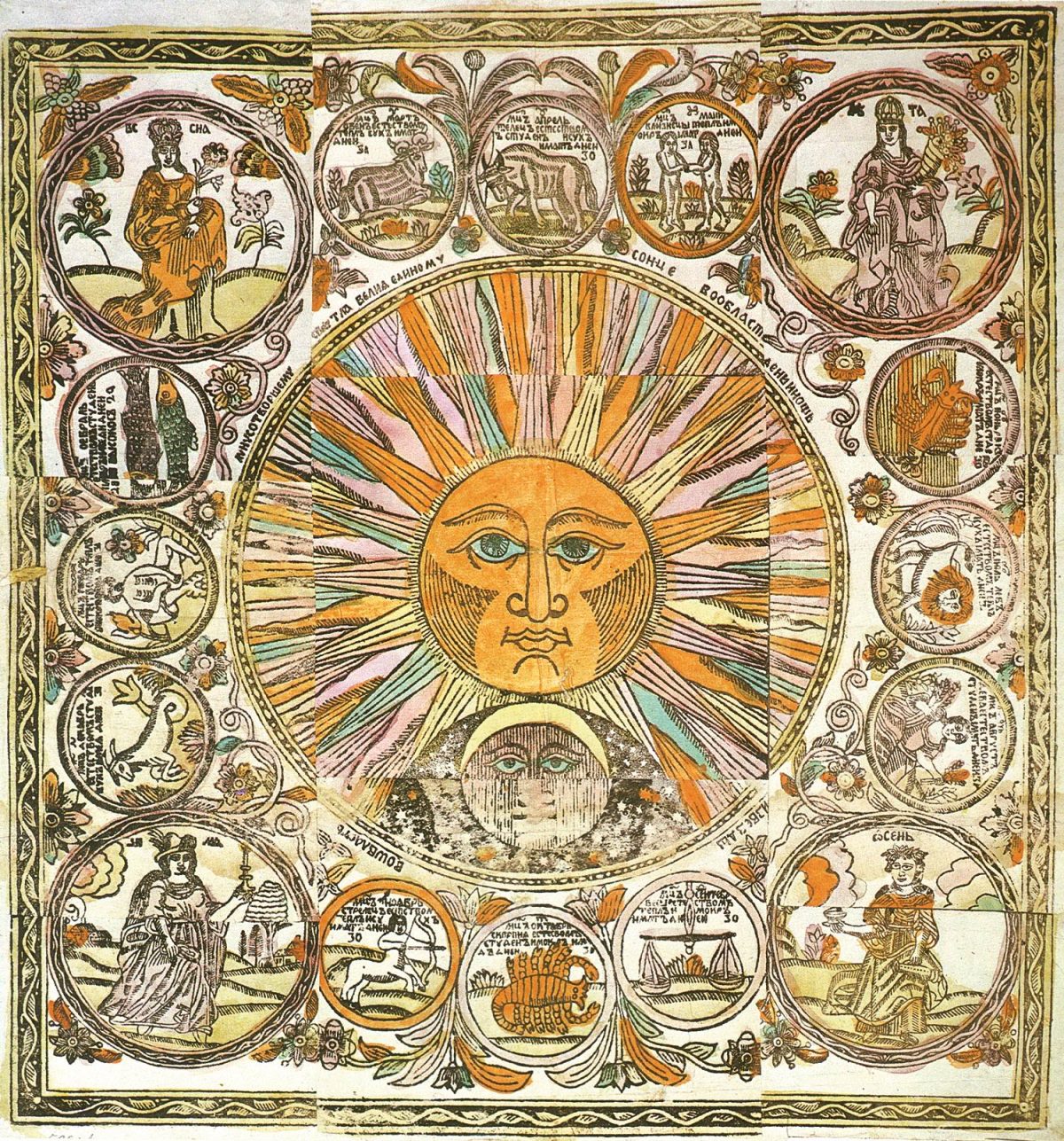

A Lubok is a Russian hand-coloured picture in the same vein as folk prints, chapbooks and broadsides such as the Calaveras created by Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913). In Russia, lubki appeared in the middle of the seventeenth century and survived until the beginning of the twentieth. First aimed at the wealthy and based on Biblical texts, thanks to cheap paper and printing, they later featured contemporary people and matters, and became a staple of the working classes.

