As the U.S. lurches through the pandemic and stumbles toward another depression, some places in the country already look like the Hoovervilles of the 1930s. The eviction crisis will swell the ranks of the homeless even more. These events seem almost invisible now, and there may not be much visual record of them for posterity it sometimes seems, given the collapse of local journalism and most government programs.

During the time of the Great Depression, however, the U.S. government coordinated a response to document New Deal programs like the Farm Security Administration. Photographers canvassed the country, and their efforts produced some of the most iconic images in its history. We know the famous names: Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Gordon Parks. We should also know John Vachon, who began his career as a photographer for the FSA before going on to take photographs for Standard Oil, Life, and Look.

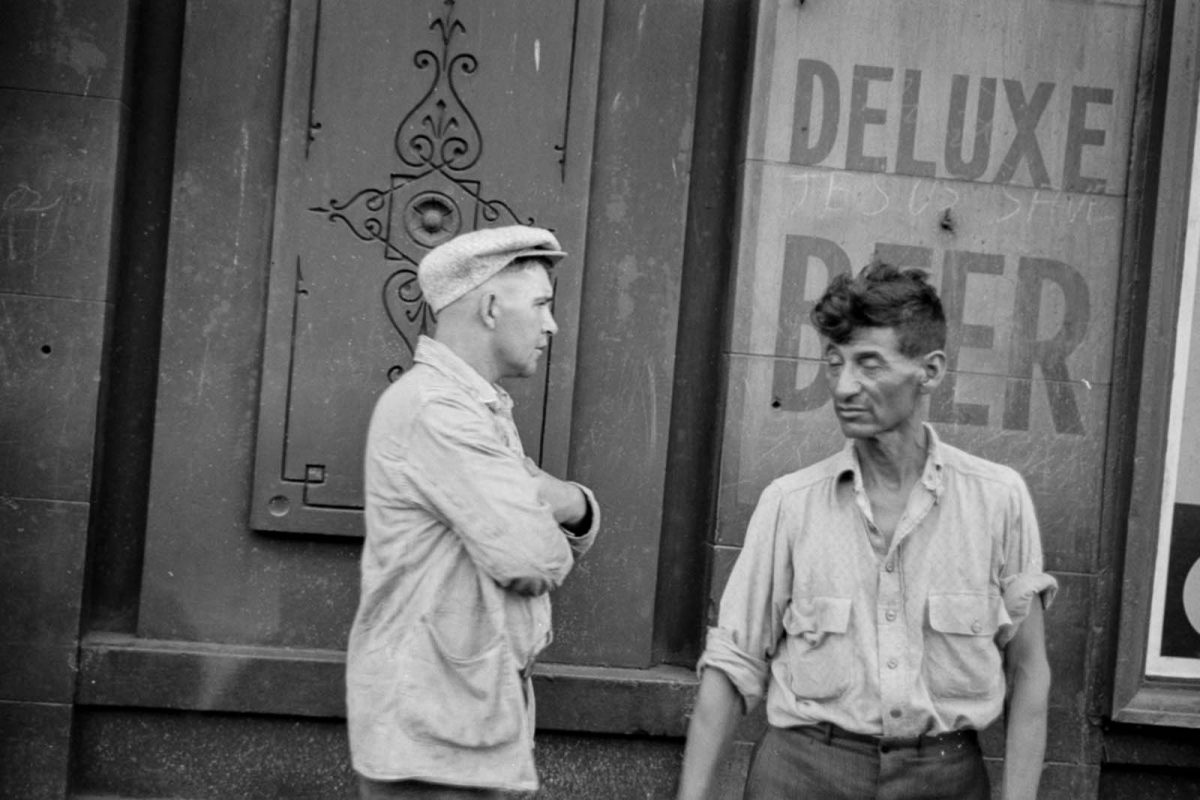

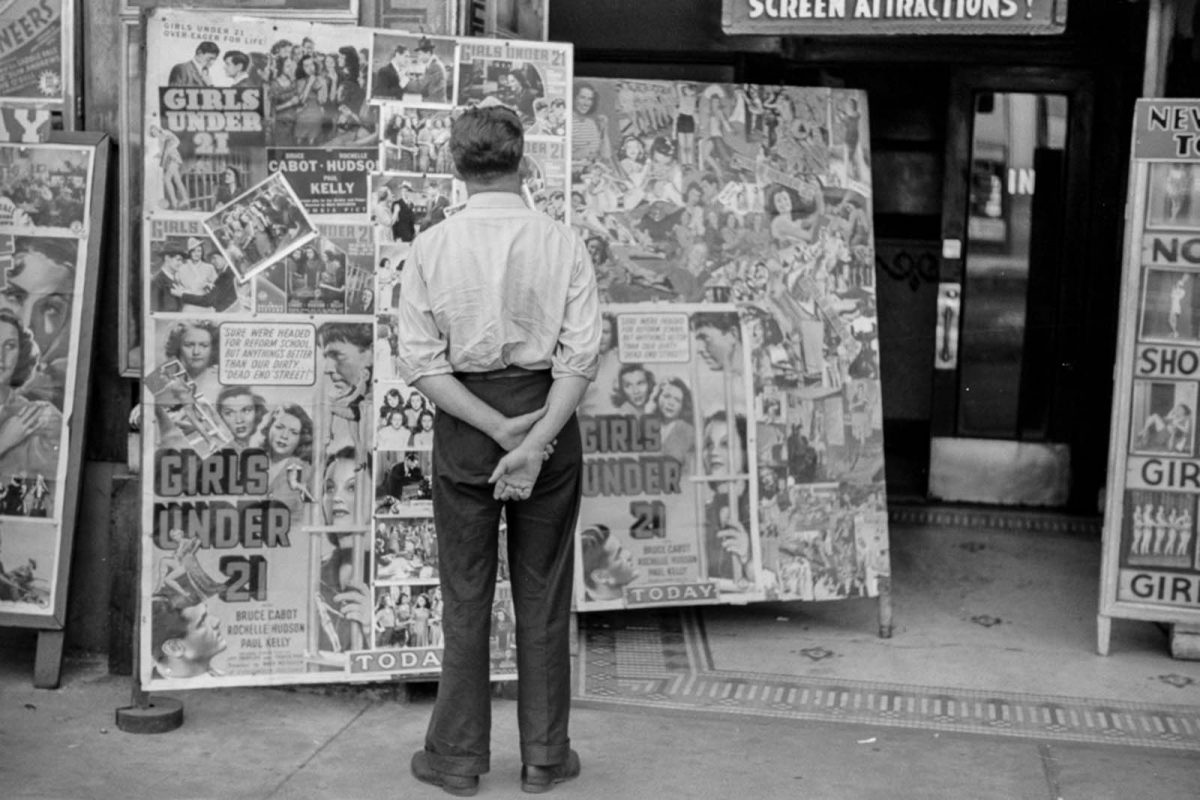

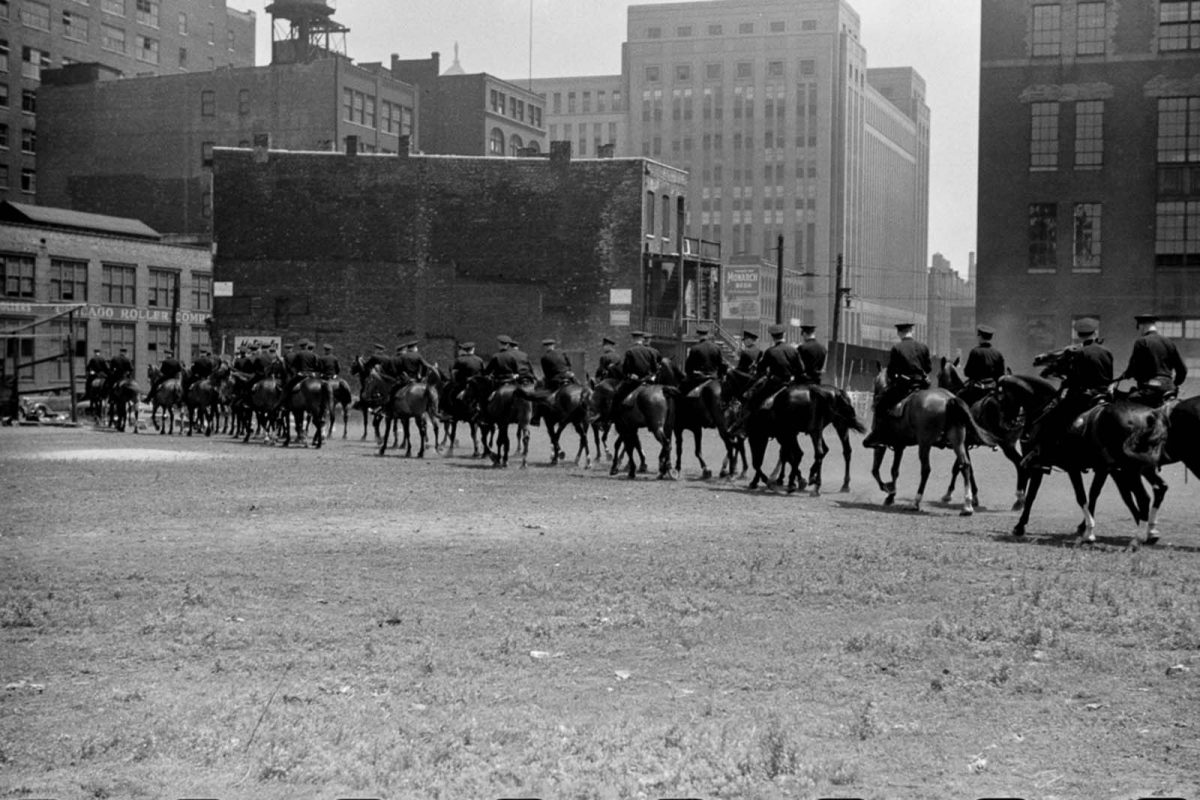

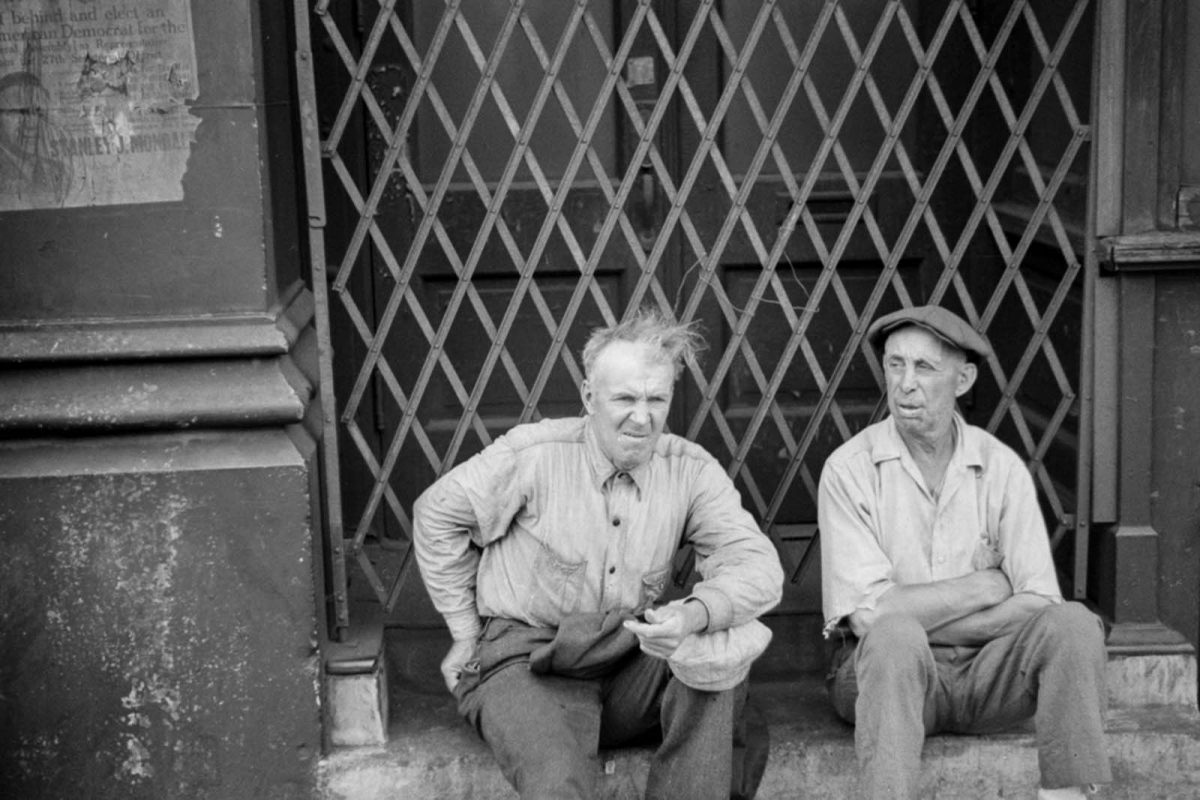

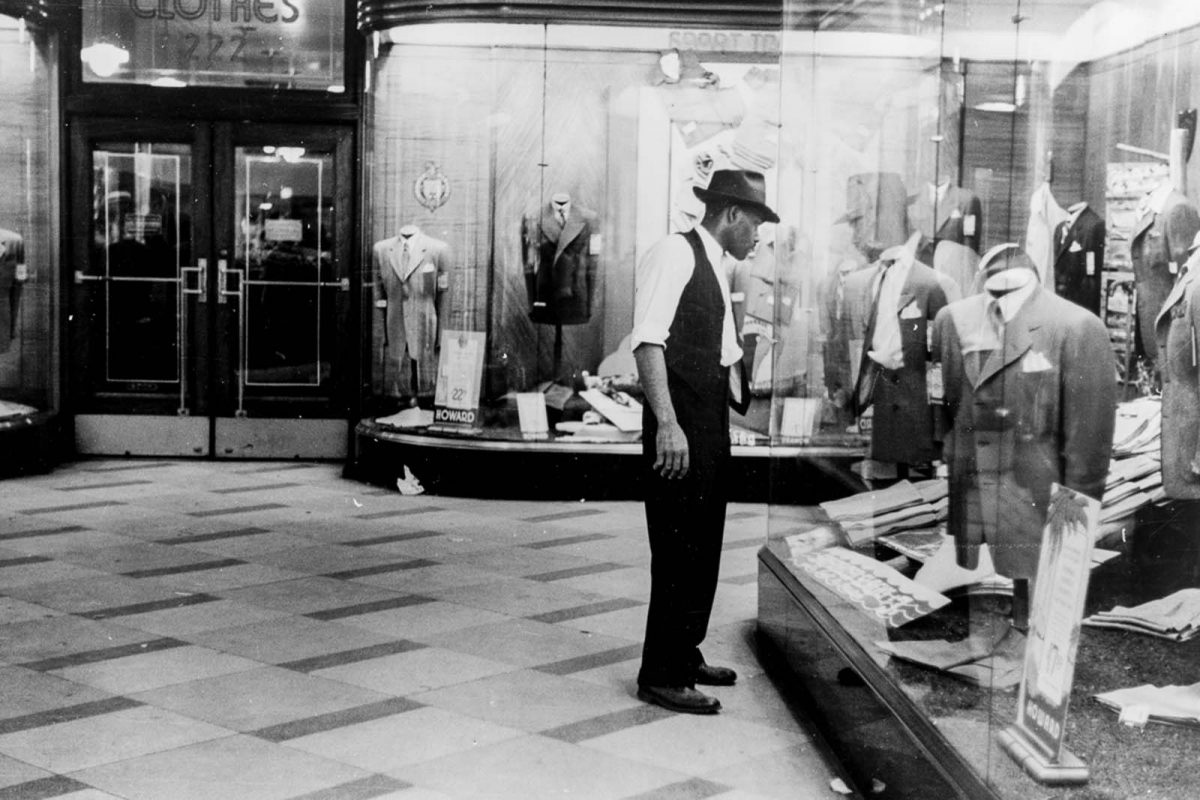

