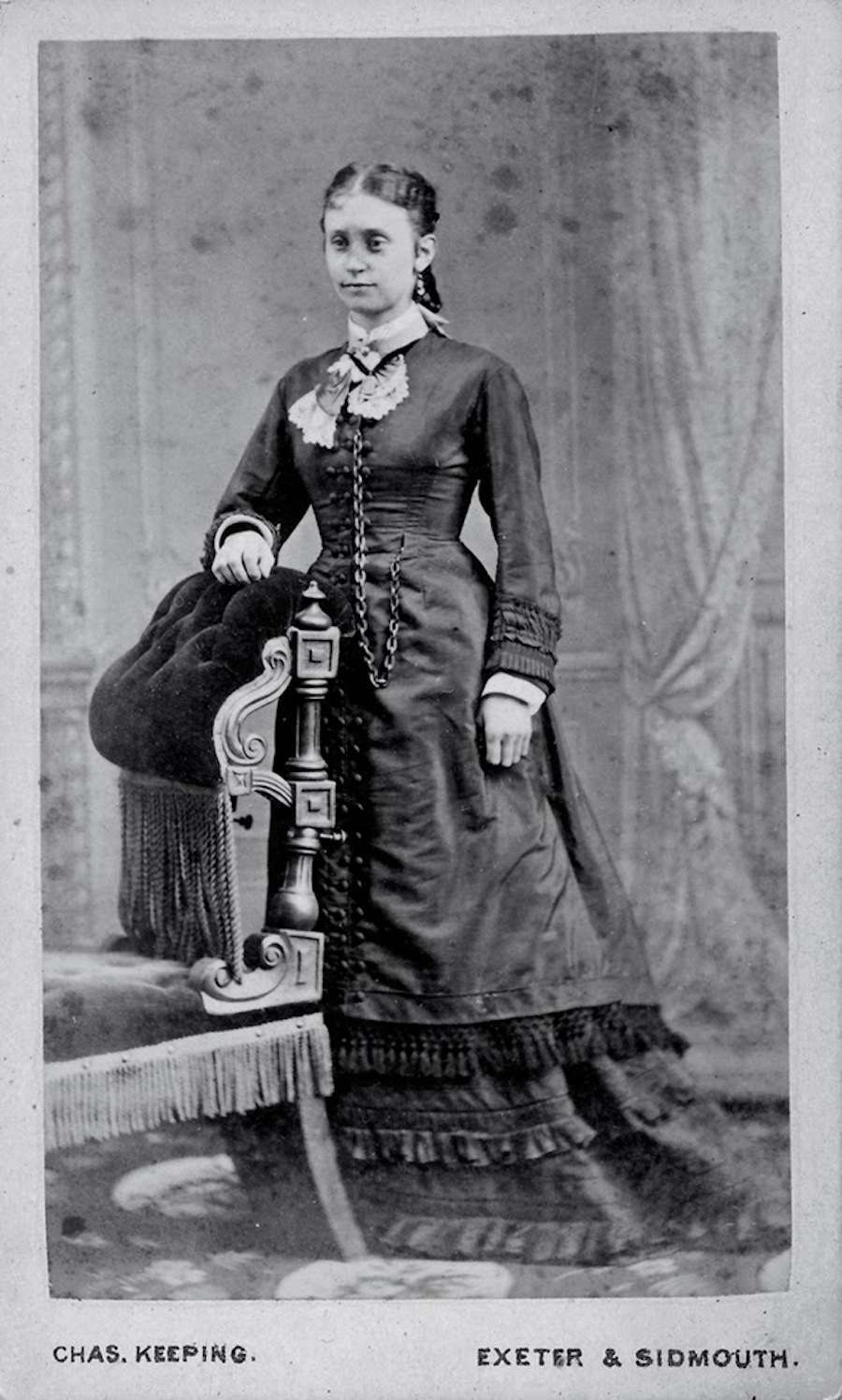

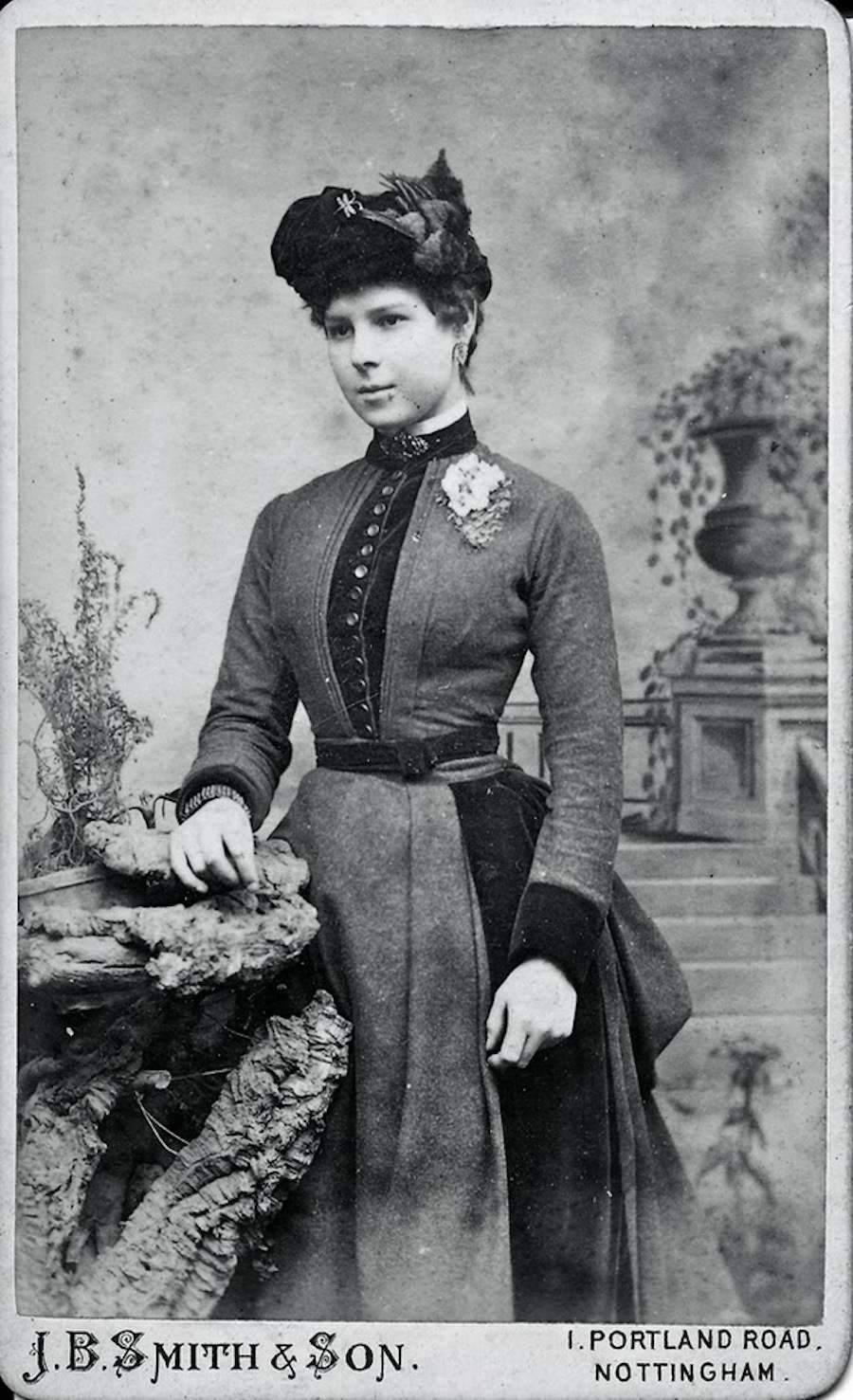

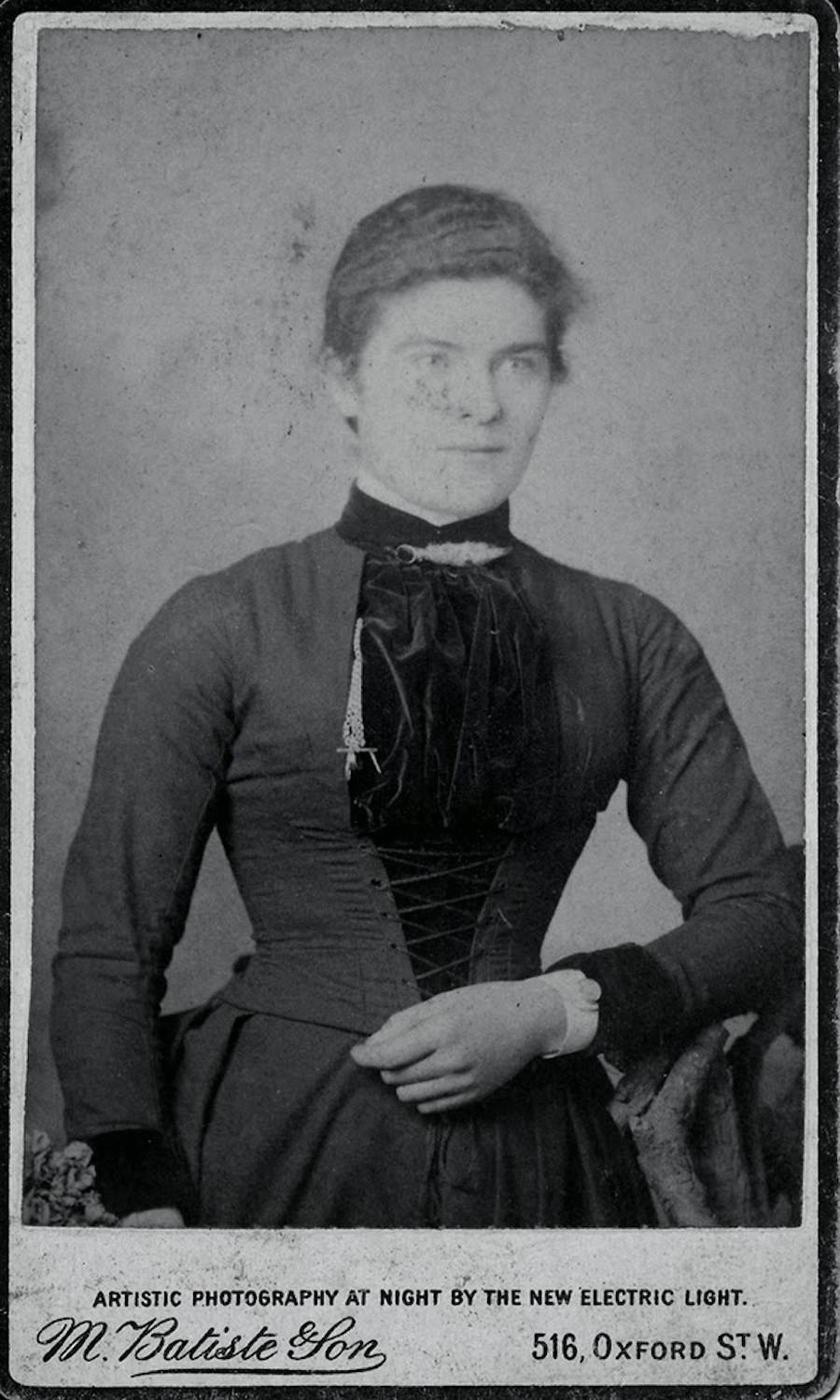

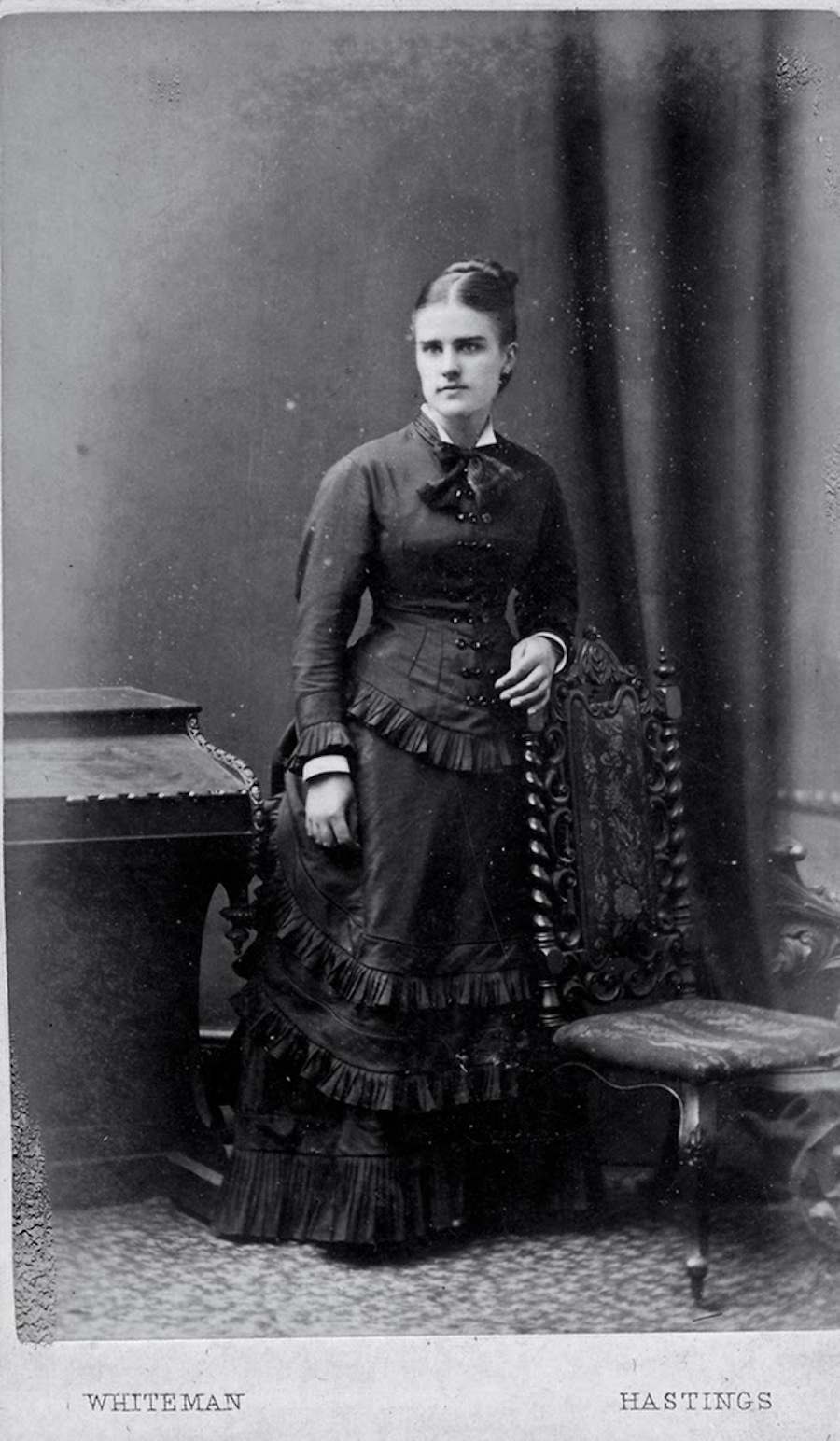

Here then are the very real governesses, Miss Havershams, lovers, mothers and heroines of Victorian fiction–upright, firm, steadfast and loyal–or so it would seem. But look closely and you will see a sadness in their eyes, a longing that suggests the loss of a life that might have been lived instead of the one they were constrained to endure. Victorian women had no rights, no power, no real freedom, no means to own property or have money–for if they married everything they possessed was given over to their husbands.

