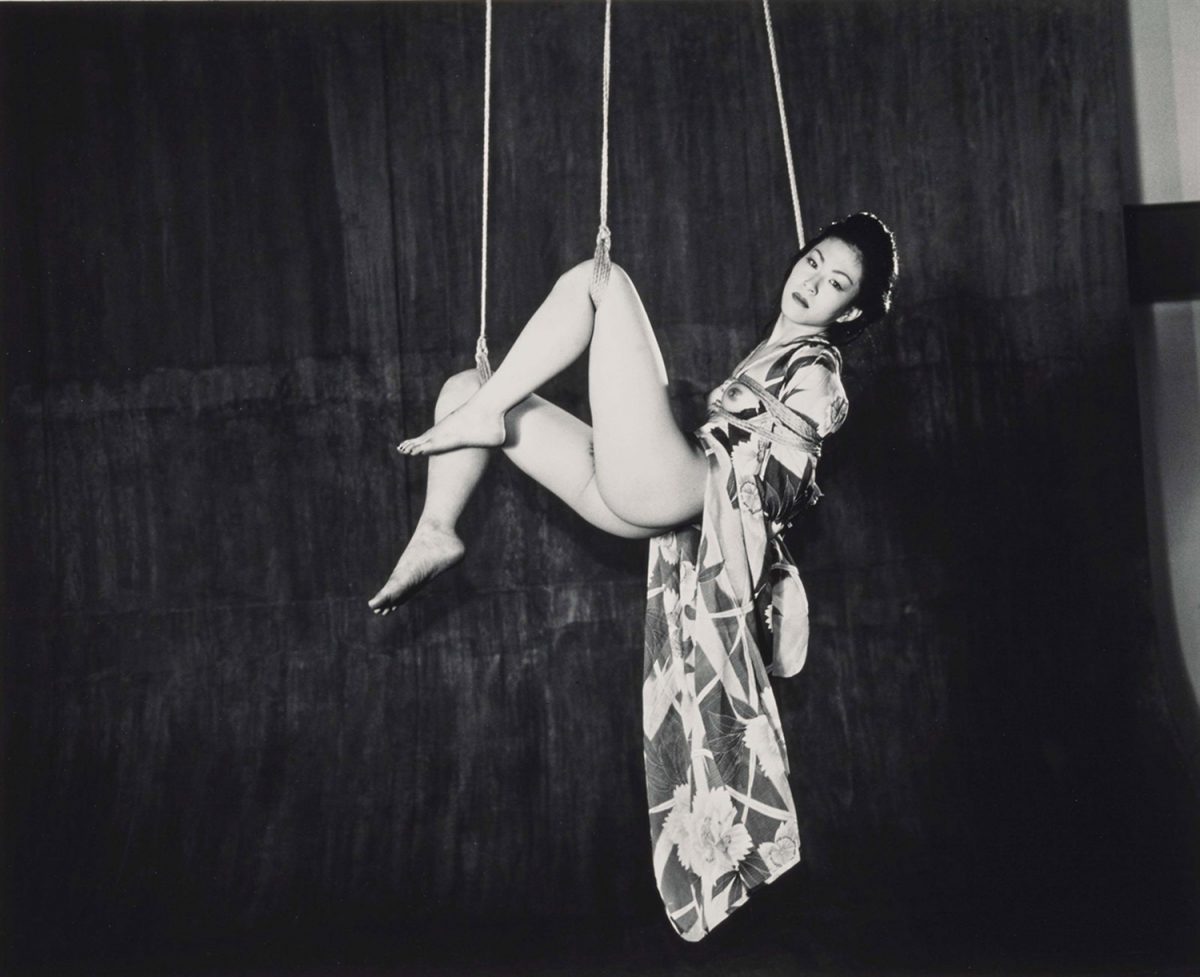

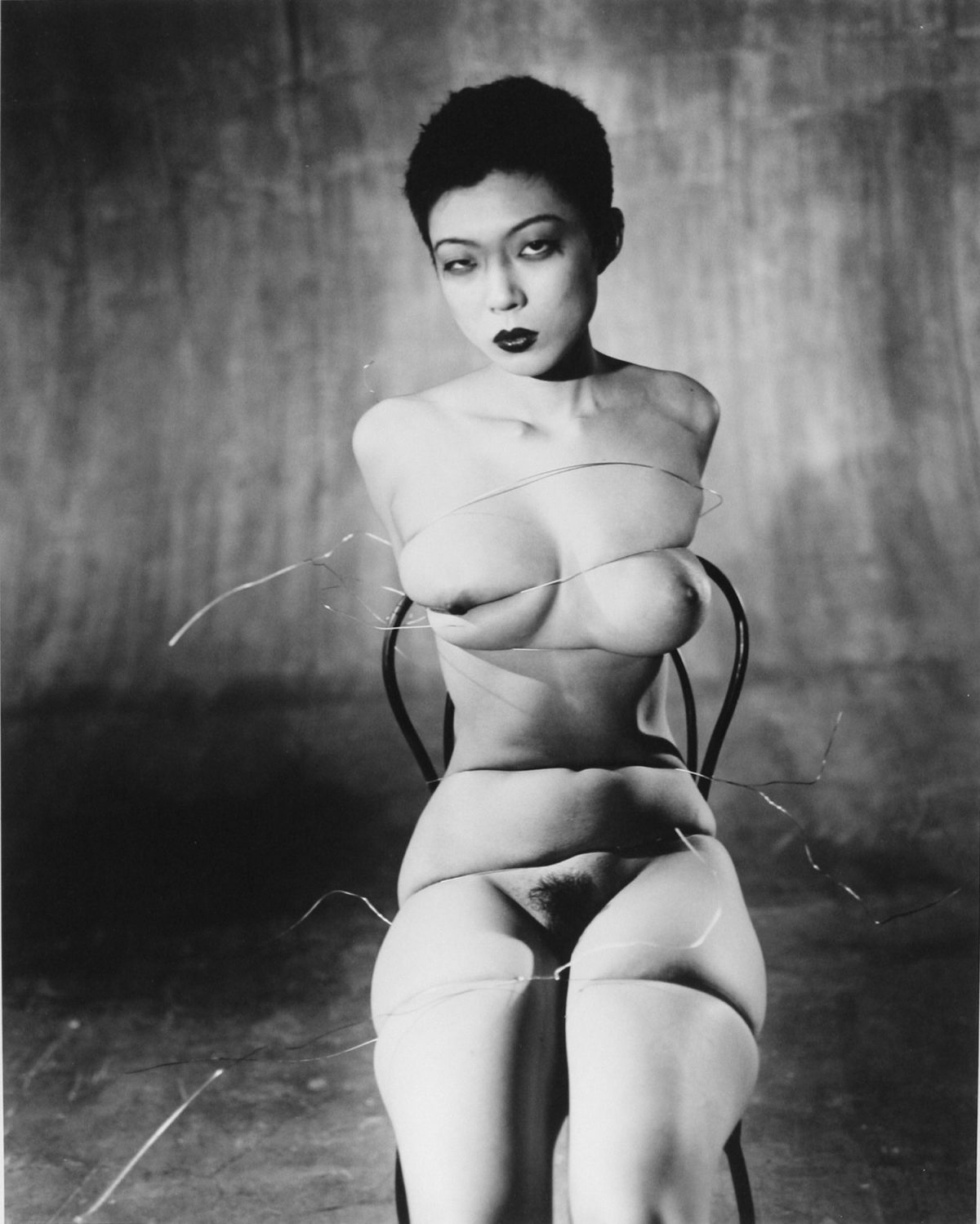

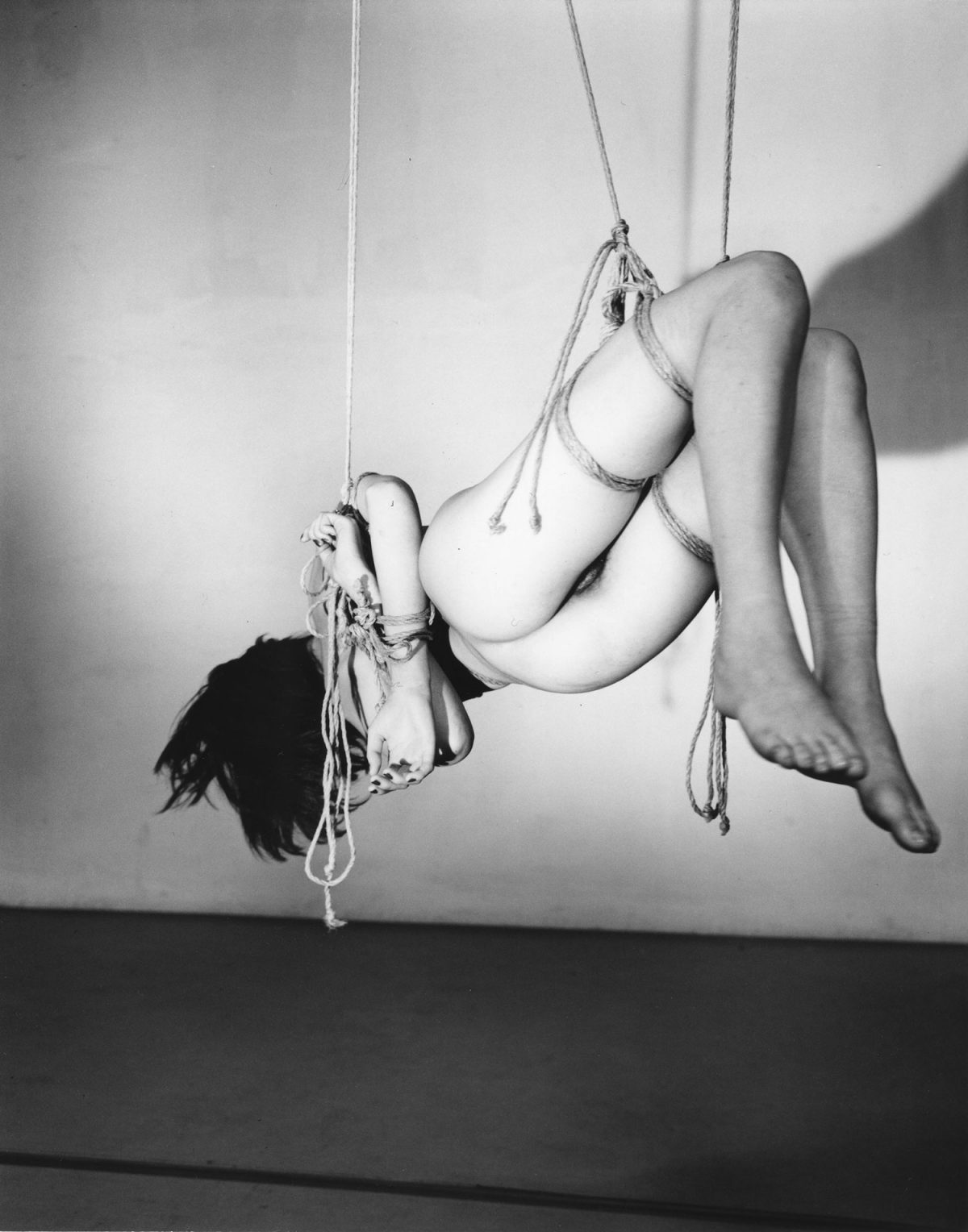

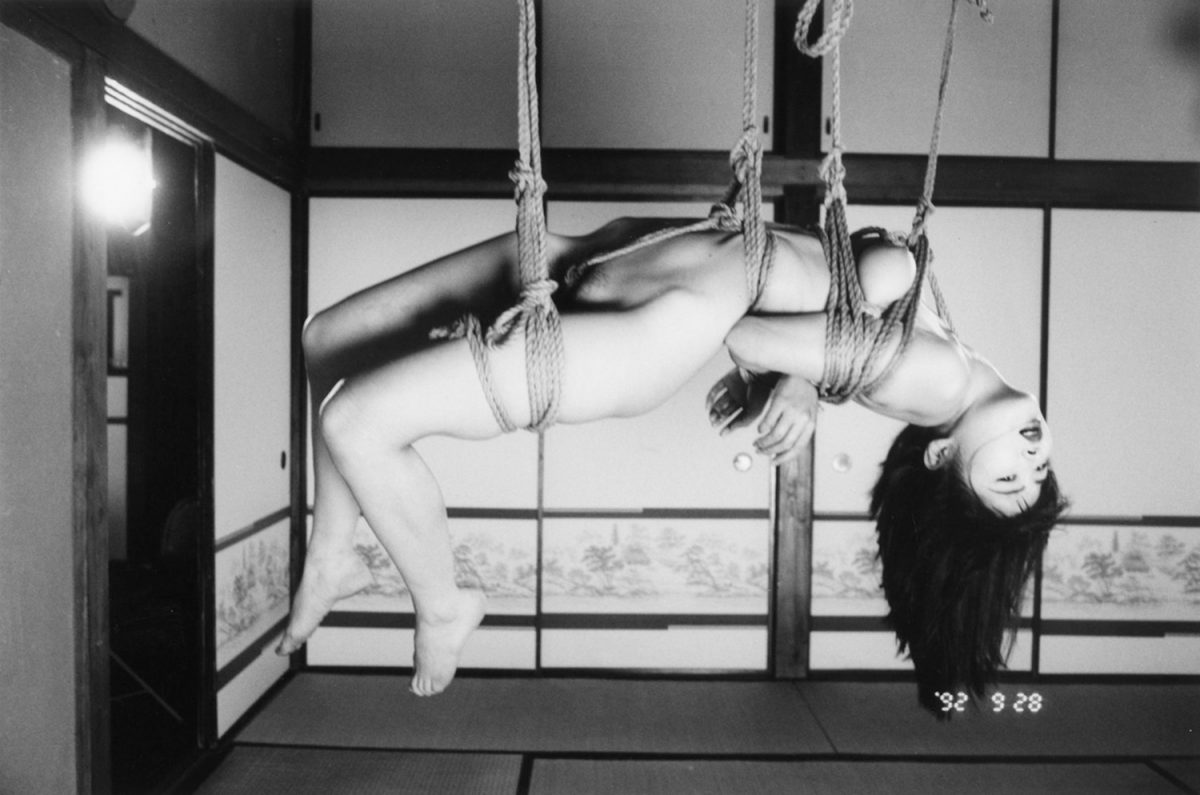

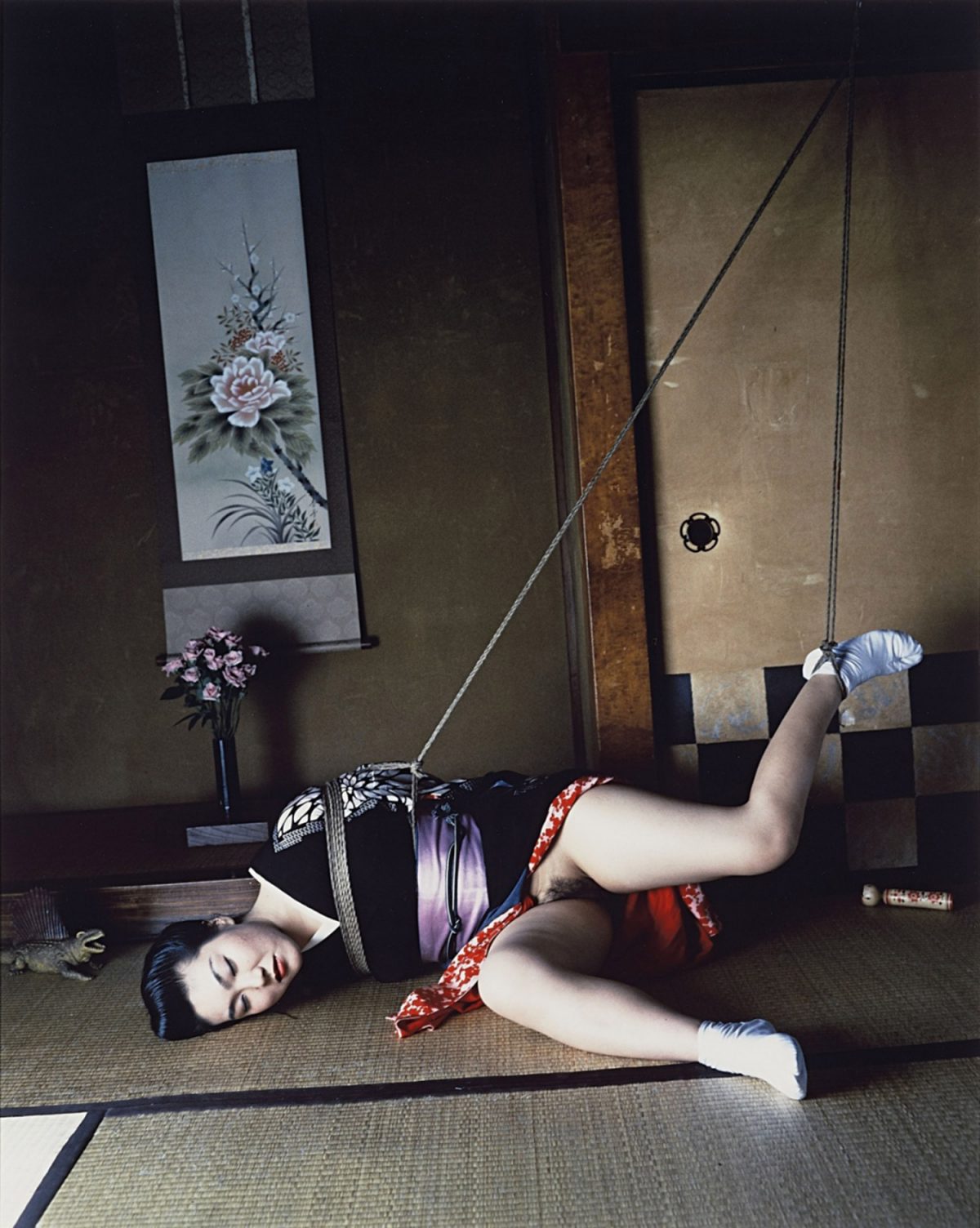

Nobuyoshi Araki’s photography career has been marked by shock and controversy over his choice of subjects. Though his photographic interests have been