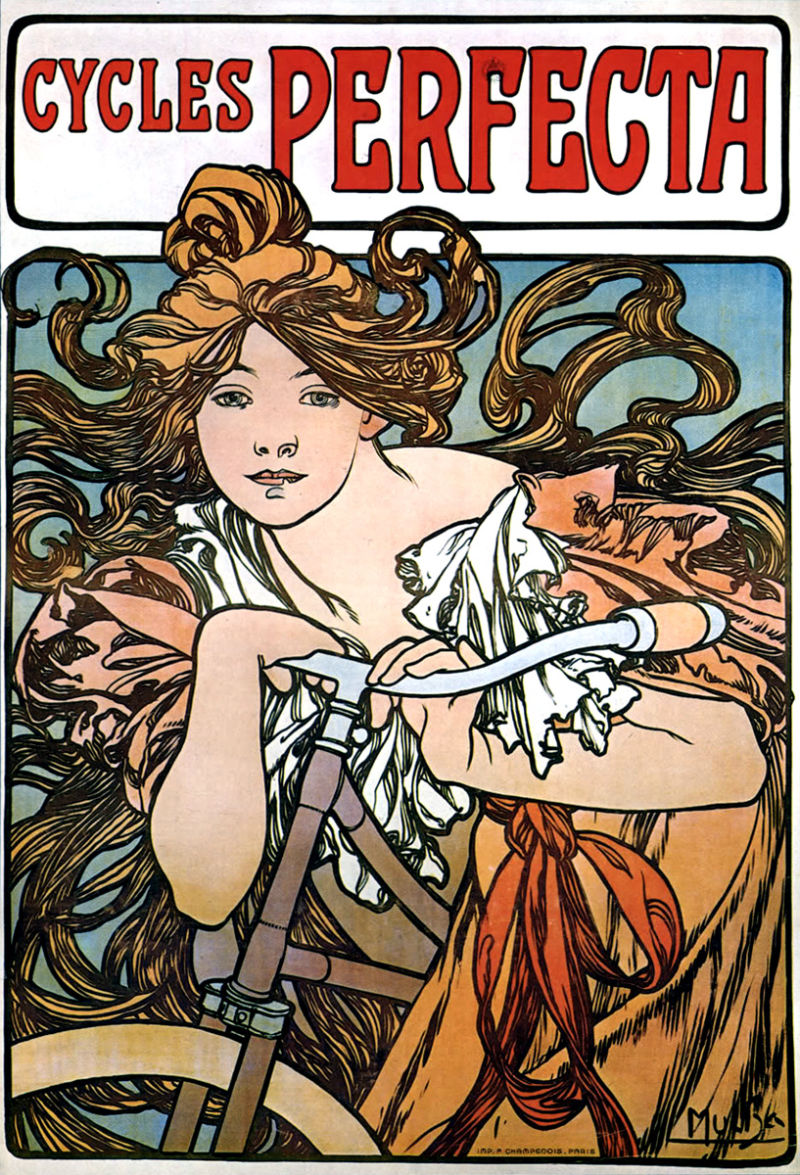

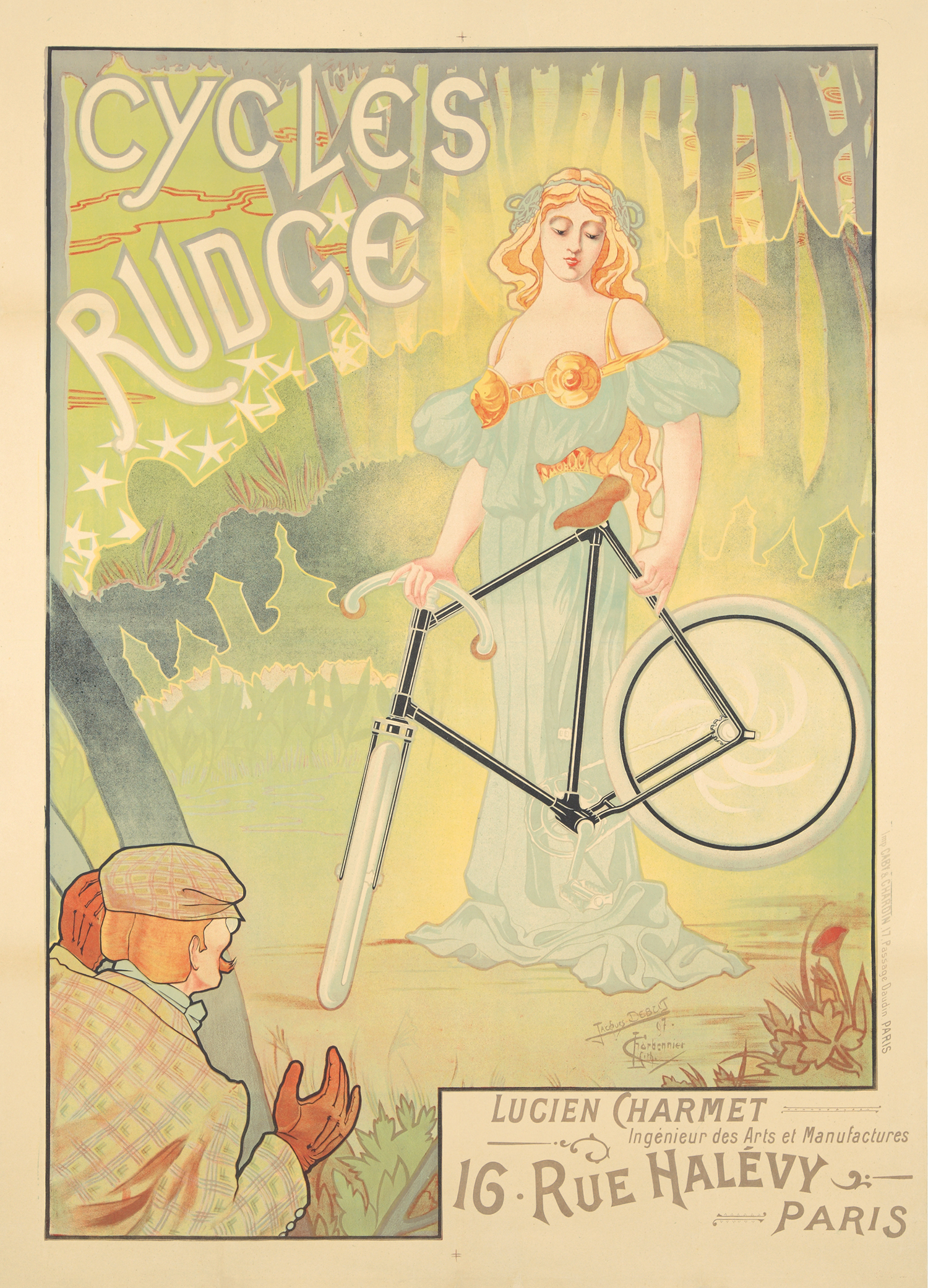

The civil rights leader, Susan Brownell Anthony, who played a significant role in American women’s suffrage, was interviewed in the New York World in 1896, and said:

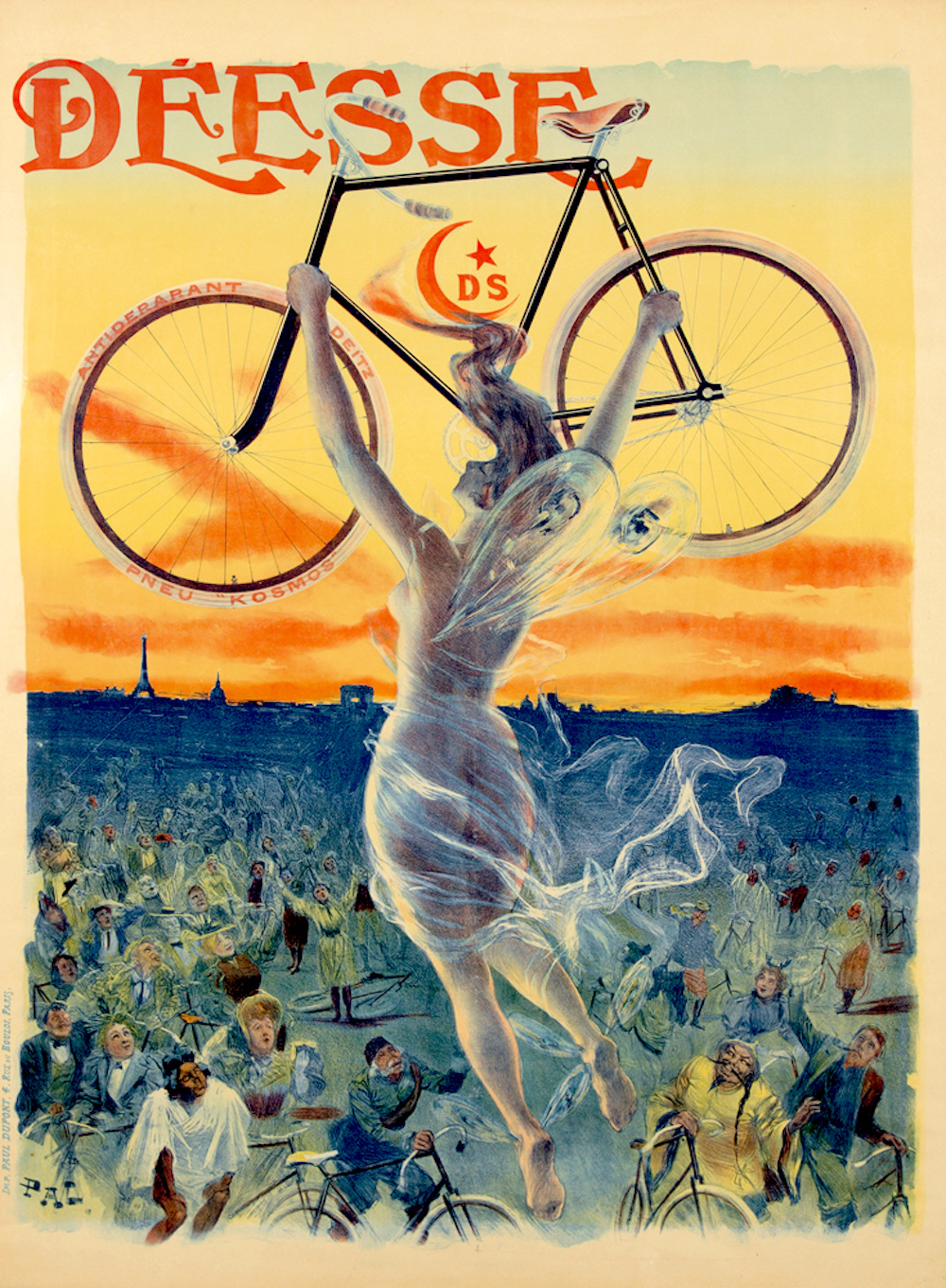

I think [the bicycle] has done more to emancipate women than any one thing in the world. I rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a bike. It gives her a feeling of self-reliance and independence the moment she takes her seat; and away she goes, the picture of untrammelled womanhood.

