As the US emerged from the Great Depression, a utopian spirit took hold, a sense that technology, design, and global cooperation would bring about “the World of Tomorrow,” as the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair advertised: a paradise of convenience and comfort. Most people could have seen war brewing on the horizon. By the Fair’s opening day, two participating countries had already been invaded. But few might have predicted just how much devastation was to come.

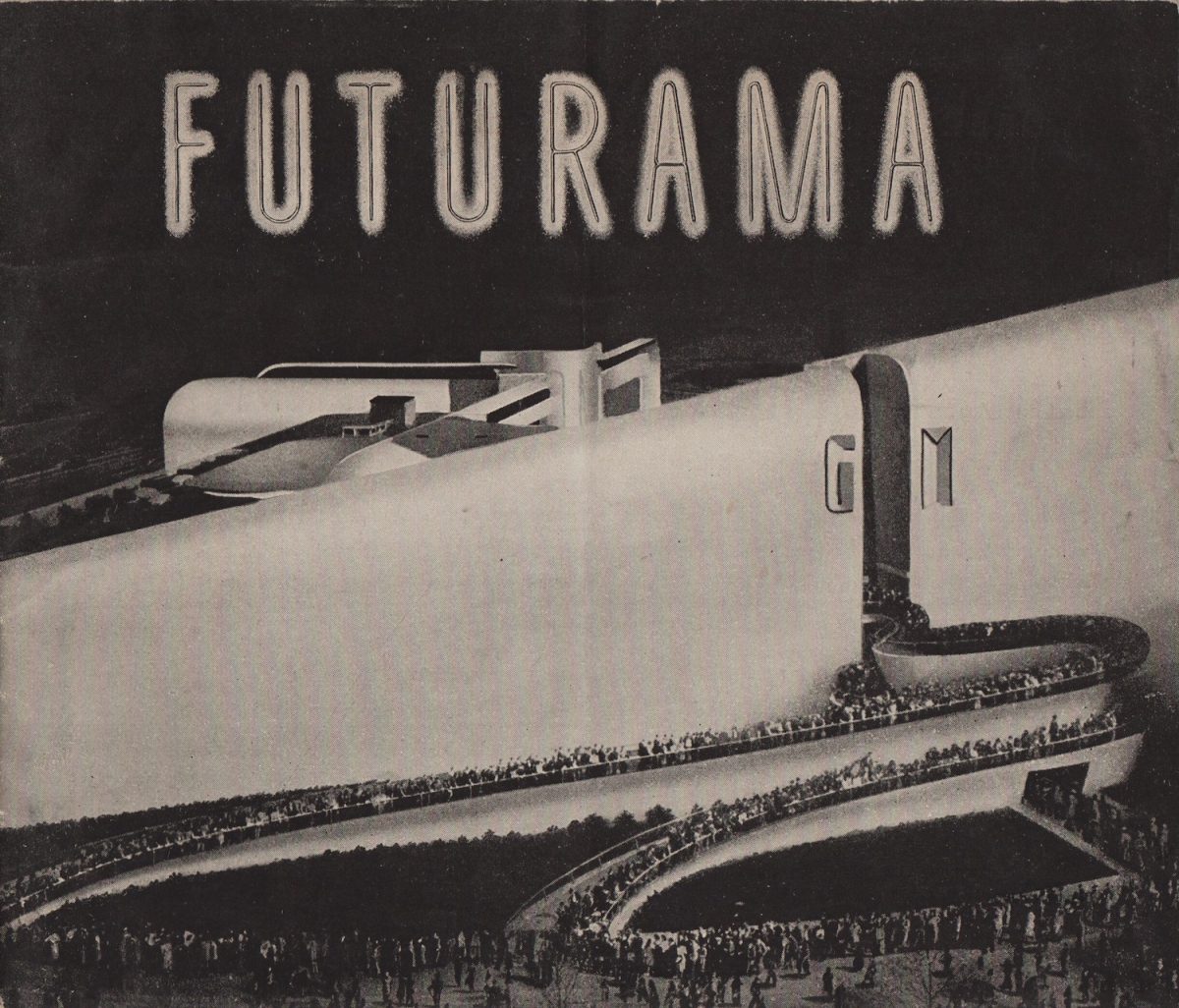

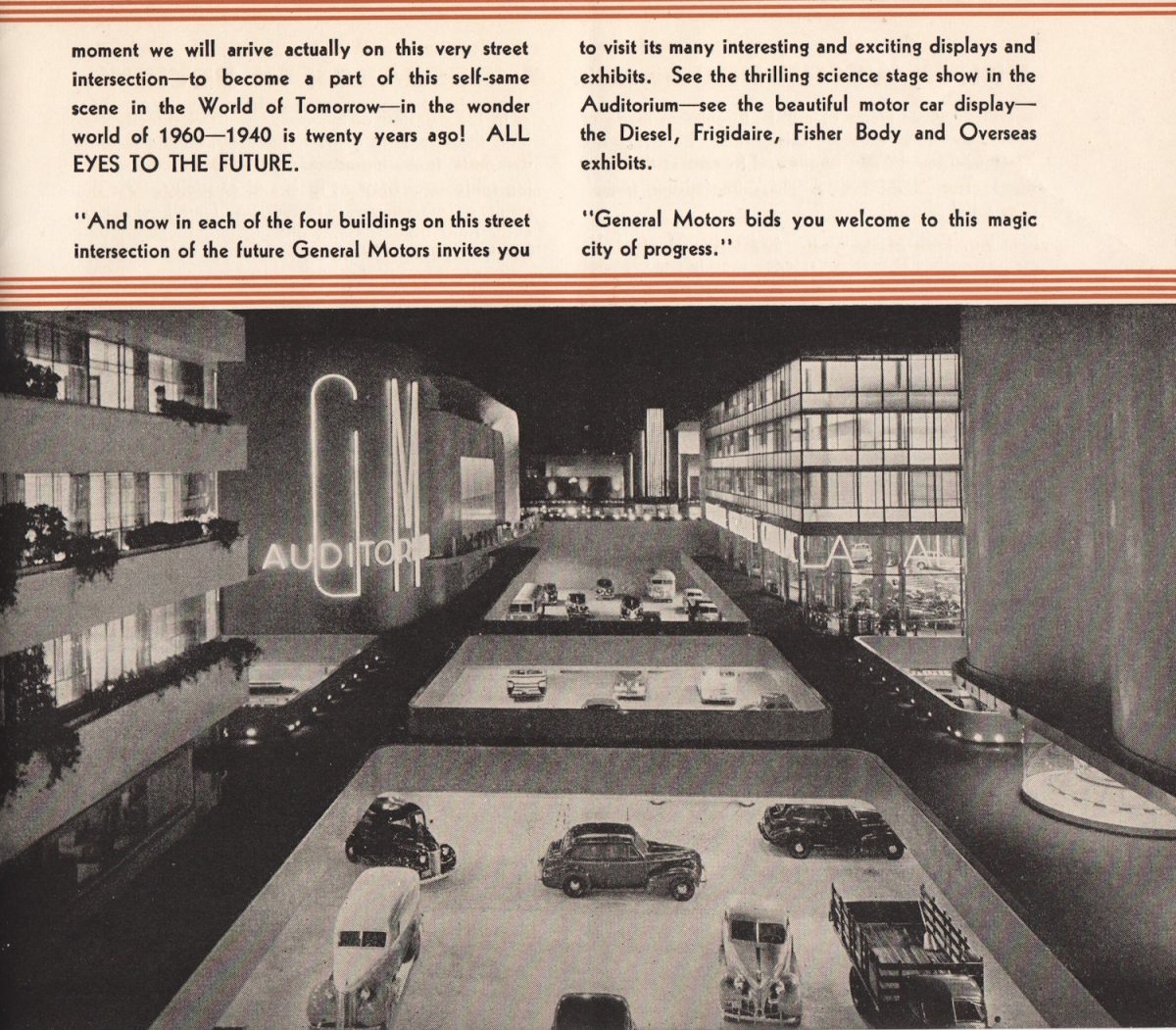

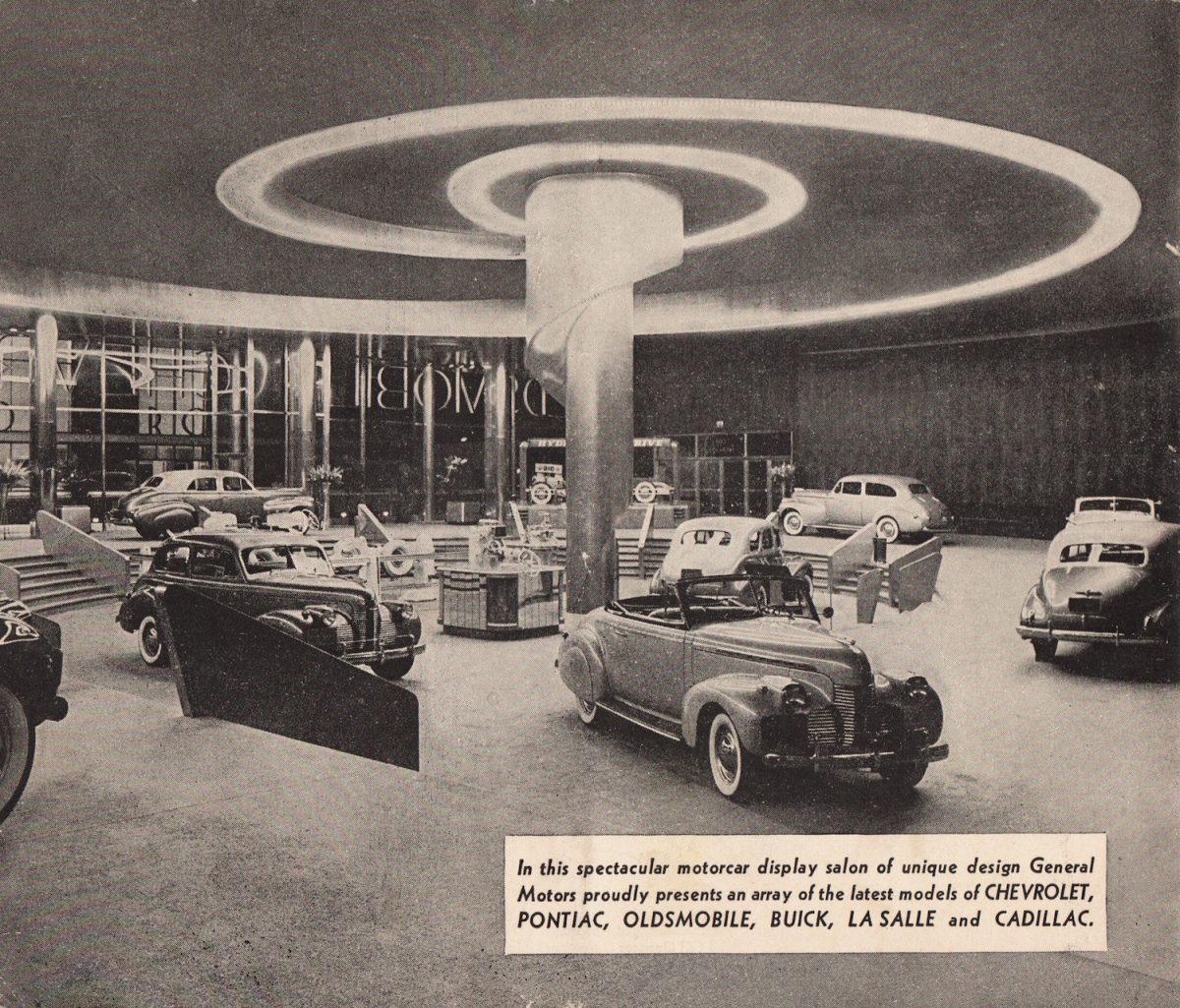

There seemed reason enough for hope that world governments, corporations, civic groups, and other organizations flocked to the 1,200-acre site in Queens, a former ash dump, to set up exhibitions and pavilions, including model cities like General Motors’ Norman Bel Geddes-designed “Futurama” and a utopian diorama called “Democracity.” Alongside these sci-fi spectacles sat monuments to commerce like the National Cash Register building—in the shape of a giant cash register, naturally—and the Carrier Air Conditioning building, an igloo.

Next to these celebrations of capitalism was the “Government Zone,” pavilions from 60 countries including Britain, Greece, Japan, Poland, Italy, the USSR, and a Jewish Palestine pavilion, which introduced plans for an independent Jewish state to fairgoers. Poland shrouded its display in black after the Nazis invaded in September.

Germany did not participate, having first committed, then withdrawn from the fair under a great deal of controversy and protest. “How does a dictator start on his way?” asked Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia during the July 4th ceremonies in the Court of Peace. “By first picking the weakest minority, abusing and oppressing it; then moving on to another.”

