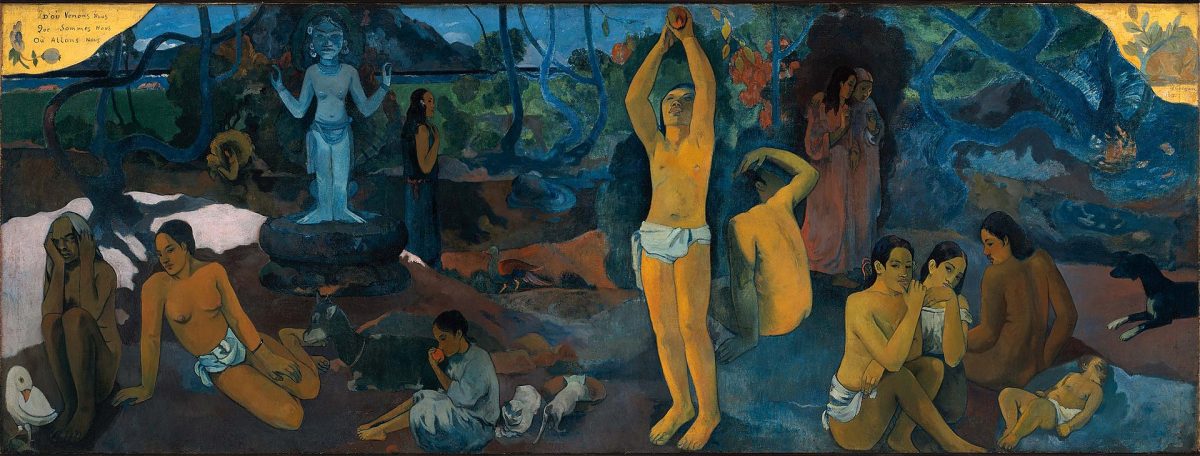

There is something about Anita Rée‘s life and work which makes me think of Paul Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Not so much the painting itself but the title which describes Rée’s life looking for who she was and where she came from and what this meant. Rée spent her life following different artistic movements, developing different styles, seeking the best way to express herself as an artist. But at the very moment Rée reached this point, she was outed as a Jew and her worked denounced as “degenerate” by the Nazis.

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

French: D’où venons-nous ? Que sommes-nous ? Où allons-nous? by Paul Gauguin, 1897-1898

Anita Rée was born on the 9th of February 1885 in Hamburg to a Jewish father and Catholic mother. Anita and her sister Emilie were baptised and raised as Lutherans, which may seem strange to us today but this was an accepted norm for upper middle and upper class Jewish people at the time who were wary to assimilate into the German social order.

In 1905, at age of twenty, Rée studied art with the German Impressionist painter Arthur Siebelist. This was a daring break from the ambitions of her parents who thought Rée, like her sister Emilie, should marry into an established family and raise a brood of children, thus progressing the family’s standing in society. Rée wanted none of this.

In 1906, Rée met the German Jewish artist Max Liebermann. He recognised her talent and encouraged her to develop her own style. Rée studied under Liebermann for almost five years before forming an artist’s commune in Hamburg with Franz Nölken. This did not last long due to Rée’s unrequited love for Nölken. Heartbroken, Rée fled to Paris where she studied under Fernand Léger.

In Paris, Rée met and mixed with the likes of Picasso, Matisse, and the Jewish-Catholic poet Max Jacob. In 1913, Rée exhibited in Hamburg, then returned to the city, establishing herself as a portrait artist. Portrait painting paid for a roof over her head and put food on the table but did not fulfil Rée’s artistic ambitions. By 1919, she had joined the Hamburg Secession, which like similar movements in Vienna and Berlin rebelled against the traditional paternalism and conservatism of art.

During the early 1920s, Rée moved to Italy, where she lived in Positano. Here she painted landscapes and developed her own distinct style. Though she gained some success, women were not considered “artists” by most of the boys who declared themselves the true “artists”. Women were cast as muses or mother figures – there to supply “the beer and sandwiches.”

To counter this misogyny, Rée returned to Hamburg where she was one of the original members of GEDOK, or the Association of German and Austrian Artists’ Associations of All Art Genres (Gemeinschaft Deutscher und Oesterreichischer Künstlerinnenvereine aller Kunstgattungen), a society to hep and promote the work of women artists established by Ida Dehmel in 1926.

