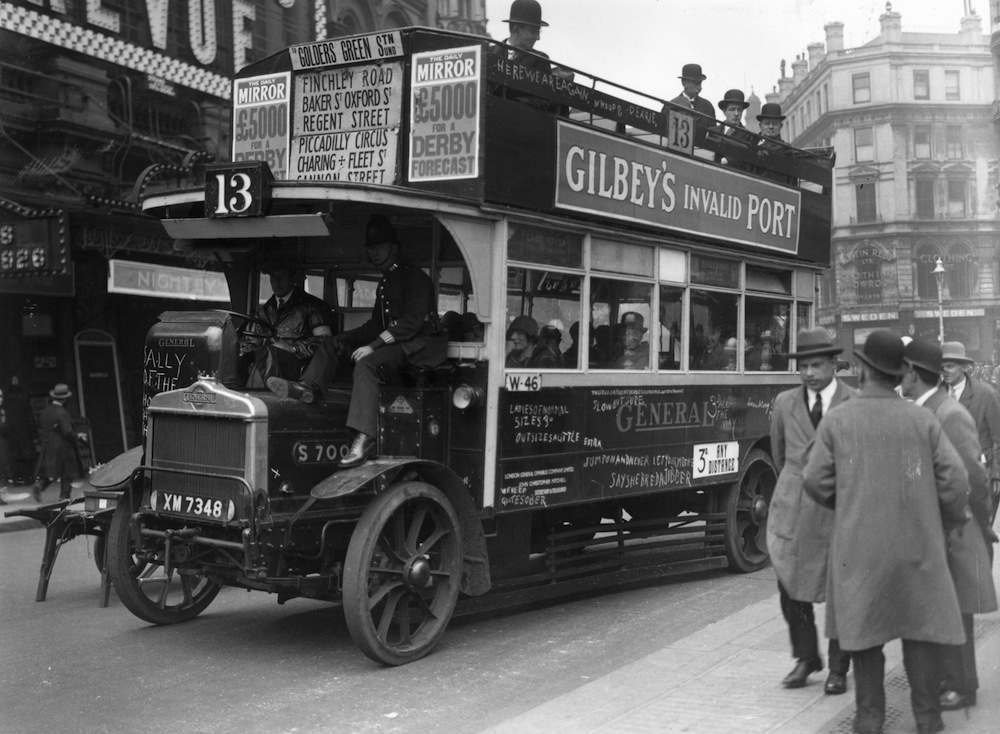

18th May 1926: An LGOC bus being driven in London by a volunteer driver with a police escort during the General Strike, May 1926. (Photo by Davis Snr/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Yasmin Nair wrote on scabs in the 21st Century:

Those who write for free or very little simply because they can afford to are scabs. This would include not just academics with tenured or tenure-track positions, but adjuncts, professionals (like paid activists and organisers), as well as, really, just about anyone who writes for places like Guernica, The Huffington Post, open Democracy.net, and The Rumpus (and this is a very, very tiny list) … My use of the word “scab” is often met with a range of responses from irritation to blind fury … But what is neoliberalism if not the rationalisation of capitalist exploitation under the rubric of “choice”? … When someone offers to write for free or a negligible amount, it allows a publication to further downgrade pay scales for working writers or to even refuse to pay them at all… The system of free writing has created a caste system, with those who can afford to work for free doing so while those who can’t struggling to pay the bills and often giving up.

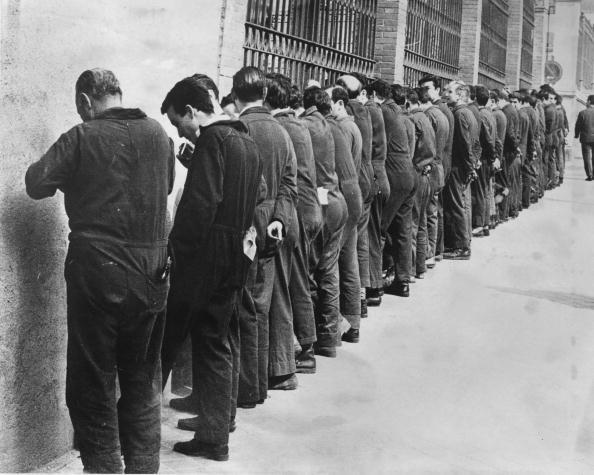

Factory workers in Spain, where striking is forbidden by law, protest by spending their lunch break standing facing the factory wall. 1968

