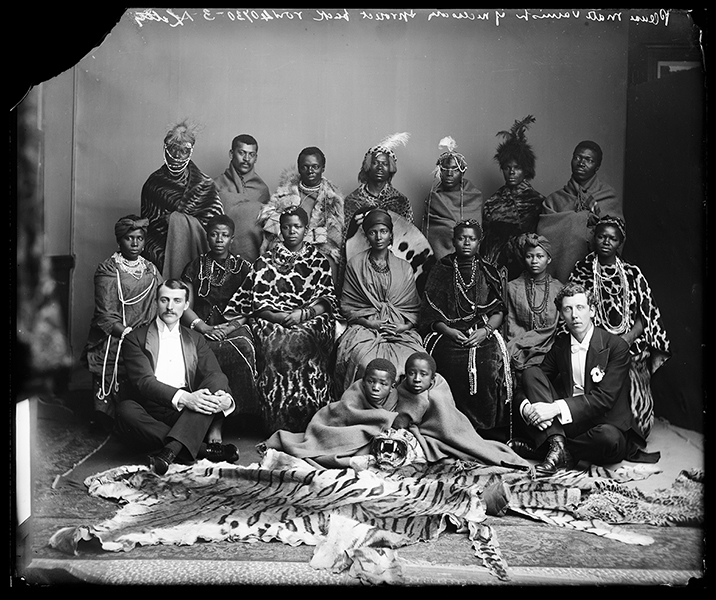

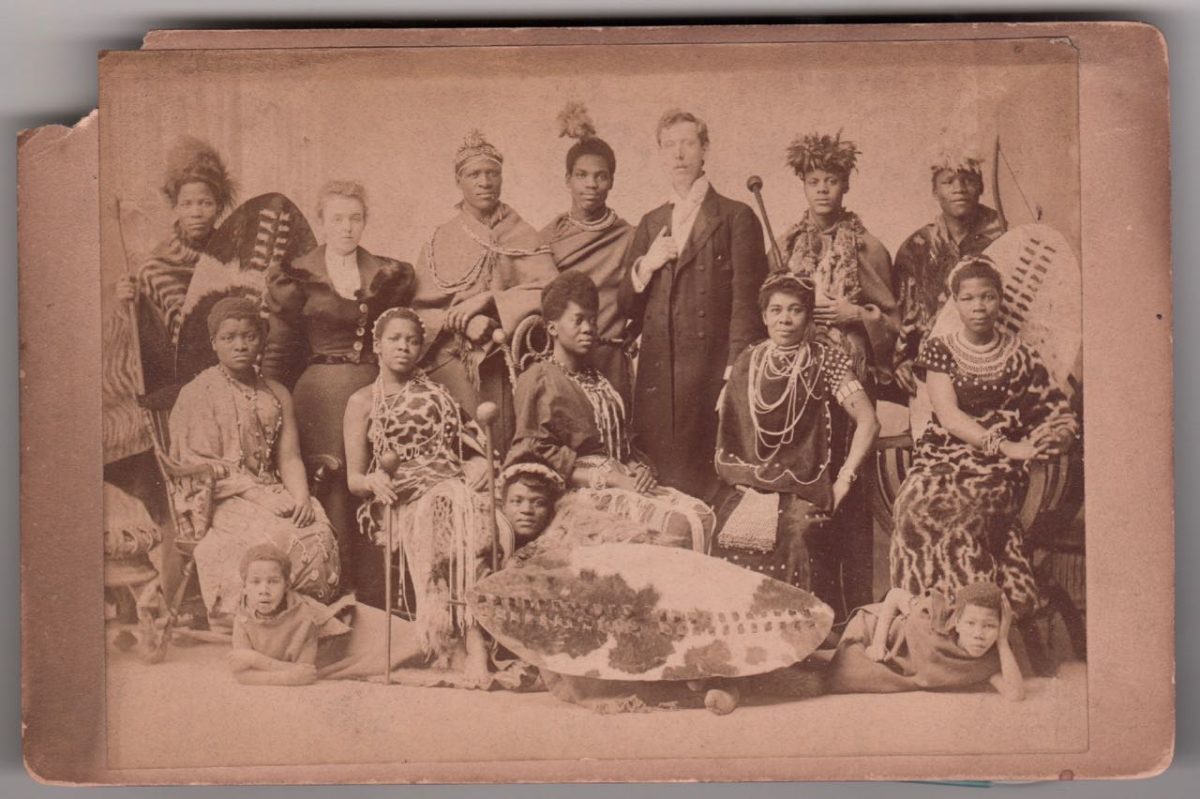

Between 1891 and 1893, 14 young men and women, and two children, from South Africa, then under British rule, toured the United Kingdom as the African Choir.

The toured was intended to raise funds to build a technical college on the Cape Coast, in order to support the expanding black labour force. They were educated, Christians, many graduates from Lovedale College, a missionary school established by the Glasgow Missionary Society in the Eastern Cape Province.