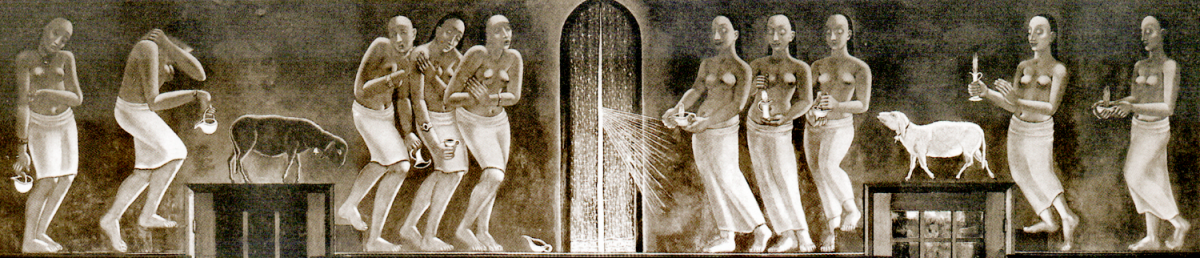

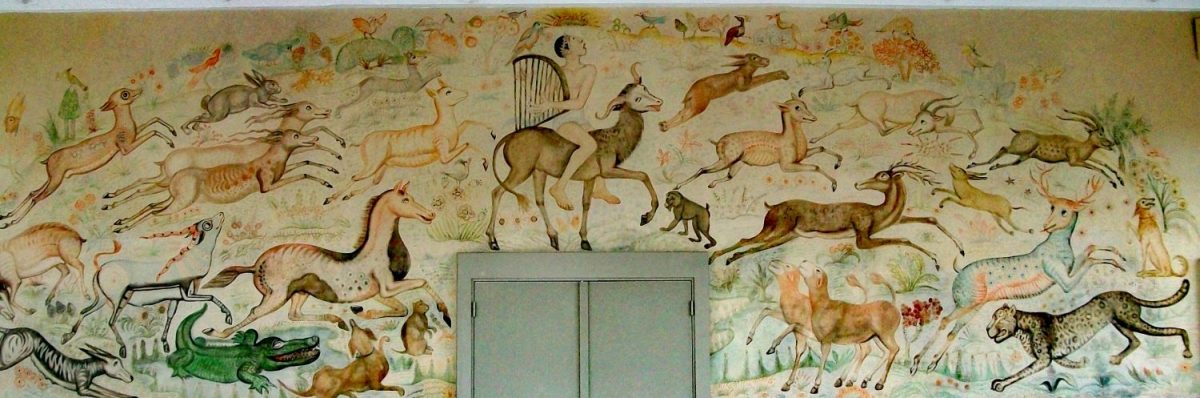

Rée was commissioned to paint several murals in the city – which were later destroyed by the Nazis. In 1930, she was commissioned to create a triptych for the new Ansgarkirche in Langenhorn. When Rée delivered her work in 1932, the Church elders considered it offensive, not suitable, and far too Jewish (as if Jesus was not also ‘too Jewish’). The incident quickly escalated. Rée was reported to the authorities as “a Jew” and denounced by the Hamburg Art Group as an “alien” – someone “foreign to the species”.

This devastated Rée. Aware of the radical and menacing change in Germany under the rise of the Nazis, she fled to the German island of Sylt.

Today Sylt has some of the highest house prices in the world. It is a much sought-after idyll for the rich and famous to own a holiday home. After the Second World War, the former SS commander Heinz Reinefarth moved to the island. He was wanted for trial for the numerous atrocities he had carried out against the Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto. No matter how times Poland demanded Reinefarth’s extradition, the German authorities refused, claiming genocide was not a crime under Nazi German law and therefore such a charge could not be applied retroactively. Reinefarth became the mayor of Westerland on Sylt. In 1962, he was elected to the Parliament of Schleswig-Holstein. Reinefarth, the SS executioner of thousands of Jewish people, also received his General’s pension upon retirement. He died peacefully at the age of 75 in 1979, rich, successful, and content.

It’s interesting to compare the lives and fates of Rée and Reinefarth. Rée escaped to Sylt hunted as a Jew. Reinefarth escaped to Sylt to live freely as a mass murderer and war criminal.

