During World War 2, French-Jewish artist Claude Cahun and her life partner and step-sister, the fashion designer and illustrator Marcel Moore, lived on the island of Jersey, a self-governing Crown Dependency off the coast of Normandy in the English Channel, or La Manche, if you’re French.

Jersey is a small, rather odd part or the British Isles. The author Victor Hugo described the Channel Islands as “bits of France that fell into the sea and were picked up by England”.

Having taken over France, the Germans used the island as a training ground for new recruits. Jersey was occupied by Germany from 1 July 1940 until 9 May 1945, when Germany surrendered.

The Germans constructed many fortifications on the island using Soviet slave labour. The Channel Islands were one of the last places in Europe to be liberated. And for most of the occupation, Cahun and Moore waged a secret campaign of disinformation and morale-destruction, using, as Hugh Ryan notes, “a weapon the Nazis never expected: Surrealism.”

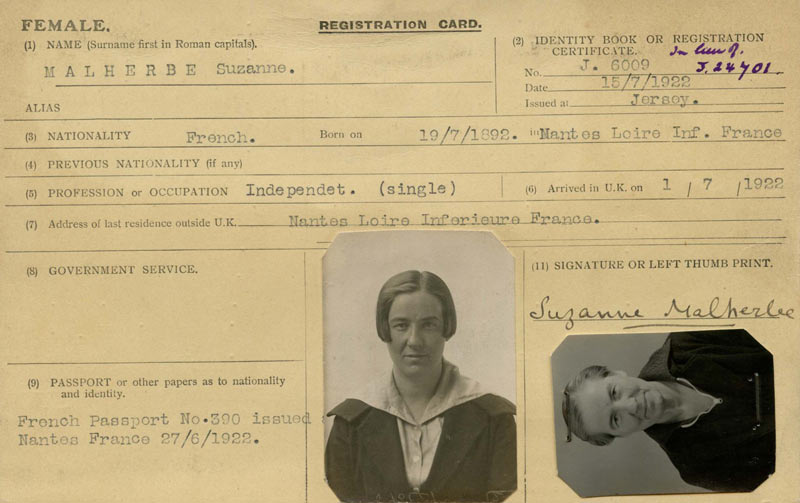

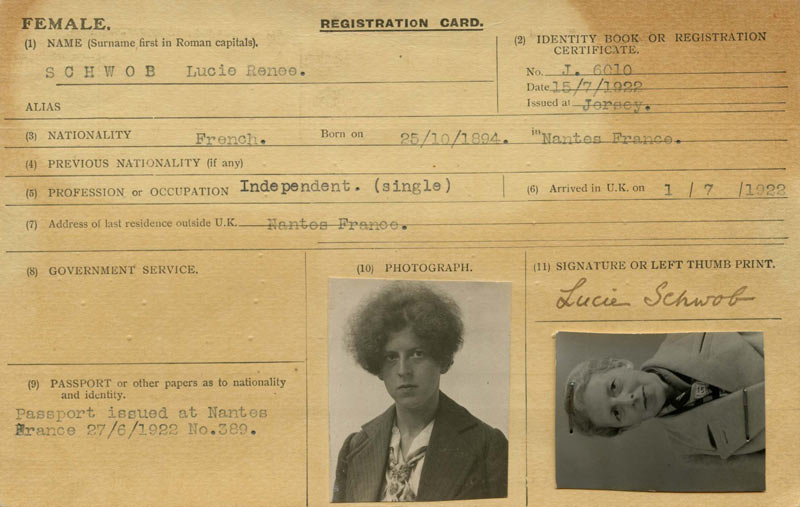

Claude Cahun’s Jersey ID card under German occupation

As German soldiers walked along the streets and attended meetings and funerals, the pair would slip anti-fascist poems into their pockets. They’d screw up notes and toss them through open car windows.

They lived in La Rocquaise, a granite house close to St Brelade’s Parish Church, overlooking a bay. Both women had been born in Nantes and naturally spoke French. Cahun, who had spent a time at a school in Surrey, England, also spoke English. Even more helpfully, Moore was fluent in German. The languages enabled them to write letters pretending to be from disgruntled soldiers urging the new recruits to desert. Many of these messages were created under the German pseudonym Der Soldat Ohne Namen (The Soldier With No Name), to deceive Germans that there was a conspiracy among their ranks. Notes advised the occupying forces to mutiny and shoot their officers.

Cahun and Moore stole Nazi propaganda posters and cut them up into resistance flyers, which they hid inside cigarette boxes and left around the island for soldiers to find. On one occasion, they hung a banner in a church, which stated: “Jesus is great, but Hitler is greater – because Jesus died for people, but people die for Hitler.”

