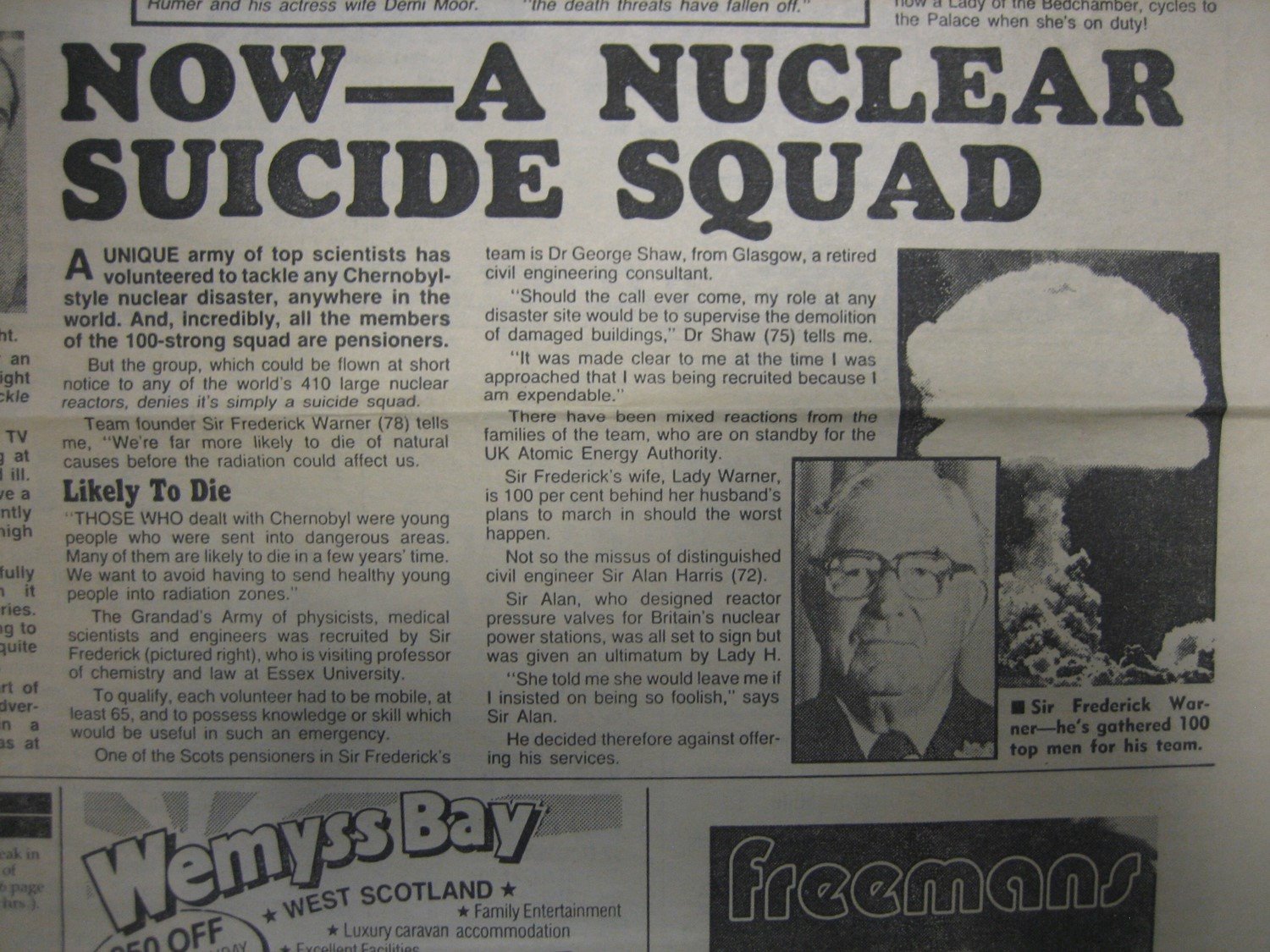

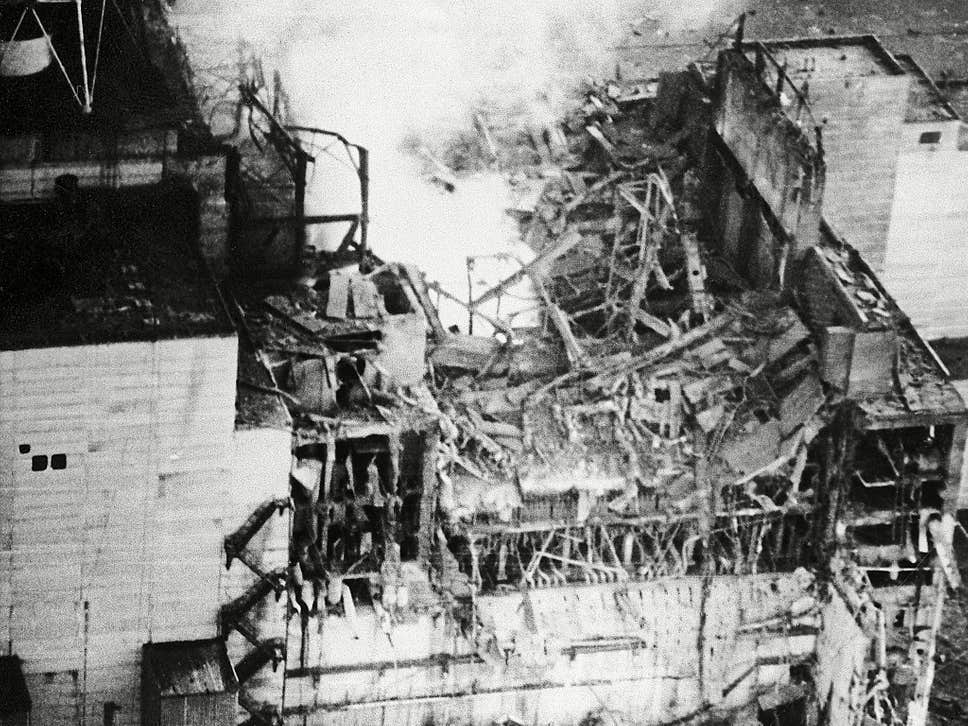

Professor Sir Frederick Warner (born 31 March 1910; died 3 July 2010) was a leading authority on chemical risk management and nuclear safety. He led the first international team into the ruins of the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Soviet Ukraine. On April 26 1986, accidental explosions at Reactor 4 threw up a cloud of radiation stretching from Ukraine to Scandinavia. The disaster killed many and damaged thousands of lives. The USSR’s response was deeply flawed. Thousands of ill-equipped workers were sent in to fight the fires and bury the reactor. They were exposed to lethal levels of radiation. Contaminated farm produce was harvested, repackaged and sold as fit for human consumption. Warner wanted the UK to be better prepared. He wanted to set up a ‘suicide squad’ of skilled volunteers to enter the danger zone and save the day.

Disturbed by the deaths of scores of Soviet soldiers and firefighters (so-called liquidators) exposed to high doses of radiation during the initial containment operation, Warner created Volunteers for Ionising Radiation, a squad of over-65s who would be available to help during any future such emergencies. He reasoned that engineers and scientists over 65 would tolerate exposure better than those who were younger and would have fewer concerns over possible genetic effects. In the event of nuclear catastrophe, ‘The Expendables’ would spring into action, ready to enter accident zones where “levels of radioactivity soared far above the limits of radiation exposure set for employees”.

It had been very different in the old USSR. It took a full week after the accident at Chernobyl for Soviet officials to announce the evacuation of anyone living within 30-km of the plant.

