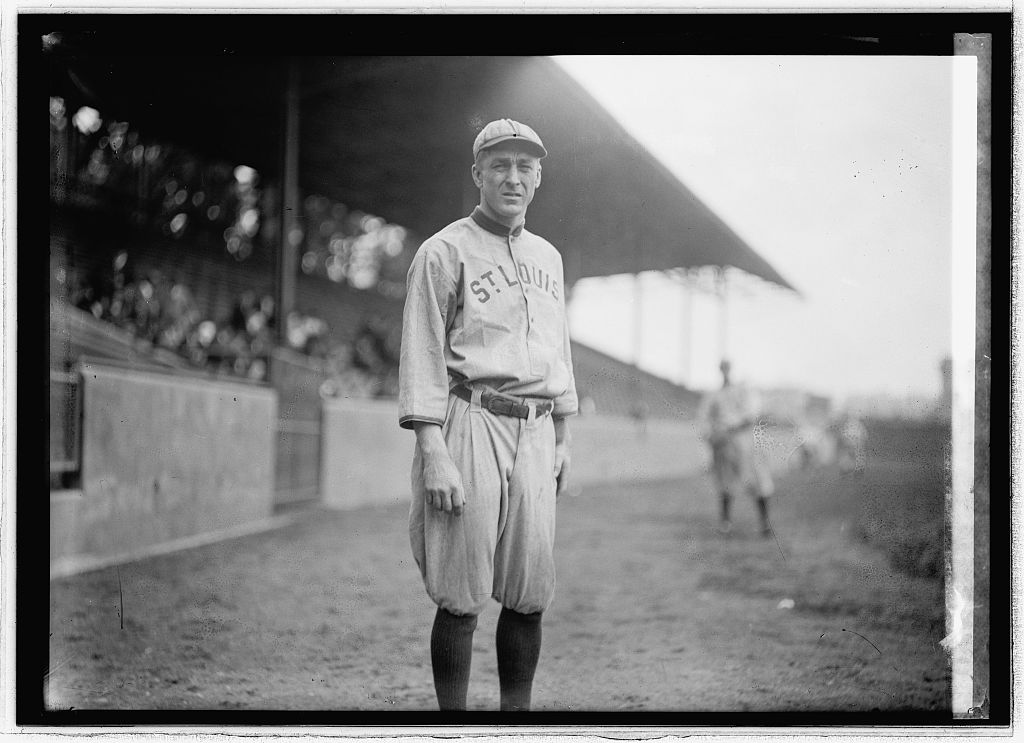

Branch Rickey (1881–1965) is best known for breaking the color bar when he brought Jackie Robinson (1919-1972) into major league baseball in 1947. Rickey, who represented the St. Louis Browns, St. Louis Cardinals, Brooklyn Dodgers, and Pittsburgh Pirates, scouted many more players throughout the 1950s and 1960s, especially for the St. Louis Cardinals. His reports on each player are a great read, laying out in black and white Rickey’s skill in analyzing almost every aspect of a player’s game and talent.

