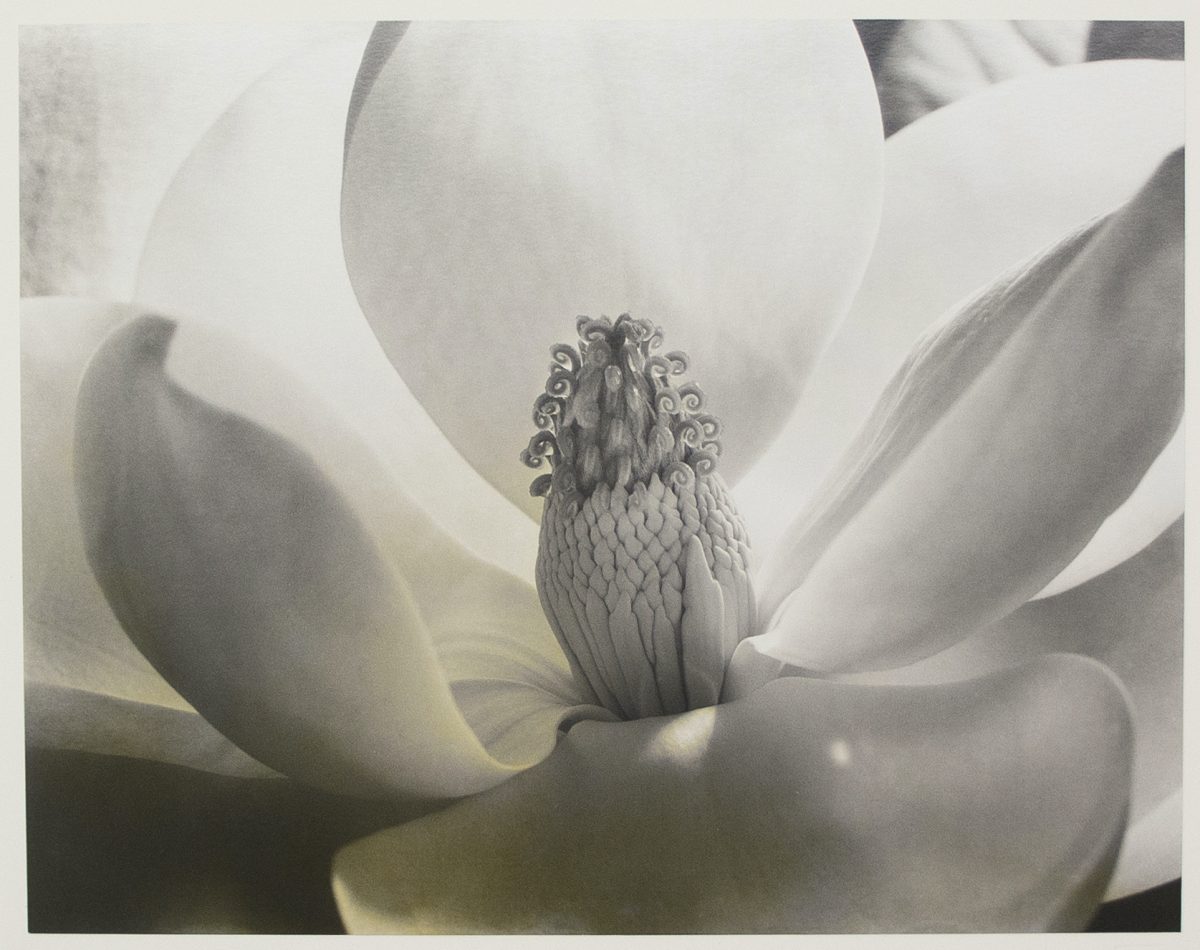

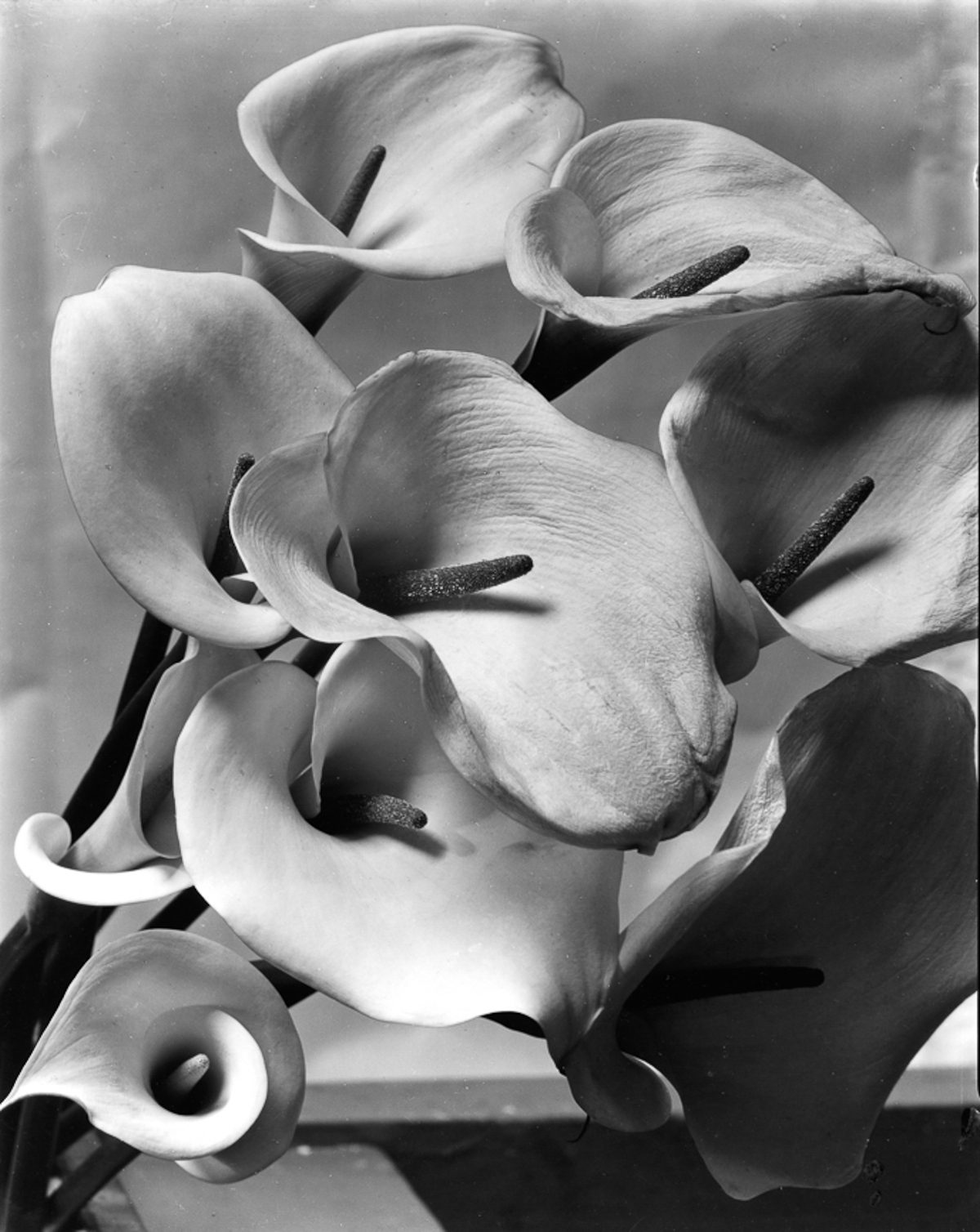

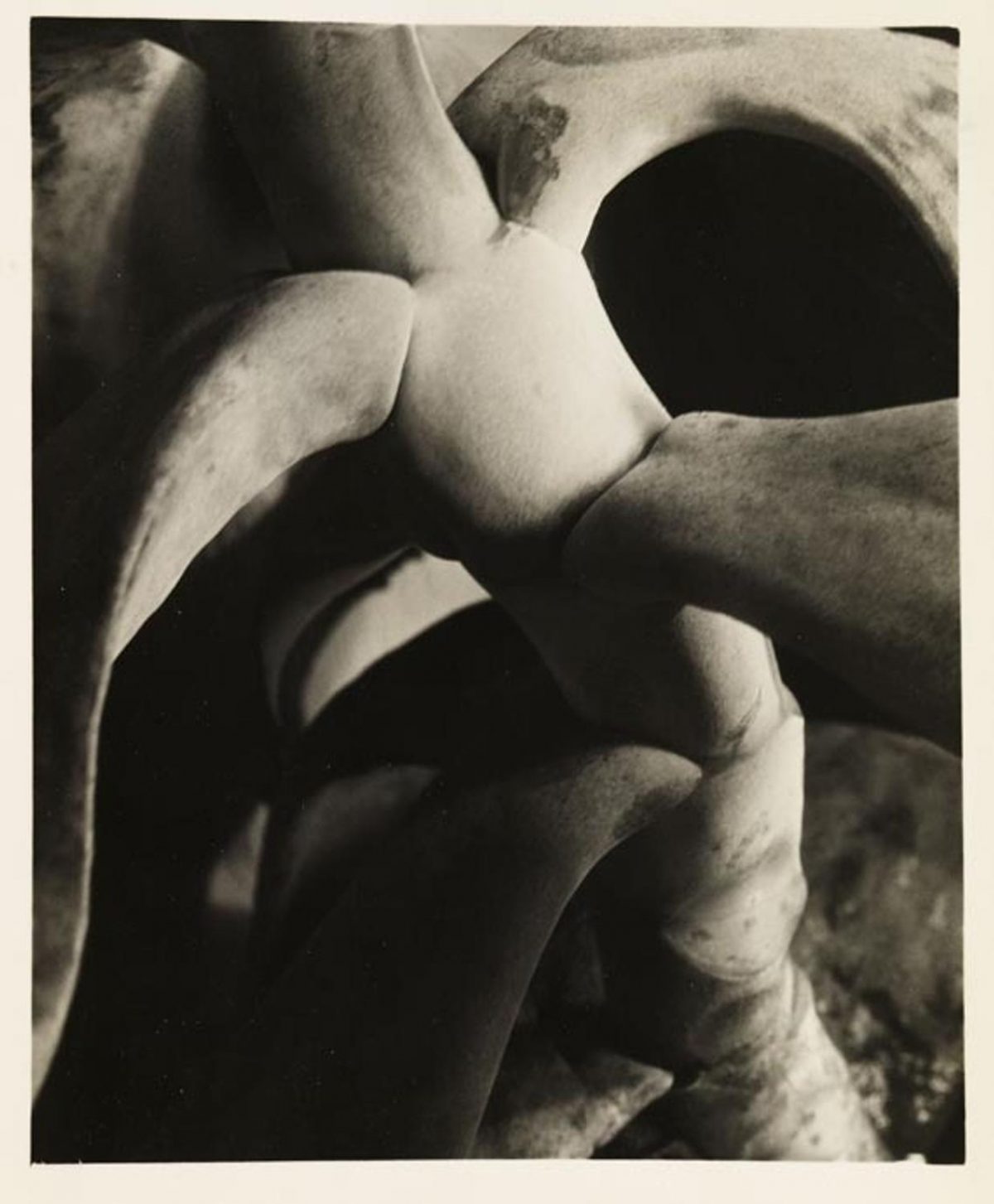

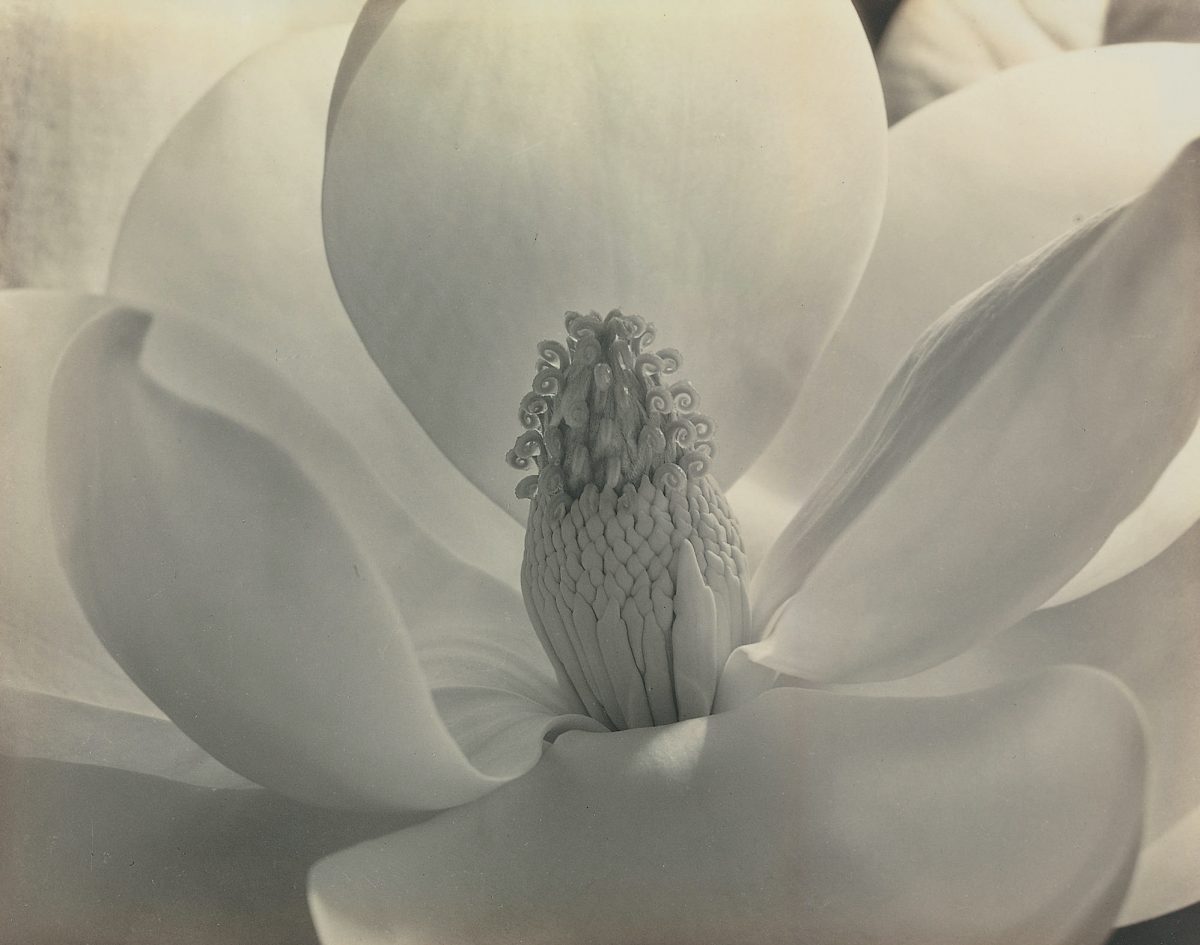

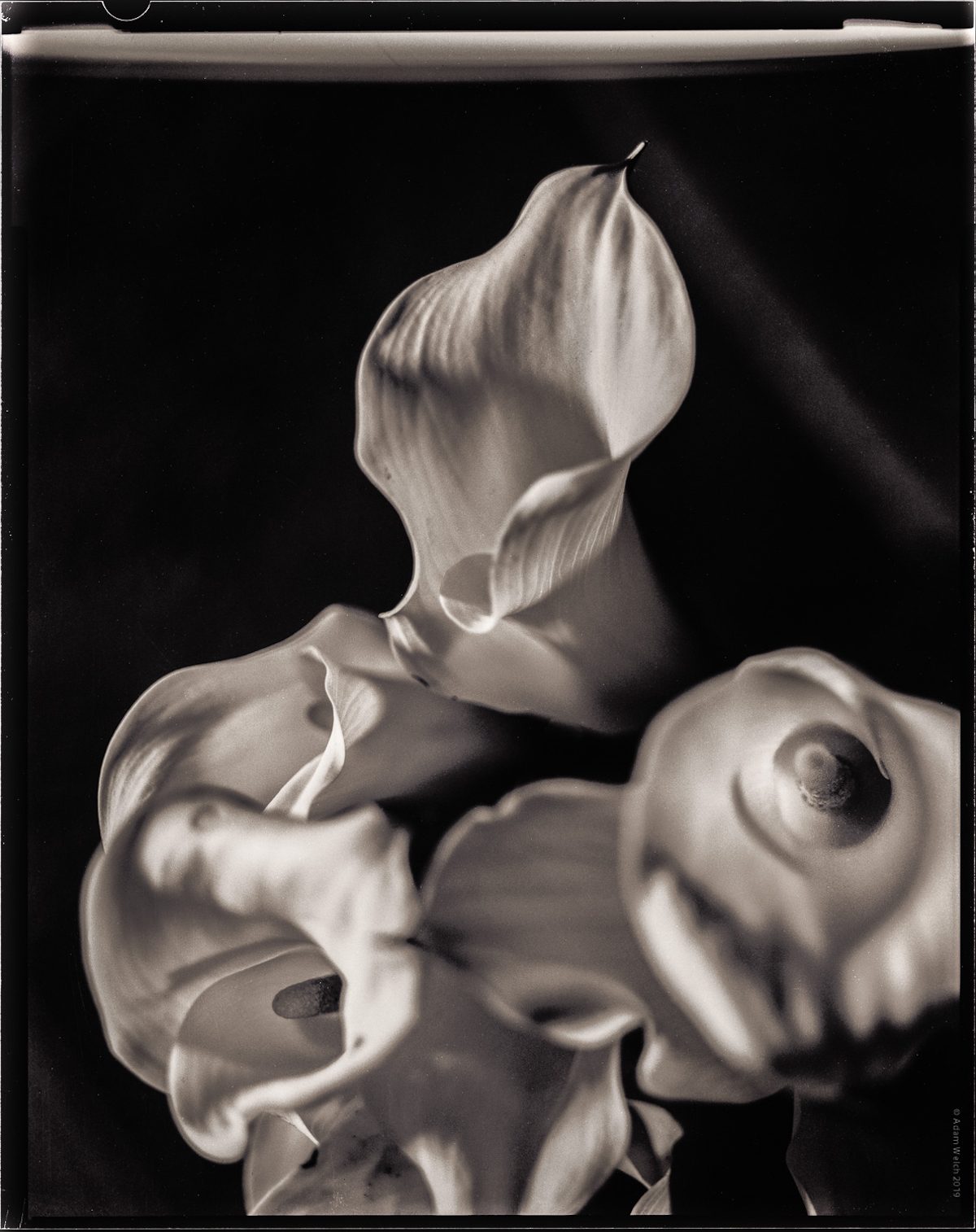

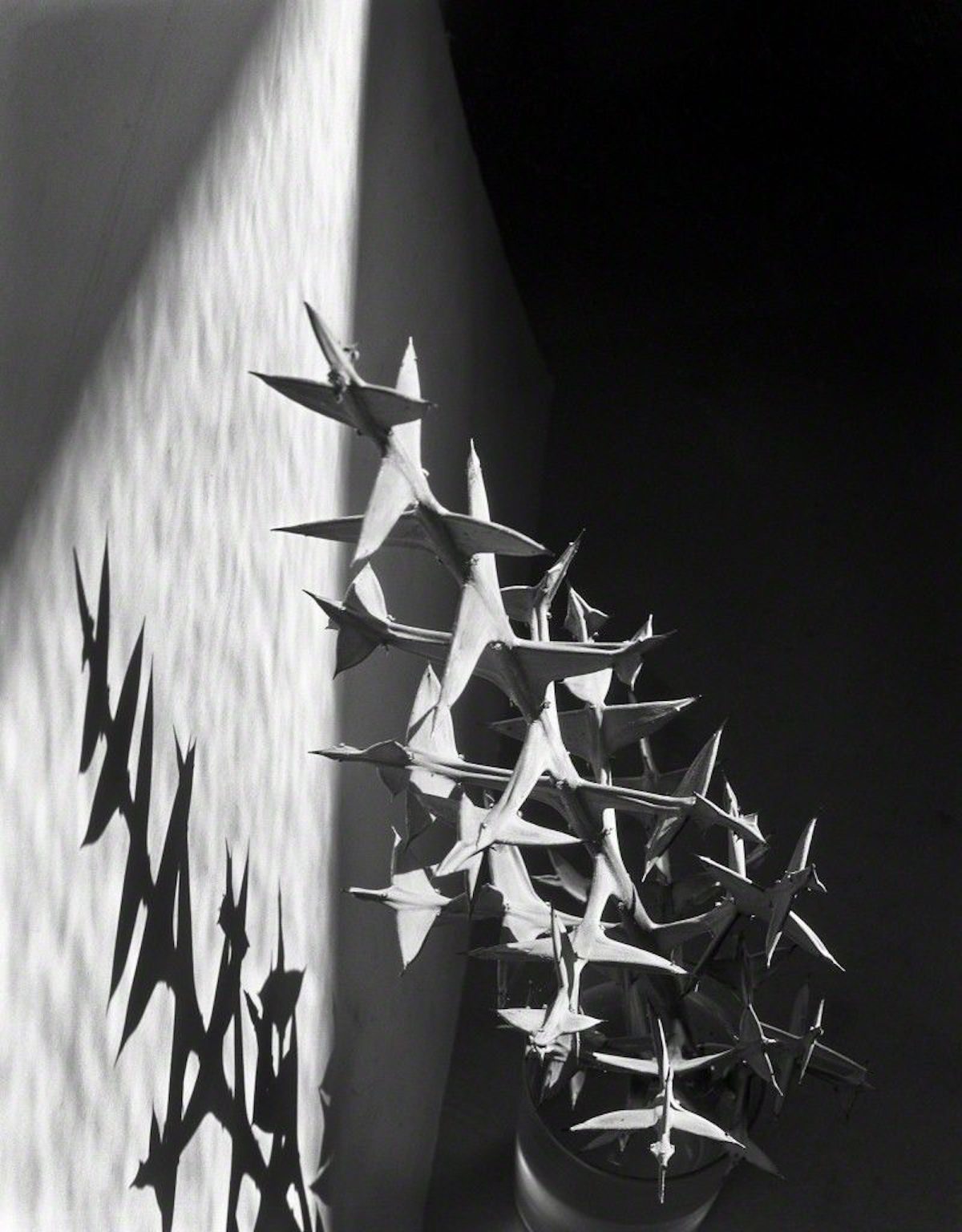

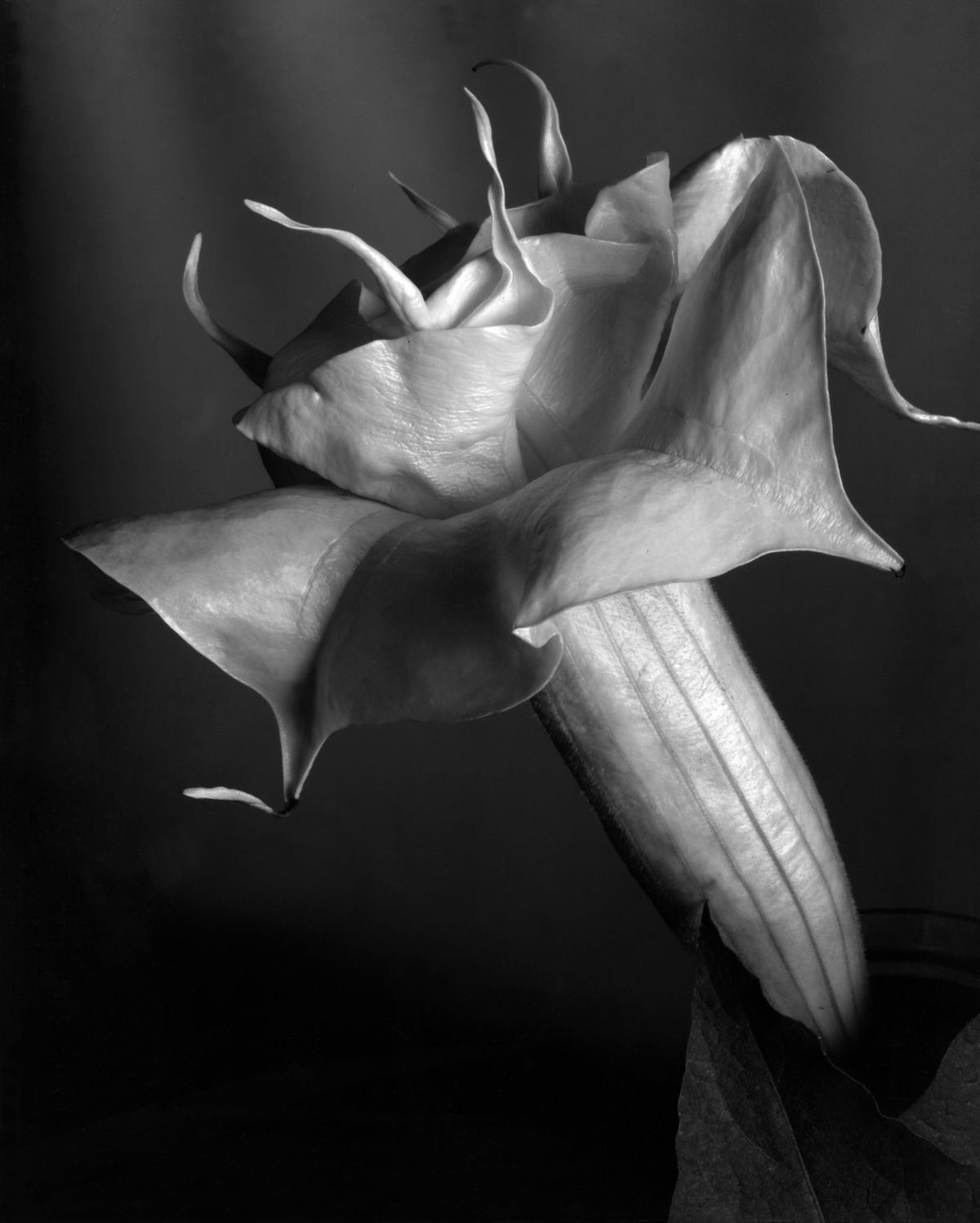

