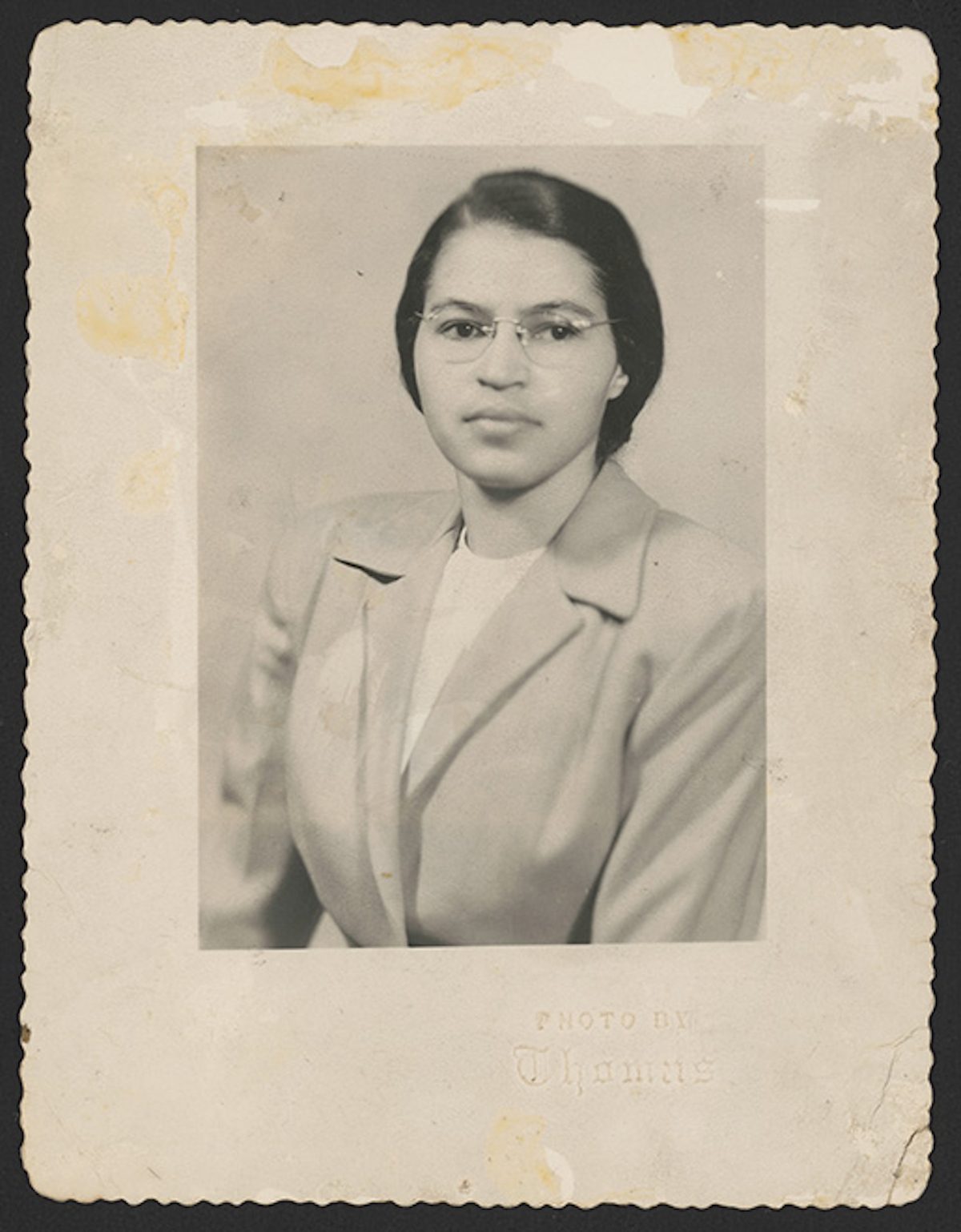

Rosa Parks circa 1950

“Our non-violent protest has proven to all that no intelligent right-thinking person is satisfied with less than human rights that are enjoyed by all people.”

Every once in a while, one hears a right-wing demagogue in the U.S. compare themselves to Rosa Parks in defense of an unpopular position. Not only is this insulting on its face for the blatant disrespect of a Civil Rights hero, but it is also indicative of how little most Americans actually know about Parks’ life and work.

Known to schoolchildren everywhere as the “brave lady who wouldn’t give up her seat,” few are aware that Parks began her activist career over 20 years before her refusal in 1955 sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which itself helped spark the nationwide Civil Rights movement. (Also, note that Parks was not the first to refuse to move: the honor belongs to then-15-year-old Claudette Colvin.)

Parks’ first high profile fight against racism in the South came when she and her husband, Raymond, began organizing in support of the “Scottsboro Boys,” nine African American teenagers and young men falsely charged and convicted of raping two white women in 1931. The case rose to national prominence and inspired artists from Woody Guthrie to Lead Belly to Harper Lee, who based To Kill a Mockingbird on the injustice.

