“Everything can happen, everything is possible and probable. Time and place do not exist; on an insignificant basis of reality the imagination spins, weaving new patterns; a mixture of memories, experiences, free fancies, incongruities and improvisations.”

— August Strindberg (A Dream Play)

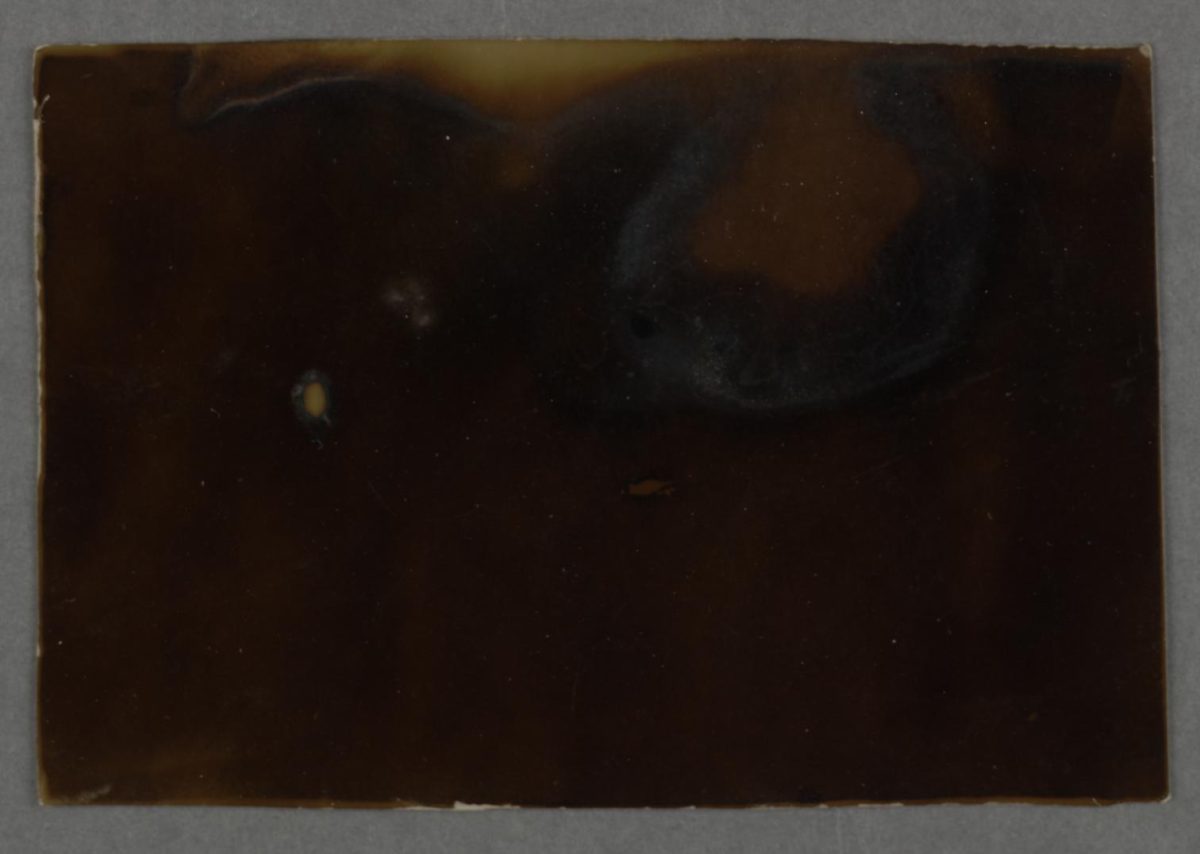

In the 1890s, Swedish playwright August Strindberg (22 January 1849 – 14 May 1912) photographed the night sky in Dornbach, Austria without a camera or lens (“sans appareil ni lentille”, as he put it in a letter to French astronomer and author Camille Flammarion). Strindberg called his curious pictures celestographs.

But what was it he captured on those glass plates placed on the ground beneath the night sky? It’s open to interpretation.

