AND now for our supporting feature…

AND now for our supporting feature…

I have happy memories of Birmingham, where he lived for a while in the 1980s. He remembers particularly fondly the friendly people and the dry sense of humour, as epitomised by the smutty and amusing ads for the local beer.

His memories of other aspects of Brum are less fond, however. He was left cold by New Street Station, and even colder by the Bull Ring – a sixties concrete shopping centre full of run-down market stalls, with a noisy motorway overhead.

Others begged to differ, though.

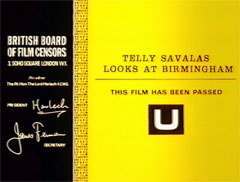

Take Telly Savalas, to pick a name at random. In the early 1980, the suave star of Kojak was such a big fan of the Midlands metropolis that he narrated Telly Savalas Looks At Birmingham. He called it ‘my kinda town’ and he didn’t stint on the praise.

Traffic was never a problem for Telly. How could it be? After all, the West Midlands Traffic Police HQ was home to “one of the most specialised traffic control groups in the world”.

Telly loved everything about Birmingham. “This is the view that nearly took my breath away,” he says, as the camera pans out to reveal several square miles of concrete high-rises. “I found the city exciting,” he enthuses, over more shots of arterial roads. “You feel as if you’ve been projected into the twenty-first century.”

Birmingham is “the nation’s industrial powerhouse,” he notes approvingly – even its museum and art gallery are ‘powerhouses of treasure”.

Birmingham is “the nation’s industrial powerhouse,” he notes approvingly – even its museum and art gallery are ‘powerhouses of treasure”.

But it wasn’t all power and thrust. He found time to admire “the trees and shrubs in the spacious traffic-free pedestrian precincts” (four pots in front of Dixons) and visit one of the city’s parks. Here he stumbled upon an open-air over-forties disco competition (“incredible!”) in which elderly men shuffled back and forth and ladies flashed their ample underwear. (“This is Mrs Taylor… I’m sure somebody loves ya, baby…”)

Not that Birmingham was the only place to float Telly’s boat. Telly Savalas Looks At Aberdeen and Telly Savalas Looks At Portsmouth were similarly upbeat. “I’m crazy about castles,” he says at one poetic point. “I suppose this could be called a castle. It’s the polytechnic – a castle of learning.”

“I was captivated by everything I saw,” he says of Aberdeen, after a tour of the coach station and oil-rigs, “and I’ll be back, that’s for sure.”

Unlikely. In fact, as you might have guessed, he didn’t actually visit any of the places whose virtues he extolled so eloquently. Chances are he had never heard of them until his London agent struck a deal with a man called Harold Baim.

Baim was a prolific director of ‘quota quickies’, the support features that were still a familiar part of the British cinema experience in the era of yuppies and giant mobile phones.

Their name came from the quota rule, an ancient agreement that obliged American distributors to sponsor British films in exchange for getting their own flashy Hollywood efforts shown in our picture houses.

Some were dramas, in the best traditions of the American B-movies, but most were documentaries and travelogues, usually with cheesy scripts and even cheesier soundtracks compiled from stock library music – Hammond organ a speciality.

Some were dramas, in the best traditions of the American B-movies, but most were documentaries and travelogues, usually with cheesy scripts and even cheesier soundtracks compiled from stock library music – Hammond organ a speciality.

Baim was the king of the quota quickie (his other claim to fame was discovering Michael Winner). His trademark travelogues featured sunny skies, alluring alliteration, and narrators of the standing of Terry Wogan and Nicholas Parsons. He is remembered today mainly thanks to the tireless work of Richard Jeffs and the Baim Collection.

For more Baim visit www.baimfilms.com

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.