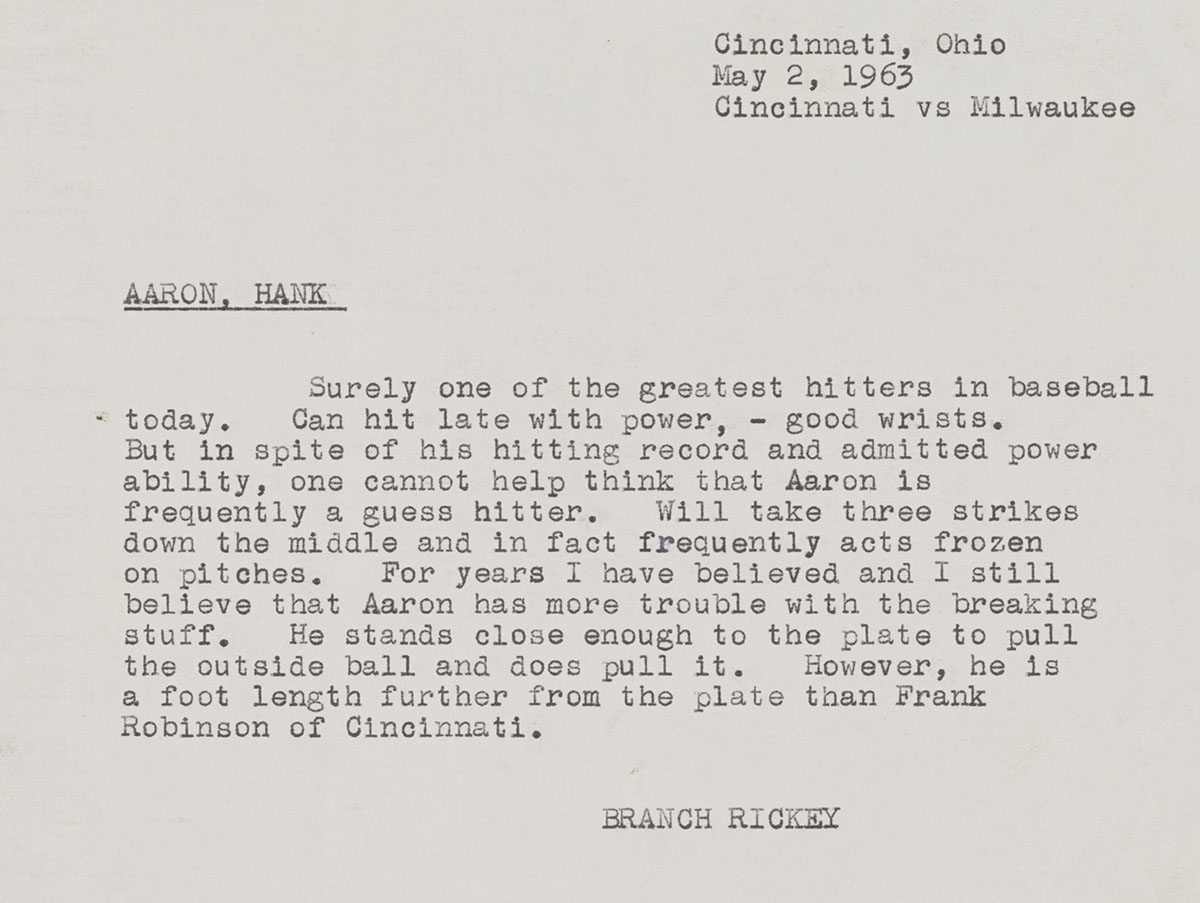

On Henry Aaron: The greatest home-run hitter of the 20th century, “[I]n spite of his hitting record and admitted power ability, one cannot help think that Aaron is frequently a guess hitter.”

On Willie Mays: “I would pitch a lot of slow stuff to Mays, particularly when he is anxious to hit. The slow curve ball he ‘slobbers’ all over the place.”

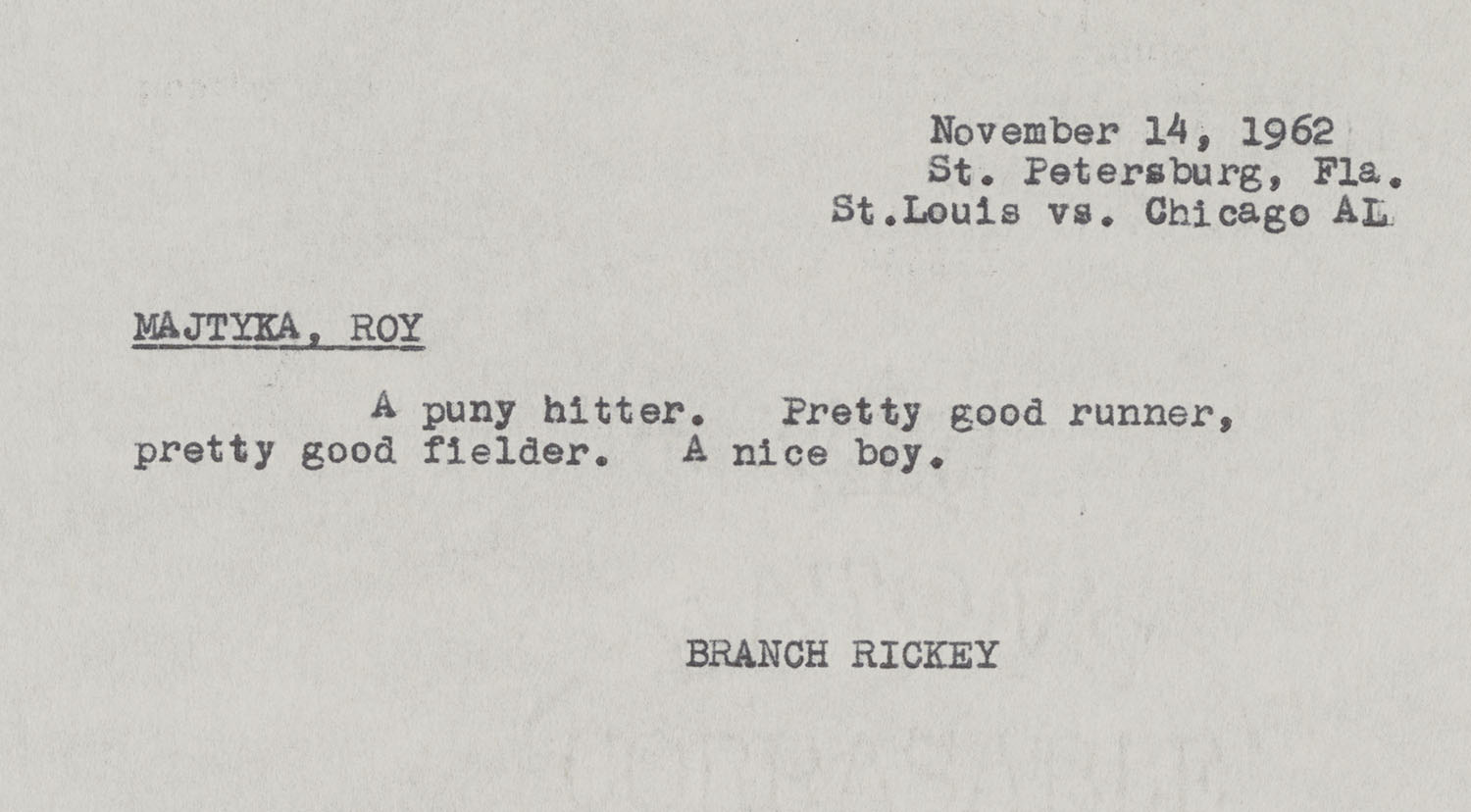

On Roy Majtyka: “…a puny hitter. Pretty good runner, pretty good fielder. A nice boy.”