To make a lubok, the artist created a woodcut, made prints from it and painted it by hand. The name is said to come from the word luba, meaning the inner part of linden bark, which was used for the woodcut.

“The word lubki was also connected with Lubianka Street, the street of the printers in old Moscow,” notes Adela Roatcap. “Lubianka Street, and its infamous prison, were named after lubki.”

The earliest surviving lubki were printed near Kiev in 1625. They were commissioned by the Russian Orthodox clergy of the Monastery of the Caves near Kiev. Lubki depicting Russian saints, their miracles and teachings were useful in feuds with their Polish, Roman Catholic neighbours.

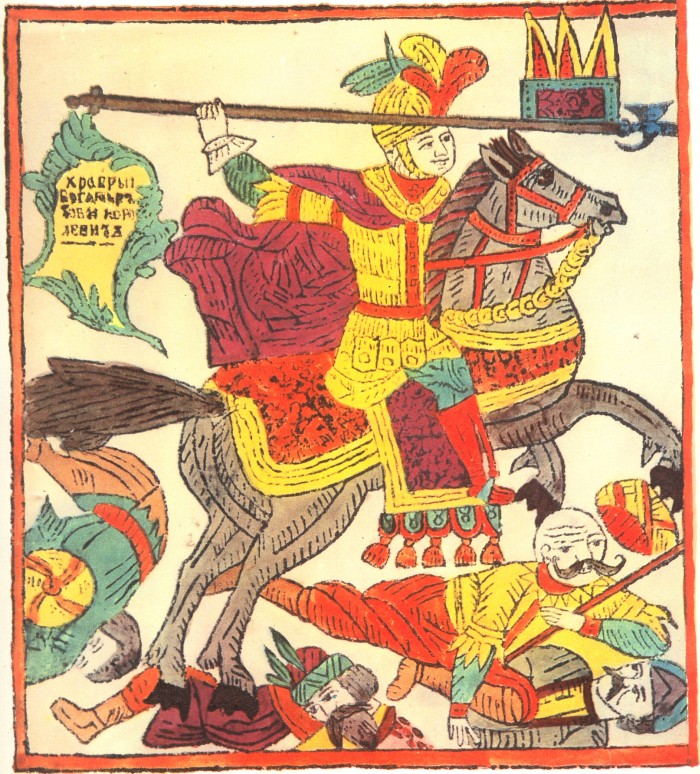

The Valiant Knight Yeruslan Rescuing Princess Anastasia, an 18th-century lubok.

