The Chicken of Tomorrow, John E. Weidlich Collection at USDA

In 1948, Audio Productions produced The Chicken of Tomorrow, a film to show American diners “how scientific agriculture changes the life and taste of the chicken”. It’s an informative film with a great title, winning much praise at the eighth World Poultry Congress in Copenhagen (WPPPC) (August 20-27, 1948). You can watch it at the end of this story. But before then, some background.

The WPCC is an international gathering of poultrymen first convened in the Hague, the Netherlands, in 1921. The WPP produced for the dissemination of knowledge two periodicals: the International Review of Poultry Science (1928-1940) and the World’s Poultry Science Journal (1945 -), the latter a collection of review articles on “virtually all aspects of poultry production and poultry science” (make your submissions here).

The WPCC’s noble aim is to feed the world with cheap, healthy protein, the miracle of the post-war age. Chicken, once a special treat, is now a mainstay of the world’s daily diet. The numbers are staggering. At least 50 billion chickens worldwide are reared each year for their meat; another five billion are kept as laying hens, according to the International Egg Commission, which represents the egg industry. The National Chicken Council estimates per capita consumption of chicken in the U.S. at over 80 pounds a year.

The Great Depression dream of “a chicken in every pot” has become a reality.

What’s big now was growing fast then. The film’s narrater, Lowell Thomas (April 6, 1892 – August 29, 1981), points out, “Did you know that poultry is the nation’s third largest crop?” Thomas, a broadcast journalist, had the facts and a reputation for breaking a story. Lowell was, after all, the man who had met T.E. Lawrence during World War I and helped create the legend of “Lawrence of Arabia” with a 1919 film entitled With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia.

Now Lowell had other bigger fish to fry, namely chickens. In the film he spots a fine breed of bird: “Dressed White Hocks representing Mrs H W Lindhart of Chillicoffy, Missouri, had the best skin texture, the least dark meat, and the best covering of fat.” Could Mrs Chillicoffy (skin texture and fat not noted) or her crop be The Chicken of Tomorrow? Were her birds sufficiently resistant to disease to be a reliable source of healthy food for a growing population, feeding people averse to food poisoning from bad hens and rotten eggs laced with Salmonella, what one British medic told the 1949 Royal Sanitary Institute Congress represented the “largest genus of pathological significance”? That’s not to say the USA was exactly like Britain. The US was far advanced in matters of food preparation and hygiene than its former Old World rulers. In America 1956, a land with a population nearly four times the size of England and Wales, the total number of food poisoning cases stood at 11, 133. In 1957 the figure for England and Wales was 15,100 (source: Salmonella Infections, Networks of Knowledge, and Public Health in Britain, by Anne Hardy.)

English visitors to the Poultry Department at the University of Connecticut Via

But how did it all begin, this contest to find the Chicken of Tomorrow?