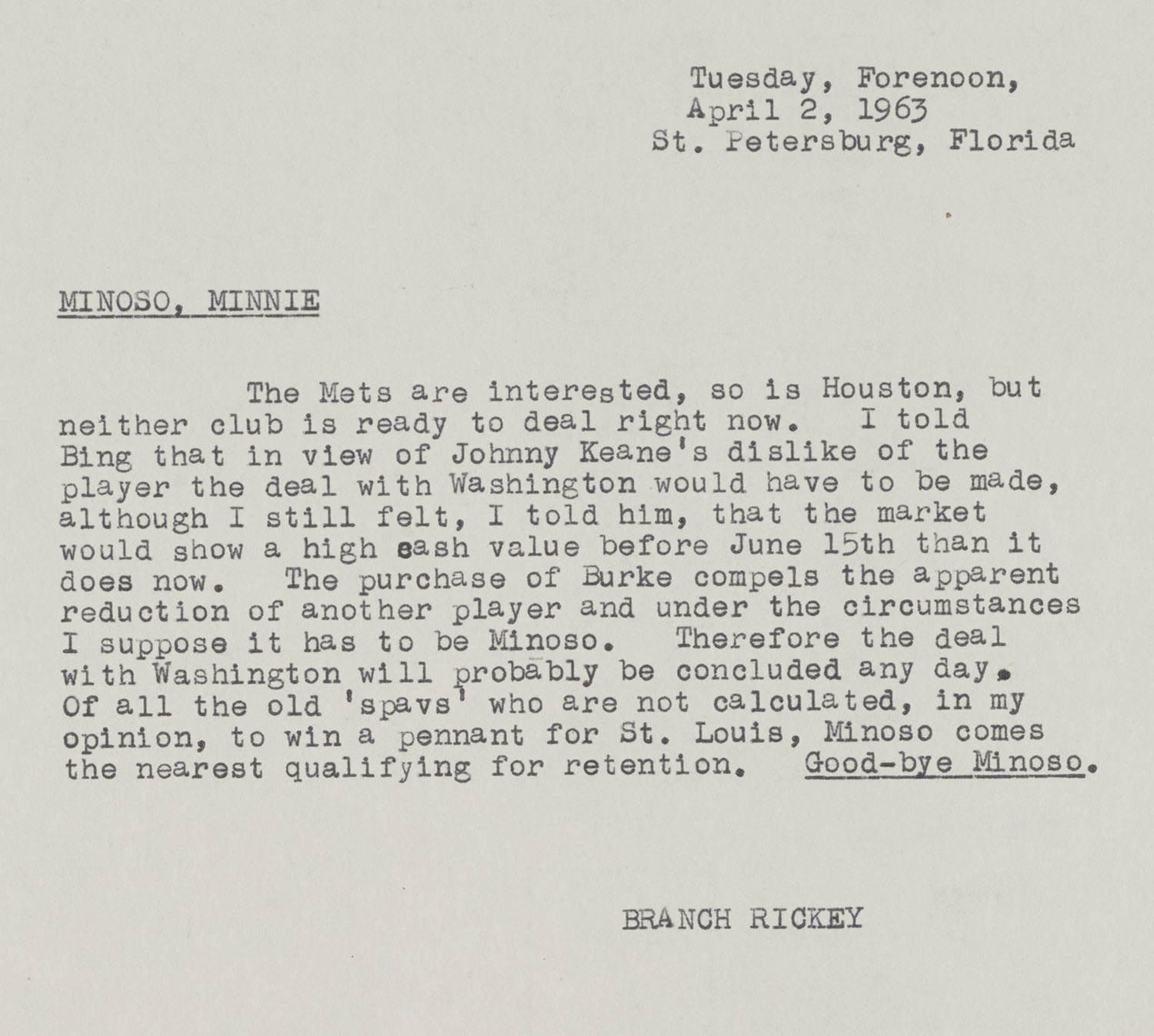

On Orestes “Minnie” Minoso: “[O]f all the old ‘spavs’ who are not calculated, in my opinion, to win a pennant for St. Louis, Minoso comes the nearest qualifying for retention. Good-bye Minoso.”

