“Pacifism is objectively pro-fascist.”

– George Orwell

The British Union of Fascists (BUF), founded by Oswald Mosley in 1932, was a shining example of how fascist movements draw on local antagonisms while cozying up to movements abroad. Mosley’s Blackshirts dressed up like Mussolini’s thugs and saluted like Hitler’s, but theirs was a distinctly English program. The first of Mosley’s “10 Points of Fascism” announced that the BUF was “loyal to King and Country” and its “watch-word… is ‘Britain First.’” A primary focus of its anti-immigrant and antisemitic sentiment was Stepney, an East End neighborhood then home to 60,000 Jews descended from families who fled pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe, as well as Irish and other immigrant workers.

Most BUF members were laid-off workers during the Great Depression who fell for a program in which Mosley promised class levelling and “the triumph of the ‘new fascist man’” over immigrant workers, notes the anti-racist organisation Hope Not Hate. “Mosley attracted as many as 40,000 members in 1934 and the support of the Daily Mail, who ran the notorious headline ‘Hurrah for the Blackshirts’ in the same year.”

The BUF’s reputation in the press was also tarnished that year when Blackshirts beat anti-fascist hecklers at the notorious Olympia rally. Doubling down, and “increasingly under the influence of Hitler, BUF leaders sought to exploit the reservoir of antisemitism in the East End in order to save the party.”

By 1936 the BUF was pouring most of its resources into holding meetings in the East End and distributing crude antisemitica. Mob orators such as Mick Clarke and Owen Burke sought to whip up violence on street corners night after night.

As this approach gradually gained support in poor neighbouring areas such as Bethnal Green, Mosley announced he would celebrate the fourth birthday of the BUF by staging a provocative march through Stepney, the heart of the Jewish East End, on 4 October, 1936.

