In 1979, Tom Wolfe published The Right Stuff, a thrilling and personal account of the Mercury Seven – the Project Mercury Astronauts; the first seven Americans chosen to go into space. There are libraries of more detailed books on the subject, but none capture the spirit of the program and the times better than Wolfe’s masterpiece.

In his work, Wolfe looks at each of the Mercury Seven, and so we’ll do the same. But before we launch, it’s important to mention the guy who paved the way – the man who each of the Mercury Seven revered (indeed, every pilot in the country idolized) – Chuck Yeager.

Captain Chuck Yeager with the X-1 supersonic research aircraft in 1947, shortly after breaking the sound barrier. (US Air Force)

Yeager was such a bad ass that before his historic flight breaking the sound barrier, he got drunk at a bar, got on a horse, and rode through a fence, breaking two ribs. He didn’t want the military doctors to know, or they’d cancel the mission; so, he went to a rural doctor far from Edwards Air Force Base and had his ribs taped. On the day of his mission, he was in such pain, he couldn’t close the cockpit, and had to use a broken broom handle to get it shut.

Chuck Yeager, his kids and wife Glennis (with Betty Paige hair style).

He was devoted father and husband, but at the same time a fearless pilot. During WWII, he was a highly decorated fighter pilot, once shooting down 5 enemy planes in a single day. When he was shot down over France, he escaped to Spain and helped them build bombs (!) – and on the escape route he helped his navigator who’d been shot in the knee… by cutting the tendon that held his leg hanging below the knee, then tied off the leg with a spare shirt made of parachute silk!

After the war, Yeager was a test pilot out in the barren California desert of Edwards AFB. And it was from this group, the military test pilot, that NASA chose its Mercury Seven.

From Top Left: Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, Gordon Cooper \ From Bottom Left: Wally Schirra, Deke Slayton, John Glenn Scott Carpenter. (Note that Slayton and Glenn are wearing spray painted work boots!)

The post-war test pilot in the 1950s had an incredibly high death rate. Literally a quarter of them died. Wolfe’s novel describes the grisly details of life as a test pilot, where it seemed there was a funeral to attend every week. Low wages, crummy military housing, and an ungodly mortality rate – why did these guys do it?

(L to R) Cooper, Schirra (partially obscured), Shepard, Grissom, Glenn, Slayton, and Carpenter

The reason they did it is the meaning behind Wolfe’s title: they felt they had the Right Stuff. It was an intangible, difficult to put into words state of mind. Knowing that you are doing something that is so elite, so demanding of courage and skill, that only a handful of people on the planet could do, imbued these guys with a swagger, Zen and feeling of purpose – the Right Stuff.

The recently selected seven are shown the “couches”, molded exactly to the contours of each astronaut’s body.

Initially, the space program was a bit “iffy”, and the seven were tempted to decline the offer. One reason was that they weren’t really piloting the craft – they would be more like passengers (a dirty word for these maverick test pilots). They’d heard their idol Yeager wasn’t impressed either – the test pilots at Edwards AFB were calling it “Spam in a Can” referring to the fact that they’d basically just be meat shot into space like a cannonball. A far cry from the in-control, highly skilled aeronautics they were used to.

Finally, to add a humiliating cherry on top – the first mission would be “piloted” by a chimpanzee. For decorated fighter pilots and daring and courageous test pilots endowed by their creator with The Right Stuff, the fact that a chimp could do it, was almost too much to endure.

But soon, that unease would lift once the entire nation embraced these seven as national heroes.

The Mercury Seven examine a model of their rocket. Take note of Gus Grissom, bottom left. He doesn’t seem too thrilled. He had a hard time dealing with the photographers and media. Indeed, each had their own approach to the mission, and their own persona. Let’s start with the first guy in space…

Alan B. Shepard Jr. right before the Mercury-Redstone 3 (MR-3) flight, the first American human spaceflight. April 20, 1961

Alan Shepard was selected to be the first of the seven – the first American in space. Wolfe recounts perfectly the hours of waiting Shepard endured before liftoff, sitting in his squashed capsule – having to go to the bathroom. They actually hadn’t accounted for a means for the astronaut to take a leak! After all, the mission would be under an hour (they didn’t plan on the four hour delay). Also, Shephard had to see Earth from space in black & white because the periscope filter couldn’t be adjusted. (For some reason, this fact frustrates me to no end.