According to newspaper reports about the choir’s performances, a speech was usually made about the tour and its fundraising aims. The speech was given by the Manager or the Musical Director, both were of white European background.

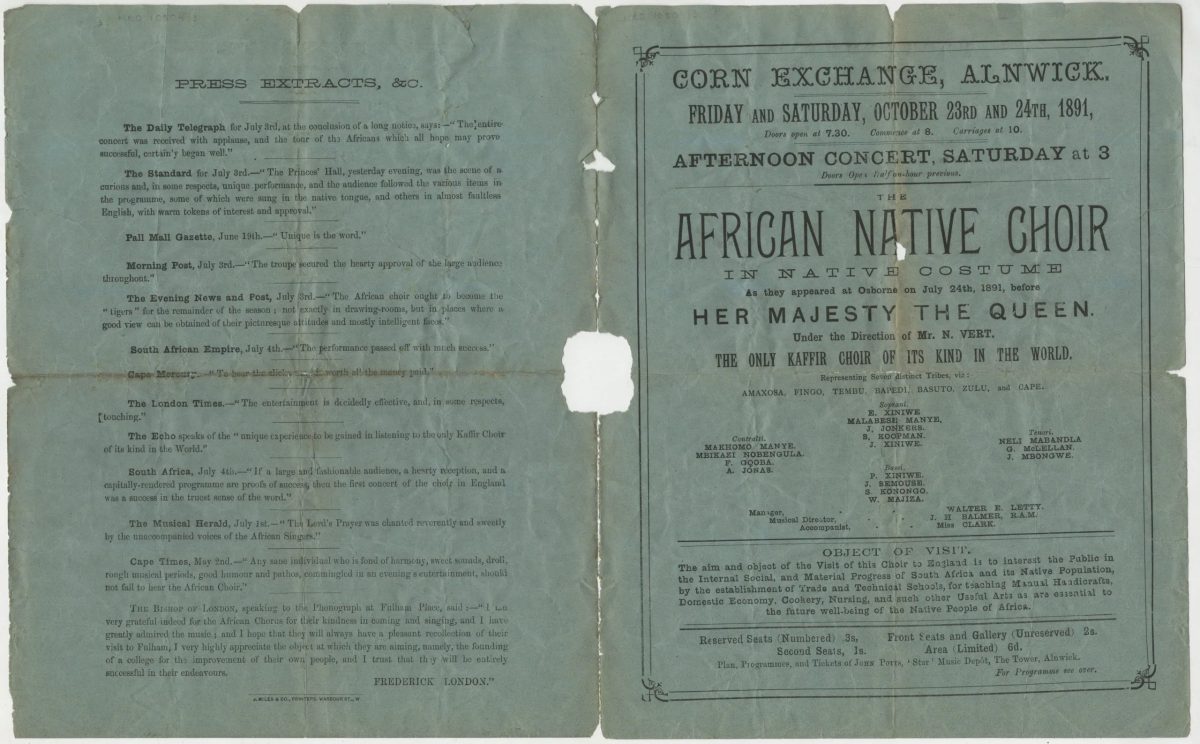

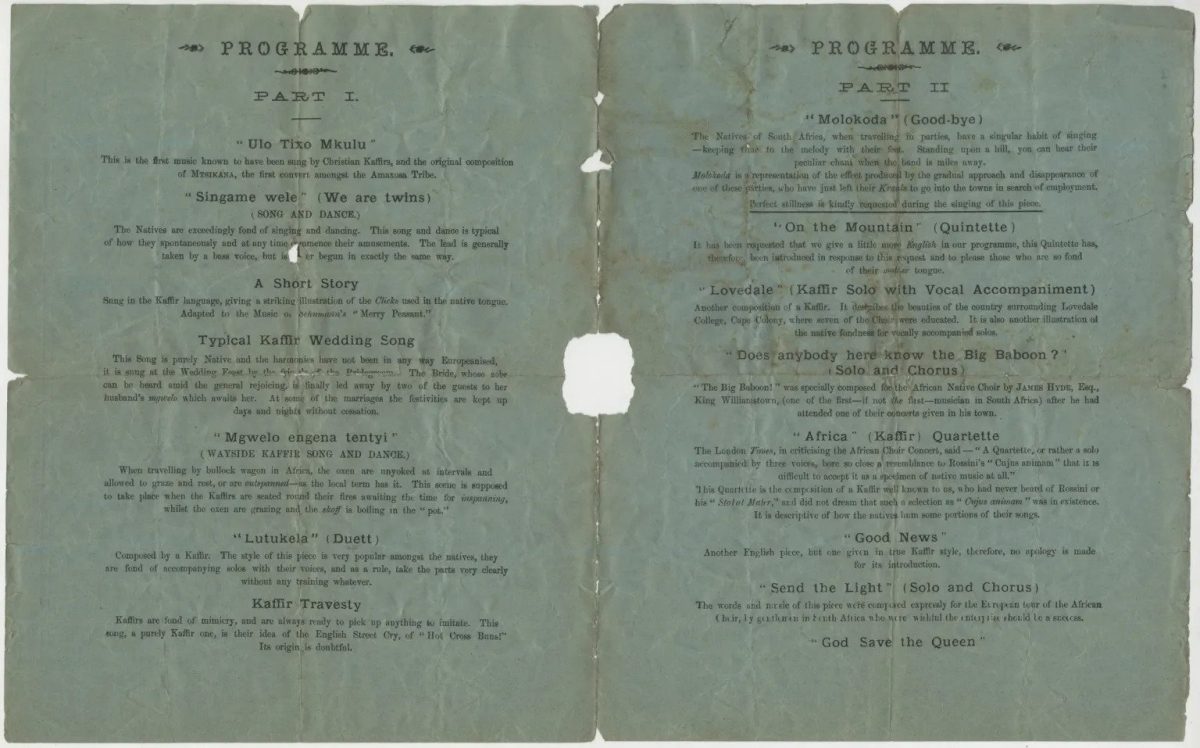