But for the rest of this article, we’ll listen to Jack London, who had lots to say, writing in 1904:

In a competitive society, where men struggle with one another for food and shelter, what is more natural than that generosity, when it diminishes the food and shelter of men other than he who is generous, should be held an accursed thing? Wise old saws to the contrary, he who takes from a man’s purse takes from his existence. To strike at a man’s food and shelter is to strike at his life, and in a society organized on a tooth-and-nail basis, such an act, performed though it may be under the guise of generosity, is none the less menacing and terrible.

It is for this reason that a laborer is so fiercely hostile to another laborer who offers to work for less pay or longer hours. To hold his place (which is to live), he must offset this offer by another equally liberal, which is equivalent to giving away somewhat from the food and shelter he enjoys. To sell his day’s work for two dollars instead of two dollars and a half means that he, his wife, and his children will not have so good a roof over their heads, such warm clothes on their backs, such substantial food in their stomachs. Meat will be bought less frequently, and it will be tougher and less nutritious; stout new shoes will go less often on the children’s feet; and disease and death will be more imminent in a cheaper house and neighborhood.

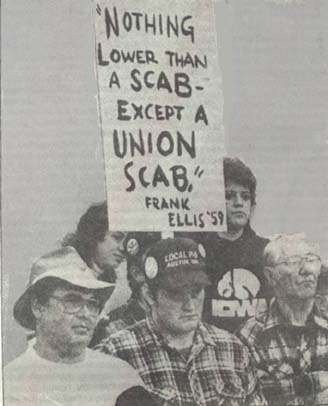

Fuck off scabs we will kill you

Dinnington Pit, England 1986 Via

Thus, the generous laborer, giving more of a day’s work for less return (measured in terms of food and shelter), threatens the life of his less generous brother laborer, and, at the best, if he does not destroy that life, he diminishes it. Whereupon the less generous laborer looks upon him as an enemy, and, as men are inclined to do in a tooth-and-nail society, he tries to kill the man who is trying to kill him.

Striking miners at the river Ruhr: Strikers reading an enactment by the district president at the gate of the coal-mine that permits police the early use of firearms – March 1912 (Photo by Berliner Illustrations Gesellschaft/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

When a striker kills with a brick the man who has taken his place, he has no sense of wrong-doing. In the deepest holds of his being, though he does not reason the impulse, he has an ethical sanction. He feels dimly that he has justification, just as the home-defending Boer felt, though more sharply, with each bullet he fired at the invading English. Behind every brick thrown by a striker is the selfish “will to live” of himself and the slightly altruistic will to live of his family. The family-group came into the world before the state-group, and society being still on the primitive basis of tooth and nail, the will to live of the state is not so compelling to the striker as the will to live of his family and himself.

13th January 1936: Portrait of the voluntary driver, Mr Burnett, on the Kettering to Rushden route, protected from attack by netting around his driving cabin. He replaces striking United Counties busmen in Northamptonshire. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

In addition to the use of bricks, clubs, and bullets, the selfish laborer finds it necessary to express his feelings in speech. Just as the peaceful country-dweller calls the sea-rover a “pirate,” and the stout burgher calls the man who breaks into his strong-box a “robber,” so the selfish laborer applies the opprobrious epithet “scab” to the laborer who takes from him food and shelter by being more generous in the disposal of his labor-power. The sentimental connotation of scab is as terrific as that of ” traitor” or “Judas,” and a sentimental definition would be as deep and varied as the human heart. It is far easier to arrive at what may be called a technical definition, worded in commercial terms, as, for instance, that a scab is one who gives more value for the same price than another.

The laborer who gives more time, or strength, or skill, for the same wage, than another, or equal time, or strength, or skill, for a less wage, is a scab. This generousness on his part is hurtful to his fellow laborers, for it compels them to an equal generousness which is not to their liking, and which gives them less of food and shelter. But a word may be said for the scab. Just as his act makes his rivals compulsorily generous, so do they, by fortune of birth and training, make compulsory his act of generousness. He does not scab because he wants to scab. No whim of the spirit, no burgeoning of the heart, leads him to give more of his labor-power than they for a certain sum.