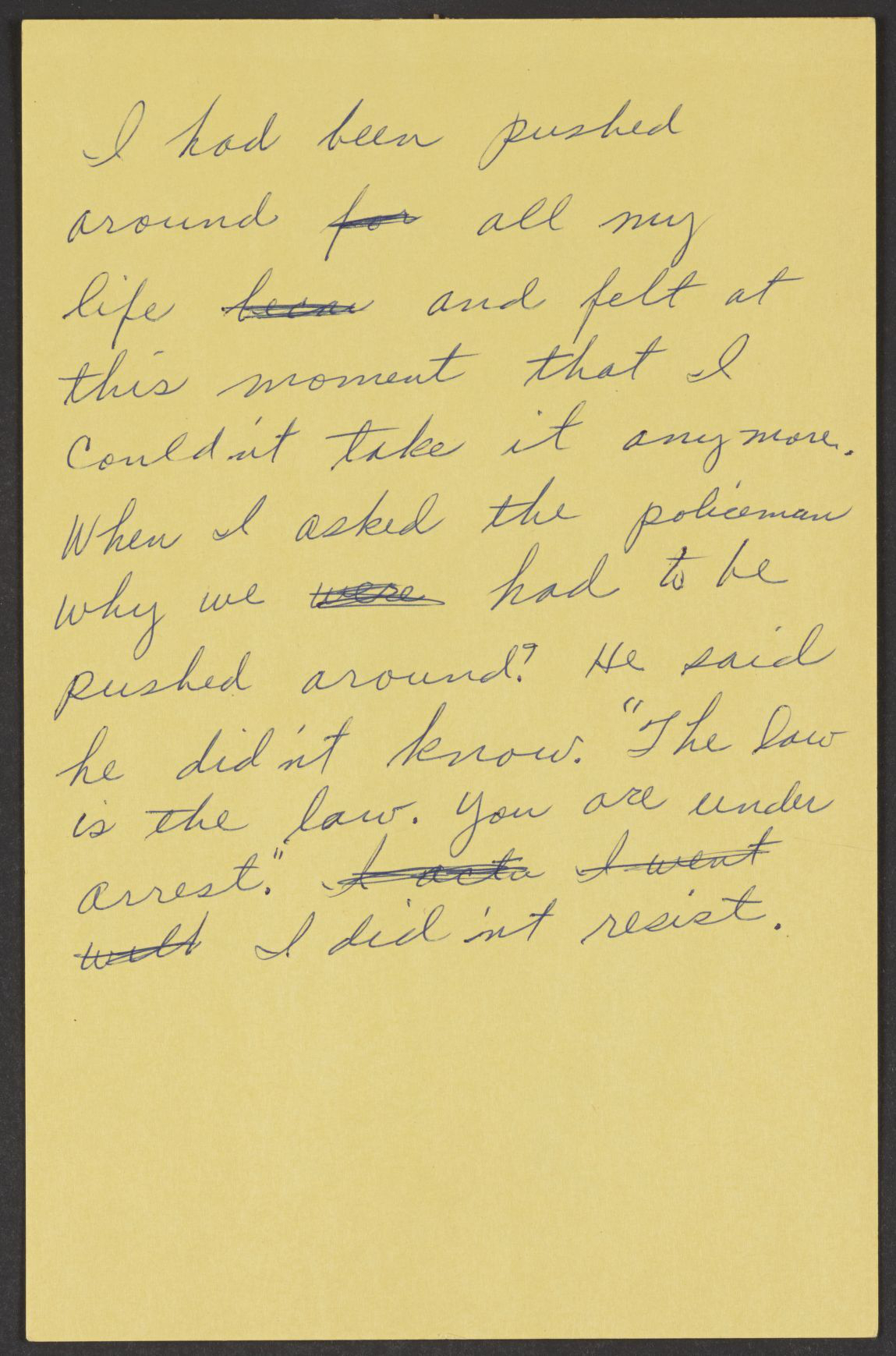

Draft of a speech in support of the Montgomery Bus Boycott

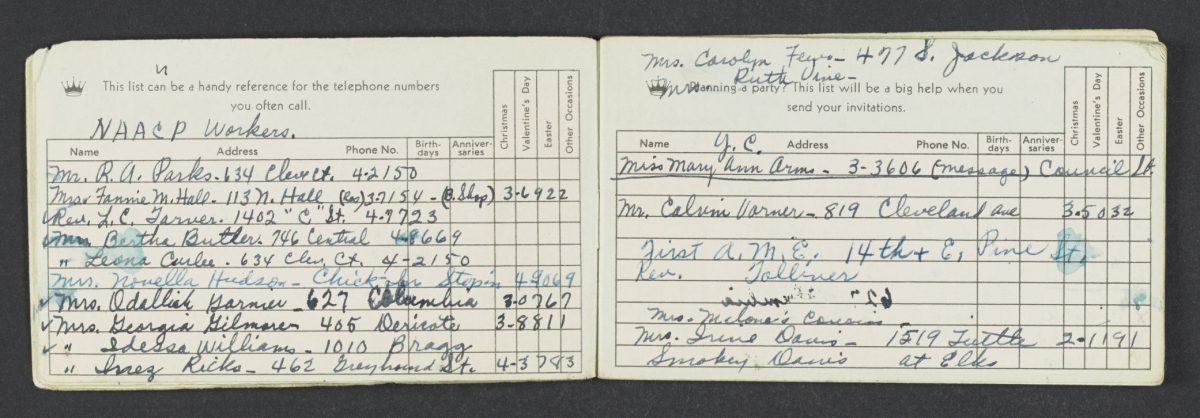

Parks’ early writings show her determination, in her own words, to “never to accept [Jim Crow], even if it must be endured.” She became secretary of the Montgomery NAACP in 1943 and continued in the role for the next 10 years, “working for freedom and first class citizenship,” she wrote, in the fights for voter rights, school desegregation, and “legal remedies for black victims of white brutality and sexual violence,” as Parks’ biographer Jeanne Theoharris writes in an essay for the Library of Congress Magazine.