Back on mainland Germany, Rée was listed as a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis. Her work was listed for destruction. Fortunately Wilhelm Werner, a groundskeeper at the Hamburger Kunsthalle, hid many of Rée’s paintings and drawings in the attic of his house.

Meanwhile, Rée began painting and drawing the landscapes on Sylt. She preferred to paint animals and landscapes rather than people. Her life had fallen apart. Rée fell into a deep depression. She questioned who she was, who she thought she was and what she had achieved. No family, no friends, no success. Now branded a degenerate and exiled as a Jew. In a farewell letter to her sister, Rée wrote:

I can no longer find my way in such a world, to which I no longer belong and I have no desire but to leave it. What is the point – without a family, without the once loved art and without any people – to continue to vegetate alone in such an indescribable, madness-riddled world . . . ?

Rée committed suicide on 12th December 1933.

If Anita Rée had been born a man, then she would have been hailed as a pioneering and revolutionary artist. As a woman artist, she was often dismissed and overlooked. As an artist deemed Jewish, her work was denounced as “bastardly” and “degenerate”, and much of her work was destroyed.

Rée was baptised a Lutheran. She was raised a Lutheran in an upwardly mobile middle class German family. This security gave her an opportunity to rebel and study art. She travelled at a time when it was considered immoral for women to travel alone. She lived life by her own rules convinced by her Christian beliefs and middle class values. Then one day, she finds out she is Jewish and is quickly ostracised by the very people, the very society she thought herself a member. Who was she? Where did she come from? Where was she going? These were questions she asked in her art until one day there was no place to go and no more questions to be answered.