The African Choir Programme via Northumberland Archives

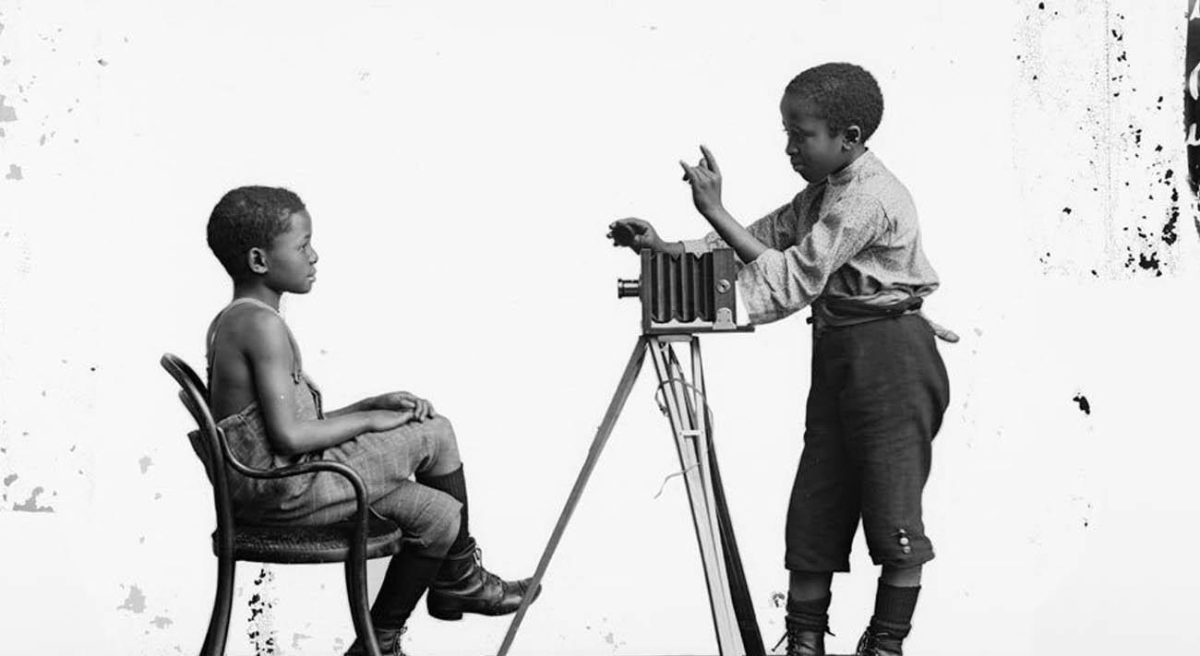

Early in the tour they performed for Queen Victoria at Osbourne House on the Isle of Wight and before large audiences at London’s Crystal Palace. A series of photographs were taken of the tour by the London Stereoscopic Company

