“It isn’t so much what’s on the table that matters, as what’s on the chairs” – Jonathan Swift from letter to Stella (1711)

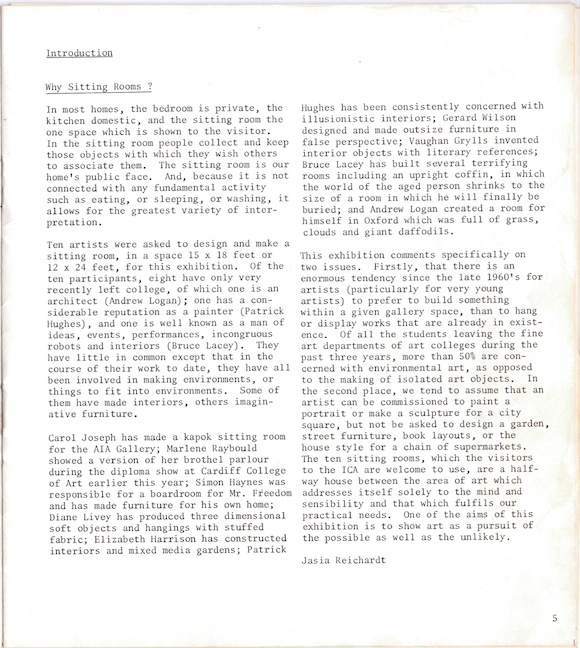

Ten Sitting Rooms was the title of a group exhibition curated by Jasia Reichardt at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1970. She organised a budget of £100 for each artist and gave them the brief of making a sitting room in spaces of either 15 x 18 feet or 12 x 24 feet.