Bathroom and B&W filter issues aside, the mission went flawlessly, and history was made. Alan Shepard, already a household name, was now Celeb Royale.

Second in line was Gus Grissom…

Grissom had a poor country background, and definitely lacked the polish of Alan Shepard. But he had an impeccable record and had been training as Shepard’s backup, so was the natural choice to go next. Upon landing in July 1961, Grissom didn’t receive near the adulation as Shepard had enjoyed, primarily due to the fact that he was basically just repeating the same mission – he wasn’t “the first”.

Grissom at home with his kids and wife Betty.

Grissom’s voyage was also a little tainted by a hiccup at the landing. He prematurely shot open the hatch, which allowed seawater to enter the capsule. The helicopter was unable to lift the heavy capsule and it sunk like a stone to the bottom of the ocean. Grissom said the hatch had ejected on its own, but it is likely he did it accidentally.

Third in line was John Glenn. Everyone expected him to go first – of the seven, he took the training and preparation the most seriously. Perhaps more importantly, he was super comfortable in front of the press, and cut the perfect image for the media: ultra-religious, family man, dedicated to his country.

It was fate that Glenn would go third, because this particular mission brought an unprecedented amount of fanfare. On February 20th, 1962 Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth. Upon touchdown, the entire country was cheering.

In a singularly fascinating scene in Wolfe’s book, we find Glenn’s wife at her home watching the mission on television. Her yard is crammed full of reporters – and then, the Vice President of The United States, Lyndon Johnson, makes a surprise visit to her doorstep! But poor Annie Glenn suffered from a stutter, and couldn’t bear to speak on camera, let alone to the VP in front of the press.

A few years later in 1965 – John Glenn, son John David, and Annie.

So, with his pressure suit still on, John Glenn tells a frantic Annie on the phone to not open the door. To literally tell the VP to f**k off. This moment will forever endear me to John Glenn. Fresh from touching down after orbiting the earth, still in his space-gear, his primary concern is his wife — and the cajones to tell LBJ to take a hike!

The wives of the Mercury Seven figure prominently in Wolfe’s story (and now captured in The Astronaut Wives Club). Annie Glenn is at top, second from left.