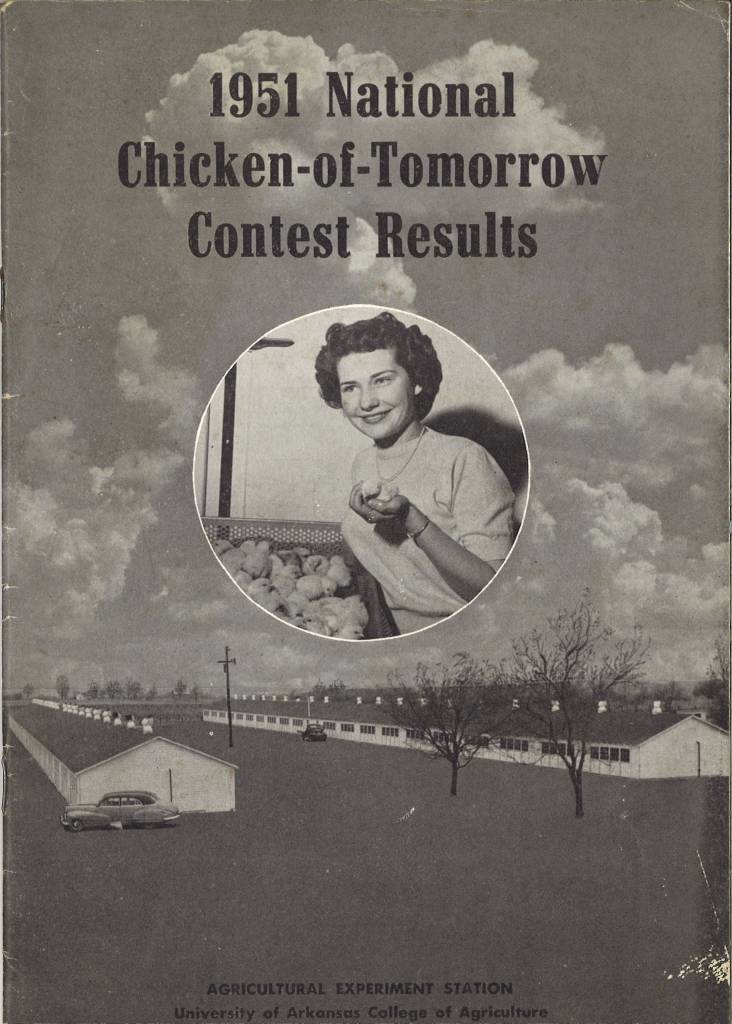

The University of Arkansas has news:

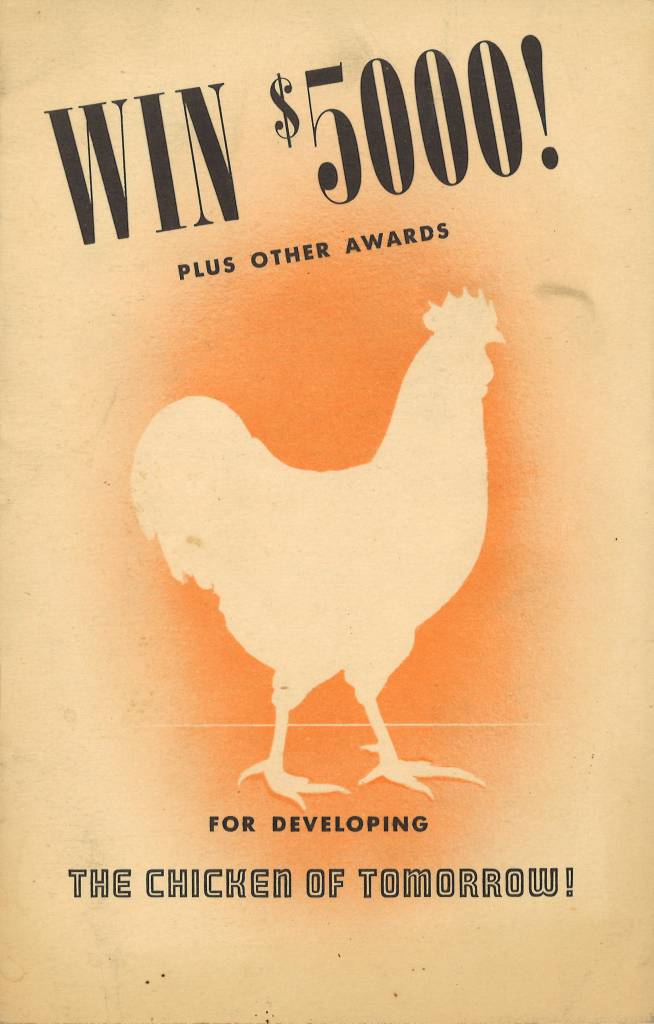

The Chicken-of-Tomorrow program, to encourage breeding chickens for superior meat, began on a state level in Arkansas in 1946. State Chicken-of-Tomorrow contests were held in 1946 and 1947. The first national finals were held in 1948 (Arkansas was not represented in these, though there was another state contest in 1948). Then another series of contests was started in 1949, culminating in the national Chicken-of-Tomorrow finals in 1951. These contests were held at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, during the week of June 11-16. In addition to the contest iteself, “Chicken-of-Tomorrow Week” featured exhibits, tours, concerts, dances, a rodeo, dinners, a parade, and a poultry forum. Two buildings were constructed on the University Experimental Farm for the event.

