“During the weeks and months following” the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center, Max Page writes in The City’s End, “two contradictory phrases were spoken over and over again…. On the one hand: ‘It was unimaginable.’ On the other: ‘It was just like a movie.’” For decades, Americans had, in fact, imagined, often with great relish, the destruction of New York City. In our “well-trained popular-culture imaginations, shaped by what we see when we turn on the television, go to a movie, or play a video game,” mass destruction seemed almost preordained, if also totally incredible in the global center of wealth and power.

Accumulating visions of the city’s fall were driven by “some of the most long-standing themes in American history,” Page writes: “the ambivalence toward cities, the troubled reaction to immigrants and racial diversity, the fear of technology’s impact, and the apocalyptic strain in American religious life.” Much of this animus has emerged in very literal ways in recent weather disasters in the Gulf Coast and, of course, the current pandemic, which finds Americans around the country willfully spreading the virus and wishing each other dead.

Fire in San Francisco following the great earthquake of 1906. View if from Gold Gate Park, Marin County, California. (USGS)

What must it have been like over 100 years ago—before the great deluge of disaster, zombie, and superhero movies—to have witnessed the near-destruction of a major American city? How did the survivors of the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake and resulting fires make sense of the events without a media entertainment complex to socialize them to catastrophe?

The film industry was in its infancy (though four filmmaking brothers were able to capture the aftermath on camera). But photography had evolved to meet the moment, and the many images of the disaster are harrowing, some of them full panoramic views taken from a kite 2,000 feet above the city.

Photographed by Arnold Genthe, George R. Lawrence, and others, the photos reveal the vast extent of the devastation and the scale of the military relief effort. They also sometimes show the breakdown of civil order, as in photographs of soldiers looting during the fires. But even more revealing are the written accounts of eyewitnesses and survivors. Filled with terror and confusion, they show victims of the quake reaching desperately for context, and either finding it in religion or losing the plot entirely.

One witness describes “a band of men and women” praying, “and one fanatic, driven crazy by horror, was crying out at the top of his voice: ‘The Lord sent it, the Lord!’ His hysterical crying got on the nerves of the soldiers and bade fair to start a panic among the women and children, so the sergeant went over and stopped it by force.” Another recalls the scene at the Market Street ferry as “bedlam, pandemonium and hell rolled into one…. Men lost their reason at those awful moments.”

The quakes and fires destroyed 490 city blocks, killed upwards of 700 people, and left a quarter of a million more homeless. Both rich and poor succumbed. “Even millionaires,” Rebecca Livingston writes at the National Archives Magazine, “their fortunes lost in the rubble, were homeless and without resources even to feed themselves.” As Arnold Genthe photographed the crowds among the debris, he found that the streets “presented a weird appearance”:

Many ludicrous sights met the eye: an old lady carrying a large bird cage with four kittens inside . . . a man tenderly holding a pot of calla lilies, muttering to himself; a scrub woman, in one hand a new broom and in the other a large black hat with ostrich plumes; a man in an old-fashioned nightshirt and swallow tails, being startled when a friendly policeman spoke to him, ‘Say, Mister, I guess you better put on some pants.’

By contrast with these grim scenes, “the philosopher Willam James described how in the aftermath of the earthquake,” Natalie Pellolio notes at the California Historical Society, “his students at Stanford University slept outdoors in order to ‘get the full unusualness out of the experience.’” Such “weird,” “ludicrous,” and “unusual” scenes were “not the visuals that San Francisco’s civic leaders sought to promote” as they pushed a united message of resilience and sought to rebuild immediately.

Without predigested narratives of mass urban destruction of a secular variety, many modern San Franciscans experienced the earthquake not “like a movie,” but as a “harbinger of uncertainty and radical possibility.” They did not all experience it in the same way, of course. Rich and poor alike may have been cast into the streets at first, but the old class and race divisions, as well as segregated refugee camps, soon became the order of the day. Livingston draws many parallels between the responses to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the circumstances of the 1906 quake, including the issuing of “shoot-to-kill” orders for looters, though soldiers and police themselves took part in the looting.