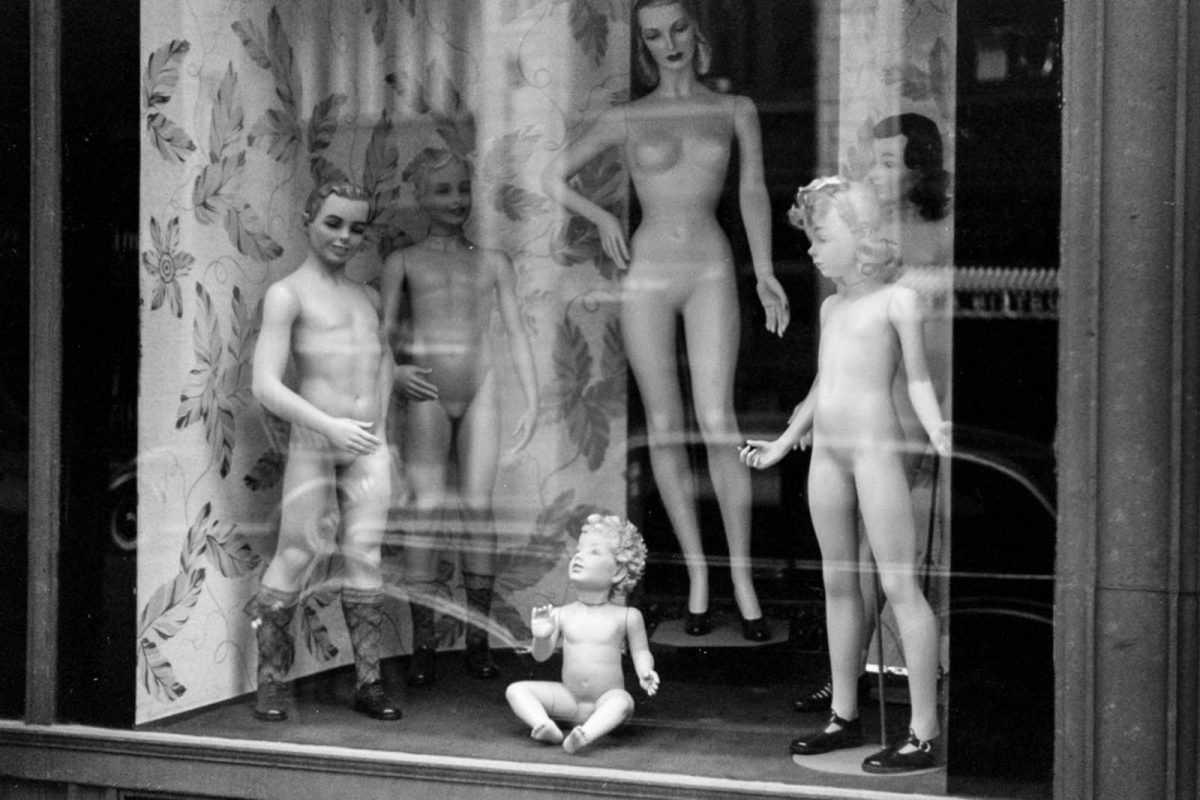

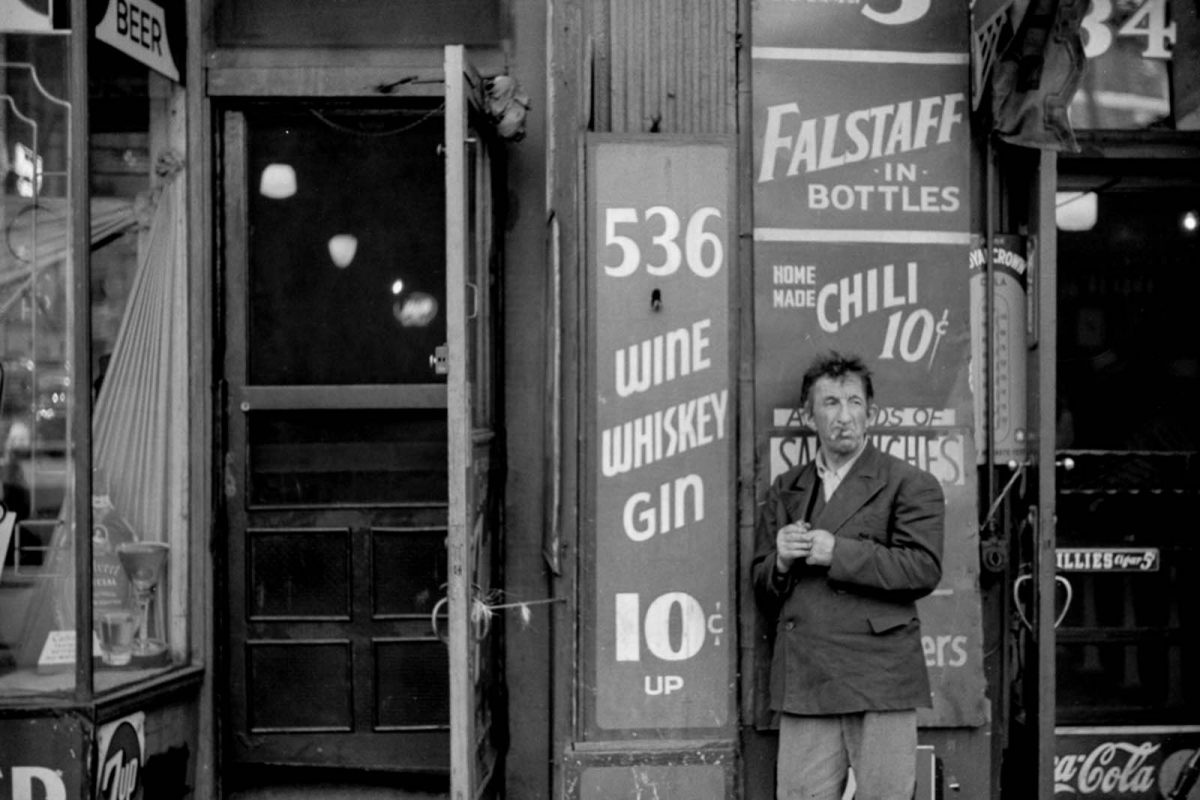

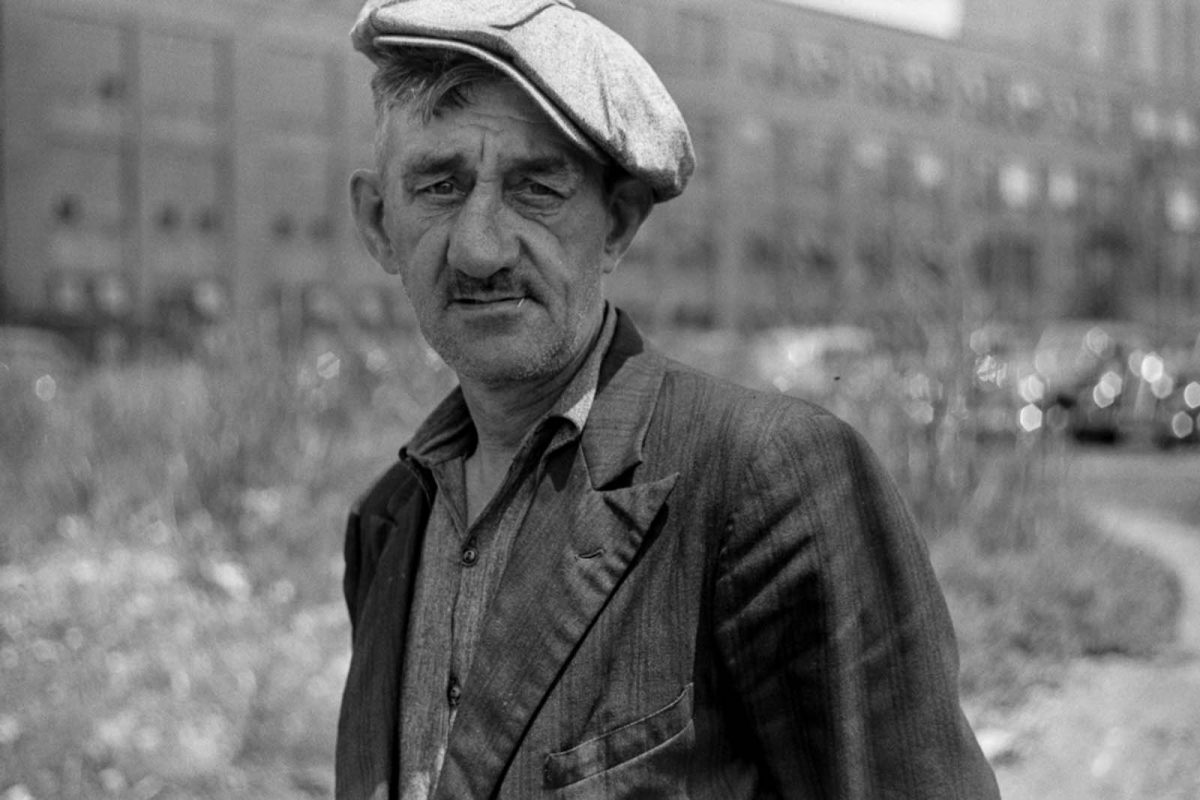

Vachon didn’t produce one singular, iconic cover image like Lange’s Migrant Mother or Parks’ Washington D.C. Government Charwoman. But many of his photographs could have drawn such focus. Only he had a particular style all his own. Vachon photographed what others might consider irrelevant or mundane, in such a way as to give odd details a numinous significance too ambiguous to serve the purposes of bare documentary or polemic.