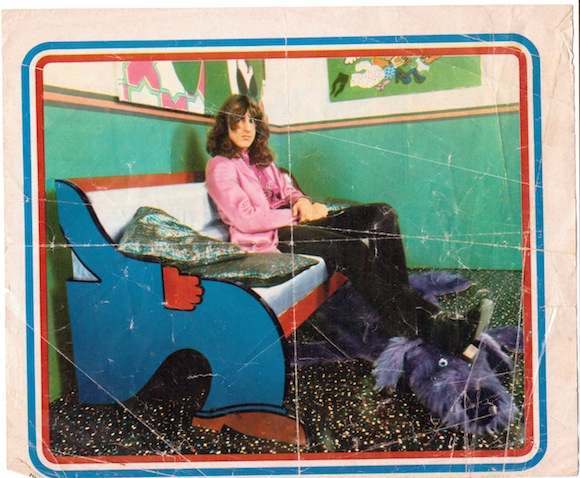

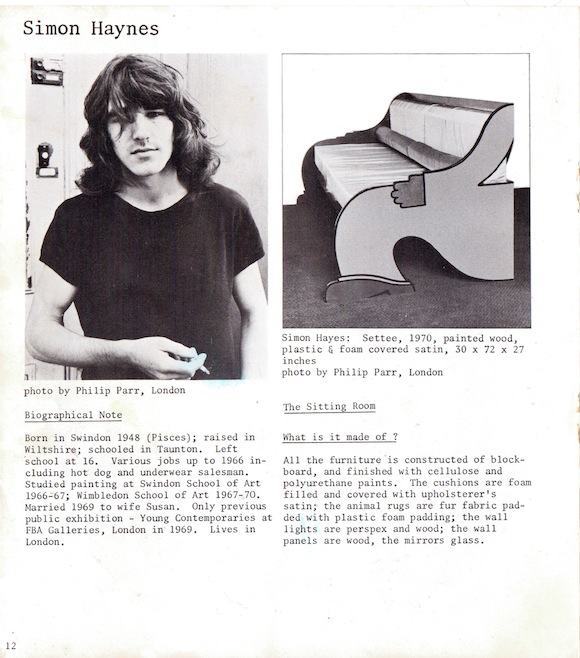

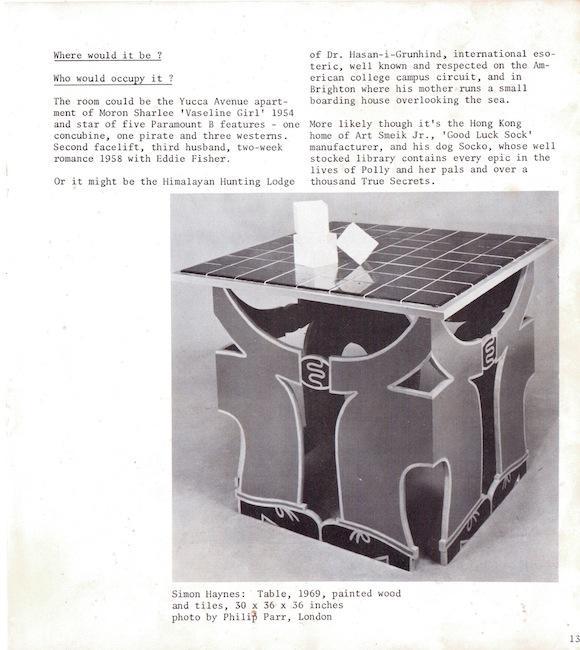

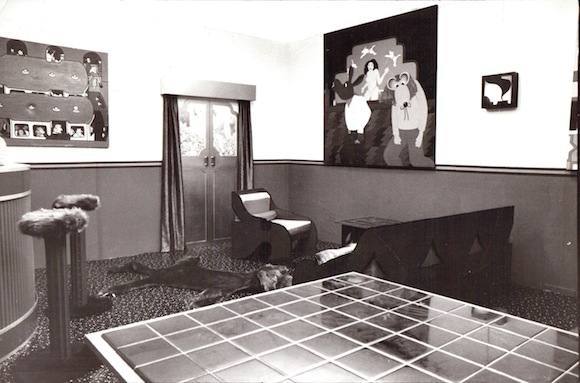

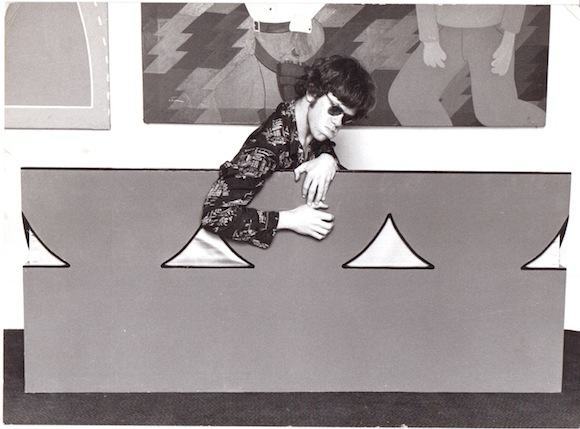

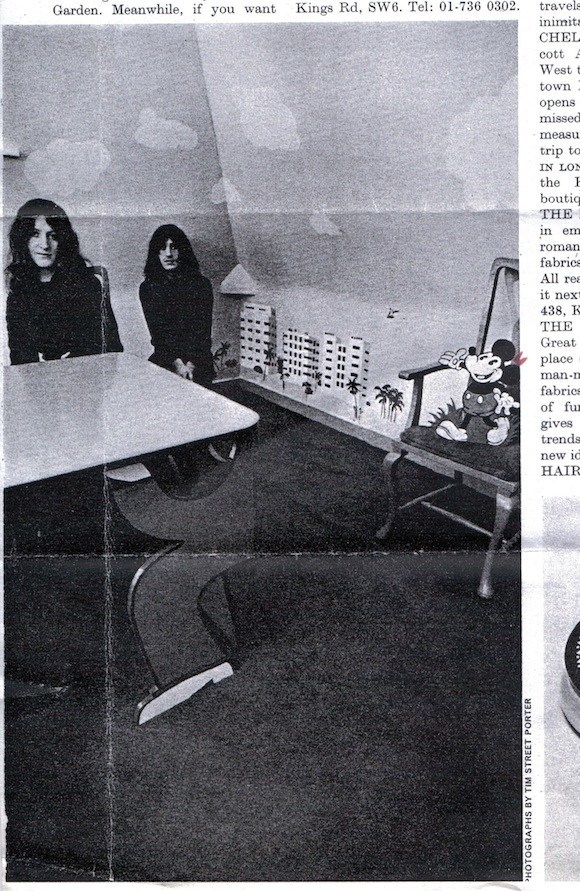

I was alerted to the show’s existence by participant Simon Haynes, whose work I have been featuring here. Haynes’ Pop environment, which was produced in collaboration with his wife Sue, developed the themes and materials they used in the boardroom interior and furniture created earlier that year for Trevor Myles’ and Tommy Roberts’ boutique Mr Freedom at 430 King’s Road.

In the show catalogue Jasia Reichardt explained that the sitting room was chosen because it “allows for the greatest variety of interpretation”. Visitors to the show were invited to use the spaces since the 10 created by the artists represented “a halfway house between the area of art which addresses itself solely to the mind and that which fulfils our practical needs”.