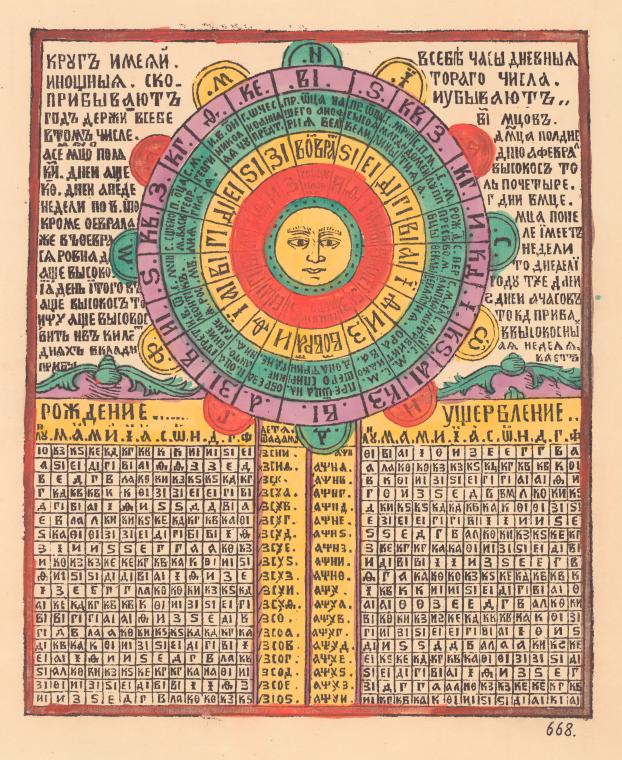

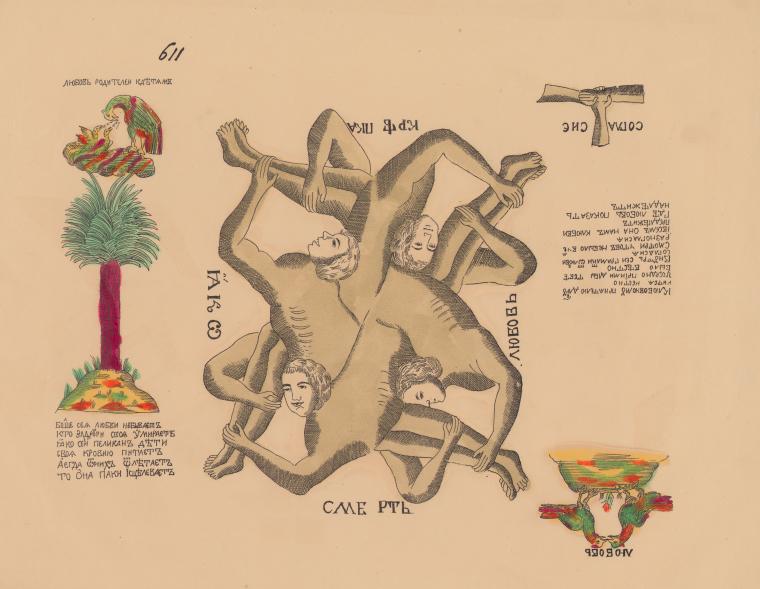

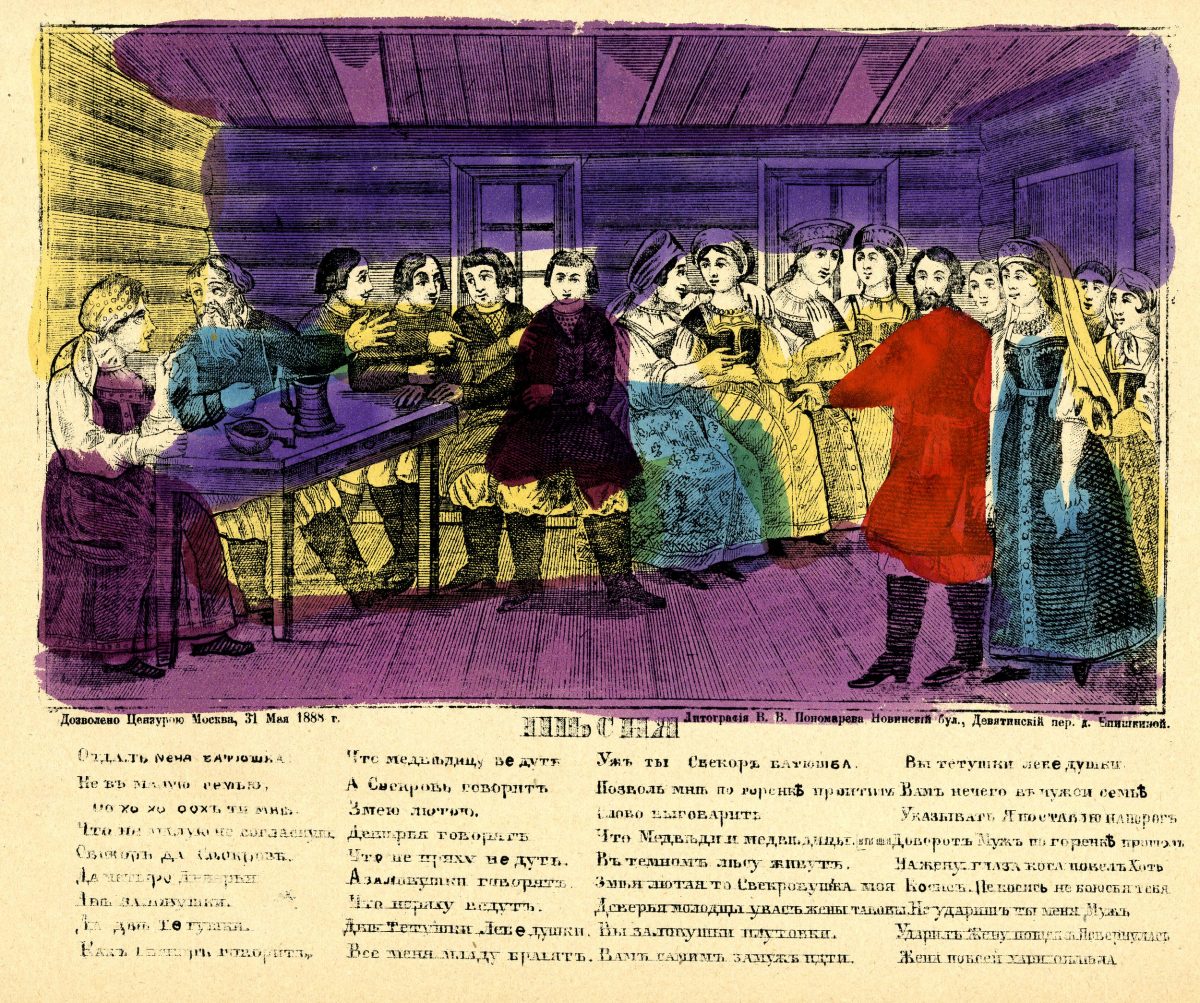

These popular prints, bright pictures of religious and secular subjects with explanatory captions, were widely used for the decoration of homes and taverns. The majority of them are now lost. But collections do exist.

The New York Public Library has a collection by Muscovite Dimitrii Aleksandrovich Rovinskii (via PDR), a high-ranking jurist in the 19th Century, and there are a lot more at the Museum of Russian Lubok and Naive Art, which notes:

Due to the specifics of the social and economic conditions of life of the Russian state (it should not be forgotten that serfdom was abolished only in 1861), the folk picture continued to exist in Russia much longer than in other European countries. And, having no equal in terms of its numbers and versatility, it is of great value to our culture. These printed sheets appear as evidence of the life and everyday life of the people for many centuries, serve as a kind of mirror of the Russian soul.

The subjects of many prints were drawn from literature which circulated in handwritten copies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: Velikoe Zertsalo (The Great Mirror), a collection of tales and parables; Alexandria, a history of Alexander the Great’s campaigns; and Domostroi, a manual of behaviour and household encyclopaedia. The mediaeval western legend of the enchanted Melusina found reflection in a print entitled Melusina the Fish.