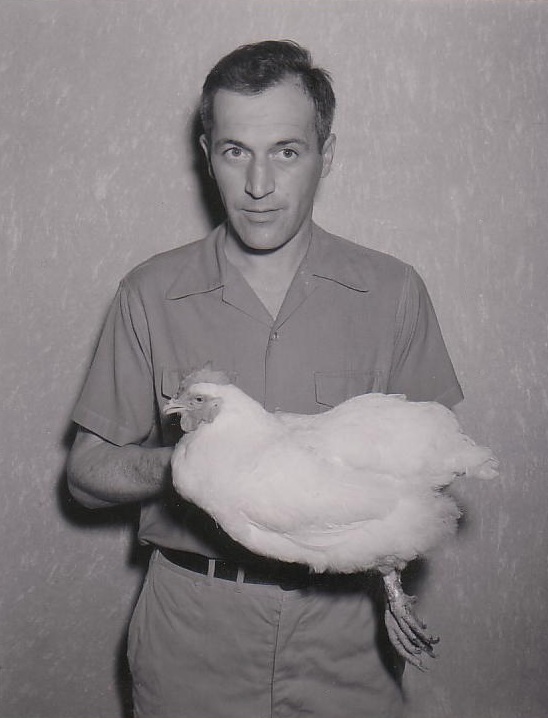

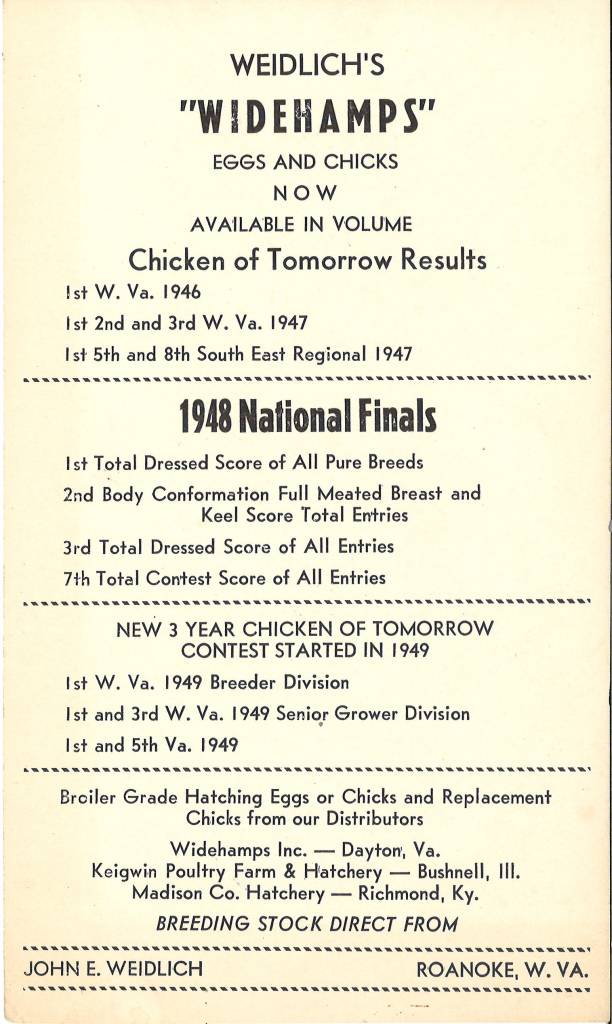

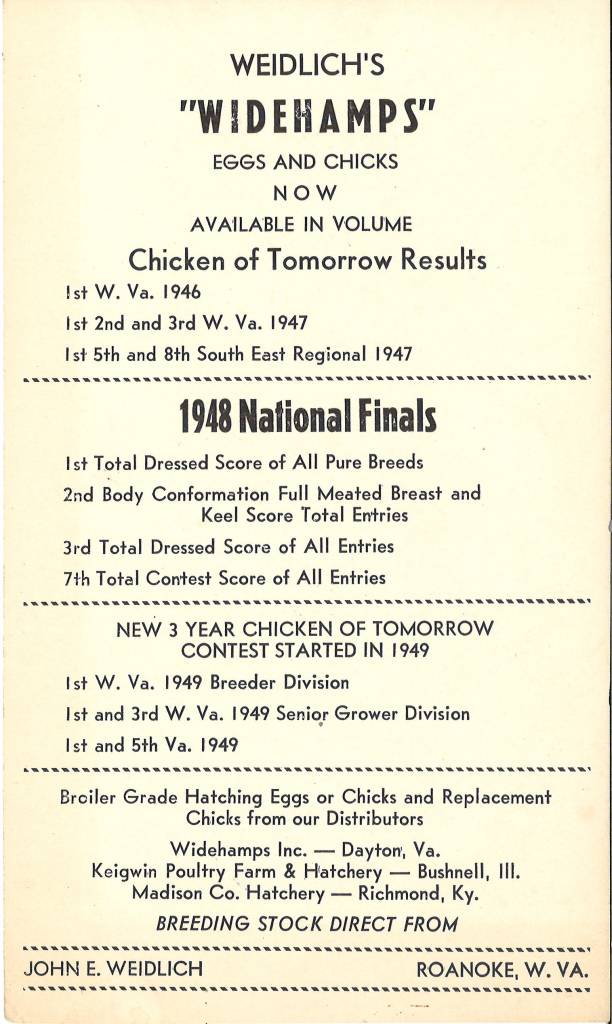

From the John E. Weidlich Collection at USDA

The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy notes:

In 1945, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (or the A&P as it was universally known), the country’s largest poultry retailer, sponsored a national contest in partnership with USDA to produce a breed of chicken that would grow bigger, faster and put on weight in all the right places. The idea that a supermarket and the USDA would partner to develop a breed of chicken seems odd today…

Through vertical integration and a policy of demanding volume discounts from manufacturers and wholesalers, A&P drove thousands of Mom and Pop retailers out of business. In 1945, the U.S. Justice Department won a conviction of A&P for criminal restraint of trade. The conviction had little impact on A&P’s business, but the giant supermarket chain took every opportunity during the trial and appeal to improve its image through press releases and public service work. The Chicken of Tomorrow contest was part of A&P’s damage control.