wide-ranging since he began in the early 60s, he’s best known for his notorious portraits of mostly naked women posed in a Japanese style of rope bondage called Kinbaku-bi (“the beauty of tight binding”). This work has earned him considerable acclaim, opprobrium, and legal consequences. “In 1988,” notes New York’s Yoshii Gallery, “police blocked the sale of the magazine Shashin Jidai because Araki’s risqué photographs were featured in it. Araki was also charged with obscenity during a 1992 exhibition, for which he was fined 300,000 Yen. This was followed by the arrest of a gallery curator who exhibited his graphic nudes in 1993.”

The censorious response might lead newcomers to think that kinbaku-bi constituted a new transgressive form in Japan. But several decades earlier, artist Seiu Ito “introduced 20th century concepts to 19th century ideals,” writes The Absolute, “taking inspiration from the kabuki theater and torture methods of the late Edo Period.” Like Araki, Ito “would bind his models (among them his second wife) with rope, sometimes even attaching them to other devices or hanging them upside-down.” Ito used his photographs as source material for ukiyo-e-inspired drawings and also displayed the photos themselves as works of art. His work was “the first to be explicitly sadomasochistic,” writes Brooke Larsen, inspiring what became a creative movement in the 1920s and 30s, Ero-Guro, or the “erotic grotesque.”

