“In photography, like in all things, there are people who can see and others who cannot even look.”

– Felix Nadar

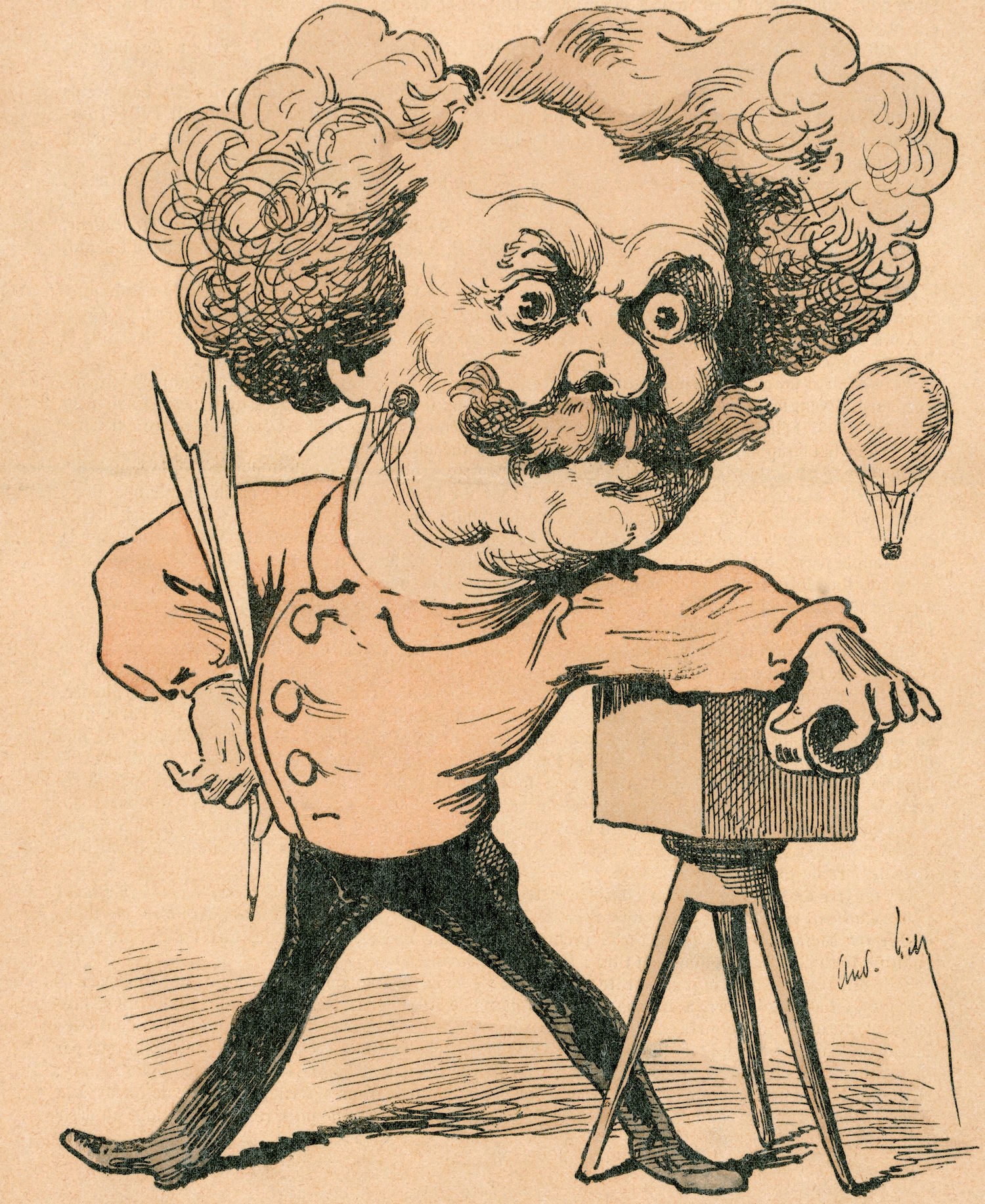

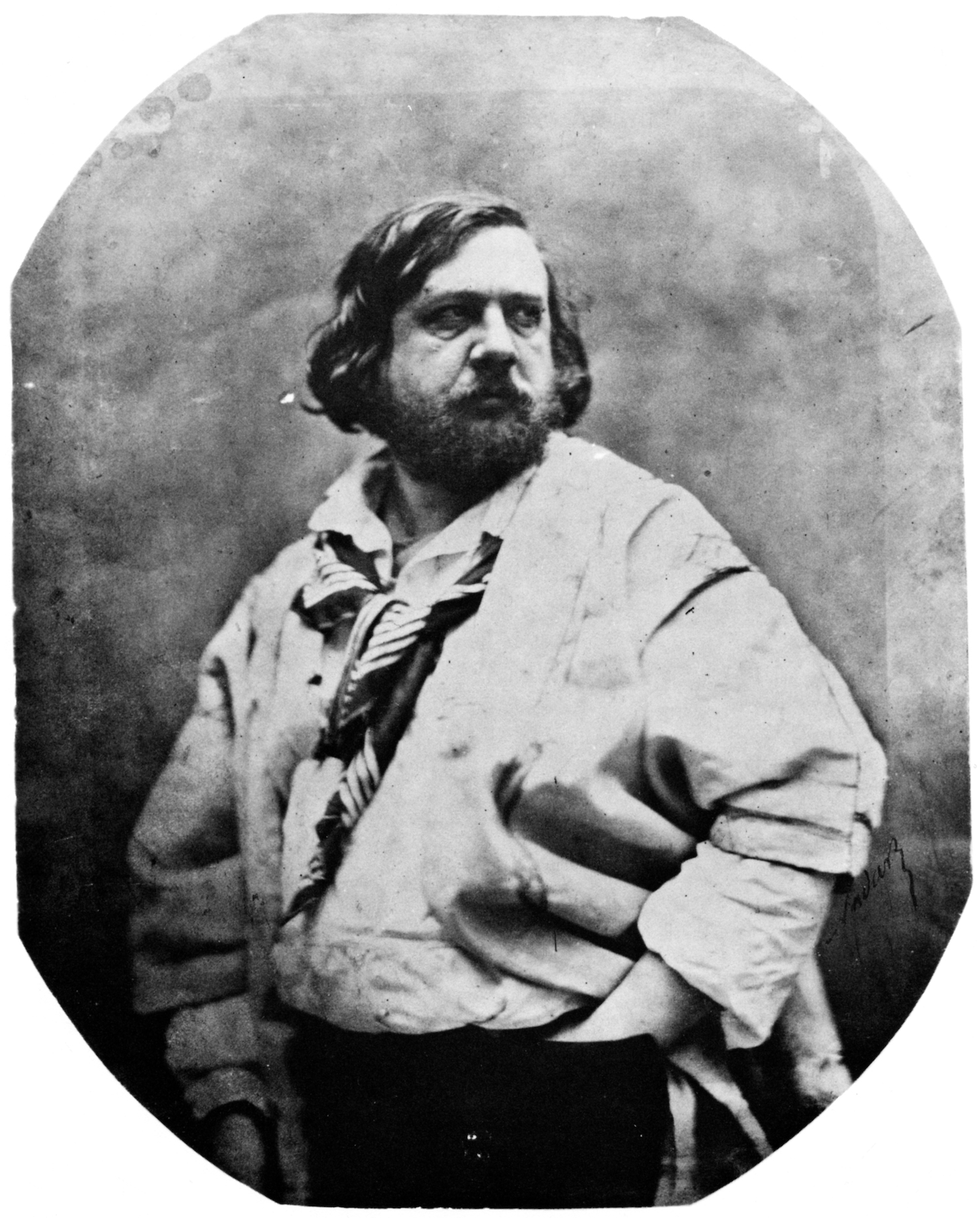

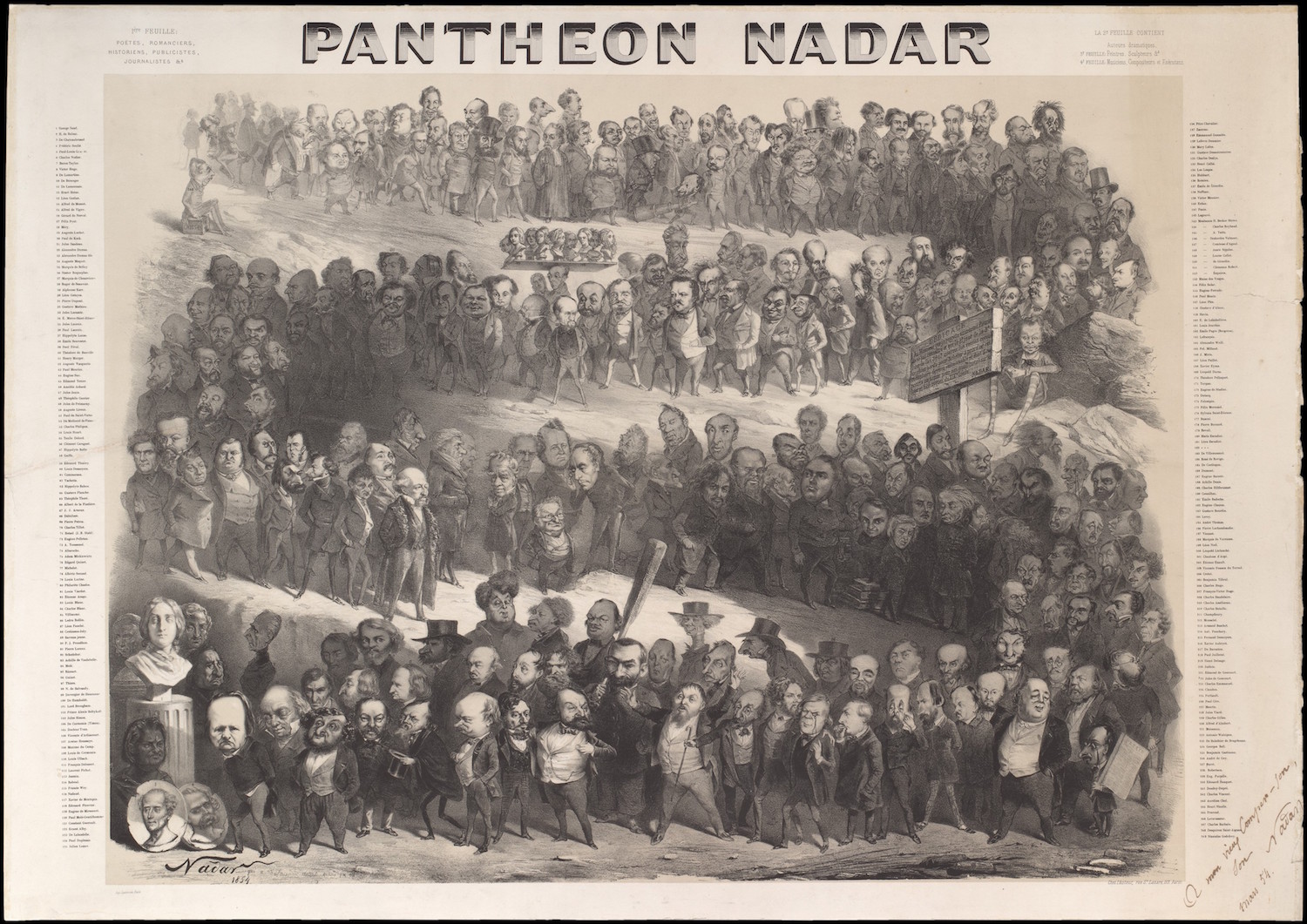

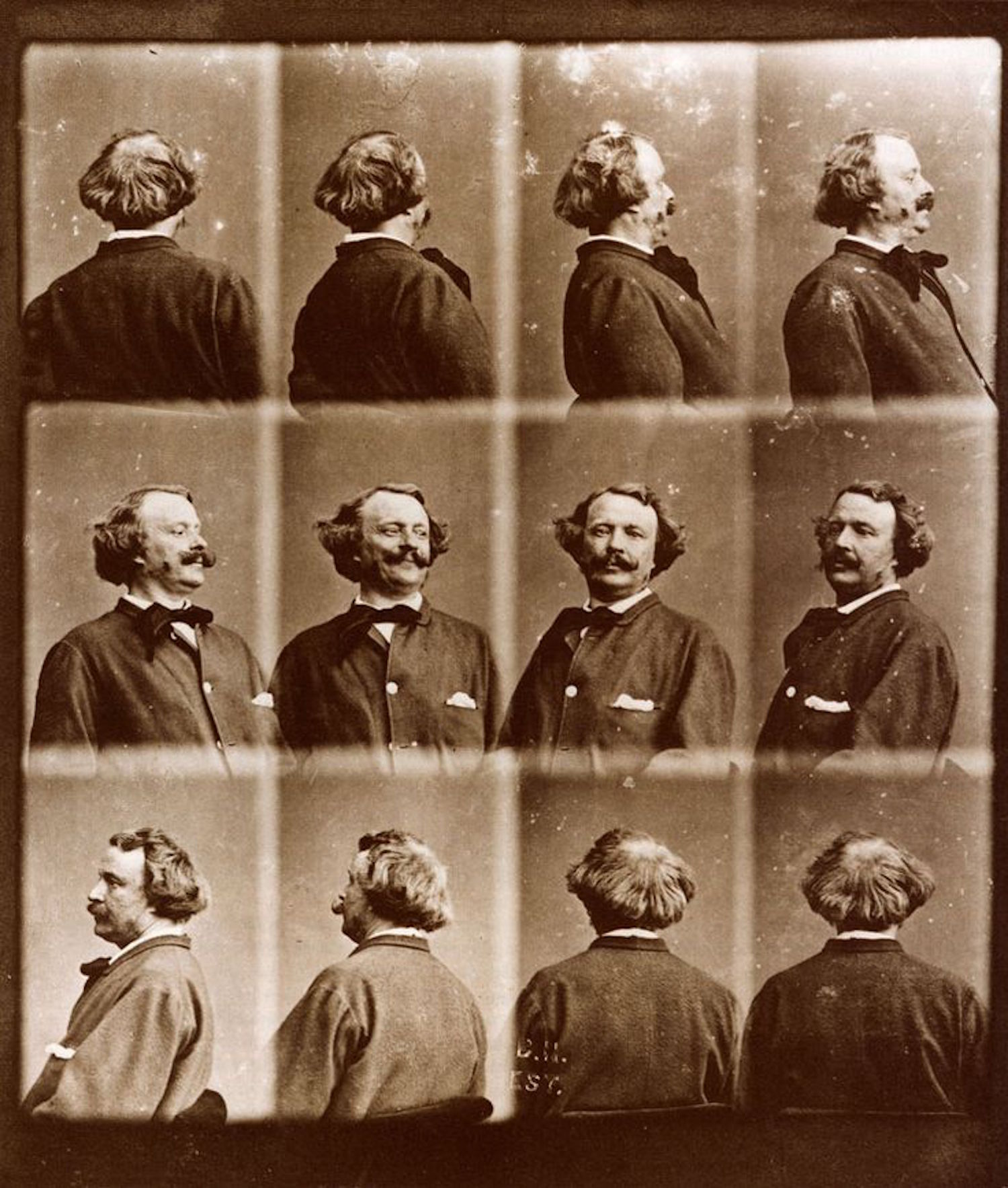

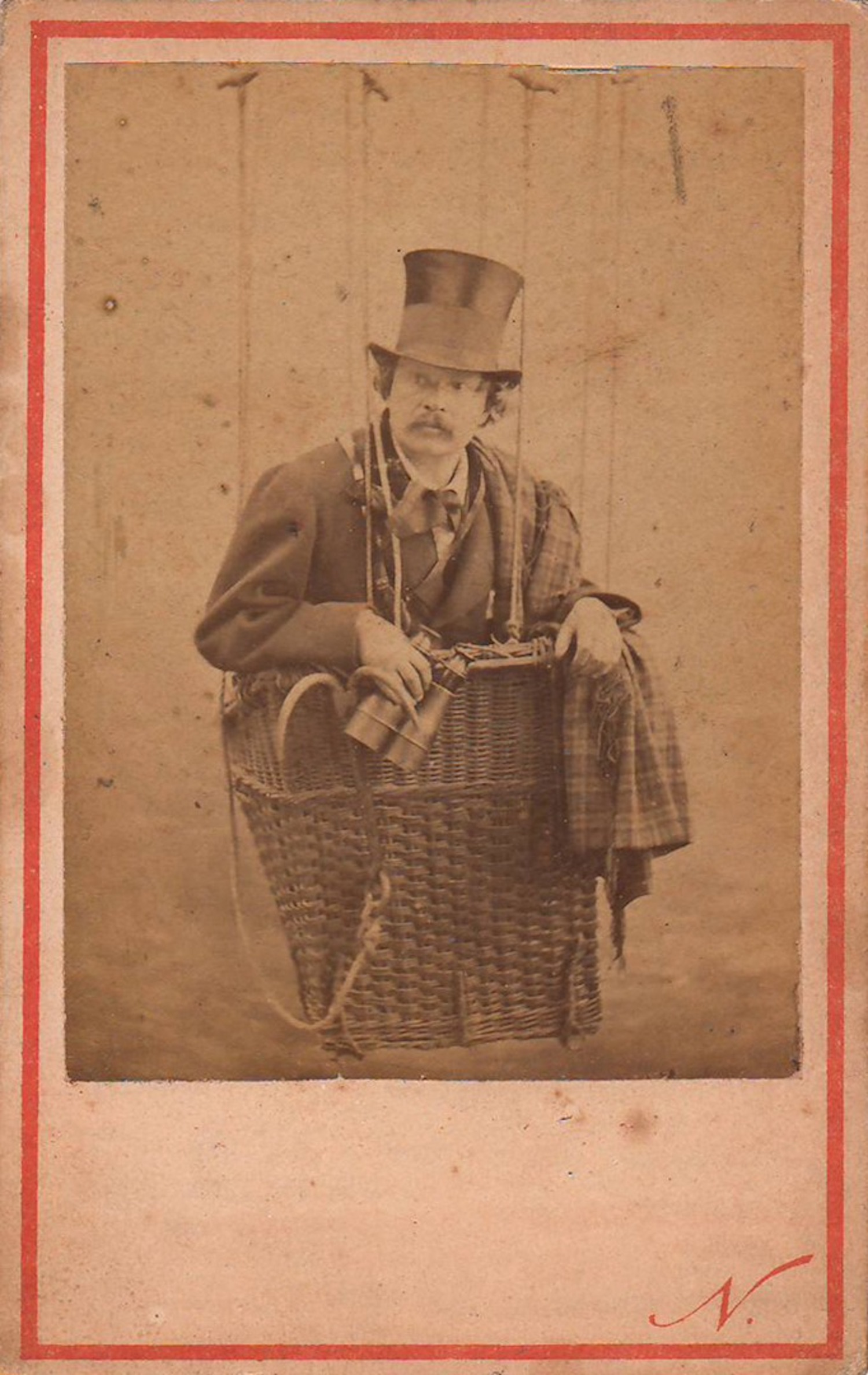

Félix Nadar (April 6, 1820–March 20, 1910 – nee Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) gained a place in the annals of photographic pioneers in 1858 when he became the first person to take an aerial photograph from a hot air balloon flight. A few years later, whilst working in the Paris catacombs, Nadar pioneered the use of artificial lighting in photography. He was also a journalist, author and deft artist, creating caricatures of the great and good. His Pantheon Nadar (1854) lampoons hundreds of notable Parisians.