Maybe the popularity of “disaster porn” in mass media has as much to do with wish fulfillment as it does with historical trauma from actual disasters. But in some of the most telling commentary, from the other side of the country, H.G. Wells recorded the reactions he heard immediately afterward in New York on his first trip to the U.S. He published his impressions the same year in The Future in America: A Search After Realities:

It does not seem to have affected any one with a sense of final destruction, with any foreboding of irreparable disaster. Every one is talking of it this afternoon, and no one is in the least degree dismayed. I have talked and listened in two clubs, watched people in cars and in the street, and one man is glad that Chinatown will be cleared out for good; another’s chief solicitude is for Millet‘s ‘Man with the Hoe.’ ‘They’ll cut it out of the frame,’ he says, a little anxiously. ‘Sure.’ But there is no doubt anywhere that San Francisco can be rebuilt, larger, better, and soon. Just as there would be none at all if all this New York that has so obsessed me with its limitless bigness was itself a blazing ruin. I believe these people would more than half like the situation.

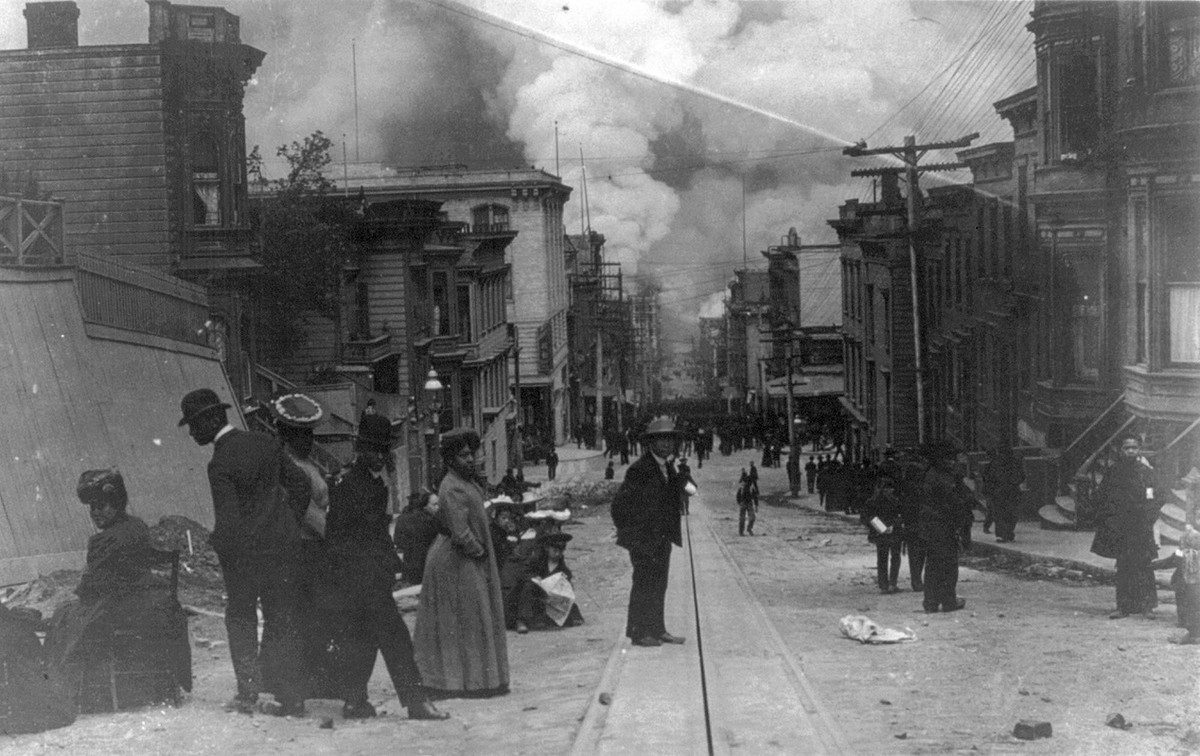

African American families on street during the San Francisco Fire of 1906; clouds of smoke billowing at bottom of hill in background. (Library of Congress)