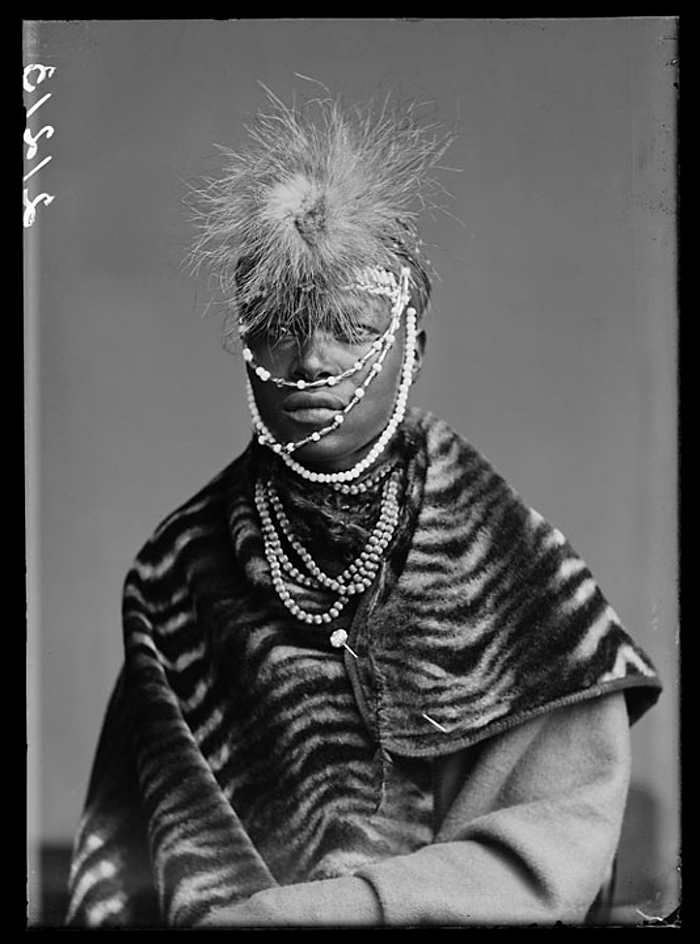

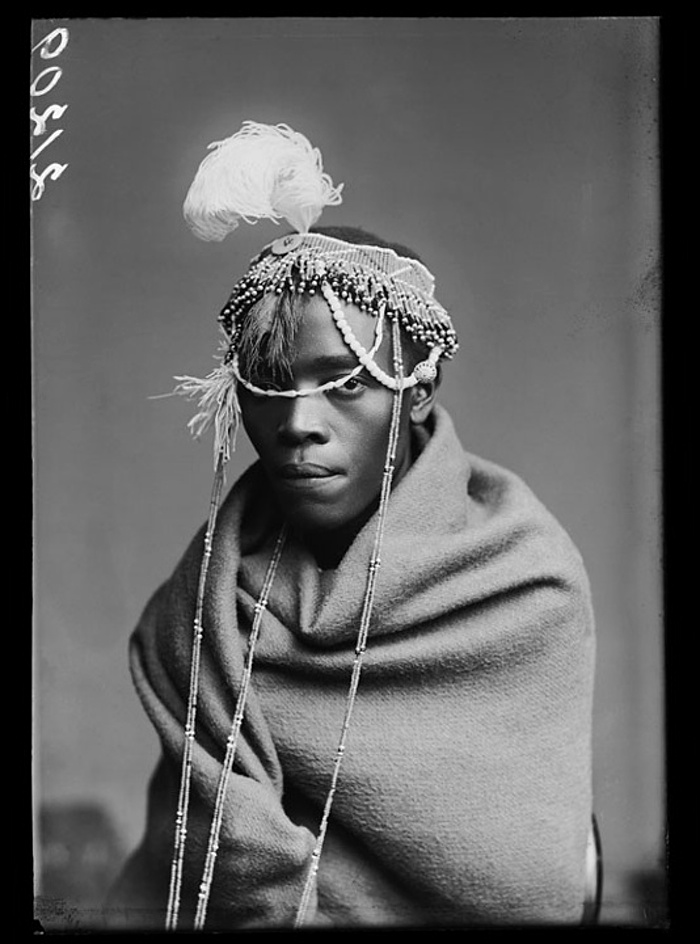

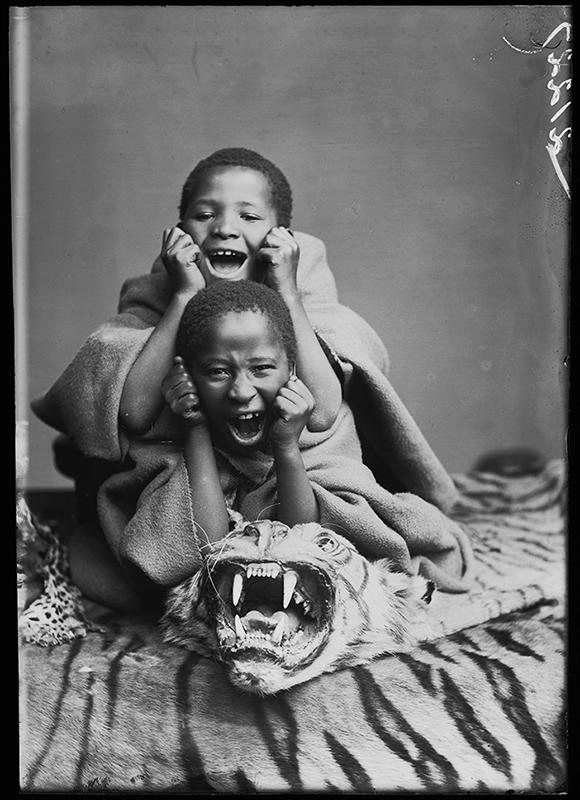

According to the MThe Missing Chapter, their stage repertoire was divided into two: one comprised Christian hymns sung in English together with popular operatic arias and choruses; the other traditional African hymns. The choir appeared in traditional African dress, hamming it up with Indian tiger skins and anything else the crowd might deem exotic, and in contemporary Victorian dress.

