The romanticizing of the Mafia in American culture, and “American cinema in particular,” writes A.O. Scott in a review of 2006 Italian documentary Excellent Cadavers, is not likely to abate any time soon. “The colorful idioms of wiseguys have helped many a big-city newspaper columnist through a slow day, and the characteristic Cosa Nostra mix of Old World ethnic sentimentality and cutthroat capitalism has proved irresistible to artists of the big and small screens.”

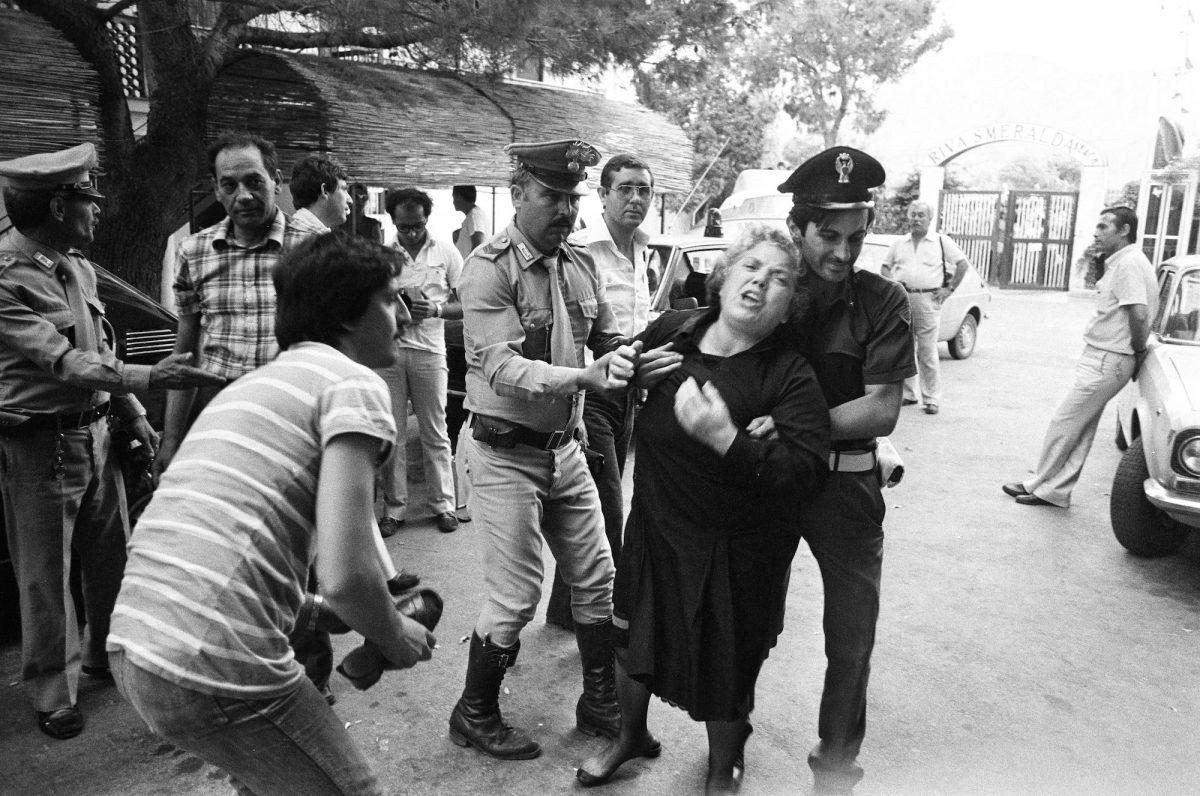

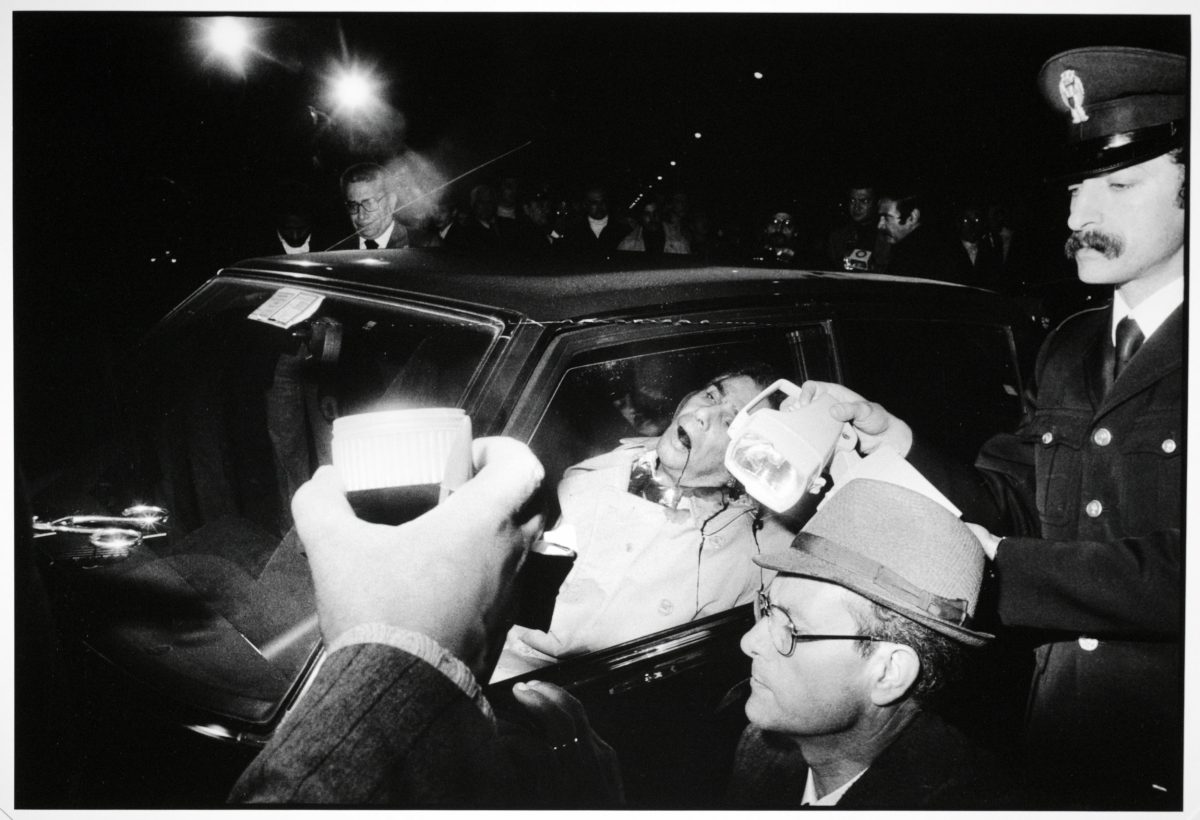

