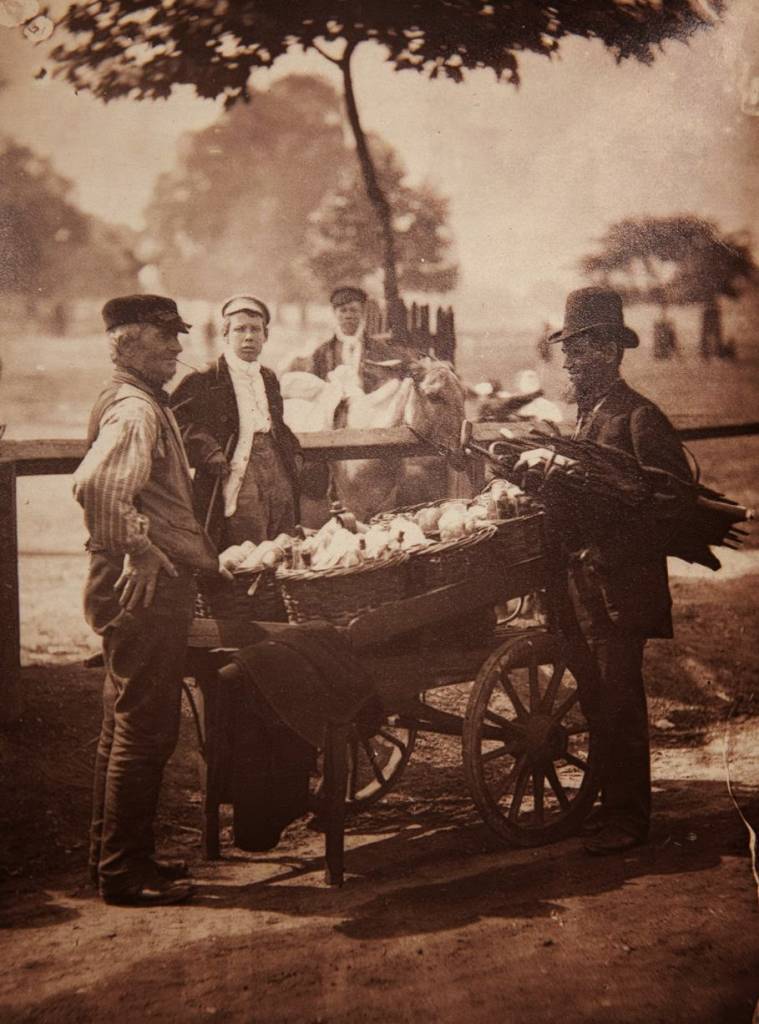

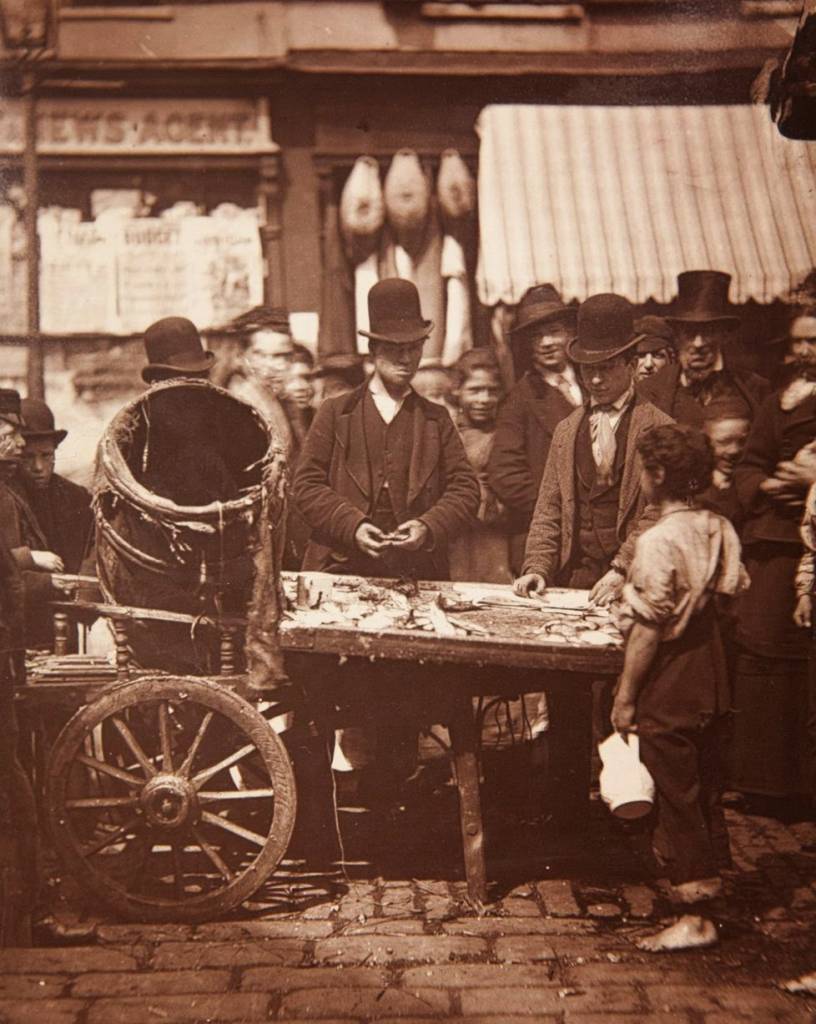

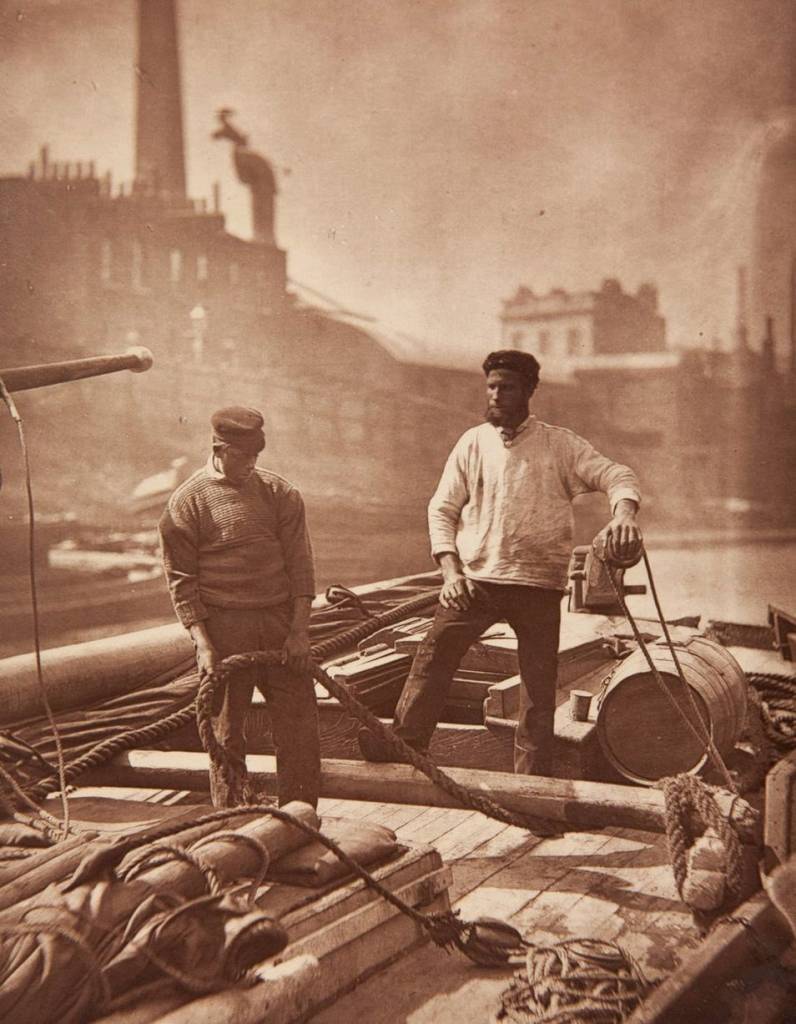

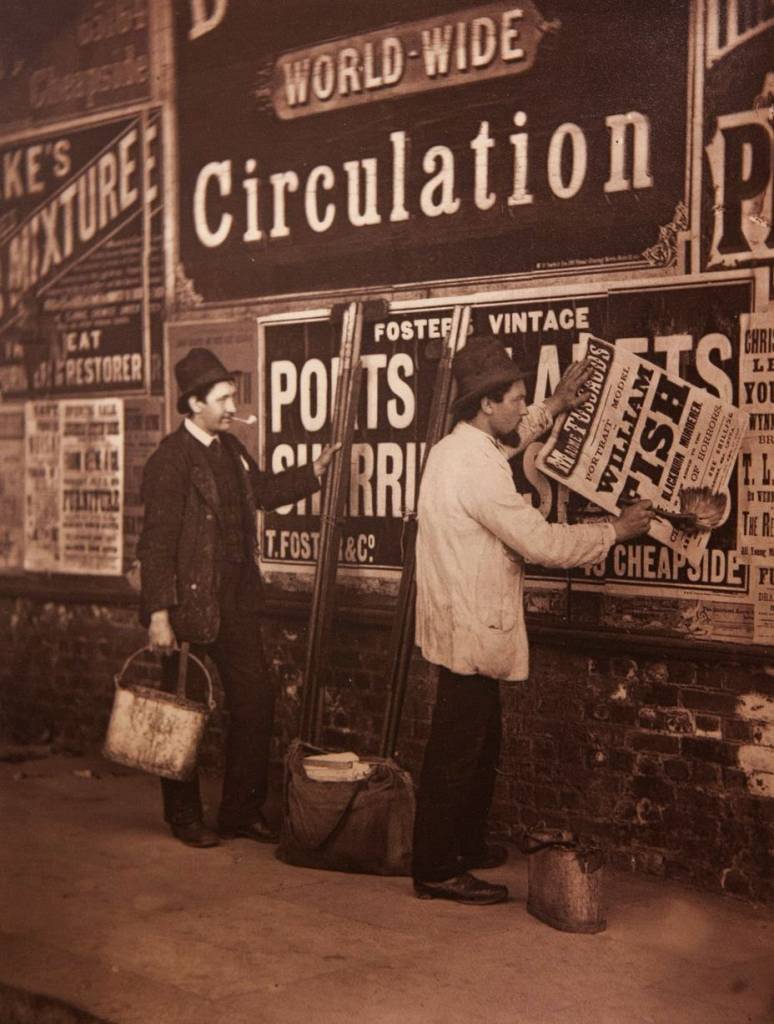

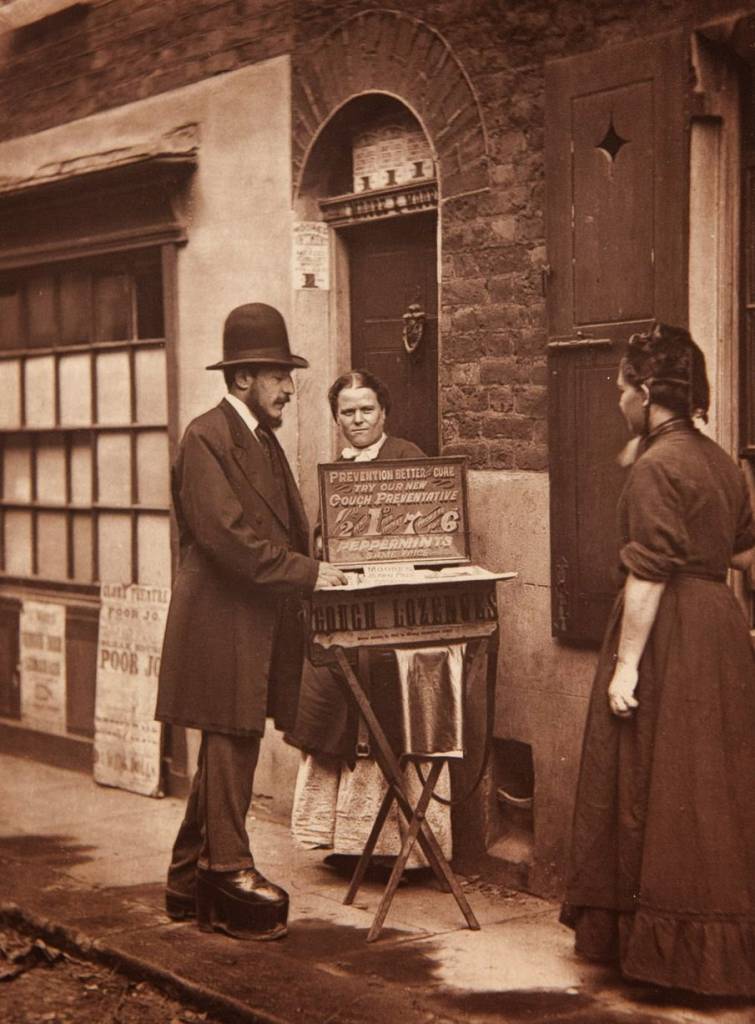

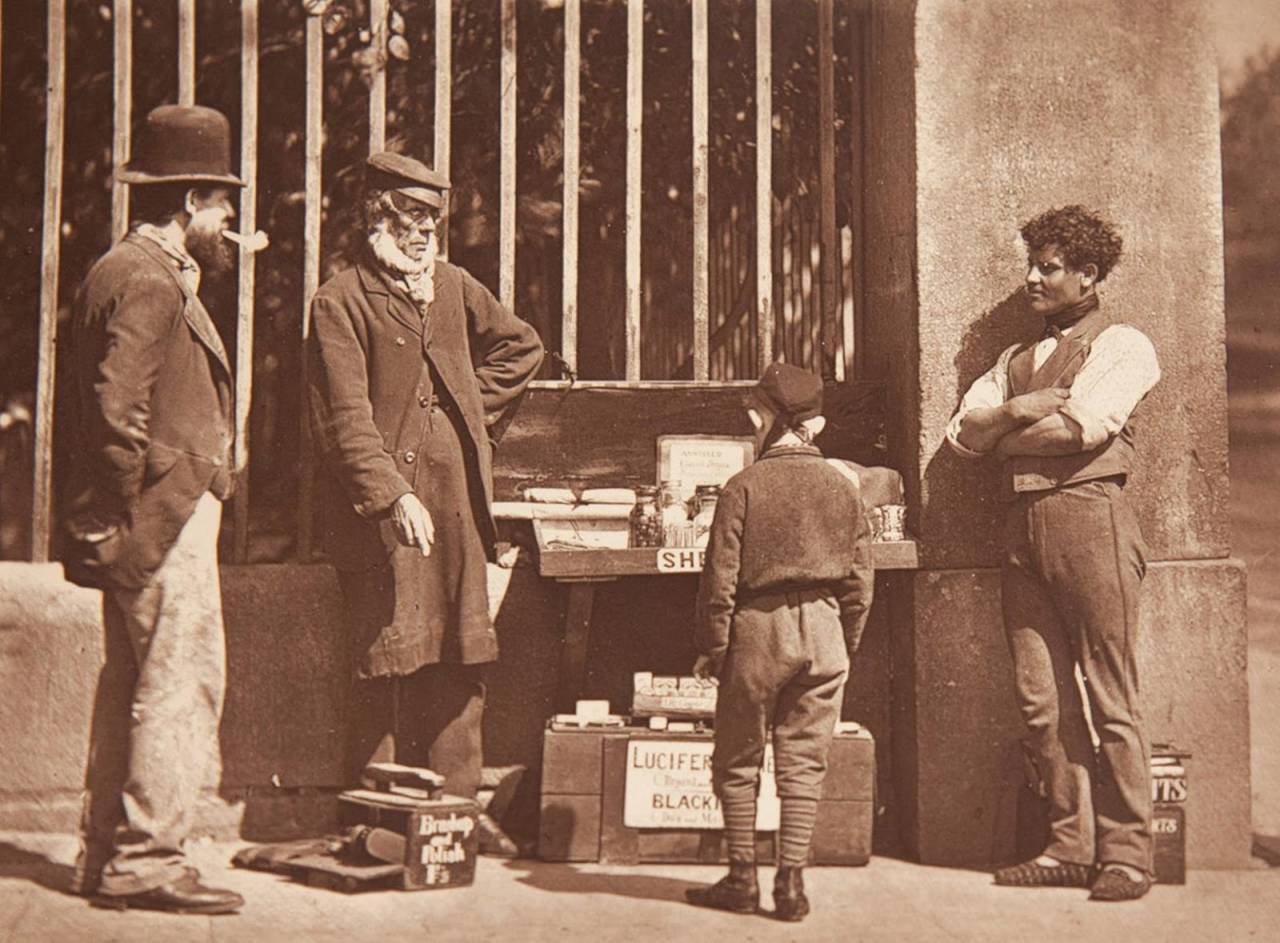

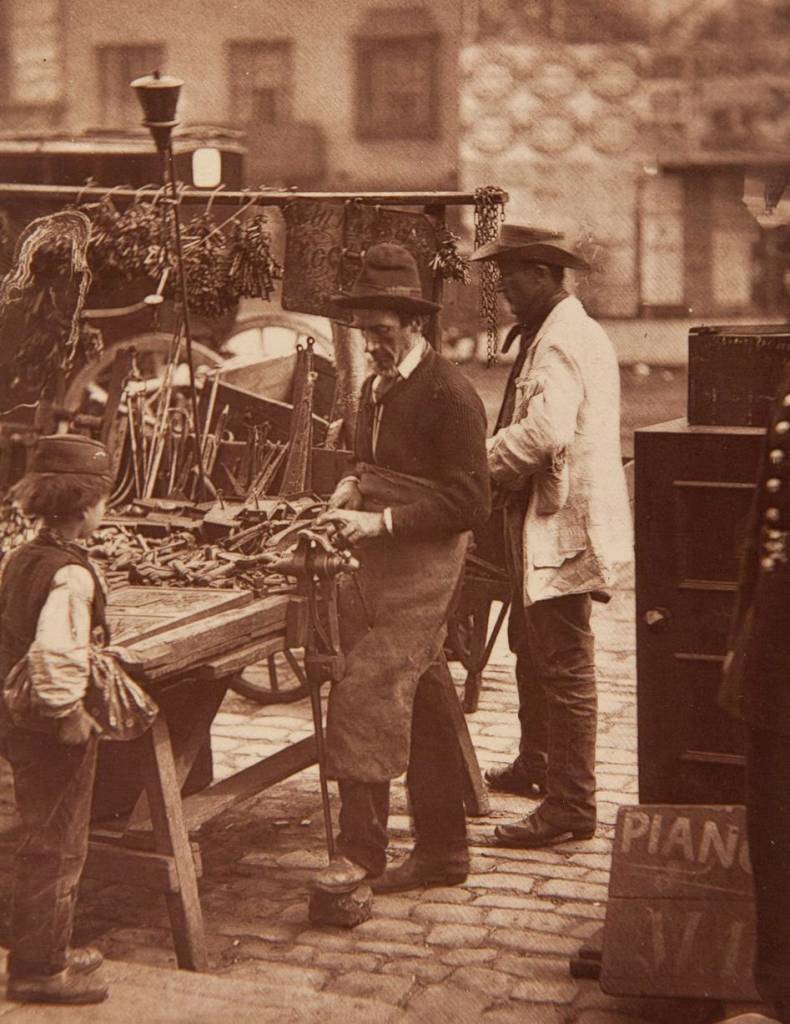

In 1877 John Thompson toured London with a camera. With journalist Adolphe Smith, Thompson would record working-class London.

PREFACE.

IN presenting to the public the result of careful observations among the poor of London, we should perhaps proffer a few words of apology for reopening a subject which has already been amply and ably treated. We are fully aware that we are not the first on the field. “London Labour and London Poor” is still remembered by all who are interested in the condition of the humbler classes; but its facts and figures are necessarily ante-dated. In later times Mr. James Greenwood has created considerable sensation by his sketches of low life, but the subject is so vast and undergoes such rapid variations that it can never be exhausted; nor, as our national wealth increases, can we be too frequently reminded of the poverty that nevertheless still exists in our midst.

And now we also have sought to portray these harder phases of life, bringing to bear the precision of photography in illustration of our subject. The unquestionable accuracy of this testimony will enable us to present true types of the London Poor and shield us from the accusation of either underrating or exaggerating individual peculiarities of appearance.

We have selected our material in the highways and the byways, deeming that the familiar aspects of street life would be as welcome as those glimpses caught here and there, at the angle of some dark alley, or in some squalid corner beyond the beat of the ordinary wayfarer. It also often happens that little is known concerning the street characters who are the most frequently seen in our crowded thoroughfares. At the same time, we have visited, armed with note-book and camera, those back streets and courts where the struggle for life is none the less bitter and intense, because less observed. Here what may be termed more original studies have presented themselves, and will help to complete what we trust will prove a vivid account of the various means by which our unfortunate fellow-creatures endeavour to earn, beg, or steal their daily bread.THE AUTHORS.

Smith and Thompson’s study was published as the book Street Life in London.

Chapter one set the tone.

