Hugh Hefner was thinking about breasts. He thought about breasts a lot. And pussy. Pussy and breasts was good but thinking about money was often better. He smoked his pipe and looked across the hotel lobby at the two young blondes by the swimming pool. It was his job to think about pussy and breasts. It was his job, his lifestyle choice. Everyone should have a lifestyle. Everyone should have choice. But now he had to think about movies. He had to think about movies a lot. He liked movies. He liked watching movies. He’d just produced one.

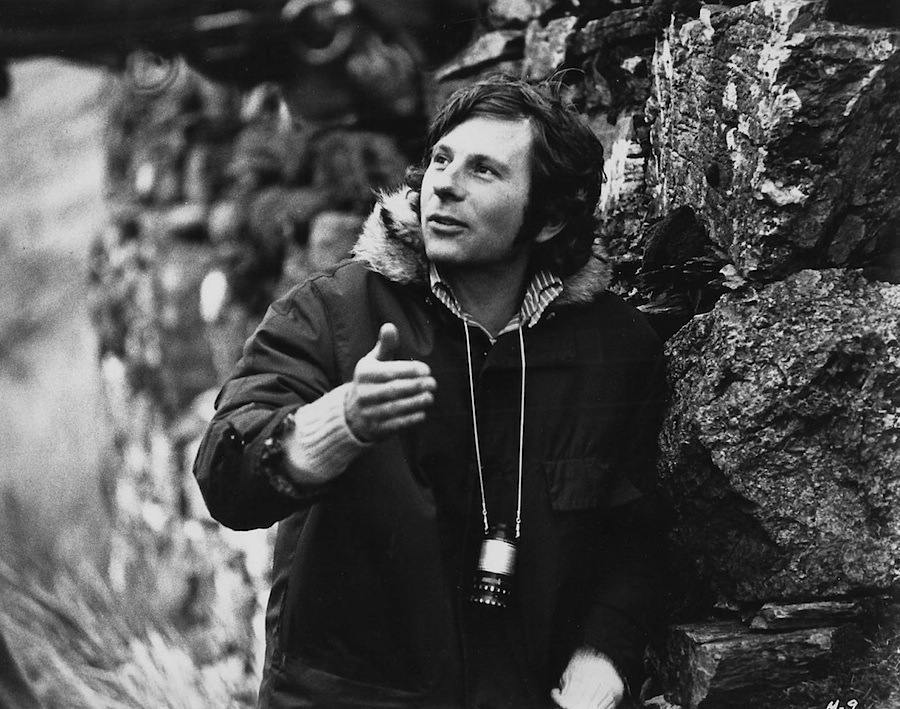

The director was Roman Polanski, the young kid everyone talked about in hushed tones because of what had happened to his wife. No one said it outright but they were all thinking it and he knew they were all thinking it—-what had he done to deserve this? Nothing. Polanski made a name for himself in Hollywood with that film about the Devil fucking Mia Farrow—-Rosemary’s Baby. Funny how it all came down to sex. Sex is the driving force on the planet—-why see it as an enemy?

