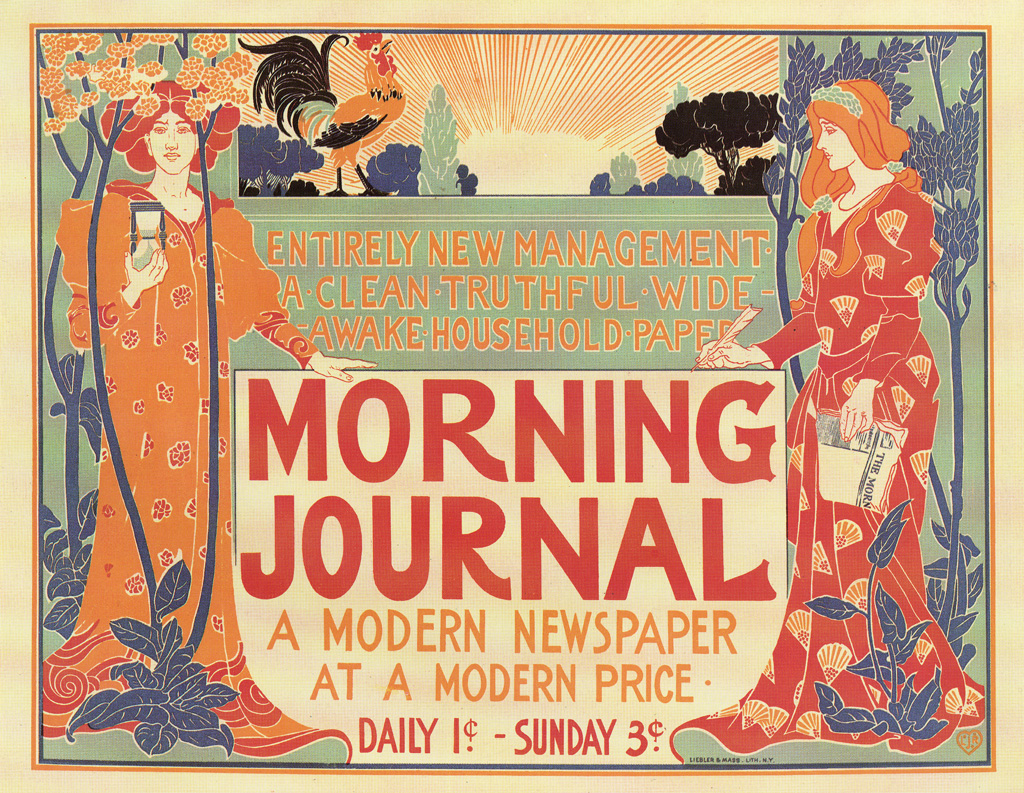

The explosion of creative activity in Europe and the U.S. from the end of the 20th century to the eve of World War I produced incredible architecture, art, music, and literature. Vital aesthetic innovations made their way into the commercial sphere through posters and advertisements by artists inspired by the pre-Raphaelites and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. Such works of graphic art now generally represent La Belle Epoque, an age viewed in the popular imagination as one of refinement and industrial progress. The impression is not a mistaken one, exactly, when viewed through a certain class lens.

On the other hand, Mark Twain’s term “the gilded age” also characterizes the time, when a gold veneer covered historic inequality and social unrest. The decades preceding the Great War can be characterized, as one writer argues, “by the very rich’s inability to deal with the grim reality of modern life” and a “retreat into a frivolous, fairy-tale kind of existence of their own making.” Aristocratic values upheld standards of beauty that had little to do with how the majority of people lived. Top-heavy industrialized societies threatened to collapse as they spread themselves thin with imperial conquests and extravagant lifestyles.