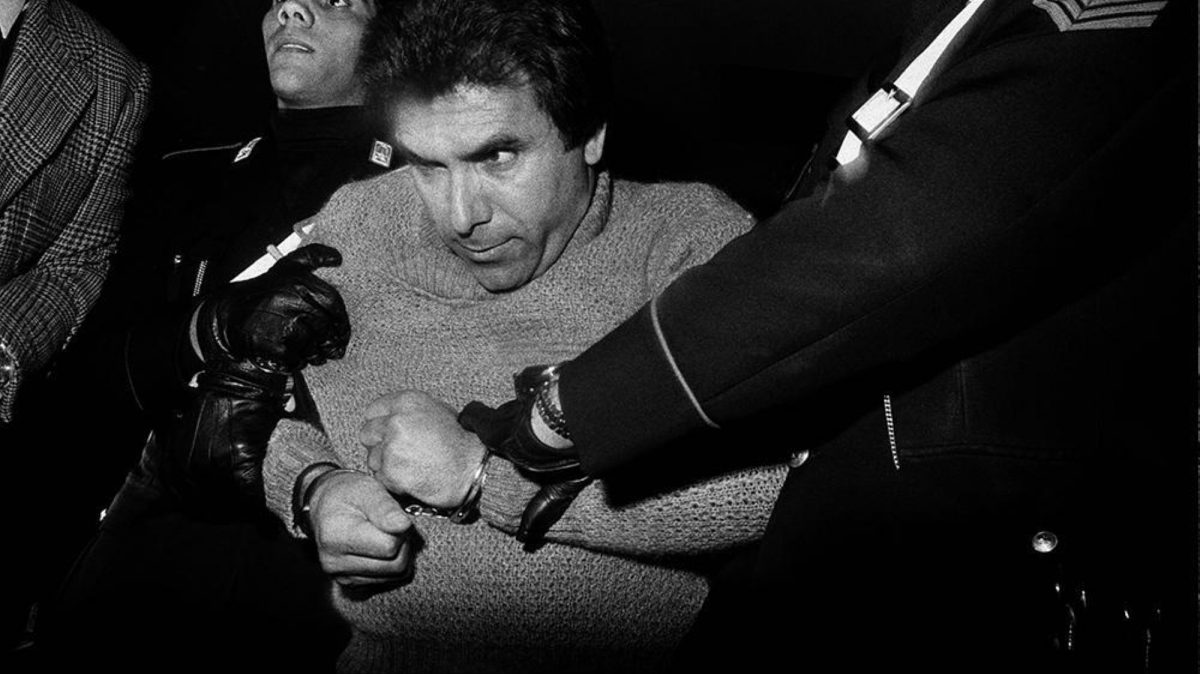

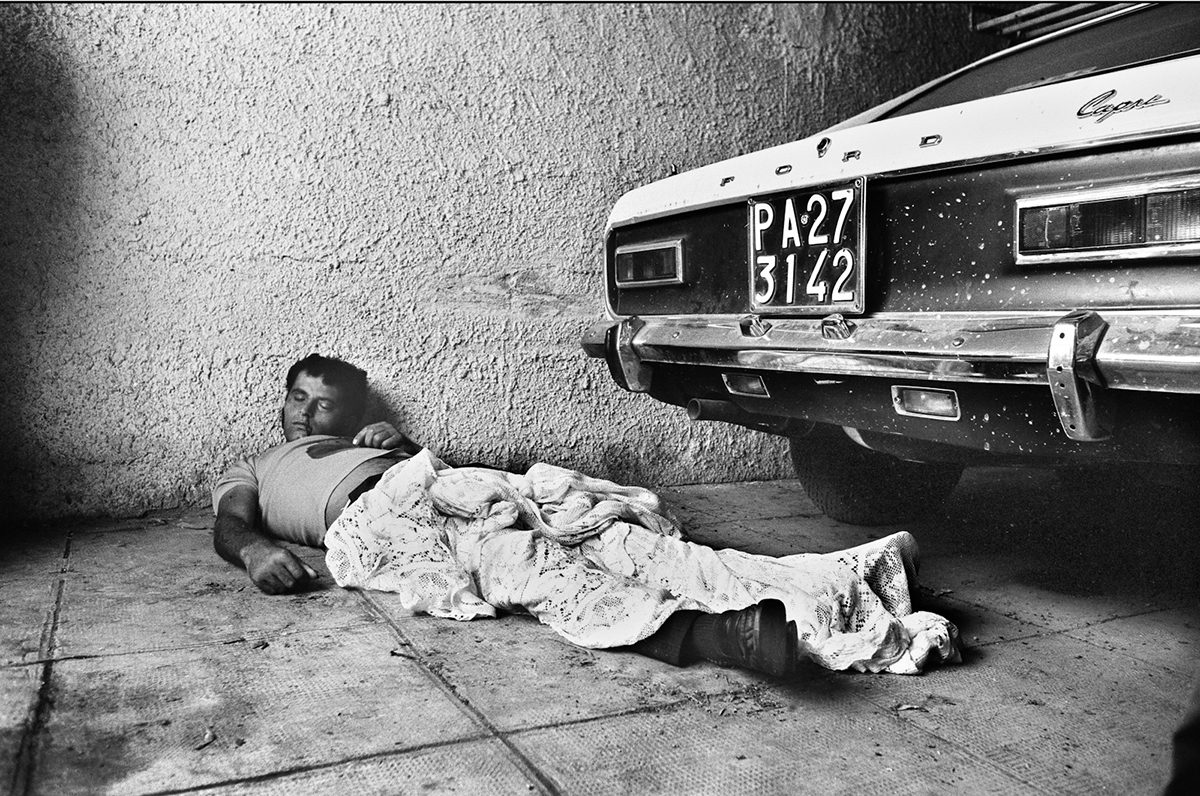

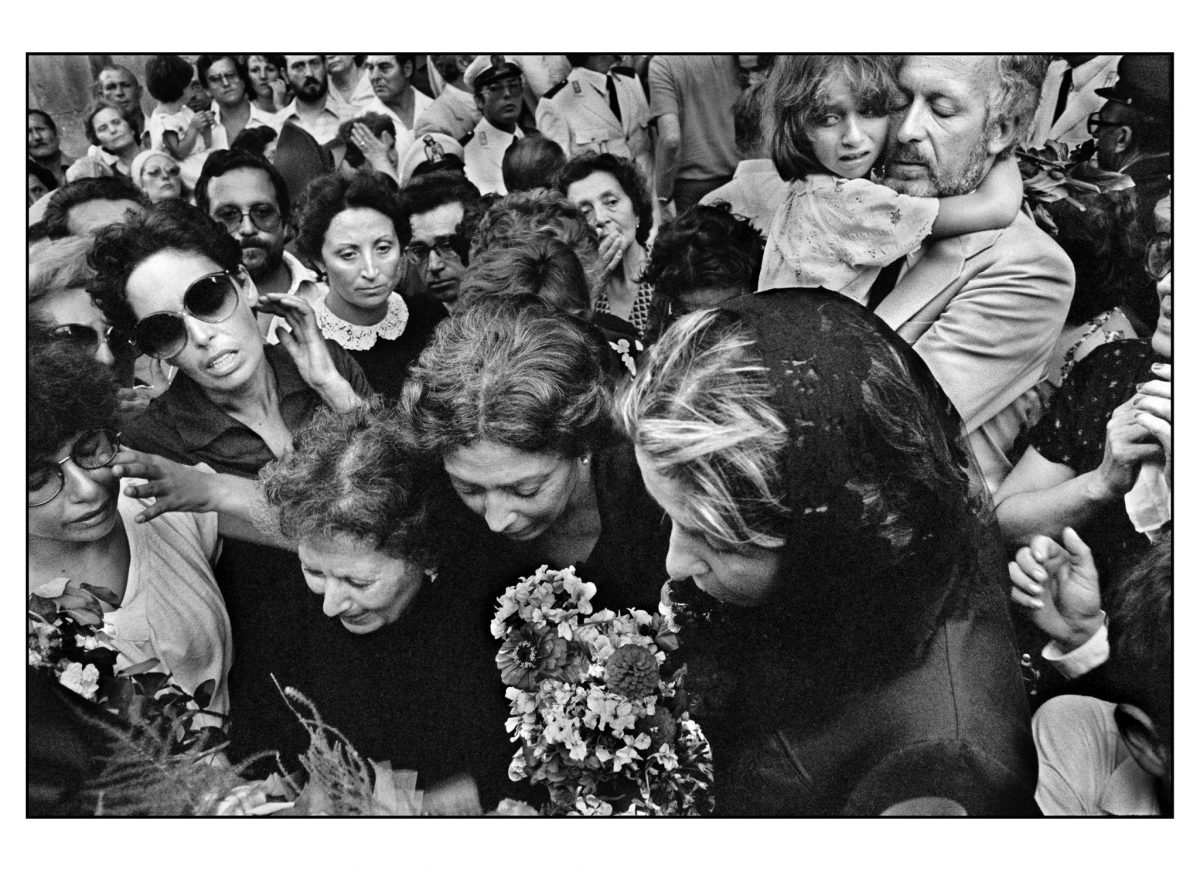

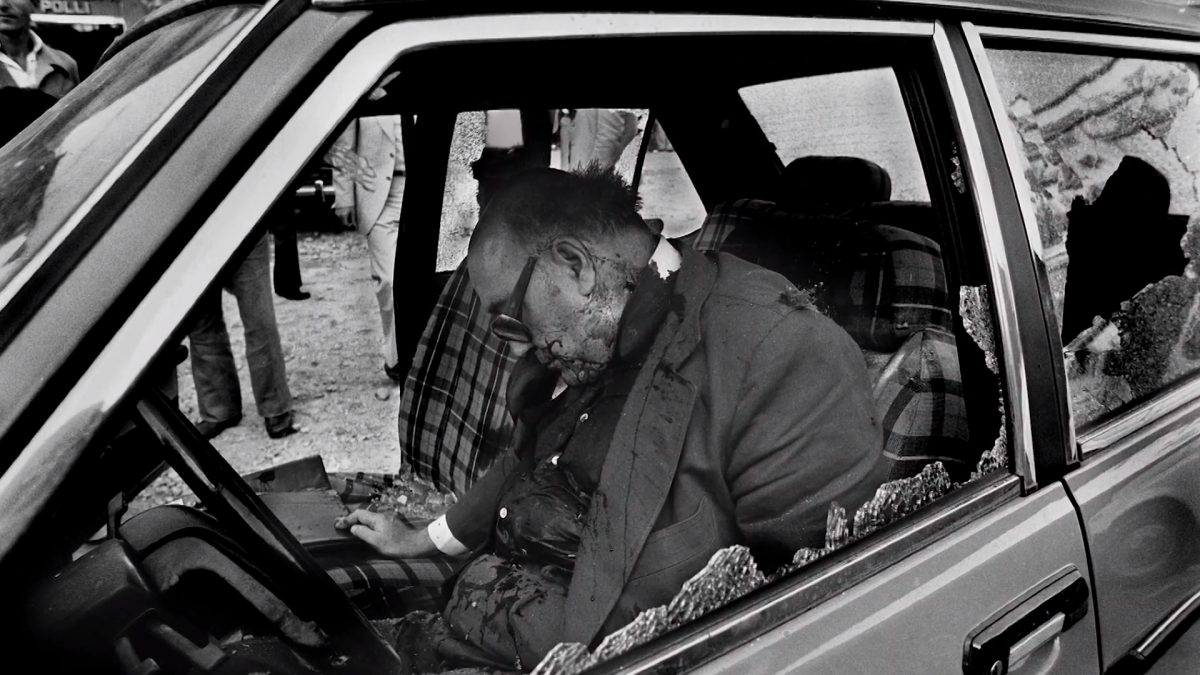