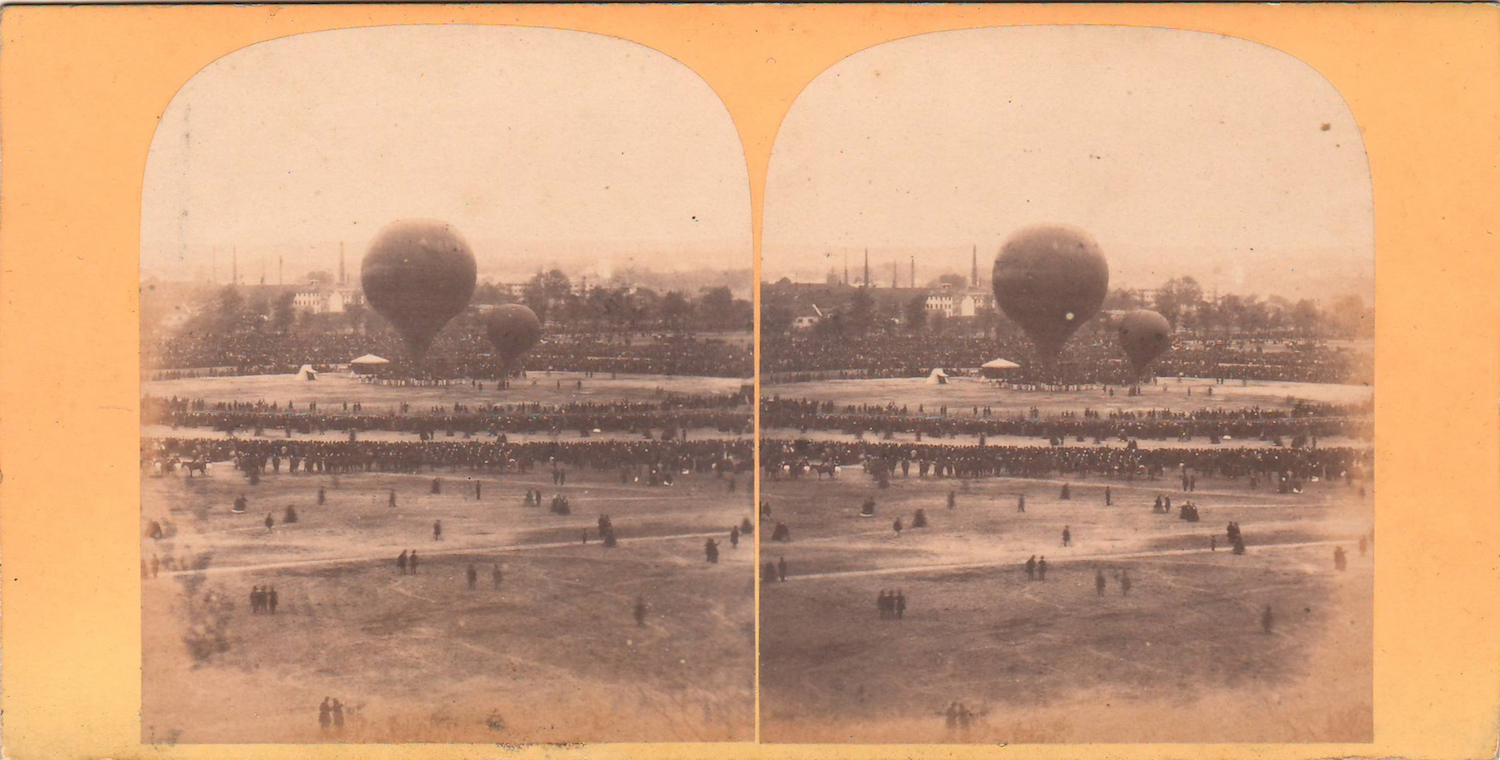

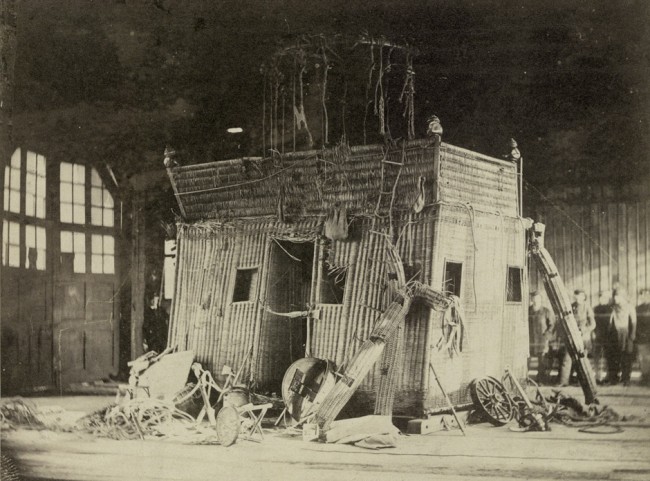

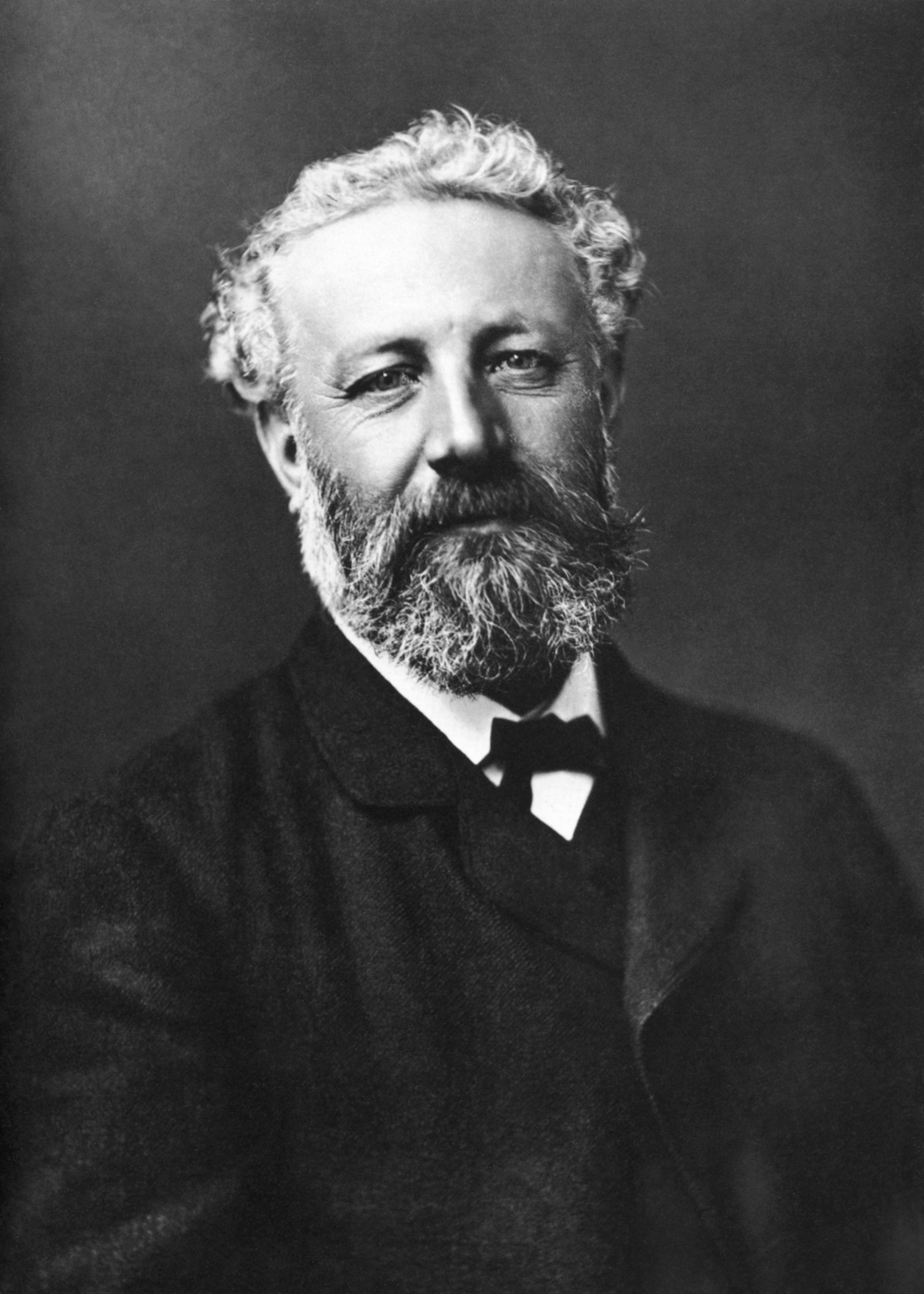

In 1863, Nadar furthered his studies into “heavier than air machines” by constructing a gigantic (6000 m³) balloon named Le Géant (The Giant), which inspired author Jules Verne’s Five Weeks in a Balloon. (The device intended to show how poor an idea balloon travel was is recorded by Nadar in his 1864 tome À terre et en l’air… Mémoires du Géant. The second ascent was punctuated with a crash-landing that dragged on for half an hour, as the balloon bounced through the French countryside. “When he wants to,” Nadar writes in Le Droit au Vol (The Right to Flight), “man will fly like a bird, better than a bird – because … it is certain that man will be obliged to fly better than a bird in order to fly just as well.”)