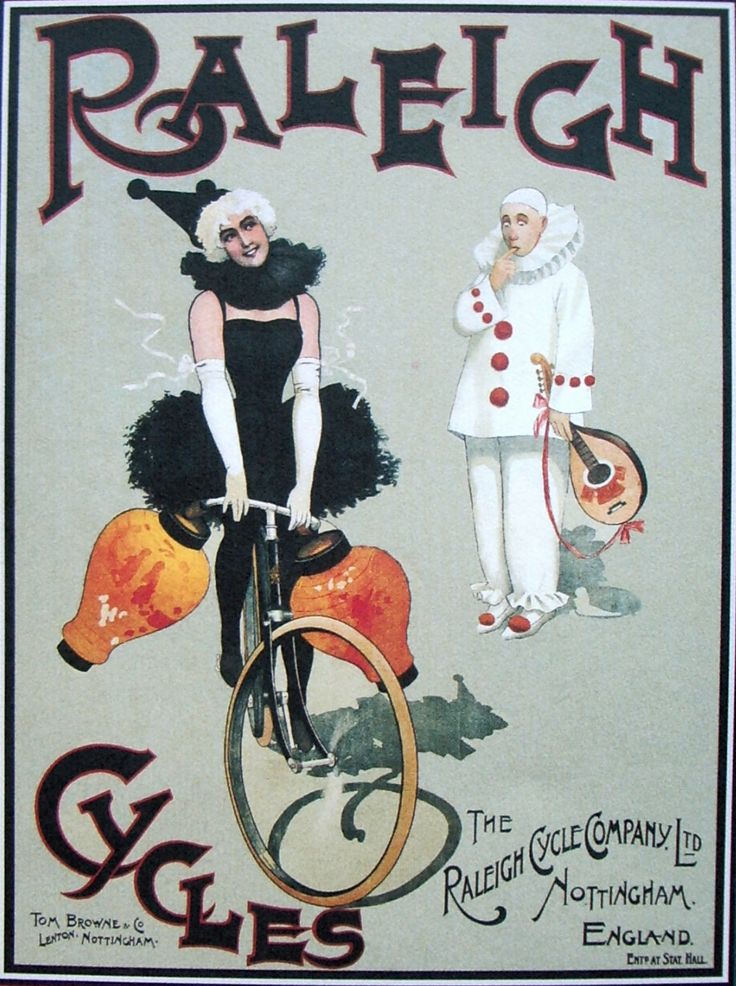

It was the height of the American bicycle craze, or at least what was thought of as a craze, and the following year, in 1897, more than two million bicycles were sold in the United States. Of course it wasn’t just in America that women were taking to bicycles in great numbers. In the same year a ‘lady correspondent’ in the Manchester Guardian reported that:

The coming summer will be the ladies’ season as far as cycling is concerned. Almost everyone one knows is buying a bicycle or talking of buying one.

The amusing point about the cycling mania as it affects the feminine world is that not only the young and frivolous but the staid and middle-aged are swayed by it. The lady may be no longer young; she may be stout; she may never have been known to depart by one hairsbreadth from the narrowest accepted canon of propriety. It is of no avail: none of these things shall save her: if she is not an absolute cripple, she will be seen this summer careering along the roads on a bicycle along with the youngest and giddiest of her sex.

Phebus Cycles – According to Fanny Erskine in Lady Cycling: “Some wise people say that corsets should be discarded for cycling. This is not correct. There should be no approach to tight-lacing, but a pair of woollen-cased corsets afford great support; they keep the figure from going all abroad, and protect the vital parts from chills.”

It was the invention of what was called the Safety Bicycle that changed everything – especially for women. It was a direct ancestor of what we ride today and had a chain, normal sized wheels and what was called a diamond frame. Although something similar had been developed a few years earlier the first bicycle to be called a “safety” was designed by the English engineer Henry (Harry) John Lawson in 1876. Unlike ‘penny-farthings’ or ‘ordinaries’ which had the huge front wheels and were ridiculously dangerous, the rider’s feet were within reach of the ground, making it easier to stop and, more importantly, stay on. An American cycling magazine, The Bearings, put it in 1894:

The [safety] bicycle fills a much-needed want for women in any station of life. It knows no class distinction, is within reach of all, and rich and poor alike have the opportunity of enjoying this popular and healthful exercise.