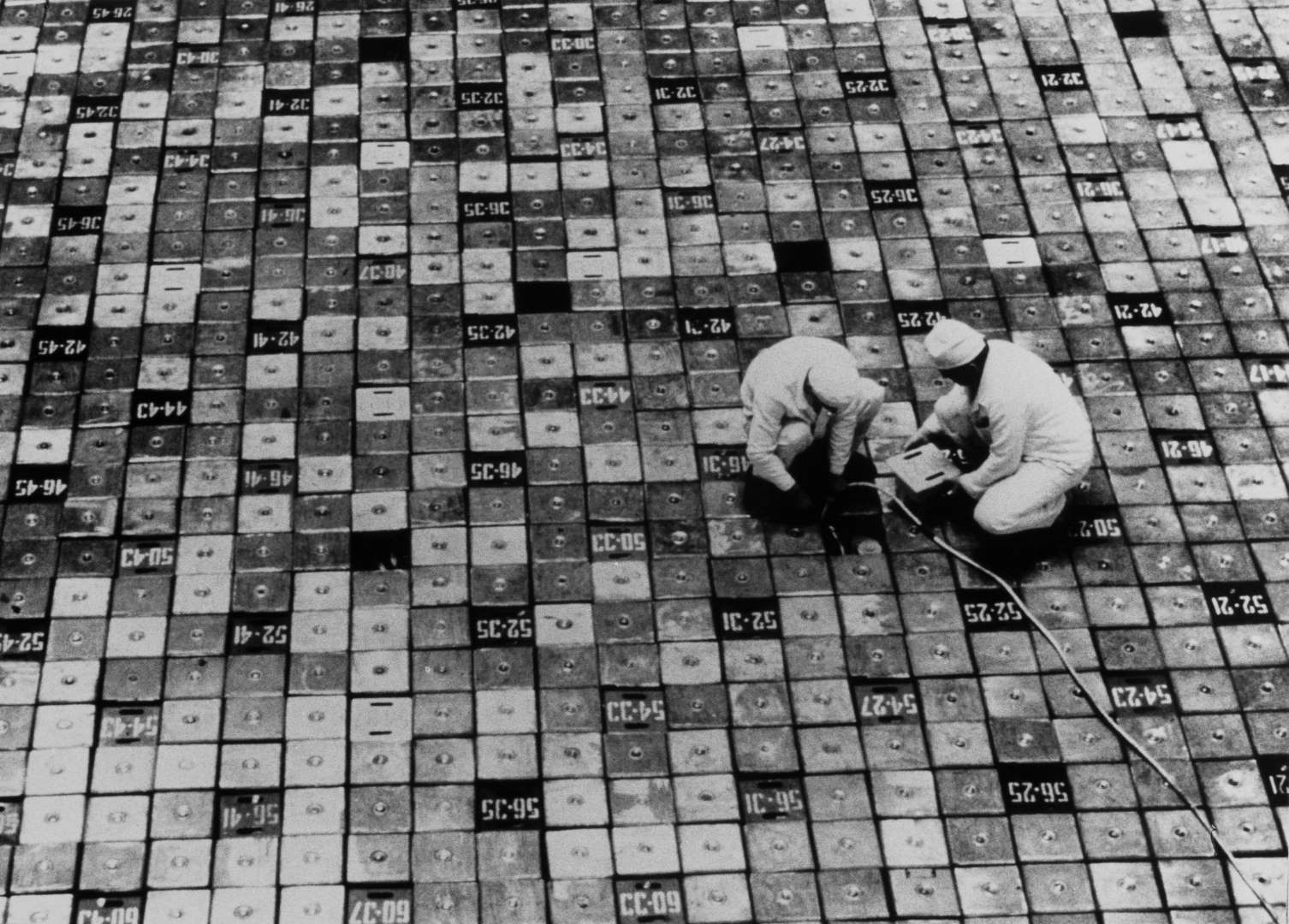

“At the peak of the cleanup, an estimated 600,000 workers were involved in tasks such as building waste repositories, water filtration systems, and the ‘sarcophagus’ that entombs the rubble of Chernobyl reactor number four. They also built settlements and towns for plant workers and evacuees,” writes Marianne Lavelle. “The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) says some 350,000 of the liquidators in the initial plant cleanup received average total body radiation doses of 100 millisieverts. That’s a dose equal to about 1,000 chest x-rays and about five times the maximum dose permitted for workers in nuclear facilities.”