Nadar and Verne would collaborate further, hanging out together at the The Society for the Encouragement of Aerial Locomotion by Means of Heavier than Air Machines, an organisation based at Nadar’s studio. Nadar was President; Verne was club secretary. Nadar would be immortalised as Michael Ardan in Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon.

Verne was impressed to call his friend “an Icarus with replaceable wings”.

And here’s still more about Nadar’s life in the limelight:

Nadar is not only an important figure in the history of photography and aviation, but also in the history of painting. He held the first impressionist exhibition in his Studio in 1874, providing a forum for the controversial art of Manet, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Cezanne, Pissarro, Sisley, Boudin and others. During his lifetime he championed and hosted exhibitions for many painters whose work he believed in.

And more:

Nadar interviewed Michel-Eugene Chevreul on the French scientist’s one-hundredth birthday. Nadar’s son Paul took the photographs. The photographs were printed consecutively with captions beneath each, in a double-page spread by the Journal Illustre on September 5, 1886. A composition of Nadar’s love of journalism and his knowledge of photography had created the first “photo-interview.”

Nadar was a terrific self-promoter and adopter of new things. “He is a man of wit without a shadow of rationality,” wrote the lithographer and journalist Charles Philipon (19 April 1800 – 25 January 1861). “His life has been, still is, and always will be incoherent.”

Little epitomises Nadar’s curious life more than the sequence of events that turned him into a society photographer.

Roger Cicala writes:

…a friend suggested Felix open a photography studio and offered to invest in it if he did. Felix was too busy to start a new venture, but he had a better idea. His younger brother Adrien was an unsuccessful portrait painter that Felix had to support. He paid for his brother to have photography lessons from Gustave Le Gray and set him up in a nice studio, at least partially funded by his friend.

According to Nadar’s later description, Adrien was a talented artist with poor work habits and little ambition. Not surprisingly, Adrien was no more successful at photography than he had been as a painter. Since his friend had loaned the money for the studio Felix felt obligated to make it successful, so he became an active participant in the studio. In his own words he “gave it everything I could: work, money, personal relations, and my pseudonym, which followed me.”

The studio became quite successful, but Adrien, who had not expected Felix to become an active partner, left and opened his own studio, calling himself Nadar Jeune (Nadar the Younger). Nadar was enraged at this and sued his brother senseless over the next three years. During the court proceedings, Felix Nadar made a short speech that still resonates today:

“The theory of photography can be taught in an hour; the technique in a day. What can’t be taught is the feeling for light; . . . it’s the understanding of this effect which requires artistic perception. What is taught even less is the immediate understanding of your subject . . . that enables you to make not just a dreary cardboard copy typical of the merest hack in a darkroom, but a likeness of the most intimate and happy kind.”

Adrien ended up disgraced and bankrupt. Of course, in a way that apparently only the French understand, Nadar, having bankrupted his brother, felt obligated to support him financially for the rest of his life.

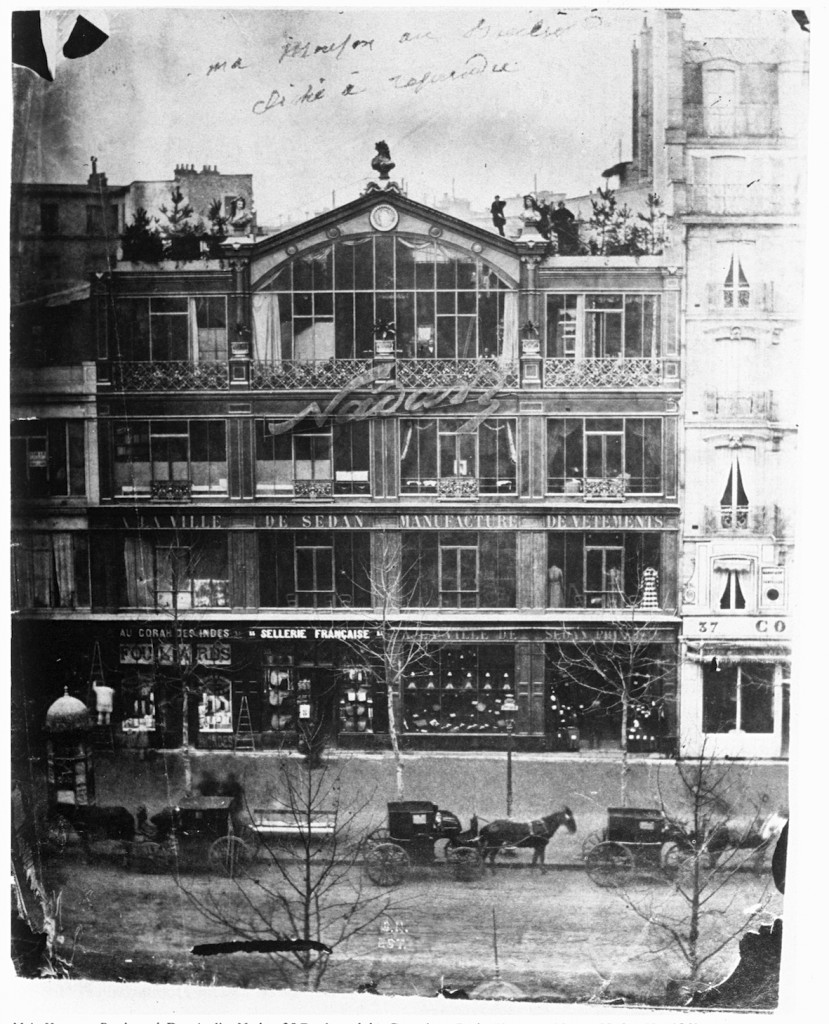

Nadar was a tall, large man with flaming red hair and a red mustache. Red was his color, and he capitalized on it. The exterior and interior of his studio were red, and consisted of two floors decorated with valuable art and porcelain. His name was written in large red gaslight letters across the front of the building. Nadar wore a resplendent red velvet robe to greet his clients.

His images were bordered in red.

