At half-past ten on St Valentine’s Day, 1929 in a cold, unheated brick garage at 2122 North Clark Street, Chicago, six members of the Bugs Moran gang were sitting around waiting for a consignment of illegal whisky due to be delivered that morning. Moran himself was meant to be there too but had slept in and was late.

A Cadillac screeched to a halt outside and three men dressed as policemen accompanied by two men in civilian clothes entered the premises. They told the six gangsters and John May, a mechanic working in the garage, to stand in a row with their hands up against the wall. A few seconds and ninety bullets later the men were left slumped dead and dying on the floor.

Not long after the killings, John Miller, a reporter on the newspaper Chicago American arrived on the scene and wrote:

Sprawled grotesquely at the base of the bullet-riddled stone wall were six distorted bodies; a seventh lay slumped over a wooden chair. One of the officers called out, ‘This one’s Pete Gusenberg, an ex-con and the chief gunner for the Drucci-Moran gang. Here’s Al Weinshank, the North Side booze runner, and Artie Davis from the West Side mob. And this was James Clark, Bugs Moran’s brother-in-law. Here what’s left of Doc Schwimmer.’

The other member of Moran’s gang, not mentioned by the reporter, was Frank Gusenberg, miraculously still alive and had been taken away to hospital. He died three hours later but only after saying to the police he would tell them nothing.

Another reporter at the scene, called O’Rourke and also from the Chicago American, memorably remarked after looking down at his shoes:

I’ve got more brains on my feet than I have in my head.

Although everybody in Chicago knew it was an organised killing by Al Capone, who was conveniently wintering in Miami at the time of the murders, not one single person ever went to jail for pulling a trigger that morning.

“These murders went out of the comprehension of a civilized city,” the Chicago Tribune wrote a few days later. “The butchering of seven men by open daylight raises this question for Chicago: Is it helpless?”

A crowd outside the Clark Street garage, owned by George “Bugs” Moran, where the St. Valentine’s Day massacre took place on Feb. 14, 1929.

The funeral for brothers Frank and Peter Gusenberg was held on Feb. 18, 1929, and was packed with floral arrangments, including one heart believed to be sent from gang leader George “Bugs” Moran. The brothers were leaders in the Bugs Moran gang.

Capt. William ‘Shoes’ Schoemaker shows four machine guns at the inquest for the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre on April 19, 1929.