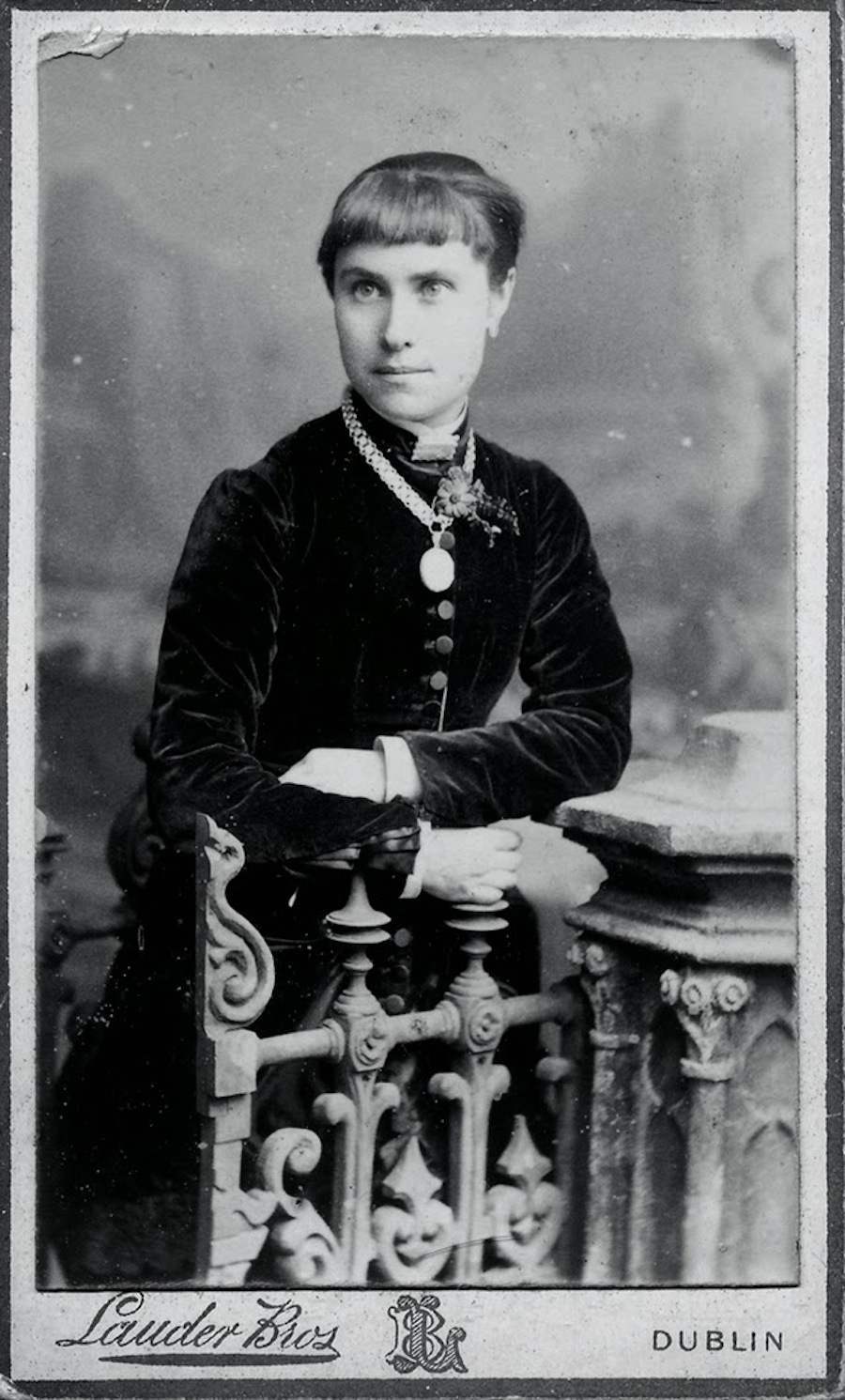

Unlike their working class counterparts, these women did have some opportunity–even if it was opportunity dictated by the needs of men. Having a photograph taken was about class and position, and reinforcing the expected roles. But in the same way some upper class women had tattoos hidden on parts of their skin–to reclaim a small part of their bodies–having a photographic portrait was also about establishing a form of independence away from the identity imposed by others on so many of these women.

Photographs from this era can be dated by poses and backdrops:

1860s

Early 1860s most photographers’ studios offered plain backgrounds, with possibly a column for the sitter to lean on, and a velvet drape on one side.

Men and women were usually photographed at full length, standing, or occasionally seated.

Later 1860s more elaborate painted backcloths were introduced, depicting windows, archways, bookcases and other heavy, imposing-looking furniture, and balustrades.

1870s

The painted backcloths became more fanciful, with outdoor, parkland scenes, with fences and stiles. Fences as studio props were introduced, against which the sitter posed. Heavily padded, fringed and tasseled furniture features largely in studios, for the sitter to lean against or sit upon. Half-lengths and seated poses are more common.

1880s

The painted backcloths become more dramatic, and the props more elaborate and evident. The “outdoor” fiction of the backcloth is now brought into the foreground, with ivy covered tree stumps and rocks for the sitter to sit on, clumps of grass and pebbles on the floor.

1890s

Studio settings now rely more on props and furniture to set the scene, rather than painted backdrops. Typical props are oriental screens, mirrors on stands, potted palms, and bamboo furniture of all kinds, the studio aiming to look like a high-class conservatory.

The fashion for “close-up” portraits of the head and shoulders only, possible with the improved lenses of the 1890s, meant that the background was becoming less important. “Vignette” photographs are typical of the 1890s, in which the head forms an oval which fades into a pale blank background.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.