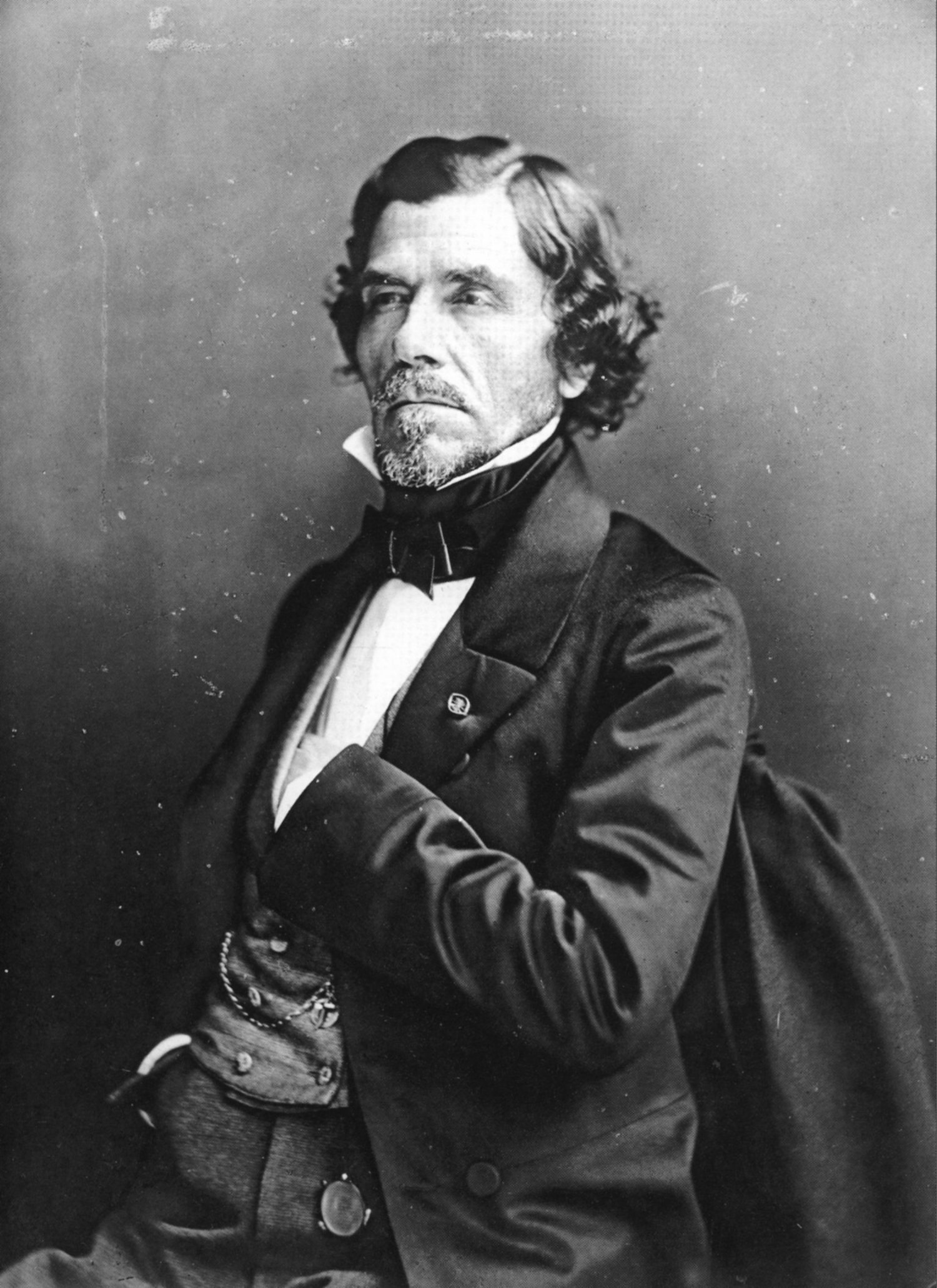

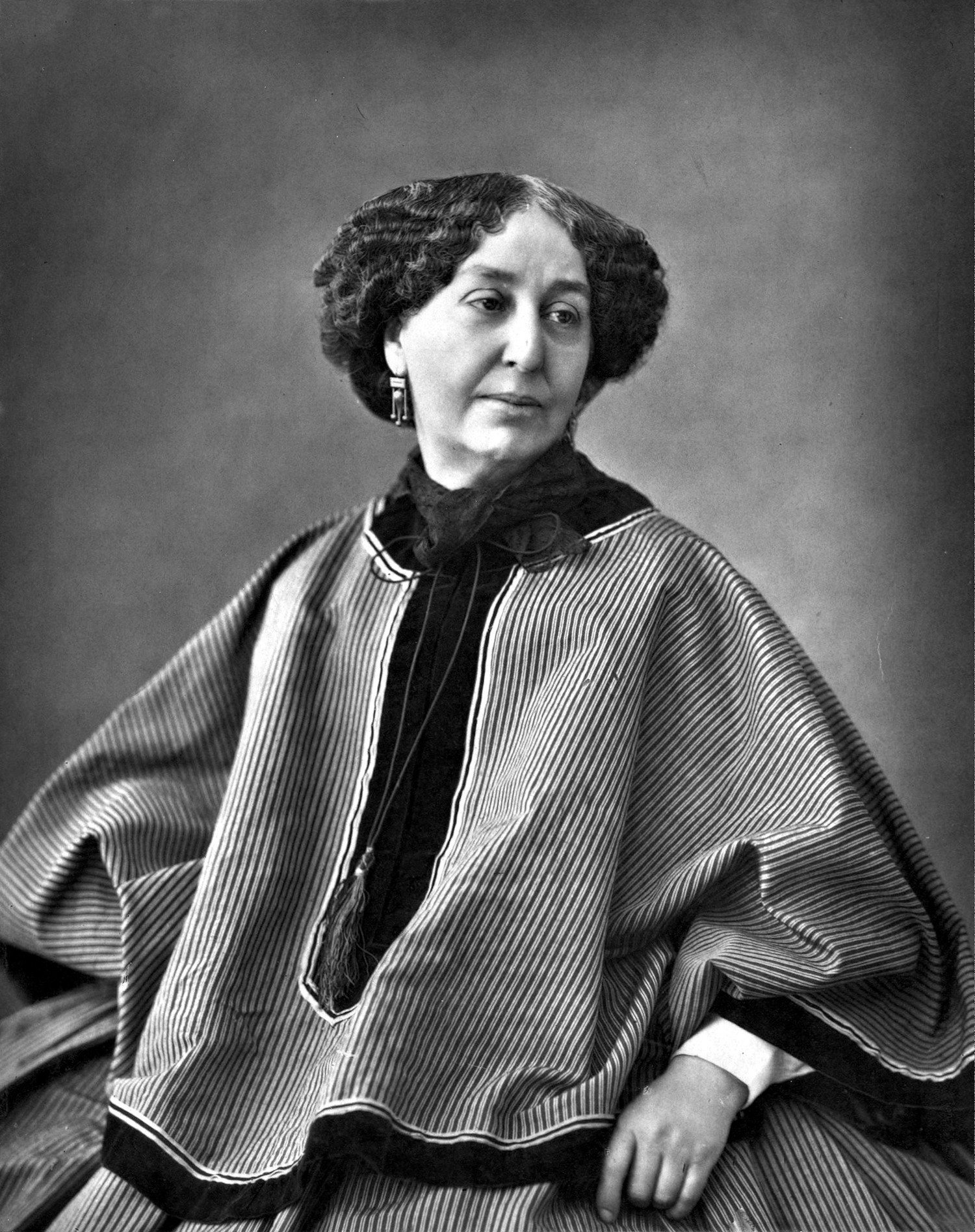

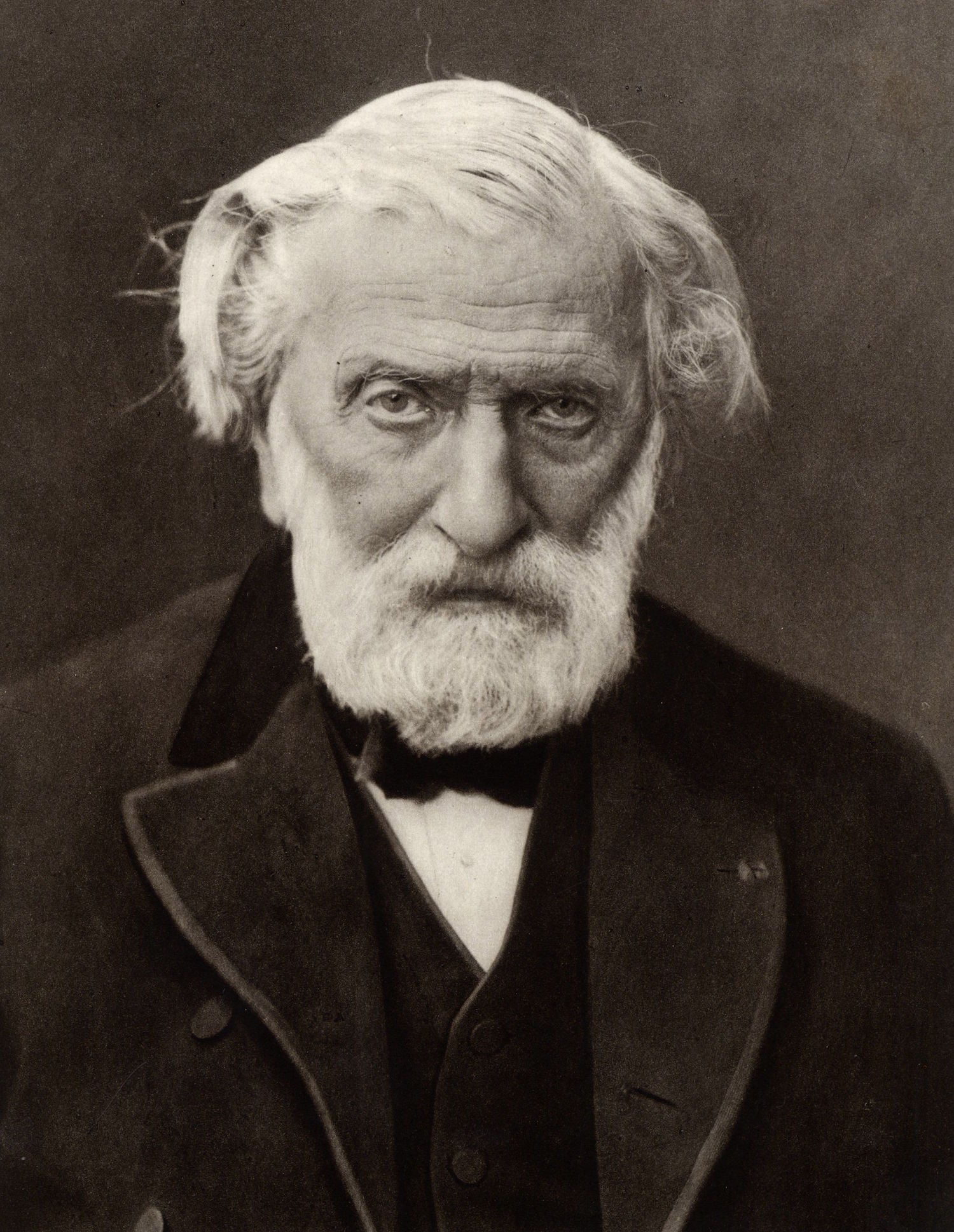

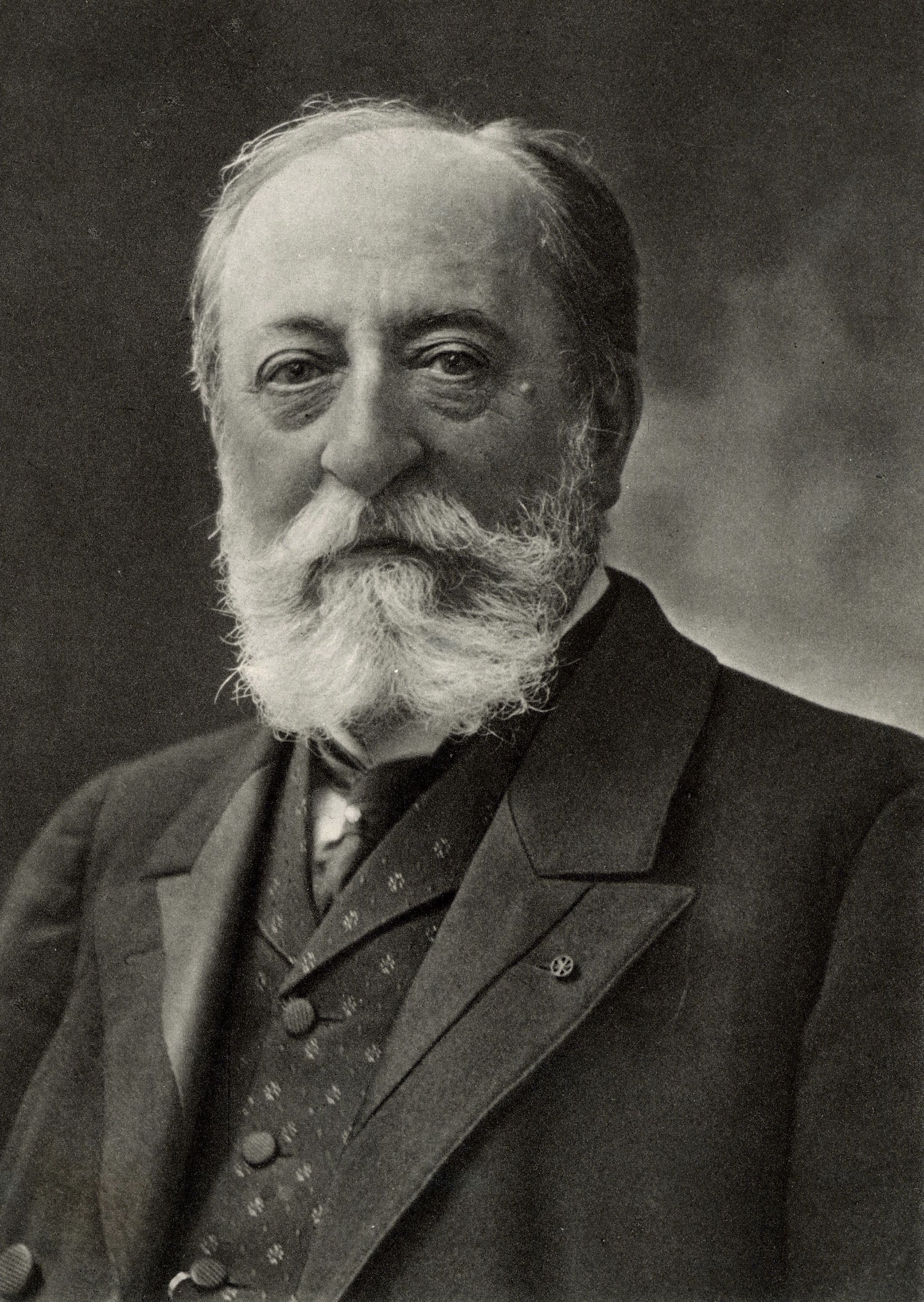

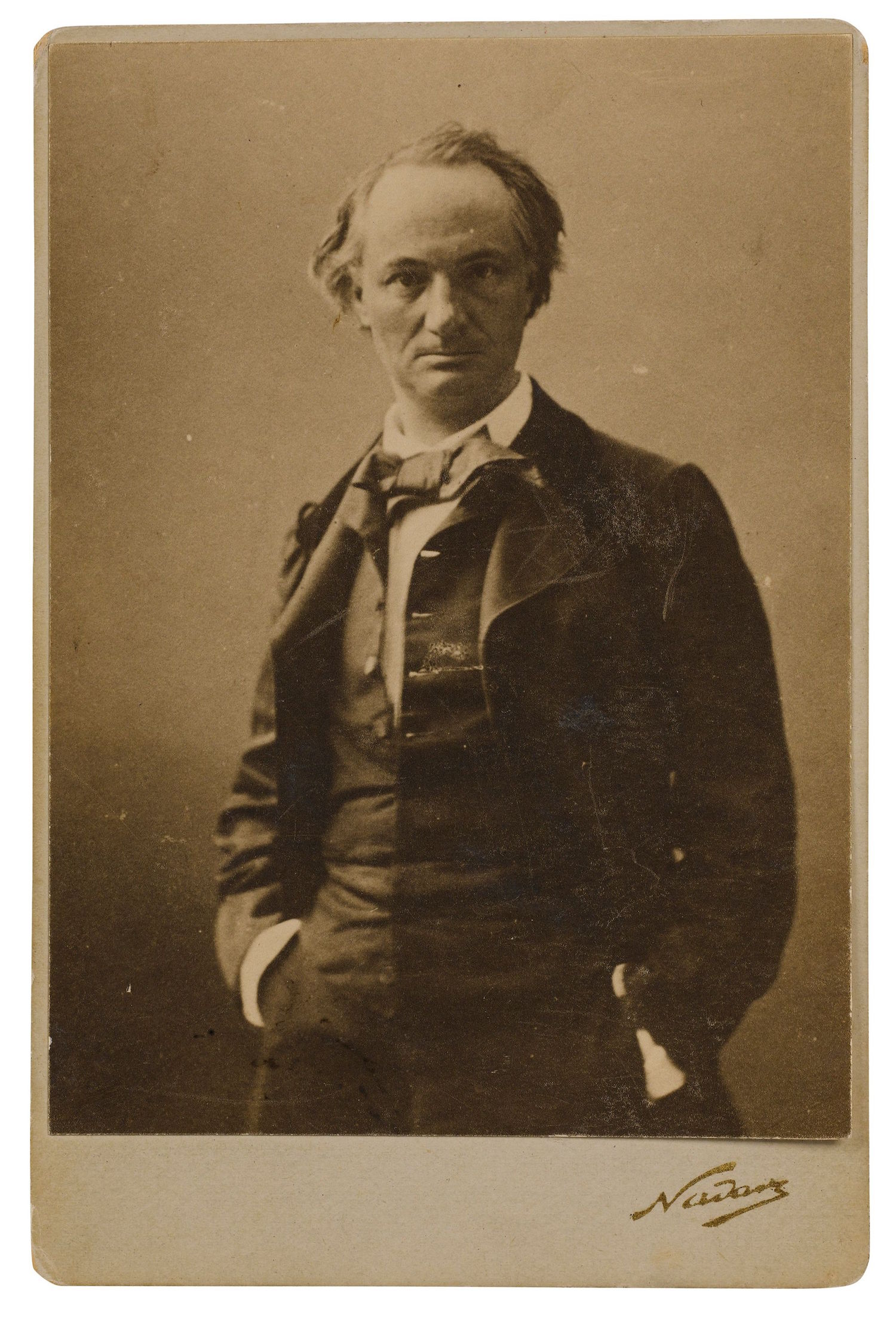

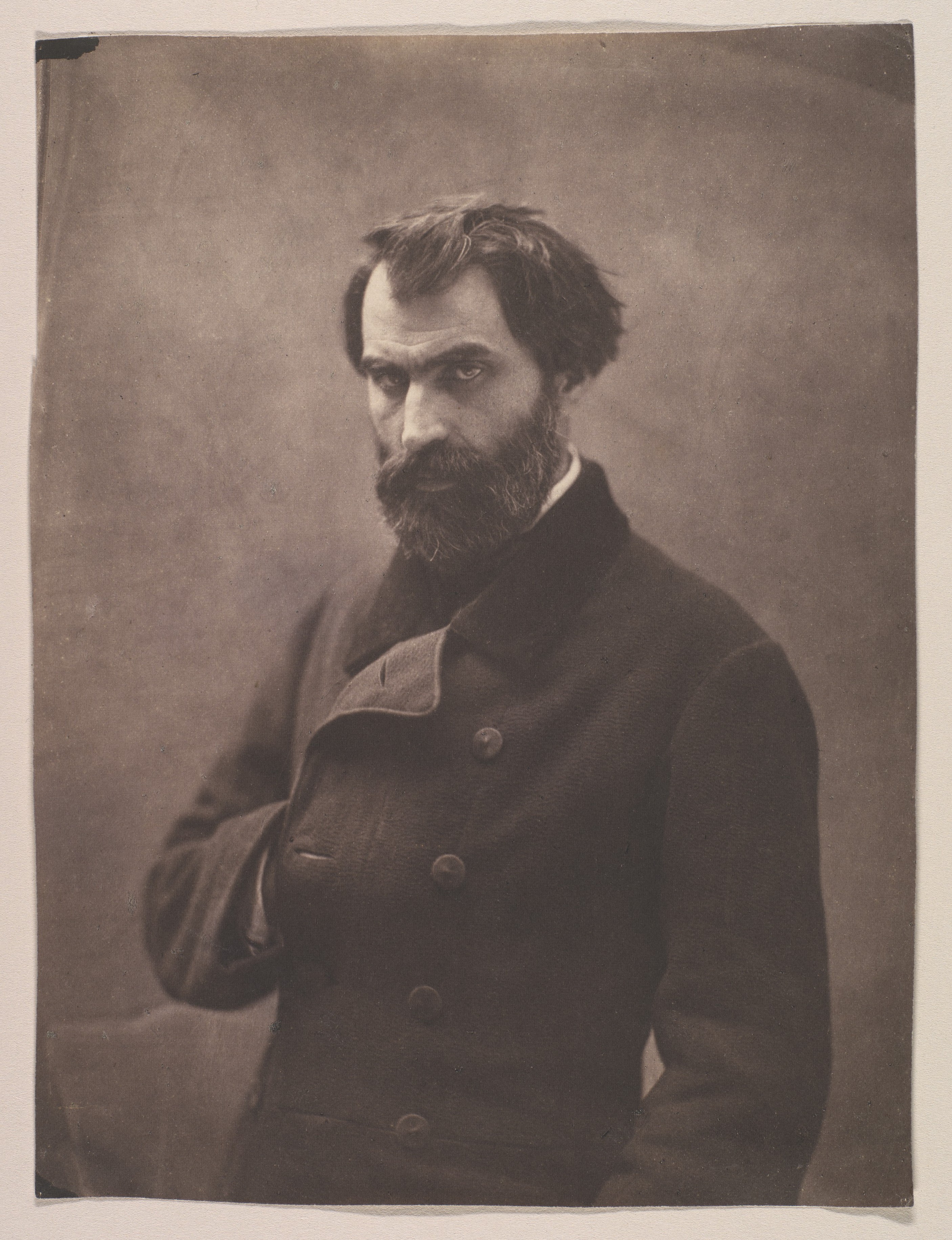

In Quand j’étais photographe (When I Was a Photographer), written when Nadar was 80, we read his life-learned observations, formed during his meetings with his subjects, such as Gustave Doré, the aforementioned Verne, Sarah Bernhardt, Eugène Delacroix, George Sand, Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac. Pretty much every noteworthy performer, writer, artist and musician in the second empire was photographed in Nadar’s studio.