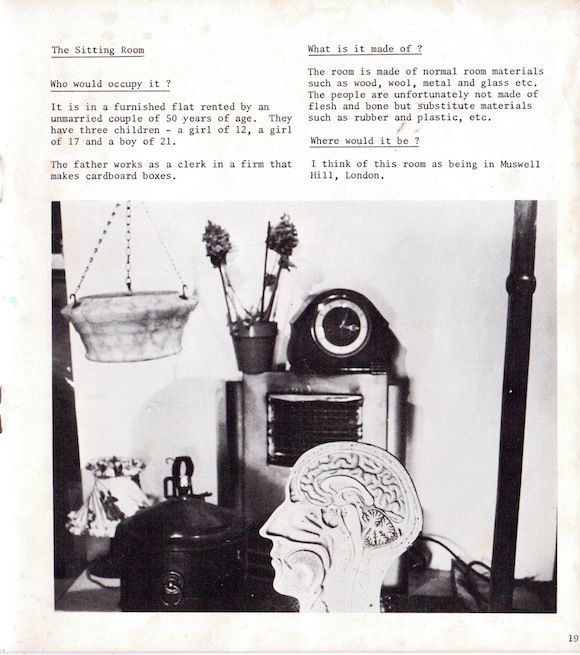

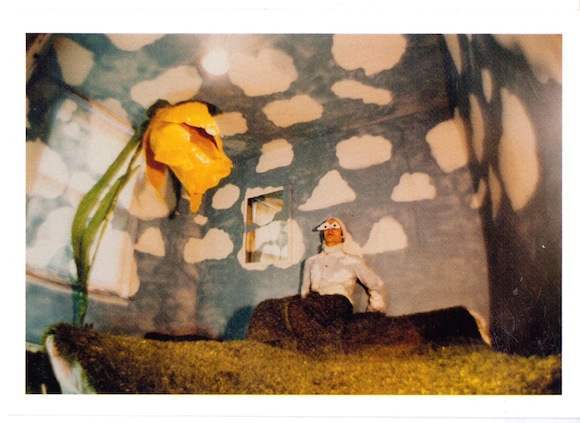

The exhibition presented work by such notables as Bruce Lacey (subject of Nick Abrahams’ and Jeremy Deller’s terrific 2012 documentary) and Patrick Hughes. There were several recent art school graduates aside from Haynes, including Andrew Logan, who had just emerged from Oxford School of Architecture and presented an environment similar to his student lodgings at 10 Denmark Street, Oxford. In his biographical note, Logan revealed he was working on the decor of the milliner’s shop run by his sister Diane in London’s Chiltern Street.

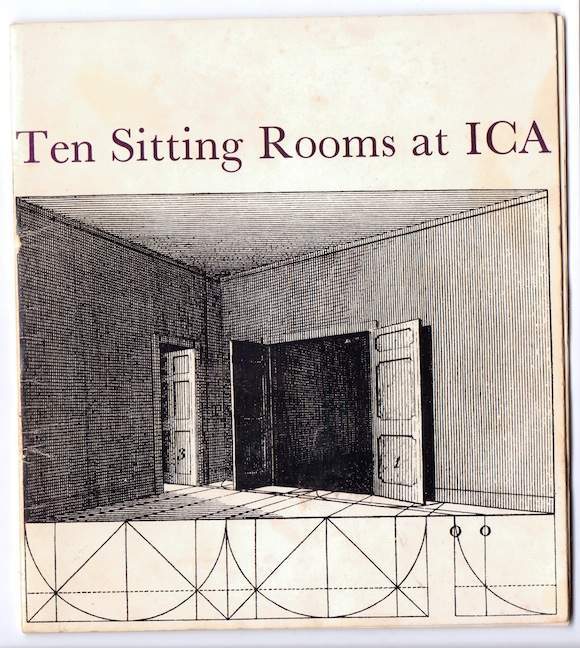

The catalogue is a handsome document. Designed by John Furnival, the artist bios and details of their artworks are supplemented by a short story by Ivor Cutler, a cartoon by Norman Toynton and photographs of sculptures by Penny White and Roger Kent.