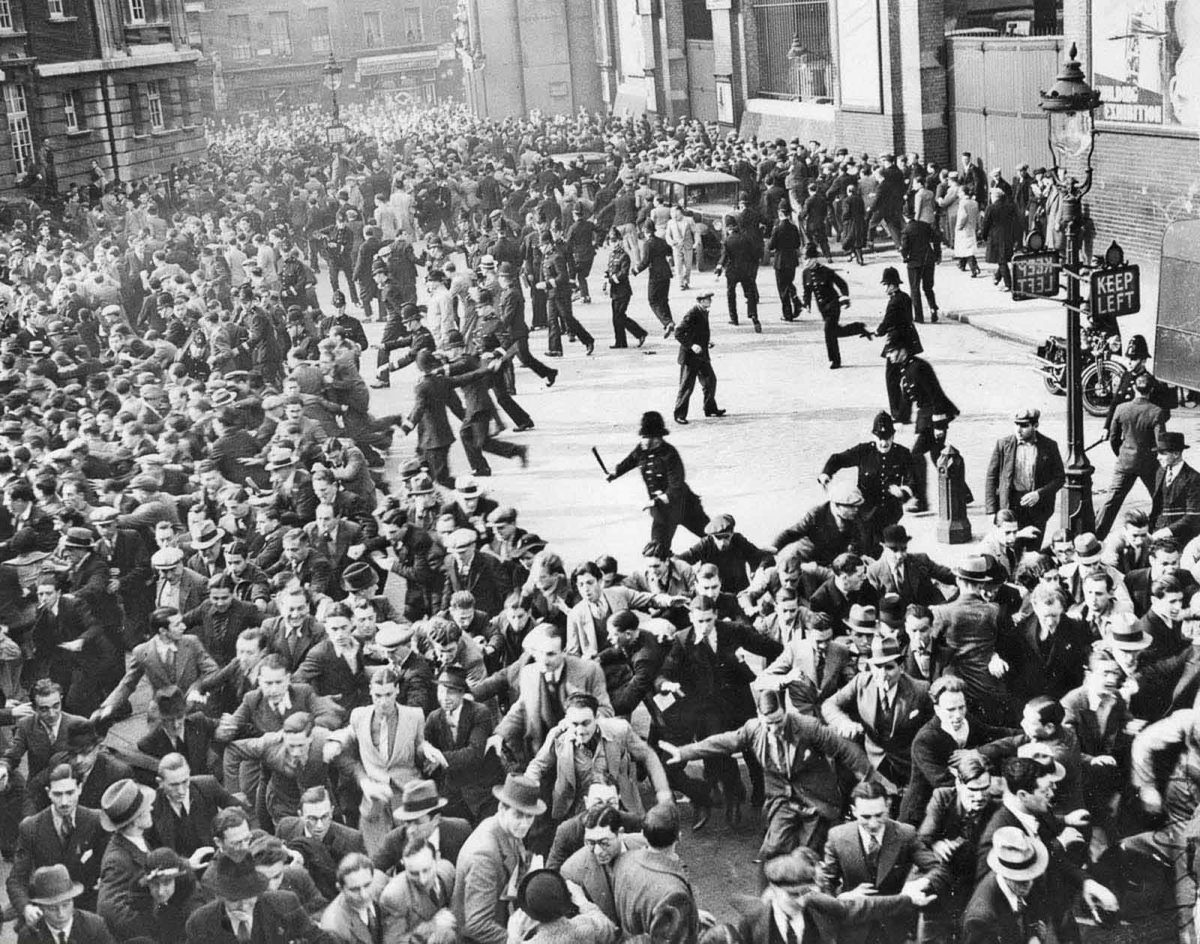

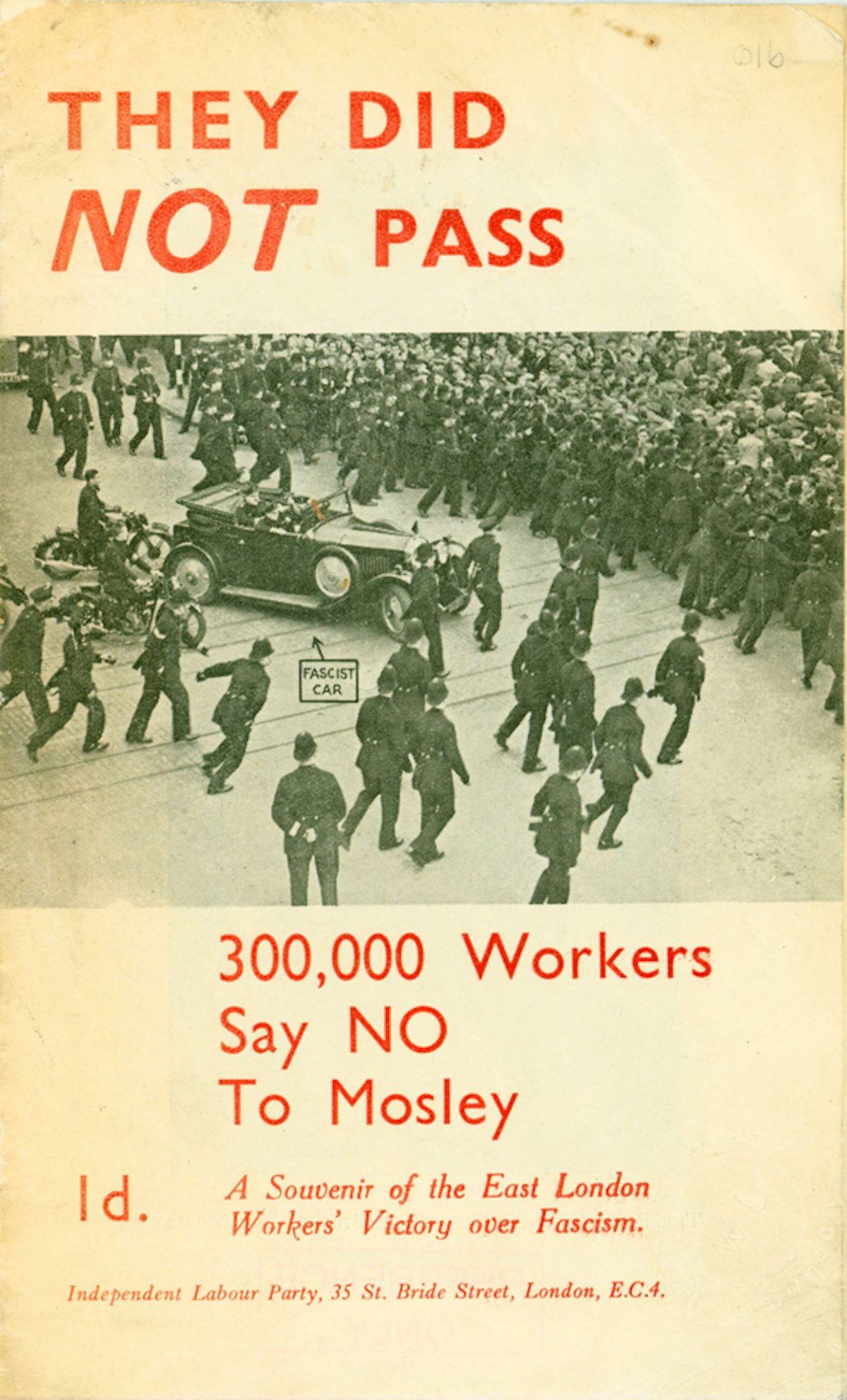

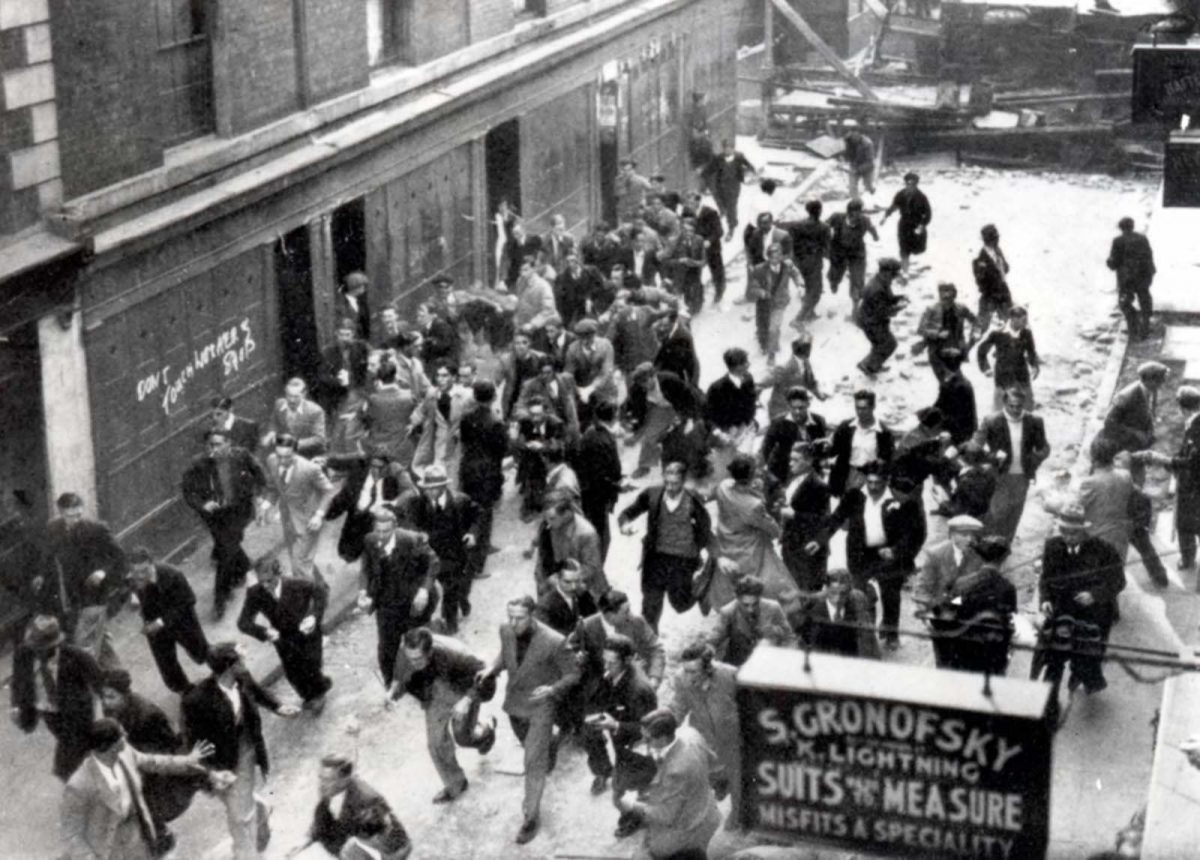

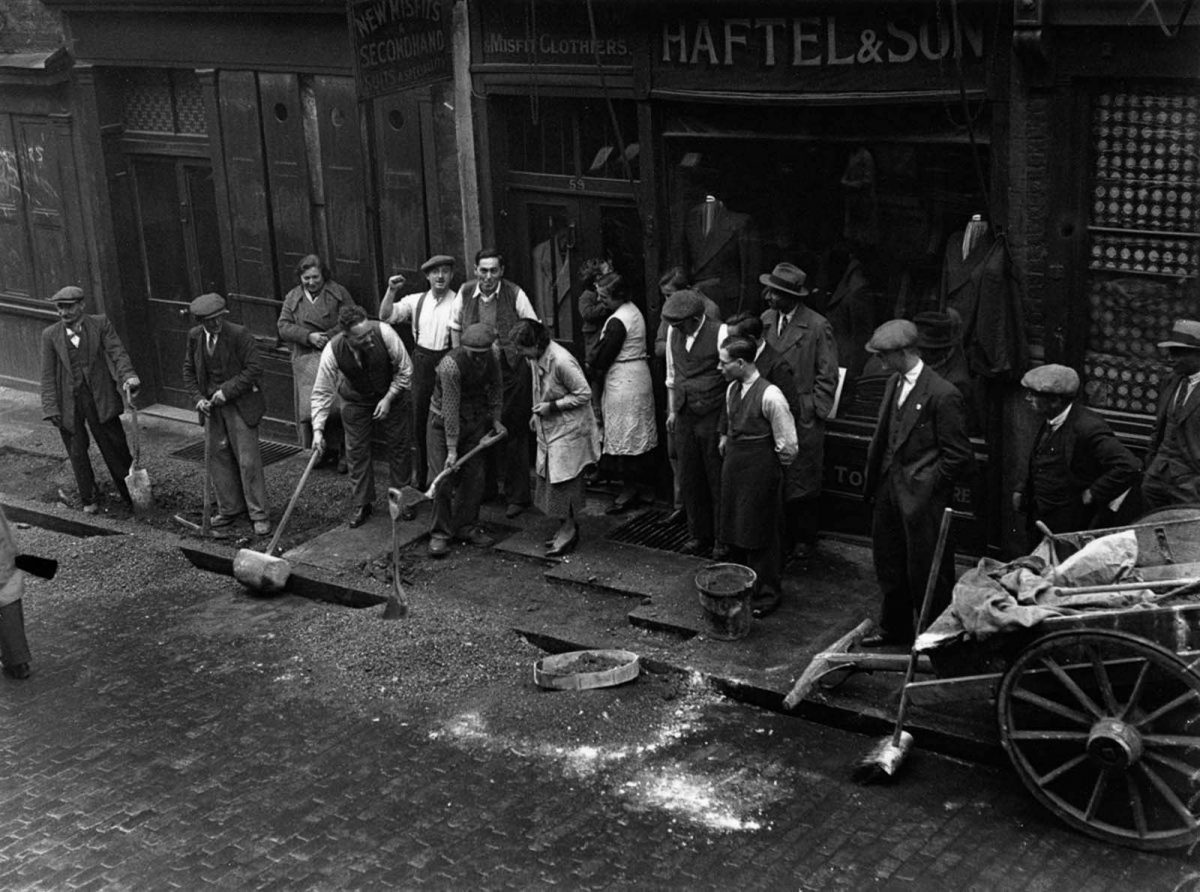

BUF organizing led to what became known afterward as the “Battle of Cable Street,” in which tens of thousands of anti-fascists and regular Londoners battled 6,000 police and 3,000 BUF Blackshirts to refuse the fascists passage through Stepney. Taking their example from Spanish Communists during the siege of Madrid months earlier, they used as their slogan “¡No pasarán” and erected three sets of barricades on Cable Street. Irish dockworkers tore up paving stones and filled the street with broken glass and marbles to defeat mounted police.