Nadar understood the power of the new visual art form. “To produce an intimate likeness rather than a banal portrait, the result of mere chance, you must put yourself at once in communion with the sitter, size up his thoughts and his very character,” Nadar said about photography.

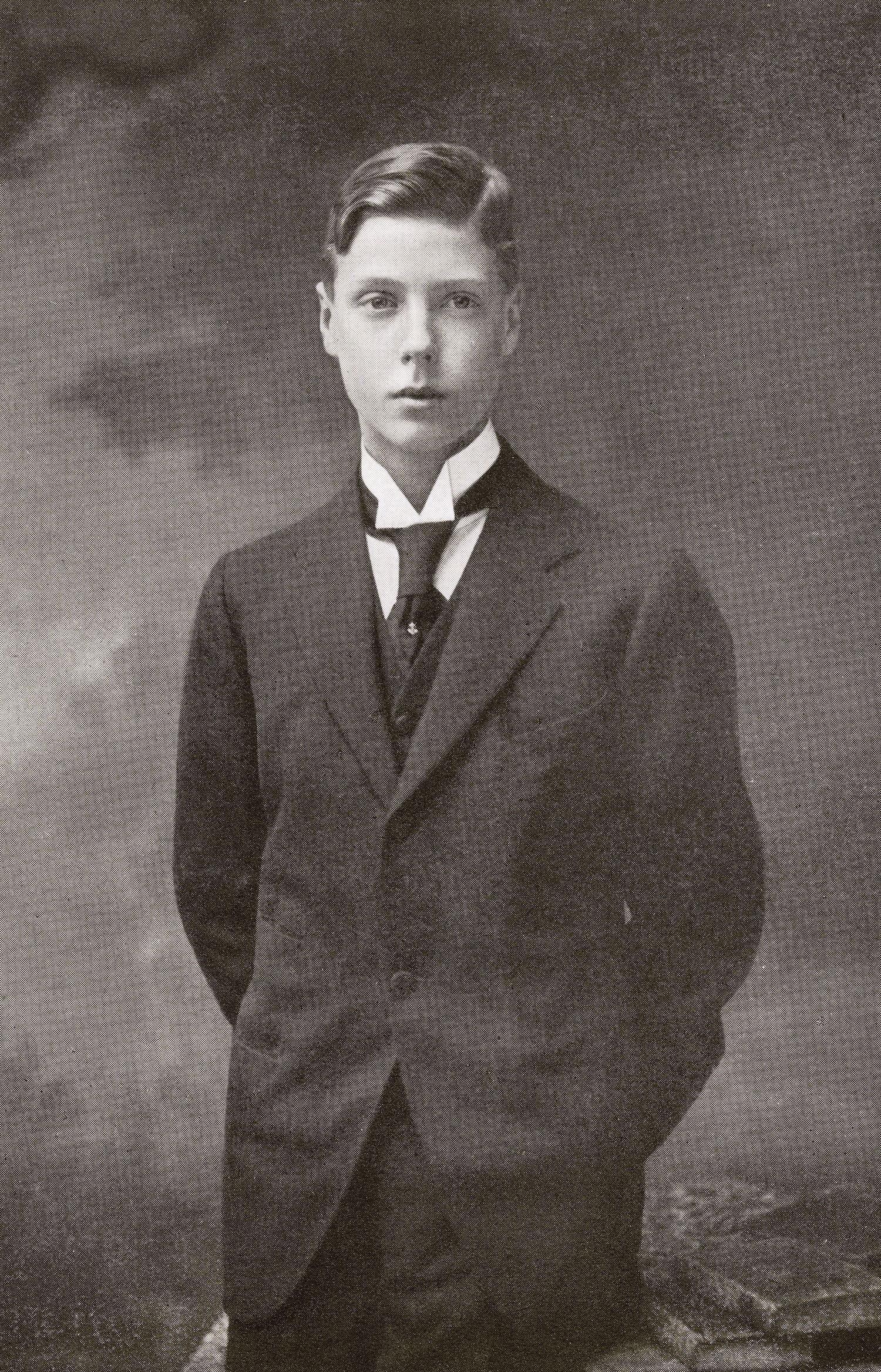

Hrh Prince Edward 1894 To 1972 King Of England Full Name Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David From The Book The Year 1912 Illustrated Pub. Lon. 1913

In the chapter Homicidal Photography, Nadar talks of a 1882 murder to illustrate the power of photographic images. A pharmacist killed his wife’s lover with the help of the wife and brother and tossed the body in the Seine river. Nadar was affected by how a single police photograph of the victim’s bloated corpse aroused the crowd. “The whole mob set to barking,” writes Nadar, “howling on this trail of blood.”

And then there was the time he defeated the Prussians:

One of the more amusing chapters in When I Was a Photographer tells the story of how, when Paris was besieged by the Prussians in 1870, Nadar established the world’s first airmail service, organising a fleet of balloons to float sacks of correspondence over enemy lines. There was one problem with the scheme: the mail could get out (as long as the balloon landed beyond the reach of the Prussian forces), but because balloons can’t be steered, return mail couldn’t be sent back in.

The ingenious solution, proposed to Nadar by an anonymous citizen, was photographic – or, to be precise, micrographic. The return correspondence was photographed on microfilm and the tiny negative strapped to a carrier pigeon’s leg. Once safely in Paris, the microfilm was enlarged, the precious letters distributed. “Our Paris, strangled by its anxiety over its absent ones,” Nadar writes, “finally breathed.”

Nadar’s balloons dropped cards on the enemy declaring “compliments to the Kaiser”.

But we are primarily interested in Nadar’s portraits.

At the heart of Nadar’s portraiture was his intuitive grasp of natural light and his skill at posing his subjects. He had learned a host of posing tricks from painter friends and he applied them to his photography. He would position his subjects in three-quarter views, hide their hands to emphasize their faces, and encourage them to find their own poses. Unlike other portrait photographers at the time, he rarely used props and he side lit his sitters to model their faces. He also controlled the quality of the light through the use of reflectors, screens, mirrors and even veils.

However, most importantly, he focused on his sitter’s gestures and glances and never tried to make “flattering” images of them.

“To produce an intimate likeness rather than a banal portrait, the result of mere chance, you must put yourself at once in communion with the sitter, size up his thoughts and his very character,” Nadar said about his craft.

On differences between female and male clients, he wrote:

So good is everyone’s opinion of his or her physical qualities that the first impression of every model before the proofs of his or her portrait is almost inevitably disappointment and recoil… Some people have the hypocritical modesty to conceal their shock under an appearance of indifference, but do not believe them.

We live in an age when narcissism is the norm. Nadar, who preferred not to photograph women because “the images are too true to nature to please the sitters, even the most beautiful”, thought men vain:

Nine times, I would even say eleven times out of ten, you will see that the wife is absorbed by the portraits of her husband, while the husband, no less hypnotized but by his own image, seems miles away from even thinking of the image of his other half.

This observation has been repeated too many times, and with mathematical precision, not to deserve to be at the head of these notes…

We have attributed to women the reputation of coquetry … but this constant solicitude of the effect provoked by our physical appearance, this coquetry, is even more reproachable in man himself…

Nothing in women can compare to the infatuation of certain men and to the constant concern about their “appearance” in the majority of them. Those who pretend to be the most detached in this matter are precisely the most affected.