Choir members such as Charlotte Maxeke (née Manye) and Paul Xiniwe later became leading social activists and reformers in South Africa.

The singers were Frances Gqoba, Albert Jonas, Johanna Jonkers, Samuel Konongo, Sannie Koopman, Neli Mabandla, Wellington Majiza, Charlotte Manye, Katie Manye, John Mbongwe, George McLellan, Mbikazi Nobengula, Josiah Semouse, Eleanor Xiniwe, John Xiniwe and Paul Xiniwe.

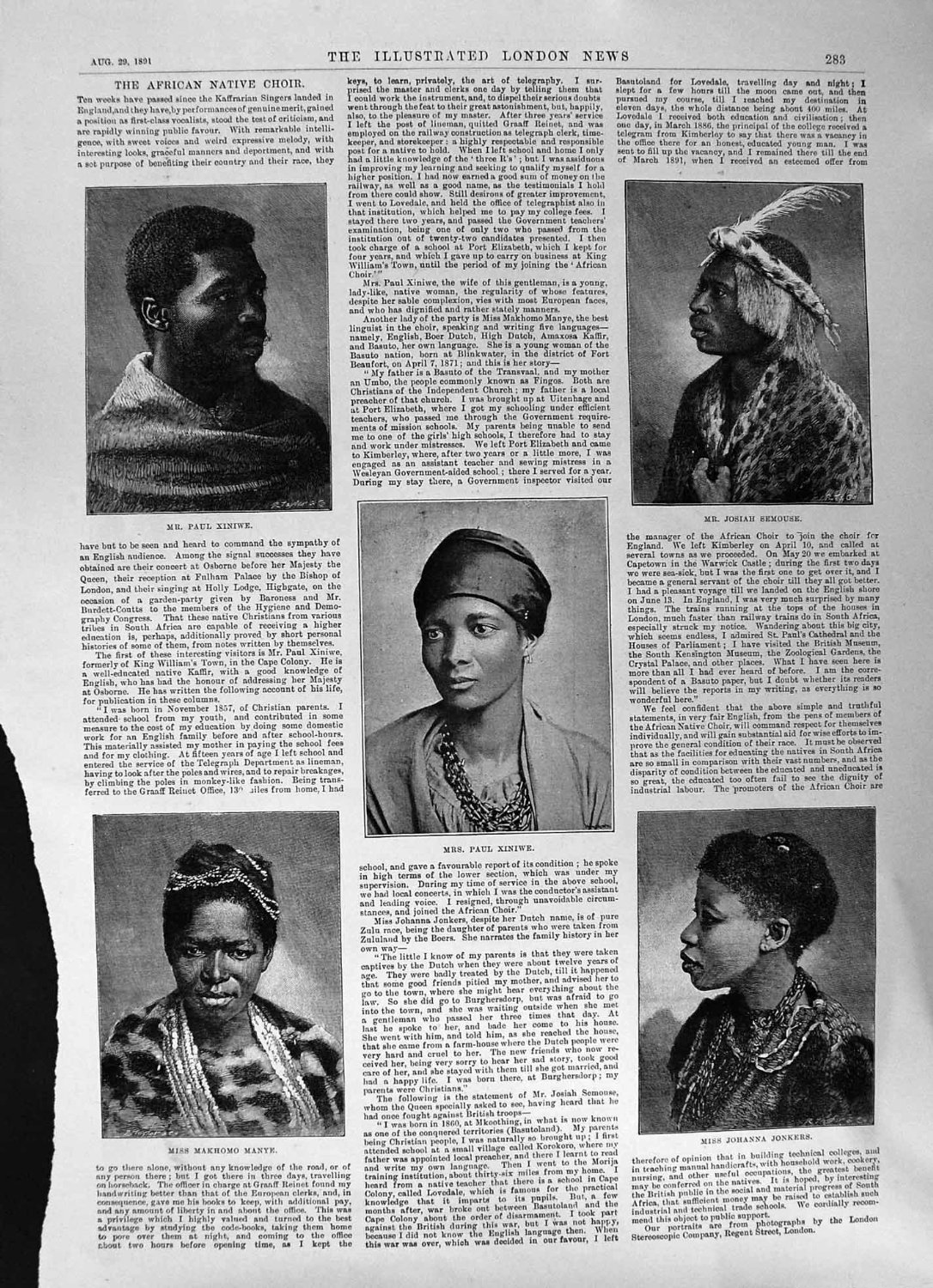

Interviewed by the Illustrated London News, some of the singers’ words appeared in the paper on 29 August 1891.