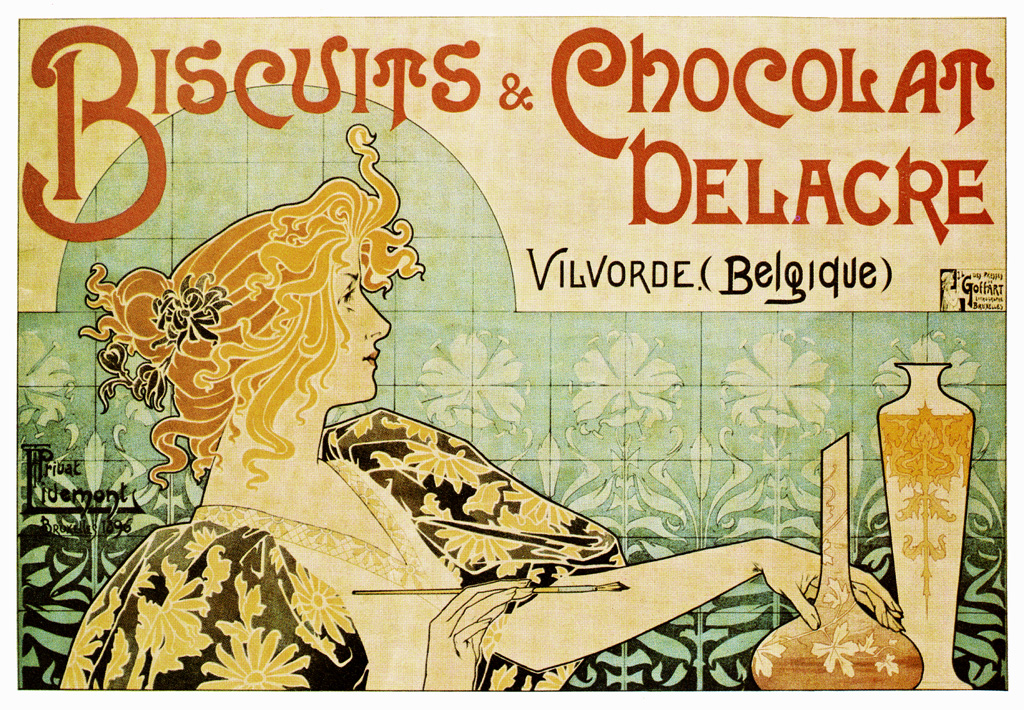

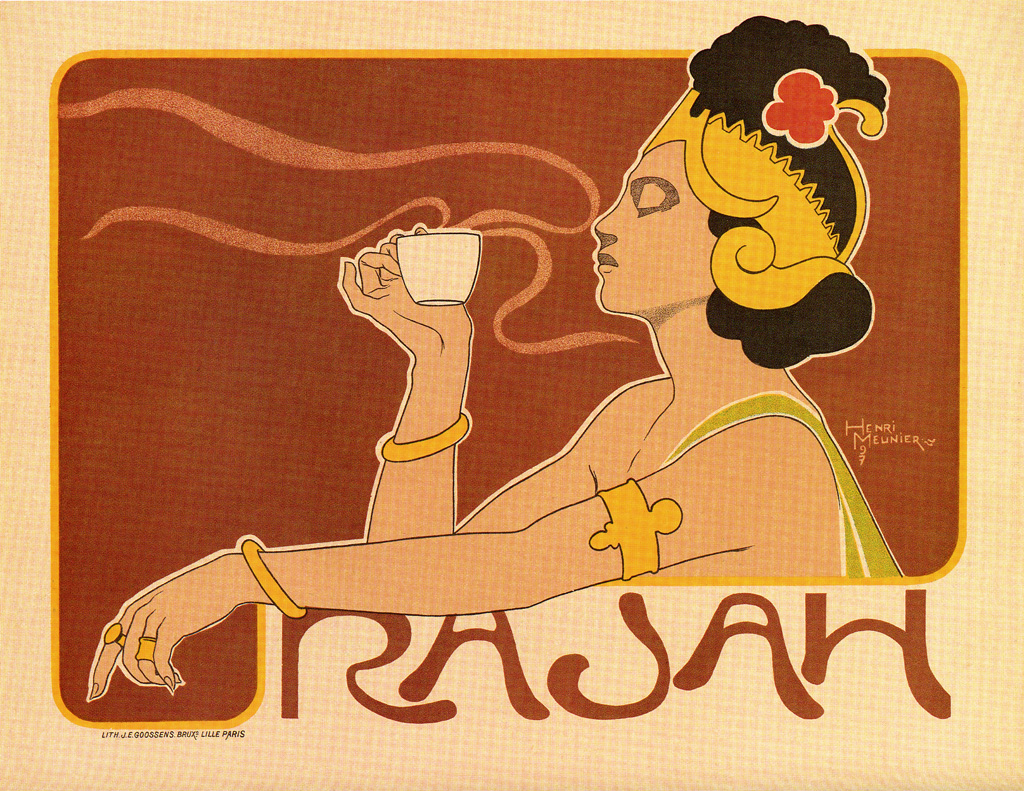

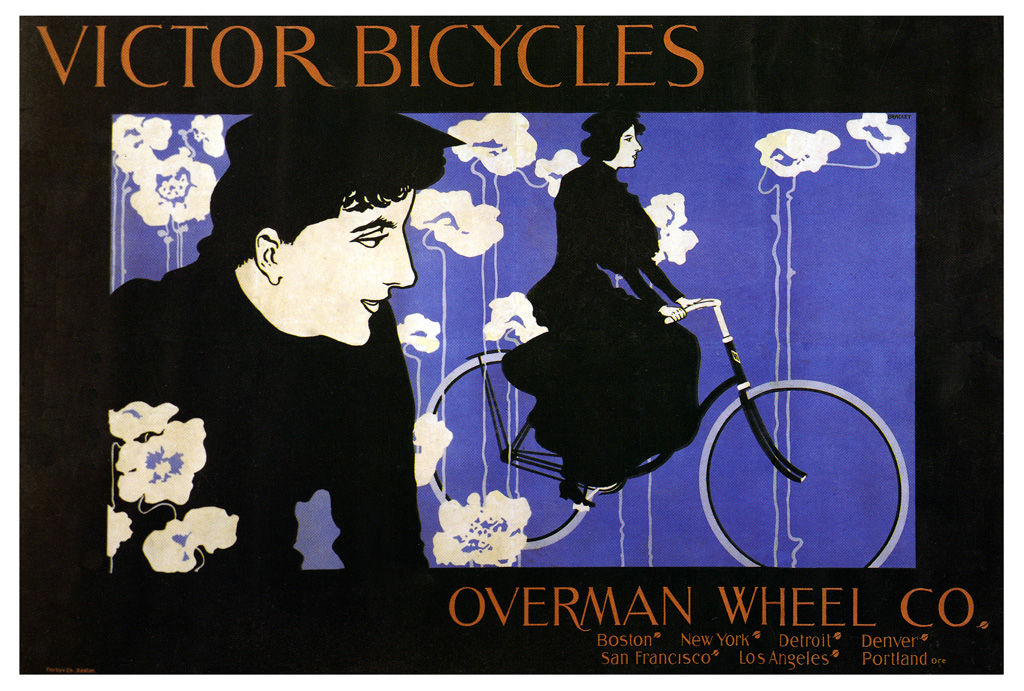

Commercial art of the period generally participated in the widespread denial of increasingly ugly social conditions, presenting a detached world of luxury products and leisure crafted from myth, folk tales, and exotic fantasies. As anarchists bombed factories and assassinated heads of state and industrial workers suffered under the realities of long hours, low pay, ill-health, and insecurity, poster art presented a world of gorgeous escape. Still, the anxieties of the time occasionally seeped into the world of art nouveau.

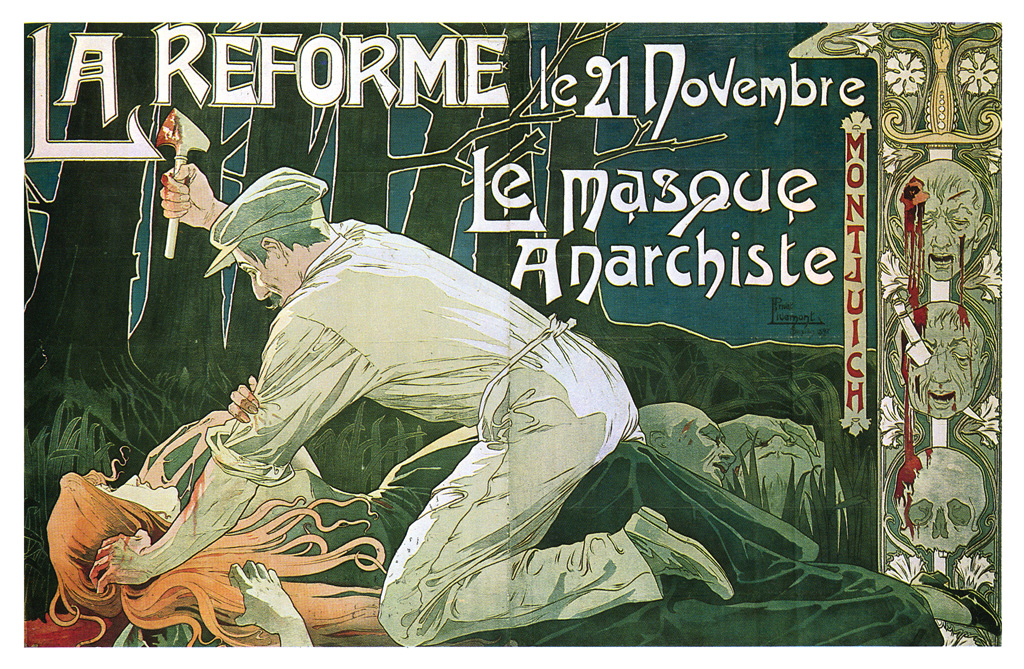

In the 1897 poster above by Henri Privat-Livemont for The Anarchist Mask, a serialized novel about class warfare, a villainous anarchist murders a woman with a hatchet, in a scene reminiscent of John Everett Millas’ 1851 painting Ophelia, a work exemplifying the Victorian cult of tragic beauty. Even as fears of social unrest enter the picture, they becomes a backward-looking aesthetic object, recalling Edgar Allan Poe’s famous contention that “the death… of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world.”

Such occasional gothic shadows aside, the art nouveau posters of the La Belle Epoque—whether selling newspapers, coffee, liquor, or bicycles—offer light, stylish examples of commercialized high culture, their vividness enabled by mass-produced zinc plates, an innovation that allowed lithographers to use multiple plates with different colors. They show us a mask of beauty and self-assurance covering rapid political and technological change and social instability.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.