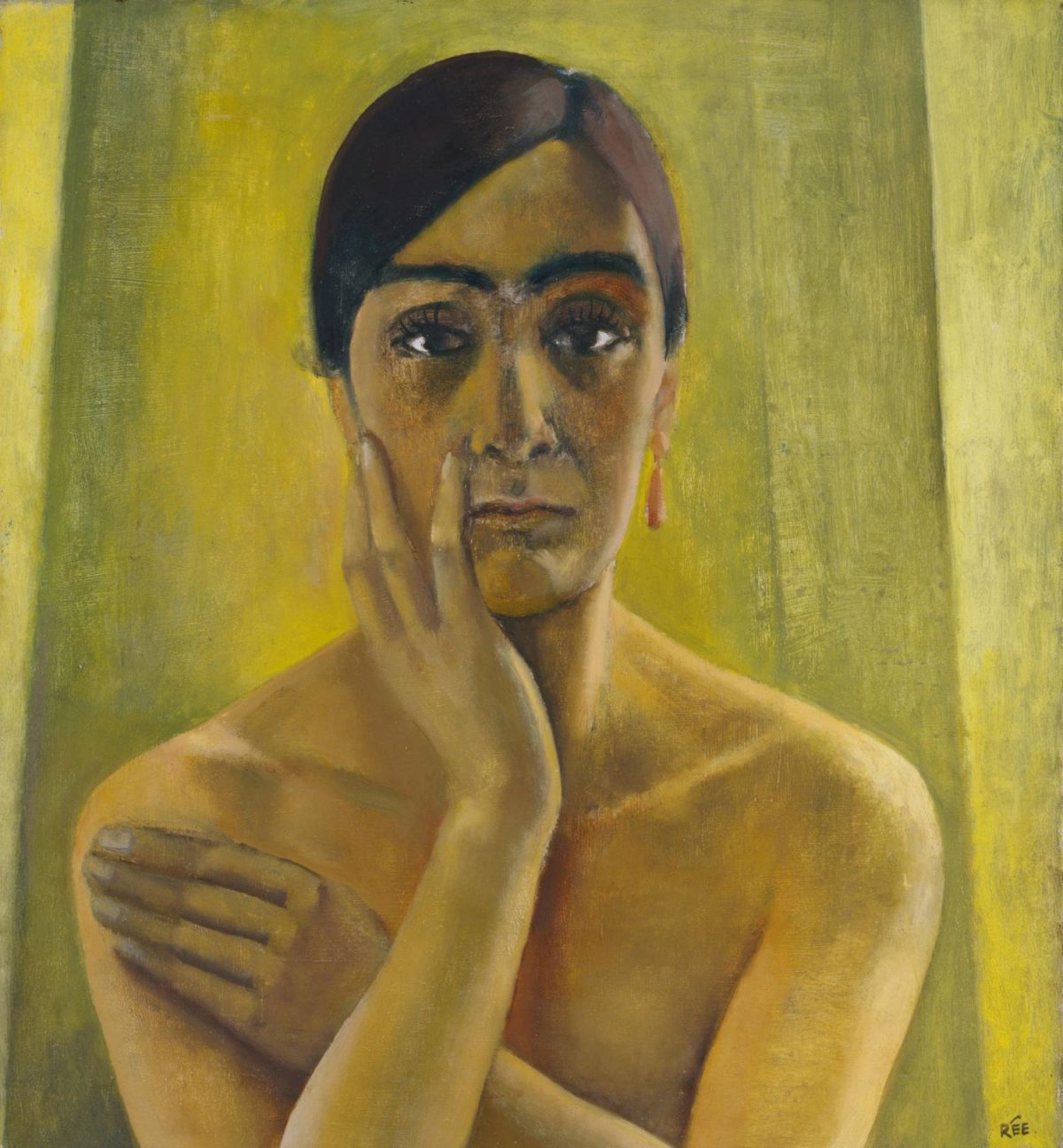

Teresina, 1922–1925.