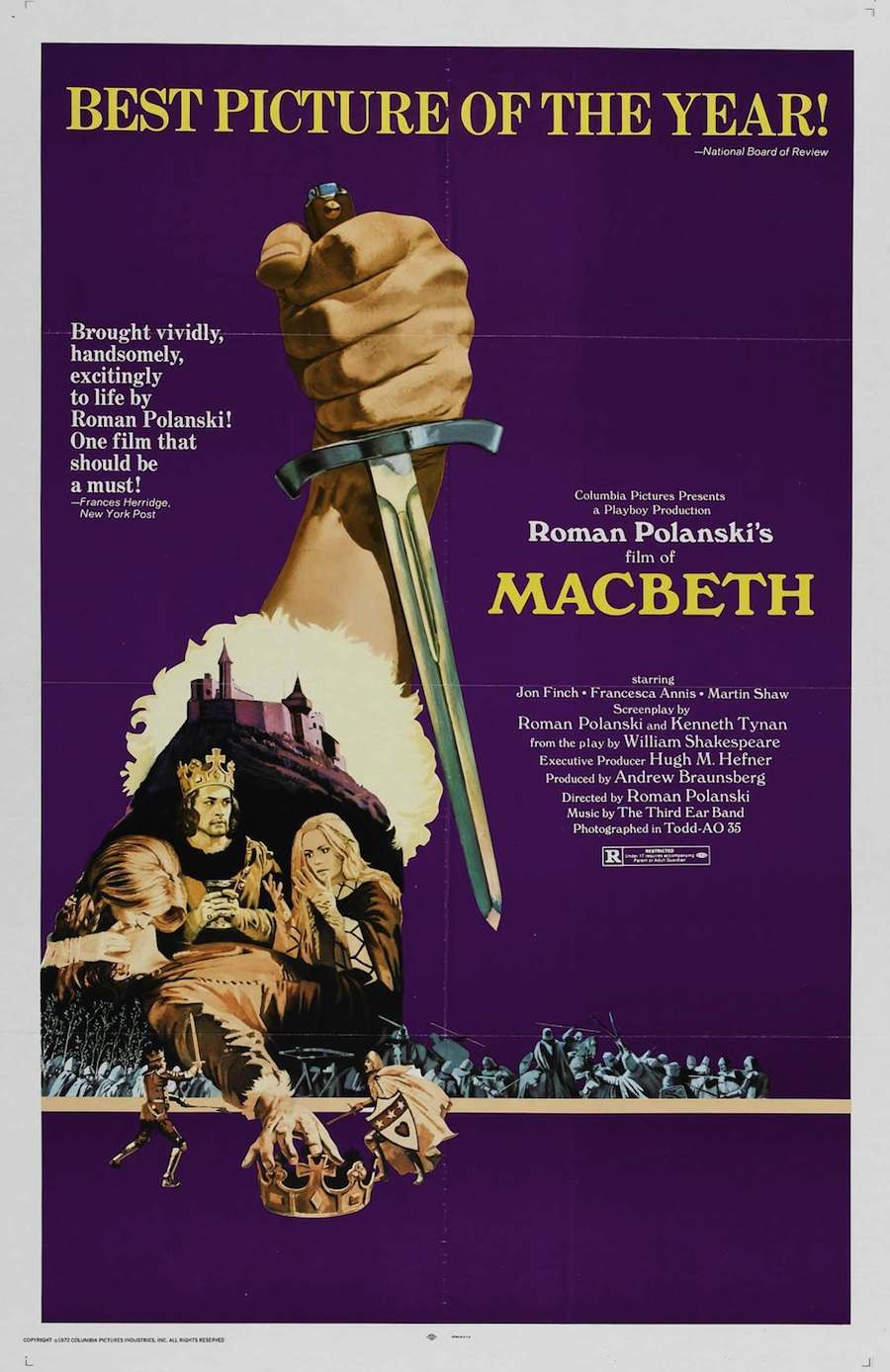

There was sex in this film. Not much. Just enough to give a little frisson. Hef liked it. It would be a calling card to maybe making more films and maybe more money. Maybe another Playboy Club in England? Everyone would think of him differently now he had made a serious film. A film of Shakespeare’s MacBeth.

Polanski hadn’t known what to do after Sharon was killed. Everything was futile. Everything was pointless. He couldn’t think of a subject that he could dignify with a year of his life. He watched Hef watch the girls by the pool. Who would have thought Hef would have helped him? He wondered what Hef was thinking about. The press call was in ten minutes. They had flown to France in a plane with a Playboy bunny on its tail fin.

Polanski was thinking about what he would say. Something about how he couldn’t work after what happened. I couldn’t think of a subject that seemed worthwhile or dignified enough to spend a year or more on it, in view of what happened to me. Did that sound pompous? Maybe, maybe. I couldn’t make another suspense story. And I certainly couldn’t make a comedy: I couldn’t make a casual film. That’s why he had chosen Shakespeare. That’s why he had chosen The Tragedy of MacBeth. It’s a tragedy because MacBeth chose what he wanted to do—-he didn’t have to kill the King. He didn’t have to kill anyone to get power. But when he did, he was undone.