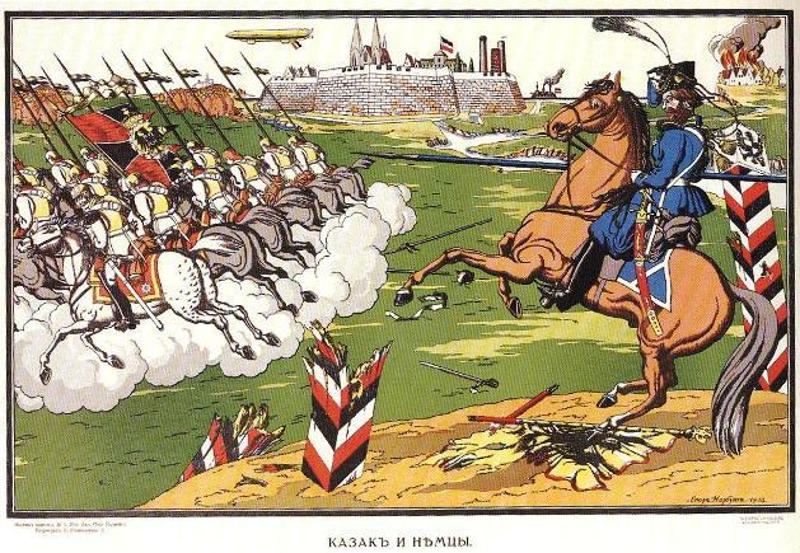

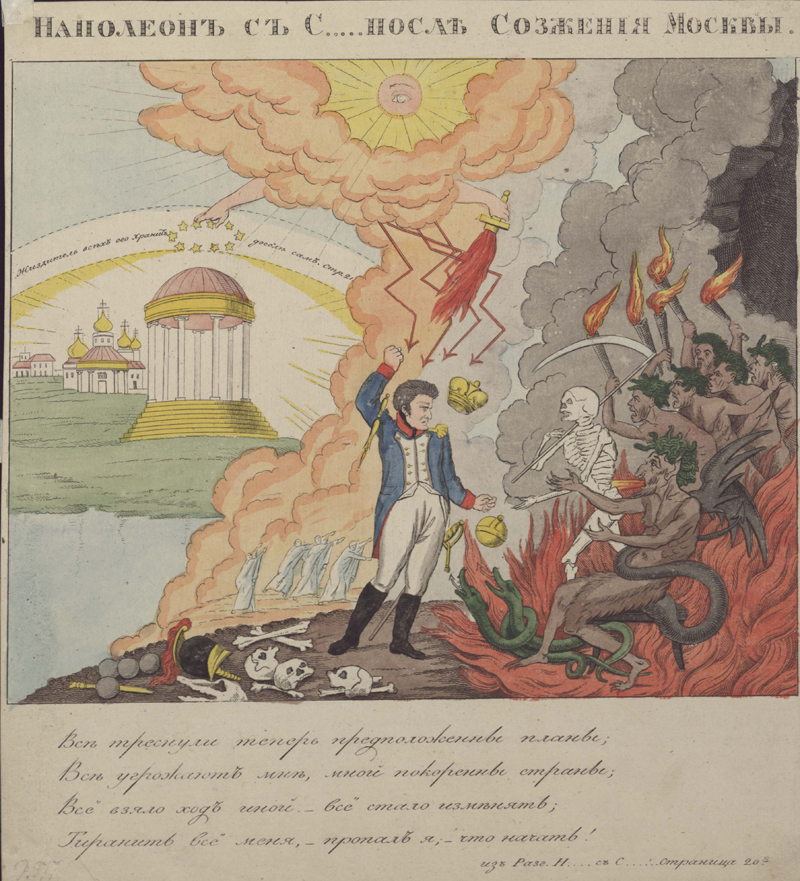

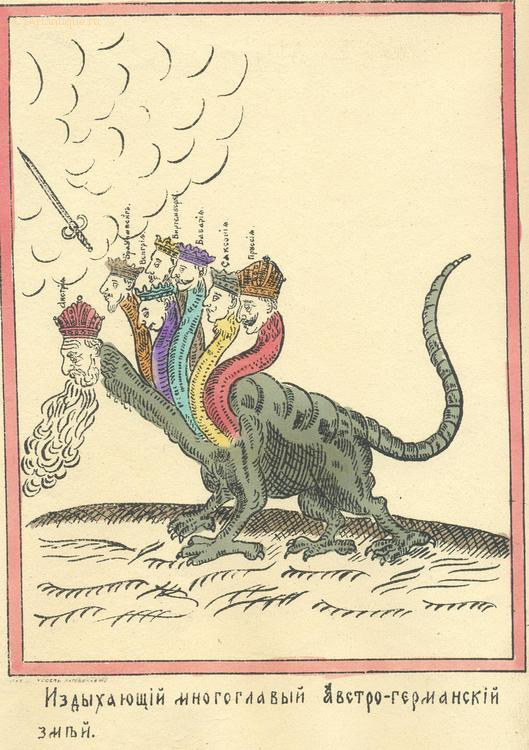

Satirical versions played a role in wartime. Napoleon and ‘inferior’ French culture were lampooned, while Russian peasants were portrayed as heroes.

Lubki also mocked Russia’s great and good, although social commentary meant that artists encountered difficulties with church and government censors.