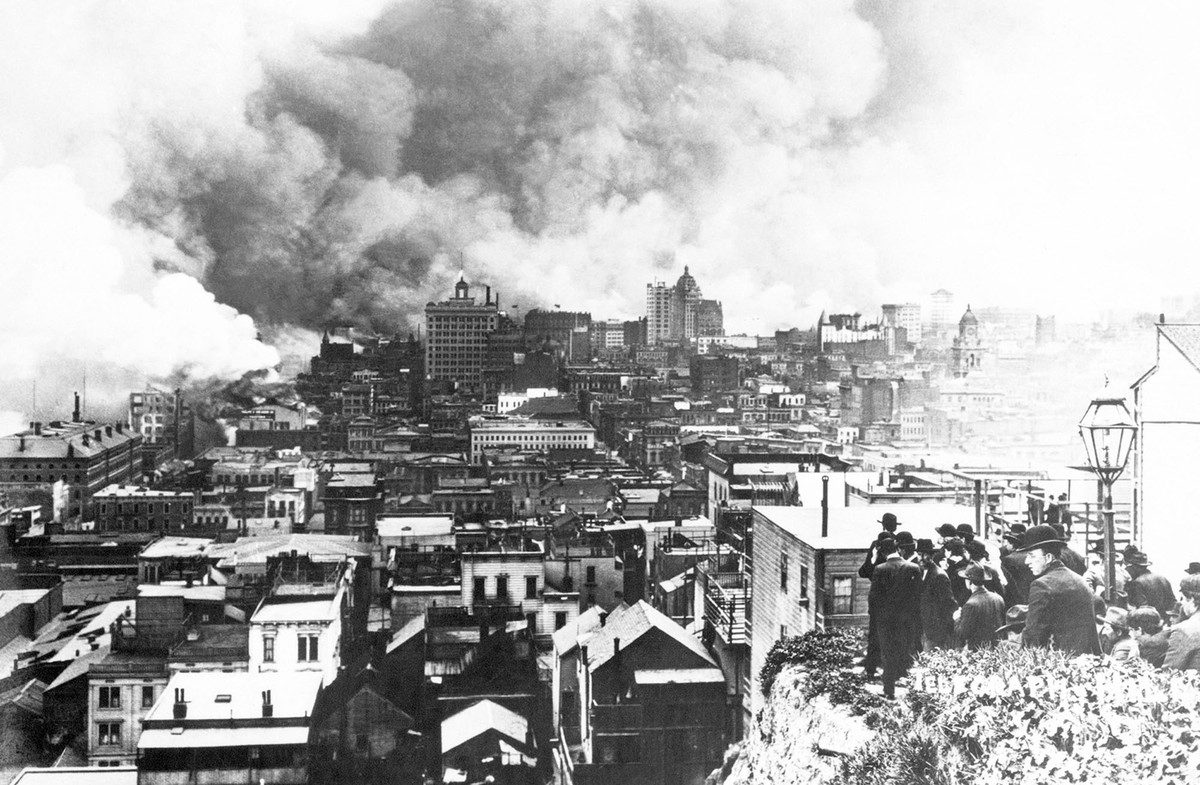

A crowd gathers at Telegraph Hill to watch the burning of San Francisco. The view is looking south. On April 18, 1906 at 5:15 AM a quake of 8.25 on the Richter scale hit San Francisco. Greater destruction came from the fires afterwards. The city burned for three days. The combination destroyed 490 city blocks and 25,000 buildings, leaving 250,000 homeless and killing between 450 and 700. Estimated damages, over $350 million. (National Archives)

