In 1885, Wilson Alwyn Bentley (aka Snowflake Bentley, the Snowflake Man) attached a microscope to a bellows camera at his farm in Bentley Jericho, Vermont, and took the first photograph of a single snowflake. Bentley wrote in 1925:

“Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost.”

For a February 1925 issue of The American Magazine, writer Mary B. Mullet sought out Bentley and what she called his Dream of Beauty:

My mecca was a farm about six miles away, a farm where lives a man of extraordinary passion. For almost sixty years — that is, practically his whole life — he has followed what I cannot help calling a Dream of Beauty.

I have found that his name, W. A. Bentley, doesn’t seem to mean anything to most people. But if I call him “the snowflake man” it often brings a quick recognition. Some of you may have seen reproductions of his marvelous photographs of snowflakes–snow crystals, as he prefers to call them.

Bentley told her:

“I was born in 1865, and I can’t remember the time I didn’t love the snow. I never went to school until I was fourteen years old. My mother taught me at home. All that I am, or that I ever shall be, I owe to her. She had been a school teacher before she married my father, and she instilled in me her own love of knowledge and of the finer things of life. She had books, including a set of encyclopedias. I read them all.

“And it was my mother who made it possible for me, at fifteen, to begin the work to which I have devoted my life. She had a small microscope which she had used in her school teaching. When the other boys of my age were playing with popguns and slingshots, I was absorbed in studying things under this microscope: drops of water, tiny fragments of stone, a feather dropped from a bird’s wing, a delicately veined petal from some flower.

Bentley and his mother in an early snow, around 1890. – CREDIT WILSON A. BENTLEY / UVM SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Via

“But always, from the very beginning, it was the snowflakes that fascinated me most. The farm folks, up in this north country, dread the winter; but I was supremely happy, from the day of the first snowfall–which usually came in November–until the last one, which sometimes came as late as May.

“Under the microscope, I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty; and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated., When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind.

“I became possessed with a great desire to show people something of this wonderful loveliness, an ambition to become, in some measure, its preserver. I had read of cameras that photographed through microscope. If I could have such an apparatus, I believed I could make permanent records of snow crystals.”

“When I was seventeen years old, my mother persuaded my father to buy me a camera and microscope which I have developed into the apparatus I am still using. I cost, even then, one hundred dollars. You can imagine, or perhaps you cannot, unless you know what the average farmer is like, how my father hated to spend money on what seemed to him a boy’s ridiculous whim. But I don’t think my love of beauty made me a worse farmer. This was only a ten-cow dairy farm when my father died My brother and I made it a twenty-cow farm–and I did my share of the work.

“I am still a farmer, although my nephew runs the place on shares. But I do a good deal toward improving it. I wish I could show you one of my pastures up on the hill. You would find great cairns of rocks which I made last summer, clearing them out of the field and so making it more valuable.”

On 15 January 1885, Bentley obtained the first photomicrographs ever taken of an ice crystal:

“I never shall forget the disappointments that followed my early attempts. Here I was, with this expensive apparatus which had been given to me so reluctantly. I had been sure that I could do wonderful thins with it, but I failed over and over again. I could get nothing but a faint image on the plate, so dim that it was practically worthless.

“If there had only been someone to explain what was wrong. but away off here on a farm there was nobody to help me. Again and again I failed. The winter slipped away and I was almost heartbroken. But by the next season I had found the secret of my trouble. I began to use a very small ‘stop’–a thin plate, with a tiny opening to shut out most of the light. With this, and a longer exposure, I got a clear image of greater intensity.

“The day that I developed the first negative made by this method, and found it good,” said Bentley with genuine emotion, “I felt almost like falling to my knees beside that apparatus. I knew then that what I had dreamed of doing was possible. It was the greatest moment of my life.”

“That was in 1884., when I was nineteen years old, but it was almost fourteen years before my work received any recognition. It was very discouraging. I knew I had something to give to the world–but no one seemed to care for it. I had very little money. I had to deny myself in every possible way in order to buy materials I needed for my pictures. I was all the time paying out–and not getting a cent in return.