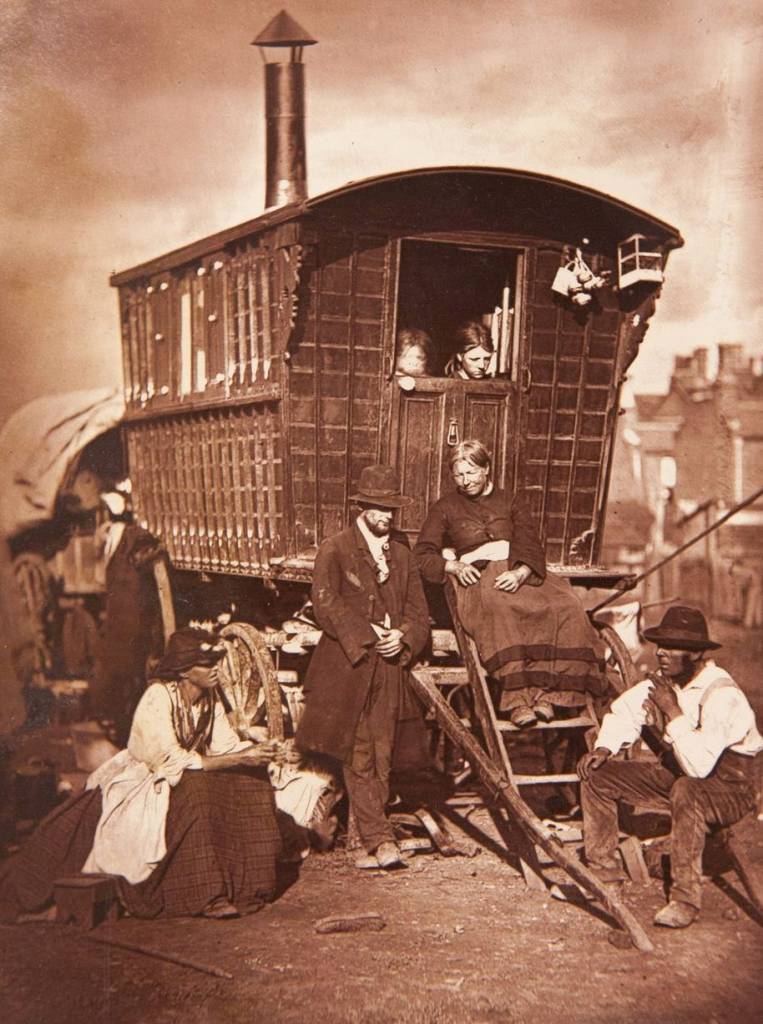

LONDON NOMADES.

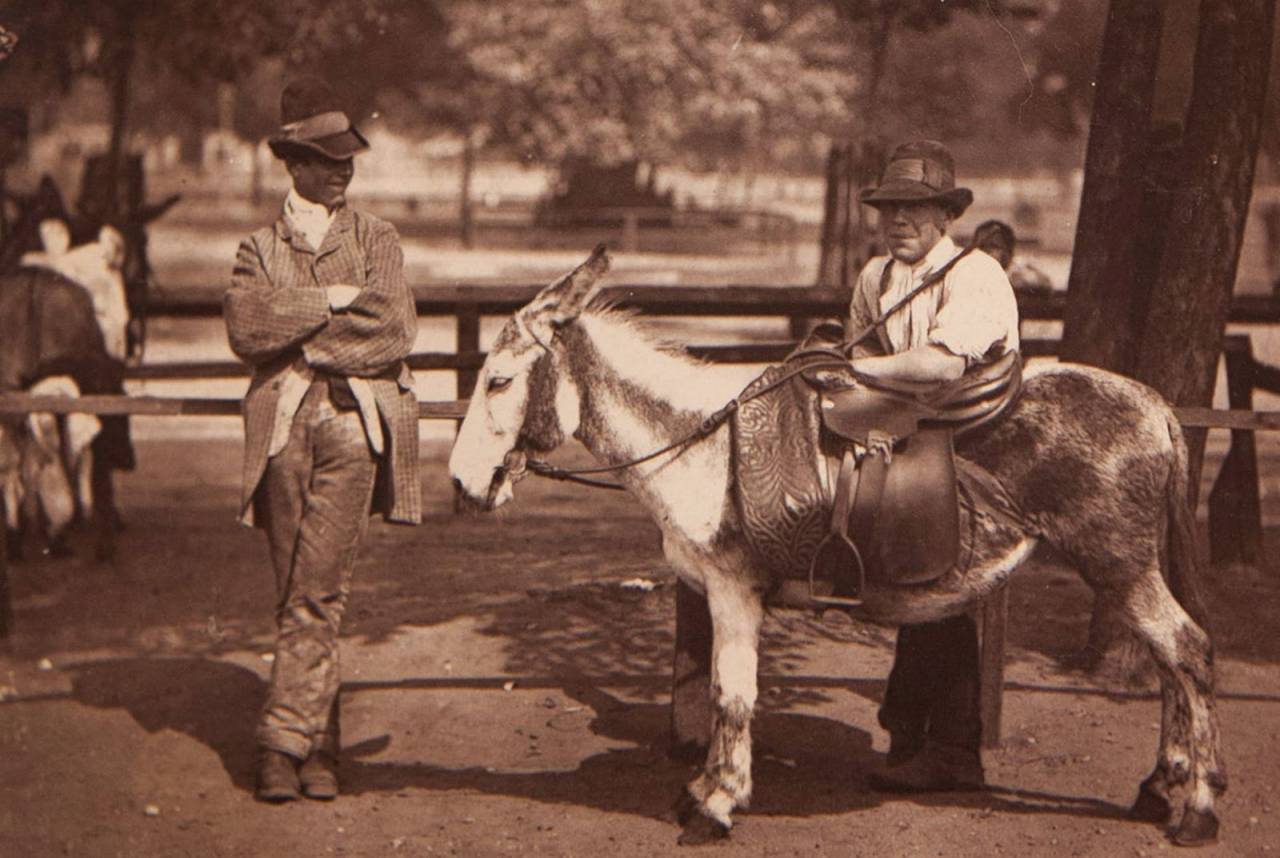

In his savage state, whether inhabiting the marshes of Equatorial Africa, or the mountain ranges of Formosa, man is fain to wander, seeking his sustenance in the fruits of the earth or products of the chase. On the other hand, in the most civilized communities the wanderers become distributors of food and of industrial products to those who spend their days in the ceaseless toil of city life. Hence it is that in London there are a number of what may be termed, owing to their wandering, unsettled habits, nomadic tribes. These people, who neither follow a regular pursuit, nor have a permanent place of abode, form a section of urban and suburban street folks so divided and subdivided, and yet so mingled into one confused whole, as to render abortive any attempt at systematic classification. The wares, also, in which they deal are almost as diverse as the families to which the dealers belong. They are the people who would rather not be trammelled by the usages that regulate settled labour, or by the laws that bind together communities.

The class of Nomades with which I propose to deal makes some show of industry. These people attend fairs, markets, and hawk cheap ornaments or useful wares from door to door. At certain seasons this class “works” regular wards, or sections of the city and suburbs. At other seasons its members migrate to the provinces, to engage in harvesting, hop-picking, or to attend fairs, where they figure as owners of Puff and Darts, “Spin em rounds,” and other games. Their movements, however, are so uncertain and erratic, as to render them generally unable to name a day when they will shift their camp to a new neighbourhood. Changes of locality with them, are partly caused by caprice, partly by necessity. At times sickness may drive them to seek change of air, or some trouble comes upon them, or a sentimental longing leads them to the green lanes, and budding hedge-rows of the country. As a rule, they are improvident, and, like most Nomades, unable to follow any intelligent plan of life. To them the future is almost as uncertain, and as far beyond their control, as the changes of wind and weather.

London gipsies proper, are a distinct class, to which, however, many of the Nomades I am now describing, are in some way allied. The traces of kinship may be noted in their appearance as well as in their mode of life, although some of them are as careful to disclaim what they deem a discreditable relationship as are the gipsies to boast of their purity of descent from the old Romany stock.