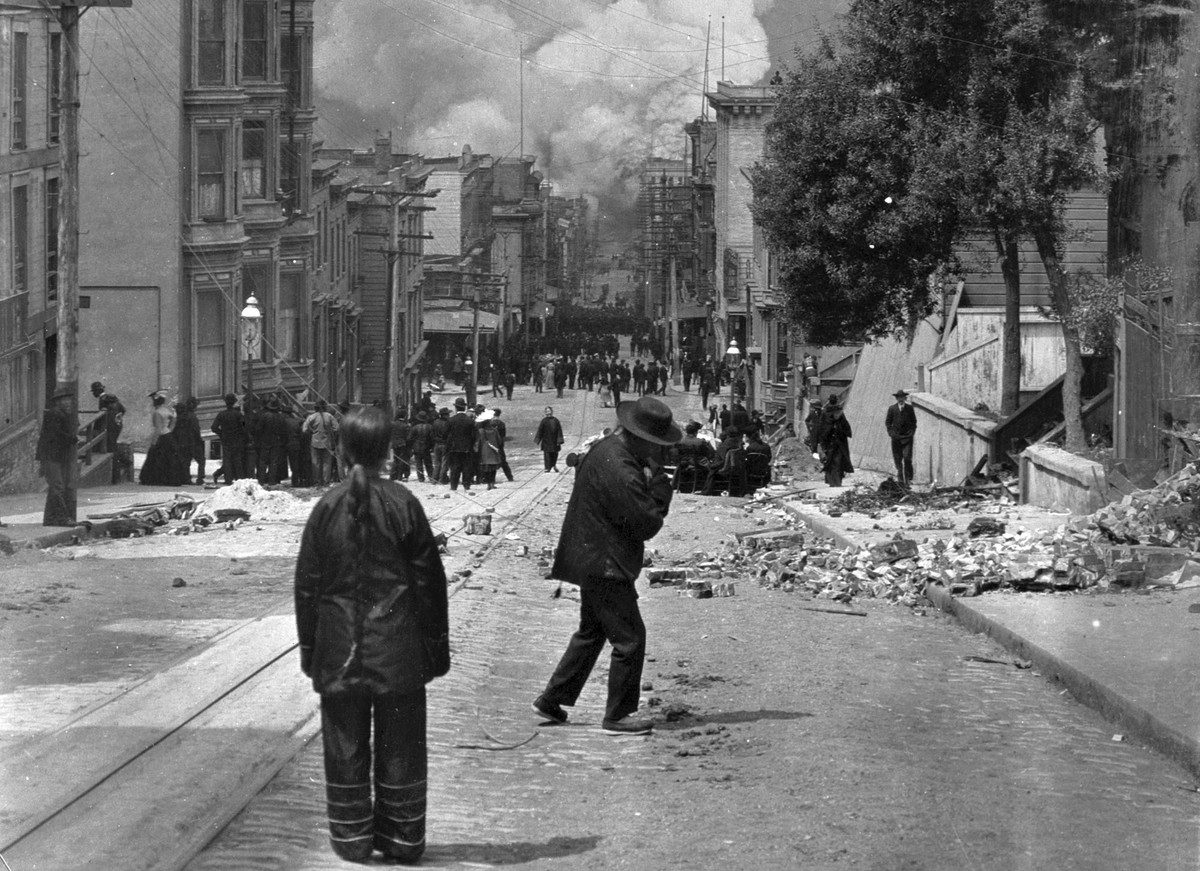

View of earthquake damage and fires. Across California Street, south from Nob Hill. 11 am, April 19, 1906. (USGS)

Engine retiring from fire to take up new stand. 9 am, April 19, 1906. (USGS)

View northeast from City Hall showing massive damage to San Francisco. 1 pm, April 19, 1906. (USGS)

Souvenier hunters. These in the early stages caused considerable trouble to the military authorities. (National Archives)

Ruins of San Francisco, Nob Hill in foreground, viewed from Lawrence Captive Airship, 1,500 feet elevation, May 29, 1906 — 41 days after the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and resulting fires. (Library of Congress)

Ruins of San Francisco, Nob Hill in foreground, viewed from Lawrence Captive Airship, 1,500 feet elevation, May 29, 1906 — 41 days after the Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and resulting fires. (Library of Congress)

Sacramento Street, from Nob Hill, with the Ferry Building at foot. (National Archives)

Looking up California St. from Sansoney [i.e. Sansome] St. (Library of Congress)

San Francisco City Hall and dome at McAllister Street and Van Ness Avenue.