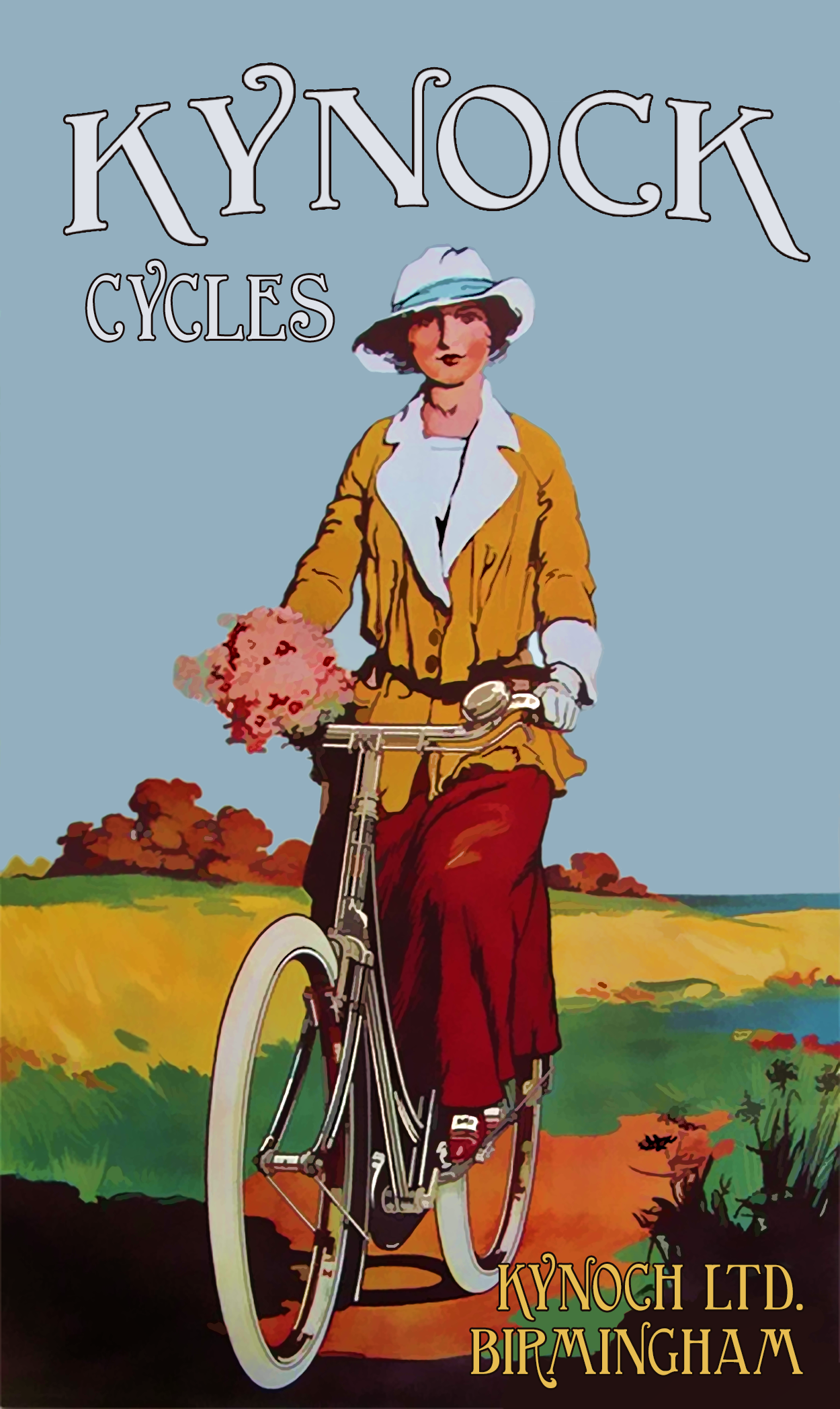

Elizabeth Robins Pennell, the American cookery writer and art critic but who had made her home in London, wrote on the subject of Cycling for Women in the Gentlewoman in 1893: “Some people have questioned whether cycling is healthy for women; but their doubts are based on ignorance. In the first place, the work is not so hard as it looks. Given a good road and no head wind, a bicycle, after a certain point, goes almost by itself…the labour is nothing compared to that of dancing all night or of shopping all day.

Two years later in the summer of 1895 an article appeared in the Manchester Guardian entitled ‘The Joys of Cycling by a Middle-Aged woman’: A charm in cycling is the ease with which one casts off all restraint when once one becomes indifferent to remark and criticism. A delightful feeling of “abandon” possesses us, and we almost lose our own individuality in a sense of absolute freedom. Perhaps some of the freedom is due to the light and simple mode of dress necessary in cycling.

The incredibly restrictive dress of the late Victorian woman was certainly not conducive to riding bicycles and although controversial for many, women’s fashion began to change in order to comfortably ride them. In the Daily Telegraph in an article called ‘The Chains that Set Women Free’ Bella Bathurst, author of The Bicycle Book, quotes the authors of the Badminton Cycling Guide, published in 1887. They recommended that no female cyclist should ever leave home without a pair of sturdy woollen combinations, thick merino stockings, knickerbockers with a pair of worsted trousers on top, a plain gathered skirt in ”a happy grey medium’’, a jacket, a hat and a pair of doe-skin gloves. Bathurst also quotes Swiftsure, a columnist for the socialist weekly The Clarion, who thought the whole idea a joke. “It requires no small amount of resolution to ride out in knickers,” he wrote, “but I feel sure that in time the custom will be almost universal.”