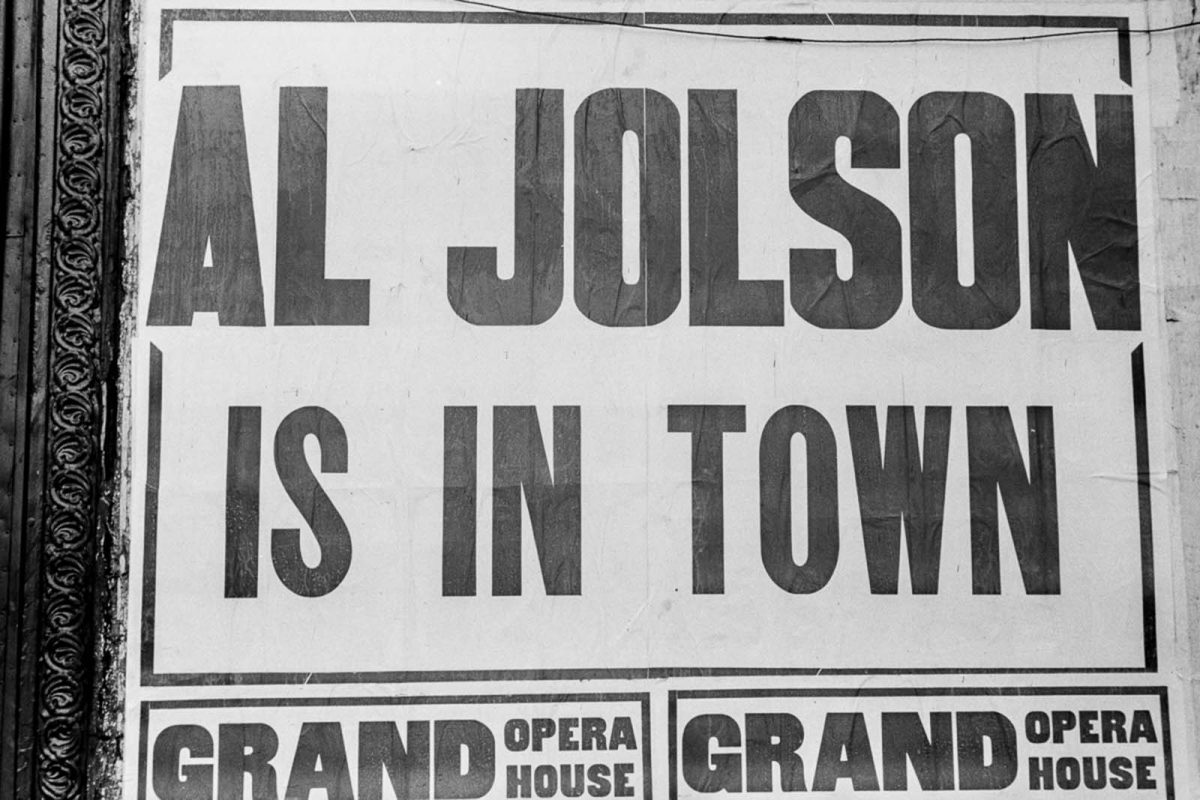

Sent to Omaha, Nebraska on his first assignment in 1938 by director of the FSA’s Historical Section, Roy Stryker, Vachon was supposed to illustrate the power struggles between rich and poor detailed in a book by journalist George Leighton. Only five of his photographs were used. “The Omaha in Vachon’s photographs is more varied and complex than the one in Leighton’s text,” notes the Library of Congress.” Vachon’s “curiosity about how things look outstripped his intellectual involvement in history and sociology.”