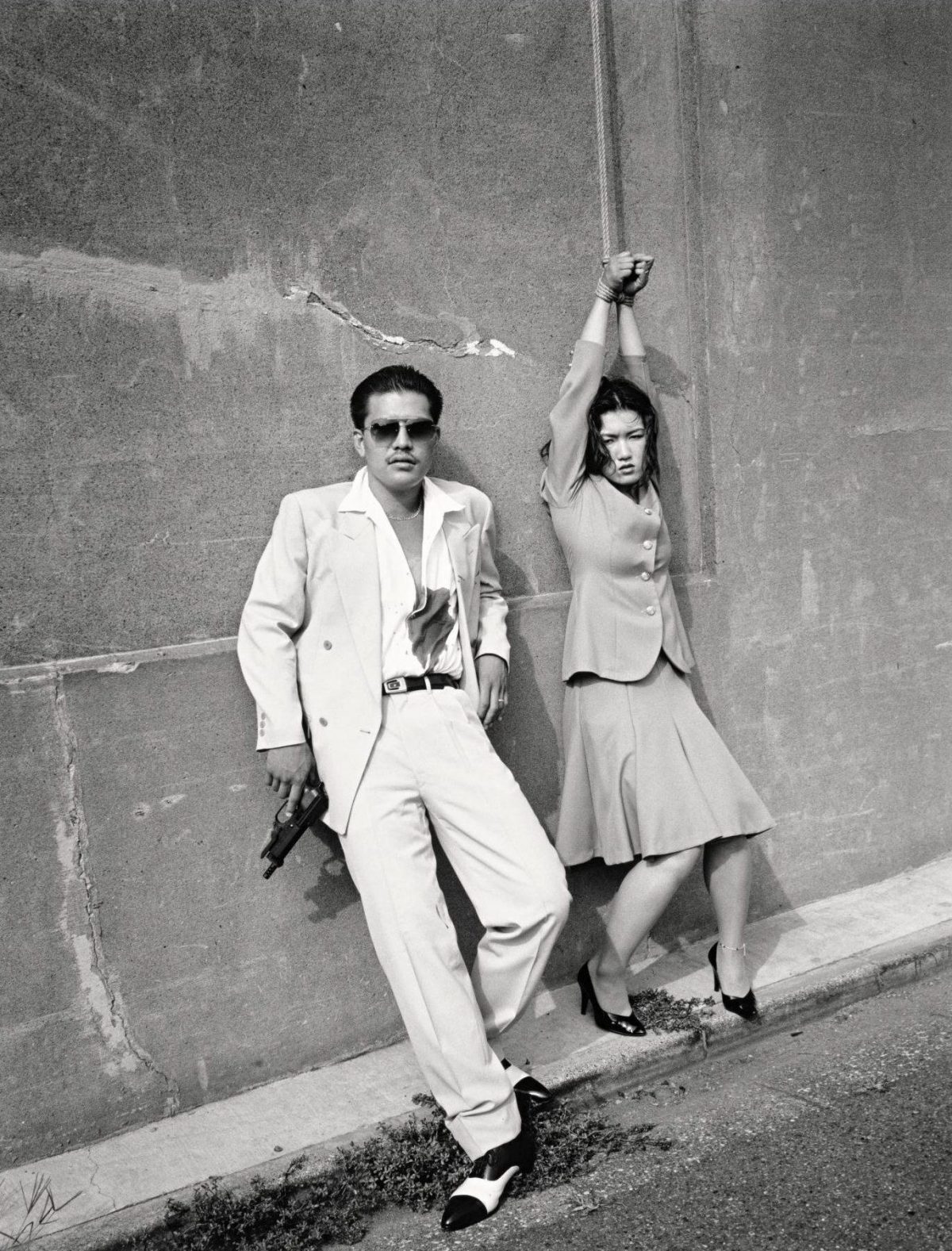

This history is essential background for understanding Araki’s work. Like Ito and other early 20th-century Ero-Guro artists and photographers, Araki sexualizes an object—rope—traditionally used in both sacred contexts and as a baroque instrument of social control. Such work became quite popular among Westerners. “After WWII,” Larsen points out, “American and Japanese fetish magazines depicting bound women began to circulate, causing such imagery to become more widespread.” What was Araki’s great crime in exhibiting his photographs? While he did not invent rope bondage photography, any more than Robert Mapplethorpe invented queer BDSM photography, both artists brought what was confined to the margins and private spaces into the galleries of the fine art world, blurring the lines between art, erotica, and porn.

