“At 110, everything I create; a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before. To all of you who are going to live as long as I do, I promise to keep my word. I am writing this in my old age. I used to call myself Hokusai, but today I sign my self ‘The Old Man Mad About Drawing.”

― Hokusai Katsushika, the ‘Old Man Crazy To Paint’

Katsushika Hokusai’s (葛飾 北斎, c. 31 October 1760 – 10 May 1849) Under The Great Wave off Kanagawa is familiar enough to be known as simply The Great Wave. The woodblock print was created in 1831 as part of the Japanese ukiyo-e artist’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, a series printed in thousands of editions before the woodblock wore out and could no longer be used. (After their publication, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji was such a hit that Hokusai added another ten images, resulting in 46 prints in the series.)

Capucine Korenberg, a scientist at The British Museum is on a mission to create a timeline of the print’s many versions. In this video, Korenberg looks at the three editions held in The British Museum’s collection. To date, there are 113 known versions. But which was the first, and what did the Great Wave look like first time around?

She hunts for small variants between prints to try and work out which line faded or thinned first. She has narrowed the change down to eight stages.

An Illustrated History of Katsushika Hokusai’s Great Wave

Hokusai, a popular artist of the ukiyo-e, or “floating world” school of Japanese art, made many images of waves before his most famous artwork. In a colophon to his series One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku hyakkei), he wrote:

From the age of six I had a penchant for copying the form of things, and from about fifty, my pictures were frequently published; but until the age of seventy, nothing that I drew was worthy of notice. At seventy-three years, I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects, and fish. Thus, when I reach eighty years, I hope to have made increasing progress, and at ninety to see further into the underlying principles of things, so that at one hundred years I will have achieved a divine state in my art, and at one hundred and ten, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive. Those of you who live long enough, bear witness that these words of mine prove not false.

In 1797,Hokusai made what could be considered his first wave print, Spring at Enoshima (Enoshima shunbô):

But why waves? In the early 19th century Japan had taken no part in international discourse for two centuries and remained apart from the world, allowing in only Chinese and Dutch merchants, and not allowing Japanese to leave. In Stephen Sondheim’s Pacific Overtures (1976), the composer tells us the mood in Japan in 1853, before its ports were opened by force and the world moved in:

“In the middle of the world we float,

In the middle of the sea.

The realities remain remote

In the middle of the sea.

Kings are burning somewhere,

Wheels are turning somewhere,

Trains are being run,

Wars are being won,

Things are being done

Somewhere out there, not here.

Here we paint screens.

Yes… the arrangement of the screens.”

So there was Japan in a sea of calm. Then the waters broke and the wave of change soars and threatens to swamp the county, like the people in the three boats facing the oncoming waves as Mount Fuji, that central symbol of Japanese being and identity, appears diminished in the background. (In Buddhist and Daoist tradition, Mount Fuji was believed to hold the secret of immortality.)

Christine Guth has studied Hokusai’s work in depth, especially ‘The Great Wave’, notes:

“It was produced at a time when the Japanese were beginning to become concerned about foreign incursions. So this great wave seemed, on the one hand, to be a kind of a symbolic barrier for the protection of Japan, but at the same time it also suggested the potential for Japanese to travel abroad, for ideas to move, for things to move back and forth. I think it was very closely tied to the beginnings of the opening of Japan, if you will.”

View of Honmoku off Kanagawa (Kanagawa-oki Honmoku no zu), 1803:

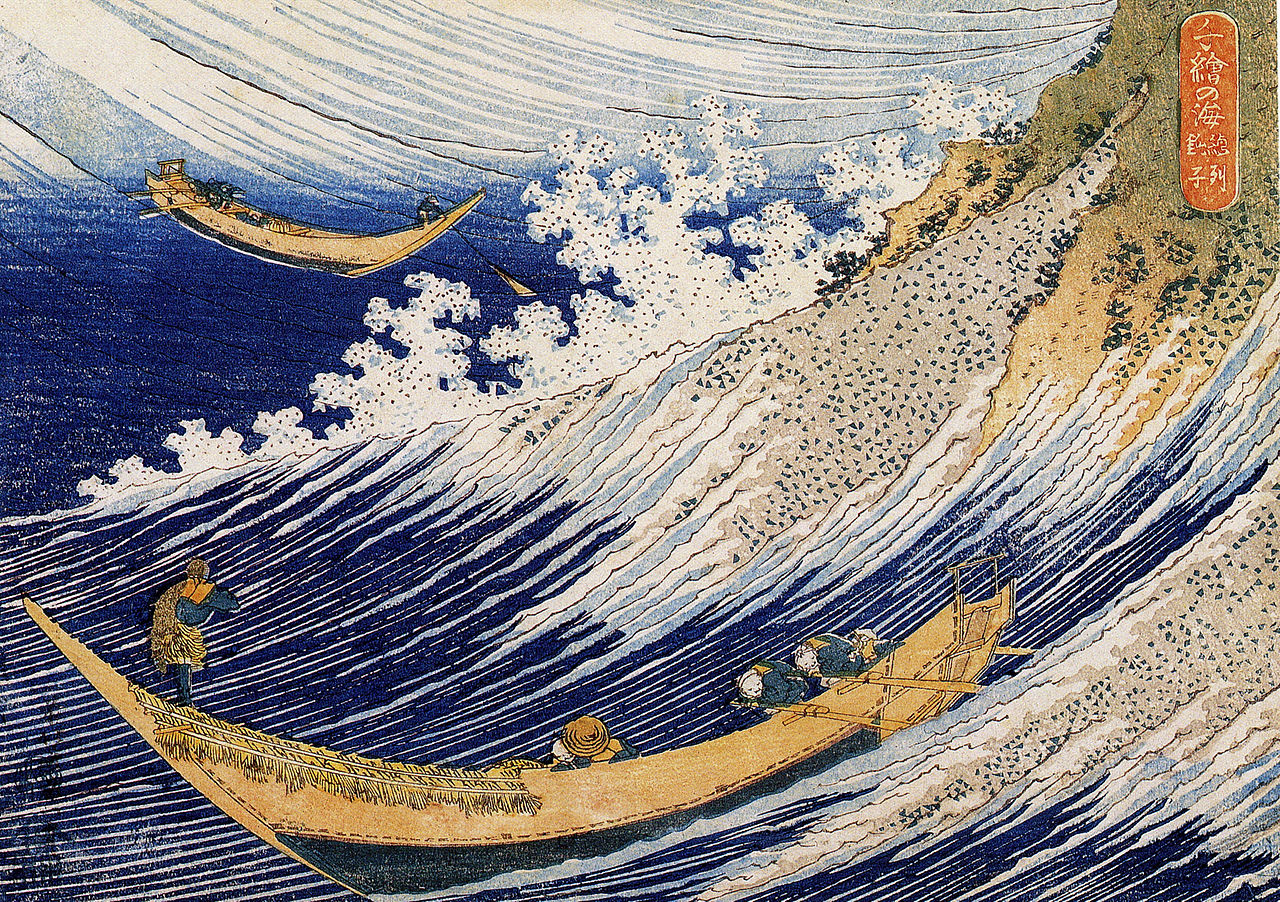

In 1805, he created Express Delivery Boats Rowing through Waves (Oshiokuri hatô tsûsen no zu), from an untitled series of landscapes in the Western style.

1833. ‘Chôshi in Shimôsa Province’

Fuji at Sea (Kaijo no Fuji), circa 1834 (and in colour):

Kajikazawa in the province of Kai (1829-1833):

More Japanese prints are at the Flashback Shop.

Via: Daily Art Magazine, This Is Colossal.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.