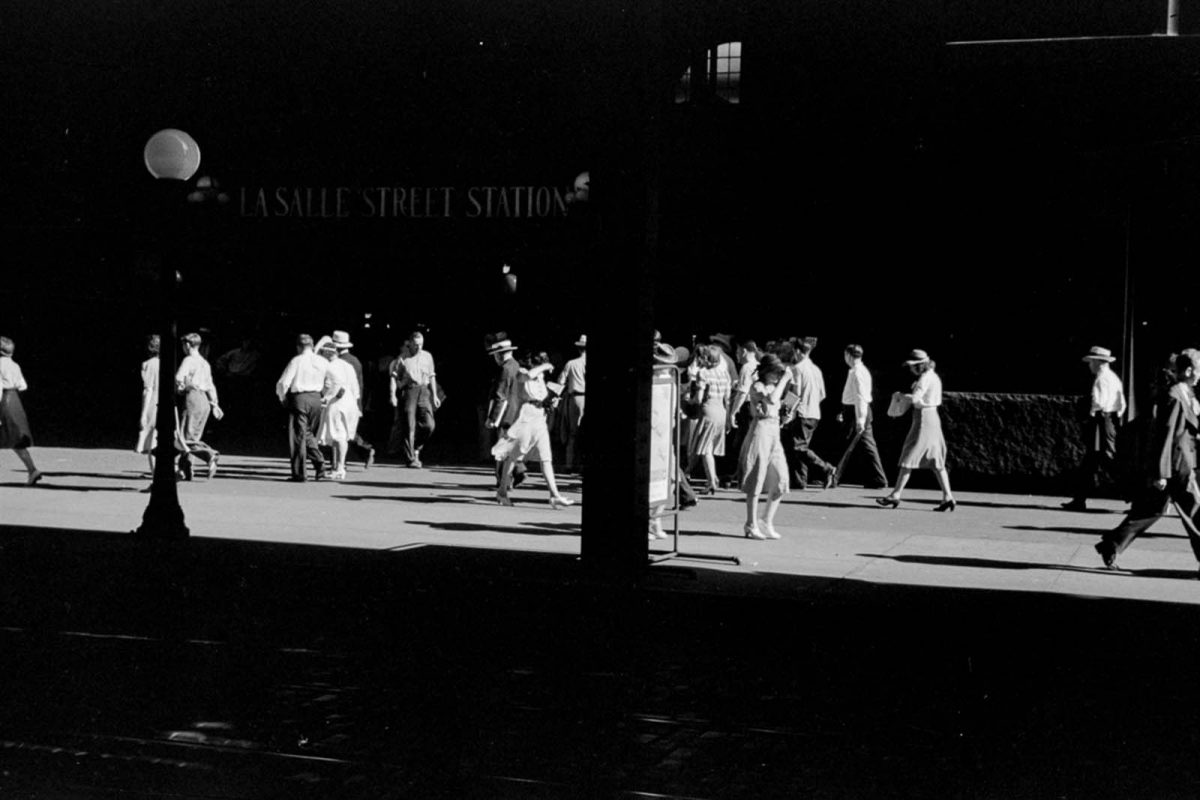

In his work we can locate later street photography’s obsessive focus on seemingly extraneous detail to the exclusion of the obvious. Subtleties lost in promotional or tourist photography turn out to be extraordinarily illuminating to the right viewer. It was in Omaha that Vachon found his eye. “One morning I photographed a grain elevator,” he remembered in a 1973 interview, “pure sun-brushed silo columns of cement rising from behind CB&Q freight car. The genius of Walker Evans and Charles Sheeler welded into one supreme photographic statement, I told myself.”

Then it occurred to me that it was I who was looking at the grain elevator. For the past year I had been sedulously aping the masters. And in Omaha I realized that I had developed my own style with the camera. I knew that I would photograph only what pleased me or astonished my eye, and only in the way I saw it

The photographer took this epiphany with him to Chicago in 1941, along with all he had learned from “the masters.” Evans had “insisted that he master the view camera,” the Library of Congress points out, and photographer Arthur Rothstein first “took him along on a photographic assignment to the mountains of Virginia” to learn the ropes. Vachon photographed rich, poor, and in-between, with little attempt to construct an overarching argument. His images are small, candid vignettes that gesture toward larger conflicts outside the frame.

There is a literary quality to Vachon’s work, unsurprising given his early ambition to become a writer. He started at the Farm Security Administration as a 21-year-old “assistant messenger” after being expelled from graduate school at the Catholic University for his drinking. He would continue on at the agency as one of its most original photographers into the war years, contributing to a vast visual record of the country’s economic inequality whose like may never be seen again.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.