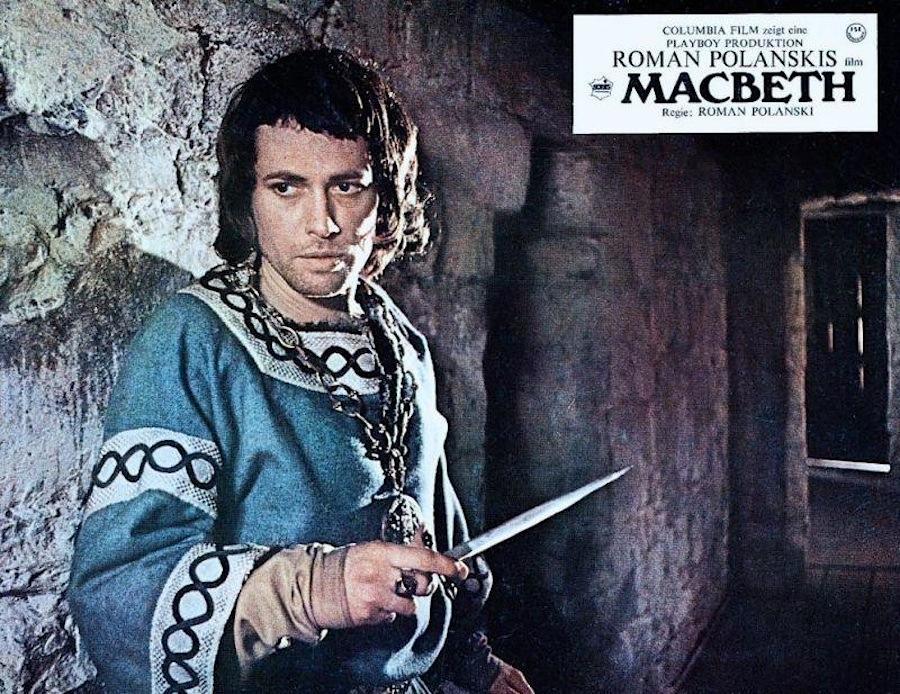

Polanski wanted make a film that reflected something about what was going on now. The violence, the sex, the energy. He said to Kenneth Tynan—-We don’t want no middle aged people in this. No Olivier. No Gielgud. No whoever. Young. Unknown. He’d met Jon Finch on a flight. Sat next to him. Listened to his stories. He was so full of life, so magnetic. He cast him without a thought. Jon is Macbeth. There was that moment when some of the cast thought Who the fuck is this? Some TV actor? Fuck them. Then they saw him act. He was good. He very very very good. And he looked good on camera.