![Regional Meeting of Chicken of Tomorrow Contest Leaders Subjects: Poultry Item identifier: ua023_007-007-bx0022-002-002 Created Date: 1949-10 Description: Transcribed from back: Oct. 1949 Sir Walter Hotel-Raleigh, N. C. Regional Meeting of "Chicken of Tomorrow" contest leaders. 1- C. J [illegible] 2. Mrs. R. S. Dearstyne 3-4 [blank] 5-H. L. Shrader 6-R. S. Deastyne 7-I. O Schaub 8-Mrs. Schaub 9-Mrs. C. F. Parrish 10-[blank] 11-Dr. Peirce 12-Mrs. O. E. Golf 13-Ted H. Ash - W. Va. 14-Peterkin - S.C. 15-[illegible]](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/chicken-of-tom-1280x990.jpeg)

Regional Meeting of Chicken of Tomorrow Contest Leaders, 1949-10 Transcribed from back: Oct. 1949 Sir Walter Hotel-Raleigh, N. C. Regional Meeting of “Chicken of Tomorrow” contest leaders. 1- C. J [illegible] 2. Mrs. R. S. Dearstyne 3-4 [blank] 5-H. L. Shrader 6-R. S. Deastyne 7-I. O Schaub 8-Mrs. Schaub 9-Mrs. C. F. Parrish 10-[blank] 11-Dr. Peirce 12-Mrs. O. E. Golf 13-Ted H. Ash – W. Va. 14-Peterkin – S.C. 15-[illegible] 1949. Via

First Prize Winner of Chicken-Of-Tomorrow Contest 1949. Left to right: H. L. Shrader, USDA; Lloyd A. Bell, A&P Food Stores; H. Bernard Helm’s, Monroe, N. C. and C. J. Mairpin. Via NCSU

