We look at life though a human eye. What an animal sees is largely a mystery to humans. Do we have any idea what it’s like to be a bat or think like a spider?

Humans will look for familiar traits in animals. We will select creatures that reflect us, beings that French anthropologist Claude Levi-Straus termed “good to think” (bonnes à penser). We will see in bears and lions lessons for ourselves. But look deep at the animals and might see something else.

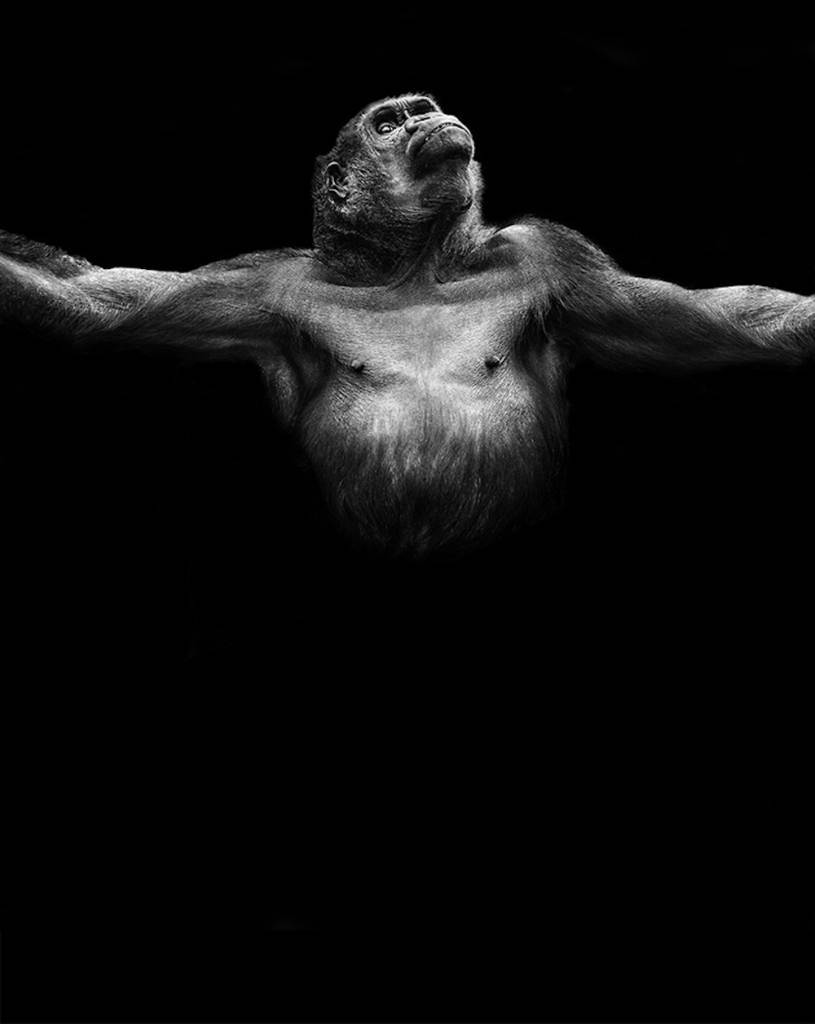

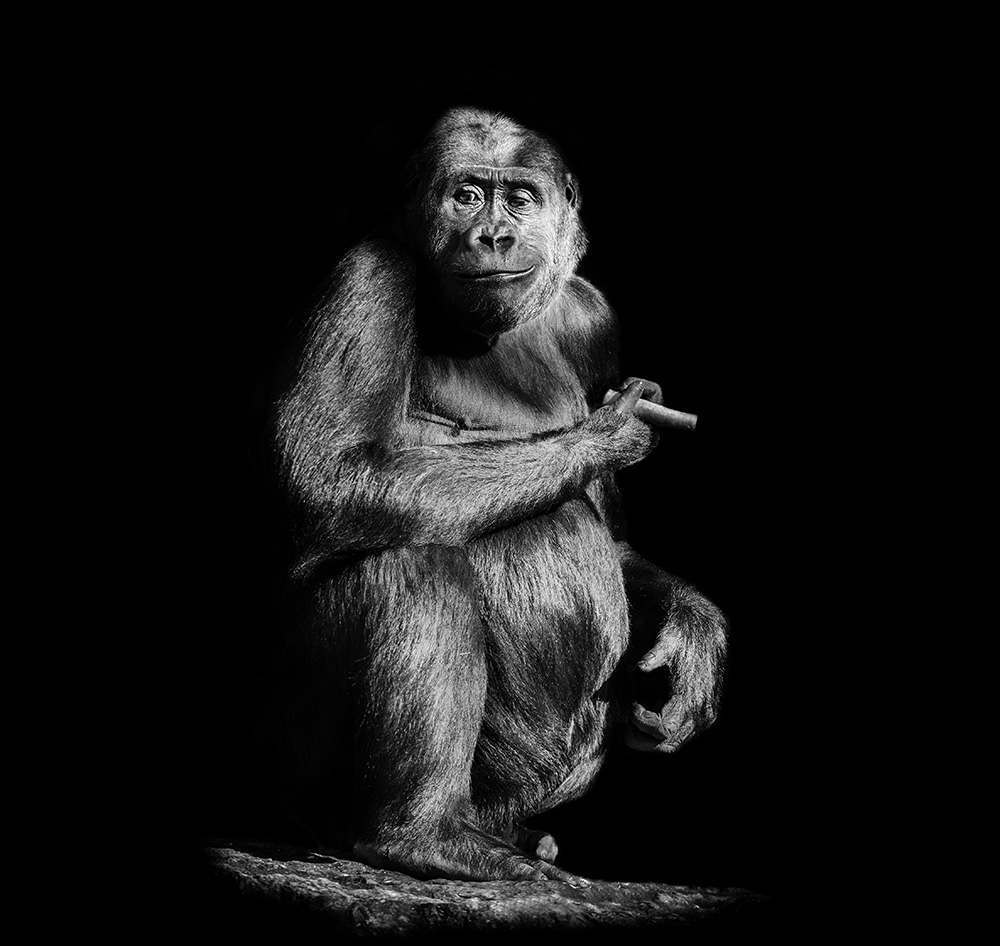

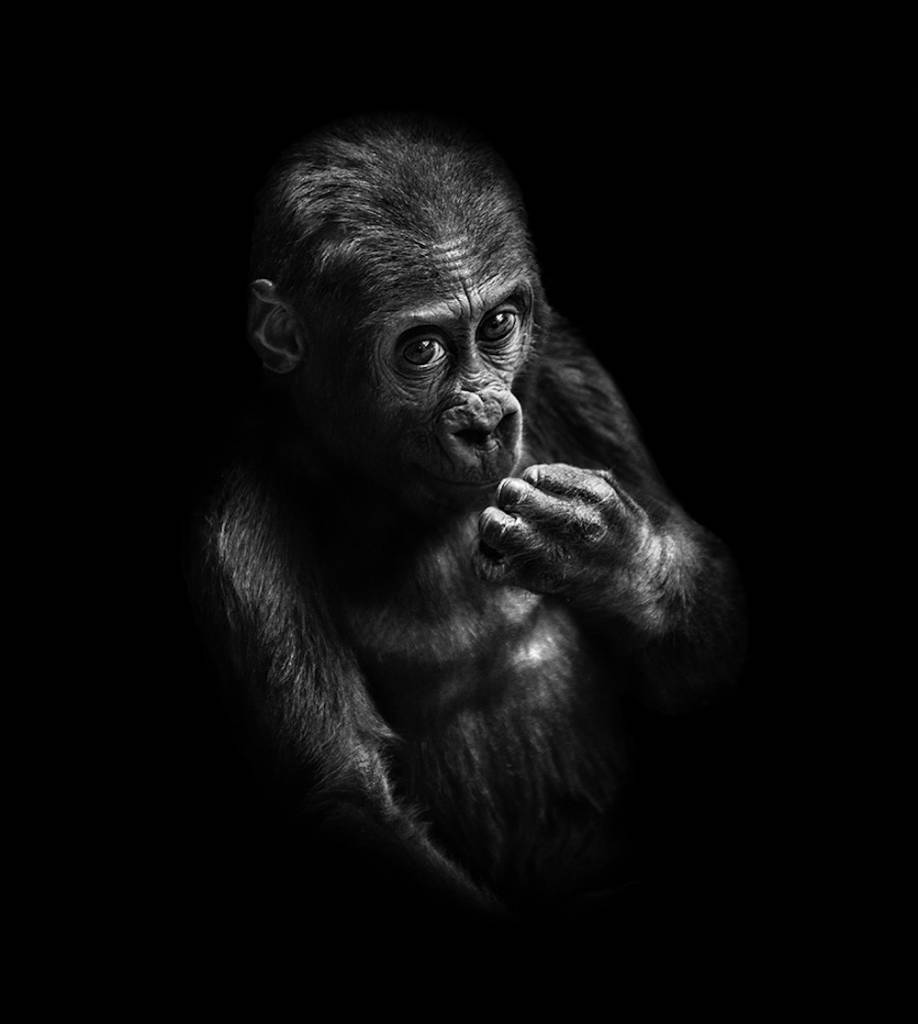

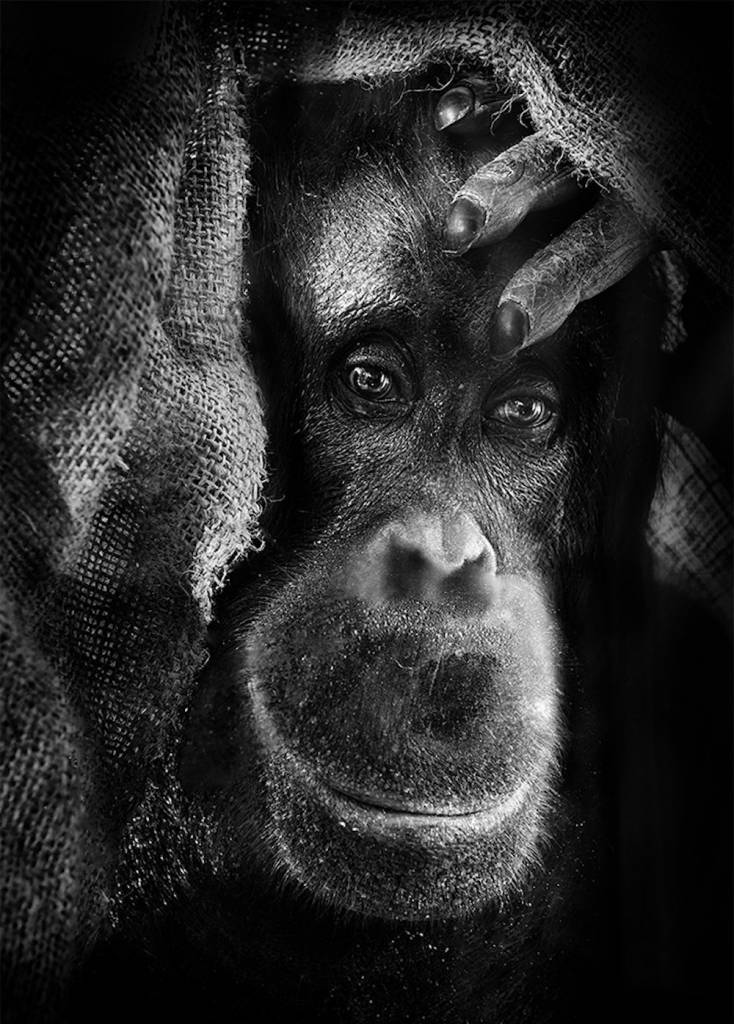

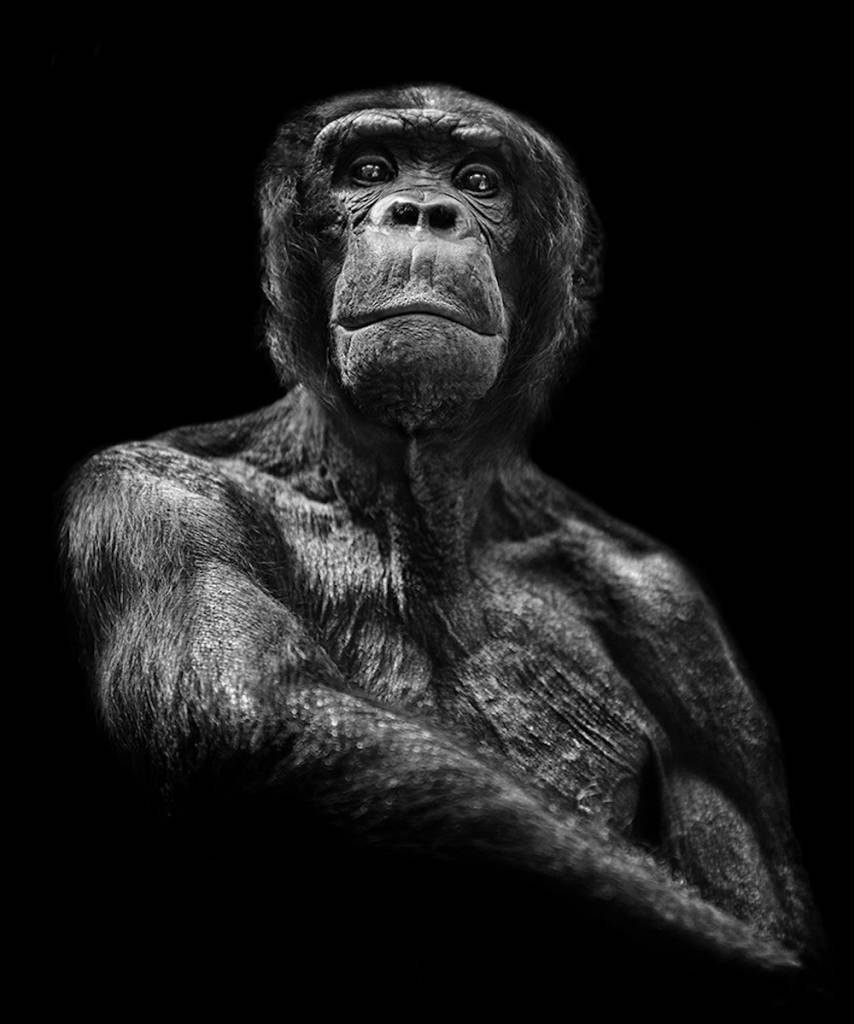

Paweł Bogumił’s series of photographs – inHUMAN: Portraits of Emotional Apes – blur the frontier between human and animal. He writes:

We strictly demarcate the world of humans and animals. Each creature except man we call an animal. Generally accepted boundaries are not not contractual