Repetition, Repetition, Repetition

Oh mental hospitals

Oh mental hospitals

They put electrodes in your brain

And you’re never the same

You don’t dig repetition—The Fall, “Repetition”

Mental hospitals have long been horror movie tropes, reflecting the profound stigma surrounding mental illness. The fear of schizophrenia, depression, and the irrational mind is a remnant of Medieval European thinking, argued French theorist Michel Foucault in Madness and Civilization, a leftover from the treatment of lepers. Asylums rose up to house the socially unwanted—the impoverished, the ill, the unwed mothers—who were slotted into an already existing system built to contain outsiders.

Leprosy disappeared, the leper vanished, or almost, from memory; these structures remained. Often in these same places, the formulas of exclusion would be repeated, strangely similar two or three centuries later. Poor vagabonds, criminals, and “deranged minds” would take the part played by the leper, and we shall see what salvation was expected from this exclusion for them and for those who excluded them as well.

Such institutions were common to industrial Britain and to all working-class narratives of the Industrial Age, from Charles Dickens to Ken Loach, with workhouses, prisons, and madhouses walling off the undesirables while promising reform. Prestwich Asylum is one such place whose history represents how people diagnosed with “melancholia”—sometimes caused, in several early male patients at least, by “trouble at work” or “money troubles”—were shunted away into what were essentially workhouses with several tortuous forms of medically unsound treatment.

Opened in 1851, Prestwich “had become one of the largest of its kind in Europe by 1900,” notes Manchester Central Library’s Archive Plus. “It was extended in order to increase the capacity: ‘The Annex’ created space for an extra 1,100 patients, meaning that by 1903 around 3,135 patients could be housed there. Eventually the asylum closed in the 1990s having run for over 150 years.” Conditions improved considerably, but the social stigma and shame remained.