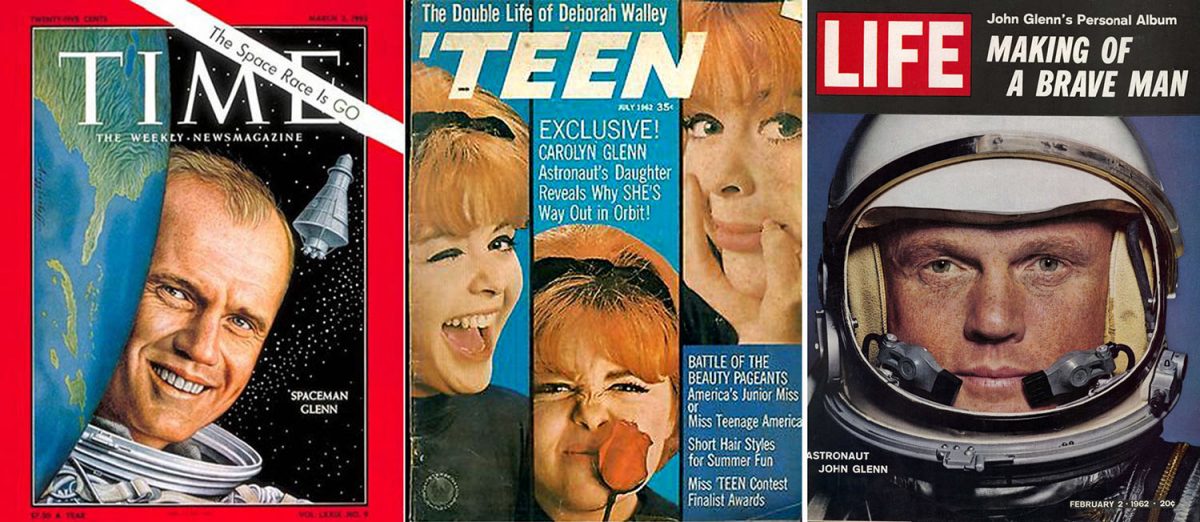

John Glenn covers flank daughter’s cover: “Carolyn Glenn Astronaut’s Daughter Reveals Why SHE’S Way Out in Orbit!”

These days, we don’t really have any national heroes – we’re all so divided, with patriotism often a dirty word. So, it’s hard for us to comprehend how honored Glenn was in 1962; it was like George Washington turned up to eleven. Subsequently, John F. Kennedy embraced the hero – and greatly benefited from the association. The space program had become a unifying, patriotic force, and JFK was able to easily fund a massive budget for NASA.

Meanwhile, Chuck Yeager continued test missions; he and his colleagues were going faster and faster, and higher and higher in spacecraft that they were actually piloting – not just “Spam in a Can”. But it that didn’t matter anymore – John Glenn had made astronauts into American heroes; celebrities of unimpeachable character, idols of a nation.

Next up was Scott Carpenter….

