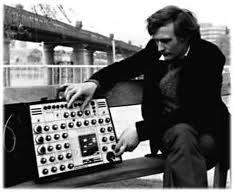

FLASHBACK to Delia Derbyshire (5 May 1937 – 3 July 2001).

Delia Derbyshire is the mathematics and music scholar most famous for creating the whirling intro to Dr Who. She was working at the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop in 1963 when she was given Ron Grainer’s score.

* She used concrete sources and sine- and square-wave oscillators, tuning the results, filtering and treating, cutting so that the joins were seamless, combining sound on individual tape recorders, re-recording the results, and repeating the process, over and over again.

On first hearing it Grainer asked her: “Did I really write this?” She replied: “Most of it.”

In 1970, the Sunday Mercury noted:

The [Dr Who] theme was based on a 16th-century composition by the astronomer Kepler, called “Harmony of the Spheres,” which was electronically treated to provide the science fiction sound associated with the programme.

She was working in a male world:

“After my degree I went to the careers office. I said I was interested in sound, music and acoustics, to which they recommended a career in either deaf aids or depth sounding. So I applied for a job at Decca Records. The boss was at Lords watching cricket the day I had my appointment, but his deputy told me they didn’t employ women in the recording studio.”

The BBC called:

“No doubt. I knew the BBC had a Research Department, and I knew that there was such a thing as the Radiophonic Workshop, that was credited with doing fantastic sounds for broadcast programs. People weren’t generally allowed to work at the Workshop for more than three months at a time. They thought it would send people crazy.

“I think it’d send me crazy.

“Well, it’s a beautiful way to be crazy, I can tell you.”

In 1964, she created the ethereal sounds for the BBC Third Programme 1964-01-05. The texts organised & voices recorded by Barry Bermange. Derbyshire was on the theta-wave sound collage & radiophonics.

YouTuber audiolemon notes:

While many were content to create mathematically structured enharmonic noise she looked for the ghost in the machine, creating haunting, off kilter and often sexually charged music. This track is from the 1969 The White Noise – Electric Storm LP. To me it sounds 30 years ahead of it’s time. I hope you like it.

What does Heaven sound like? In Amor Dei: A Vision of God (1964), we got a hint:

In 1997, she spoke to the BBC:

“I came from – what they’d like to call themselves – an upper working class Catholic background in Coventry. I was there in the blitz and it’s come to me, relatively recently, that my love for abstract sounds [came from] the air-raid sirens: that’s a sound you hear and you don’t know the source of as a young child… then the sound of the “all clear” – that was electronic music. I mentioned the Catholic bit: I was taken to benediction as a child and it was all in Latin -plain song hymns in an abstract language. After the worst blitz I was shifted to Preston, where my parents came from. It’s only today that I’ve realised that the sound of clogs on cobbles must have been such a big influence on me – that percussive sound of al the mill workers going to work at six o’clock in the morning.”

“Golly, I realised that… people that are just interested in self promotion and money are not my thing… you should see my last birthday card, a lovely one from America, with a whole shoal of fishes in silhouette with their mouths turned down and one fish swimming the other way with a smile on its face and printed on the card was “to an independent thinker”. (much laughter) I think that sums me up; I did rebel. I did a lot of things I was told not to do.”

She saw a relationship between maths and music:

People think that composers sit there with their pen over the manuscript paper, and God sends his inspiration down the top of the pen onto the paper. Well, in some cases it seems perhaps they did; perhaps Mozart. But in other cases one has to impose a discipline, and the discipline of number is an excellent discipline. The Fibonacci sequence people have been using for centuries.

Nature’s numbers; the number of leaves on a fern, the number of seeds on a sunflower head, and how they are arranged… this is the Fibonacci sequence, used in art and architecture and music. Although when you hear it in music, it is not recognised. Even George Gershwin used it in Porgy and Bess. Now who knows that?

The Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones paid her a visit. Delia was approached by Paul McCartney to arrange a backing track for The Beatles’ Yesterday. She told the magazine Boazine 7:

“He never came to the workshop. I always did work outside and he came to (Peter) Zinovieff’s studio and I played him some of my stuff – that’s all… but it was the phrase length he was interested in. I’ve always been non-conformist: I don’t like the 8 bar or the 12 bar standard thing. They’re all beautiful in their own way, but why not explore different phrase lengths? (Paul) never came to the workshop… Brian Jones did – golly! There we were with our hand tuned oscillators and he went into it with his frilly cuffs and things as though he could play it as a musical instrument! He died very young and I cried buckets. Pink Floyd (came to the workshop) and I took them down to Zinovieff’s place.”

He was Petr Zinovieff, creator of Electronic Music Studios Ltd (EMS) in London. He made the instruments, such as the VCS3 synthesizer used by Pink Floyd, David Bowie and Kraftwerk.

The Guardian visited Derbyshire in 1970:

Most interesting, of all the hardware in the studio, is a brand new EMS VC3 [sic], a voltage controlled studio in itself, housed in a casing about the size of a small desk. Trustingly propped for the moment on an ageing swivel chair, this treasure box is said to be the equivalent of a whole roomful of ordinary instruments and by the end of the year the workshop hopes to take delivery of a £6,000 version on a larger scale, and even cleverer.

Though we hear a lot of it, not always wittingly, I think many people are as puzzled as I was about the music and sounds manufactured in this workshop and others like it. What, exactly, does “electronic music” mean? How is it made? What is it used for?..

She sorted out for me, first of all, the basic definitions. Musique concrete has sound as its source, produced over a microphone and then deployed in different ways. Electronic music has as its source only electrical impulses…

“People seem to think I’m just working with funny noises, that it isn’t quite serious or something,” she told me. “I think a lot of people have a sort of block about electronic music, they think it must sound frightening and oppressive.”

And she worked with Yoko Ono.

“I did a film soundtrack for Yoko Ono. While she slept on my floor… It would be ’67 or ’68. It was about the same time that she met John Lennon. Because when we were having our or… oh… orgy on the carpet. We had a… golly, my goodness! So yes, she did her Bottoms film. And we did the soundtrack for the shorter film, which was the wrapping of the lions in Trafalgar Square, which was a happening. I also did the music for Peter Hall’s first feature film, Work is a Four Letter Word. I did the electronic part of the music… the bloopy bits when they’d taken the magic mushrooms.”

She spoke of “smelling the fibre-optic flowers”.

She created this dance track in the late Sixties. Paul Hartnoll, formerly of the dance group Orbital, opined: “That could be coming out next week on [left-field dance label] Warp Records. It’s incredible when you think when it comes from. Timeless, really. It could be now as much as then.”

Among her outstanding television work, one of her favourites was composed for a documentary for The World About Us on the Tuareg people of the Sahara desert. It still haunts me. She used her own voice for the sound of the hooves, cut up into an obbligato rhythm, and she added a thin, high electronic sound using virtually all the filters and oscillators in the workshop.

“My most beautiful sound at the time was a tatty green BBC lampshade,” she recalled. “It was the wrong colour, but it had a beautiful ringing sound to it. I hit the lampshade, recorded that, faded it up into the ringing part without the percussive start.

“I analysed the sound into all of its partials and frequencies, and took the 12 strongest, and reconstructed the sound on the workshop’s famous 12 oscillators to give a whooshing sound. So the camels rode off into the sunset with my voice in their hooves and a green lampshade on their backs.”

More here. And buy her wonderful sounds here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.