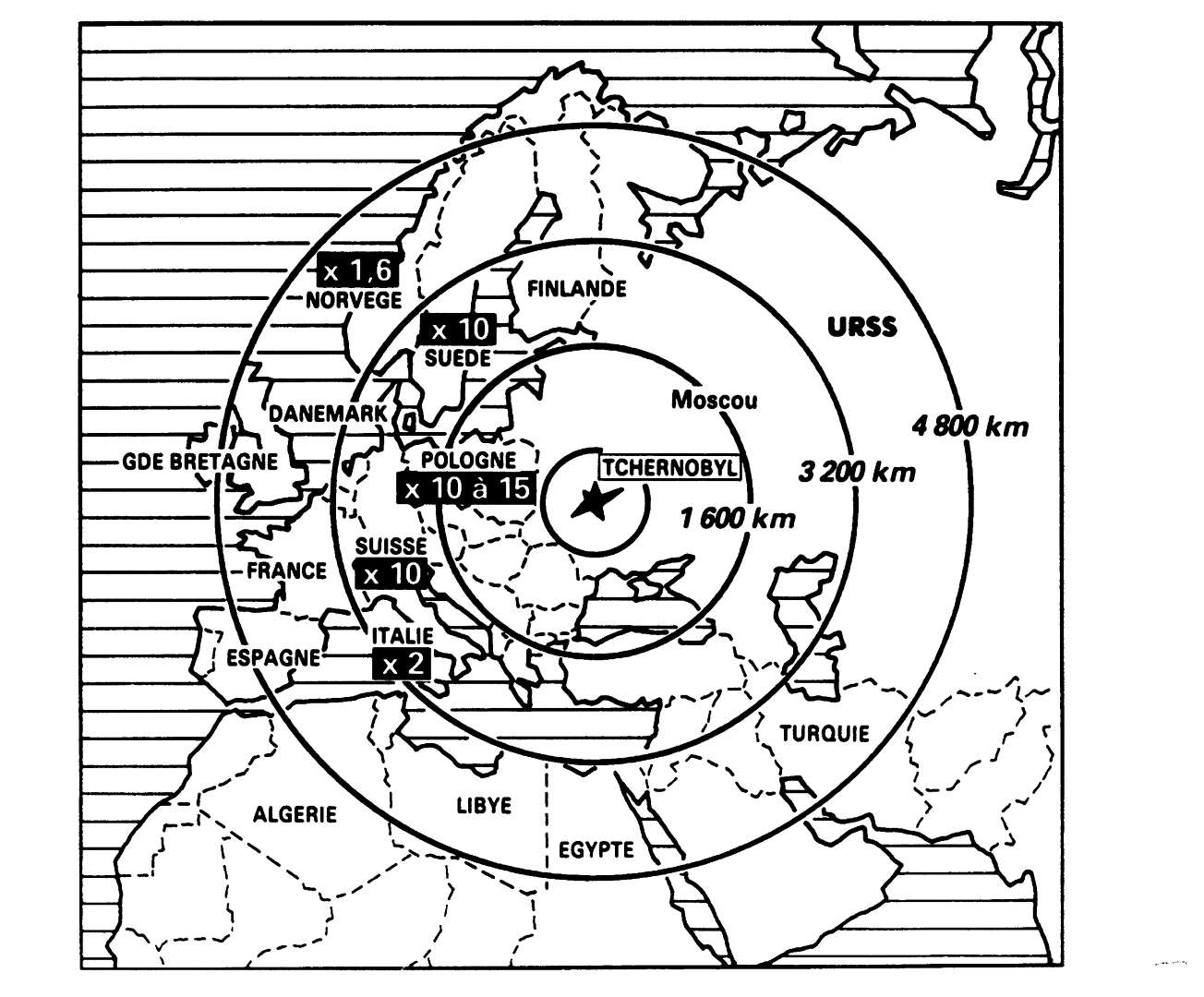

The affect on the land and agriculture was massive. Kate Brown writes that truckers “loaded 50,000 head of cows, sheep and goats onto flatbed trucks. Most of these animals had remained outdoors after the accident, grazing on contaminated grass under clouds of radioactive gases. Half of the animals were too contaminated to keep, and 25,000 were sent immediately to slaughterhouses.” The contaminated meat was mixed with safe meat, mashed into sausages and sold throughout the USSR. “The only place they could not deliver the contaminated sausages, the regulations made clear, were stores in Moscow, where the men who had written the new, post-accident regulations lived.” Propaganda trumped containment. Not until Sweden discovered a radiation cloud that had drifted across Europe was the true extent of the Chernobyl explosion revealed.

A few days after the deadly explosion at Chernobyl, Ukrainians in Kiev were out in force for International Workers’ Day. On May 1, 1986. Thousands attended the annual May Day parade. All around were invisible clouds of fatal radiation.

Children sick from radiation in a hospital ward in Syekovo, near the Chernobyl nuclear plant on April 21, 1990.

Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev opined that the Chernobyl explosion was “perhaps the real cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union.” It was the “turning point” that “opened the possibility of much greater freedom of expression, to the point that the system as we knew it could no longer continue.” The blast delivered a fatal blow to leaders who had carried on regardless as their comrades suffered.