I have found in men considered serious by everyone, in the most eminent personages, an anxiety, an extreme agitation, almost an agony in regard to the most insignificant details of their appearance…

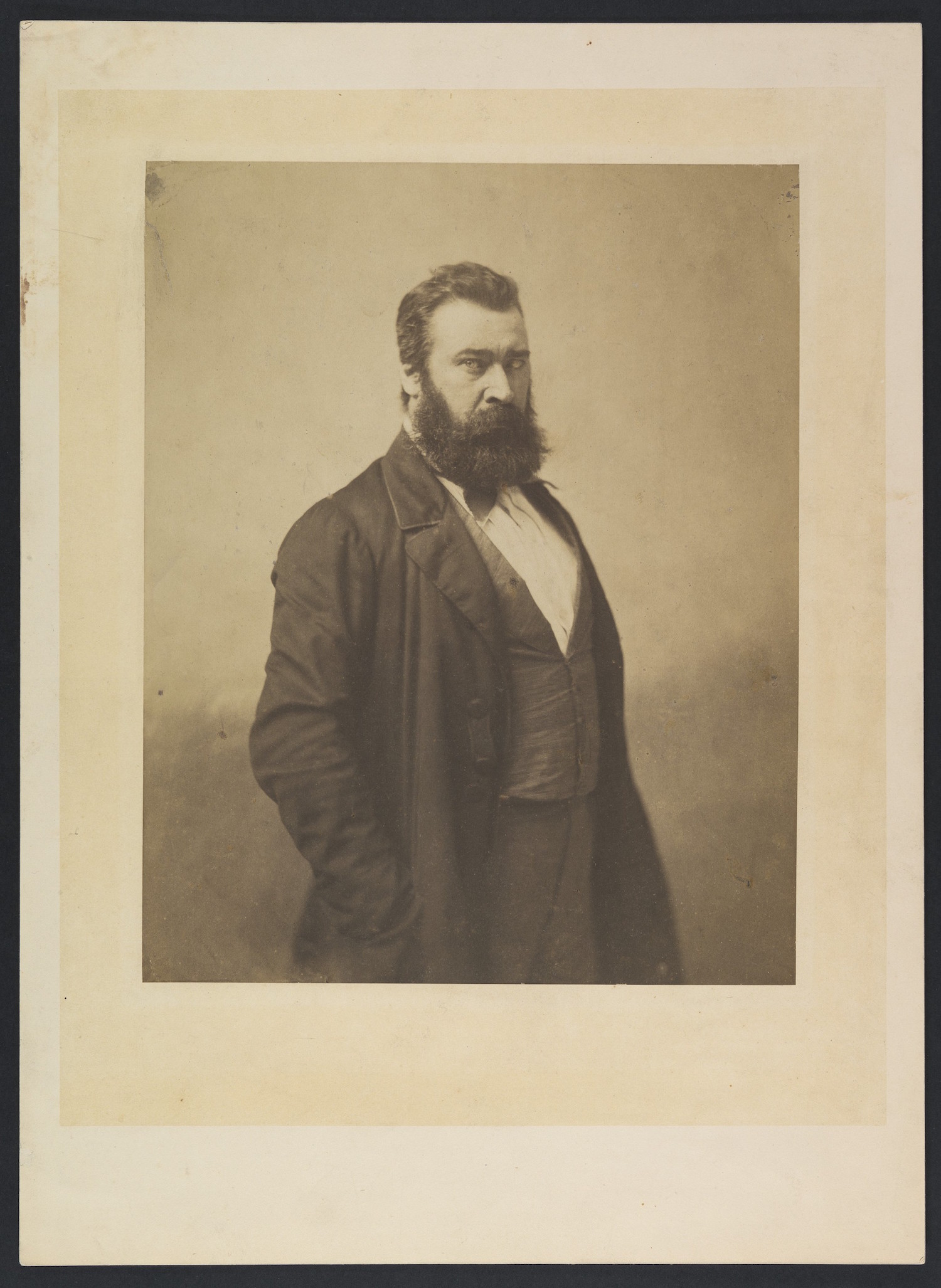

Jules (Emile Frederic) Massenet (1842-1912). French composer. From a photograph by Nadar, pseudonym of Gaspard-Felix Tournachon (1820-1910).

History

Nadar calls it “masculine infatuation pushed to the point of madness”. And who is madder than the man in pursuit of power?

Is it not the epitome of egotistical monomania, this hallucination that has no qualms about winning the approval of all hearts with the presentation of such mugs

But for him the epitome of this “insanity of male coquetry in its paroxysm” are clerics.

Never — ever! have I encountered in female creatures a similar science of arrangements and cosmetic strategy: disgusting…

How could I forget especially that one who came to me once in all the splendor borrowed from mother Jezebel, so outrageously rosy-cheeked that I could not resist the temptation to check it out?

Under the pretext of removing from his cheek an atom of soot, I take my handkerchief, I touch, and I find — carmine! My creature turned pale…

Does this vanity make the portrait photographer’s job an impossible one?

Every artistic or commercial establishment will be treated by its clients in the same way that it treats them, and vice versa… In truth, you would never be able to tame certain, often very charming monsters, whose naïvely ferocious egoism absolutely mocks everything that is not them.

If you are looking for a sign that your sitter is vain and self-aggrandizing, look at your watch. Are they late? If they are, consider yourself warned:

There are some who seem to derive a secret and intimate enjoyment from doing harm, for example, by disrupting the entire schedule of a workday with a delay, and turning all the appointments upside down, like a deck of cards.

Against these monsters, the profession itself will provide you with more than one sufficient riposte, if not to have everything turn out well, at least to neutralize their harmfulness. Hold on first, without wavering, to a rigorous punctuality, and remain ruthless to all latecomers, whatever the cost. What you might have lost on one side will soon be regained on the other.

So how do you do it? How do you succeed without burning bridges and irritating everyone you meet?

The whole question boils down for you into “doing well.” Always and still always look for the best, there and everywhere, and, preoccupied day and night with how to perfect your work, be stricter with yourself than with anybody else. Never let anything emerge from your studio that cannot defy the criticism of a rival.

To seek honor before profit is the surest means of finding profit with honor.

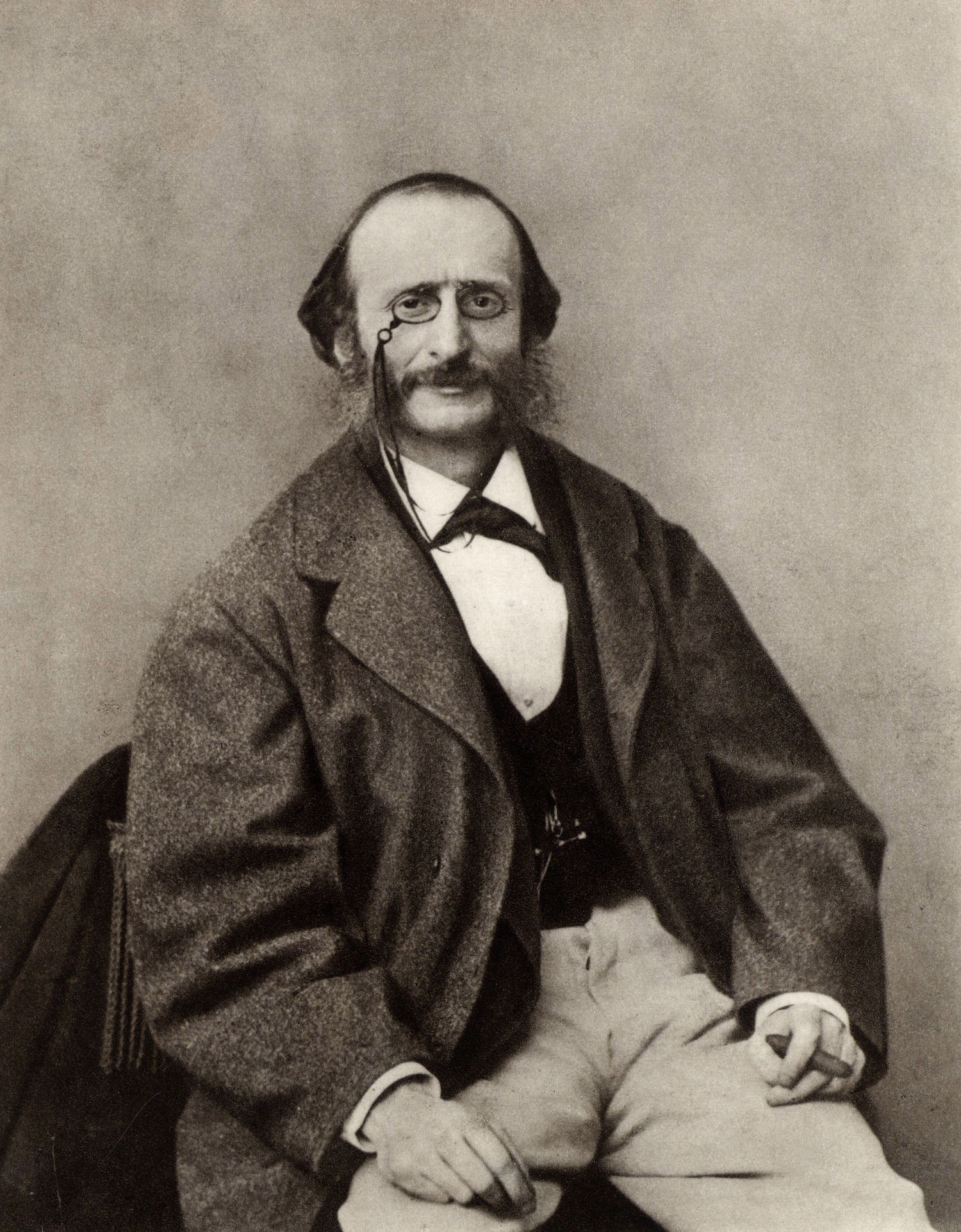

Gioachino (Antonio) Rossini (1792-1868) Italian composer. From a photograph by Nadar, pseudonymn of Gaspard-Felix Tournachon (1820-1910).

![[Self-Portrait]; Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon], French, 1820 - 1910; Paris, France, Europe; about 1855;](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Felix-Nadar-photographs-13.jpg)

[Self-Portrait]; Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon], French, 1820 – 1910; Paris, France, Europe; about 1855;

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.

![Nadar (French, Paris 1820–1910 Paris) [Self Portrait in American Indian Costume], 1863](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Felix-Nadar-photographs-24.jpg)