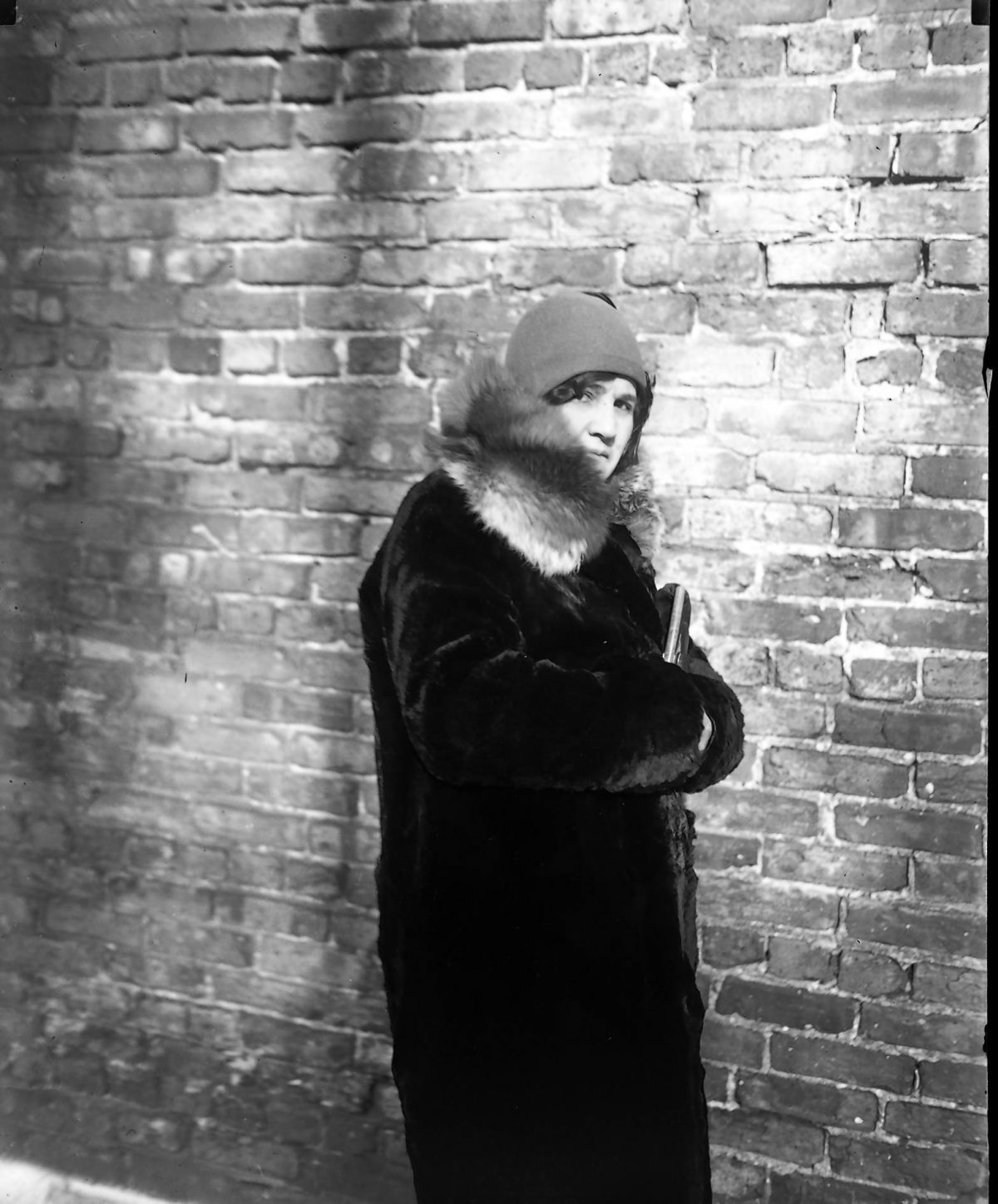

Mrs. Alphonsine Morin, who lived across the street from the garage saw a couple of ‘policemen’ coming out of the garage after hearing the gunshots. She received a letter a few days later telling her to “keep your mouth shut.” Morin, seen here around February 1929, left Chicago the minute she received the letter.