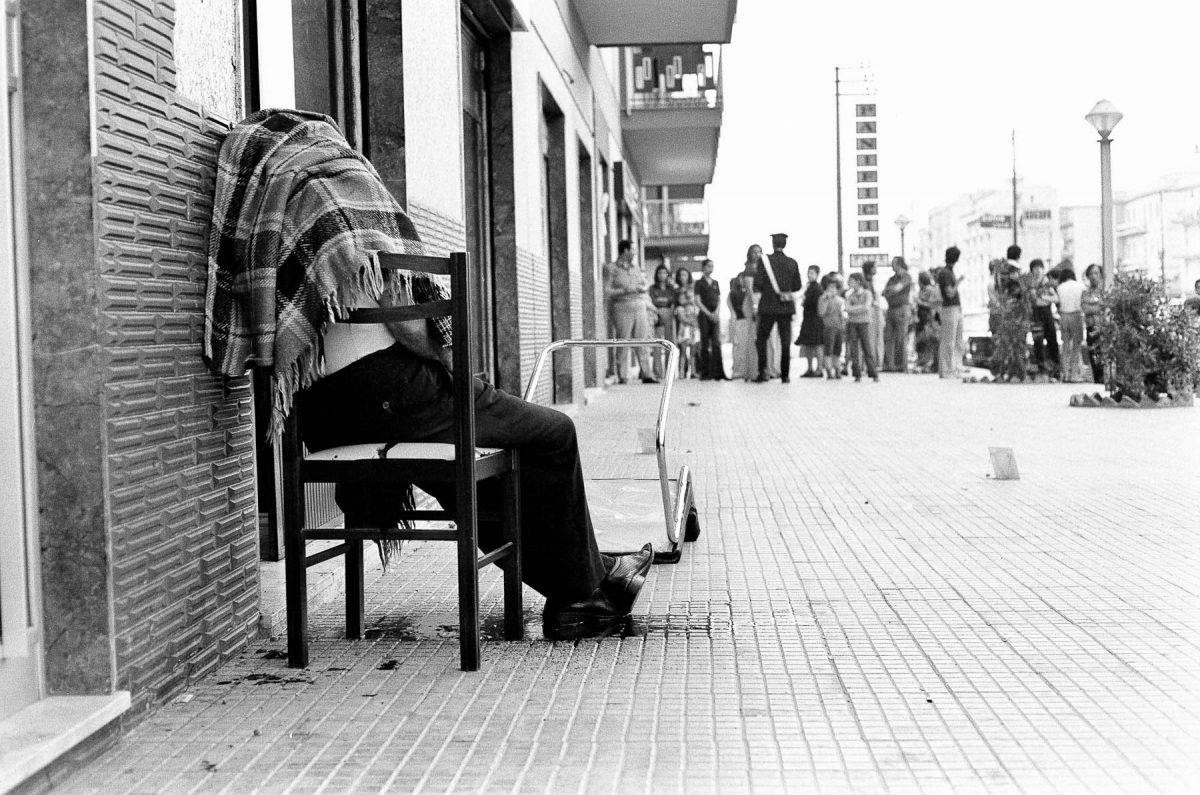

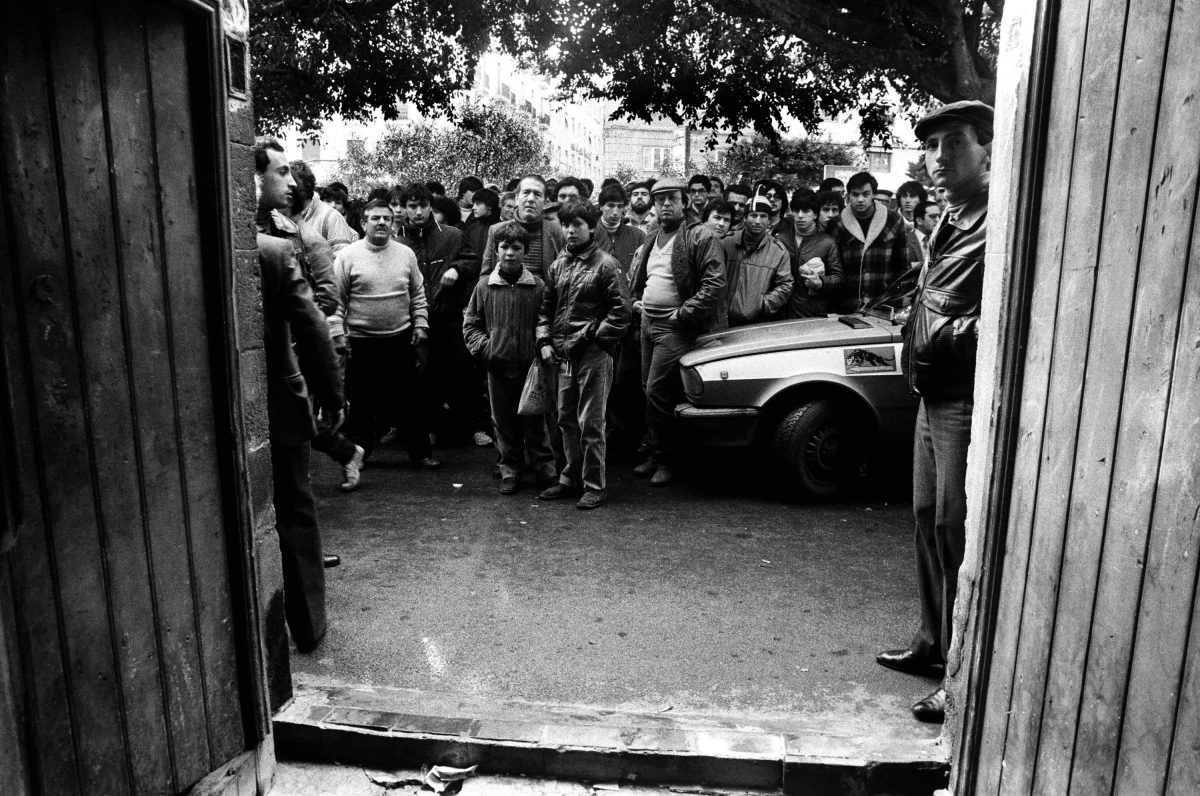

Excellent Cadavers “offers an implicit critique of the lovable-goombah view of organized crime” and features frequent appearances from photographer Letizia Battaglia, who captured Mafia crime and its aftermath in Sicily throughout the last decades of the 20th century. Battaglia risked her life to tell these grim stories of violence and corruption, considering it her duty to show the brutal truth. In a 2001 interview, she described her philosophy:

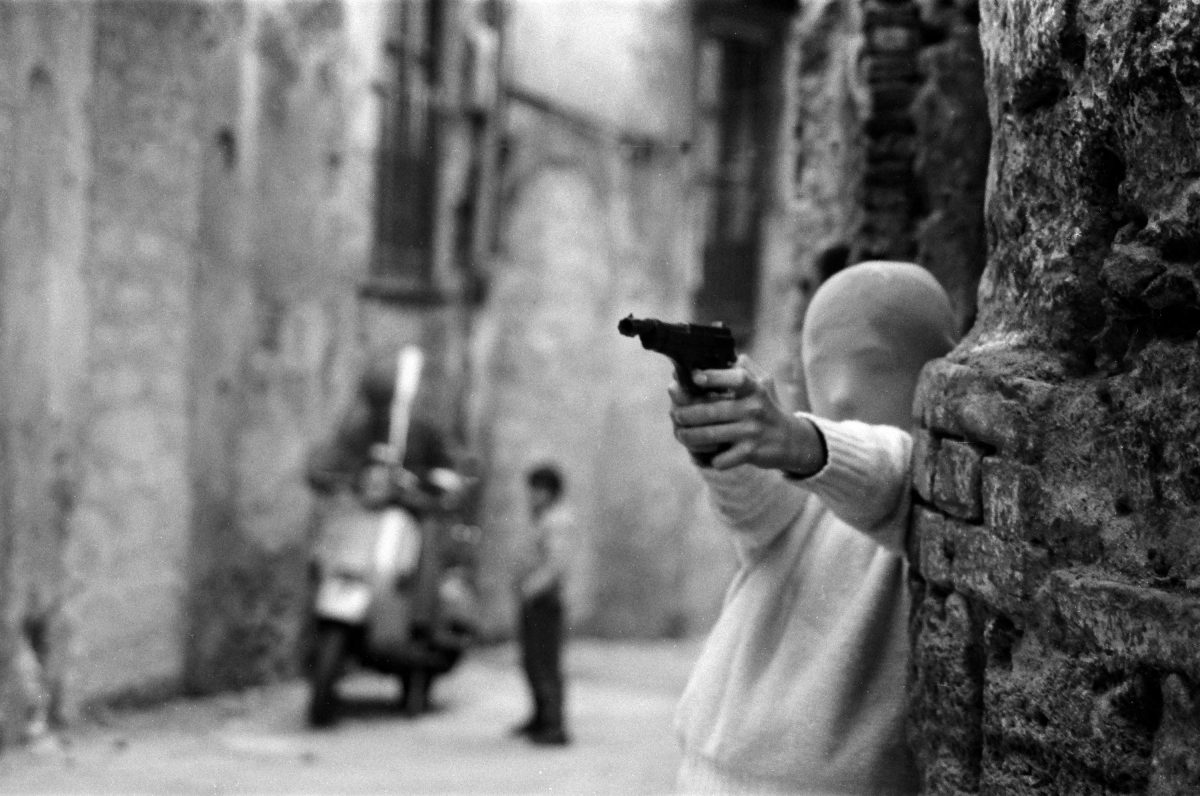

Let’s say that you work for a newspaper – be it La Repubblica, Il Corriere della Sera, or Il Manifesto, or L’Ora. The editor of the newspaper sends you on the scene of a crime by giving strict orders: “Go to photograph what happened”. You go, you arrive on the site, you immediately get nausea (I remember, as far as I’m concerned, that the smell of blood has not abandoned me ever since the first time I found it in front of me), you find a poor human being tortured, humiliated, violence cut short his life and, nevertheless, you have to photograph it. Why should you? Because this is not just about the dead in question! You as a photographer should photograph this and more, you should photograph the poverty, the pain, the rich and the poor and to tell all this to the world. The world must know the reality. Of course, the person in question, the dead cannot defend themselves from your lens! This is true. But it is true that this image, the image of a mangled corpse, maybe it will tell of a time when men were barbarians, one story among many that will serve history.

This past year, Battaglia became the subject of her own documentary, Shooting the Mafia, directed by Kim Longinotto, “a rollicking depiction of the wonderfully self-possessed” photographer and her eventful life. Battaglia married at 16 to escape her repressive Catholic family, raised three daughters, then suffered a nervous breakdown and filed for divorce in 1971. Not long after, she took up photojournalism and, in 1974 became the first Italian woman photographer employed at a daily newspaper, L’Ora.

Then as now, photographers faced thorny ethical questions about how to document violent crime. Battaglia received death threats, “her camera was smashed,” notes Miss Rosen at Huck Magazine. “But the mafia let her live.” This is, in part, because her photos of murder scenes served as a sinister form of free publicity. “Letizia’s photos were always on the front page of the newspaper and kept the killings in the minds of the people,” says Longinotto. “They are making the community look at what is happening. They are powerful threats against speaking out.”

Battaglia served as the L’Ora’s photo editor until the paper shut down in 1990. She worked “on the front-line as a photo-reporter,” notes the Open Eye Gallery, “during one of the most tragic periods in contemporary Italian history, the so-called anni di piombo—the years of (flying) lead, as they say in Italian”—eighteen years during which the Corleonesi family murdered politicians, policemen, members of rival families, and anti-mafia judges, including two of Battaglia’s friends, Giovani Falcone and Paolo Borsellino.

Despite the danger and the personal loss, Battaglia continued her fight, both behind the camera and away from it as an editor, publisher, activist, and politician, holding a seat on the Palermo city council from 1985 to 1991. After 20 years of documenting the Mafia, she stopped taking photographs in the mid-nineties. “One of her last photos shows a young boy who was shot in the back of his head after seeing his father murdered,” writes Rosen. “It was never the same,” Battaglia says in the documentary about her life. “You can never be happy after that kind of horror.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.