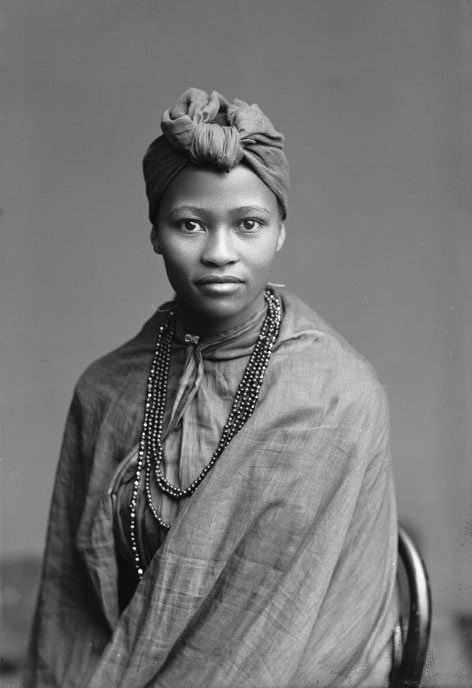

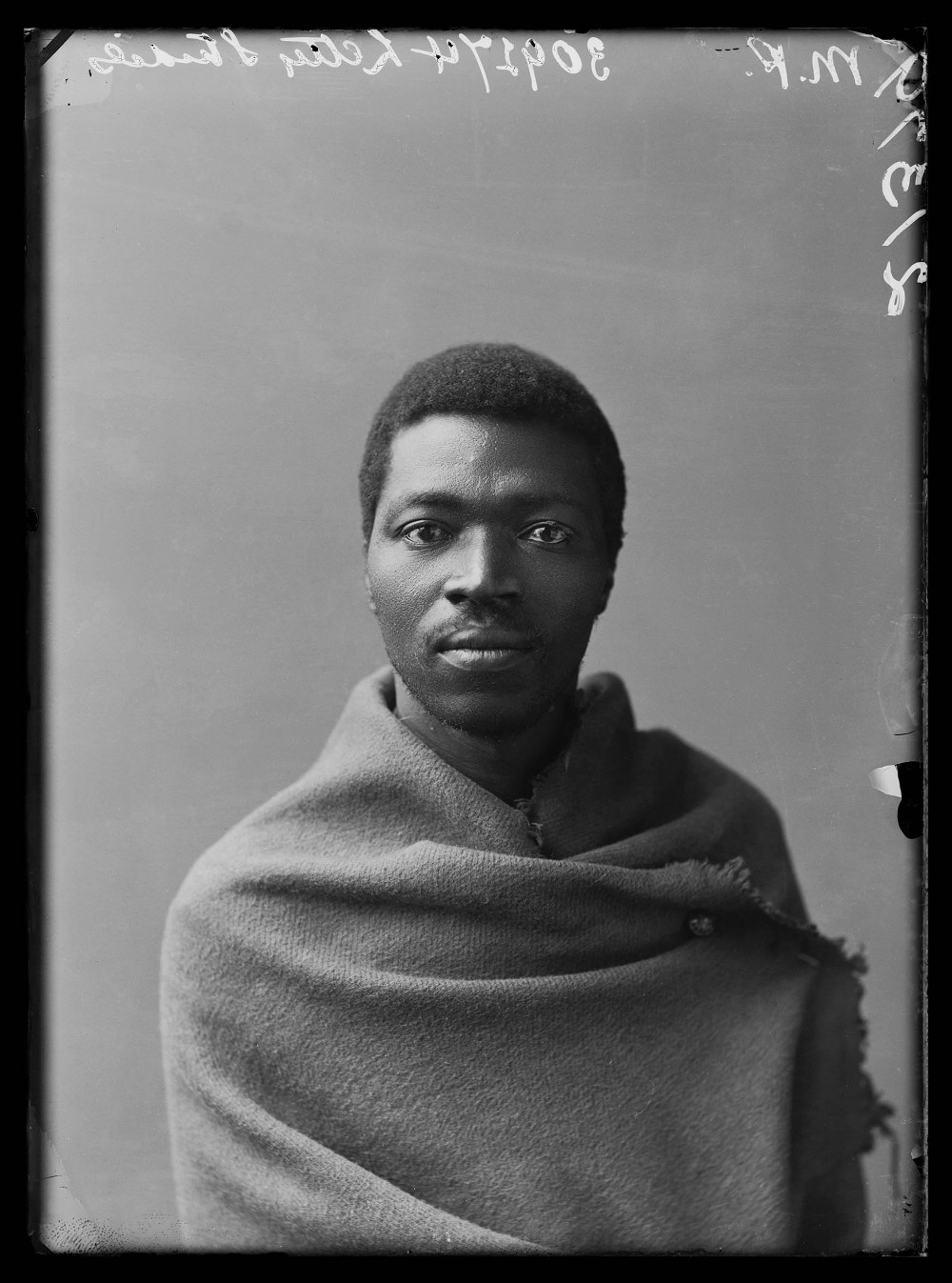

Paul Xiniwe

I was born in November 1857, of Christian parents. I attended school from my youth and contributed in some measure to the cost of my education by doing some domestic work for an English family before and after school hours. This materially assisted my mother in paying the school fees and for my clothing.

At fifteen years of age I left school and entered the service of the Telegraph Department as a lineman having to look after the poles and wires, and to repair breakages by climbing poles in monkey-like fashion. Being transferred to the Graaff Reinet Office, 130 miles from home, I had to go there alone without any knowledge of the road, or of any person there; but I got there in three days, travelling on horseback.