The accompanying photograph, taken on a piece of vacant land at Battersea, represents a friendly group gathered around the caravan of William Hampton, a man who enjoys the reputation among his fellows, of being “a fair-spoken, honest gentleman.” Nor has subsequent intercourse with the gentleman in question led me to suppose that his character has been unduly overrated. He had never enjoyed the privilege of education, but matured in total ignorance of the arts of reading and writing.

This I found to be the condition of many of his associates, and also of other families of hawkers which I have visited.

William Hampton is, for all that, a man of fair intelligence and good natural ability. But the lack of education other than that picked up in the streets and highways, has impressed upon him a stamp that reminded me of the Nomades who wander over the Mongolian steppes, drifting about with their flocks and herds, seeking the purest springs and greenest pastures.

He honestly owned his restless love of a roving life, and his inability to settle in any fixed spot. He also held that the progress of education was one of the most dangerous symptoms of the times, and spoke in a tone of deep regret of the manner in which decent children were forced now-a-days to go to school. ” Edication, sir Why what do I want with edication? Edication to them what has it makes them wusser. They knows tricks what don’t b’long to the nat’ral gent. That’s my pinion. They knows a sight too much, they do! No offence, sir. There’s good gents and kind arted scholards, no doubt. But when a man is bad, and God knows most of us aint wery good, it makes him wuss. Any chaps of my acquaintance what knows how to write and count proper aint much to be trusted at a bargain.”

Happily this dread of education is not generally characteristic of the London poor, although, at the same time, it is shared by many men of the class of which William Hampton is a fair type.

While admitting that his conclusions were probably justified by his experience, I caused a diversion by presenting him with a photograph, which he gleefully accepted. “Bless ye!” he exclaimed, “that’s old Mary Pradd, sitting on the steps of the wan, wot was murdered in the Borough, middle of last month.”

This was a revelation so startling, that I at once determined to make myself acquainted with the particulars of the event. The story of the mysterious death of Mary Pradd, however, will hardly bear repeating in detail. She was the widow of a tinker named Lamb, and had latterly taken to travelling the country with two men, one of them is said to have been of gipsy origin and very well known in Kent Street.The photograph was taken some weeks previous to the event. The deceased was spending an afternoon with her friends at Battersea, when I chanced to meet them and obtained permission to photograph the group. It was on the 18th of November last that the inquest was held concerning this unfortunate woman, at the workhouse, Mint Street. Mary Pradd was fifty-five years old at the time, and her death was reported as involving grave suspicion. A woman named Harriet Lamb gave evidence to the effect that deceased was her mother, the widow of a tinker, and lived with Edward Roland, at 40, Kent Street, Borough. She gave way occasionally to drink, but the witness had seen her alive and well, though not sober, between two and three on the previous day. Mary Pradd was in the habit of travelling through the country with a man named Gamble and with Roland.

Witness had seen her mother strike the latter, but had never seen Roland illtreat her.

Susan Hill, 40, Kent Street, deposed to hearing a noise early in the morning of Thursday, and to being subsequently called up by a woman to the deceased’s room, where she found her dressed, lying on her back, dead on the floor, and the two men dressed, and lying asleep on the bed.

Caroline Brewington, with whom Gamble lived, gave evidence that the men had been drinking together during the day, and finding that Gamble did not return, she ~vent to fetch him about midnight, and found the scene as described.

Roland and Gamble, who had been taken into custody on suspicion of having caused the death of the woman, pleaded total ignorance of the whole circumstances.

The medical evidence showed that she had died from hemorrhage, and that there was one external wound on her person.The jury returned a verdict, “That the deceased died from injuries, but that there was not sufficient evidence to show how such injuries were caused.”

The poor woman who met her end in so mysterious a manner had in life the look of being a decent, inoffensive creature. Clean and respectable in her dress, she might in her youth have been even of comely appearance, but now she wore the indelible stamp of a woman who had been dulled and deadened by a hard life. One of her neighbours described her as “a well-conducted, comfortable-looking, old lady. But the life she led latterly sent her sadly to drink. I have often said to her, Mary, you should not give your mind to the drink so.”

Mary Pradd was evidently above the common run of these people, and, continued my informant, “She might have done well, for some travelling hawkers make heaps of money, but they never look much above the gutter. I once knew one, Old Mo, they called him I used to serve him with his wares, brushes, baskets, mats, and tin things; for these are the sort of goods I send all over the country to that class of people. Cash first, you know, with them. I would not trust the best of them, not even Mo, though he used to carry £9000 about with him tied up in a sack in his van. He is now settled at Hastings; he has bought property. Never saw a curiouser old man, and as for his father, he was worse than him, a rich old miser. Bought and sold chipped apples because they were cheap. Sat at a corner where he owned houses, and sold halfpenny-worths.

“He had untold ways of making money; lending it, I think. Mo once bet me he had more old sovereigns, guineas, and half-guineas than any man living, unless a dealer.

“One thing I thought would have killed him. He was once robbed of £1400 in gold and silver, by two men, who sent the boy watching the van off to buy apples. They took as many bags of money out of the sack as the two could carry.

“I have lost the run of him now.”

Such is the story of Mo, as it was related to me, and I am further assured that most of these wanderers make money, or have the chance of doing so, their trade expenses being only nominal and their profits frequently large. I myself have been introduced to a man of this class in London, who owns houses and yet lives in his van pursuing his itinerant trade in the suburbs.

The dealer in hawkers’ wares in Kent Street, tells me that when in the country the wanderers “live wonderful hard, almost starve, unless food comes cheap. Their women carrying about baskets of cheap and tempting things, get along of the servants at gentry’s houses, and come in for wonderful scraps. But most of them, when they get flush of money, have a regular go, and drink for weeks; then after that they are all for saving.

“They have suffered severely lately from colds, small pox, and other diseases, but in spite of bad times, they still continue buying cheap, selling dear, and gambling fiercely.

Declining an invitation to “come and see them at dominoes in a public over the way, I hastened to note down as fast as possible the information received word for word in the original language in which it was delivered, believing that this unvarnished story would at least be more characteristic and true to life.J.T.

THE OLD CLOTHES OF ST. GILES.

BUT few articles change owners more frequently than clothes. They travel downwards from grade to-grade in the social scale with remarkable regularity; and ·then, strange to say, spring up once more with new life, to be worn again by the wealthy….