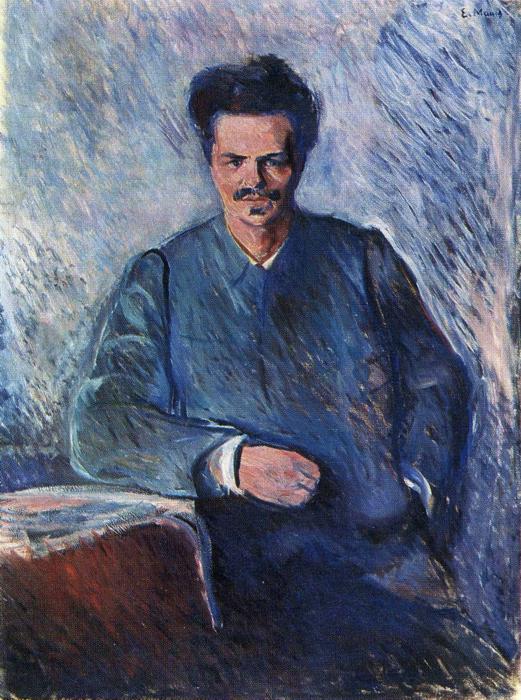

August Strindberg

“Strindberg distrusted camera lenses, since he considered them to give a distorted representation of reality. Over the years he built several simple lens-less cameras made from cigar boxes or similar containers with a cardboard front in which he had used a needle to prick a minute hole. But the celestographs were produced by an even more direct method using neither lens nor camera. The experiments involved quite simply placing his photographic plates on a window sill or perhaps directly on the ground (sometimes, he tells us, already lying in the developing bath) and letting them be exposed to the starry sky.”

-Douglas Feuk in 2001 Cabinet magazine

Strindberg wanted to see and reveal universal truths. A friend of the painter Edvard Munch, Stindberg expressed his search in the 1884 essay “chance in artistic creation”. What we see is not fixed. Art emerges from doing. Pick up the pen, brush or camera and see what develops. Chance should be allowed to play a role in artistic creation. “The arts of the future (which will pass away, like everything else!) imitate nature closely; above all, imitate nature’s way of creating!”

“At first you see nothing but a chaos of colors; then it begins to look like something, it resembles — no, it does not look like anything. All of a sudden, a point detaches itself; like the nucleus of a cell, it grows, the colors are clustered around it, heaped; rays develop, shooting forth branches and twigs like ice crystals on the window panes… and the picture reveals itself to the viewer, who has assisted at the birth of the painting.”

Strinberg pinteed without a bush.

I paint in my spare time. To master my material, I select a medium-sized canvas or preferably a board, so that I am able to complete the picture in two or three hours, while my inspiration lasts.

I am possessed by a vague desire. I imagine a shaded forest interior from which you see the sea at sunset.

So: with the palette knife that I use for this purpose—I do not own any brushes!—I distribute the paints across the panel, mixing them there so as to achieve a rough sketch. The opening in the middle of the canvas represents the horizon of the sea; now the forest`s interior unfolds, the branches, the tree crowns in groups of colors, fourteen, fifteen, helter-skelter—but always in harmony. The canvas is covered. I step back and take a look!

Well, I’ll be darned! There is no sea to be seen. The illuminated opening shows an endless perspective of rose-colored, bluish light in which airy, disembodied and undefined beings float like fairies, trailing clouds behind them. The forest has turned into a dark subterranean cave, obstructed by brambles: and in the foreground—let’s see what it could be—rocks covered with lichens, the likes of which are not to be found—and there, on the right, the knife has glossed over the paint too much, so that it resembles reflections in water—well, look! It’s a pond. Wonderful!

What next? Above the water, there is a white and pink spot whose origin and significance I cannot explain. Wait a moment!—a rose—The knife goes to work for two seconds, and the pond has been framed in roses, roses, what a lot of roses!

A slight touch here and there with my fingers, blending the resisting colors, fusing and banishing any jarring tones, thinning, dissolving, and there’s the painting!

My wife, at the moment my friend, comes up to take a look, falls into ecstasy before the “Tannhäuser cave” from which the large serpent (my hovering fairies) slithers out into the wonderland; and the mallows (my roses!) are mirrored in the sulphurous spring (my pond), etc.