The officer in charge at Graaff Reinet found my handwriting better than that of the European clerks, and, in consequence, gave me his books to keep, with additional pay, and any amount of liberty in and about the office. This was a privilege which I highly valued and turned to the best advantage by studying the code-book, taking them home to pore over them at night, and coming to the office about two hours before opening time, as I kept the keys, to learn, privately, the art of telegraphy. I surprised the mater and clerks one day by telling them that I could work the instrument, and to dispel their serios bouts went through the feat to their great astonishment, but happily, also, to the pleasure of my master.

After three years’ service I left the post of lineman, quitted Graaff Reinet, and was employed on the railway construction as telegraph clerk, timekeeper and storekeeper: a highly respectable and responsible post of a native to hold. When I left school and home I only had a little knowledge of the “three Rs”; but I was assiduous in improving my learning and seeking to qualify myself for a higher position. I had now, earned a good sum of money on the railway, as well as a good name, as the testimonials I hold from there could show.

Still desirous of greater improvement, I went to Lovedale, and held the office of telegraphist also in that institution, which helped me to pay my college fees. I stayed there two years, and passed the Government teachers’ examination, being one of only two who passed from the institution out of twenty-two candidates presented. I then took charge of a school at Port Elizabeth, which I kept for four years, and which I gave up to carry on business at King William’s Town, until the period of my joining the “African Choir”.

Paul Xiniwe, The African Choir. London, 1891.

Makhomo Manye (born 7 April 1871)

My father is a Basuto of the Traansvaal, and my mother an Umbo, the people commonly known as Fingos. Both are Christians of the Independent Church; my father is a local preacher of that church. I was brought up at Uitenhage and at Port Elizabeth, where I got my schooling under efficient teachers, who passed me through the Government requirements of mission schools. My parents being unable to send me to one of the girls’ high school, I therefore had to stay and work under mistresses.

We left Port Elizabeth and came to Kimberley, where after two years or a little more, I was engaged as an assistant teacher and sewing mistress in a Wesleyan Government-aided school; there I served for a year. During my stay there, a Government Inspector visited our school and gave a favourable report of its condition; he spoke in high terms of the lower section, which was under my supervision. During my time of service in the above school, we had local concerts, in which I was the conductor’s assistance and leading voice. I resigned, through unavoidable circumstances, and joined the African Choir.”

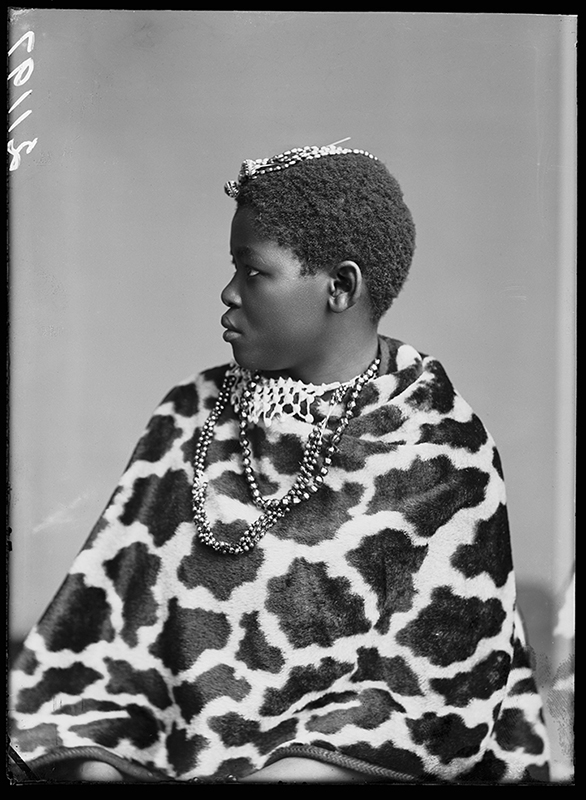

Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe of the African Choir

Johanna Jonkers

The little I know of my parents is that they were taken captives by the Dutch which they were about twelve years of age. They were badly treated by the Dutch, till it happened that some good friends pitied my mother, and advised her to go to the town, and she was waiting outside when she met a gentleman who passed her three times that day. At last he spoke with her, and bade her come to his house. She went with him, and told him, as she reached the house, that she came from a farm-house where the Dutch people were very hard and cruel to her. The new friends who now received her, being very sorry to hear her sad story, took good care of her, and she stayed with them till she got married and had a happy life. I was born here, at Burghersdorp; my parents were Christians.