“The first recognition came from Professor Perkins of the University of Vermont. He saw my pictures, bought some to use with his classes, and in 1898 helped me write my first article. Since then, many of the photographs have been reproduced in scientific publications, both in this country and in Europe.”

Bentley revealed how he came to take pictures of snowflakes in a 1922 article for Popular Mechanics Magazine, Vol. 37, 309-312. It’s a longish and worthwhile read, rich in technical nous brought on by trial, error, experiment and perseverance. Through it we glimpse Bentley’s dedication, skill and innovation to achieve his lifelong ambition:

“I became possessed with a great desire to show people something of this wonderful loveliness, an ambition to become, in some measure, its preserver.”

In his lifetime, Wilson A. Bentley photographed 5, 381 crystals. He explained:

Every snowflake has an infinite beauty which is enhanced by knowledge that the investigator will, in all probability, never find another exactly like it. Consequently, photographing these transient forms of Nature gives to the worker something of the spirit of a discoverer. Besides combining her greatest skill and artistry in the production of snowflakes, Nature generously fashions the most beautiful specimens on a very thin plane so that they are specially adapted for photomicrographical study.

The photographing of snowflakes, although quite delicate work, can hardly be called difficult, although some hardships attend it, because the work must all be done in a temperature below freezing, and under conditions of much physical exposure. The temperature at which photography is possible depends somewhat upon the thickness of the crystals; this varies greatly from time to time, and depends upon whether the temperature is rising from an intense degree of cold or falling from a point above freezing. If rising after a cold snap, photographing can often be continued until actual thawing commences.

Of course, location is everything in this work, and no one except those living in arctic climates or in regions having long and severe winters, can accomplish much. Generally speaking, the western quadrants of widespread storms or blizzards furnish the most beautiful and perfect forms. At such times the wind is usually westerly or northerly, with the barometer standing at 29.6 to 29.9 in. and slowing rising. The percentage of perfect crystals is likely to be larger when the snowfall is not too thick and heavy, with the crystals medium to small in size rather than large. The character of the snowfall often undergoes quite abrupt changes as a storm progresses.

The apparatus required for snowflake photography consists of a compound microscope, fitted with a joint that permits the instrument to be turned down horizontally, at right angles to its base, so that it can be coupled to a camera bellows by means of a light-tight connection. The microscope objectives are used alone, without the eyepiece. It is best to have several different objectives; 1/2, 3/4, and 3-in. combinations, which give magnifications of from 8 to 60 diameters (64 to 3,600 times), will serve well.

Ordinary daylight, coming through a window, is used for illuminating the crystal after it has been placed on a microscope slide, a tiny beam of light entering through the small aperture in the substage of the instrument. The apparatus is placed indoors, near by and facing a window. The room, the apparatus, and its accessories should always be away from any source of artificial heat, and at a temperature approximately that of the outside air. The necessary accessories are an observation microscope, a pair of thick mittens, microscope slides, a sharp-pointed wooden splint, a feather, and a turkey wing or similar duster; also, an extra focusing back for the camera, containing clear glass instead of the usual ground glass, with a magnifying lens attached; this is used for final focusing. A blackboard, about 1 ft. square, with stiff wire or metal handles at the ends, so that the hands will not touch and warm it, is used to collect the specimens. As it is necessary to cover the end of the microscope objective with a strip of black card, that takes the place of the usual camera shutter which controls the duration of exposure, it is necessary to fit two vertical rods at each side of the microscope tube to hold the card.