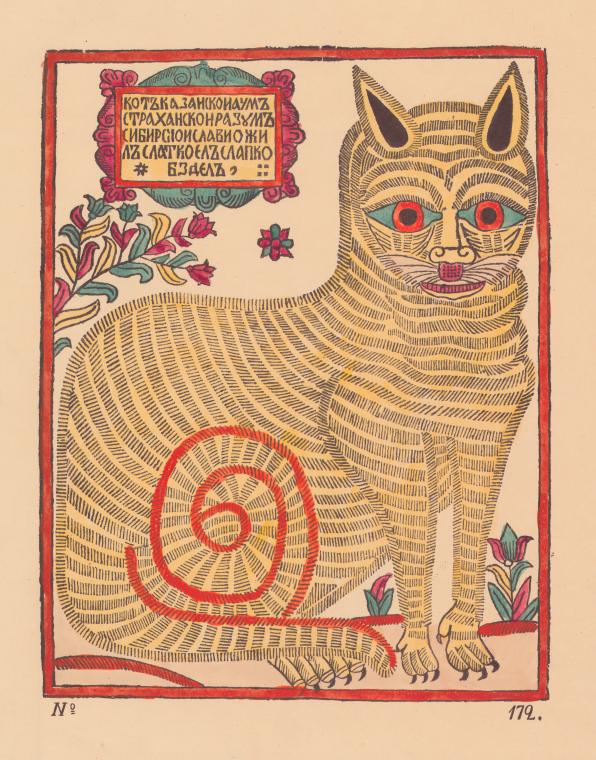

The lubok below satirises Peter the Great, depicting the tsar as a sitting cat with a neatly trimmed moustache. Above, in the frame, there is an inscription parodying the sovereign’s title:

The Cat from Kazan,

In the manner of Astrakhan,

By reason of Siberia,

Lives gloriously,

Manages agreeably,

And farts sweetly.

Between 1697-1698, Tsar Peter visited Europe in disguise to learn about shipbuilding and Western culture. Enamoured with what he saw and eager to modernise Russia so that it could compete with the European superpowers, Tsar Peter issued a ukase (edict) forcing Russian boyars to shave off their beards or pay a fine. Old Believer boyars were defiant, claiming that without a beard they could not enter Paradise. They called Peter the Anti-Christ.