So prolific was their output that Germans believed there was a thriving resistance on the island and rebels among the troops.

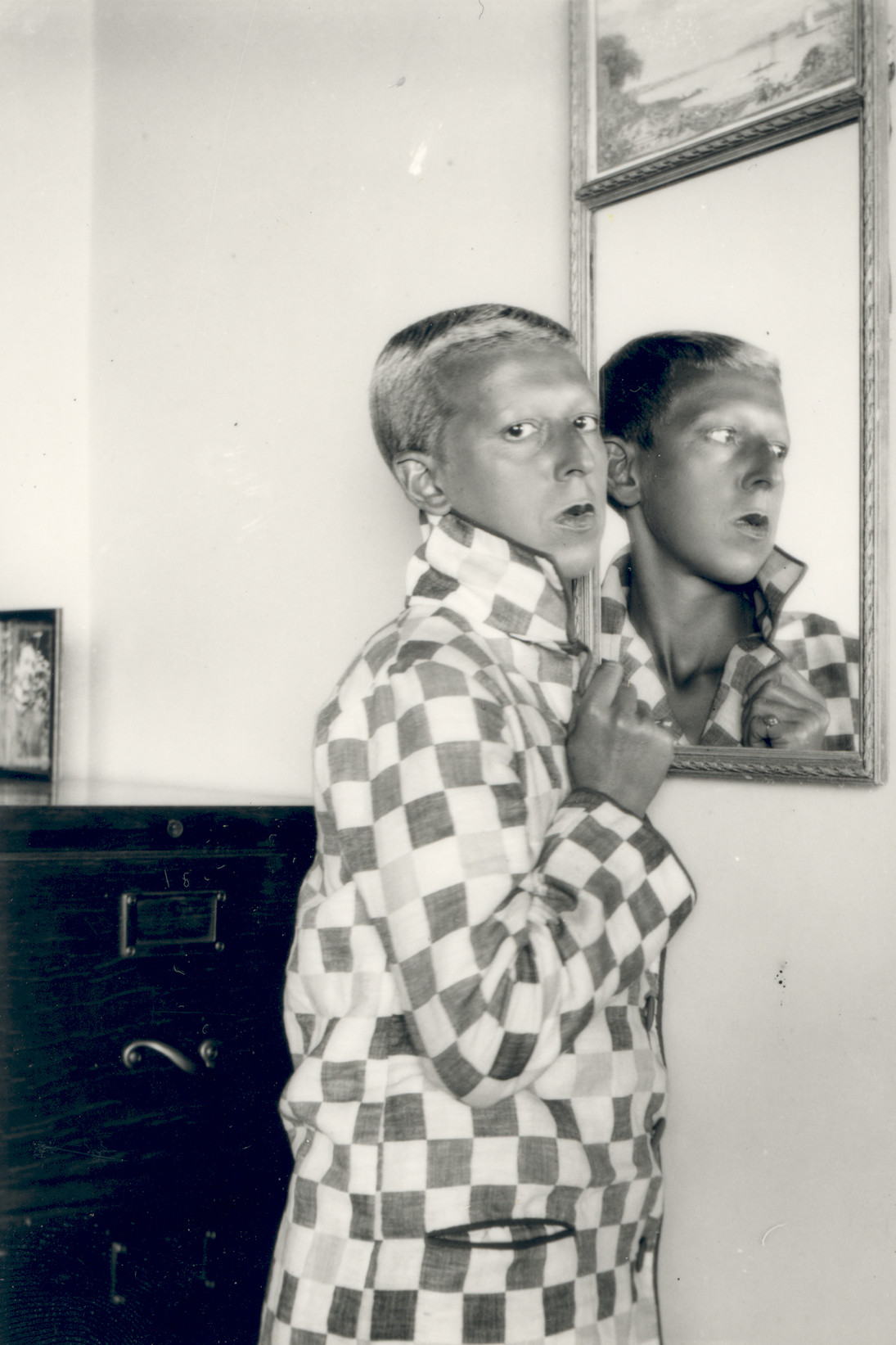

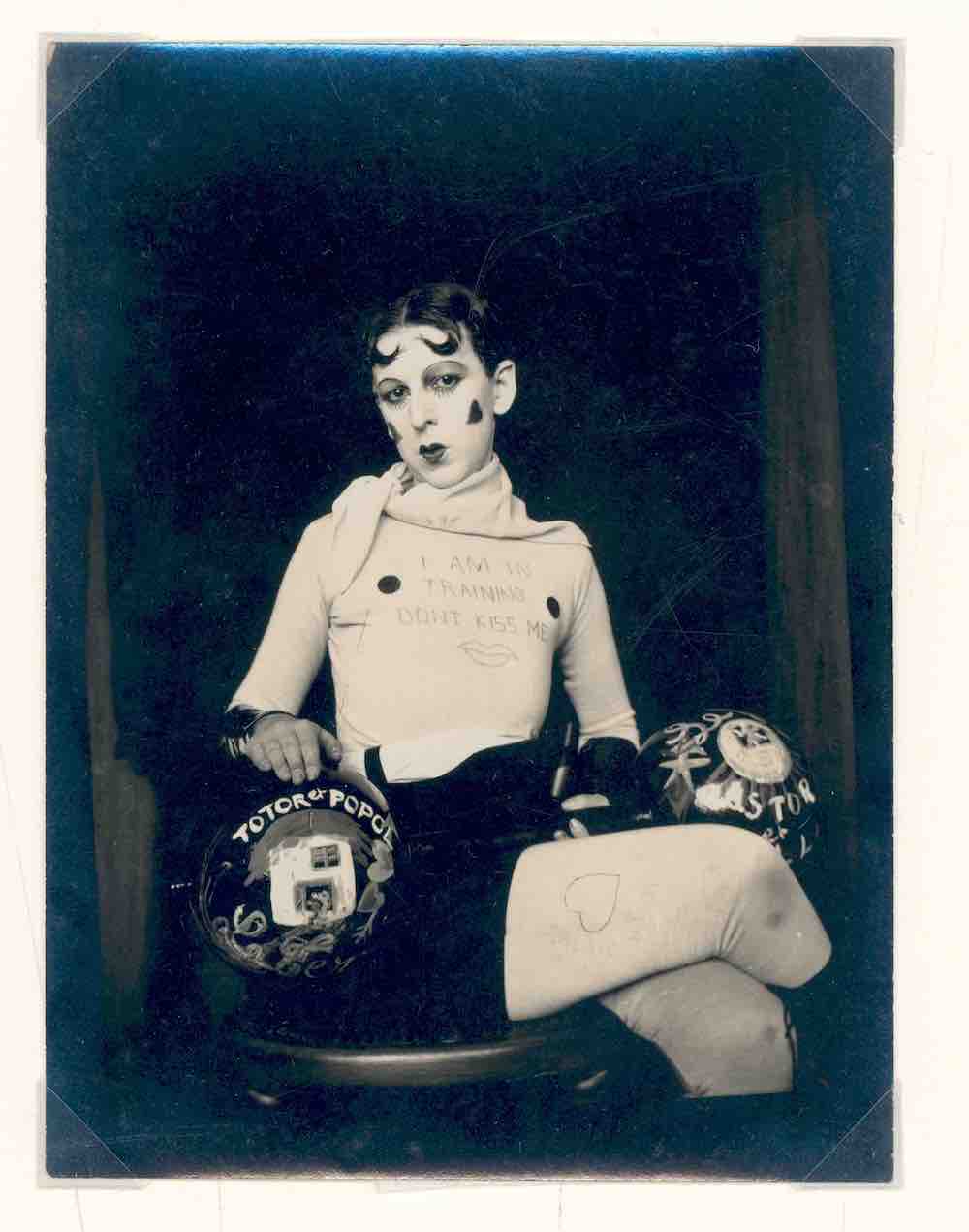

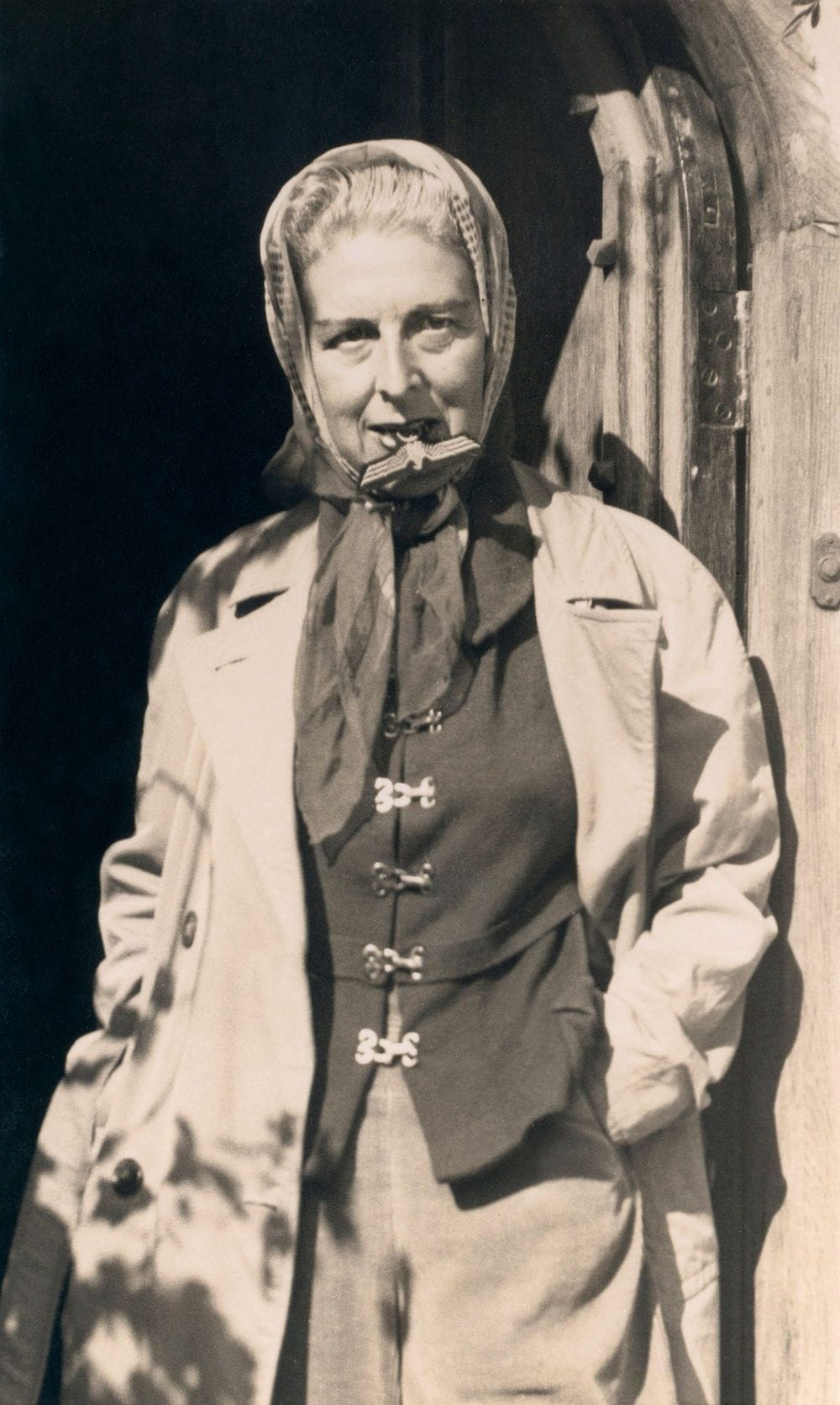

The pair relished the anti-German campaign. Through her work, Cahun challenged notions of identity and gender. Her androgynous self-portraits brought to life a range of characters. At one moment, she’s a circus strongman, holding weights. In another, she’s a lady of the manor swathed in velvet. In wartime, she and Moore played the roles of two doddery old dears, adherents to the rule that if you really want to be invisible, be old and grey. Like Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, no-one notices the spinster.