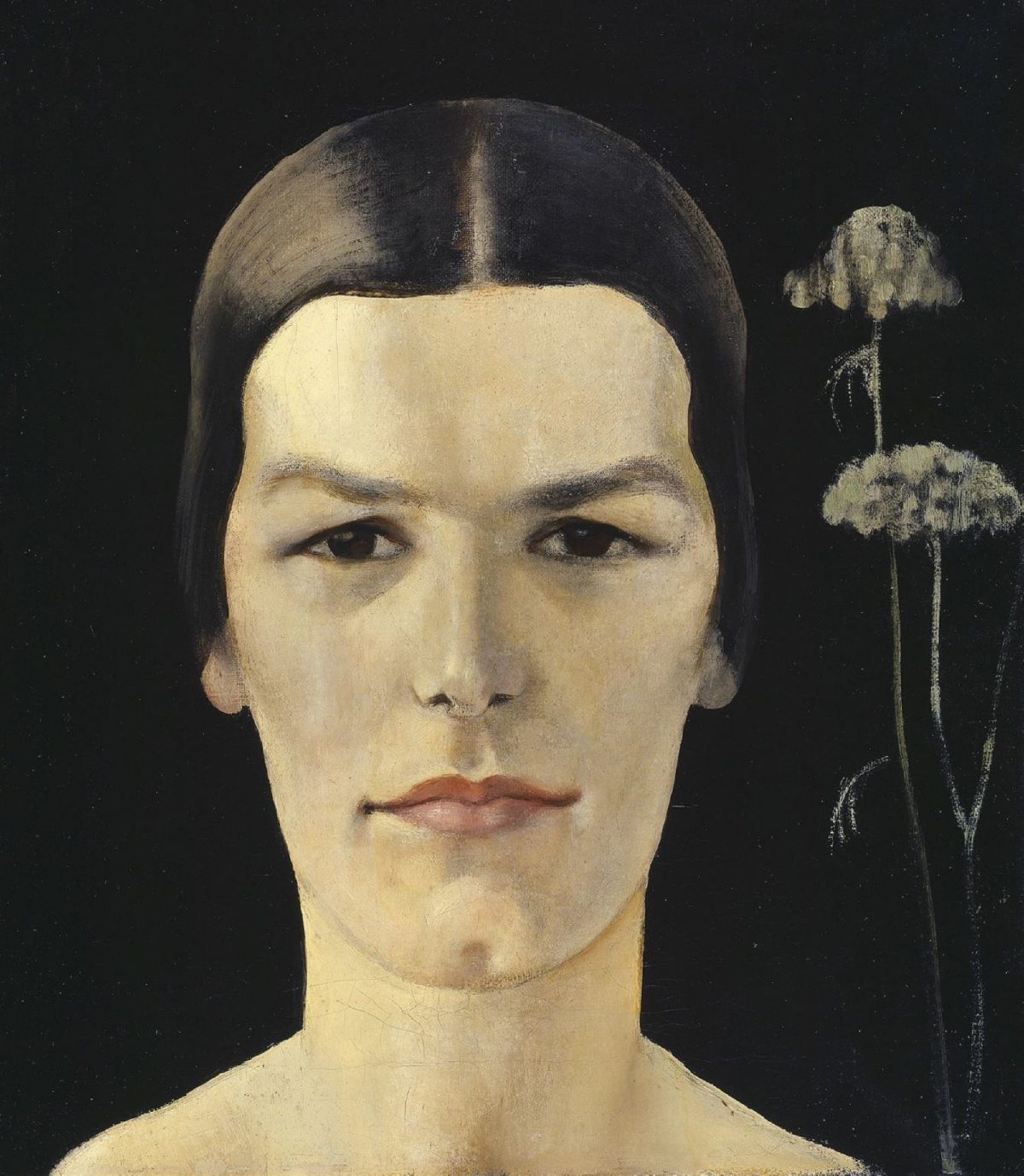

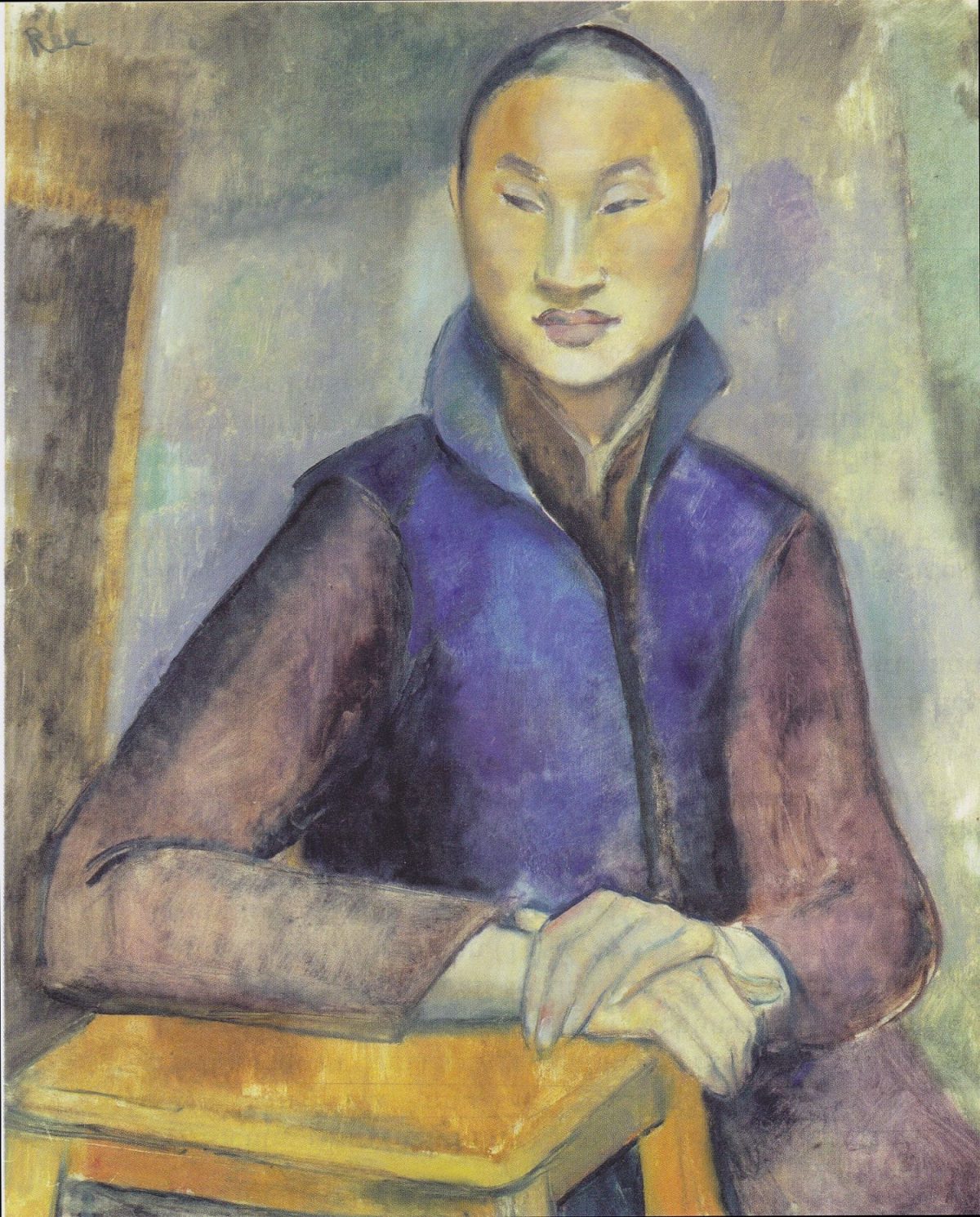