The toppled statue of Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz, scientist and scholar, knocked from the facade of Stanford University’s zoology building in April of 1906. (Library of Congress)

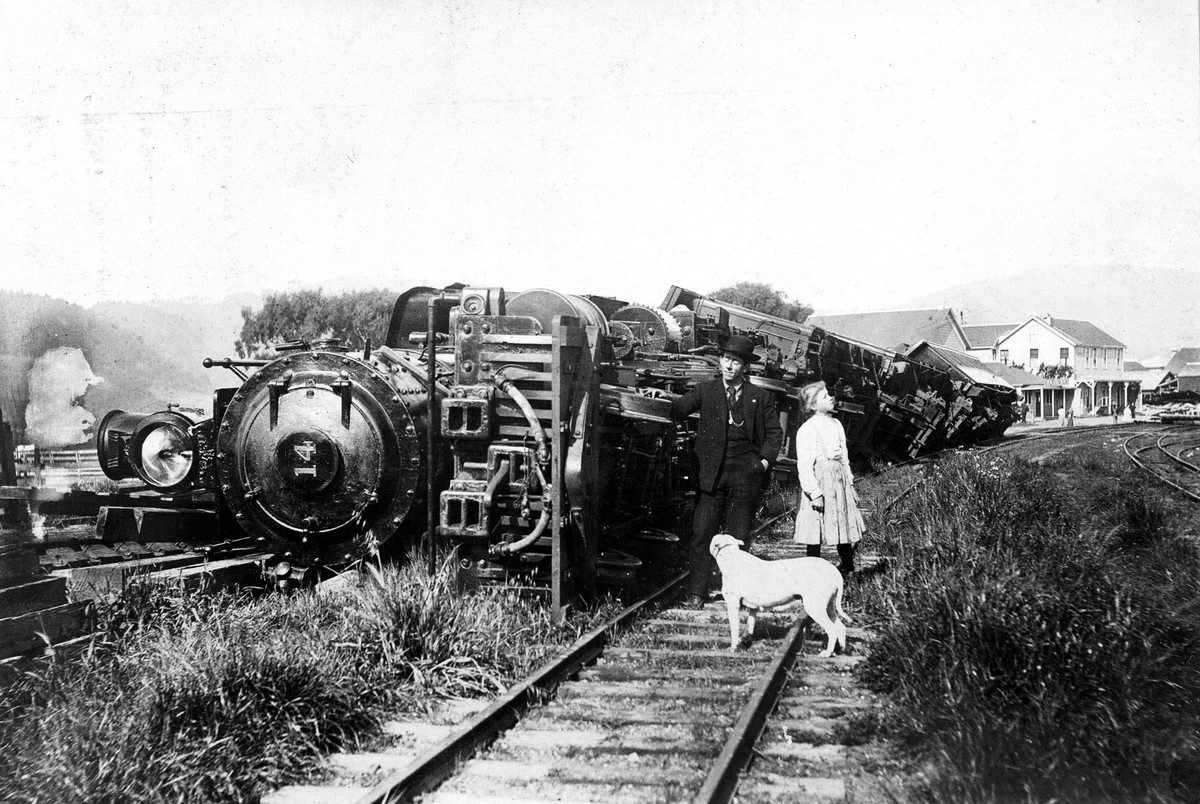

Train thrown down by the earthquake at Point Reyes Station. The train was standing on a siding. Beyond are the buildings of the Point Reyes Hotel and, on the extreme right, the ruin of a stone store which was shaken down. (USGS)

Cooking in the street. (Library of Congress)

Up Market St. from Montgomery St. (Library of Congress)

Junction of Sacramento, Market, and Embarcadero Streets, and part of the car track loop in front of the Ferry Building.(National Archives)

California Street looking east from Grant Avenue, which was DuPont Street in 1906. The immediate part of this district is that of Chinatown, the lower part is the financial district showing Merchant’s Exchange Building.