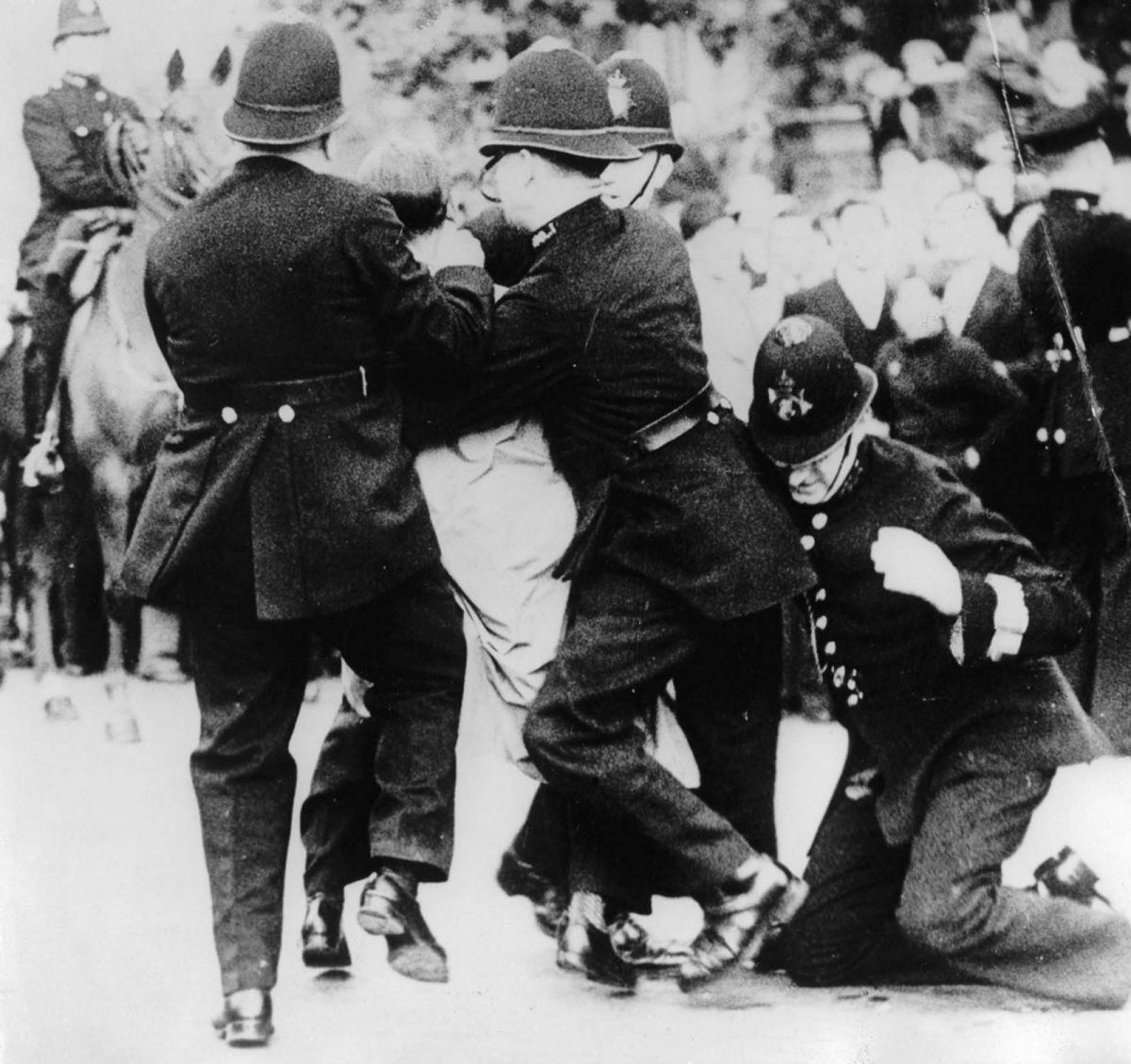

Every history of the Battle of Cable Street must acknowledge that the primary antagonists were not in fact the BUF, but the police, who showed up in overwhelming numbers to protect the fascists. Police evinced sympathy for Mosley’s Blackshirts in the “heavy-handedness toward Jewish men and boys in the crowds,” notes the International Centre for the History of Crime. Then, as now, they “concerned themselves with threats from the Left to public order” and brutally attacked the crowd of around 20,000, ignoring the violence of the BUF. “They acted with the full support of many others in authority,” arresting around 150 anti-fascists.

Historian Mark Bray, in his Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook, offers the Battle of Cable Street, as “a potent symbol,” writes Daniel Penny at The New Yorker, “of how to stop Fascism: a strong, unified coalition outnumbered and humiliated Fascists to such an extent that their movement fizzled.” This, at least, is the popular narrative. The march may have fizzled, but “the Battle of Cable Street was not the great victory over British fascism as left mythologizers portrayed it,” Anshel Pfeffer argues at Haaretz. “Membership in the BUF in London nearly doubled afterwards and a week later 200 black-shirts attacked Jews and burnt shops not far from Cable Street in what became known as the ‘Mile End Pogrom.’”

But while the far-right continued to draft some of England’s workers against others, paving the way for the National Front, they would not gain the same foothold in England at the time as their heroes on the continent. And while Labour, Communist Party, and Jewish leaders would later claim the victory as their own, almost all opposed organizing against the BUF in Stepney at the time, planning counter marches in Trafalgar Square, for example. The many thousands of trade unionist, socialists, anarchists, communists, and ordinary Londoners who gathered against fascism that day ignored leaders on the left who told them to stay away, and turned out to protest not only the BUF, but a government that allowed the march to go forward.

Resisting fascism was “the major thing in the life of most active political people in East London, says eyewitness Lou Kenton in a British Library oral history project. “It arose naturally that you were either Labour or communist, and there was never a very sharp division, certainly not in my mind.” As for the Battle of Cable Street, says Kenton, it “had to be a non-Jewish thing,” a show of immigrant solidarity, working-class unity, and “a certain togetherness, of warmth.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.