19th May 1960: Japanese coal miners, wearing protective clothing, form a human barricade to prevent strikebreakers from entering the Mitsui Miike mine at Kumamoto. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

It is because he cannot get work on the same terms as they that he is a scab. There is less work than there are men to do work. This is patent, else the scab would not loom so large on the labor-market horizon. Because they are stronger than he, or more skilled, or more fortunate, or more energetic, it is impossible for him to take their places at the same wage. To take their places he must give more value, must work longer hours, or receive a smaller wage. He does so, and he cannot help it, for his will to live is driving him on as well as they are being driven on by theirs, and to live he must win food and shelter, which he can do only by receiving permission to work from some man who owns a bit of land or piece of machinery. And to receive permission from this man, he must make the transaction profitable for him.

Chrysler strikers warn away scab workers. Courtesy of King’s Academy. via

Viewed in this light, the scab who gives more labor-power for a certain price than his fellows is not so generous after all. He is no more generous with his energy than the chattel slave and the convict laborer, who, by the way, are the almost perfect scabs. They give their labor-power for about the minimum possible price. But, within limits, they may loaf and malinger, and, as scabs, are exceeded by the machine, which never loafs and malingers, and which is the ideally perfect scab.

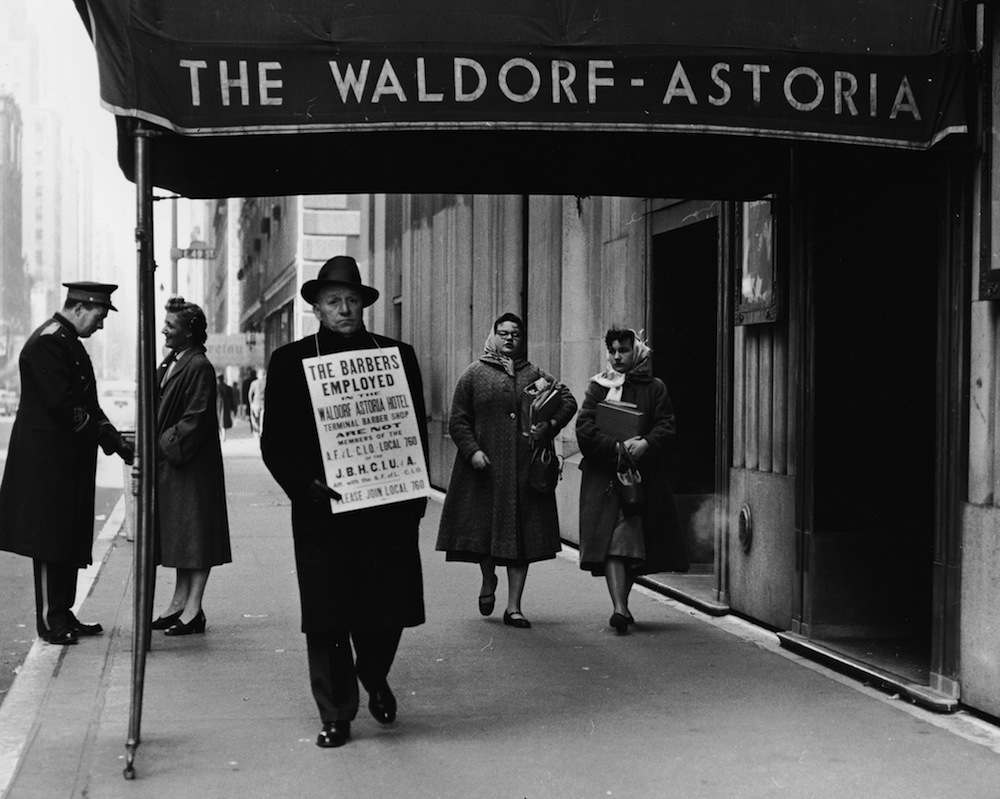

A lone hotel barber, a member of the AFL-CIO, carries a sign objecting to scab employees as he strikes outside the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York City, 1940s. A uniformed doorman speaks to a woman in the background. (Photo by Corry/Getty Images)

It is not nice to be a scab. Not only is it not in good social taste and comradeship, but, from the standpoint of food and shelter, it is bad business policy. Nobody desires to scab, to give most for least. The ambition of every individual is quite the opposite,—to give least for most; and as a result, living in a tooth-and-nail society, battle royal is waged by the ambitious individuals. But in its most salient aspect, that of the struggle over the division of a joint-product, it is no longer a battle between individuals, but between groups of individuals. Capital and labor apply themselves to raw material, make something useful out of it, add to its value, and then proceed to quarrel over the division of the added value. Neither cares to give most for least. Each is intent on giving less than the other and on receiving more.