As part of that struggle, she became the lead investigator on the case of Recy Taylor, a black woman raped by a gang of white men in 1944. Although the accused were brought before two grand juries after authorities faced considerable outside pressure, they were never formally charged or convicted of the crime. (One man even confessed to the crime, but insisted the attack was “consensual.”) Parks continued her work, yet “after years of such efforts, she grew increasingly discouraged by the lack of change.”

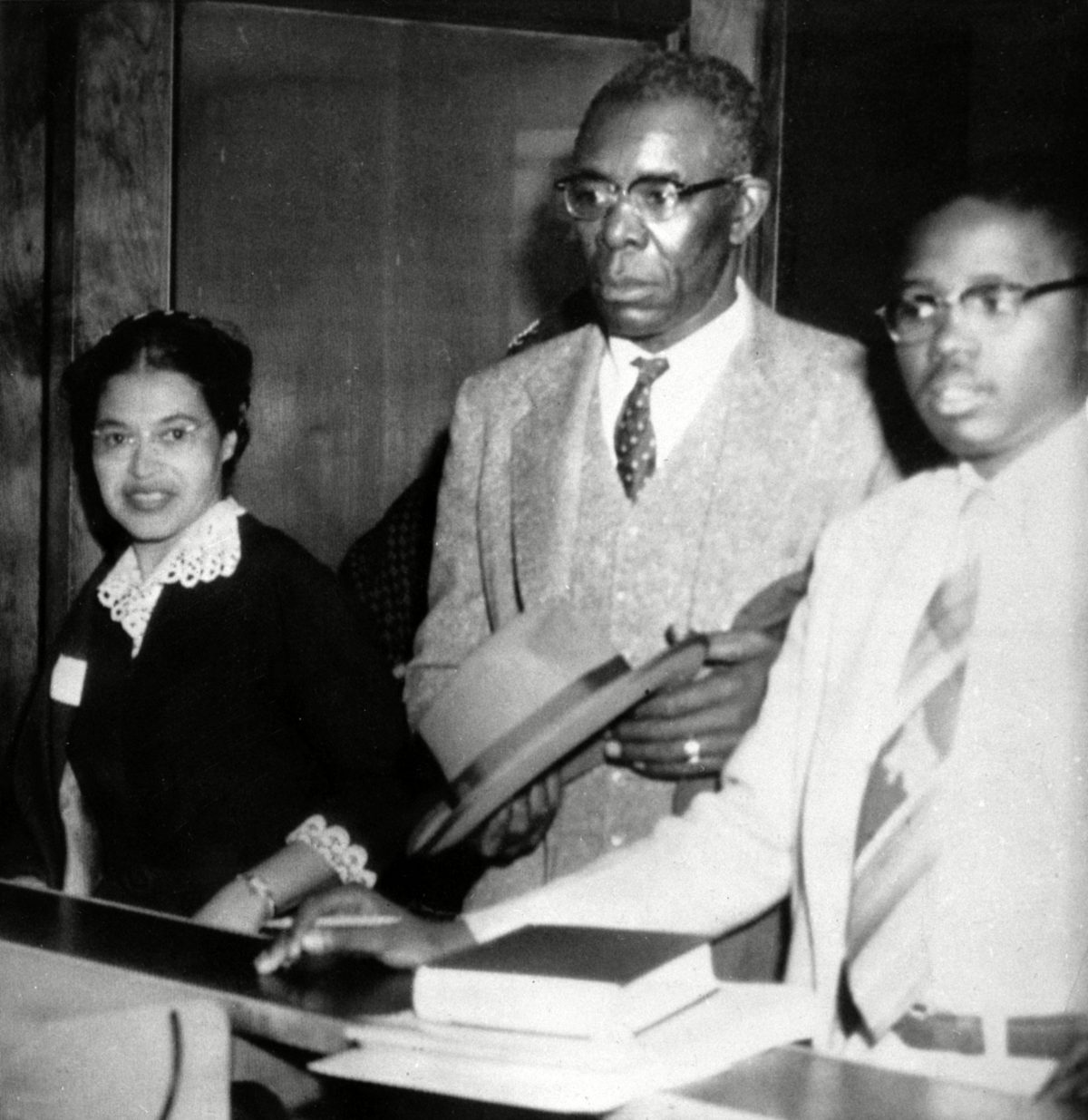

Thurgood Marshall, the Chief Counsel for the NAACP with Rosa Parks in 1956. Parks joined the Montgomery, Alabama chapter of the NAACP in 1943 and was the chapters secretary in 1956.

In August of 1955, Parks traveled to the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, a still-active training ground for organizers and activists (set on fire just last year by white nationalists). There, she studied under Septima Clark (above, left), founder of the school’s Citizenship program, which organized for literacy and voting rights.