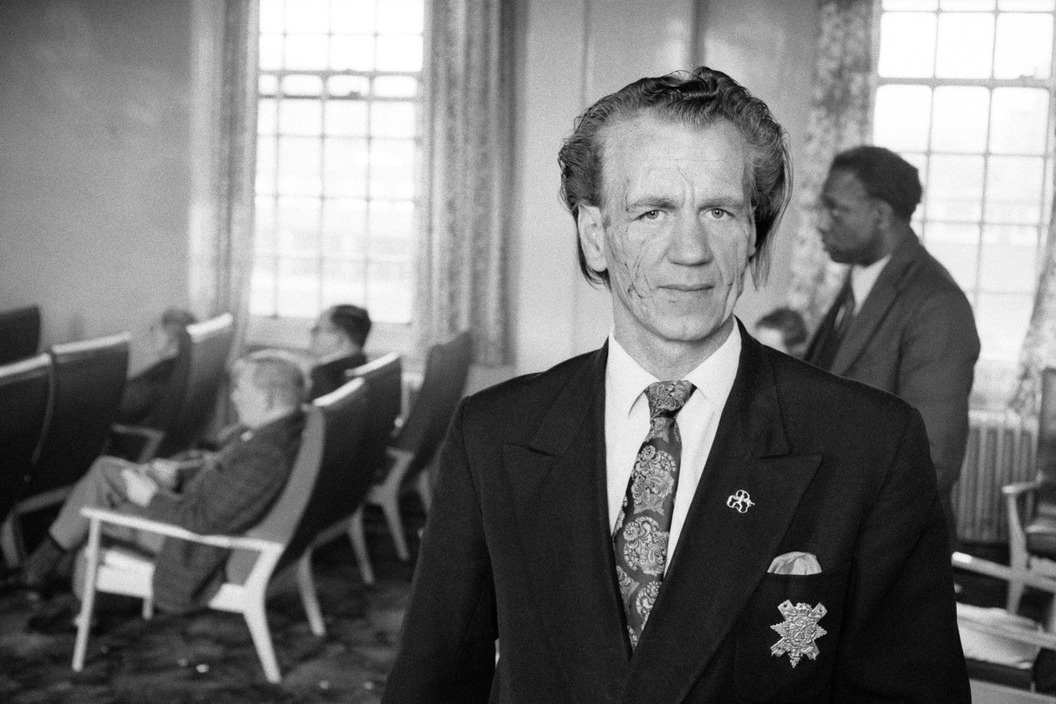

“The Lunatic Asylums like Prestwich grew up in the same period as the industries,” writes Manchester academic Janet Batsleer, “and, like the industries, they closed.” Batsleer first visited Prestwich, where her mother was a patient, in 1972, the year Martin Parr began his first visual essay series at the hospital as a young photography student at Manchester Polytechnic. These are portraits, Batsleer writes, “of the lives of working-class people, who no longer had any recourse to family support and had to face the shame associated with places like this. The Workhouse. The Lunatic Asylum.”