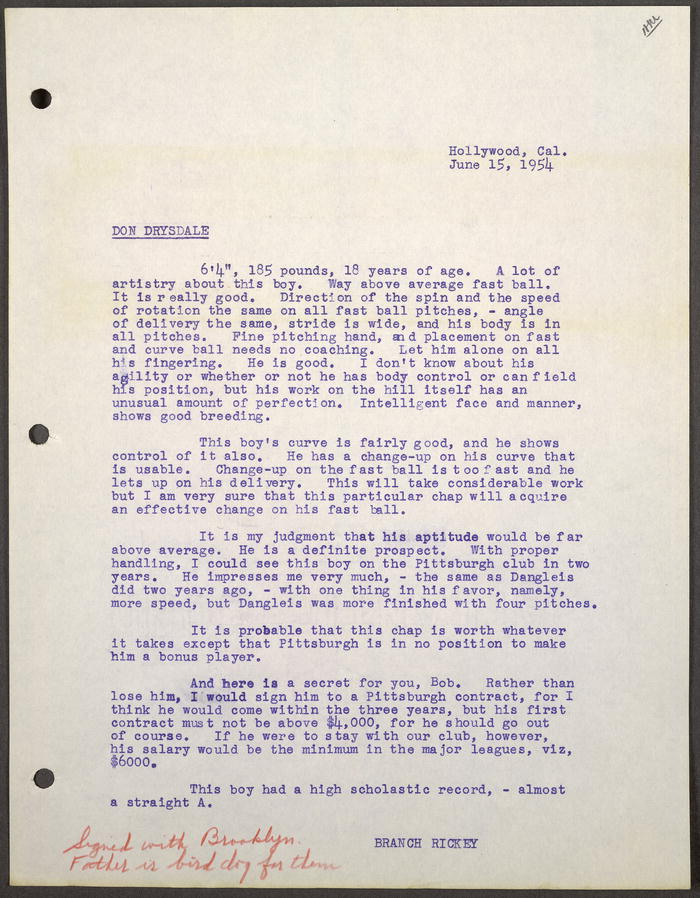

On Donald S. Drysdale:

John J. McDonough writes:

He never played for the Pirates. Drysdale signed with the Dodgers, for whom his father was a scout. He then spent his entire major league career of fourteen years with the Dodgers franchise, first in Brooklyn and then in Los Angeles. He led the National League in strikeouts three years and won the Cy Young Award as the best pitcher in baseball in 1962. He was elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1984. Branch Rickey had preceded him there in 1967.

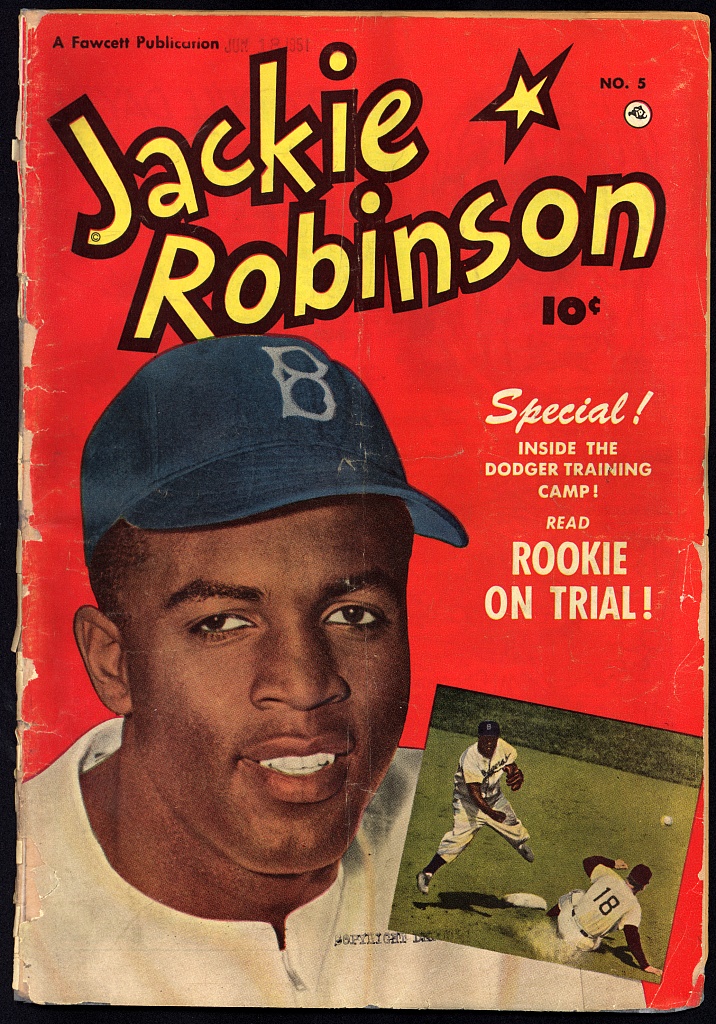

Robinson played himself and Minor Watson played Dodgers president Branch Rickey in “The Jackie Robinson Story,” 1950

And on Jackie Robinson. Rickey spoke with Davis J. Walsh in 1955.

Before that, a little background on baseball’s “color bar”:

African Americans played baseball throughout the 1800s. By the 1860s notable black amateur teams, such as the Colored Union Club in Brooklyn, New York, and the Pythian Club, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, had formed. All-black professional teams began in the 1880s, among them the St. Louis Black Stockings and the Cuban Giants (of New York). Reflecting American society in general, amateur and professional baseball remained largely segregated.