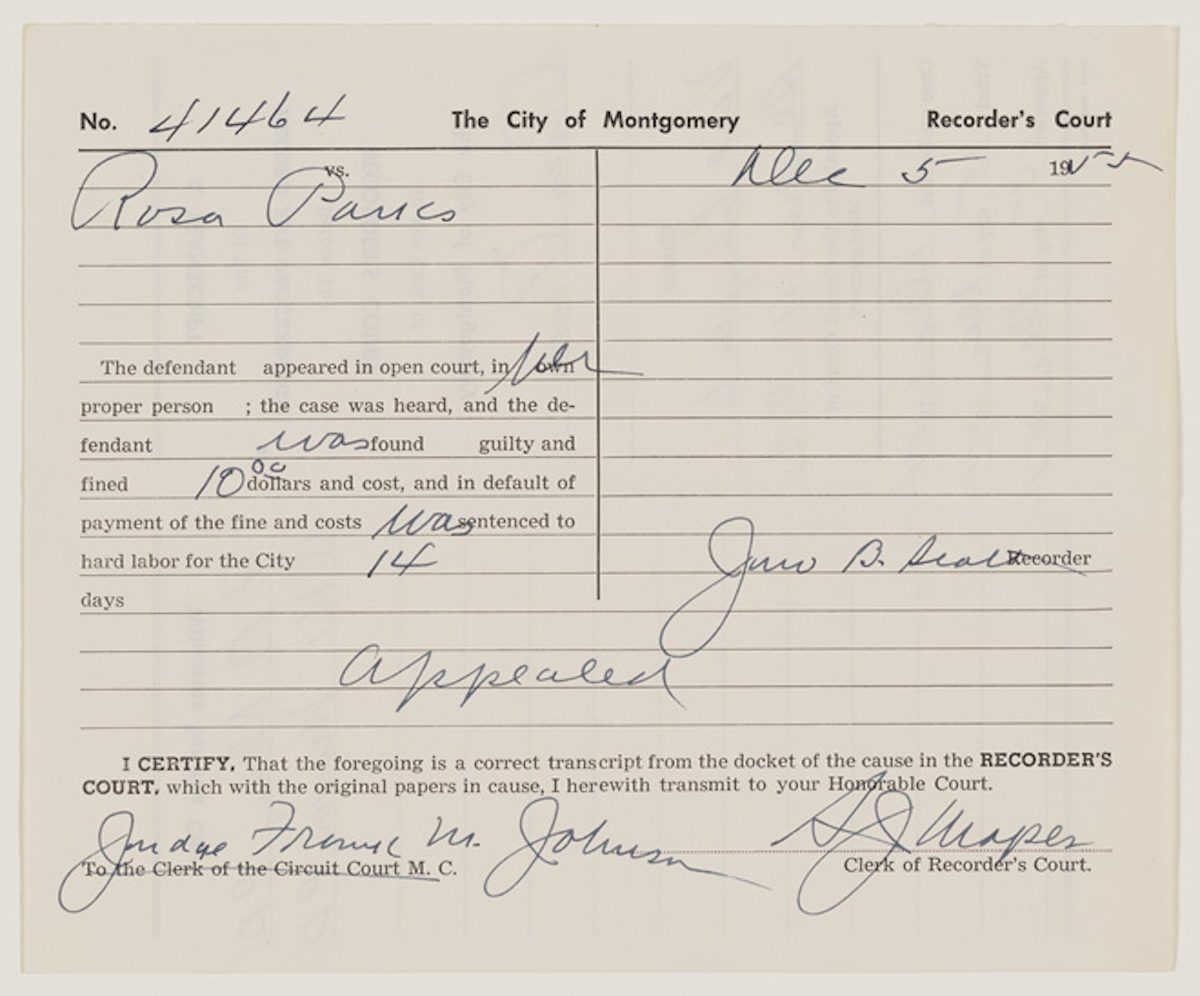

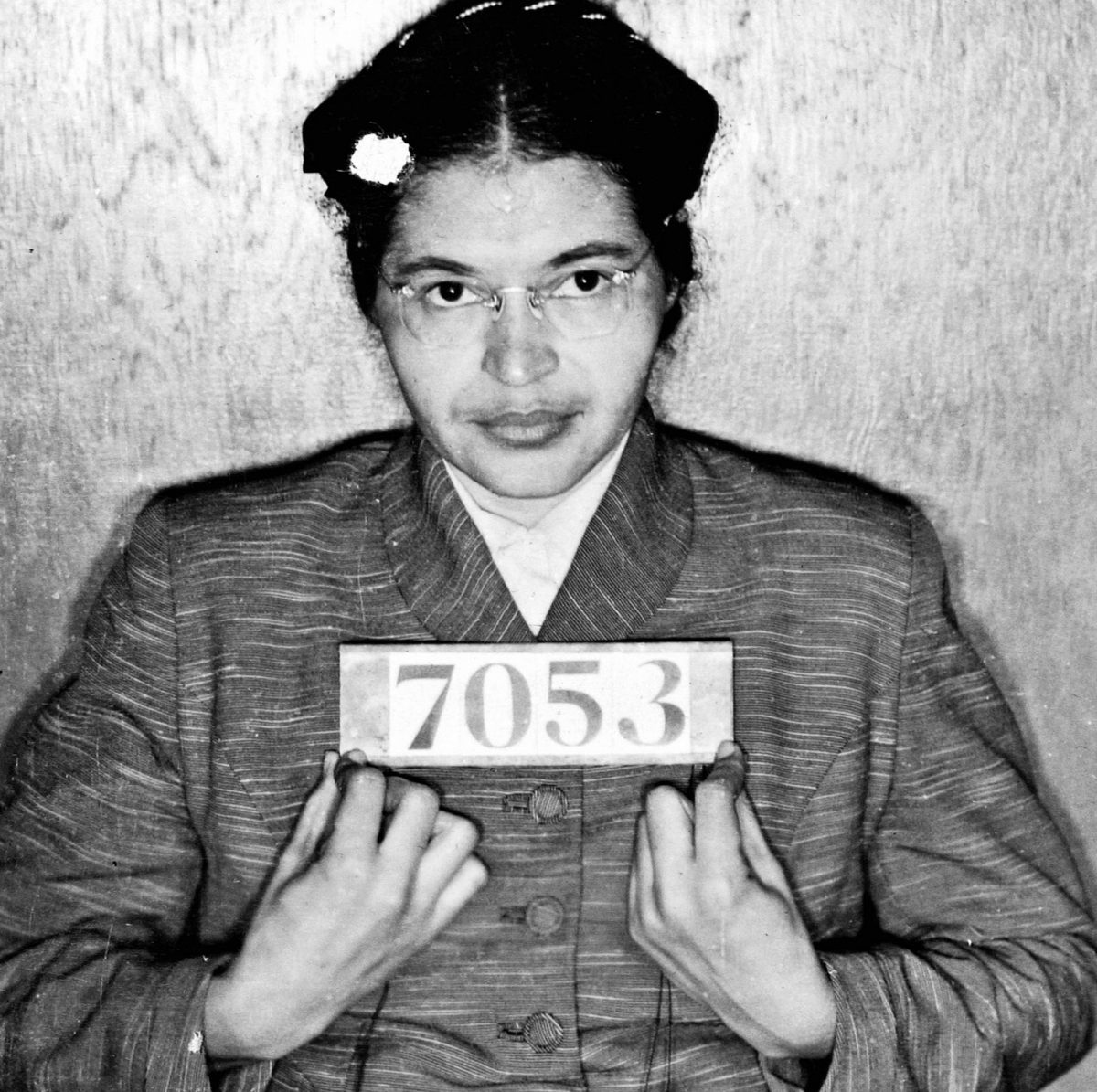

Rosa Parks Rosa Parks, left, who was fined $10 and court costs for violating Montgomery’s segregation ordinance for city buses, makes bond for appeal to Circuit Court. Signing the bond were E.D. Nixon, center, former state president of the NAACP, and attorney Fred Gray. Parks’ arrest for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on Dec. 1, 1955 touched off the Montgomery bus boycott. Her act of civil disobedience got relatively little attention, noted briefly in The Montgomery Advertiser. The story went national Dec. 5, 1955, when the AP wrote of a plan to make Parks the test case for laws segregating public transportation.

Rosa Parks’ arrest report, December 5, 1955

“The workshop buoyed her spirit,” and she returned to Montgomery with renewed energy, enough to take on the segregated bus companies in Alabama with her planned protest in December of 1955. She knew she might “be manhandled,” she said of the refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger, “but I was willing to take the chance… I suppose when you live this experience… getting arrested doesn’t seem so bad.”

