American architect, stage designer, mystic and writer Claude Fayette Bragdon (August 1, 1866 – 1946) set out to visualise the unseen fourth dimension – that’s three dimensions of space and one of time. As he noted: “We can never see, for instance four-dimensional pictures with our bodily eyes, but we can with our mental and inner eye.”

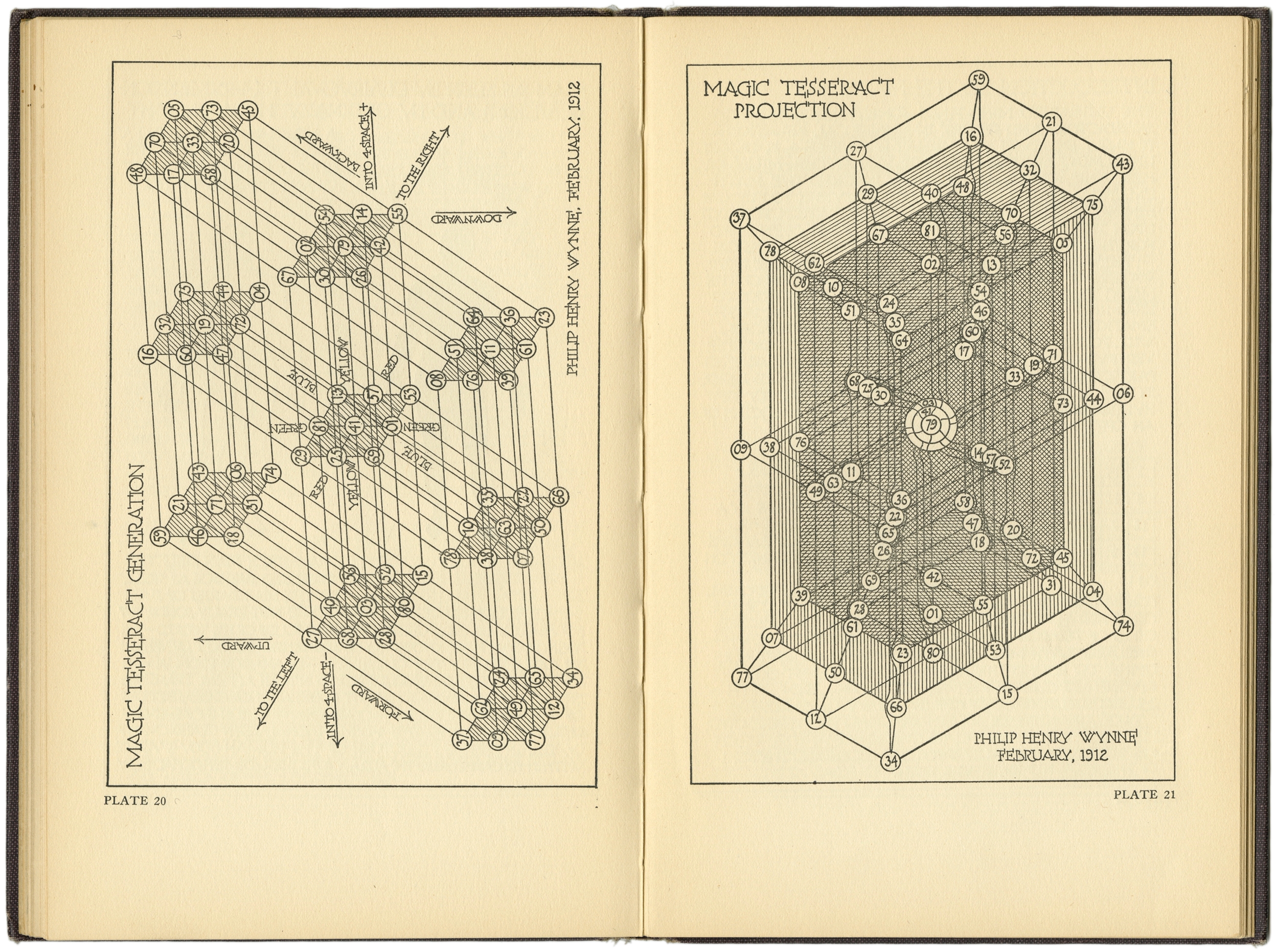

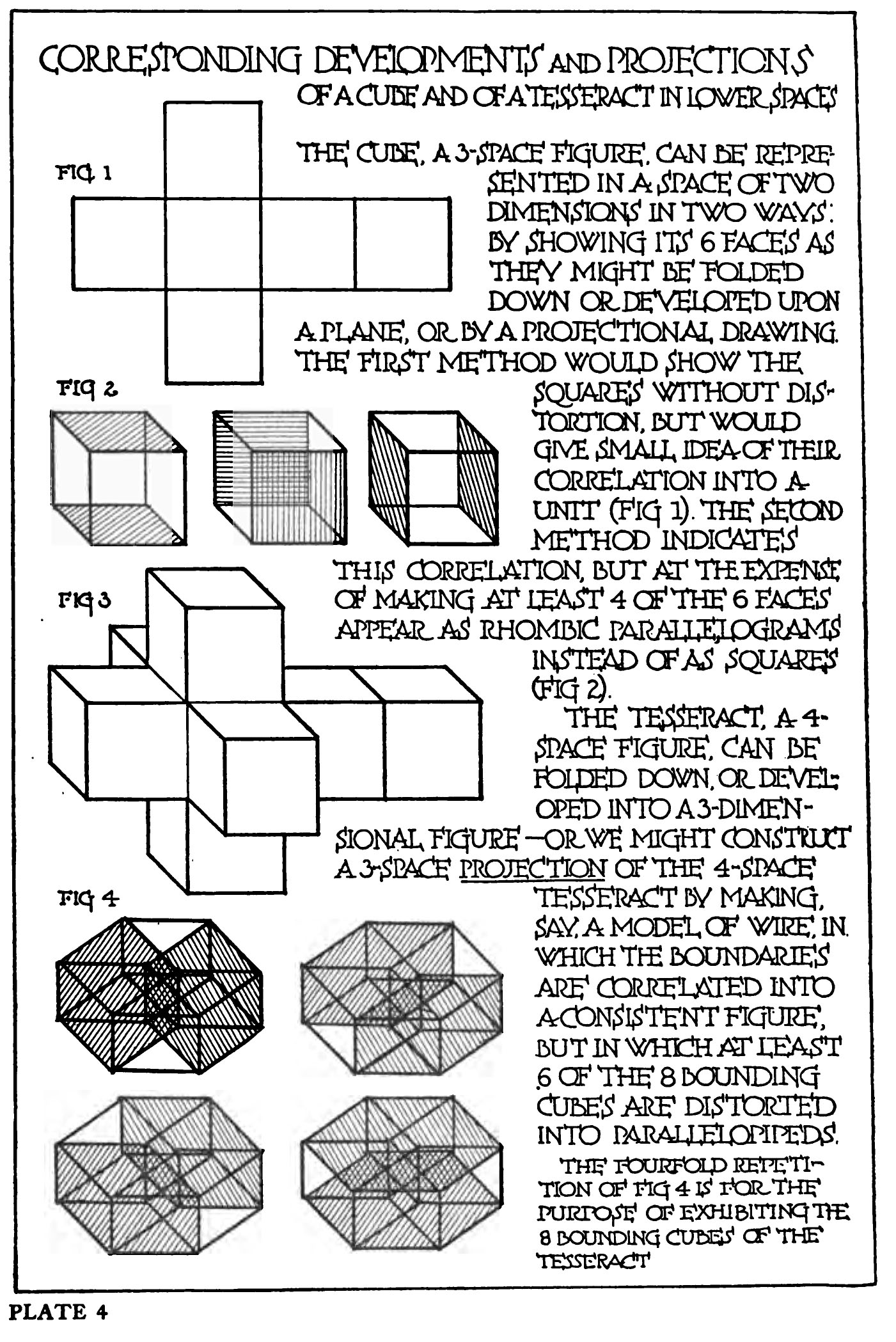

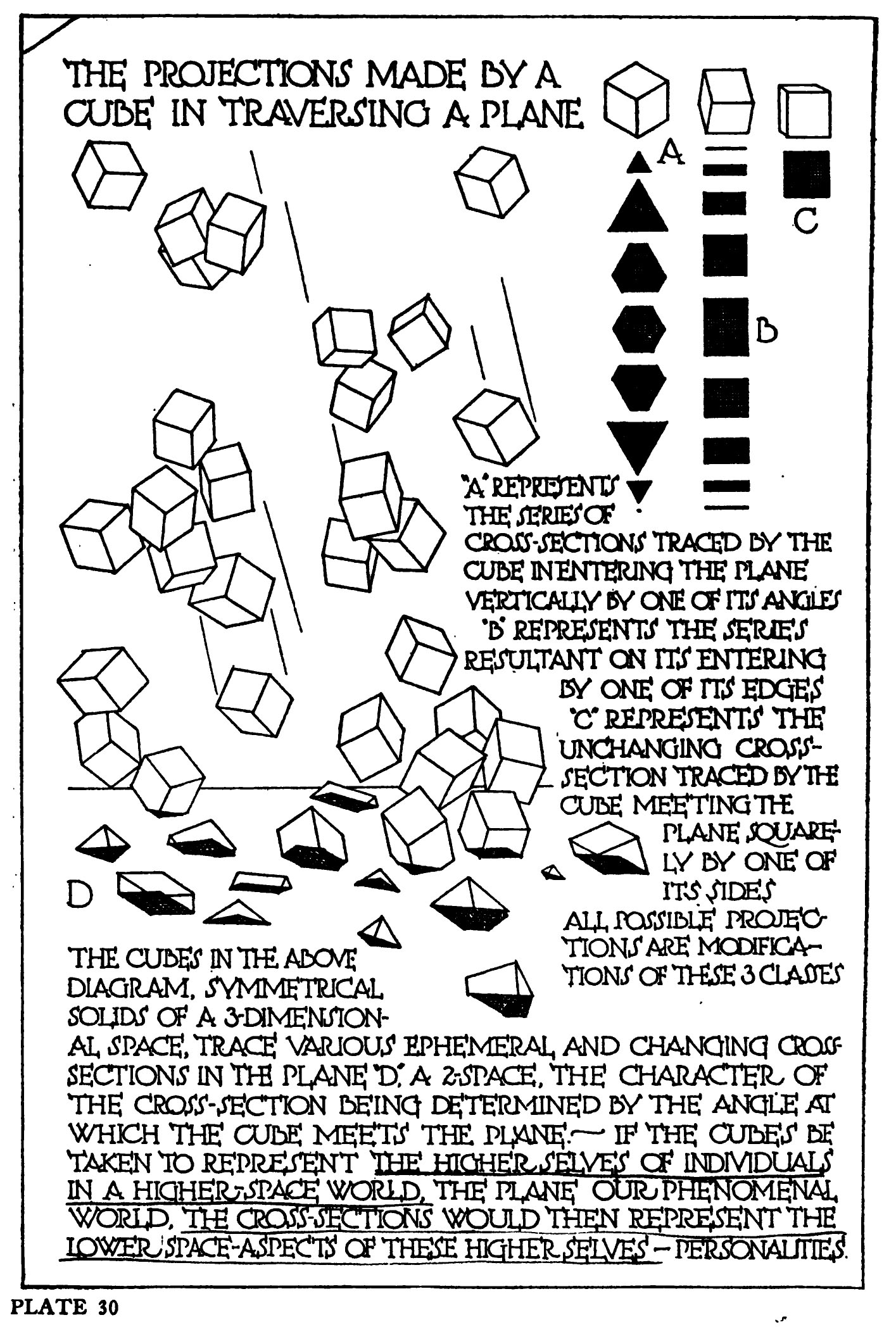

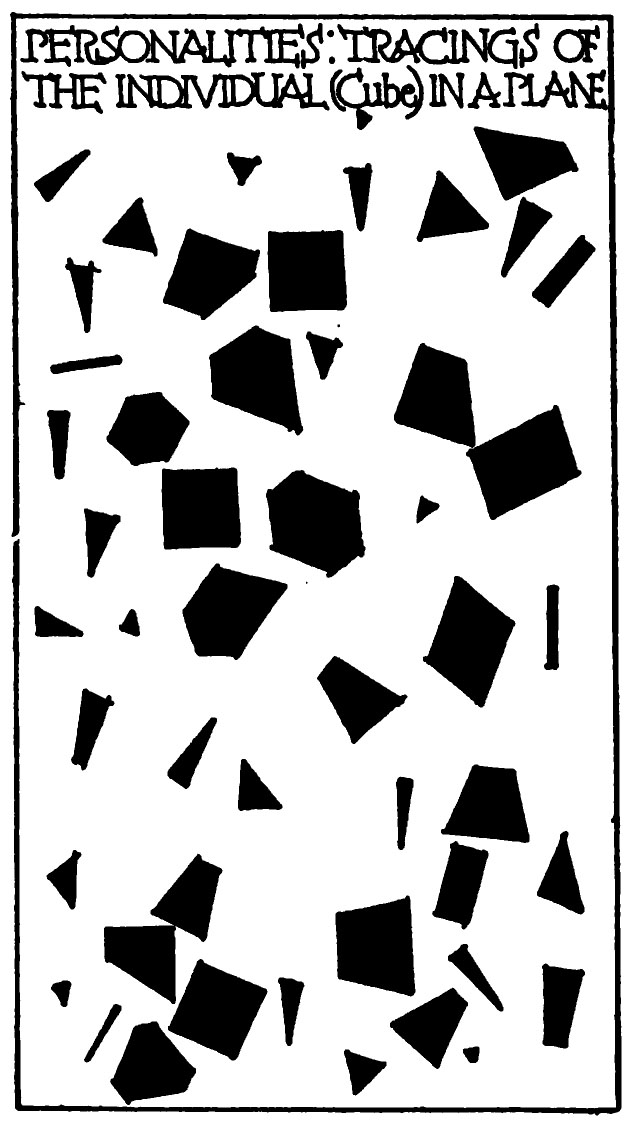

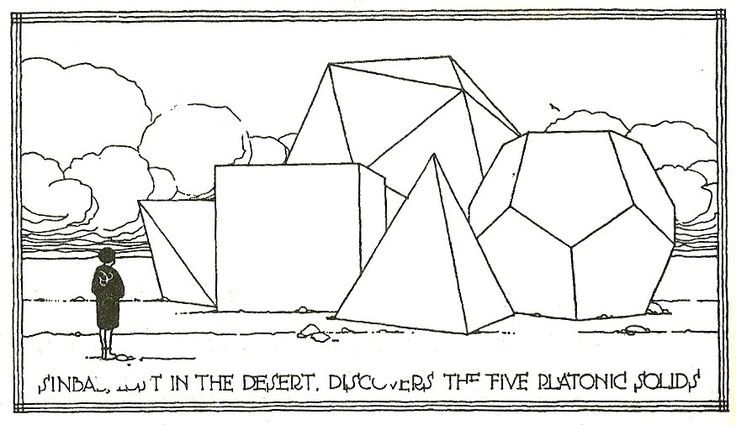

At this point, it’ useful to note what 4 dimensions means. One dimension is a single line connecting two points. To get to two dimensions, pull that line out and you add some width, making a space with four points, such as a square. Now push that shape back into a third dimension, giving it 8 points. The square has become a cube, a shape in three dimensions. Now push that cube into the fourth dimension, giving the square 16 points. Where is it? It’s in your mind’s eye. It’s not physical. We can only see three dimensions. If a creature from the fourth dimension were to pass through our line of vision, we’d only see slivers of it. You need to imagine. All you can do is try to represent the fourth dimension it 2 or 3 dimensions.

Much like Hilma af Klint did with her abstract pantings, Bragd0n had go at representing the invisible.

Based in Rochester, NY where he built his masterpiece, the New York Central Railroad Station in 1909, Bragdon’s design work and philosophy were influenced mainly by theosophy, a form of esoterism that preached the soul’s spiritual emancipation. Bragdon wrote architectural theory texts influenced by his spiritual beliefs and technological discoveries like x-rays.