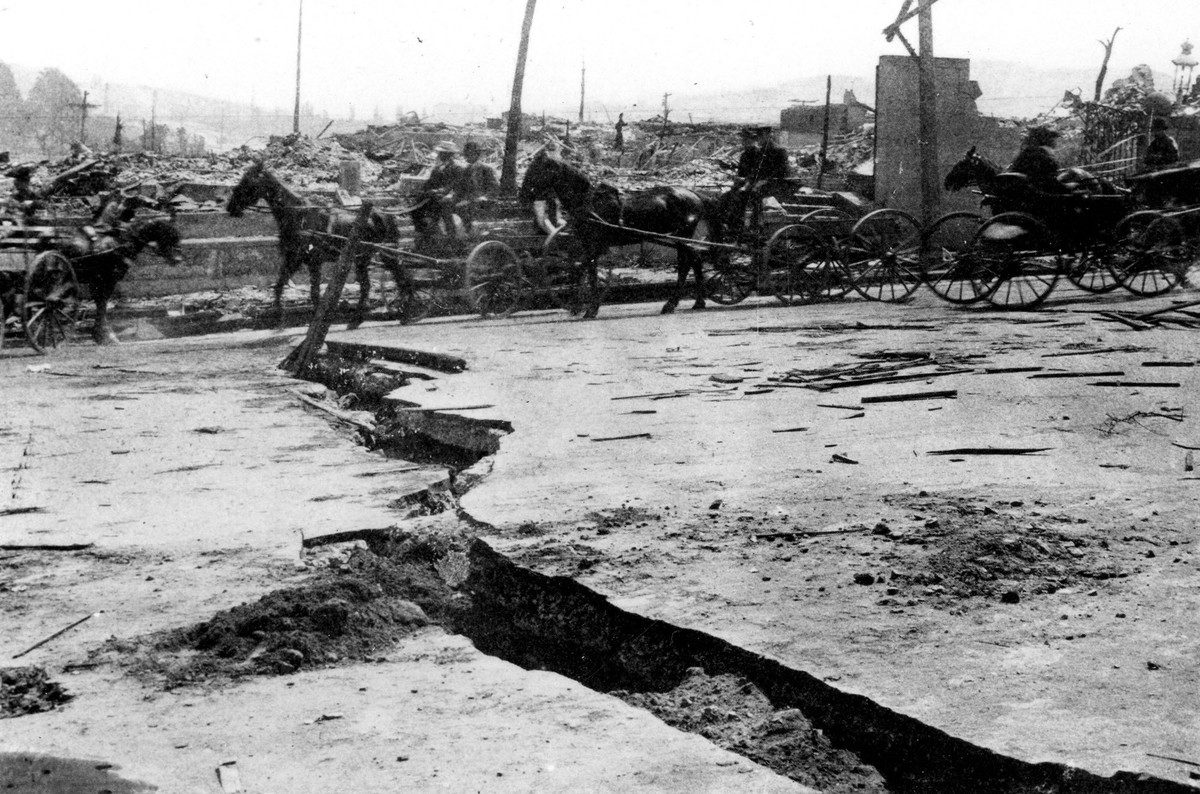

Disruption of Van Ness Avenue over a filled-in ravine. Lateral movements as great as 3 feet (0.9m) and vertical movements as great as 2 feet (0.6m) occurred at this location. Photograph previously published by Zeigler (1906) with caption “Break in asphalt paving on Van Ness Avenue near Vallejo Street. View shows horse-drawn wagon and buggy traffic. City and County of San Francisco, California. 1906. (USGS)