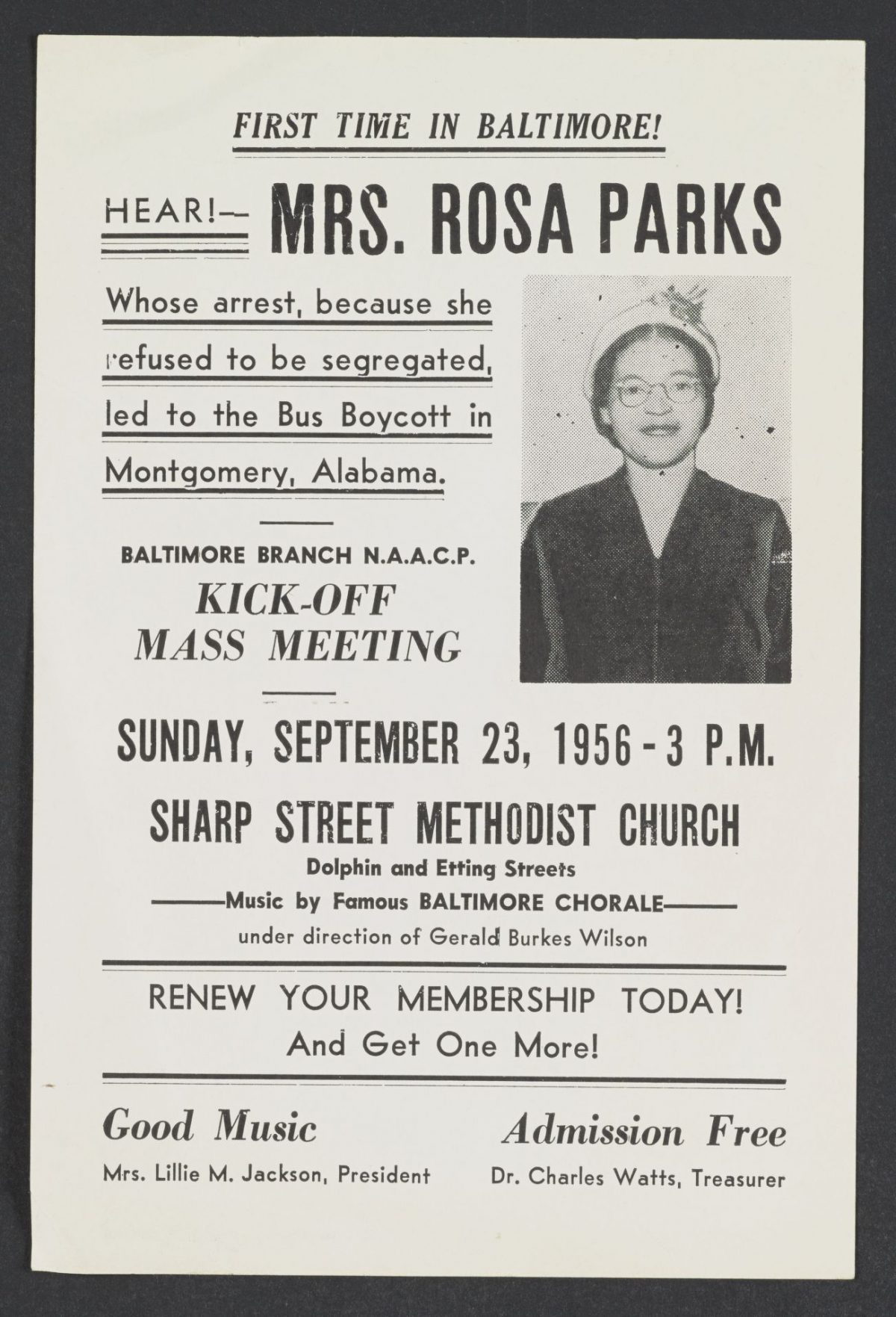

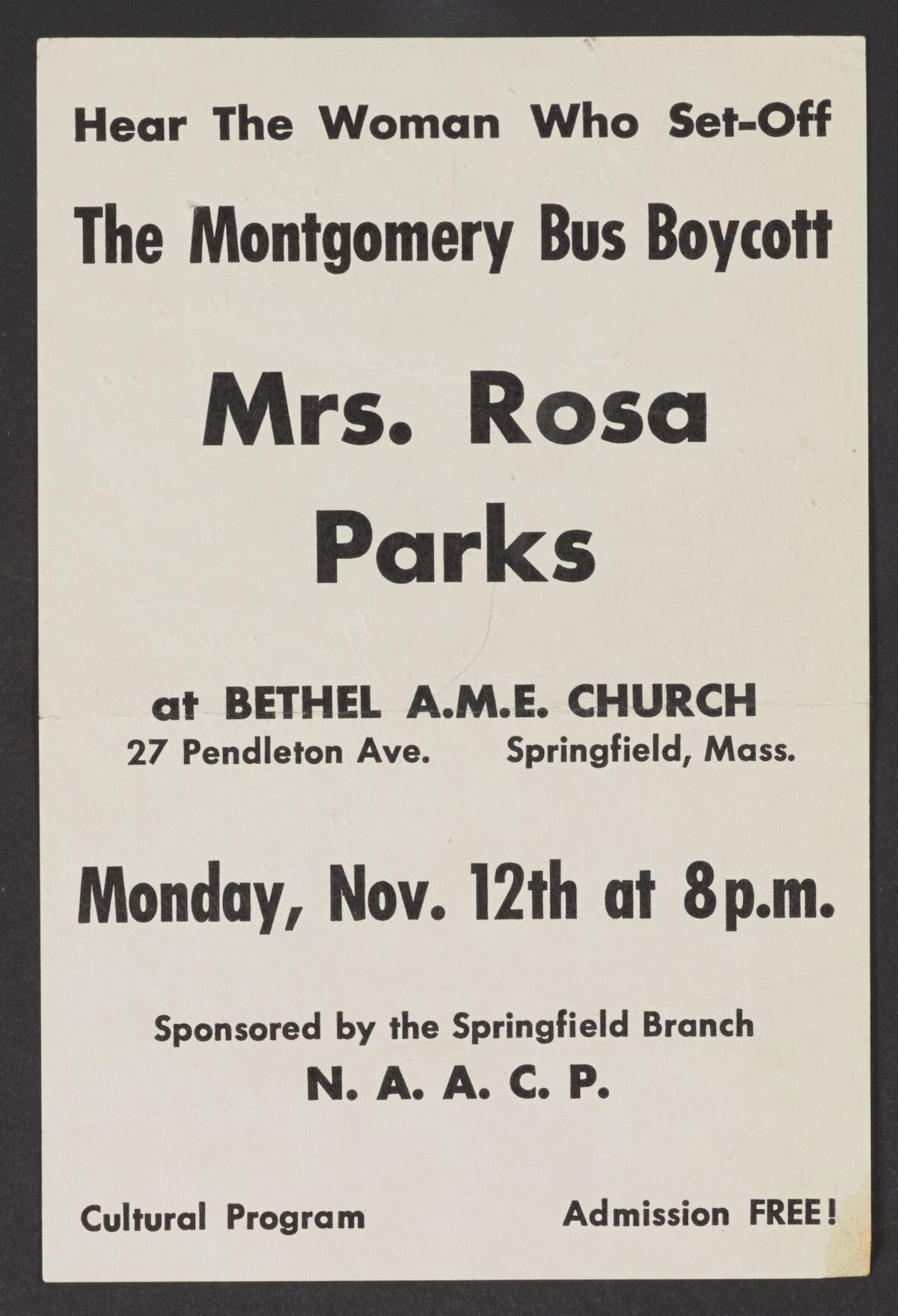

After the boycott began, Parks continued to organize, serving as a carpool dispatcher for a month (see her dispatch notebook above). She also worked “to sustain the protest… exhorting riders and drivers to keep going,” Theoharris writes. “In her detailed instructions to carpool riders and drivers, she wrote, ‘Remember how long some of us had to wait when the buses passed us without stopping in the morning and evening.” She traveled to raise money and awareness, giving speeches nationwide.