One of the few black players on an integrated professional league team was Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker, a catcher for the minor league Toledo Blue Stockings. In 1883, the Chicago White Stockings, led by star player Adrian “Cap” Anson, refused to take the field against the Blue Stockings because of Walker’s presence. The Blue Stockings manager insisted that the game be played, and Anson relented. When the Blue Stockings joined the American Association in 1884, Walker became the first African-American major leaguer. In July of 1887, the International League banned future contracts with black players, although it allowed black players already under contract to stay on its teams. These are but two of the events that shaped the unwritten “color line,” which segregated professional baseball until the 1940s.

Davis: …let’s get to Jackie Robinson – that’s one of the high points of your career certainly, if not the highest, you broke the colored line in baseball, how far do you want to discuss that?

Rickey: Well, I have so many angles, I think it is in the course of permanent solution – I am deeply gratified if it has had any effect at all upon solving even in the slightest detail our race problem in this country – it has come out I think agreeably and it’s good that it was done – I’m glad I did it – but I don’t know how to go into the matter to discuss it with any fairness at all – there were many questions involved there, in the solution of it and its a very long story – I think that the negro in baseball has come into a prominent place in the life of baseball in this country and I don’t believe that there will be any League in the United States that will not be willing to employ negro players within the next year or so – I look for a complete break of the color line in the Southern Association in the year 1956.

…

Davis: Well, it was a great thing for you that Robinson turned out to be a great player, don’t you think?

Rickey: I was very positive about that before I employed him – that I had to be sure about –

Davis: It could have resulted disastrously

Rickey: It was a wild experiment – playing for publicity – I didn’t want that – I can not say that deeply down and indirectly I had in mind the overall effect of the employment of a negro – I was not out primarily to solve the race question in America – I felt that it did have a direct impact upon it – and that it would be healthy and particularly so if Robinson vindicated his choice and he did

Davis: Well long before you ever heard of Robinson you had this feeling

Rickey: Yes, I did indeed – very deeply

Davis: If a negro could play Major League baseball – he should play

Rickey: The utter injustice of it always was in my mind – in St. Louis a negro was not permitted to buy his way into the Grandstand – you know that – and it has only been in recent years that he has been permitted to go into the Grandstand and of course there was no negro player in baseball – I felt very deeply about that thing all my life and within a month after I went to Brooklyn I want to Mr. George McLaughlin and had a talk with him about and found he was sympathetic with my views about it

Davis: He was the Vice President of the Brooklyn Trust Co.

Rickey: He was – and we owed him over $800,000 – the Club did – when I went to Brooklyn and he was a man of wide importance in that community as well as a financier of note – he was President of the Brooklyn Trust Co.

Davis: He gave you support on Robinson?

Rickey: He did – he certainly did – and then my Board did it – they supported me royally on it.

On January 20, 1956, Ricky gave his “One Hundred Percent Wrong Club” speech in Atlanta, Georgia. Some of his address contains echoes of a Montefiore’s letter to British Prime Minster Benjamin Disraeli on the matter of Britain’s Jews and their perceived need to work especially hard and behave extremely well: “Our race can do anything but fail.”

“Now I could talk at some length, of course, about the problem of hiring a negro ball player after an experience of 25 years in St. Louis – where at the end I had no stock at all in the club and no negro was permitted to buy his way into the grandstand during that entire period of my residence in St. Louis. The only place a negro could witness a ball game in St. Louis was to buy his way into the bleachers.. the pavilion. With an experience of that kind in back of me, and having had sort of a “bringins up” that was a bit contrary to that regime in St. Louis.. I went to Brooklyn.

“Within the first month in Brooklyn, I approached what I considered the number one problem in the hiring of a negro in professional baseball in this country. Now that is a story and that could be a fairly long speech. Namely, ownership. Ownership must be in line with you, and I was at that time an employee, not at that time a part owner of the club..

“The second thing was to find the right man as a player. I spent $25,000 in all the Caribbean countries – in Puerto Rico, Cuba – employed two scouts, one for an entire year in Mexico, to find that the greatest negro players were in our own country.

“Then I had to get the right man off the field. I couldn’t come with a man to break down a tradition that had in it centered and concentrated all the prejudices of a great many people north and south unless he was good. He must justify himself upon the positive principle of merit. He must be a great player. I must not risk an excuse of trying to do something in the sociological field, or in the race field, just because of sort of a “holier than thou.” I must be sure that the man was good on the field, but more dangerous to me, at that time, and even now, is the wrong man off the field. It didn’t matter to me so much in choosing a man off the field that he was temperamental – righteously subject to resentments. I wanted a man of exceptional intelligence, a man who was able to grasp and control the responsibilities of himself to his race and could carry that load. That was the greatest danger point of all. Really greater than the number five in the whole six.

“Number one was ownership, number two is the man on the field, number three the man off the field. And number four was my public relations, transportation, housing, accommodations here, embarrassments – feasibility. That required investigation and therein lies the speech. And the Cradle of Liberty in America was the last place to make and to give us generous considerations.

“And the fifth one was the negro race itself – over-adulation, mass attendance, dinners, of one kind or another of such a public nature that it would have a tendency to create a solidification of the antagonisms and misunderstandings – over-doing it..