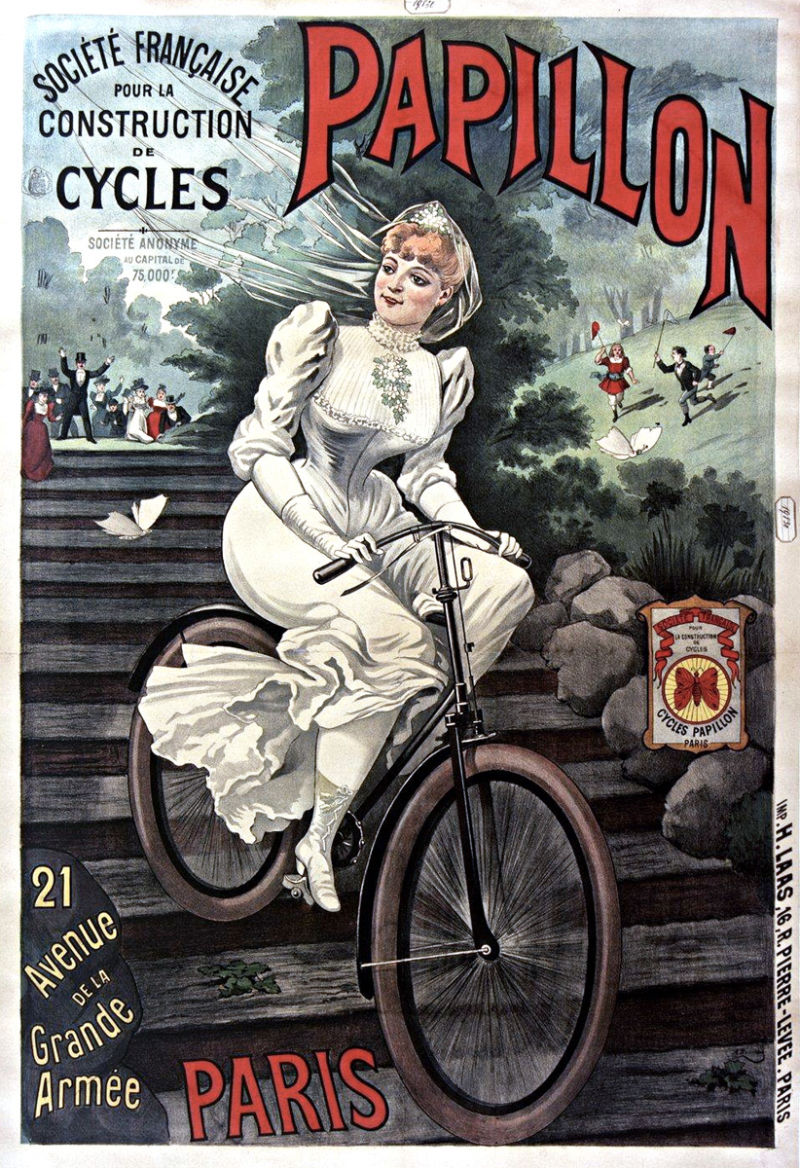

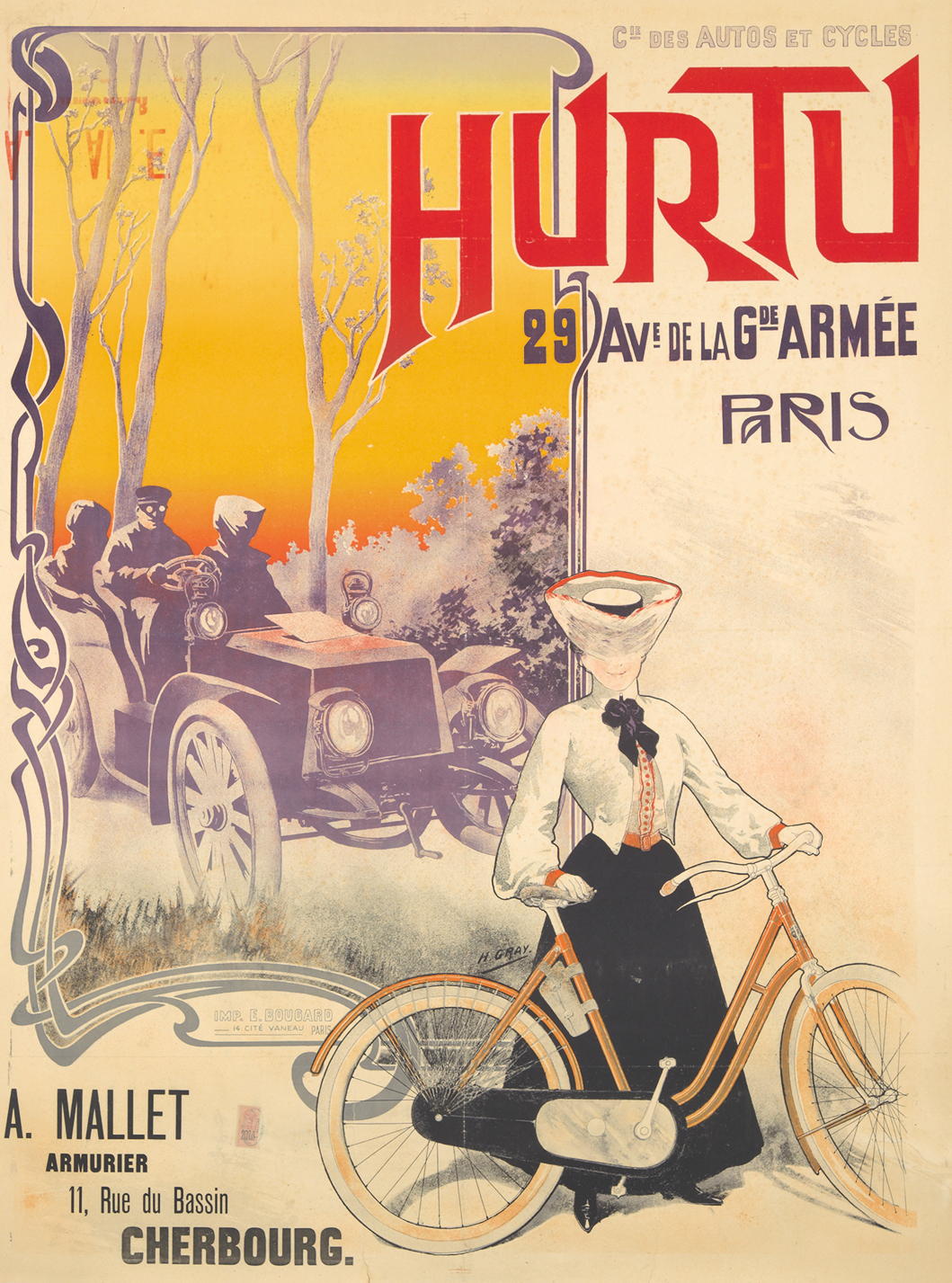

In 1895 the Manchester Guardian reported that even in fashionable Paris women of all classes of society were wearing ‘ample divided skirts or knickerbockers’ and these were not only in the Bois de Boulogne, but on the boulevards and all the main thoroughfares of the French capital. The Paris correspondent of the London Standard was shocked to see that the cycling costumes were also being worn when shopping and even sitting at cafe tables. The Guardian also quoted the opinions of some stars of the Parisian stage most of whom it has to be said were neither fans of the new-fangled bicycle or the clothes required to comfortably ride them. The fifty year old esteemed actress Madame Sarah Bernhardt stated that although she preferred long skirts to knickerbockers and divided skirts argued that the use of bicycles by young women were:

Transforming our manners and customs more profoundly than people generally think. The actress who gained her fame by essentially staying indoors continued, ‘I am of the opinion that the outdoor life encouraged by the bicycle may have dangerous and very grave consequences.