The protest took a heavy toll on the working-class Parks family. Rosa was fired from her job as a tailor’s assistant at the Montgomery Fair department story a month into the boycott, and soon after, Raymond lost his position as a barber at Maxwell Air Force Base. The couple relocated to Detroit and continued to face serious hard times financially, prompting Jet magazine to run a 1960 story on “the troubles of the boycott heroine.”

The price Parks paid for her lifetime of activism was reflected in the recent fate of her Detroit home, scheduled to be demolished until her niece purchased the house for $500. In 2018, a Berlin-based American artist, Ryan Mendoza bought the house and had it relocated to Germany. Mendoza hoped to preserve the house until it could be sold and cared for by a U.S. institution, but so far no one in the U.S. has been willing to claim and care for this symbol of Parks’ legacy.

(All images except the Rosa Parks’ House from the Library of Congress exhibit Rosa Parks in Her Own Words)

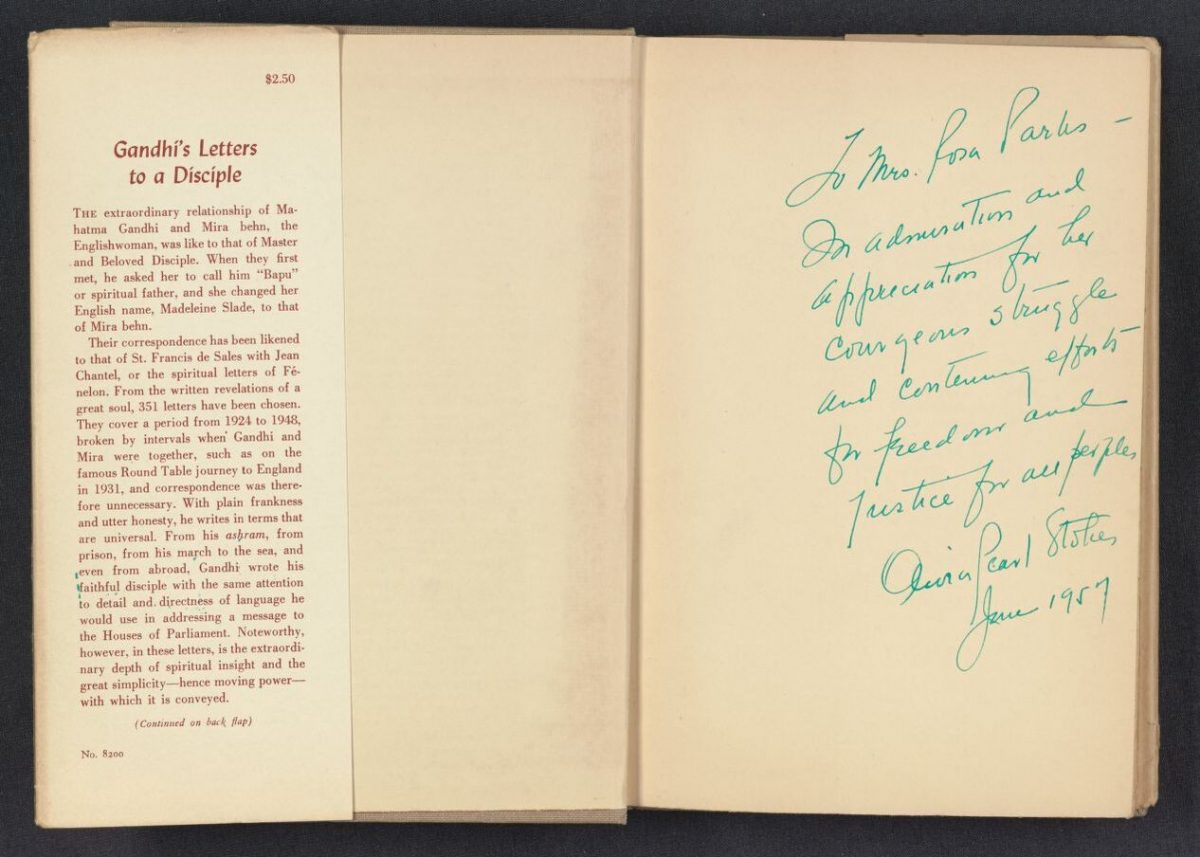

Rosa Parks copy of Gandhi’s Letters to a Disciple, inscribed to her by Baptist minister, educator, and activist Olivia Pearl Stokes