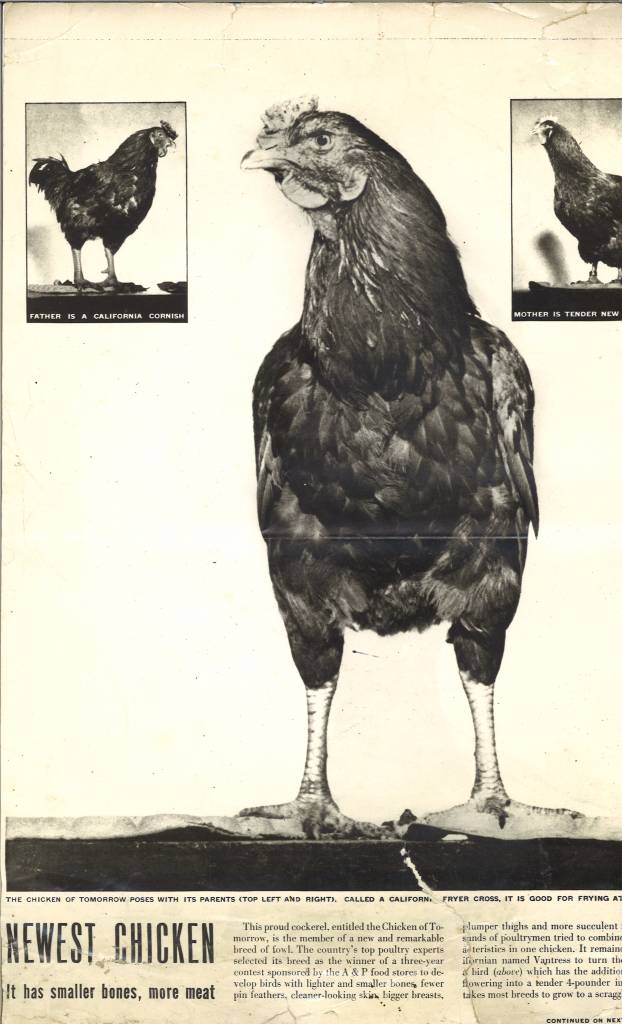

Farmers and breeders from across the country took part, submitting eggs for hatching at specially built facilities where the chicks were hatched and raised in controlled conditions on a standard diet. The chicks were closely tracked and monitored for weight gain, health and appearance. After 12 weeks, the birds were slaughtered weighed and judged for edible meat yield. In 1946 and 1947, a series of state and regional contests took place and from them 40 finalists were chosen to compete for the national title of Chicken of Tomorrow. In 1948, and again in 1951, Arbor Acres White Rocks won in the purebred category. The white feathered Arbor Acres birds were preferred to the higher preforming dark feathered Red Cornish crosses from the Vantress Hatchery. Eventually the two breeds were crossed to become the Arbor Acre breed that came to dominate the genetic stock of chicken worldwide.