“But the greatest danger, the greatest hazard, I felt was the negro race itself. Not people of this crowd any more than you would find antagonisms organized in a white crowd of this caliber either. Those of less understanding – those of a lower grade of education frankly. And that job was done beautifully under the leadership of a fine judge in New York who became a Chairman of an Executive Committee. That story has never been told. The meetings we had, two years of investigations – the Presidents of two of the negro colleges, the publisher of the Pittsburgh Courier, a very helpful gentleman he was to me, a professor of sociology in New York University, and a number of others, the LaGuardia Committee on Anti-Discrimination, Tom Dewey’s Committee in support of the Quinn-Ives Law in New York state.

“And sixth was the acceptance by his colleagues, his fellow players. And that one I could not handle in advance. The other five over a period of two and one-half years, I worked very hard on it. I felt that the time was ripe, that there wouldn’t be any reaction on the part of a great public if a man had superior skill, if he had intelligence and character and had patience and forbearance, and “could take it” as it was said here. I didn’t make a mistake there. I have made mistakes, lots of mistakes.

“A man of exceptional courage, and exceptional intelligence, a man of basically fine character, and he can thank his forbearers for a lot of it. He comes from the right sort of home, and I knew all this, and when somebody, somewhere, thinks in terms of a local athletic club not playing some other club because of the presence on the squad of a man of color. I am thinking that if an exhibition game were to be played in these parts against a team on whose squad was Jackie Robinson – even leaving out all of the principle of fair play, all the elements of equality and citizenship, all the economic necessities connected with it, all the violations of the whole form and conceptions of our Government from its beginning up to now – leave it all out of the picture, he would be depriving some of the citizens of his own community, some wonderful boys, from seeing an exhibition of skill and technique, and the great, beautiful, graciousness of a slide, the like of which they could not see from any other man in this country. And that’s not fair to a local constituency.

“I am wondering, I am compelled to wonder, how it can be. And at the breakfast, recently, when a morning paper’s story was being discussed and my flaxen hair daughter said to me, “He surely didn’t say it.” I thought, yes it is understandable. It is understandable. And when a great United States Senator said to me some few days after that, “Do you know that the headlines in Egypt are terribly embarrassing to our State Department?” And then he told me, in part, a story whose utter truthfulness I have no reason to doubt, about the tremendous humiliation – “The Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave,” – “where we are talking about extending to all civilizations, tremendous and beautiful freedoms, and the unavoidable, hypocritical position it puts us in internationally,” “How could anybody do it,” said my daughter.turned with the body control that’s almost inconceivable and cut off the runner at second base on a force play. I took Clay and I put my hand on his shoulder and I said, “Did you ever see a play to beat it?”

Acceptance was not instant.

“Now this fellow comes from Greenwood, Mississippi. And he would forgive me, I am sure, because of the magnificent way that he came through on it. He took me and shook me and his face that far from me and he said, ‘Do you really think that a ni**er is a human being, Mr. Rickey?’ That’s what he said.”

Rickey saw in baseball a sign of social change:

“I am completely color-blind. I know that America is – it’s been proven Jackie – is more interested in the grace of a man’s swing, in the dexterity of his cutting a base, and his speed afoot, in his scientific body control, in his excellence as a competitor on the field – America, wide and broad, and in Atlanta, and in Georgia, will become instantly more interested in those marvelous, beautiful qualities than they are in the pigmentation of a man’s skin, or indeed in the last syllable of his name. Men are coming to be regarded of value based upon their merits, and God hasten the day when Governors of our States will become sufficiently educated that they will respond to those views.”

Elevated and empowered, Robinson rose to the task.