The snowflakes are caught on the blackboard as they fall, and examined by the naked eye or with the assistance of a hand magnifying glass. The feather duster is used to brush the board clean every few seconds, until two or more promising specimens alight upon it, when it is immediately removed indoors. From this point onward the photographer must work fast. The promising specimens are placed for a moment’s observation under the observation microscope. The removal of the snowflake from the board to the microscope slide is accomplished with the sharp-pointed splint, which is pressed gently against the face of the crystal until the latter adheres to it, so that it can be picked up and placed on the glass slide. Usually several crystals are placed together on a single slide, a momentary glance being given to each, and care taken while doing this not to breathe on the crystals. The utmost haste must be used, for a snow crystal is often exceedingly tiny, and frequently not thicker than heavy paper. Furthermore, once these bits of pure beauty are isolated, evaporation (not melting) soon wears them away, so that, even in zero weather, they last but a very few minutes.

When a desirable specimen is obtained, it is pressed flat against the glass with the edge of the feather and the slide inserted in the stage of the microscope on the camera stand, centered, roughly focused with the camera ground glass, then sharply focused with the clear-glass screen and magnifier, focusing on some tiny air tube near the center of the crystal. The plate holder is then inserted into the camera, the objective covered with the black card and the slide removed from the plate holder. The objective is then uncovered, and when the exposure, which may vary from 8 seconds to 100 or more, is deemed sufficient, the operation is reversed. Naturally enough, no rule for the length of exposure can be given, except that the greater the magnification, the longer the exposure should be.

The frail, feathery flakes are the most difficult to photograph, and it is always best to place five or six other crystals around the specimen, as this greatly retards the evaporation of the central one.