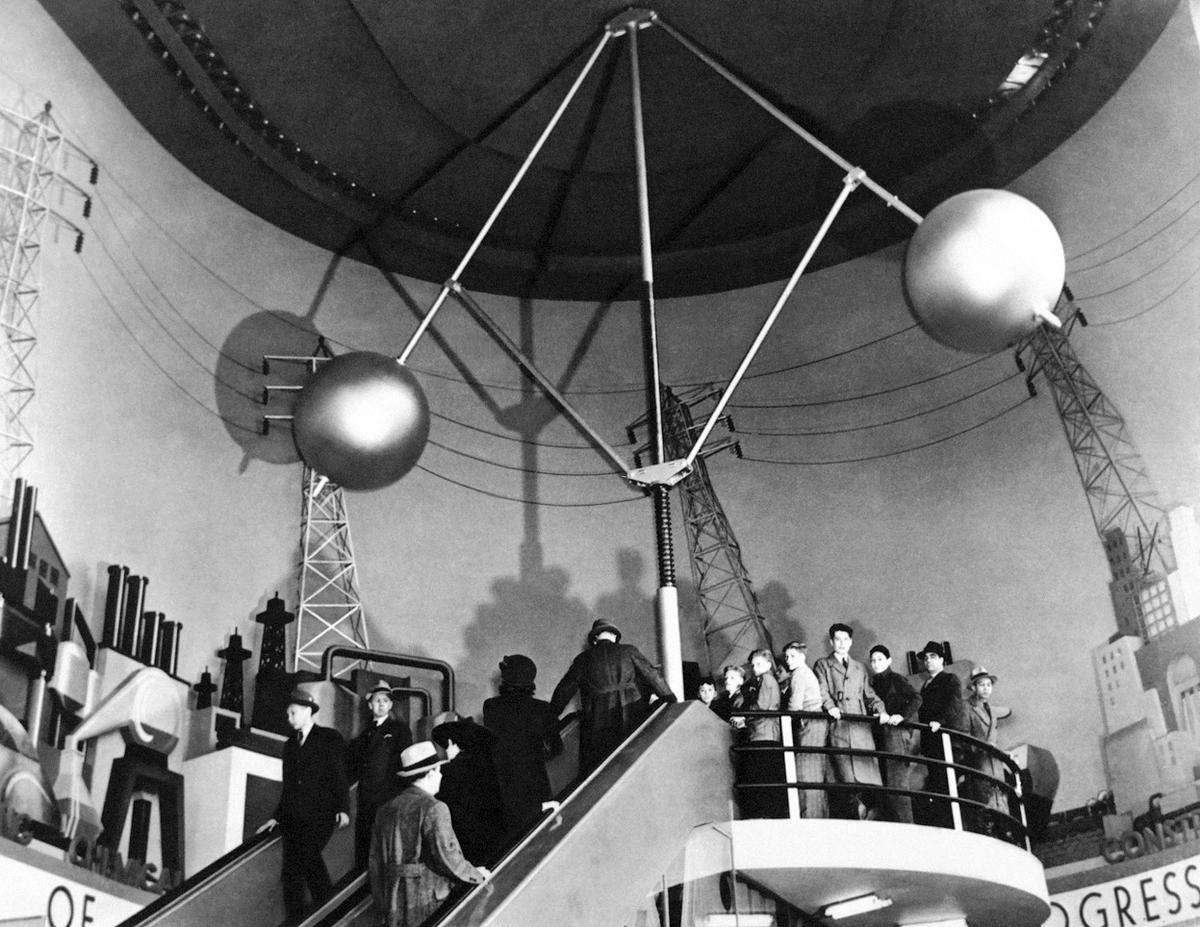

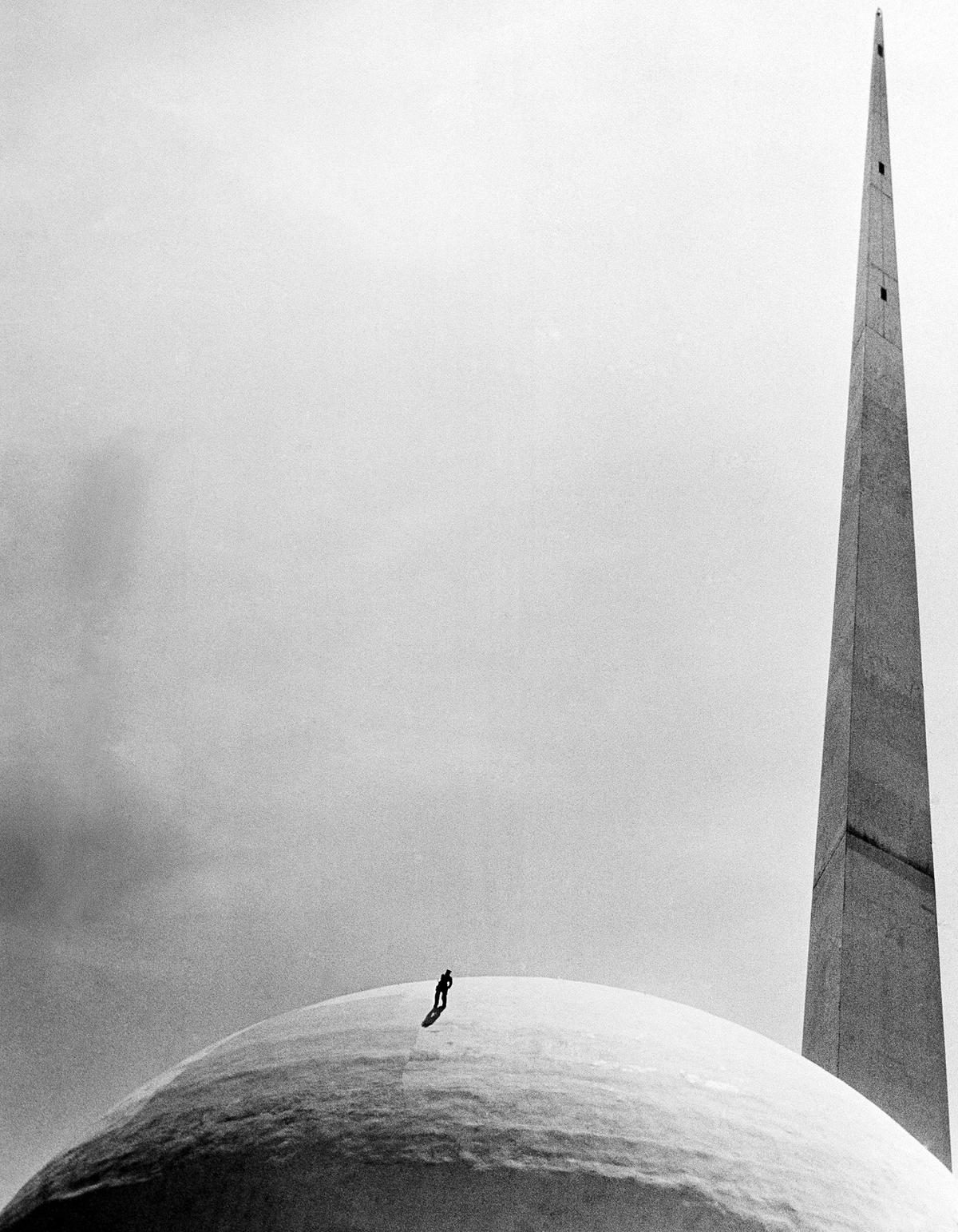

At the center of the huge event were the piercing, elongated Trylon, 700 feet high, and the giant, 200-foot Perisphere—or the “spike and ball”—which could both be seen from certain vantages in midtown Manhattan several miles away. “Inside the 18-story Perisphere,” wrote the Daily News at the time, “in an auditorium the size of Radio City Music Hall, thousands rode on two moving balconies and looked down on Democracity, a mammoth model of the city of tomorrow—a city of broad streets, many parks, and large buildings.”

A few other notable attractions at the Nw York World’s Fair included the first “time capsule”—or the first object of its kind to be given the name, anyway; Elektro, Westinghouse’s 7-foot-tall robot with a 700-word vocabulary; an “electric stairway” at the Westinghouse pavilion; previews of the coming highway system at the General Motors pavilion; and a “Miss Nude of 1939” contest at the Cuban Village.

The Fair promised and truly delivered “The World of Tomorrow,” which the News wrote of as “that gleamingly marvelous place where every home had an electric waffle iron and an automatic washing machine and were robot cars sped efficiently along the super-expressways that linked great domed cities.”

These predictions, tongue-in-cheek though they may be, proved prescient. Or at least the exhibitions created burning desires for modern conveniences people had never known they needed. As Wired describes it, “What people saw at the fair, they wanted for themselves. And when World War II ended, the American consumer machine began giving them what they wanted, or at least what they thought they wanted, or maybe even what the marketers thought the public thought they wanted.”

The Fair’s influence on science fiction (and sci-fi parody), industrial, commercial, and urban design, and marketing resonates into the present. After its first year, however, the shiny optimism seemed a bit too much even for the organizers, who officially gave it a new theme in 1940: “For Peace and Freedom.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.