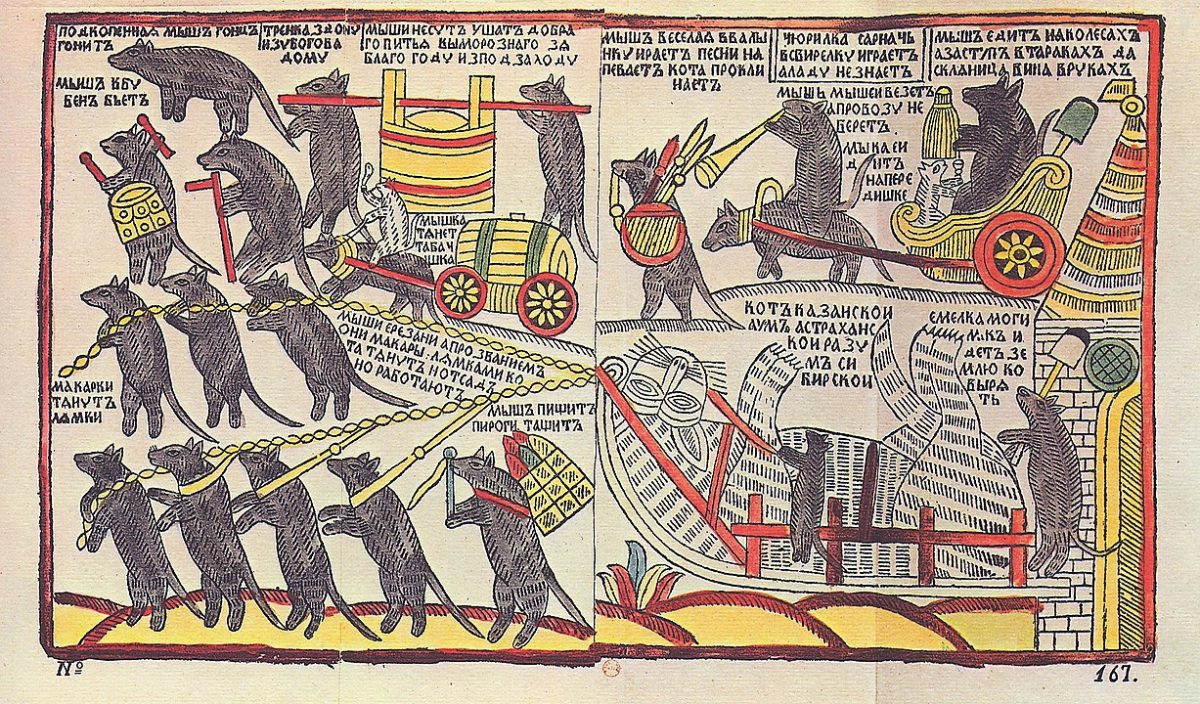

In January 1725, when Peter the Great died, the Old Believers had their vengeance. Vasili Koren was commissioned to design ‘How the Mice Buried the Cat,’ a 33 by 56cm lubok printed from two side-by-side wood blocks. The dead Cat is, of course, Tsar Peter himself as the peculiar smelling Cat of Kazan, who, as the inscription declares, may be dead but ‘still possesses the spirit of Astrakhan and the wisdom of Siberia’. Eight lively mice from the city of Riazan pull Tsar Peter’s sled through the January snow. Standing at the back of it a mouse holds a shovel aloft. On the left, a mouse beats a drum announcing the funeral cortege, while other mice carry refreshments for the wake: loaves of bread, a barrel of brandy and a tub of beer. Some mice represent territories which Peter won in his battles with Sweden. Justice is served: above the dead Tsar, a group of happy mice ride in a European cabriolet and play the sort of horns and bagpipes which Peter introduced to Russia.

![Gromadnyi kot." [Big Cat], 1881](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/lubok-7.jpg)

Gromadnyi kot – Big Cat, 1881

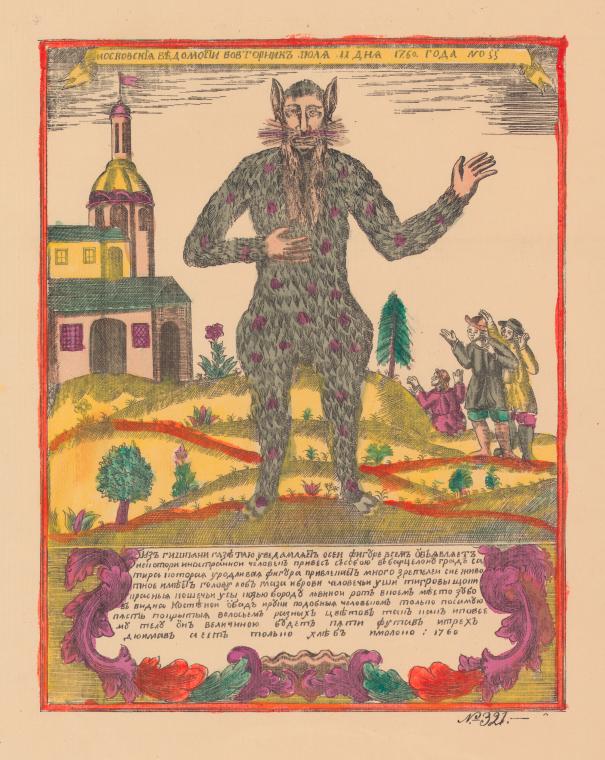

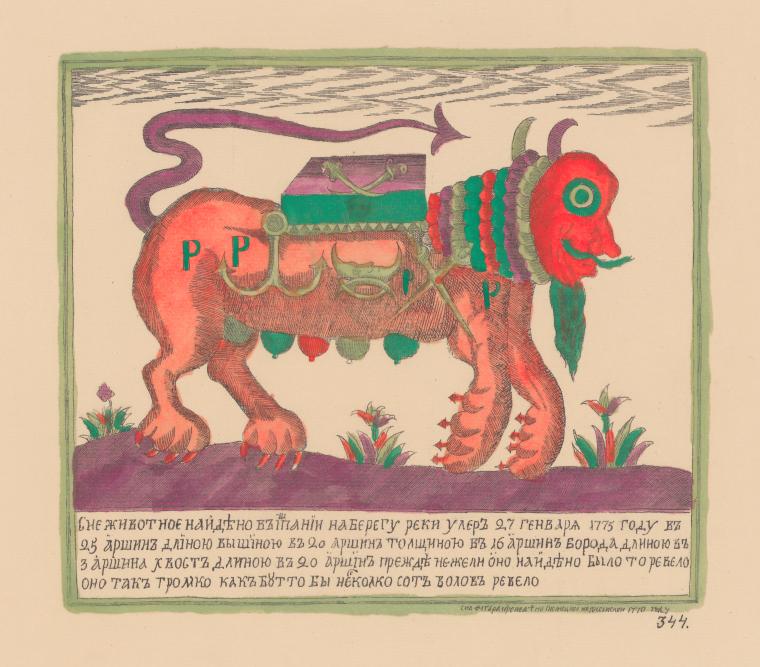

Zhivotnoe, naidenoe v Ispanii, 27 Ianvaria 1775 goda – An Animal Found in Spain, January 27th 1775