Madame Nellie Melba, who admitted to having no great liking for bicycles, declared,

I abhor masculine costume for women. It is ugly and I have, even on stage, never consented to wear it…how wounded I feel in my artistic and feminine preferences when I see women dress themselves as they do.

Mlle. Brandes (of the Comédie Française) said that as a woman and artist she considered –

The full knickerbockers or double skirt is seldom acceptable. It is a brutal garment which is often ridiculous. How can a woman sacrifice the noble bearing which a rhythmical step gives so easily to a long skirt?

It wasn’t just the unsuitable clothes that women wore in the 1890s that was a hindrance for women riding bicycles. Bella Bathurst again:

It was also the sheer fact of sitting astride something. At this stage in the late 19th century, nicely brought up young ladies were discouraged even as children from sitting on see-saws or riding on hobby horses, and no girl over the age of 14 would do anything to prove they had legs.

Since women had successfully ridden horses side-saddle for centuries, it seemed reasonable to suppose that they could do the same thing with bicycles. Besides, the results of sitting astride a machine and then leaning forward were too horrible to contemplate. The constant friction of the saddle must inevitably lead to a new race of pop-eyed nymphomaniacs riding round Britain in a state of frenzied arousal. Cycling would ruin the ”feminine organs of matrimonial necessity’’, according to one French expert.