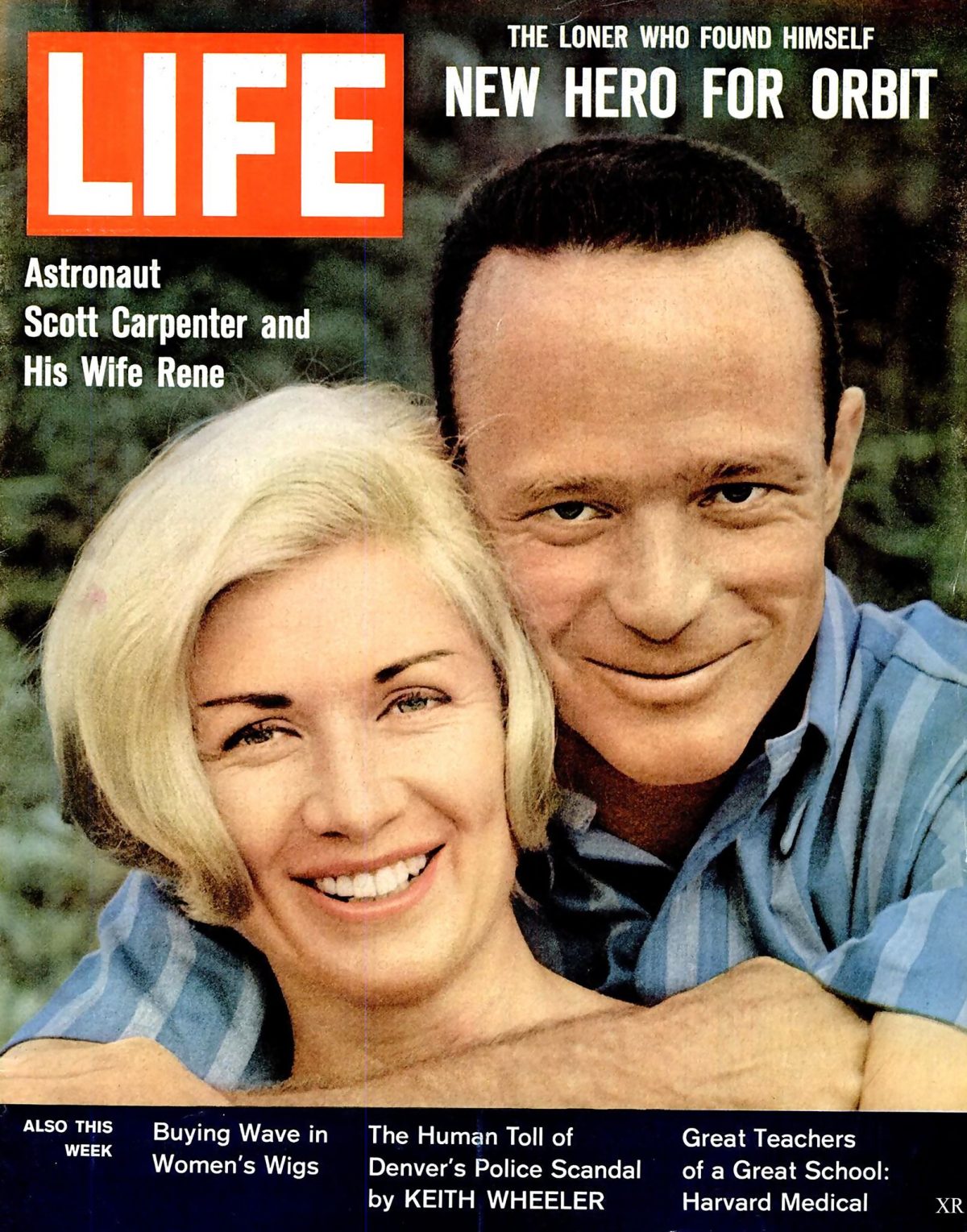

Carpenter didn’t have the war record or even the flight test experience to match up to most of the seven, but he did so well in the preliminary health and psychological exams, he went to the front of the line. He was Glenn’s backup, and more-or-less repeated Glenn’s mission, but with a battery of scientific tests added to the schedule.

Carpenter and family meet with JFK.

Carpenter and his photogenic wife, Rene, were also heralded as national idols, but it wasn’t quite the same as before. Firstly, his mission was, as stated, basically a repeat of Glenn’s. Second, the landing wasn’t without problems. Carpenter needlessly wasted fuel and misaligned his landing spot, putting him miles off course. After a brief period of frantically searching for him, with the nation wondering if he was alive, Carpenter was found… but he was sidelined for future missions. He left the space program a couple years later.

Next up, Wally Schirra…

While Americans were congratulating themselves for their mastery of space, the Soviets were launching manned spacecraft going around the planet up to 64 orbits; far outpacing the US. Kennedy knew they had to up their game try for additional orbits.

Shirra’s mission was to orbit six times – a mission he performed flawlessly. In stark contrast to Carpenter’s which was riddled with mistakes, his execution was perfect – Chuck Yeager would be proud.

Wally, daughter and wife, Jo.

Of all of the seven, Shirra’s mission got the least attention. Sure, he didn’t do it for the glory – but watching the ticker tape parades for the other astronauts, then to receive barely any recognition, was a bit disheartening. Shirra would soon find out why this was – Kennedy was a bit preoccupied by something called The Cuban Missile Crisis.

The last solo American mission to space was manned by “Gordo” Cooper.

Deke Slayton was the most experienced, and thereby deserving of the slot for the next trip. However, he failed a physical and the honor went to the seventh of the seven: Gordon “Gordo” Cooper. He’d always been the most quiet, and the last to step into the limelight. But he was about to go for an unprecedented 22 orbits on May 15, 1963.

What was truly exceptional about this trip was the way Cooper handled a barrage of problems. Over and over again, Cooper had to manually redirect. In the end, Cooper landed safe, but it was after overcoming numerous malfunctions that could have easily ended in disaster. Again, Chuck Yeager would have been proud.

And so ends the story of the Mercury program, and also Tom Wolfe’s novel. Of course, the stories of these men didn’t end there. Glenn would become senator, Grissom would die in the Apollo I fire, and Alan Shepard would be the fifth man to walk on the moon.

Six months after Cooper’s mission, Kennedy would be shot. The space program would go on, but something intangible was lost. Americans would land on the moon in July 1969, but nothing could recreate those glorious days of the Mercury Seven.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.