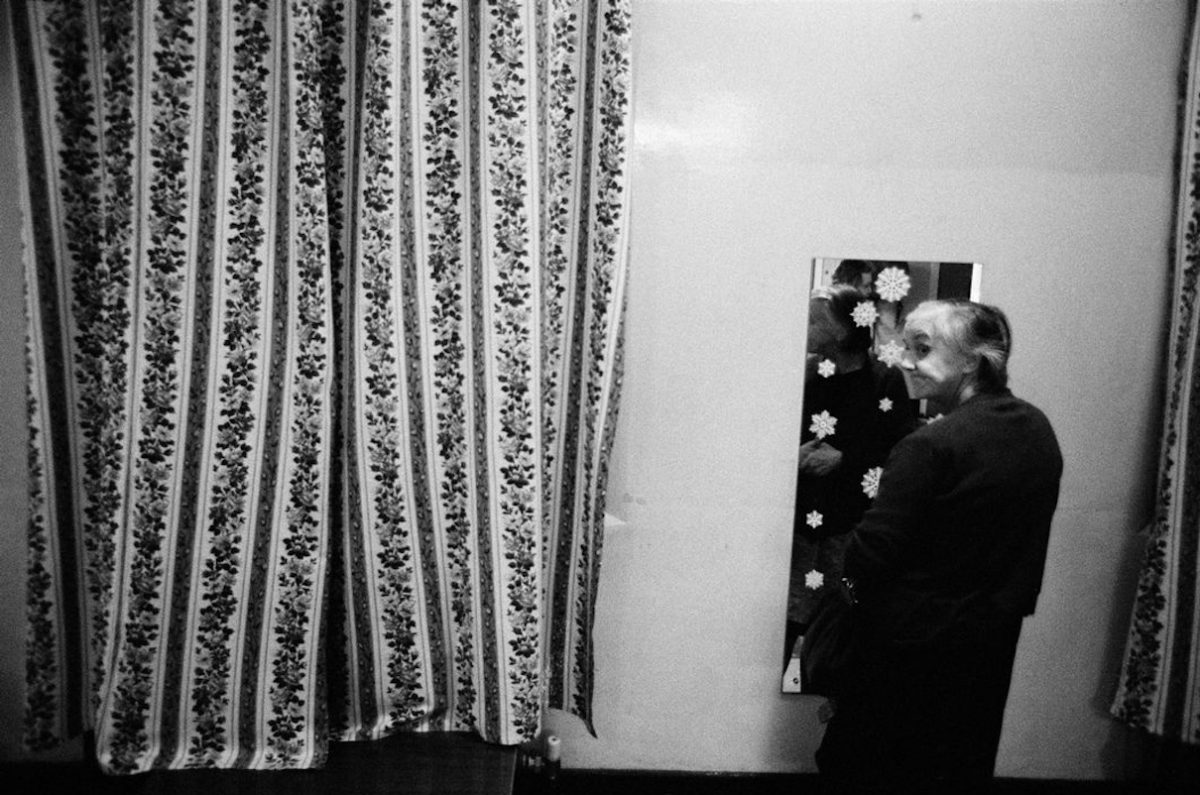

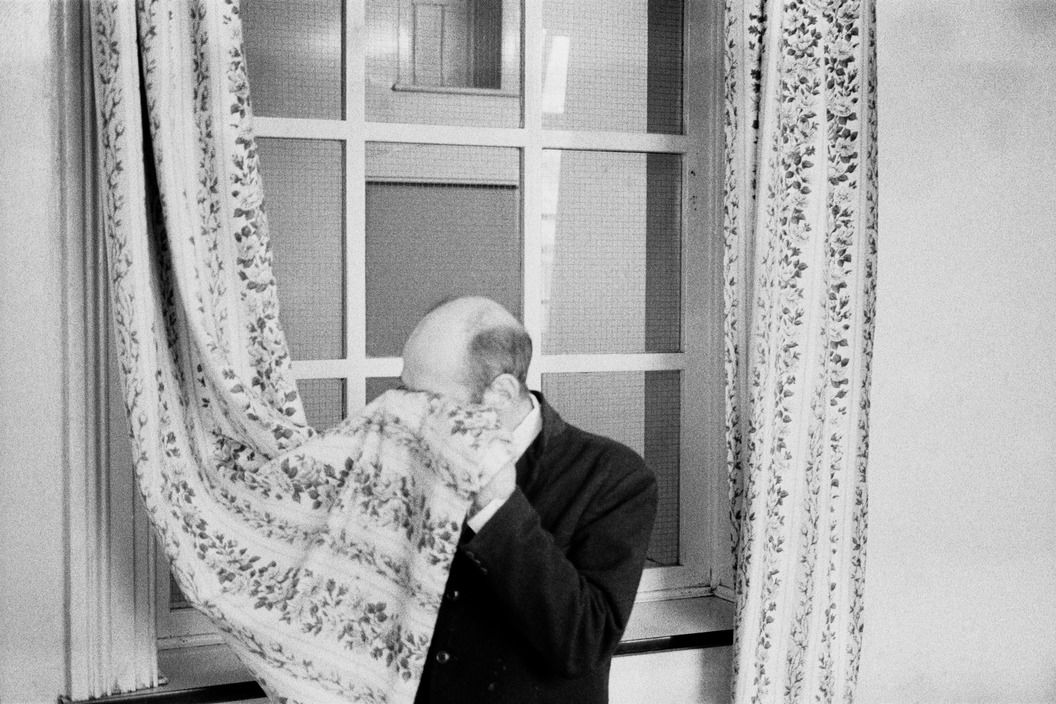

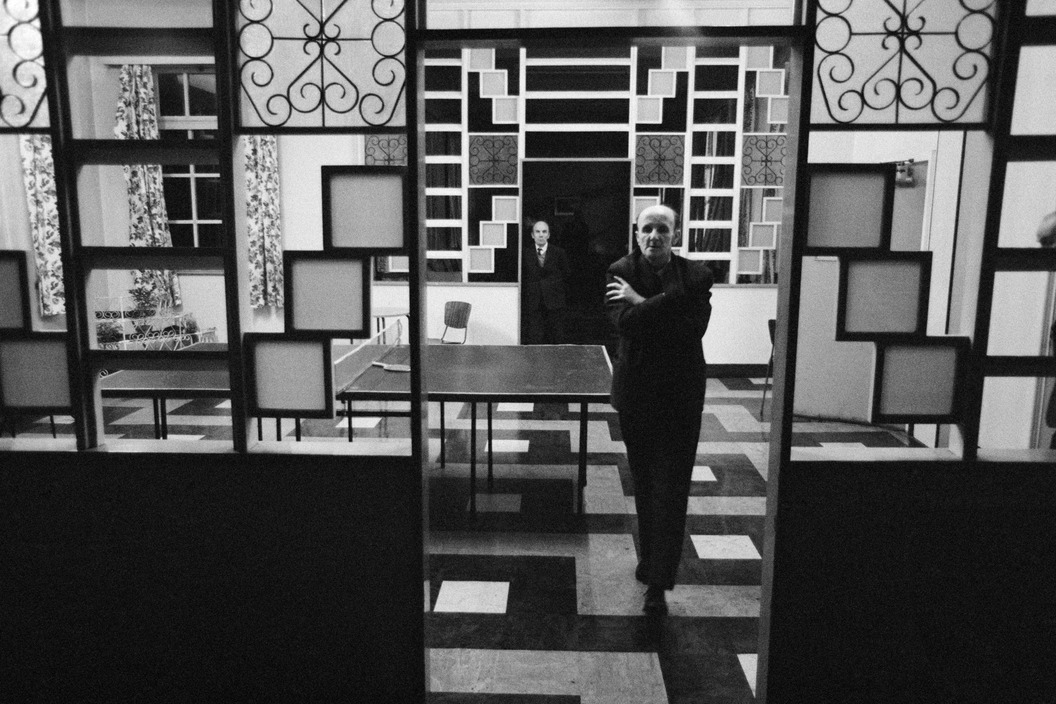

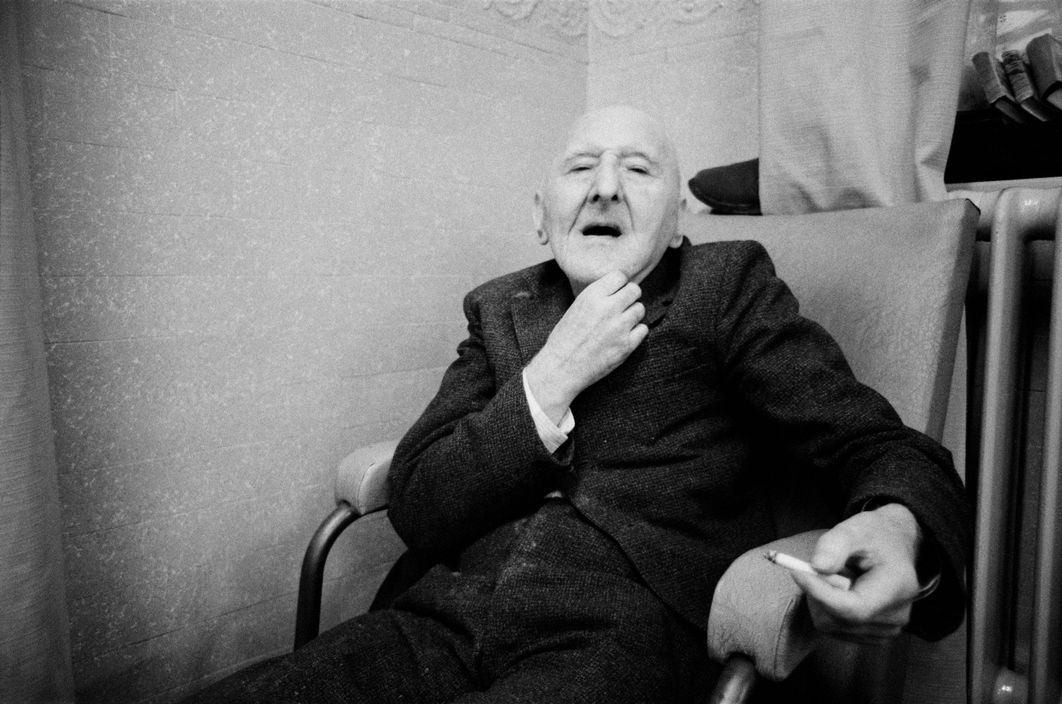

The stigma extended to those outside Prestwich as well: “A failure to care and a handing over of a family member to such a place was experienced as a shameful event.” Parr’s photographs humanize their subjects but also contain “a certain deliberate lack of empathy. These are not sentimental working-class family snapshots.” They do not normalize the space of the mental hospital. They capture “moments and souls that would otherwise have passed from the record,” writes Desmond Bullen at Northern Soul, “with no more trace than the nicotine that discoloured the ceilings of the one-time county asylum.”