but determined, and eliminates any space for beings between these two terms. We describe humans as living creatures, distinguished by the highest degree of development of the psyche and social life, while the rest are mere animals.

While visiting more than fifteen zoos in Europe, I observed and photographed living organisms which are the most similar to the human being, that is: apes. Initially I was looking for superficial, anatomical similarities and deceptively manlike behaviors… we should not treat them as mere animals, but maybe we should think of them as self aware non-human persons full of emotions, limited by beastly instinct’s and reactions patterns.

Jane Goodall learned much whilst studying the chimpanzees at Gombe Stream National Park. She sees a key difference between us and them:

Even if there was no God, even if human beings had no soul, it would still be true that evolution had created a remarkable animal — the human animal — during its millions of years of labor. So very like our closest biological relatives, the chimpanzees, yet so different. For our study of the chimpanzees had helped to pinpoint not only the similarities between them and us, but also those ways in which we are most different. Admittedly, we are not the only beings with personalities, reasoning powers, altruism, and emotions like joy and sorrow; nor are we the only beings capable of mental as well as physical suffering. But our intellect has grown mighty in complexity since the first true men branched off from the ape-man stock some two million years ago. And we, and only we, have developed a sophisticated spoken language. For the first time in evolution, a species evolved that was able to teach its young about objects and events not present, to pass on wisdom gleaned from the successes — and the mistakes — of the past, to make plans for the distant future, to discuss ideas so that they could grow, sometimes out of all recognition, through the combined wisdom of the group

Desmond Morris offers more food for thought.

How we thrive:

Viewed as a pattern of human feeding behavior, a trip to the supermarket is the remarkable endpoint of a long journey through evolutionary time, a journey that started in the primeval forest and at the checkout counter. To me, it’s a story of an arboreal ape, which became a ground-dwelling predator, which in turn became a credit card customer.

How we live:

Some people call the city a ‘concrete jungle’ — but jungles aren’t like that. Animals in jungles aren’t overcrowded. And overcrowding is the central problem of modern city life. If you want to look for crowded animals, you have to look in the zoo. And then it occurred to me: The city is not a concrete jungle — it’s a human zoo.

Explore more of Paweł Bogumił’s wonderful pictures on his website.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.