The accompanying photograph represents a second-hand clothes shop in a narrow thoroughfare of St. Giles, appropriately called Lumber Court, where several similar tradesmen are grouped together, all dealing in old clothes and furniture of a most varied and dilapidated description. It is here that the poorest inhabitants of a district, renowned for its poverty, both buy and sell their clothes. During the time I was prosecuting my inquiries in the court, I noticed, however, a greater disposition on the part of its frequenters to sell than to buy. First, one woman came to dispose of her husband’s tools, than another wanted to sell her children’s clothes, and a third sought to raise money on a couple of nickel forks. These offers were for the most part refused by the dealer, who with stolid countenance announced that she was “not buying anything to-day;” thereupon, the articles were proffered at a great reduction, but, being of little value, were generally refused. Sometimes, amid the rubbish accumulated in these shops, some rare articles of virtu may be found; the dealers themselves often ignoring the worth of the treasure which has accidentally fallen into their hands. Connoisseurs are therefore constantly sauntering past for the purpose of discovering objects of this description. As a rule, however, the bulk of the business transacted, relates to the sale of clothes, and it is at such shops that the majority of those individuals who earn a promiscuous livelihood in the streets of London, succeed in clothing themselves for a minimum outlay. Few persons have a better insight into the hard side of life than the dealers in old clothes; for it is to them that are brought the refuse apparel which has been rejected by the pawnbrokers as unsuitable guarantee for even the smallest loan. Indeed, the influx of rubbish to these shops is so considerable, that it has been worth while to organize a regular system for sorting and removing such refuse. Thus, two or three times in a week, a man comes to Lumber Court, and purchases from the shops all the old tin they have been able to collect. Worn-out tin kettles and coal-scuttles are still of use. The best pieces can be cut out, covered with cheap black varnish, and sold to trunk-makers to protect the edges and corners of trunks. If the tin is not strong enough for any mechanical purpose, the chemist can combine it with other substances, and thus form salts that are of great value to the dyer and ink-maker…The dealer whose portrait is before the reader cannot boast of a large business. She had been unfortunate in previous speculations, and illness had also crippled her resources, so that her stock is limited, and her purchasing power still more restricted. Under these circumstances she declared that on an average she was unable to make more than thirty shillings a week net profit, which is a very low estimate for persons engaged in this business. I could not help concluding, however, that ignorance was to some extent a bar to greater success. Her knowledge of the value of some old books and some wretched oil paintings was of the vaguest description, and she confessed to having sold a quarto law book, published during the reign of James I., for half-a-crown, which she afterwards discovered could not be bought back for less than two guineas. Such mistakes on the part of dealers are of frequent occurrences and the opposite extreme may also be noted. It often happens that they ignorantly assume that some ornament is more scarce or has a far higher value than is really the case; and, therefore, it was with some bitterness of feeling that the dealer in question remarked, “There are such a number of persons about who know the value of things.” Nevertheless, it would not be fair on my part to conclude this criticism without adding, that if the dealer was ignorant in matters relating to literature and fine arts, she was at least master in the art of keeping her home clean, even under the most difficult circumstances. As a rule, second-hand clothes shops are far from distinguished for their cleanliness, and are often the fruitful medium for the propagation of fever, smallpox, &c. In this case, however, the floor was well washed, the shop carefully dusted, the goods kept in order of merit, and the grate resplendent in all the glory of unstinted black lead. A door at the back admitted a thorough current of air, and the presiding genius of all this adroit organization seemed fully alive to the importance of good ventilation. Perhaps these rare qualities explain the fact that trade is slack with her. Cleanliness is essentially distasteful to, and is even considered “stuck up,” by a large section of the population.

A. S.

CAST-IRON BILLY.

“FORTY-THREE years on the road, and more,” said Cast-iron Billy; “and, but for my rheumatics, I feel almost as ‘ale and ‘earty as any gentleman could wish. But I’m lost, I’ve been put off my perch. I don’t mind telling of you I’m not so andy wi’ the ribbons as in my younger days I was. Twice in my life I’ve been put off, and this finishes me. I’ll never hold the whip again that’s been in my hand these three and forty year, never! I can’t sit at ‘ome, my perch up there was more ‘ome to me than ‘anythink.’ Havin’ lost that I’m no no good to nobody; a fish out o’ water I be.”

William Parragreen, known as “Cast-iron Billy,” may be said to have commenced life with the whip in his hand. With an inborn aptitude for the profession he took to the road early. Whip in hand he mounted his father’s cab, and continued for some years to pilot the vehicle through the busy streets of London.

In the days when the Royal Mails ran from the Post Office, with their armed guards and passengers, prepared for long weary journeys, William was fired with the ambition to drive some more imposing conveyance than the old four-wheeler. At last his hopes were realized, and he commenced his career as omnibus driver on the London roads. This event was indelibly fixed in his memory as it happened in 1834, when the old Houses of Parliament were destroyed by fire.

THE “CRAWLERS.”

HUDDLED together on the workhouse steps in Short’s Gardens, those wrecks of humanity, the Crawlers of St. Giles’s, may be seen both day and night seeking mutual warmth and mutual consolation in their extreme misery. As a rule, they are old women reduced by vice and poverty to that degree of wretchedness which destroys even the energy to beg. They have not the strength to struggle for bread, and prefer starvation to the activity which an ordinary mendicant must display. As a natural consequence, they cannot obtain money for a lodging or for food. What little charity they receive is more frequently derived from the lowest orders. They beg from beggars, and the energetic, prosperous mendicant is in his turn called upon to give to those who are his inferiors in the “profession.” Stale bread, half-used tea-leaves, and on gala days, the fly-blown bone of a joint, are their principal items of diet. A broken jug, or a tea-pot without spout or handle, constitutes the domestic crockery. In this the stale tealeaves, or, perhaps, if one of the company has succeeded in begging a penny, a halfpenny-worth of new tea is carefully placed; then one of the women rises and crawls slowly towards Drury Lane, where there is a coffee-shop keeper and also a publican who take compassion on these women, and supply them gratuitously with boiling water. Warm tea is thus procured at a minimum cost, and the poor women’s lives prolonged. But old age, and want of proper food and rest, reduces them to a lethargic condition which can scarcely be preferable to death itself…

The crawler, for instance, whose portrait is now before the reader, is the widow of a tailor who died some ten years ago. She had been living with her son-in-law, a marble stone-polisher by trade, who is now in difficulties through ill-health. It appears, however, that, at best, “he never cared much for his work,” and innumerable quarrels ensued between him, his wife, his mother-in-law, and his brother-in-law, a youth of fifteen. At last, after many years of wrangling, the mother, finding that her presence aggravated her daughter’s troubles, left this uncomfortable home, and with her young son descended penniless into the street. From that day she fell lower and lower, and now takes her seat among the crawlers of the district. Her young son is not only helpless, but troubled with unjustifiable pride. He has pawned his clothes, is covered with rags, but still scorns to sell matches in the street, and is accused of giving himself airs above his station!

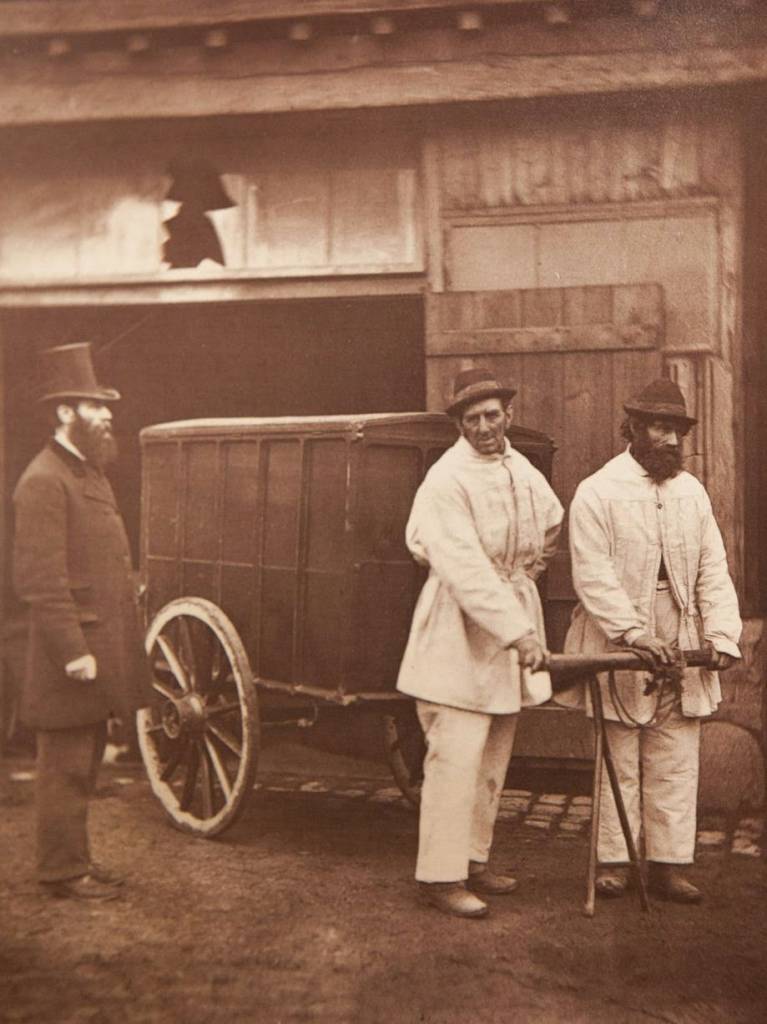

PUBLIC DISINFECTORS.