Young Chinese, 1919.

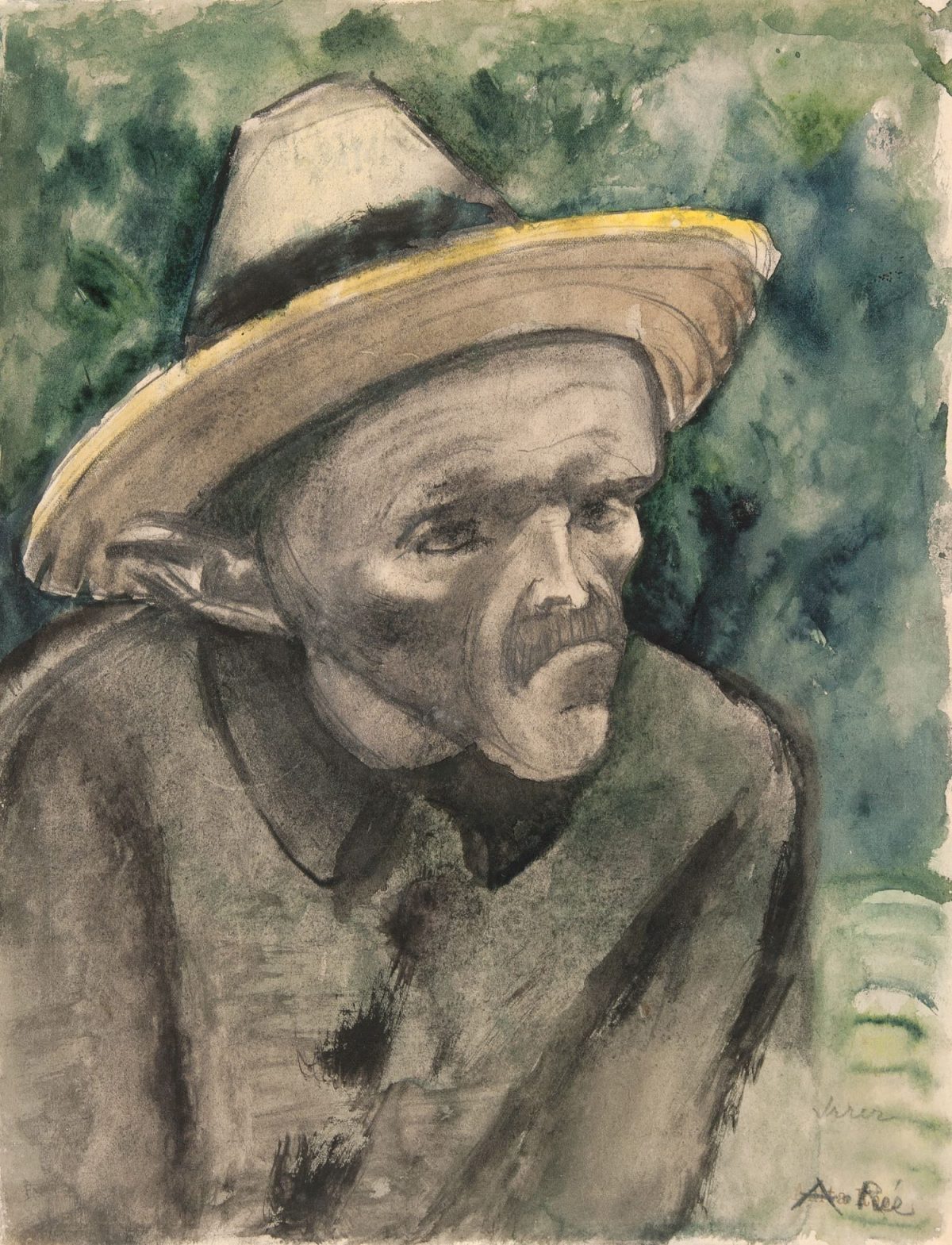

Portrait of Dr. Malte Wagner, 1920.