Prestwich has become known as both the onetime home of the sprawling asylum and the onetime home of The Fall frontman Mark E. Smith, whose face now sneers down from a chip shop in a mural painted after his death. Smith wrote about madness and asylums in many songs, but for him, the madness of Prestwich could be found outside the hospital walls. “Writing about Prestwich,” he once said, “is just as valid as Dante writing about his inferno.” The principle characteristic of industrial modernity, he wrote, from “President Carter” to “Chairman Mao,” is “repetition,” a term that sounds suspiciously like a popular definition of insanity.

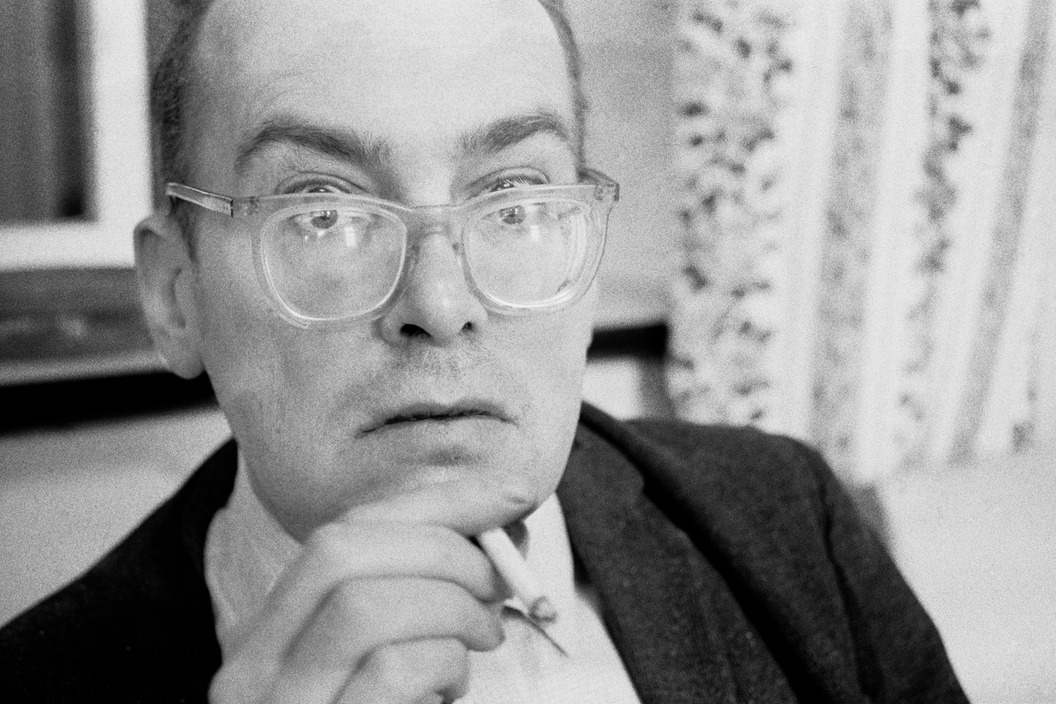

Parr’s photos show patients participating in music therapy sessions, fancy dress parties, and football matches against other hospitals: moments of levity, tedium, vulnerability, and sadness. The photographer first settled on the project when he visited a friend’s brother who had been admitted. “I was so taken with the place,” he says, “that I decided to do some work and sought out permission to photograph there, then got stuck in for the following three months, photographing constantly. Visually it was very striking. The whole atmosphere…you just knew there was scope there. When you’re a nineteen year old photographer, you have aspirations, but it’s difficult to know actually what to say. But suddenly I found something I wanted to articulate.” He doesn’t tell us what he intended to get across with his photo essay of Prestwich, but leaves it the viewer to interpret.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.