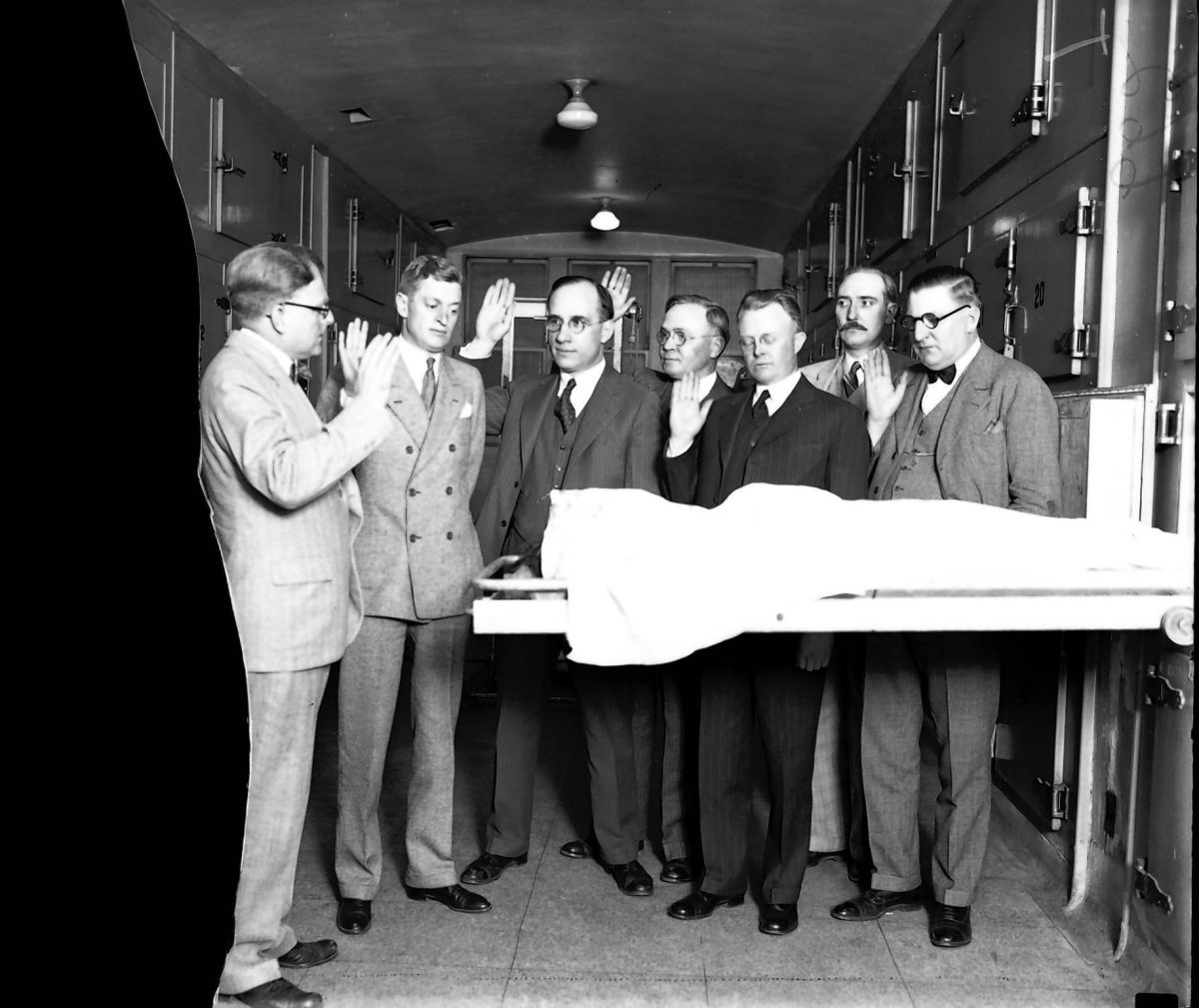

, led by Coroner Herman N. Bundesen, left, at the inquest for the Clark Street St. Valentine’s Day Massacre on Feb. 15, 1929. The coroner said 20 to 25 bullets were found in each of the seven bodies.