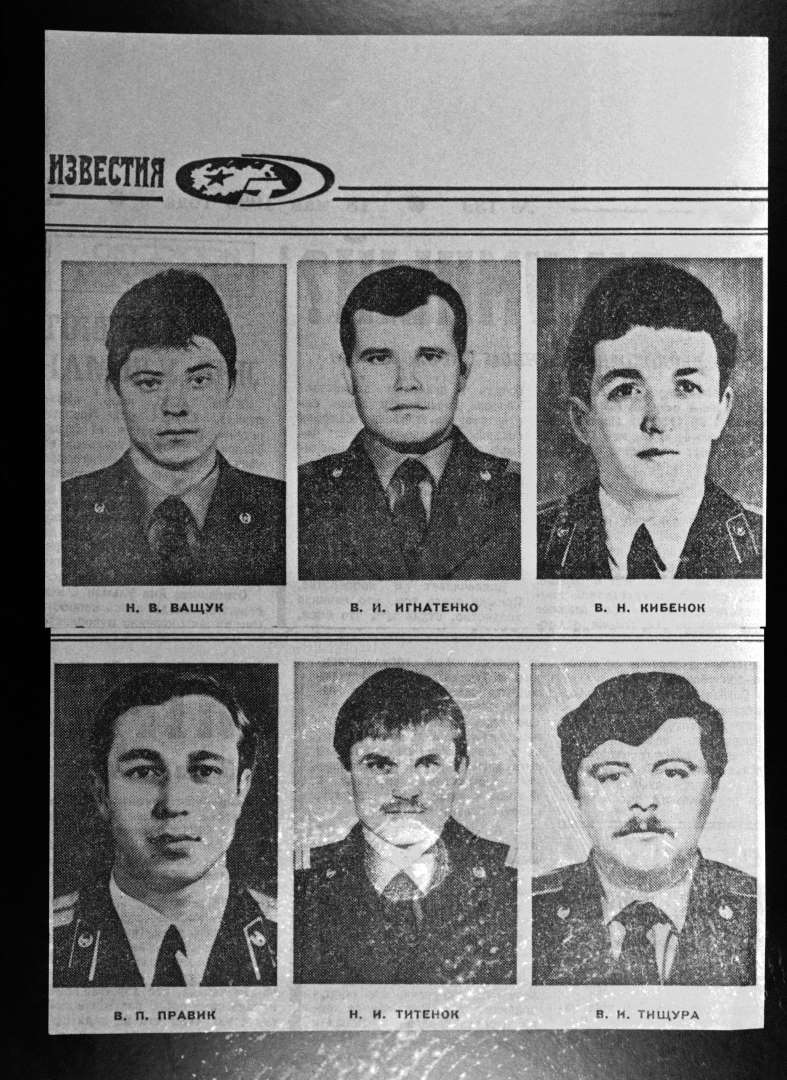

The Soviet newspaper Izvestia published these photographs of the six firemen shown who died as a result of exposure to radiation while battling the fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. The unofficial death toll was 13 on Monday, based on a report from U.S. bone marrow specialist Dr. Robert Gale. The firemen were identified as (left to right, top): I.V. Vashchuk, V.I. Ignatenko, V.N. Kibenok; and (bottom) V.P. Pravik, N.I. Titenok, and V.I. Tishchura – 19 May 1986

In 2006, Gorbachov, an architect of ‘glasnost’ (openness and freedom of expression) was at pains to excuse the Politburo:

The Politburo did not immediately have appropriate and complete information that would have reflected the situation after the explosion. Nevertheless, it was the general consensus of the Politburo that we should openly deliver the information upon receiving it. This would be in the spirit of the glasnost policy that was by then already established in the Soviet Union.

Thus, claims that the Politburo engaged in concealment of information about the disaster is far from the truth. One reason I believe that there was no deliberate deception is that, when the governmental commission visited the scene right after the disaster and stayed overnight in Polesie, near Chernobyl, its members all had dinner with regular food and water, and they moved about without respirators, like everybody else who worked there. If the local administration or the scientists knew the real impact of the disaster, they would not have risked doing this.