…

January 1972: A picket from Warwickshire questions a lorry driver leaving West Drayton National Coal Board Depot at the height of the miners’ strike. (Photo by Evening Standard/Getty Images)

In the group-struggle over the division of the joint-product, labor utilizes the union with its two great weapons,—the strike and boycott; while capital utilizes the trust and the association, the weapons of which are the blacklist, the lockout, and the scab. The scab is by far the most formidable weapon of the three. He is the man who breaks strikes and causes all the trouble. Without him there would be no trouble, for the strikers are willing to remain out peacefully and indefinitely so long as other men are not in their places, and so long as the particular aggregation of capital with which they are fighting is eating its head off in enforced idleness.

Middle class volunteers to provide basic services during the The UK General Strike lasted nine days (May 3 to 12, 1926). The strike resulted in defeat for the unions. A long confrontation in the coal industry, with strikes and lockouts, had made no progress. To support the 800,000 striking miners the unions called out 1,750,000 workers. The government was well prepared.

But both warring groups have reserve weapons up their sleeves. Were it not for the scab, these weapons would not be brought into play. But the scab takes the places of the strikers, who begin at once to wield a most powerful weapon,—terrorism. The will to live of the scab recoils from the menace of broken bones and violent death. With all due respect to the labor leaders, who are not to be blamed for volubly asseverating otherwise, terrorism is a well-defined and eminently successful policy of the labor unions. It has probably won them more strikes than all the rest of the weapons in their arsenal. This terrorism, however, must be clearly understood. It is directed solely against the scab, placing him in such fear for life and limb as to drive him out of the contest. But when terrorism gets out of hand and inoffensive non-combatants are injured, law and order threatened, and property destroyed, it becomes an edged tool that cuts both ways. This sort of terrorism is sincerely deplored by the labor leaders, for it has probably lost them as many strikes as have been lost by any other single cause.