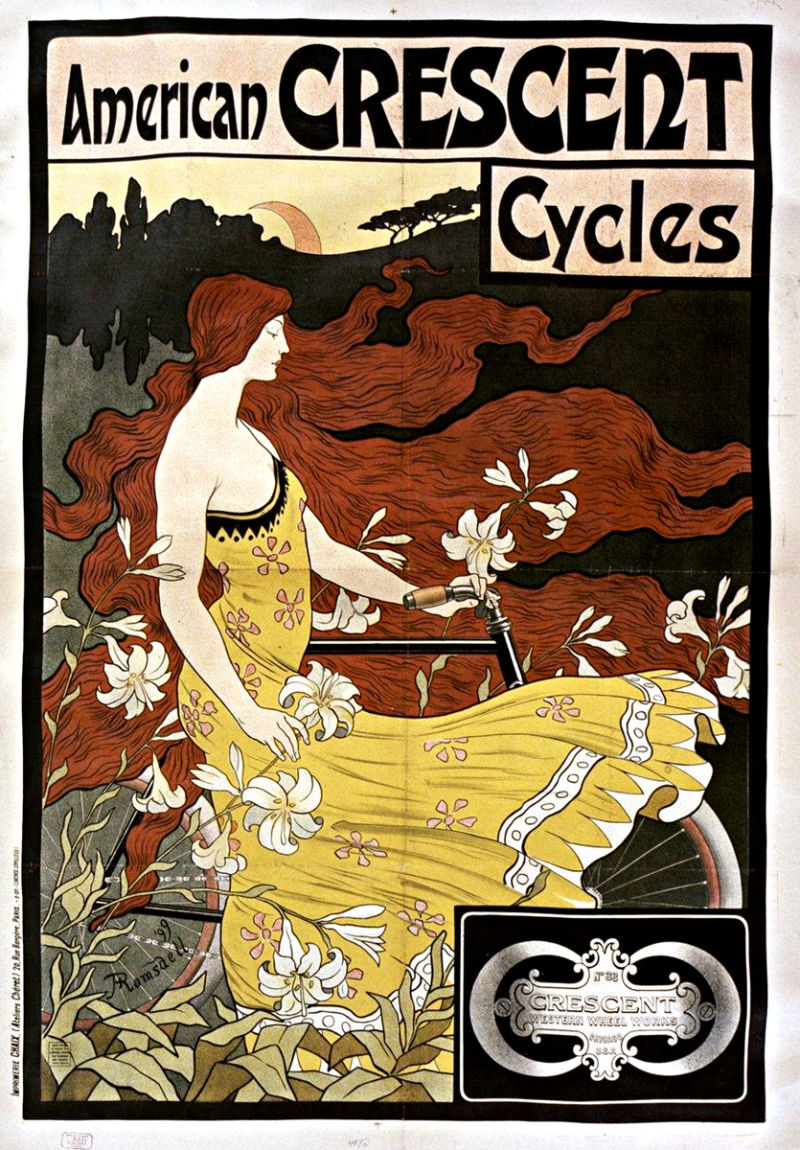

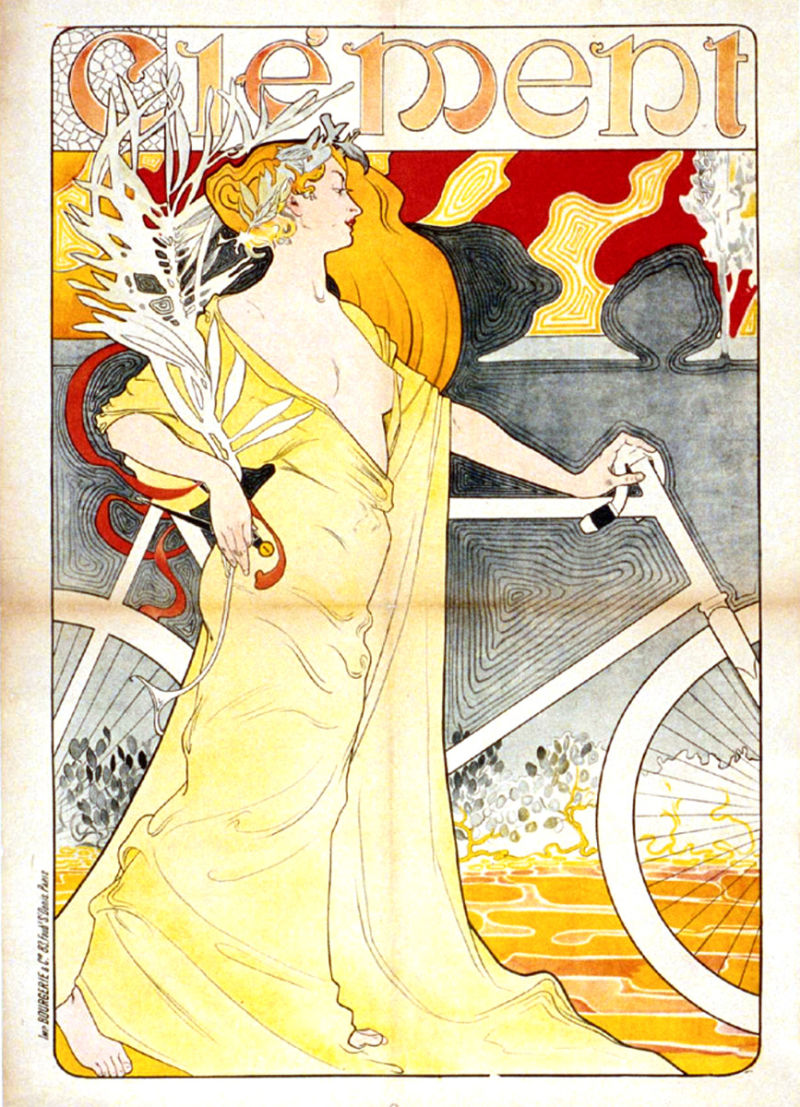

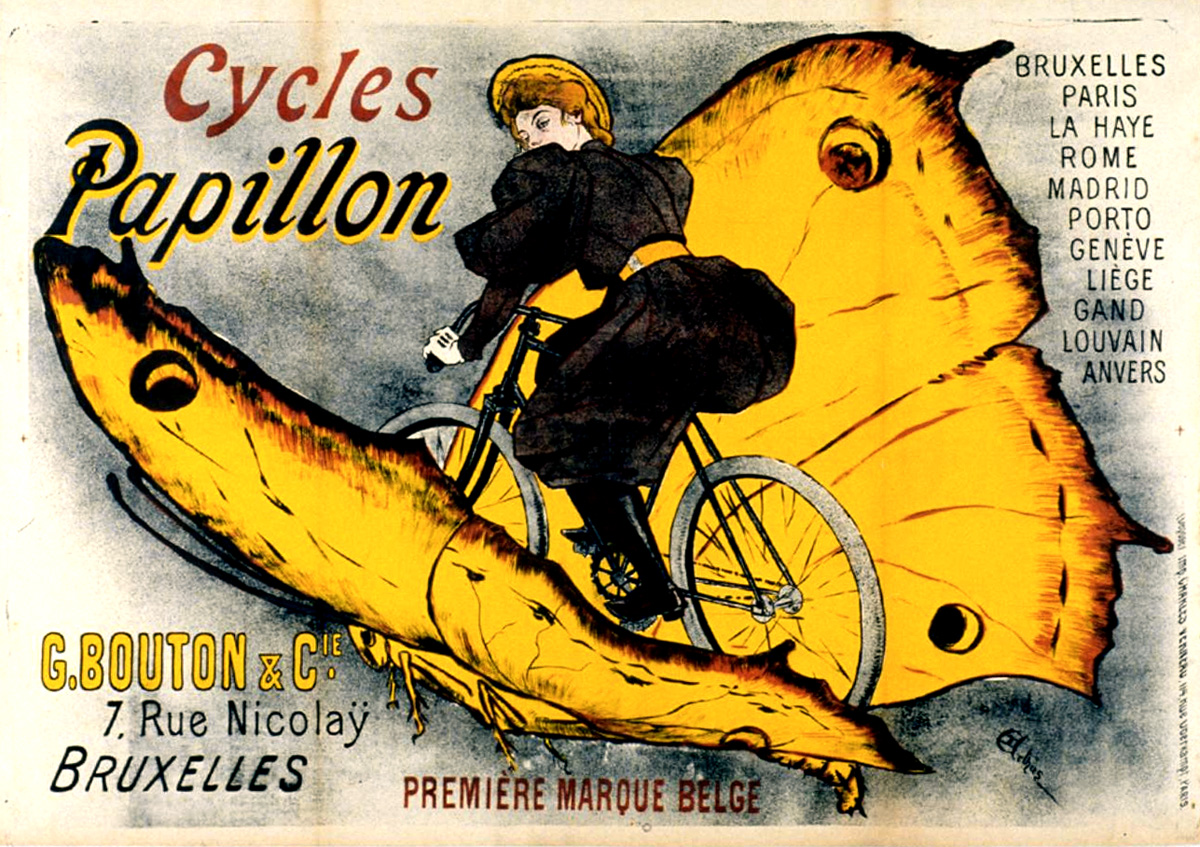

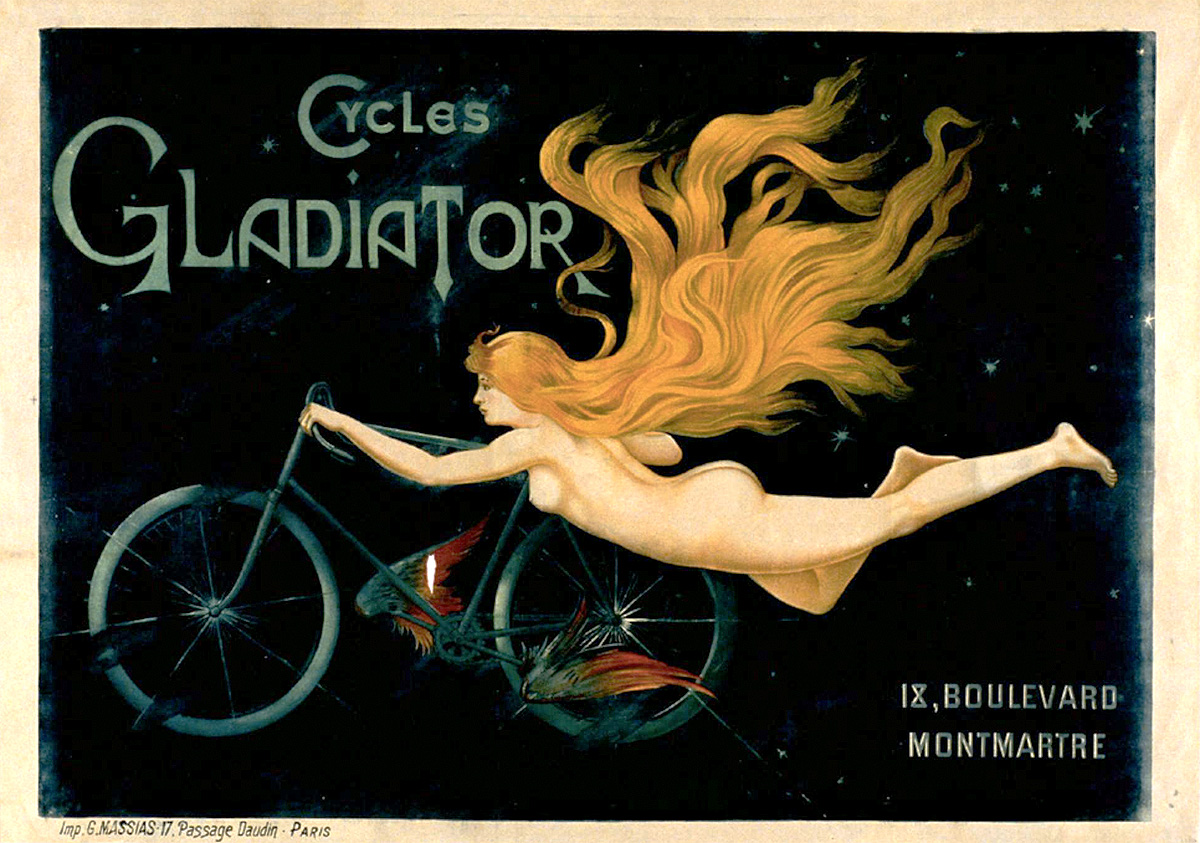

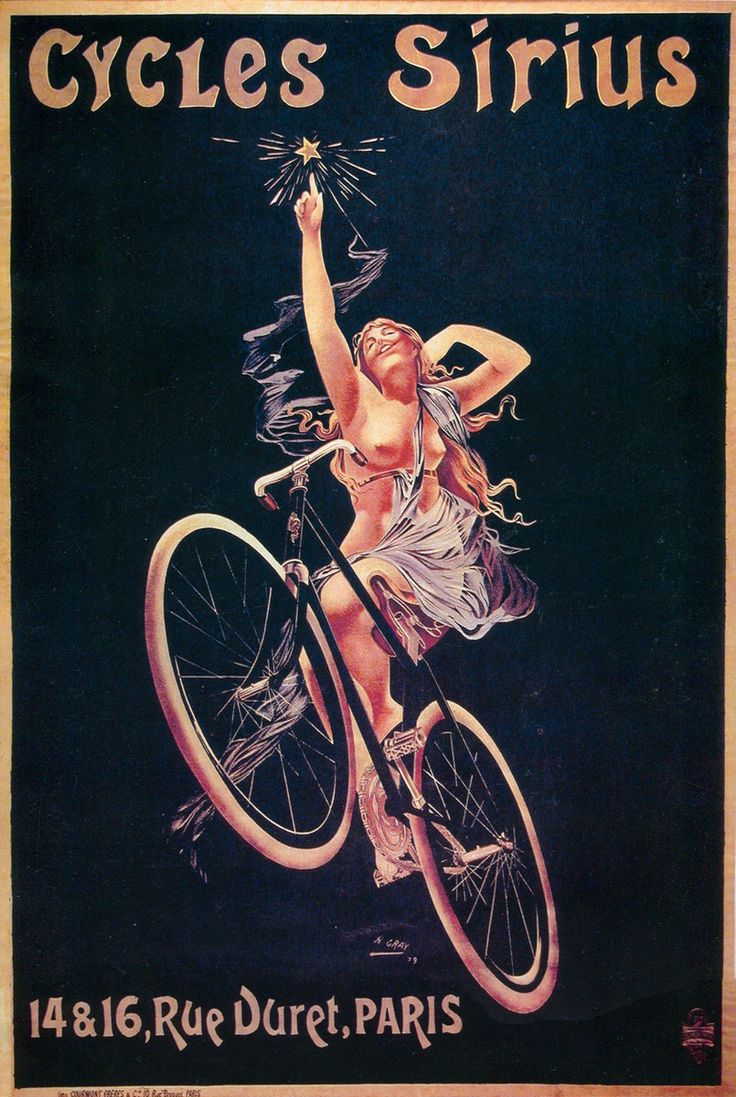

At the end of the 19th century the bicycle was becoming far more than just another way of getting from A to B – it meant that women had a relatively cheap form of independent transport – a means to break free from house and husband. Today the bicycle is perhaps taken for granted but despite the technological advances incorporated in the modern version it’s completely recognisable to the ones pedalled by the knickerbocker and split-skirt wearing women of the late Victorian age. Almost exactly 120 years after Susan B. Anthony spoke of ‘untrammelled womanhood’ the humble bicycle still symbolises freedom and liberation for everyone.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.