Still life with an orange tree, ca. 1920.

Semi-nude self-portrait in front of prickly pear cactus, circa 1922 and 1925.

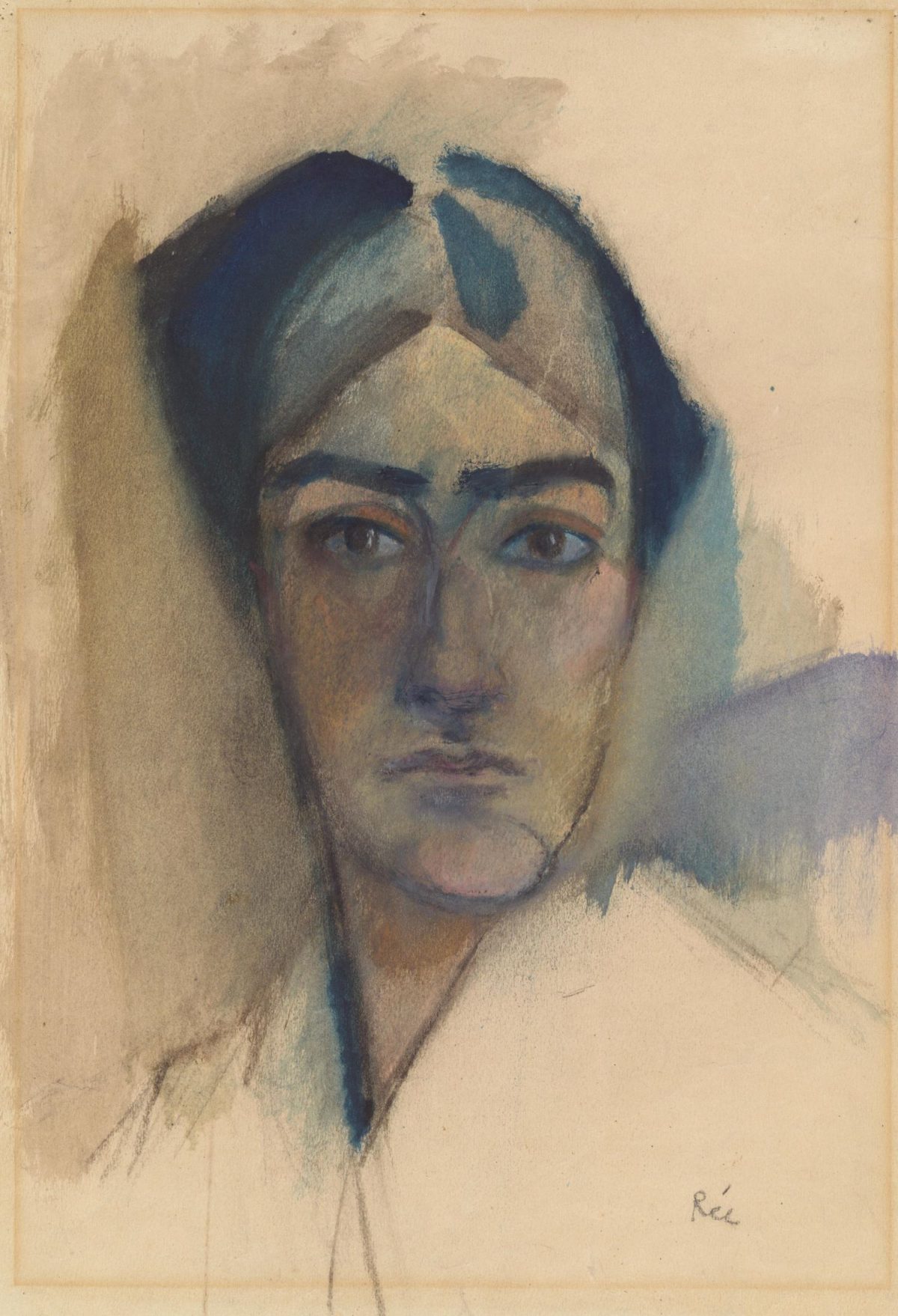

Self-portrait, ca. 1913.