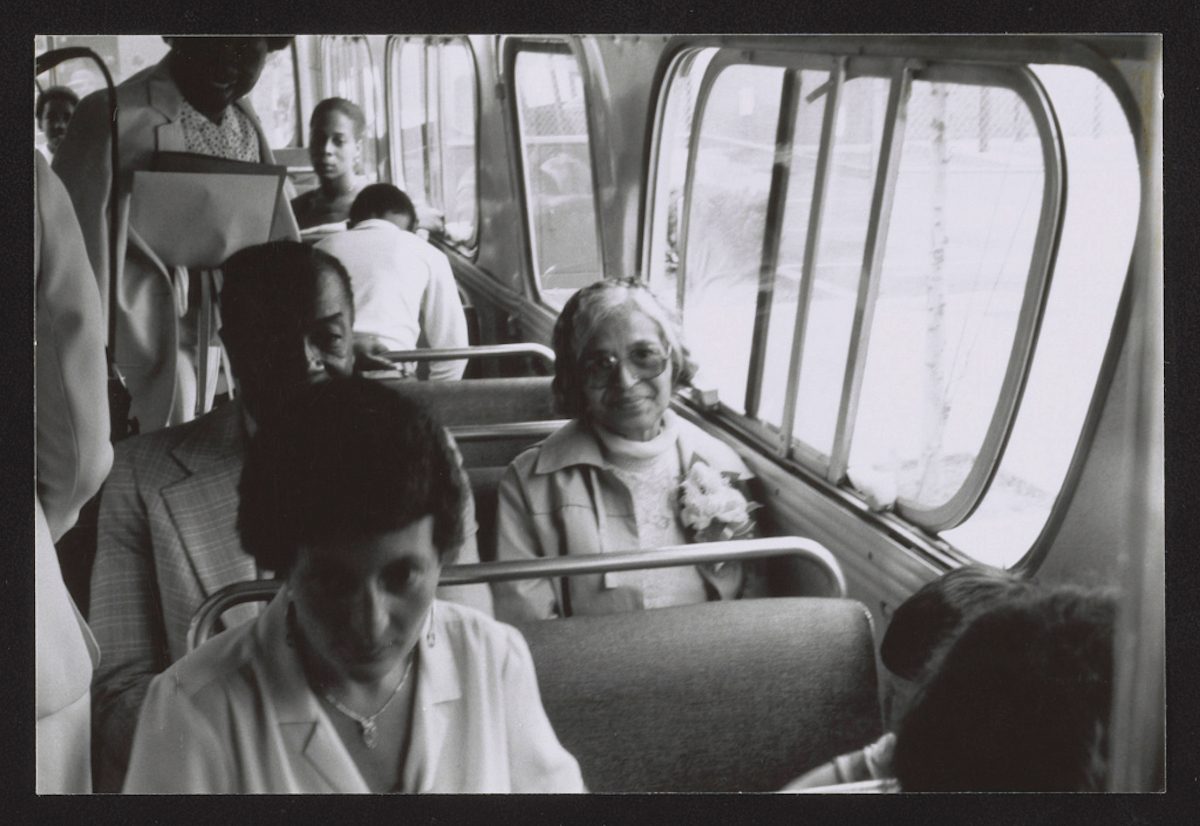

Rosa Parks on a public bus in Detroit, 1995

</p

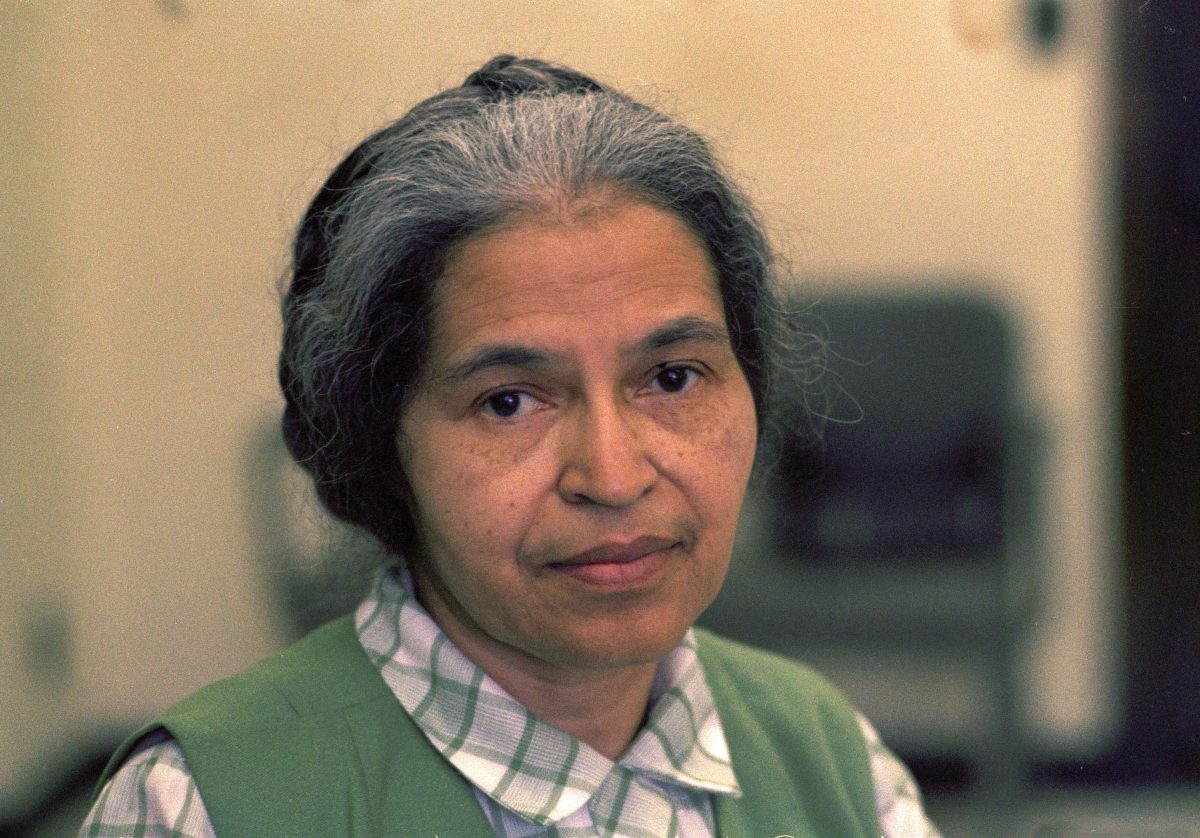

Parks Rosa Parks – Detroit – 1 May 1971

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.