Market Street at the junction of Powell and Market, looking east toward the Ferry Building. The large building to the left is the Flood Building. The side wall of the first large building is the Emporium, the largest department store in San Francisco. On the right is the San Francisco Call Building. On the left, the structure with the derrick is the new addition to the De Young Building, and in the extreme distance, at the end of Market Street, is the tower of the Ferry Building. (National Archives)

Pine St. below Kearney St. (Library of Congress)

Preparing hot food for the refugees. (George Williford Boyce Haley / National Archives)

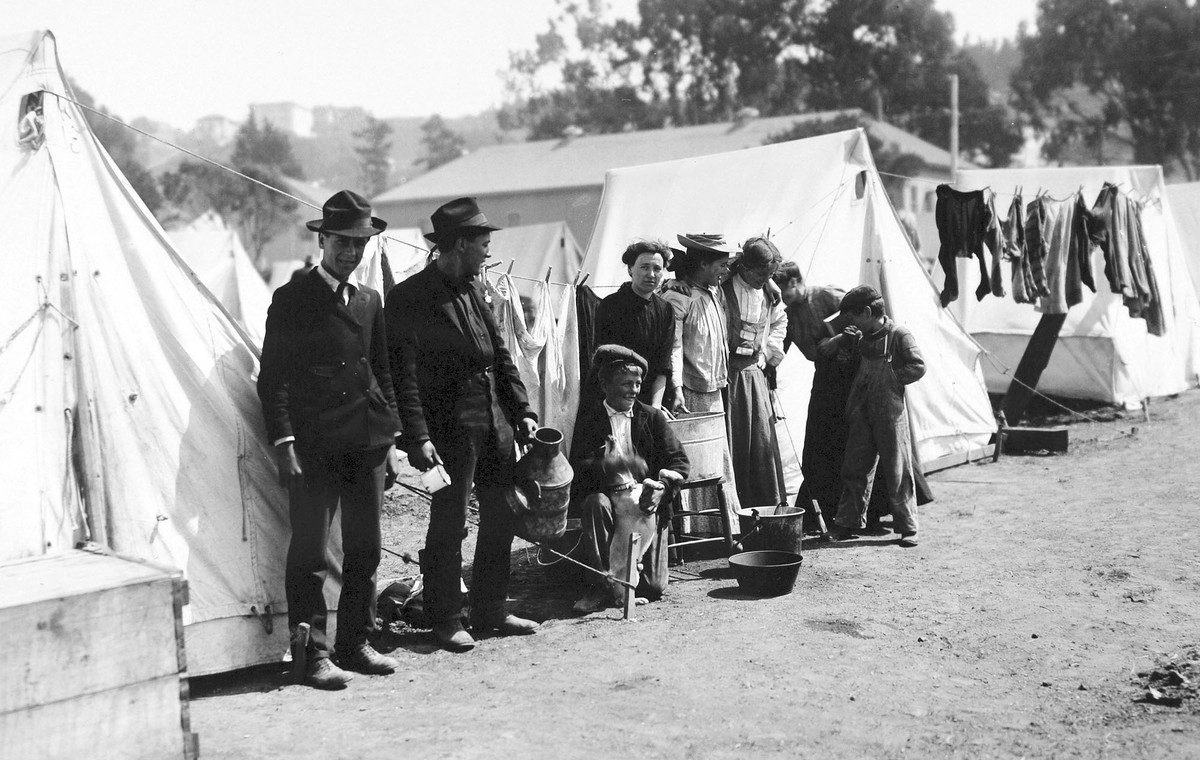

Families take refuge in tents. (National Archives)

Market Street, looking west toward the Rwin Peaks, from Battery Street. Both sides of Market Street lined with ruined buildings from Battery to Powell.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.