The women aspired to a new social order, free of the social and sexual conventions of the society they’d grown up in. Cahun (25 October 1894 – 8 December 1954) was born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob. Moore (19 July 1892 – 19 February 1972) was born Suzanne Alberte Malherbe. Names and roles were not fixed at birth. “Masculine? Feminine?” Cahun wrote in her book Aveux non Avenus. “It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” Life was what you made it. Self was varied and fluid. “My role,” Cahun wrote in an essay published after her death, “was to embody my own revolt and to accept, at the proper moment, my destiny, whatever it may be.” The pair thrived on ambiguity. And before the artists who explored gender and sexuality with courage, talent and wit was the epitome of totalitarianism.

Their subterfuge came to an end in 1944, when they were arrested and sentenced to death for “undermining the morale” of the German forces. Rumour has it that the woman who supplied the tissue paper on which they wrote their notes grassed them to the Germans.

At their trial, Cahun said to the German judge that the Germans would have to shoot her twice, as she was not only a Resister but a Jew.

But before they could be murdered, the island was liberated. The two remained in Jersey for another decade, until Cahun died in 1954, never having fully recovered from the year they spent in a German prison. Having lost her best friend, lover and collaborator, Moore relocated to a smaller home, and committed suicide in 1972. She is buried alongside Cahun in Jersey. The Germans destroyed much of their artwork on account of its “degenerative” qualities. Cahun’s work was largely unknown until its rediscovery in the 1990s.

Self portrait. May 8, 1945. Cahun poses in ‘nice old dear’ disguise with a Nazi emblem between her teeth

The sisters’ gravestone at St Brelade Church cemetery

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.