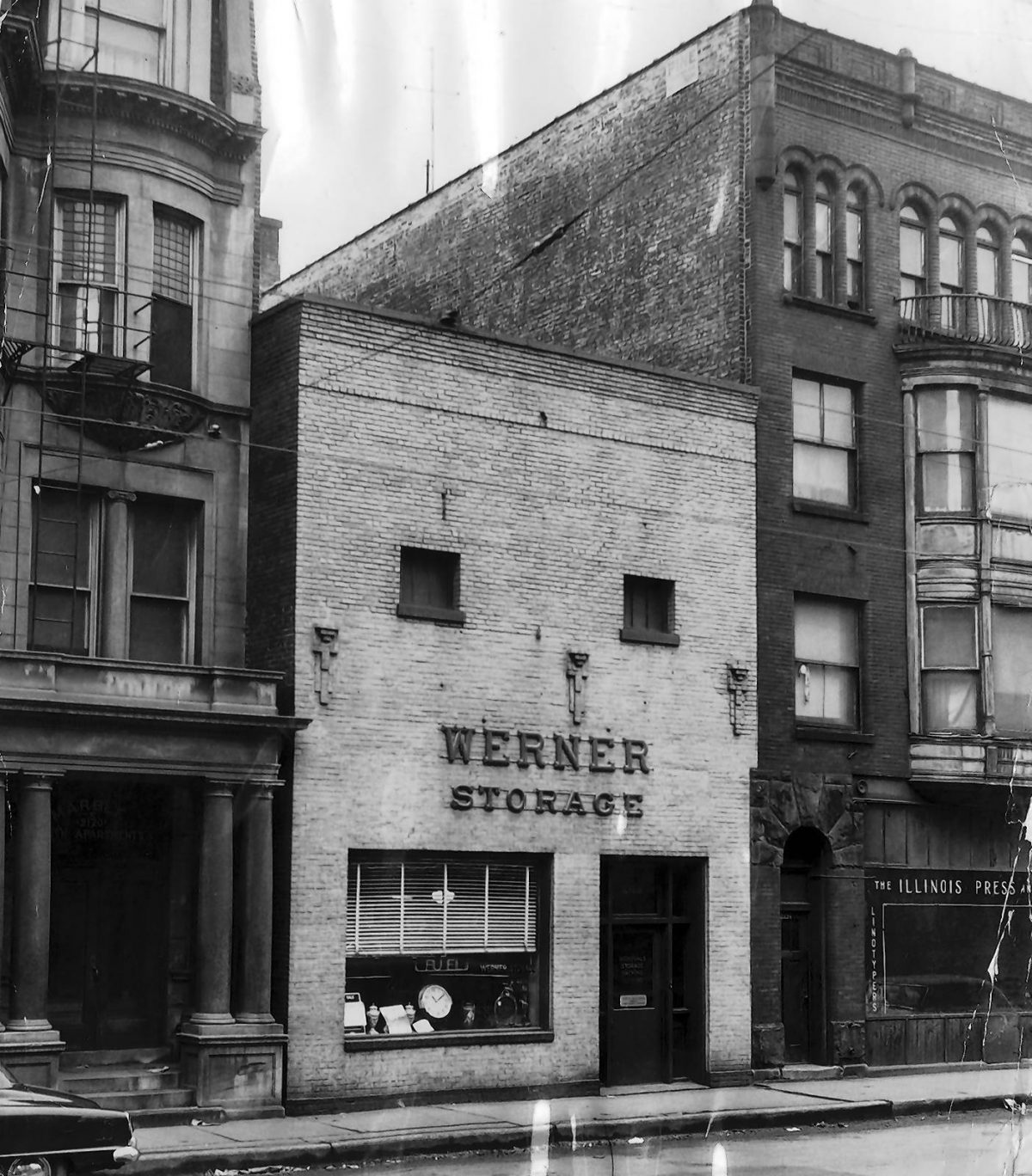

The Werner Storage Company building located at 2122 N. Clark St., shown here in 1953 is the scene of the St. Valentine’s Day massacre on Feb. 14, 1929. The building was torn down December 1967.