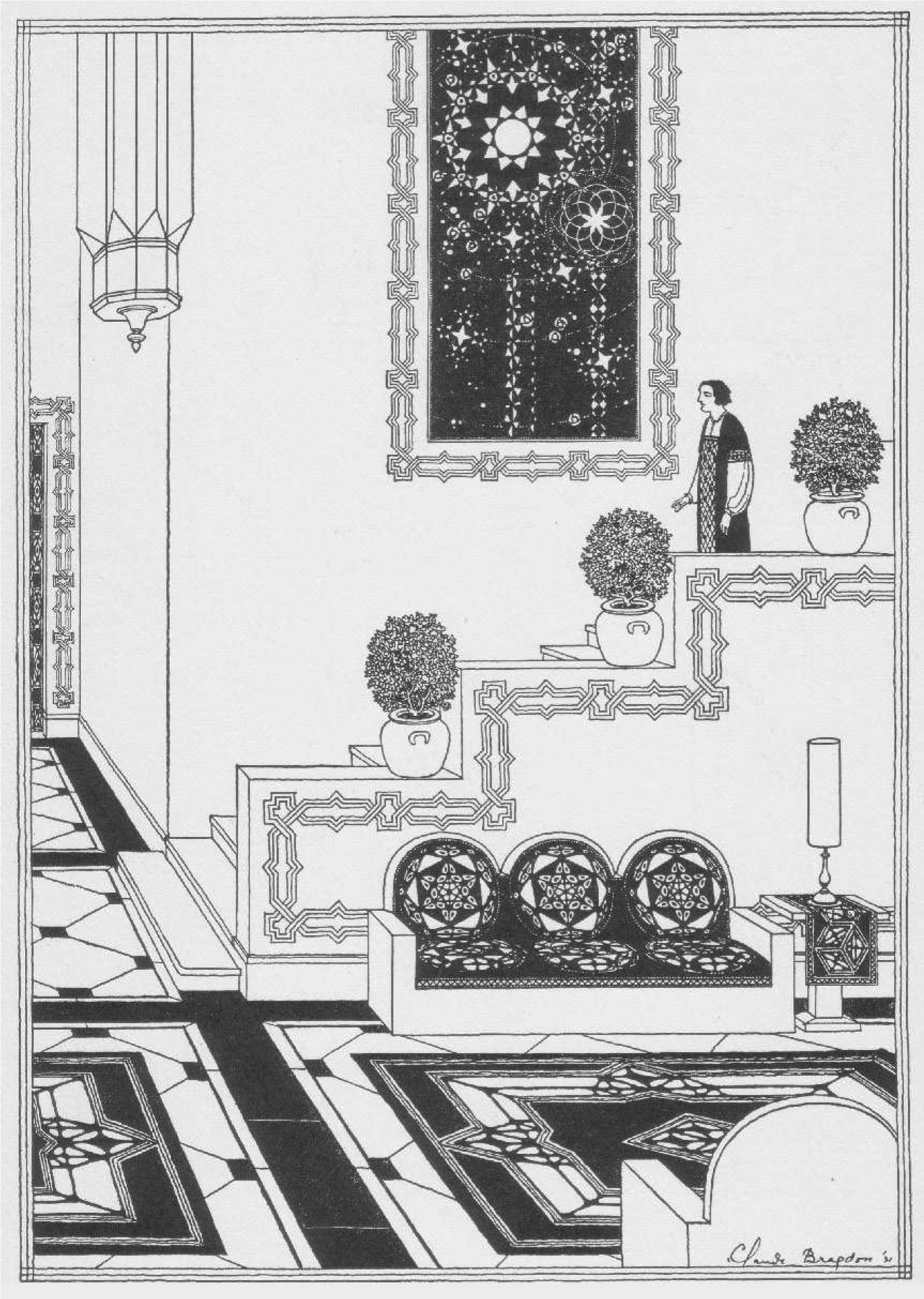

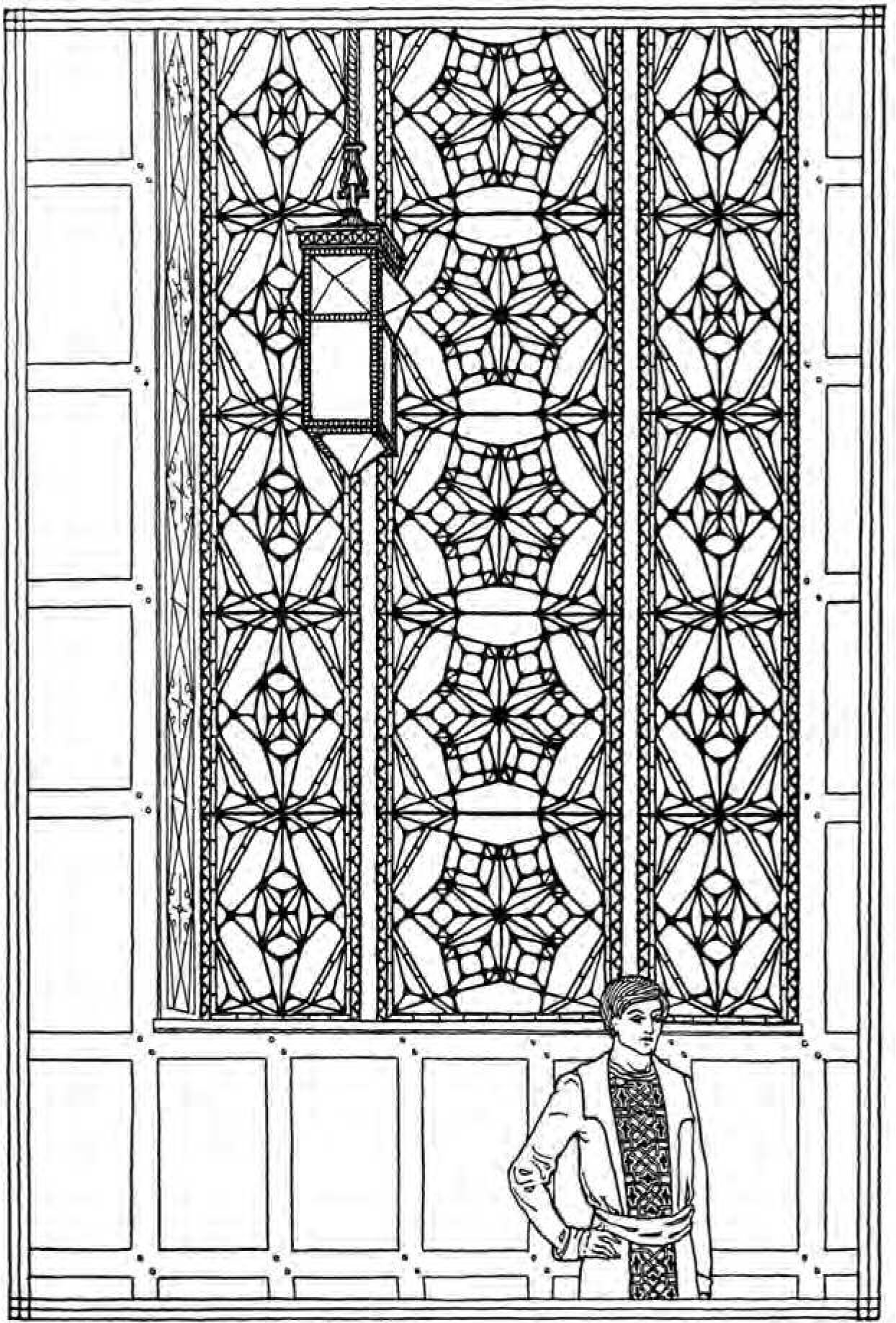

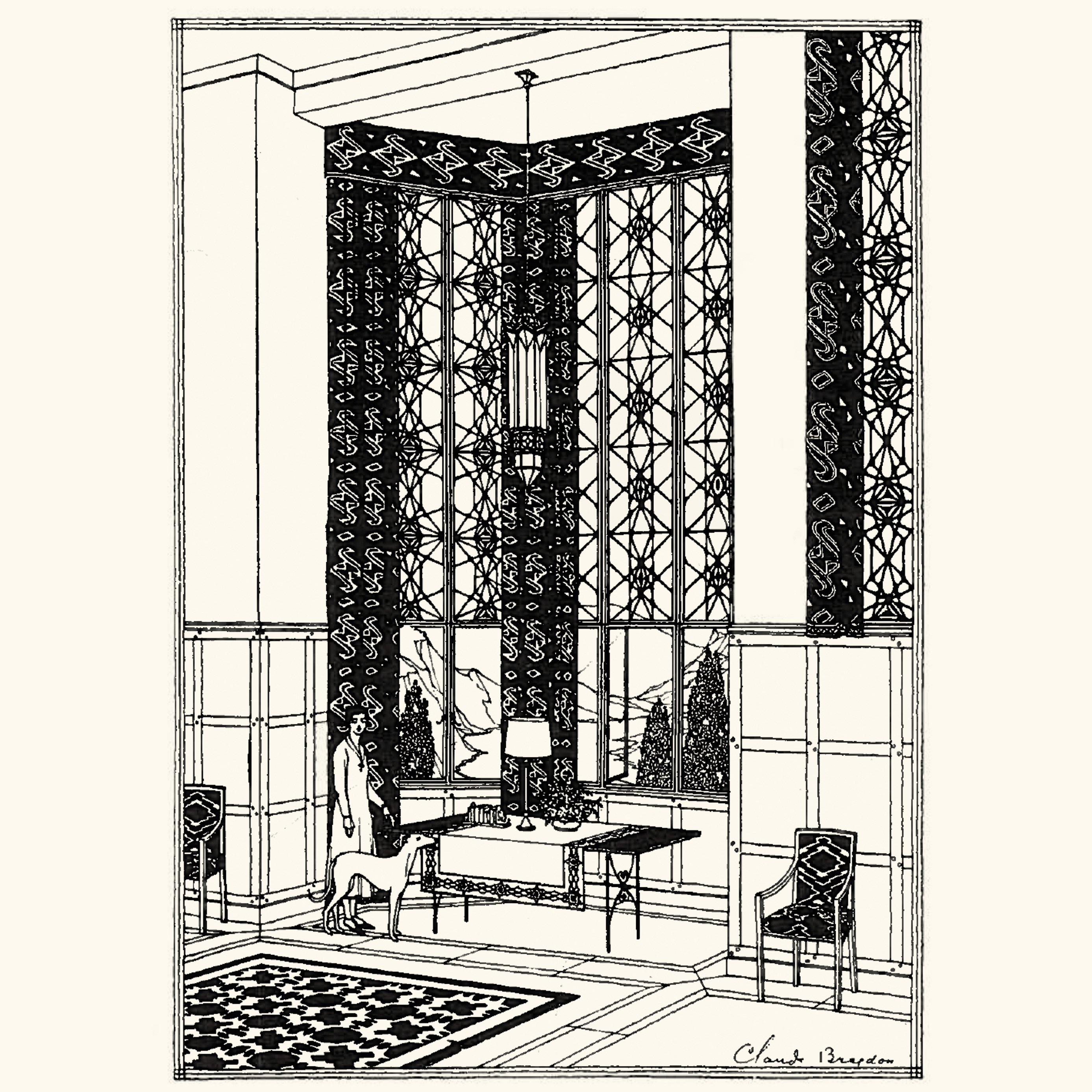

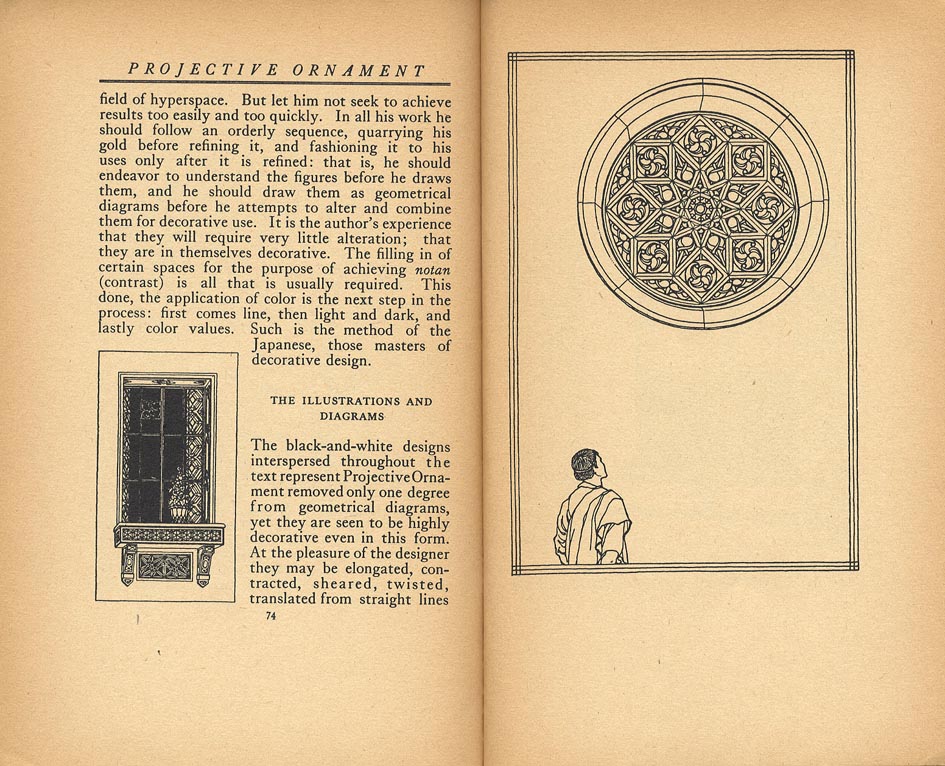

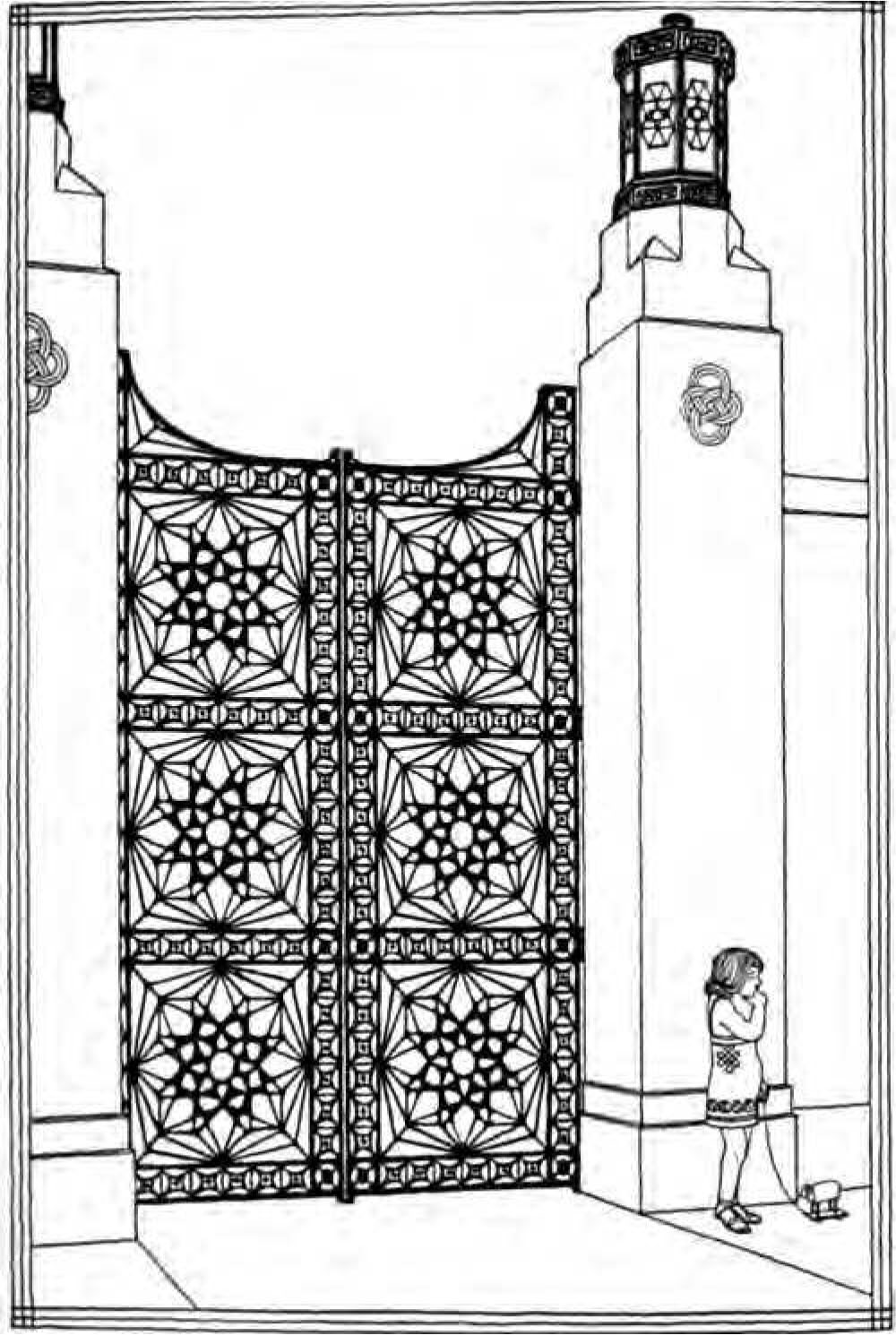

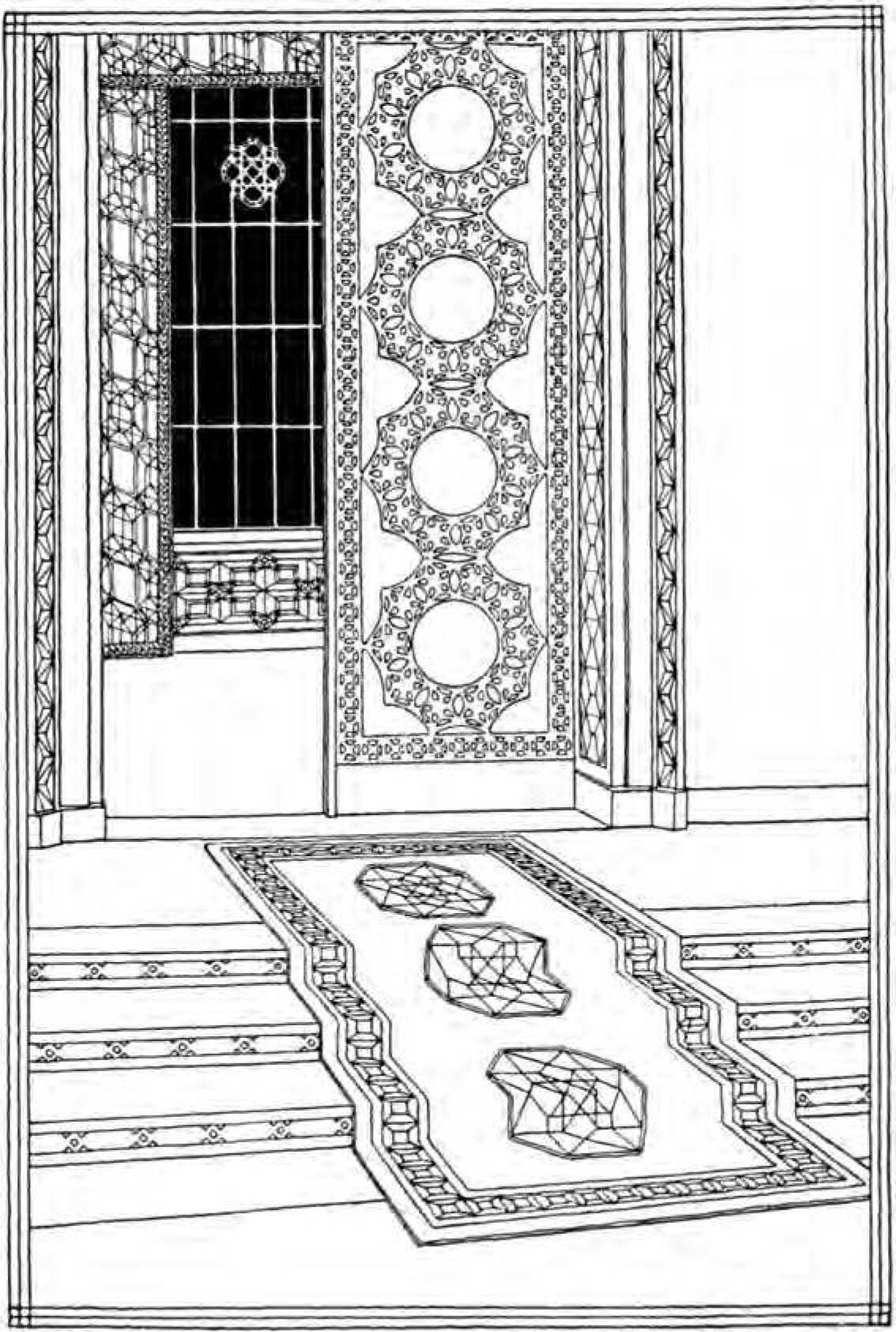

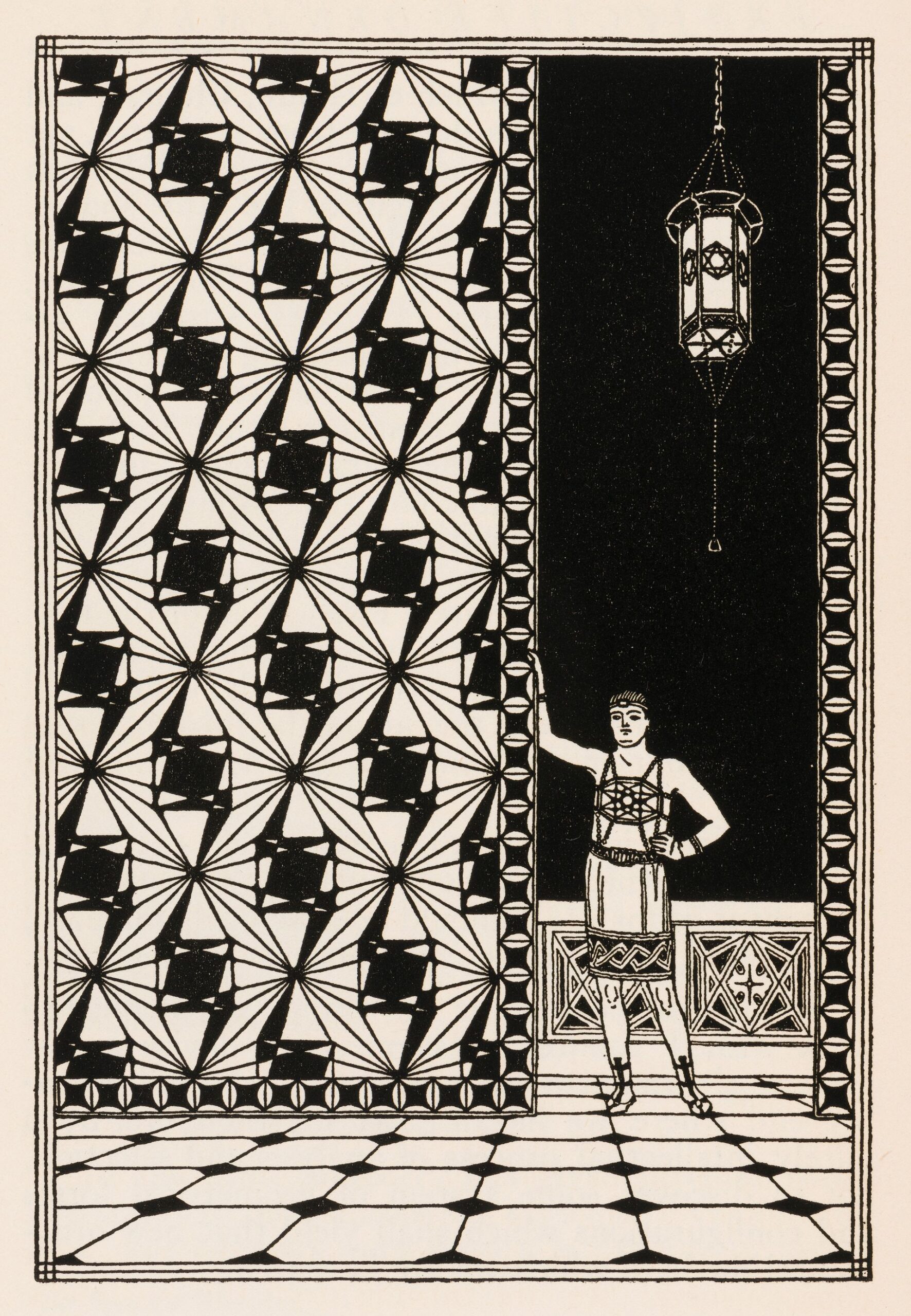

A skilled draftsman, Bragdon’s illustrations in pen and ink were inspired by Japanese drawings with an emphasis on a balanced composition and on the relevance and purity of lines. His texts focused on his idea of projective and fourth-dimension geometry as tools able