WHILE reducing the general death-rate, our recent sanitary legislation has called into existence a class of men who must of necessity be daily exposed to the gravest dangers. To the list of men who, by reason of their avocations, constantly face death to save us from peril, we must add the public disinfectors….

The accompanying photograph has been taken in the yard adjoining the Vestry Hall, close by Ebury Bridge, and the familiar countenance of Mr. Dickson, the Inspector of Nuisances for the Parish or Union of St. George’s, Hanover Square, will be readily recognized by all who are well acquainted with this district. The group is gathered in front of the out-house where the disinfecting-oven is situated. This is simply an oblong iron box, which can be heated by a gas apparatus, till the atmosphere within reaches 280 degrees. This intense dry heat cannot spoil the materials placed inside, and has been proved, by innumerable experiments, to be the surest method of killing the germs of zymotic disease. Boiling for about twenty minutes would be equally effective, but we cannot boil furniture. Unless some such method is adopted, the microzymes may live for an indefinite period; indeed, the germs of scarlet fever can live in woollen materials for several years. Mrs. C. M. Buckton mentions in her popular Lectures on the Laws of Health a case of a child who died of this fever. Her favourite doll was put away in a woollen dress. Three or four years later, a cousin came to pay a visit at the house, and the mother, to amuse the little girl, brought out the doll, which had not been touched since her own child’s death. A week had, however, hardly elapsed since this incident, when the little visitor was in her turn seized with the scarlet fever. The doll evidently should have been disinfected, even at the risk of destroying the symmetry of its waxen features.

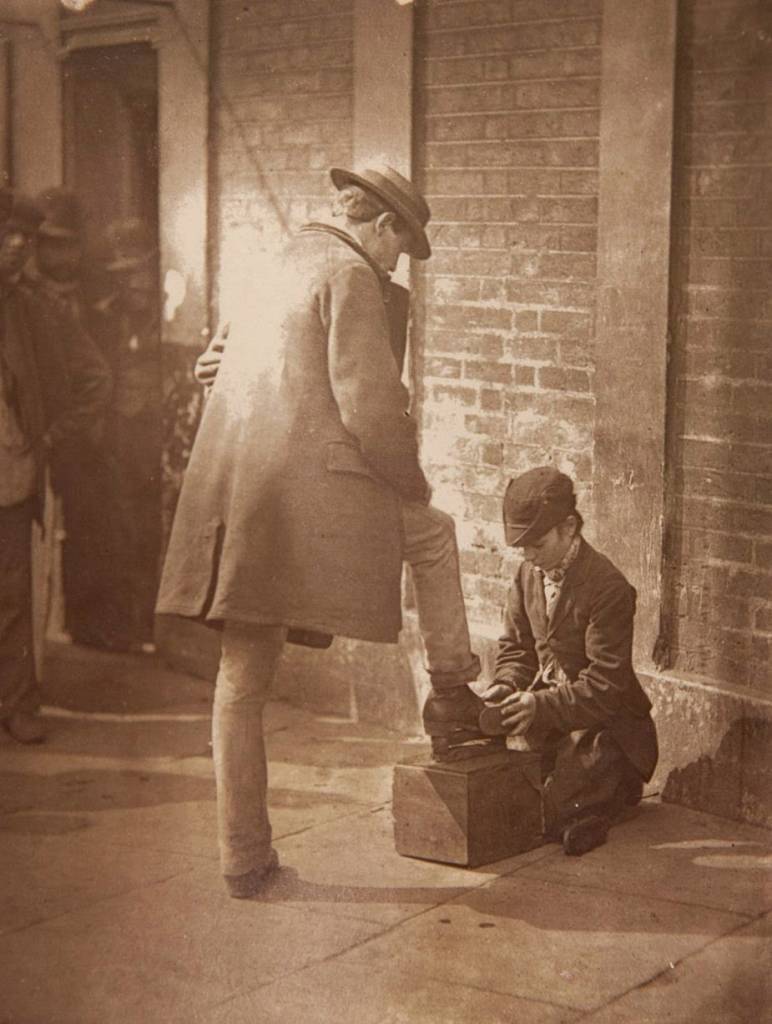

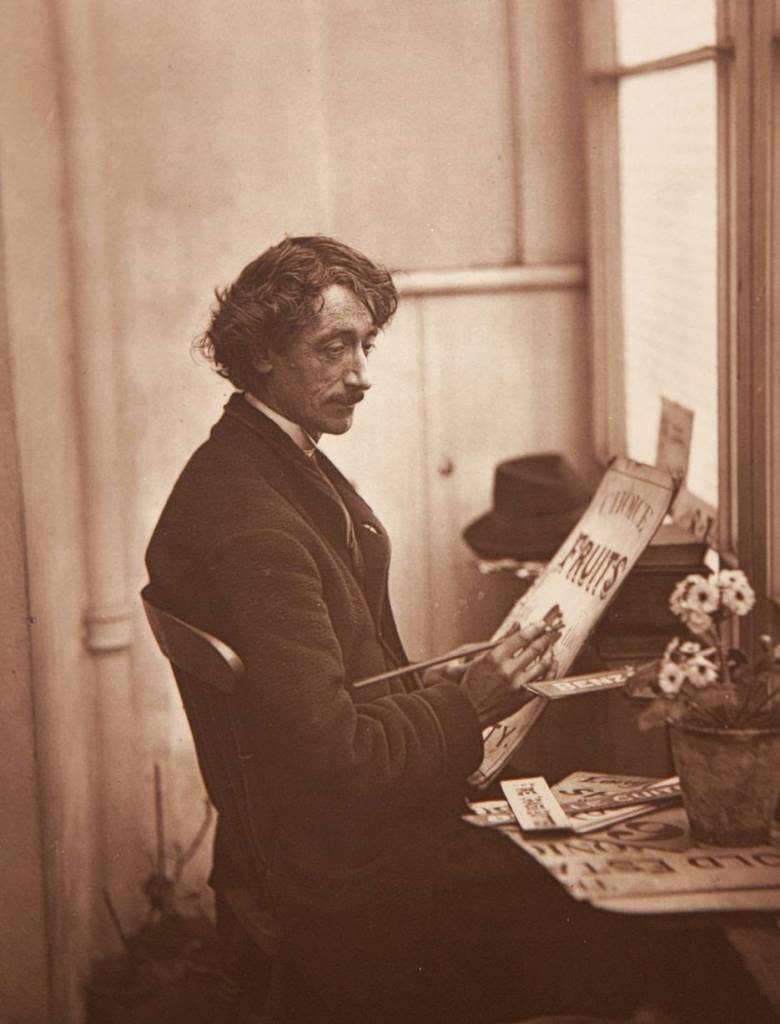

THE DRAMATIC SHOE-BLACK.