For a whole week she admires my “masterpiece,” values it at thousands of francs, assures me that it belongs in a museum, etc.

Eight days later we are once more in a period of hateful antipathy; she sees my masterpiece as pure garbage!

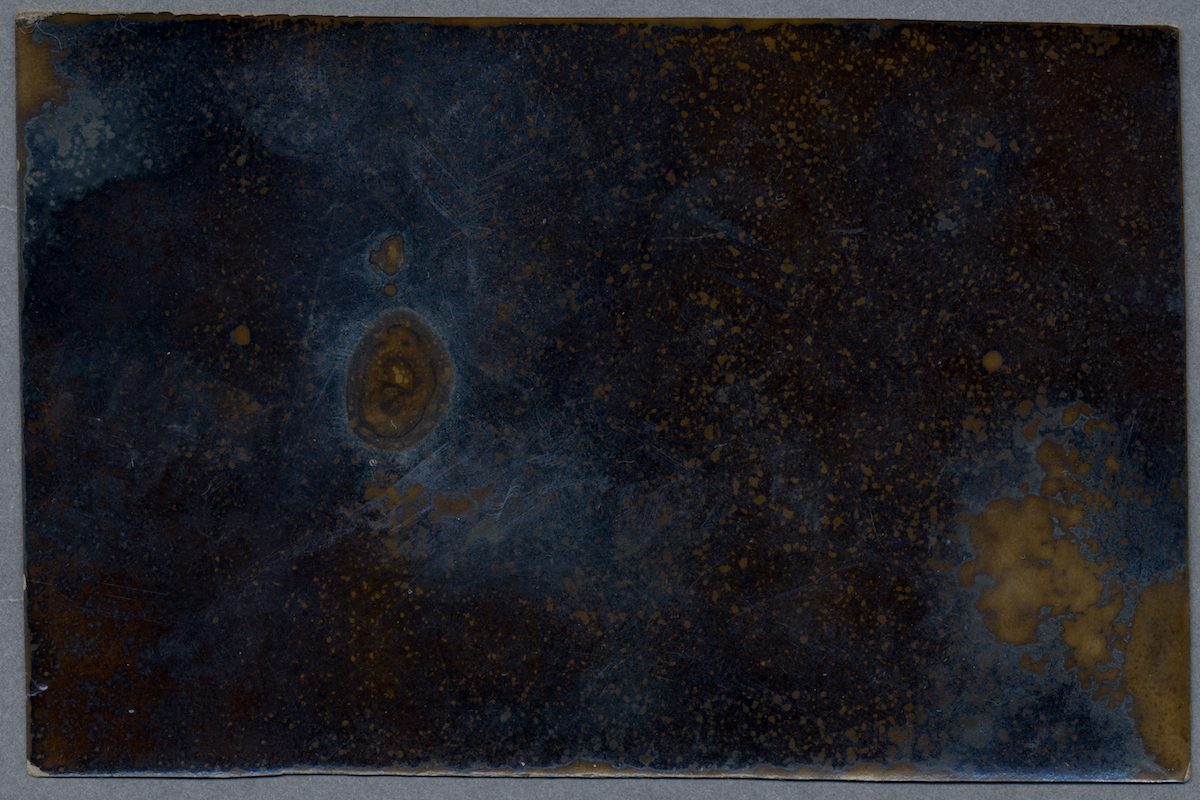

Celestograph X Date: 1893-94. Photographer: August Strindberg Photographic type: Celestograph Notes: Starry sky