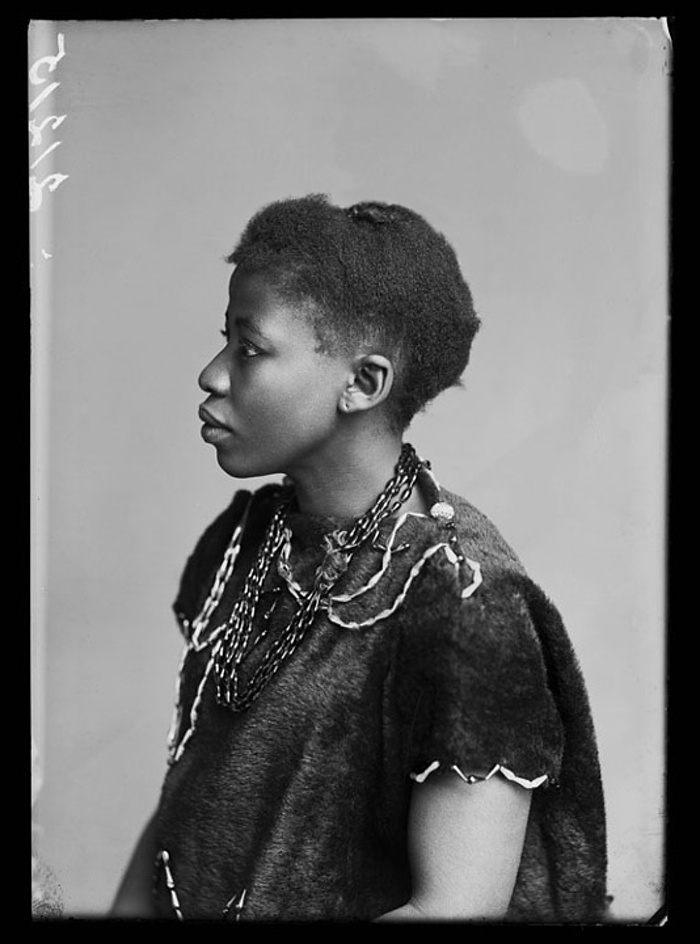

Johanna Jonkers, of the African Choir

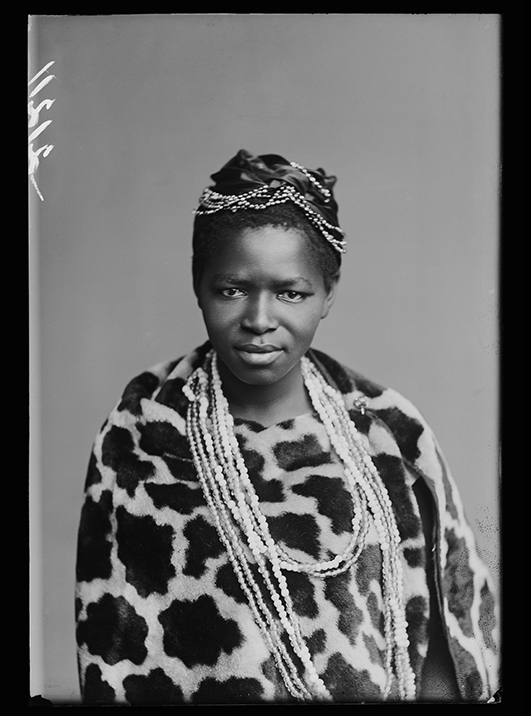

Katie Manye (1873 – 1956)

Josiah Semouse

I was born in 1860 at Mkoothing, in what is now known as one of the conquered territories (Basutoland). My parents being Christian people, I was naturally so brought up; I first attended school at a small village called Korokoro, where my father was appointed local preacher, and there I learnt to read and write my own language. Then I went to the Morija training institution, about thirty-six miles from my home. I heard from a native teacher that there is a school in Cape Colony, called Lovedale, which is famous for the practical knowledge that it imparts in its pupils. But, a few months after, war broke out between Basutoland and the Cape Colony about the order of disarmament.

I took part against the British during this war, but I was not happy, because I did not know the English language then. When the war was over, which was decided in our favour, I left Basutoland for Lovedale, travelling day and night; I slept for a few hours till the moon came out, and then pursued my course, till I reached my destination in eleven days, the whole distance being about 400 miles.

At Lovedale I received both education and civilisation; then one day, in March 1886, the principal of the college received a telegram from Kimberley to say that there was a vacancy in the office there for an honest, educated young man. I was sent to fill up the vacancy, and I remained there till the end of March 1891, when I received an esteemed offer from the manager of the African Choir to join the choir for England.

We left Kimberley on April 10, and called at several towns as we proceeded. On May 20 we embarked at Capetown in the Warwick Castle; during the first two days we were sea-sick, but I was the first one to get over it, and I became a general servant of the choir till they all got better, I had a pleasant voyage till we landed on the English shore on June 13. In England, I was very much surprised by many things. The trains running at the tops of the houses in London, much faster than railway trains to in South African, especially struck my notice.

Wandering about this big city, which seems endless, I admired St Paul’s Cathedral and the Houses of Parliament; I have visited the British Museum, the South Kensington Museums, the Zoological Gardens, the Crystal Palace, and other places. What I have see here is more than all I had every heard of before. I am the correspondent of a Basuto paper, but I doubt whether its readers will believe the reports in my writing, as everything is so wonderful here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.