to reach beyond the limits of the three-dimensional world and outside the mental constraints of human perception. Bragdon viewed geometry as symbolic and capable of revealing existential truths.

In A primer of higher space (1913) he attempted to provide a visual representation of the fourth dimension through two-dimensional projective drawings. In 1915, he published Projective Ornament, an essay focusing on ornament as a capital subject for the development of modern architecture, following Louis Sullivan’s research. Bragdon proposed an ornament derived from the two-dimensional projections of the fourth-dimensional space embracing human consciousness, psychological attributes and spiritual qualities, as well as its embodied presence.

A series of decorative patterns appear from folded-down axonometric representations of four-dimensional figures.

Following is a number of illustrations from these two books.

Bragdon approached geometry as a symbolic system capable of revealing existential truths. He combined mathematician Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann’s 1854 theory of n-dimensional space, which demonstrated that space could possess a potentially infinite number of dimensions, with a theosophical understanding of the fourth dimension as a transcendental space of human spiritual perfection.

In the early 1910s, Albert Einstein and Hermann Minkowski were already developing relativity theory and the concept of space-time, but their idea of the fourth dimension as time would not eclipse the concept of the fourth dimension as a higher spatial dimension until the early 1920s.

Meanwhile, Bragdon absorbed a Victorian tradition of moralizing mathematics that had invested with ethical and existential significance the idea of a physically real four-dimensional “hyperspace” beyond the range of normal sensory perception. The fourth dimension explained the mysteries of consciousness, spiritualist phenomena, and the afterlife, and it carried ethical imperatives to “cast out the self” in favor of altruistic devotion to humanity as a higher-dimensional whole –

– Crystal and Arabesque: Claude Bragdon, Ornament, and Modern Architecture by Jonathan Massey

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.