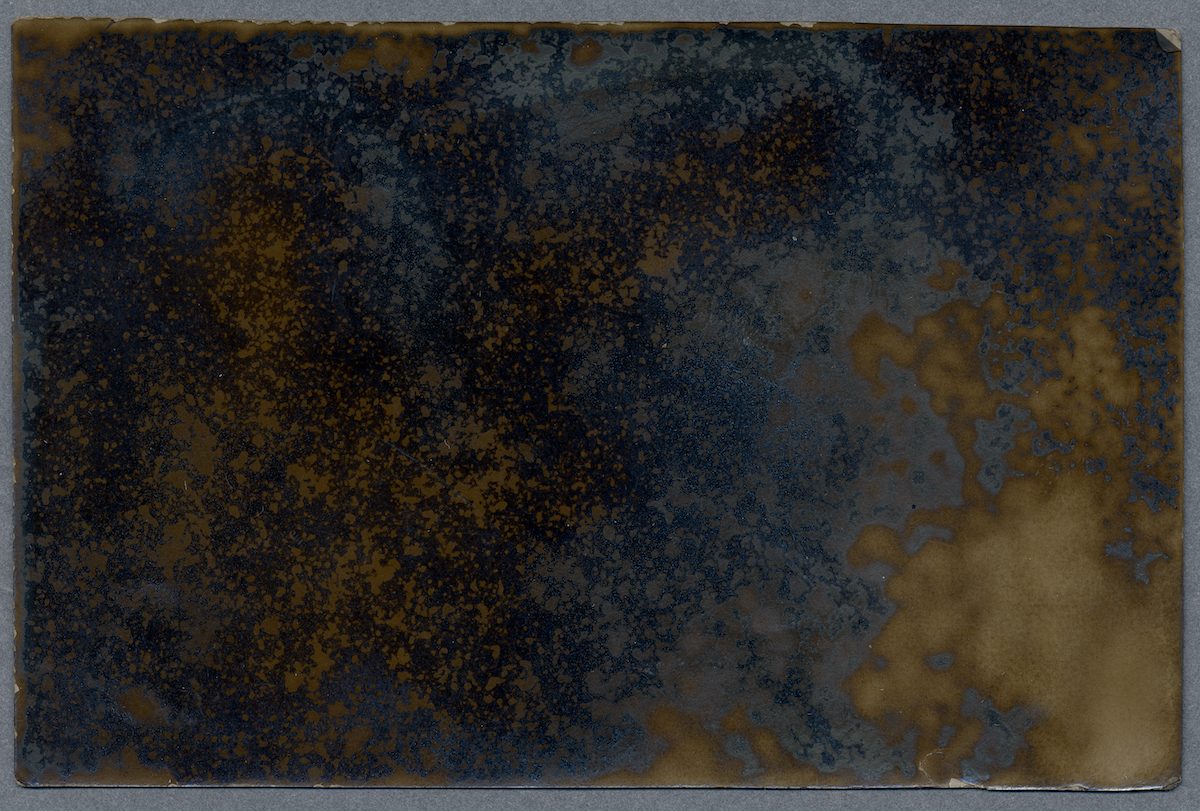

So, what are we seeing in Strinberg’s pictures, space and something invisible to the naked eye? Is everything just dust, the celestographs more chemigrams, images made by chemicals mixing with photosensitive emulsions and dust, grit and other particles? You take photographic paper, put things on it and see what happens.

“With the advent of photography in 1839 painting underwent a radical transformation,” notes Pierre Cordier. “Nowadays, the digital process is revolutionising photography. The Chemigram, fusion of painting and photography, is most likely the ultimate adventure of gelatin silver bromide.”

Celestograph IX Date: 1893-94. Photographer: August Strindberg Photographic type: Celestograph Notes: Starry sky

So, do you see? Sue Prideuax has written of Strindberg’s influence on Munch:

Strindberg knew an awful lot of artists. I’ll confine my answer to a few. Strindberg and Edvard Munch were inseparable friends during the time Munch was planning and painting the Scream. Strindberg’s then-revolutionary idea that Chance should be allowed to play a role in artistic creation loosened up Munch’s work to embrace random happenings. You can see a bird dropping on the Scream torso and the splatter-pattern of candlewax in the right-hand bottom corner that suggests Munch painted the picture at night, blew out the candle carelessly and never bothered to try to remove the wax. In Strindberg’s words, these physical traces ‘bind chance with creation in a metamorphosis surpassing Ovid’ in creating a dynamic interaction between the artwork and the real world.

Celestograph XV. Date: 1893-94. Photographer: August Strindberg. Photographic type: Celestograph

Buy Celestial wonders in the Shop.

Via: National Library of Sweden

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.