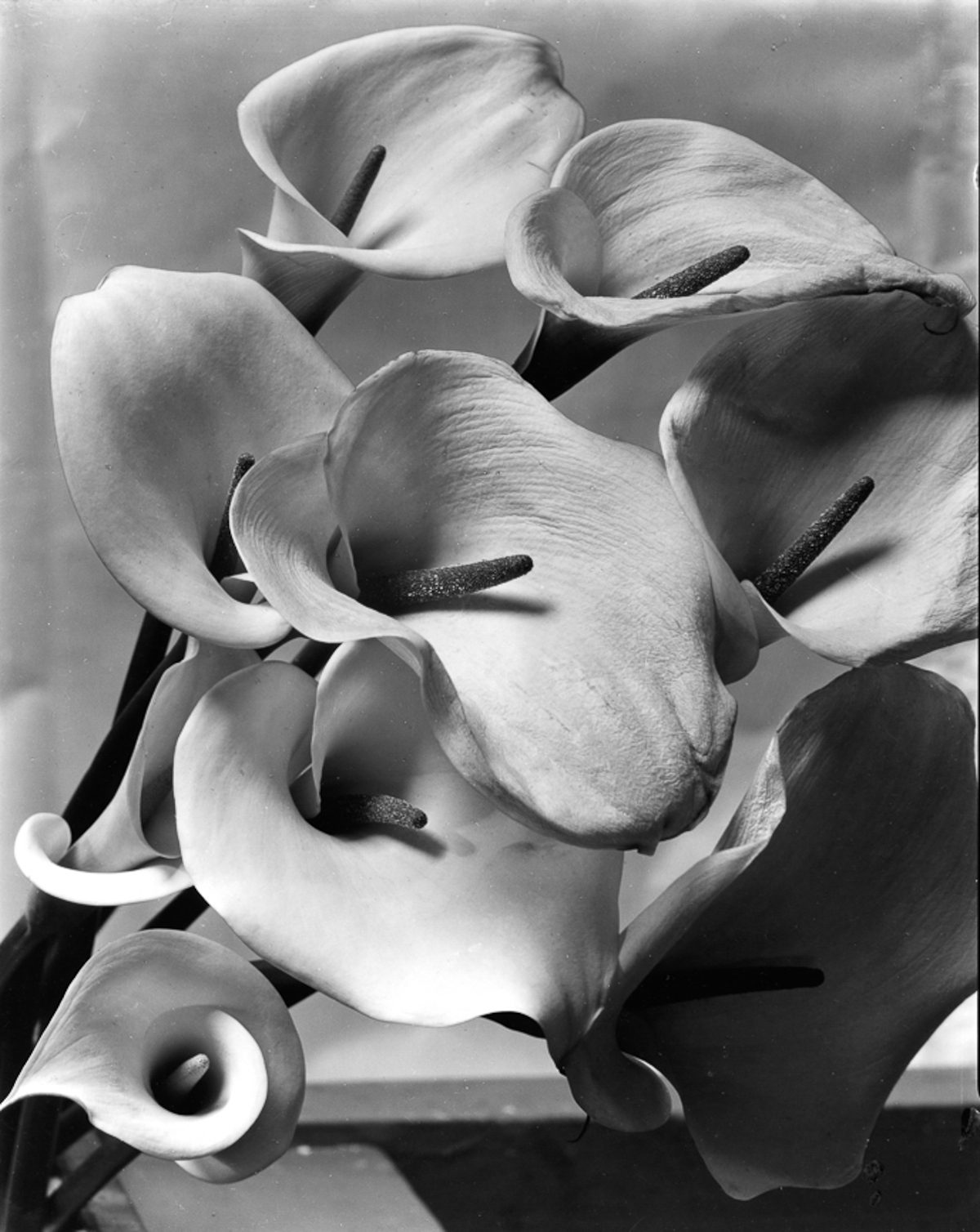

Imogen Cunningham’s close-up botanical photographs, taken during the 1920s and 30s, have been compared to Georgia O’Keeffe’s abstract flower paintings made around the same time, but the resemblance may have little to do with influence. Cunningham co-founded Group f/64 in San Francisco with Ansel Adams and Edward Weston as a West Coast answer to the modernism of O’Keeffe’s husband Alfred Stieglitz. But where Stieglitz and O’Keeffe moved toward greater abstraction, Cunningham and her colleagues strove for documentary precision, to show the world, said Weston, “as it is.”

“The camera should be used for a recording of life,” Weston elaborated, “for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.” These stated aims are evident in high-contrast, sharp-focus landscapes, nudes, portraits, and industrial photos taken by the eleven photographers of Group f/64, named for the smallest aperture setting on a camera at the time. Cunningham might have had the most scientific eye of them all—having studied photographic chemistry in the U.S. and Germany. But the “formula for doing a good job in photography,” she said, “is to think like a poet.” That she did as well, in a career that spanned over half a century.

The inspiration for her flowers, Cunningham noted, came from the frustrated constraints of motherhood. “The reason during the twenties that I photographed plants was that I had three children under the age of four to take care of, so I was cooped up. I had a garden available and I photographed them indoors. Later when I was free, I did other things.” If it sounds like she disparaged her plant photographs, there may be good reason she did not wish to be known primarily for them, acclaimed though they were (so sharp and clear, they were licensed for reproduction in botanical textbooks).