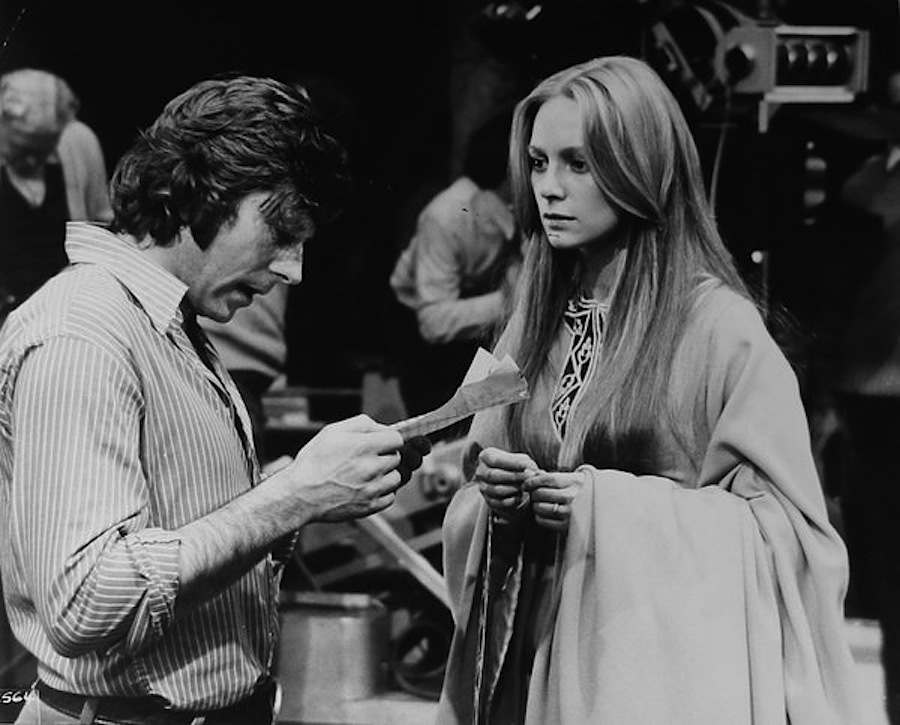

They were all good. Francesca Annis. She was good. Lady MacBeth. She had worked with Elizabeth Taylor. Been taken under her wing. She was going to be the next Elizabeth Taylor. She was better than Elizabeth Taylor. Ken said he’d seen her during filming in a drab scene. Then he said, You filmed a take and she was electric, electric. I told him I popped amyl-nitrite under her nose. The press will be here soon.

The press came. They watched previews. The critic Pauline Kael claimed the excessive violence in the movie was Polanski’s response to his wife’s murder. It was a trivialising thing to say. It got Kael attention—-and that’s what she really liked. The critics thought the casting strange. Why cast unknowns? Derek Malcolm in the Guardian said they were adequate—-damning with feint praise. The main problem was understanding why Polanski had made the film in the first place and why he had made it with Hugh Hefner? Some journalists had crude but wrong suggestions to that. But none of them looked at the film as a piece of work on its own—-as an intelligent, well crafted, beautiful movie that examined issues of ambition, guilt, and abdication of responsibility. The film bombed. It became a movie to be screened on weekday afternoons for school kids studying MacBeth—which was a real tragedy. Hefner held off on producing any more big movies unless they could make money. Polanski went back to Hollywood and made Chinatown.

As the writer G. K. Chesterton noted:

…the whole point about Macbeth [is] that he knows what he is doing. It is not a tragedy of Fate but a tragedy of Freewill. He is tempted by a devil, but he is not driven by a destiny. If the actor pronounces the words properly, the whole audience ought to feel that the story may yet have an entirely new ending, when Macbeth says suddenly, “We will proceed no further in this business.” The incredible confusion of modern thought is always suggesting that any indication that men have been influenced is an indication that they have been forced. All men are always being influenced; for every incident is an influence. The question is, which incident shall we allow to be most influential. Macbeth was influenced; but he consented to be influenced.

Francesca Annis as Lady Macbeth.

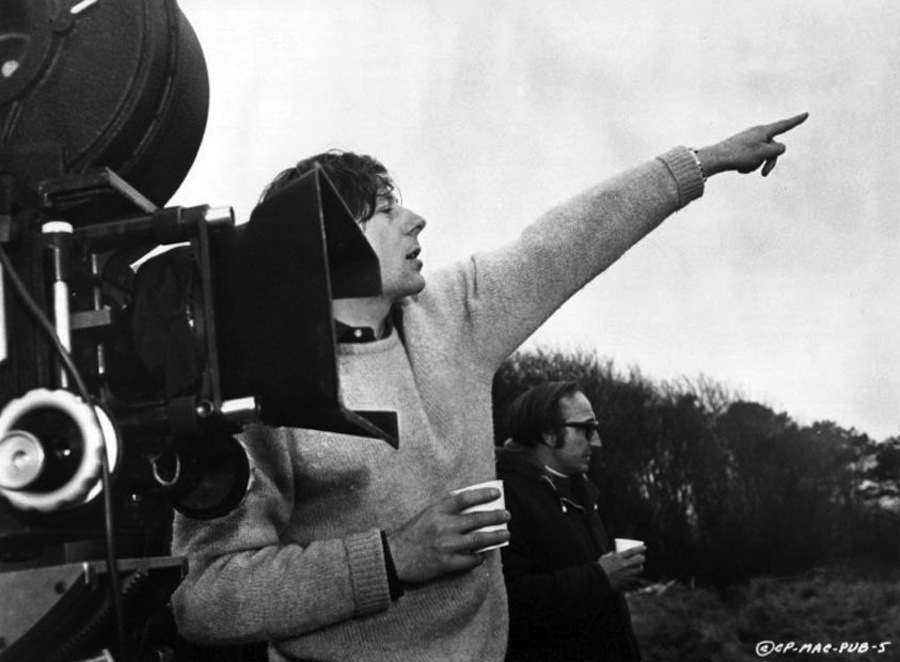

The film’s producer Hugh Hefner with Roman Polanski at a press conference.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.