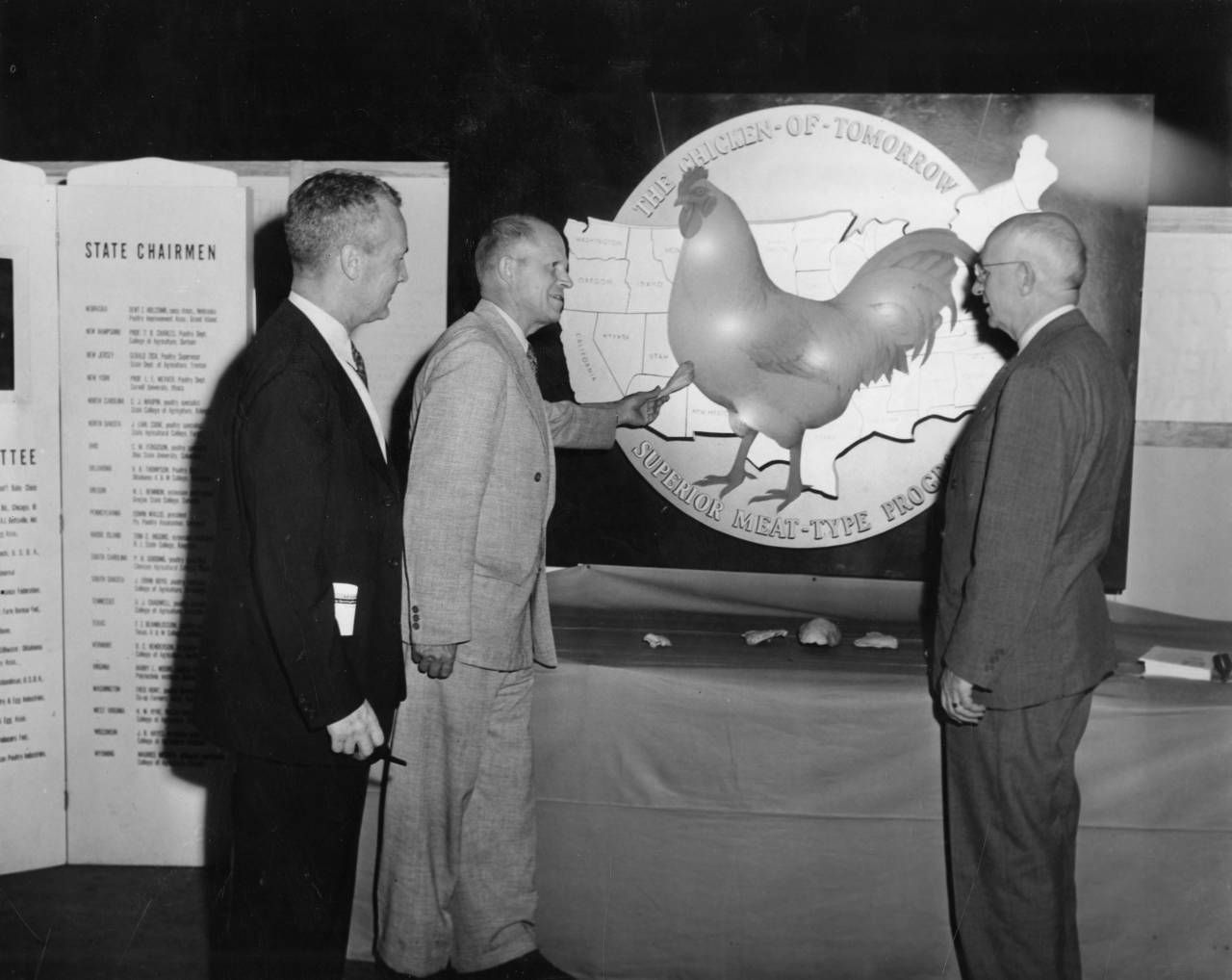

Dr. Schrader illustrating the idea of “The Chicken of Tomorrow” Via

Arbor Acres was run by Franks Saglio, an Italian immigrant who grew fruits and vegetables in Glastonbury, Connecticut on a small family farm. His son, Henry, started raising chickens for local sales. It was Henry’s birds that eventually won the Chicken of Tomorrow contest, from which the family went on to build a national breeding business which sent parent stock to all the major broiler companies in the country. In addition to supplying Arbor Acres breeding stock, the company also developed techniques and facilities to promote the best performance of the birds. Driven by processors’ demands for more and cheaper chicken, the broiler industry went through a rapid vertical integration process with hatcheries, growers, feed mills and processors all merged into larger and larger commercial farms. The Saglio family helped found the National Chicken Council, the chicken industry’s public relations and lobbying organization.

Here is where the story takes a big turn. In 1964, Nelson Rockefeller bought Arbor Acres and took it global through his company, International Basic Economy Corporation (IBEC).

Nelson Rockefeller left government service the same year A&P held the first Chicken of Tomorrow contest, and in 1947 set up two new organizations to demonstrate his alternative approach to President Truman’s Point IV Program for technical assistance to developing countries. The American International Association for Economic and Social Development (AIA) was Rockefeller’s policy arm and IBEC was the business arm. Called by some the Rich Neighbor Policy, Rockefeller’s private development companies initially brought U.S. capital and technology to places like Brazil and Venezuela to jump start modern consumer capitalism. IBEC began with $3 million from Nelson Rockefeller, and $21 million from Standard Oil. IBEC’s investments included poultry production, supermarkets, housing, agribusiness and textiles.

In addition to demonstrating that U.S. capital and American know-how could create a thriving middle class in places ruled by autocrats and populated by the poor and illiterate, IBEC had a Cold War agenda as well. As Nelson Rockefeller was known to say, “it’s hard to be a Communist with a full belly.” Many of IBEC’s operations were located in countries where Standard Oil was pumping oil and nationalist and peasant uprisings were occurring.