…

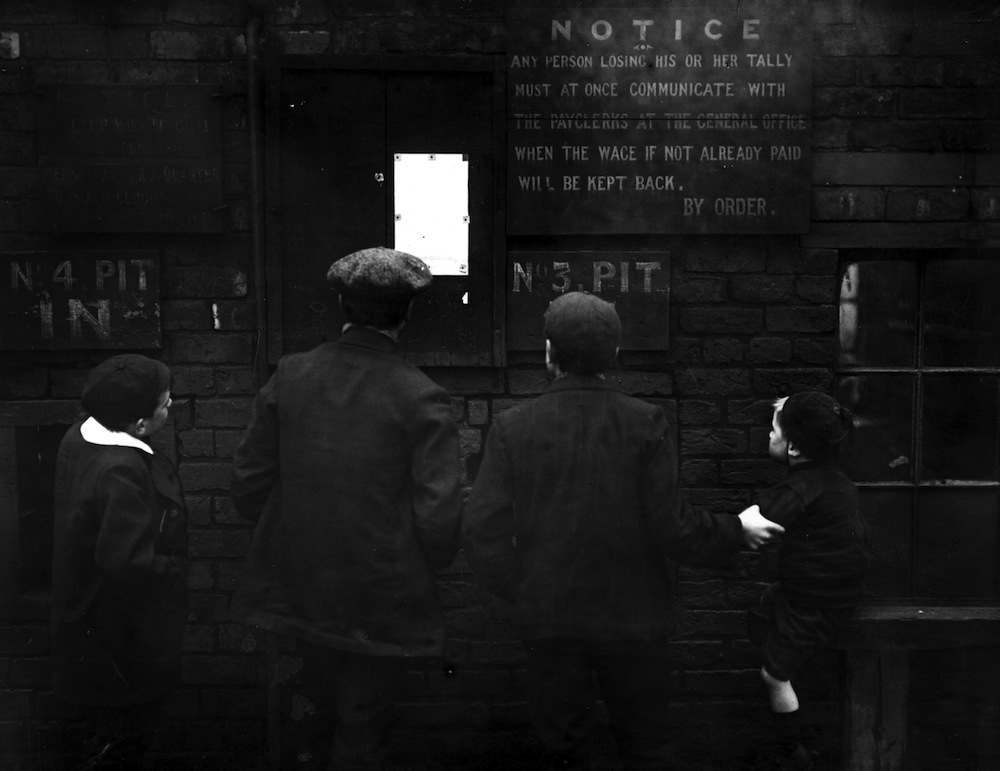

February 1912: Young miners and their brothers read a notice outside a mine in Wigan during the miners’ strike. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

This struggle not to be a scab, to avoid giving more for less, and to succeed in giving less for more, is more vital than it would appear on the surface. The capitalist and labor groups are locked together in desperate battle, and neither side is swayed by moral considerations more than skin-deep. The labor-group hires business agents, lawyers, and organizers; and is beginning to intimidate legislators by the strength of its solid vote, and more directly, in the near future, it will attempt to control legislation by capturing it bodily through the ballot-box. On the other hand, the capitalist-group, numerically weaker, hires newspapers, universities, and legislatures, and strives to bend to its need all the forces which go to mould public opinion.

October 1948: In the St Etienne region miners at a barricaded door to prevent security troops from approaching coal-pits. About 100 aeroplane-loads of troops from North Africa have been flown in to supplement the 10,000 soldiers already guarding pits against Communist saboteurs. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

The only honest morality displayed by either side is white-hot indignation at the iniquities of the other side. The striking teamster complacently takes a scab driver into an alley and with an iron bar breaks his arms so that he can drive no more, but cries out to high heaven for justice when the capitalist breaks his skull by means of a club in the hands of a policeman. Nay, the members of a union will declaim in impassioned rhetoric for the God-given right of an eight-hour day, and at the time be working their own business agent seventeen hours out of the twenty-four.

…

When a publisher offers an author better royalties than other publishers have been paying him, he is scabbing on those other publishers. The reporter on a newspaper who feels he should be receiving a larger salary for his work, says so, and is shown the door, is replaced by a reporter who is a scab; whereupon, when the belly-need presses, the displaced reporter goes to another paper and scabs himself. The minister who hardens his heart to a call, and waits for a certain congregation to offer him say five hundred a year more, often finds himself scabbed upon by another and more impecunious minister; and the next time it is his turn to Scab while a brother minister is hardening his heart to a call. The scab is everywhere. The professional strike-breakers, who, as a class, receive large wages, will scab on one another, while scab unions are even formed to prevent scabbing upon scabs.

The 1980 via

There are non-scabs, but they are usually born so, and are protected by the whole might of society in the possession of their food and shelter. King Edward is such a type, as are all individuals who receive hereditary food-and-shelter privileges, such as the present Duke of Bedford, for instance, who yearly receives $75,000 from the good people of London because some former king gave some former ancestor of his the market privileges of Covent Garden. The irresponsible rich are likewise non-scabs, and, by them is meant that coupon-clipping class which hires its managers and brains to invest the money usually left it by its ancestors.

1935: A scene depicting unionized strikers fighting with a group of ‘scabs’ or nonunion replacement employees as they try to cross the picket line at a factory. One of the strikers’ signs reads ‘We fight fascism.’ Several men lay unconscious on the ground.

Outside these lucky creatures, all the rest, at one time or another in their lives, are scabs, at one time or another are engaged in giving more for a certain price than any one else.

Members of a miners’ picket at Tilmanstone Colliery, Kent, try to persuade a colleague not to cross the picket line, in the last days of the miners’ strike, March 1985. The miners of Tilmanstone were one of the last groups to return to work after the strike. (Photo by Steve Eason/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

…

Such is the tangle of conflicting interests in a tooth-and-nail society that people cannot avoid being scabs, are often made so against their desires, and unconsciously. When several trades in a curtain locality demand and receive an advance in wages, they are unwittingly making scabs of their fellow laborers in that district who have received no advance in wages.