JACOBUS PARKER, Dramatic Reader, Shoe-Black, and Peddler, is represented in the accompanying photograph standing at his accustomed “pitch.” Although the career of Parker has been clouded, and his life-story is one of struggle and disappointment, yet he has fought the battle bravely, and, as a veteran, is not without his scars. “There is one thing I am proud of” said Parker, one day; “I am near three-score years and ten, have fought life’s battle and won, and will carry with me to the end its chief prizes – a hale heart and a contented mind.” “Greed of gain, sir, has never been my motto. It is but a poor object to fill up every nook and cranny of a human heart from boyhood to old age, as it does with many.” Again, in his own words, ” I have always advocated temperance and detested drunkenness.* (*The quotations were jotted down at they were uttered) ‘In my youth I never did apply hot and rebellious liquor to my blood, nor did, with unbashful forehead, woo the means of weakness and debility.’ Ah, sir, I have seen wine make woeful wrecks of men and women too, recalling the powerful lines, ‘Oh! thou invisible spirit of drink, if thou hast no other name to go by, let us call thee Devil.’

“Rumty,” to use the cognomen by which Parker is known to a wide circle of poor friends and patrons, made a fair start in life. His father, he assures me, was a sort of private gentleman having some means at his disposal. One brother served his country in the army, another followed the law as a profession, while our hero was apprenticed to a wholesale stationer in the city, his father paying a premium to his master. Beyond this Parker appears to have received no further pecuniary aid, so that when he completed his term of apprenticeship he had to make his way in the world single-handed. At this point in his career he had a number of business associates, but the ties that bound them together were soon broken, and their paths diverged. Some he lost sight of, others he accounted least likely to succeed carved out their fortunes for themselves while he became a journeyman vellum-binder. In this capacity he obtained work in different parts of England, and at last succeeded in getting a post as vellum-binder in the Stationery Department of the Treasury Office. He held this position under the Government contractor for nearly twenty-two years: but to continue our narrative in his own words:-

“At this time, I may say, I lay in clover. Like all gentlemen who labour under the wings of Government, I enjoyed short hours, and a very fair salary. My hours were from about ten to four. I cannot say I was over provident, otherwise I might have saved a trifle of money. I strove, however blindly, to make the most of the present, by devoting my leisure to the drama. I became acquainted with a distinguished prompter in one of the London theatres, and forthwith entered upon an after-hour dramatic career, while still in the Treasury in 1846. I appeared in ‘Green Bushes’ and ‘St. George and the Dragon’ at the Adelphi, as a super, of course; but I soon rose to be St. Philip of Spain in’ St. George and the Dragon.’ I must tell you I had previously appeared in Shakspearian characters at other theatres. But in Othello I came totally to grief, and quitted the stage for a term, until, indeed, I made the acquaintance of the prompter. Another painful circumstance occurred. I had risen unaided to perform Hamlet’s ghost. It was a packed house, and somehow I made a fatal blunder in pronouncing one word. In place of saying ‘The glow-worm shows the matin to be near,’ I said ‘The glow-worm shows the mating to be near.’ This was my first and last appearance as ghost, and you may be sure I got full credit for this original rendering of Shakspeare. I had my successes, too, I remember; one evening when the ‘Mysterious Stranger’ was on, the gentleman who had to play the corporal on duty failed to appear. The manager was in a fix, until, at the last moment, I volunteered for his part. I had only a few words to say in addressing the dealer in forged passports, but it was a success. After that I became a dramatic reader, got myself up in ‘Goldsmith’s Deserted Village,’ and, in the costume of the period, personating Oliver himself. This brought me before many literary circles in different parts of London and its suburbs, but the pay was little better than that of a super.

“Suddenly I fell ill, lost the sight of my left eye, and had to leave my regular work at the Treasury. After partial recovery I went to Liverpool, to try my fortune there; but found no demand for my services as a workman or as a reader. Coming again to London I hoped to join my son, who was a bookbinder; this, too, proved a failure, as he, poor fellow, had a wife and young family to support. I felt I was a burden to him, and cleared out. Age, poor health, and feeble sight told on me woefully; there was work for younger and stronger men, and my one-sided experience in the Treasury had done me no good as a workman. At last, sir, from sheer necessity, I drifted into Lambeth workhouse. I have nothing to say against such public asylums; they are a great boon to those who cannot help themselves, and many a poor soul in this city would be in a sad plight but for their aid. It galled my proper pride, however, and it is painful for a man who has had anything like decent training to have to herd with worthless, profligate, and abandoned paupers. When I regained my strength I determined to try to earn a living by reading and reciting, as you will see from this card.

The card in question was inscribed with the name Jacobus Parker, Dramatic Reader, accompanied by a quotation from the Parochial Critic, which ran thus:-“June 6th, 1871.

“An inmate of Lambeth Workhouse, Jacobus Parker, well known to the guardians, has taken his discharge, and is trying to earn a living by reciting portions of Shakspeare’s plays. He has an excellent voice, capable of considerable modulation and expression. He is passing under the appellation of Jacobus Parker.”

“Although,” continued Parker, “I was dubbed by my admirers, ‘William Shakspeare,’ I did not confine myself to the works alone of the great dramatist, but recited as well portions from Burns, Thomson, Bloomfield, &c. My chief successes were in the ‘Carpenters’ Arms,’ William Street, Kennington, where I have entertained many a gathering of my supporters. I still have what I call my Shakspearian cloak, and can give you, old as I am, a Shakspearian evening whenever you choose.

“Now, I am stationed as a shoe-black, at your service, armed with a peddler’s licence. I get along fairly well. My pride, perhaps, stands in my way; and were it not for the unsought kindness of my landlady I would fair badly at times.

“I occupy a little room, a garret, all my own, for which I pay half-a-crown weekly. I suffer some annoyance from the brainless practical jokes of a pack of loafers, who have respect neither for old age nor poverty. To tell you the truth, when I think of my past and present, I am surprised to find myself so happy and contented. My only care is to earn enough to carry me through to the close of each day. I have no bills to meet-no taxes save my licence – no burdens except old age, and that hangs lightly on my shoulders. I quite endorse the sentiment, ‘True hope ne’er tires, but mounts on eagle’s wings, kings it makes gods, and meaner creatures kings.’ Thank God, mean as I am, I am blessed with that princely inheritance, hope, and with what the wealth of kings cannot secure, contentment.

“I have not told you that I was mainly indebted for my rescue from the Workhouse to the kindness of the Ex-Premier, Mr. Gladstone. I wrote to him, and he replied at once to me, a pauper, in a manner so kind that ‘it brought my heart to my mouth.’ He also sent his secretary to inquire into my case, and the result was a prompt grant of /10 from the Queen’s bounty. This started me in the street, where I have since continued to earn a living.

“A shilling a day is about my average net profit; on Sundays I make a trifle over. Sunday morning brings me sundry boots to shine. But if I could get a half-crown reading once a week, I would gladly cut the Sunday work. I am not above cleaning Christian boots on Sunday, yet I would fain rest from my labours.

“Should any of your readers want a Shakspearian evening, I will get my cloak repaired, and rest on the Lord’s Day.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.