From the John E. Weidlich Collection at USDA

IBEC’s model undercut peasant production of food, replacing it with a capital-intensive system. To make this system work required, on the production side, a steady supply of feed grain, and on the consumer-side, a way to distribute and sell the meat that looked more like A&P than traditional open air markets and bodegas. In 1949, IBEC formed a joint venture with Cargill to build grain elevators in Argentina. Cargill had been hoping to enter the Latin American market and the IBEC partnership opened the door, first in Argentina and then in Venezuela and Brazil. Today, Cargill has over $8 billion invested in Latin America and 25,000 employees. By 1956, according to an IBEC consultant reporting on supermarcados in Venezuela, it could “truthfully be said that the modern supermarkets are displacing the old fashioned ‘bodegas.’” (In 1969, 14 of the 17 IBEC supermarkets in Buenos Aires were burnt to the ground by nationalists when Nelson Rockefeller came to visit.)

John E. Weidlich Collection (via USDA)

With IBEC’s purchase of Arbor Acres, the AA genetic stock—as it is known in the trade—went global, starting in Latin America and moving quickly to Africa, Asia and Europe. In Asia, one IBEC employee, John Rogers, founder of Rogers Enterprise International, setup Arbor Acres joint ventures with leading agribusiness companies, including Charoen Pokphand Foods with operations in Thailand, Taiwan, Indonesia and India; the San Miguel Corporation in the Philippines; and Mitsui and Co. in Japan. Still today, 50 percent of the chicken raised in China comes from the Arbor Acres genetic stock.

Not all of IBEC’s development projects were as successful as Arbor Acres, and by the 1970s IBEC started to divest of it holdings. In 1980, when it merged with Booker McConnell Limited of Great Britain, IBEC changed its name to Arbor Acres. Since then, Arbor Acres has changed hands several times and is currently owned by Avigen, a chicken breeder selling three brands of chicken—Arbor Acres, Ross and Indian River in 130 countries worldwide.

John E. Weidlich Collection at USDA

What do you get when you combine a family farm, a supermarket contest and a global corporation? It is a bad joke, and even more, it misses the real question we have to answer: What have we lost to the creation of industrial chicken?

Let’s start with the chickens. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) there has been a marked decline in the past half century of farm livestock breeds. “Up to 30% of global mammalian and avian livestock breeds (i.e., 1,200 to 1,500 breeds) are currently at risk of being lost and cannot be replaced.” A Purdue University study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reported that 50 percent or more of ancestral chicken breeds have been lost and that the greatest decline in chicken diversity took place in the 1950s with the introduction of industrial chicken production.

The thousands of farmers who took part in the Chicken of Tomorrow contests disappeared even more quickly than the breeds. They were replaced by ever larger chicken operations managed by farmers with little control over their farms. The remaining farmers are faced with signing bad contracts with immense transnational chicken processors that control every aspect of the process, from cage to carcass.

Despite the best efforts of the breeders to develop disease-resistant birds, the combination of chickens bred to gain weight and muscle rapidly, plus living in very confined cages, has led to sicker birds requiring more and more antibiotics. The declining diversity of breeds has also contributed to less resistance to disease. The use of antibiotics to keep battery-raised chickens healthy has contributed to widespread bacterial resistance to antibiotics, creating a public health crisis.

When Henry Saglio died in 2003, according to his New York Times obituary, he was the “father” of the poultry industry. In 2000, Henry formed a new company called Pureline Genetics because of his growing concerned about the use of antibiotics in chicken production. Pureline’s drug-free breeds couldn’t penetrate the market, and by 2009 was sold to Centurion Poultry in Lexington, Georgia.

We are still eating the Chicken of Tomorrow, but it is time for a new contest, a contest not for a new Chicken of Tomorrow, but rather for a new kind of agriculture, one that is less focused on corporate profits and more focused on producing strong healthy farms and food.

The quest to find the Chicken of Tomorrow continues. In 2016, the Financial Times looked at eggs genetically modified at Scotland’s Roslin Institute (that’s where a sheep named Dolly, the world’s first cloned mammal, was given life) and mused “Are these the chickens of the future?” The scientist behind the GM chicks voiced her dream, “Our ultimate goal is to improve the chicken, and to improve the lot of the chicken.” And they need helping. The Royal Veterinary College says selective breeding has created a top-heavy bird. Broiler chickens, for example, “are subject to a range of health problems that are related to rapid growth rates and high body mass. Not only are these problems a significant welfare issue but consequently represent an economic cost to industry.”

Mankind’s quest for The Chicken of Tomorrow continues.

And now for the film.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.