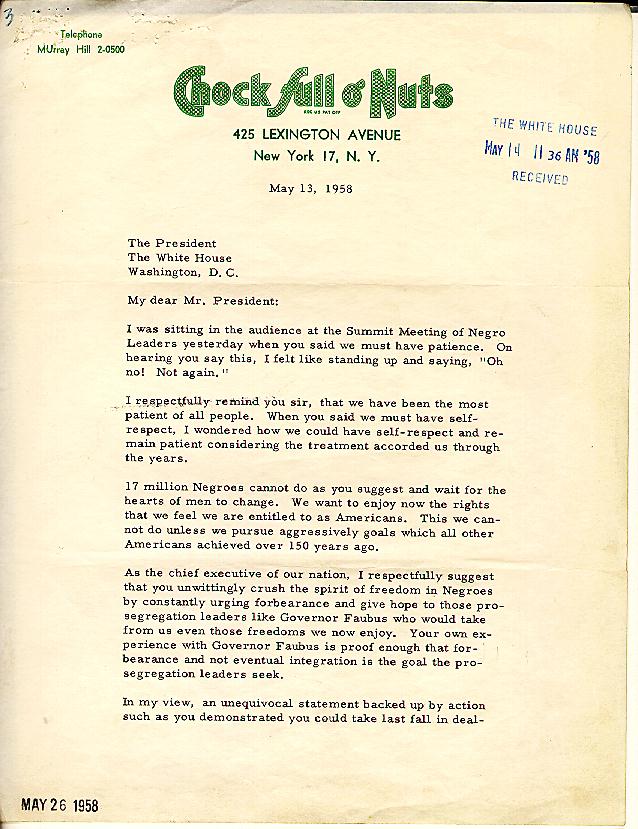

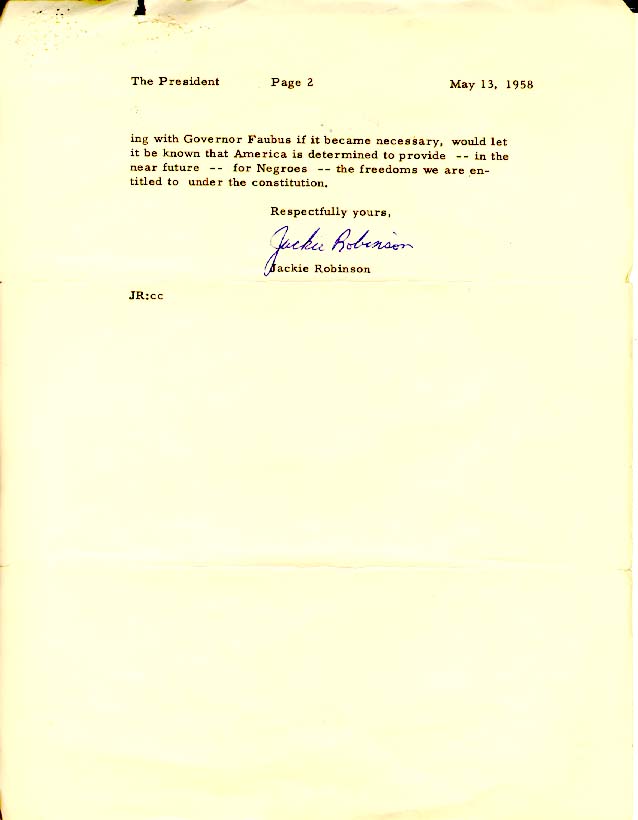

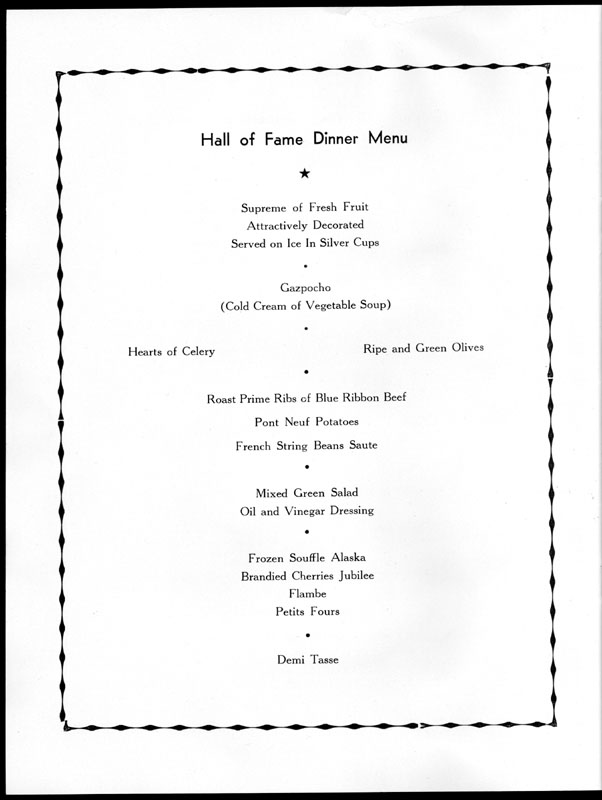

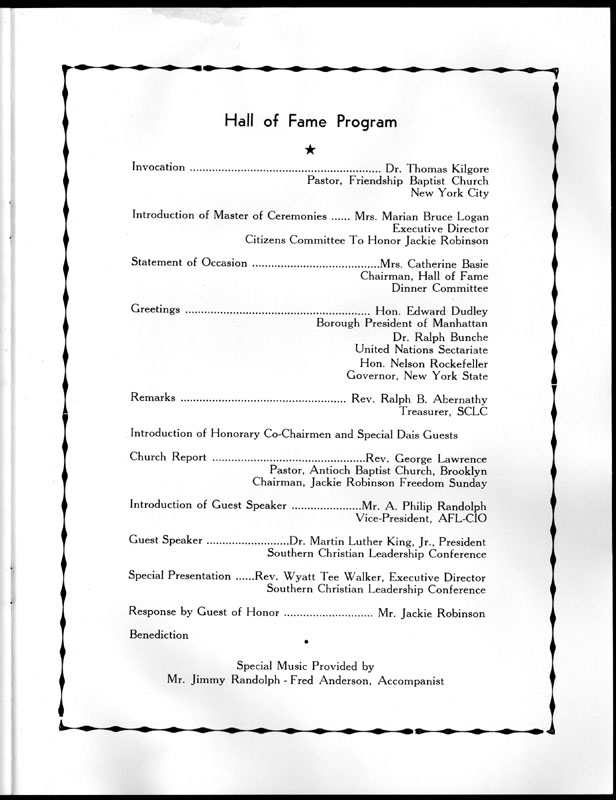

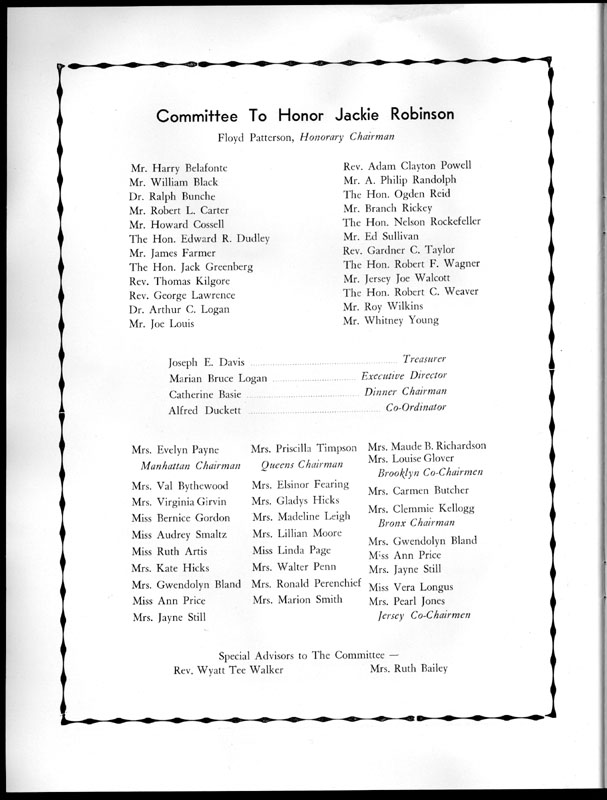

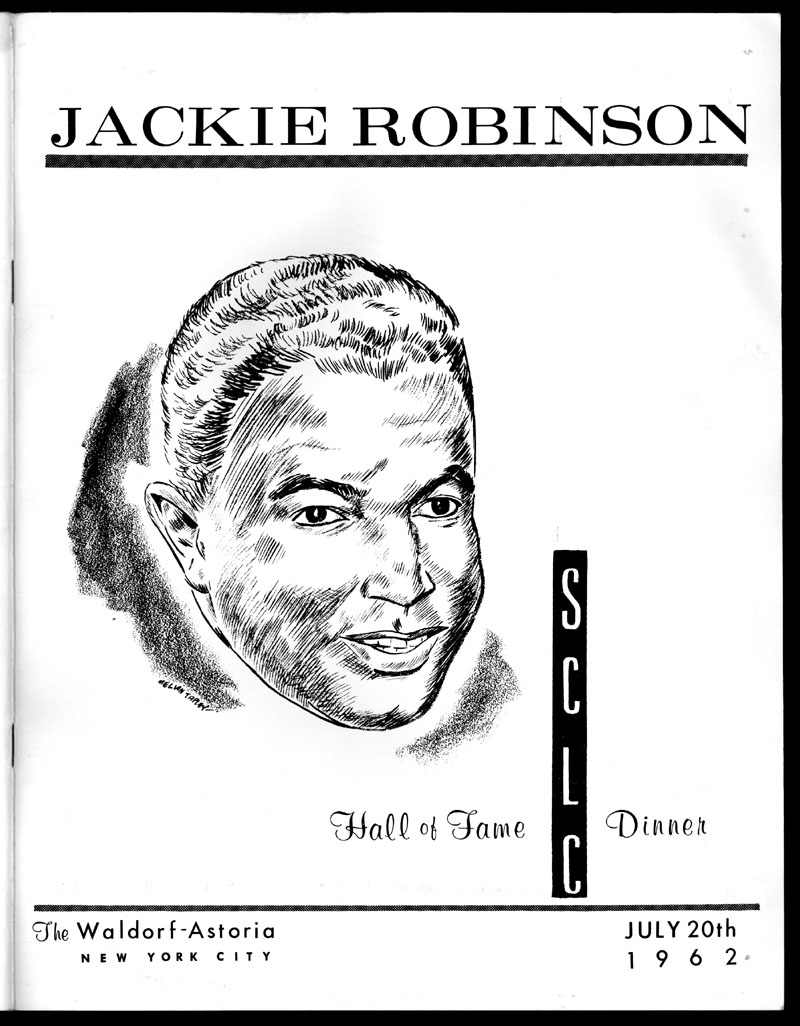

Cover and selected pages from program for Southern Christian Leadership Conference Hall of Fame dinner honoring Jackie Robinson, July 20, 1962, Waldorf-Astoria, New York City.

The Baseball Hall of Fame pays tribute to Robinson:

Robinson joined the Montreal Royals, the Dodgers top farm team, in 1946 and led the International League with a .349 average and 40 stolen bases. He earned a promotion to the Dodgers and made his major league debut on April 15, 1947.

“It was the most eagerly anticipated debut in the annals of the national pastime,” authors Robert Lipsyte and Pete Levine wrote. “It represented both the dream and the fear of equal opportunity, and it would change forever the complexion of the game and the attitudes of Americans.”

At the end of his first season, Robinson was named the Rookie of the Year. He was named the NL MVP just two years later in 1949, when he led the league in hitting with a .342 average and steals with 37, while also notching a career-high 124 RBI. The Dodgers won six pennants in Robinson’s 10 seasons, but his contributions clearly extended far beyond the field.

You can do whatever you like when you’re one of the emancipated untermensch – but when you play the bad hand dealt you don’t you date fail.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.