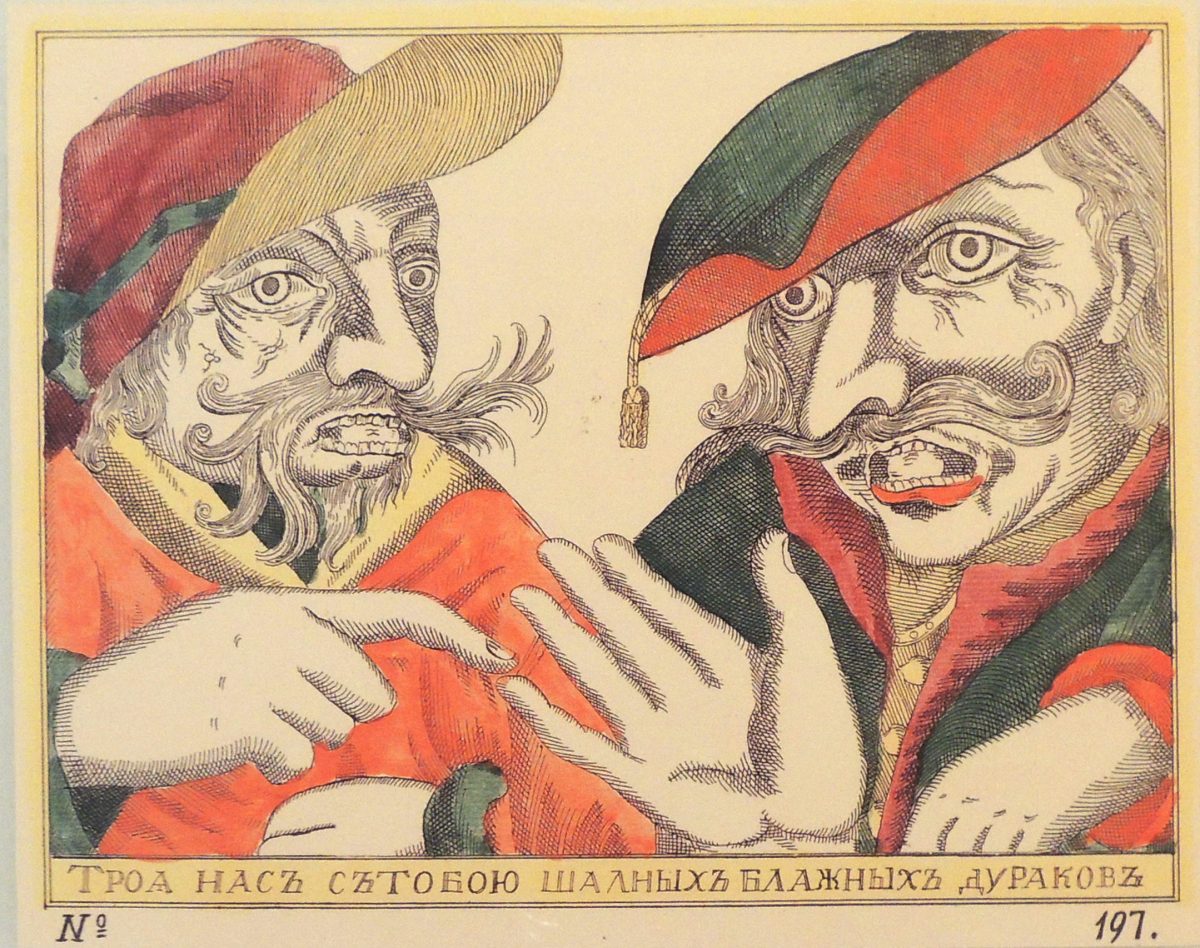

Two Fools

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.