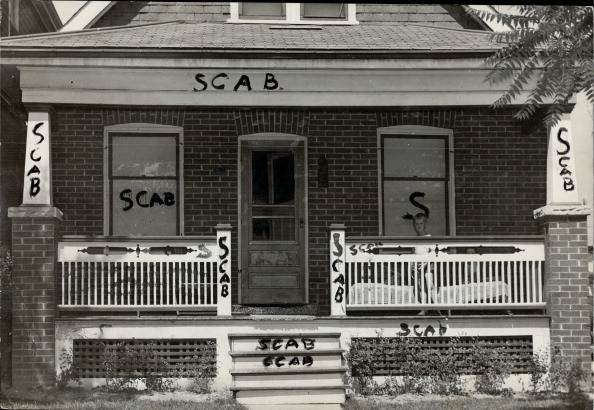

JULY 19: 1946: Strikebreaker’s house is shown smeared with the painted word scab. M Lawrence; when notified ot the incident; deplored such action but said it could h work of stooges.

…

The English laborer is starving to-day because, among other things, he is not a scab. He practices the policy of “Ca’ Canny,” which may be defined as “go easy.” In order to get most for least, in many trades he performs but from one fourth to one sixth of the labor he is well able to perform. An instance of this is found in the building of the Westinghouse Electric Works at Manchester. The British limit per man was 400 bricks per day. The Westinghouse Company imported a “driving” American contractor aided by half-a-dozen “driving” American foremen, and the British bricklayer swiftly attained an average of 1800 bricks per day, with a maximum of 2500 bricks for the plainest work.

Striking auto workers beat a worker as he tries to cross the picket line during a 1941 strike at the Ford Rouge Plant, in Dearborn, Michigan. Via

But the British laborer’s policy of Ca’ Canny, which is the very honorable one of giving least for most, and which is likewise the policy of the English capitalist, is nevertheless frowned upon by the English capitalist whose business existence is threatened by the great American Scab…

Yet Ca’ Canny is a disastrous thing to the British laborer. It has driven ship-building from England to Scotland, bottle-making from Scotland to Belgium, flint-glass-making from England to Germany, and to-day it is steadily driving industry after industry to other countries. A correspondent from Northampton wrote not long ago: “Factories are working half and third time…. There is no strike, there is no real labor trouble, but the masters and men are alike suffering from sheer lack of employment. Markets which were once theirs are now American.” It would seem that the unfortunate British laborer is ‘twixt the devil and the deep sea. If he gives most for least, he faces a frightful slavery such as marked the beginning of the factory system. If he gives least for most, he drives industry away to other countries, and has no work at all.

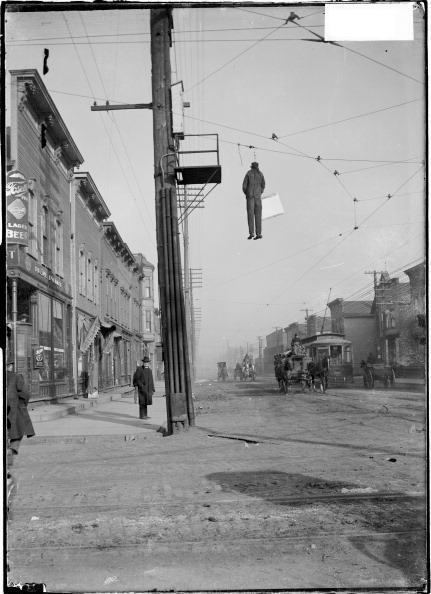

Effigy of Frank Curry, strike-breaker, hanging over 42nd Street and Wentworth Avenue during the Chicago City Railway Strike, Chicago, Illinois, November 19, 1903.

…

And as long as men continue to live in this competitive society, struggling tooth and nail with one another for food and shelter, (which is to struggle tooth and nail with one another for life), that long will the scab continue to exist. His will to live will force him to exist. He may be flouted and jeered by his brothers, he may be beaten with bricks and clubs by the men who by superior strength and capacity scab upon him as he scabs upon them by longer hours and smaller wages, but through it all he will persist, going them one better, and giving a bit more of most for least than they are giving.

Story via: The Atlantic

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.

![1916, "Don't Be A Scab" [640x463] Two girls on rollerskates distribute leaflets in Union Square.](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/strike.jpg)