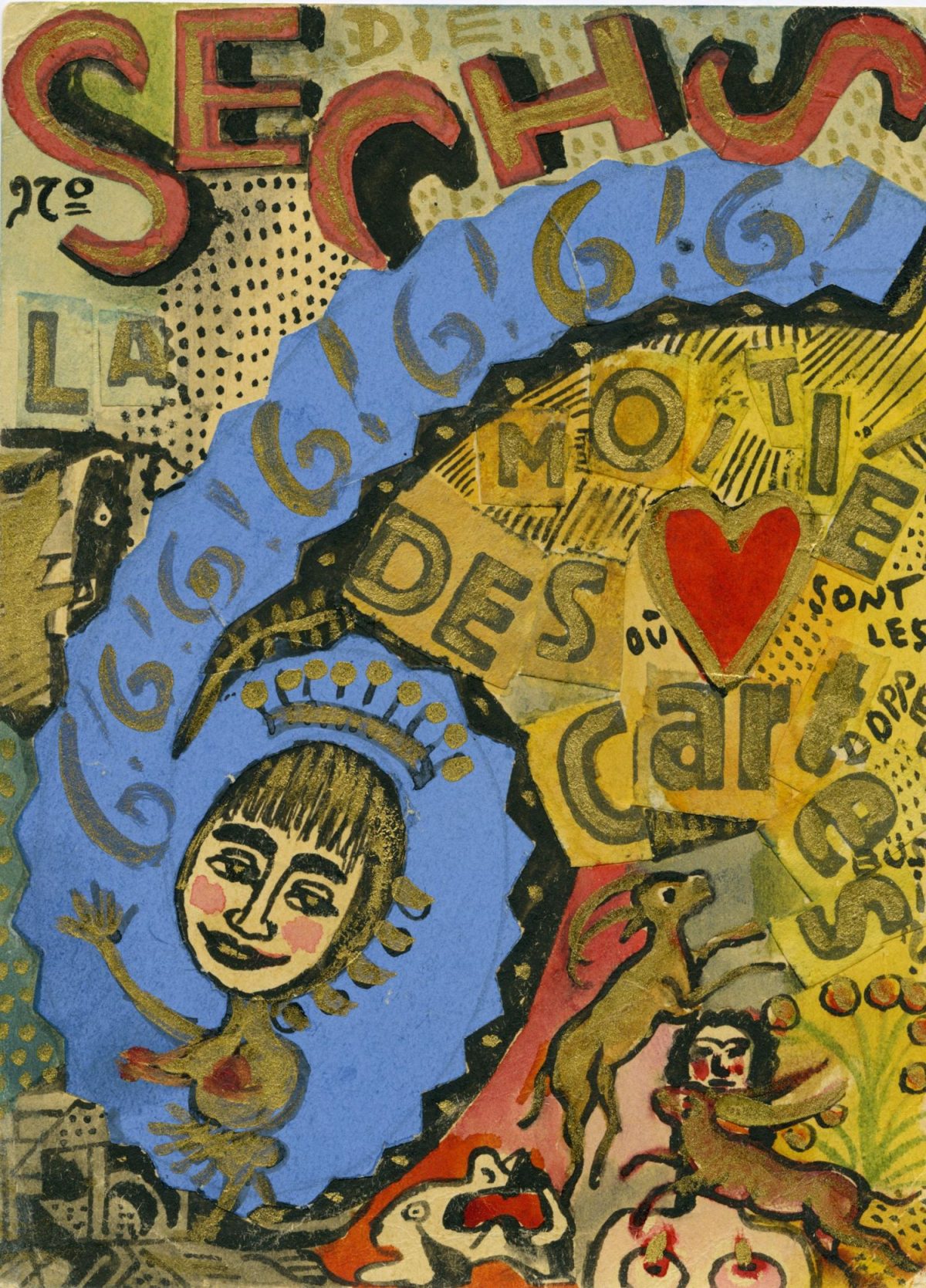

6. Doppelbüsi-Karte, 1929.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.