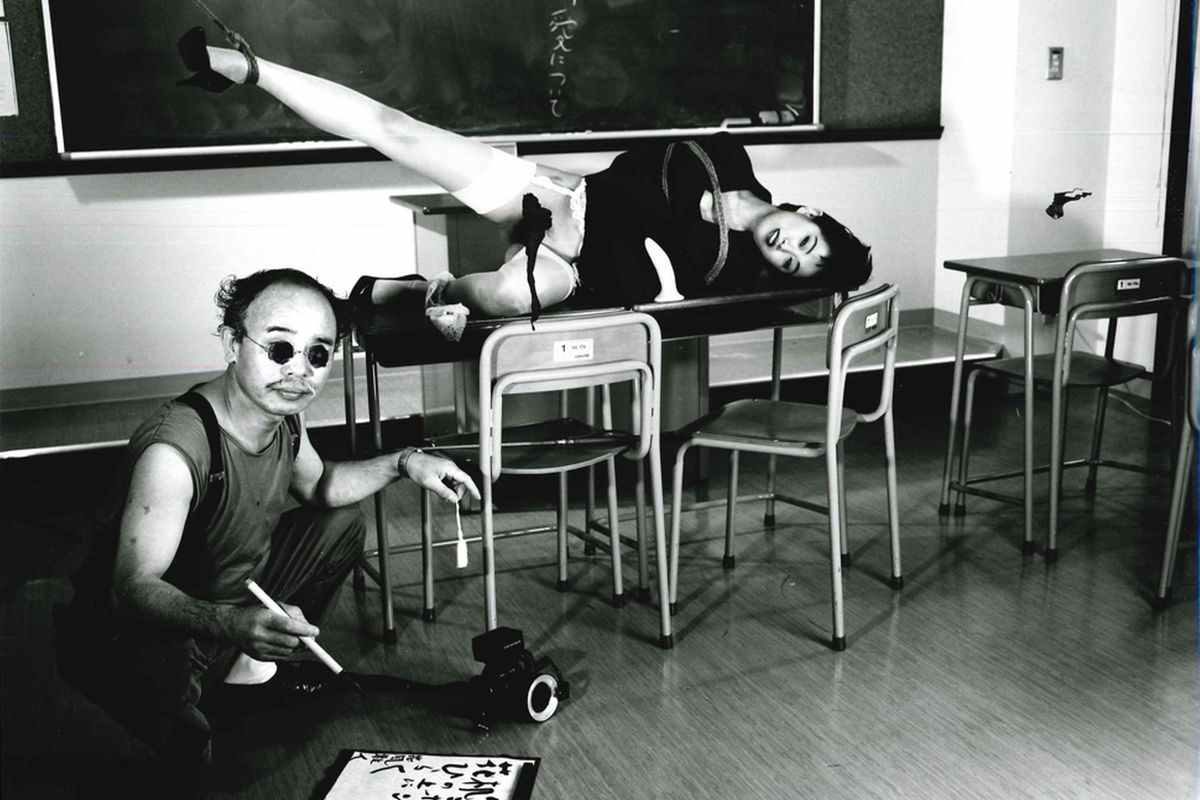

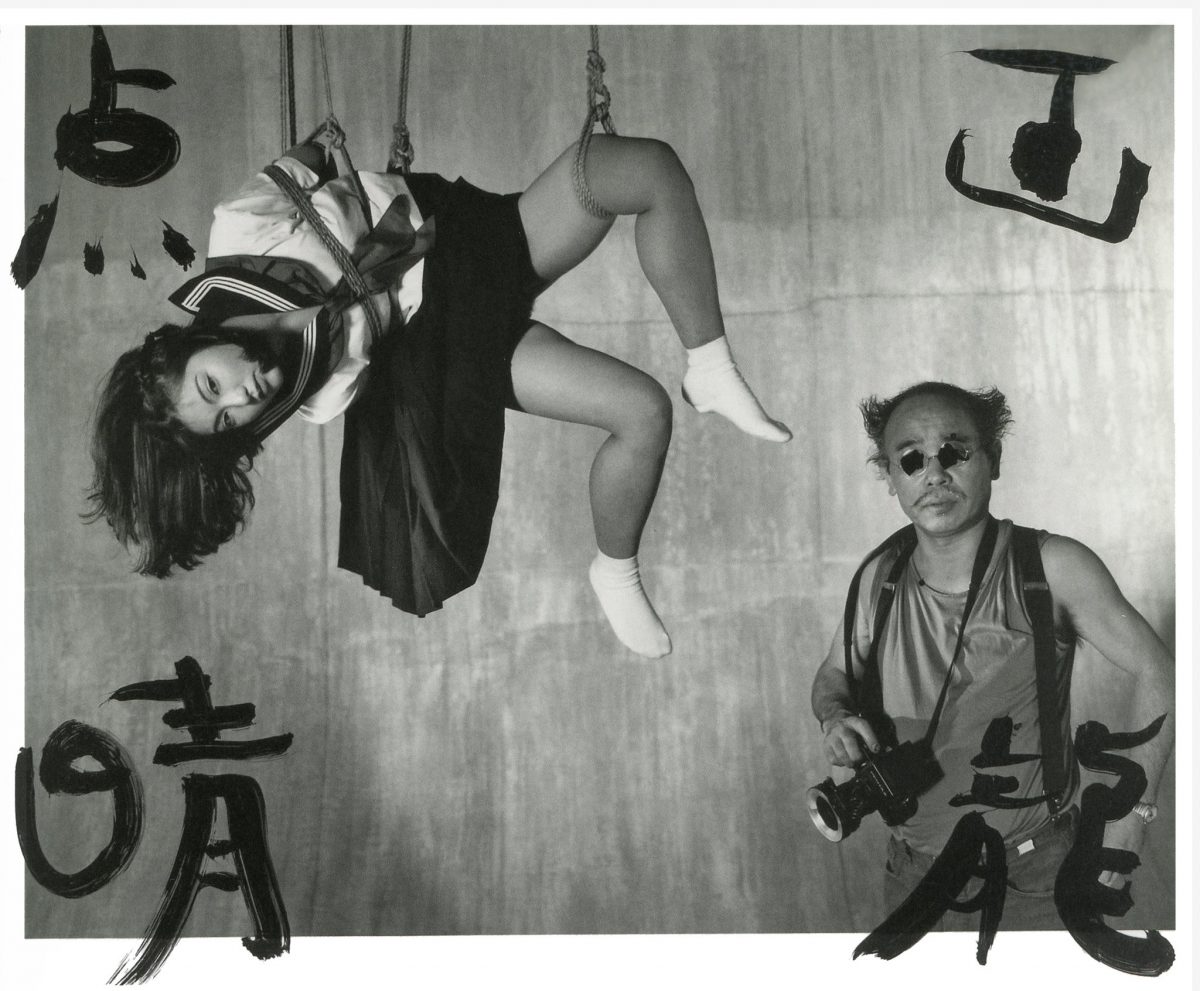

The moral authorities construed exhibiting such art as an unacceptable crossing of boundaries, a legitimizing of images that disturb and arouse the public. Subtly embedded in Araki’s photography is, perhaps, a critique of the consumption of Kinbaku-bi as a form of ritualized pornographic torture. In most Kinbaku-bi images, models grimace in pain, hang their heads, or look away in shame and submission. Araki’s models generally stare directly at the camera, and into the viewer’s eyes. They appear calm, self-possessed, and in control. The shift is akin to Pablo Picasso’s radical Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, in which the denizens of his brothel steadily hold the viewer’s gaze, their bodies disfigured by his savage brushstrokes. This was, in part, Picasso’s answer to the exoticized, submissive odalisques of Neoclassical erotic painting. Araki’s photos, especially his experiments with damaged and corroded film, may similarly enter into dialogue with the tradition of erotic art in Japan. His work also incorporates several autobiographical elements, and he himself appears in many Kinbaku-bi portraits, turning his gaze around to look at us.

Picasso was not known for treating any of the women in his life very well, to put it mildly. Araki has also come under intense scrutiny and criticism after one of his former models, Kaori, with whom the photographer had a sexual relationship, revealed a pattern of coercive, exploitative behavior in 2018. “He treated me like an object,” she wrote in a blog post, a remark that speaks to both unequal power dynamics in sexuality and in the precarious labor market of nude models with little legal agency. Araki is still working and exhibiting erotic photos. A new hardcover book from Skira Editore covers his career from 1963-2019, a body of work that includes far more than Kinbaku-bi. A recent show of Araki’s bondage work at the Museum of Sex in New York incorporated Kaori’s comments in its exhibition materials, adding another layer of interpretive complexity, and an unsettling traumatic overtone viewers have to confront. “Looking back now,” writes Kaori, “everything was excessive and extreme. Something in me was numb. He asked me to do abnormal things, and I did them as if they were normal.”

via Scene 360

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.