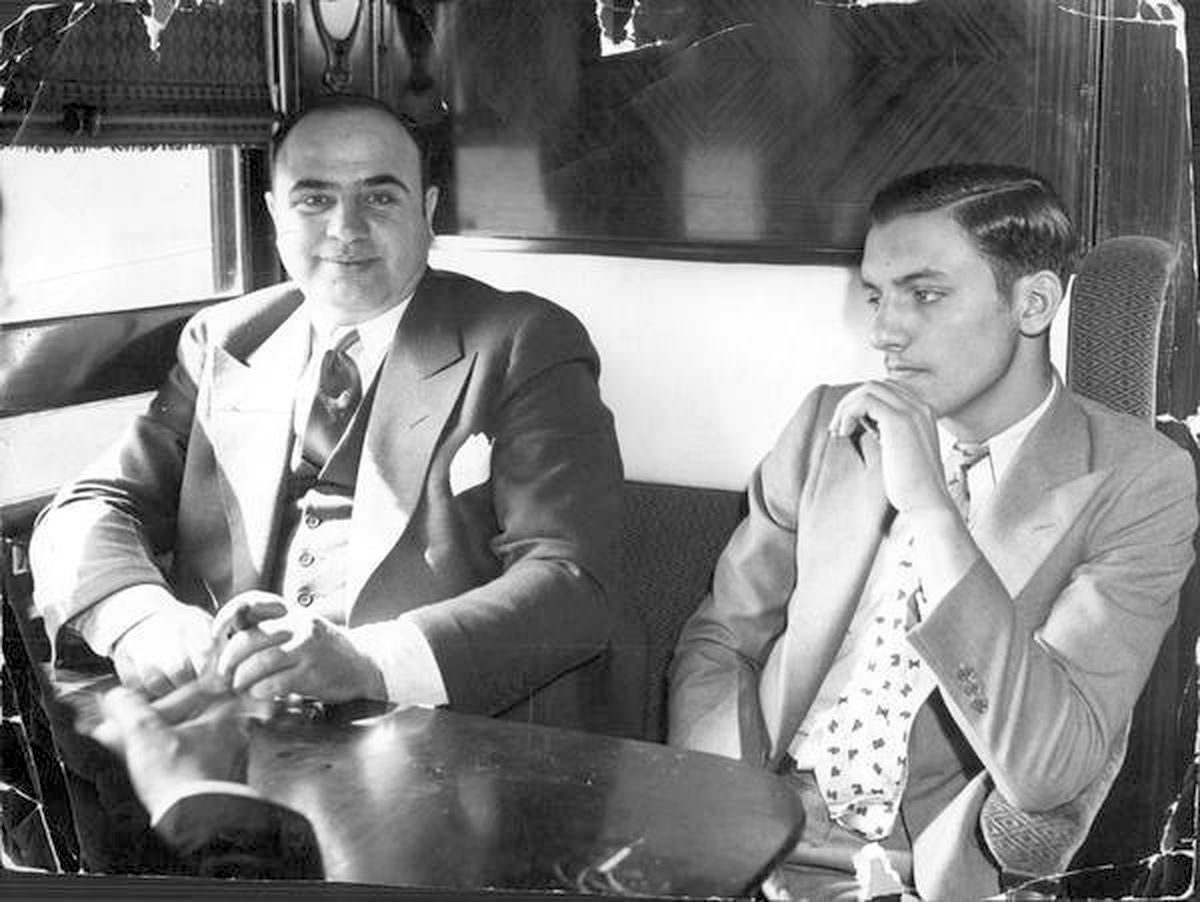

Al Capone and a fellow prisoner, who was not connected to Capone’s case, ride a train in May 1932 en route to Atlanta from Chicago. Both were on their way to serve their prison sentences, Capone for tax evasion and his berth mate for auto theft.

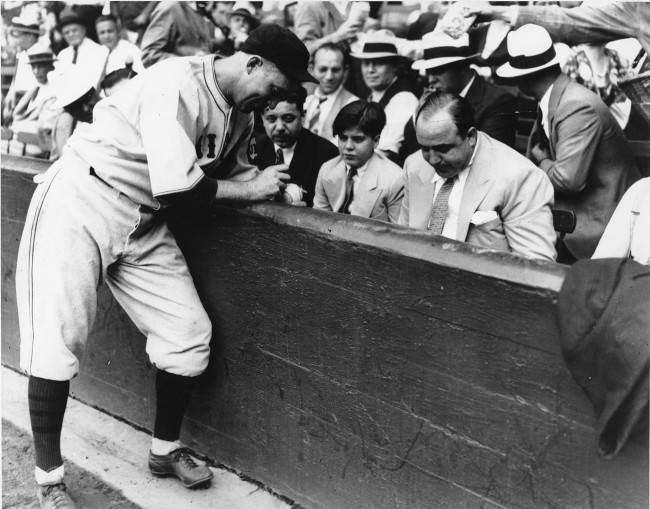

Surrounded by his watchful lieutenants, Chicago’s crime boss Al Capone, right, and his 12-year-old son, Al Jr., gets Chicago Cubs’ Gabby Hartnett to autograph a baseball just before the Cubs defeated the White Sox, 3-0 on Sept. 9, 1931, in Chicago. Seventy years after Capone’s death, the world’s most famous gangster still draws a crowd in Chicago and visitors from all over the world come to search for anything Capone. (AP Photo/file)

The Werner Storage Company building, shown Feb. 4, 1959, eight years before it was demolished. (AP Photo/Harry L. Hall)

The garage in Clark Street was demolished in 1967 but the bricks from the North wall were bought by a Canadian businessman. His name was George Patey and he opened a Roaring Twenties themed nightclub called the Banjo Palace in 1971. He painstakingly rebuilt the St Valentine Massacre wall inside the men’s toilets and patrons were invited to try and hit targets by urinating on the plexiglass covered bricks. Three times a week Patey would generously allow his female customers into the the men’s toilets to look at the bullet-pocked wall.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.