In fact, nobody knew the truth, and that is why all our attempts to receive full information about the extent of the catastrophe were in vain. We initially believed that the main impact of the explosion would be in Ukraine, but Belarus, to the northwest, was hit even worse, and then Poland and Sweden suffered the consequences.Of course, the world first learnt of the Chernobyl disaster from Swedish scientists, creating the impression that we were hiding something. But in truth we had nothing to hide, as we simply had no information for a day and a half. Only a few days later, we learnt that what happened was not a simple accident, but a genuine nuclear catastrophe — an explosion of Chernobyl’s fourth reactor.

Interior view of the control room of Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant unit 3. Over 3,000 people continued to work at Chernobyl to monitor nuclear fuel and carry out the decommissioning of the facility.

In 2016, Efrem Lukatsky, a Kiev-based photographer for The Associated Press, who lived close to the accident, recalled:

It was two full days after the April 26, 1986, explosion when the Soviet Union’s tightly controlled news media acknowledged that anything had happened — and the reports’ dishonesty was as bad as no news at all. The Tass news agency called it an “unlucky accident” and said there was nothing to worry about.

Nobody canceled a May Day parade in Kiev that saw thousands of people walking in columns along the streets, with songs, flowers and Soviet leaders’ portraits, covered with invisible clouds of fatal radiation. A thick cloud of smoke was carrying radioactive poisons over much of Europe.

The only reliable source of information was the Voice of America, but the KGB was jamming the signal. If the signal got through, we heard doctors advising us to take a daily drop of iodine to protect our thyroids from radiation.

Away from the politics, people were dying and becoming infected with huge doses of dangerous radiation.

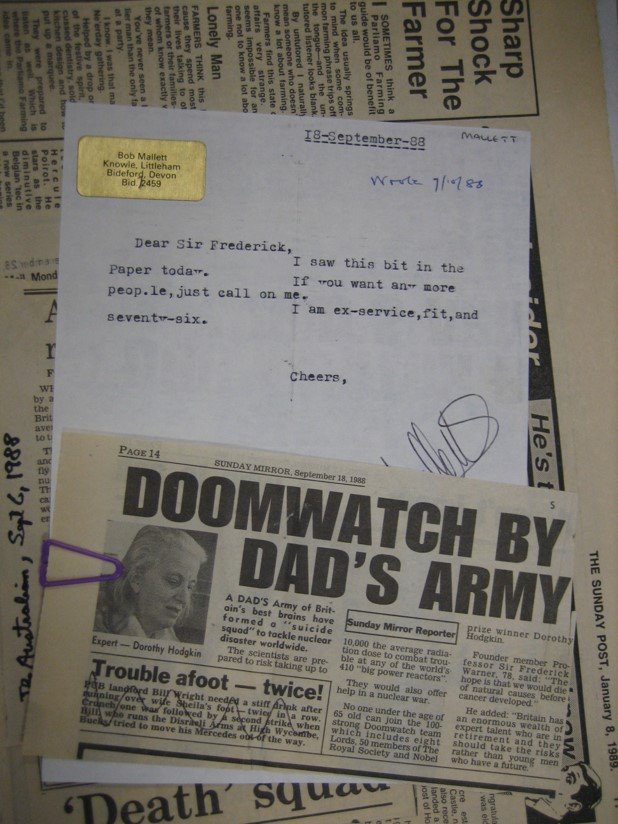

Via Jon Agar

“In November 1986, Warner sent letters to all Fellows of the Royal Society (FRSs) and the Fellowship of Engineering (FEngs) aged over 65, inviting them to volunteer,” writes Jon Agar. “Many replied positively. As newspapers picked up on the story, others volunteered too. Warner compiled a list of over a hundred volunteers and assigned them to regional stations. Perhaps the most unexpected volunteer was the philosopher Karl Popper. He was assigned to protect the London area in the advent of a nuclear incident.

“In the letters replying to Warner, the volunteers often gave reasons for volunteering: public service, not least strong nostalgia for wartime service, and a demonstration of support for the UK nuclear projects were foremost. The letters, which are in Warner’s archived papers at the University of Essex, expressed the values of a generation that had been forged in the war, had built the nuclear world, and was now willing to sacrifice aged bodies in return.”

Pripyat, Ukrainian USSR – The monument ‘taming of the fire’ devoted to the builders of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, December 1, 1979.

Via: Jon Agar

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.