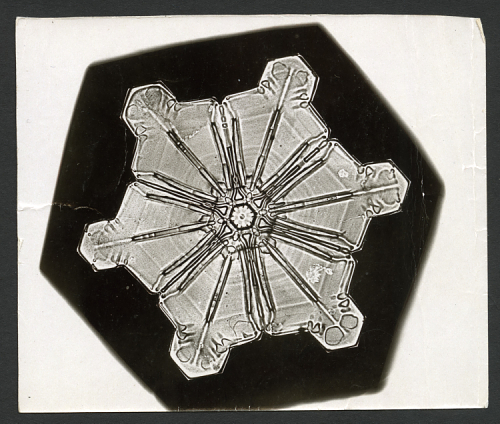

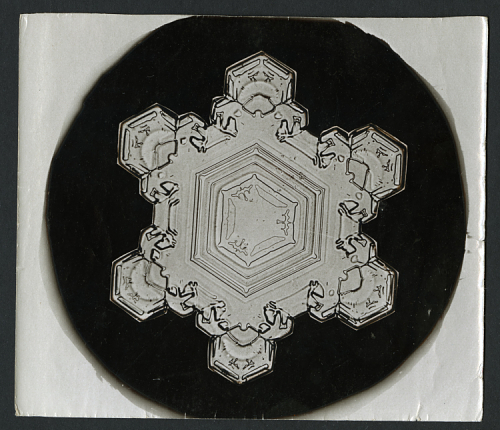

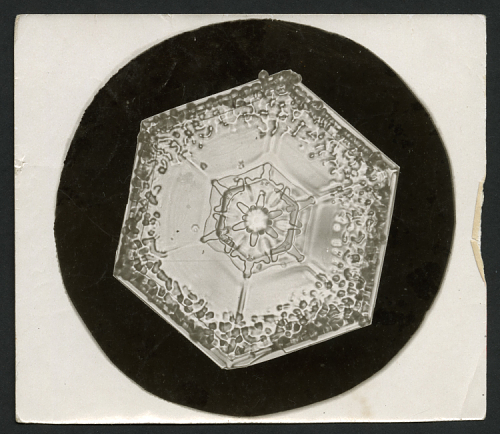

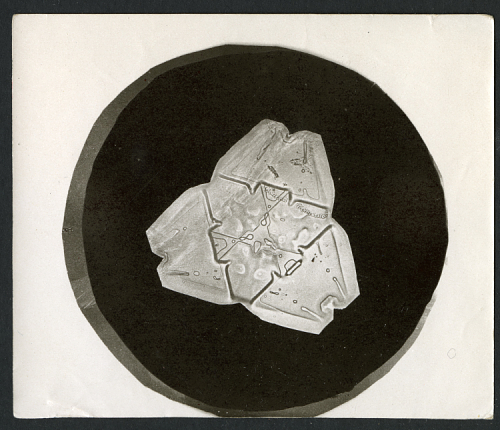

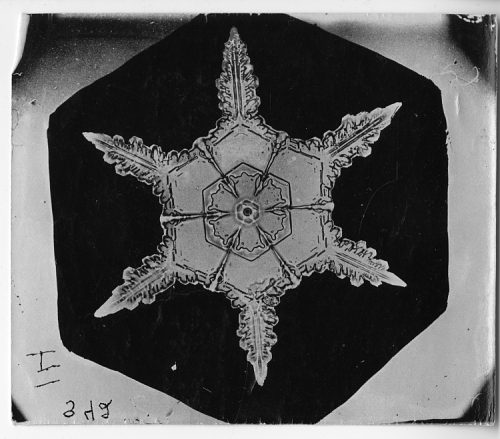

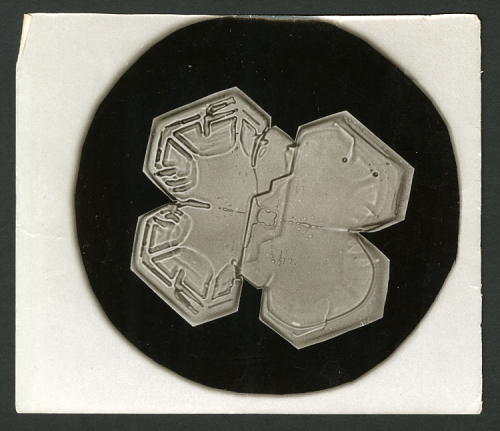

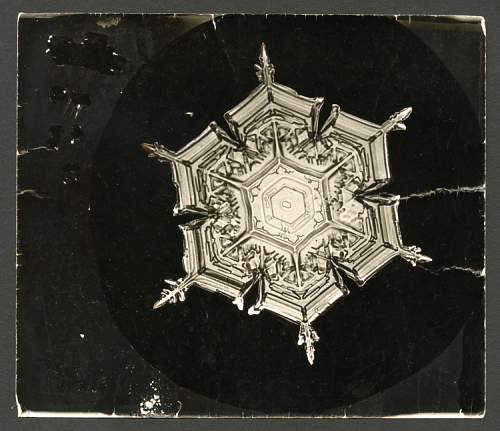

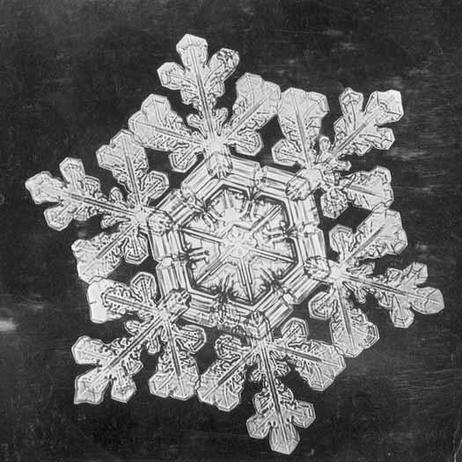

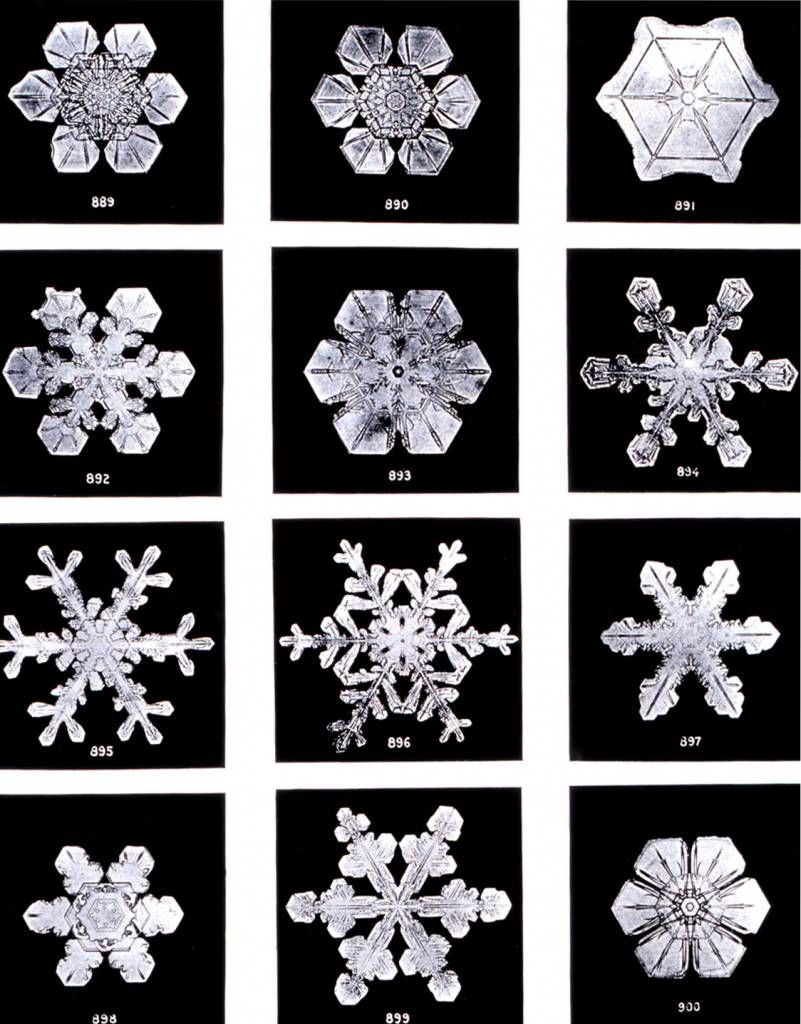

Wilson Bentley – Plate XIX of “Studies among the Snow Crystals … ” by Wilson Bentley, “The Snowflake Man.” From Annual Summary of the “Monthly Weather Review” for 1902.

When working from the rear of the camera, and the bellows extension is such as to make it impossible to reach the focusing screw on the microscope, an arrangement similar to that shown in the page illustration can be used. This consists of a cord that runs over a wheel on each side of the camera and around the focusing screw. No lens is required in the camera, the microscope furnishing the optical equipment for projecting the images onto the sensitized plates.

Having recorded the fleeting substance of the snowflakes on the photographic negative and brought out the image by development, the photographer discovers that the body of the snow crystal is so transparent, that it does not contrast enough with its background to make a print in which the form will stand out in relief. There is no purely photographic method for producing the white images against a dark background, and yet it is necessary to do so if the images are to be appreciated by most people, whose ideal of snow is that of immaculate whiteness. The only effective method of accomplishing this result is what is known among photographers as “blocking out.”

The negative is supported on an ordinary retoucher’s desk, which may be merely a piece of glass, arranged to hold the negative so that the image is illuminated by transmitted light. Then, with an etching knife or other fine, sharp-pointed tool, the operator proceeds to scrape away the emulsion around the outline of the crystal to leave it standing alone against a background of clear glass. This requires considerable patience, and often considerable time as well. In order to avoid irreparably spoiling the original negative, it is best not to alter it in any way, but to make a copy negative on which the actual blocking out is done. After the negative has been thus prepared, prints or lantern slides are made in the usual manner. Blocking out the negatives is done indoors, instead of outdoors as shown by the photograph, which was thus taken to get sufficient light to allow the exposure to be made.

Wilson Alwyn Bentley: February 7, 1865 – December 23, 1931.

On the morning he was laid to rest in the Jericho Center cemetery, it began to snow, leaving a dusting over the burial ground.

Images: In 1903 the ever-generous Bentley sent 500 prints of his snowflakes to the Smithsonian. They are now part of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Read more at the excellent SnowflakeBentley.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.