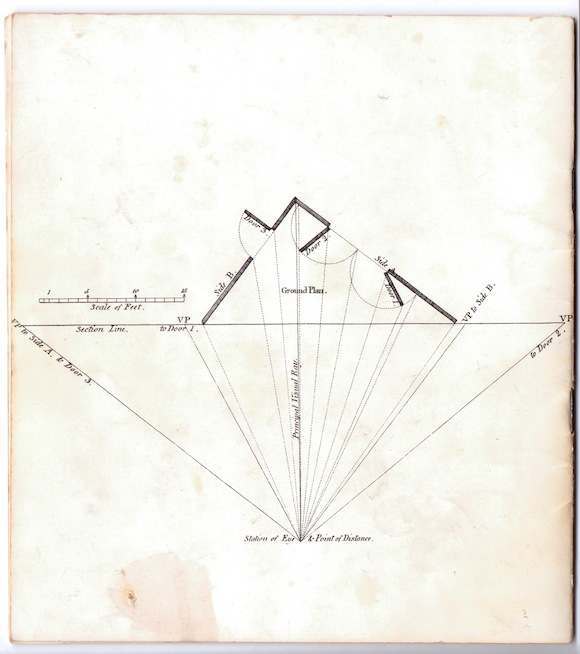

The cover reproduces The Converging Of Various Planes, a work by Charles Hayter, the 19th century miniatures painter and Professor of Perspective to her Late Royal Highness The Princess Charlotte of Saxe Cobourg.

This was taken from Hayter’s 1820 book (deep breath) An Introduction to Perspective, Drawing and Painting, in a Series of Pleasing and Familiar Dialogues between the Author’s Children; illustrated by appropriate Plates and Diagrams and a Sufficiency of Practical Geometry; and a Compendium of Genuine Instruction, comprising a Progressive and Complete Body of Information, carefully adapted for the Instruction of Females, and suited equally to the Simplicity of Youth and to Mental Maturity.

Visit Jasia Reichardt’s archive of concrete and sound poetry here.

Find out more about The Bruce Lacey Experience here.

John Furnival’s work has included founding the Openings Press and performances with the concrete poet Dom Sylvester Houédard. Read more about him here.

A selection of the other participants:

This was to be my first London show as a working artist. I collected some of my pun-sculptures, covered the walls, ceiling and floor of my room at the ICA with black fur fabric and placed my sculptures in it. My room looked good with the black and white objects, giving the appearance of furniture in a three-dimensional monochrome photograph. To emphasize this further, I had each pun-sculpture photographed, and the large black-and-white prints displayed at strategic points on the walls. I ensured that the surface quality of the prints and the black and white tones within them replicated exactly the look and feel of the sculptures. The result was so satisfying that from this point on, photography became an integral part of my work.

I then wrote the following and displayed it in the room:

Professor Vaughan Grylls holds the Chair of Philosophy at the Episcopalian University of Soaring Spires, Idaho. He achieved eminence early in his career with his notorious dissertation ‘Why Words’, which he first read as a paper before the Society for the Analysis of Arcane Language shortly after graduation. In this paper he demonstrated that conventional, indeed scholarly, language structures could be accompanied by a total absence of meaning. Professors were puzzled and logicians angry. But more was to come, a complete breakthrough in the history of semantics. Grylls rejected language as a viable medium. Claiming that all language re-structures and thereby distorts thought, he delivered a series of quietly brilliant lectures on ‘the silence of communication’. At first students were nonplussed. Later they appreciated his taciturnity. Things now began to move fast. Grylls was appointed to the coveted position of Drone’s Professor of Comparative Languages. Sacked from this post the following year, he published the theory that had led to his dismissal. This was the famous ‘Alice paradox’. Grylls was grappling with the gap between intention and expression: as Alice was instructed, a person can mean what he says without saying what he means. ‘We have to find the way to say what we mean; if we mean what we say, we must weigh what we mean’. Colleagues were scornful. But in an article entitled ‘On, Means and Says’, published a month later, Grylls affirmed that he meant what he said. His genius was coming to be recognized.

Satisfied that language was moribund, Grylls became interested in the possibility of thought without words. He wanted to give an account of that moment in which a concept is formed but has not yet been articulated in words, the pre-verbal implosion, as he called it. In pursuit of this aim he photographed himself in various postures of tortured cogitation. These photographs he sent to the Journal of Behavioural Psychology. They were politely returned and now hang on his walls. But he continued to startle the academic world, this time with his extreme liberalism. Students not yet attuned to the silence of his lectures were permitted to make free with his wife. She gave birth to several children while he was working on a new book. In this he drew an analogy between sexual ethics and outmoded language structures. It was called ‘Pre-verbal Implosions and my Wife’. ‘Cretinous’, pronounced a Harvard professor when it was published. Meanwhile, more children were born.

After the death of his wife, Grylls embarked on his most famous scheme: solid language. His radiogram and lectern exam paper, constructed on his return from London, England in 1969, consummated his career.

Grylls is a man of principle. He has exposed the inadequacy of language in a hundred books. Bereft of students, surrounded by bastards, he sits in triumph among the ruins of his liberalism and learning. No words can describe him.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.