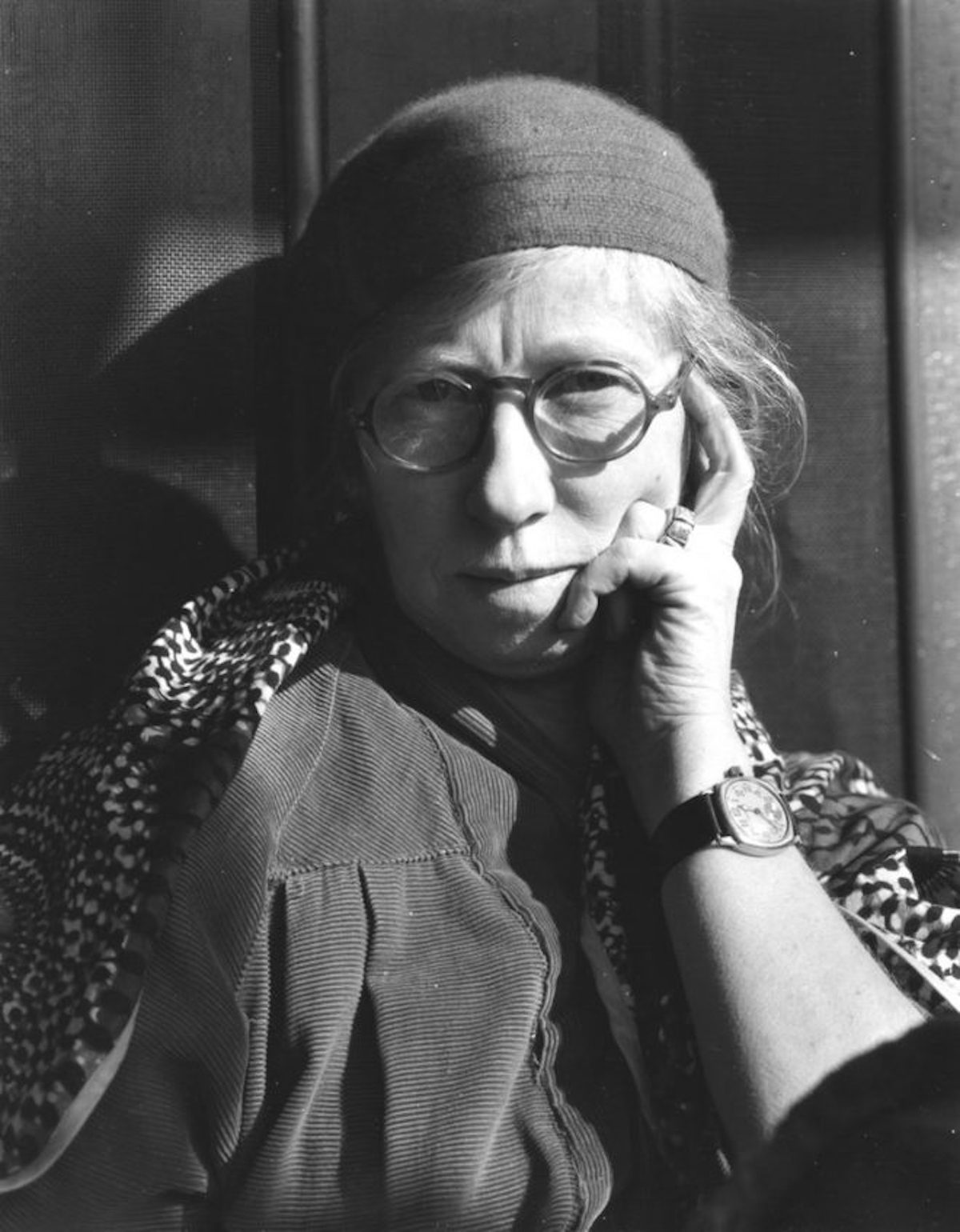

Cunningham “struggled,” the Huxley-Parlour gallery notes, “to have her work judged as comparable to that made by the male members of the group. She felt patronized and frustrated when Adams said that ‘her prints could have been produced only by a woman, which does not imply they lack vigor.’” Adams and Cunningham were lifelong friends, but “they were an odd couple,” Steve Meltzer writes at Imaging Resource. “He was formal, reserved and conservative while she was blunt, a free spirit and a radical. ‘There are certain things you don’t discuss with Ansel, especially if you don’t agree,’ Imogen said.”

She stressed self-reliance and did not want gender to limit her options. In an article titled “Photography as a Profession for Women,” Cunningham encouraged other women to learn the craft, “not to outdo men,” the Museum of Northwest Art writes, “but to try to do something for themselves.” Women who have struggled to succeed in professions dominated by men might recognize what Adams described as her caustic response to criticism. “I used to say that Imogen’s blood was three percent acetic acid,” Adams remarked. “She seemed to have an acid reaction to so many things.”

Born in 1883 in Portland, Oregon and raised in Seattle, Cunningham found a partner and husband in Seattle artist and printmaker Roy Partridge. During an outing on Mt. Rainier, both stripped in freezing temperatures and Imogen took photographs of Partridge in the nude. When she published them in 1914, it caused a minor scandal, though “the opposite practice was quite acceptable,” Meltzer points out. One critic wrote “a terrific tirade on my stuff as being very vulgar,” she recalled. “It didn’t make a single bit of difference in my business. Nobody thought the worse of me.”

Initially inspired by the soft-focus Pictorialism of the early 20th century—especially Gertrude Käsebier’s mother and daughter portrait, Blessed Art Though Among Women—Cunningham gravitated toward portraiture and opened her own successful studio. Her move toward stark, modern photos of natural and industrial subjects meant a significant shift in style, but it did not mean she turned away from human subjects. “The fascinating thing about portraiture is that nobody is alike,” she said. She took self portraits and nudes throughout her life, photographed artists like Frida Kahlo, Man Ray, and Gertrude Stein, and in the 1930s, was invited to Hollywood, where she took pictures of the stars. Asked what she wanted to photograph when she arrived in L.A., she answered, in typically contrarian style, “Ugly men.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.