“I put my negatives in a banker’s box, where they stayed for twenty years, following me from apartment to apartment to house and garage, until now… The pictures I made of my family had an immediate frisson for me, a wallop way beyond the surprise success of their exposure or the virtues of their composition.”

– Thomas Alleman

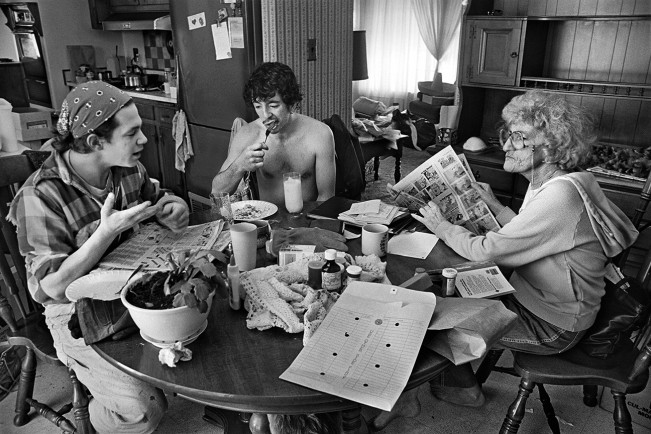

Between the ages of 24 and 32, Thomas Alleman took pictures of his family. “In the years after an indifferent college career, I waited tables and taught myself photography by practicing on my friends and family,” he says. “I carried my Minolta and a 28mm lens back home to Detroit for holidays and occasional weekends.

“The pictures I made of my family had an immediate frisson for me, a wallop way beyond the surprise success of their exposure or the virtues of their composition. After years away from the house on Newport Street, I returned with a heightened awareness of the layers of subtext in every situation, and I snapped away at it from every angle, and some of my images hinted at the ghosts and passions running beneath the everyday household dramas I beheld.”

The Unwinding

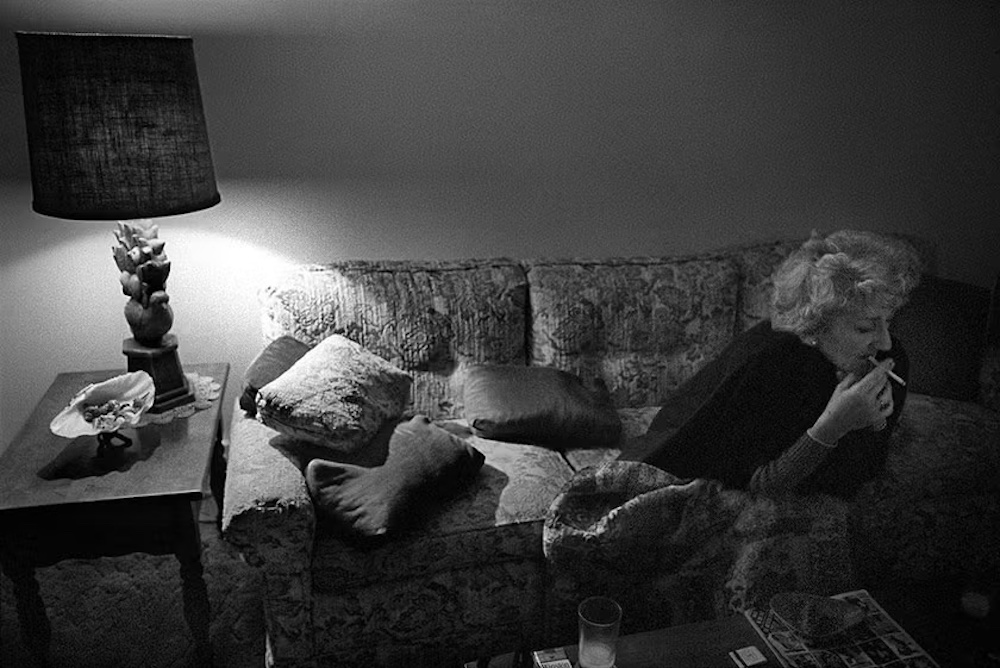

Not long after his parents married in 1957, they realised that they weren’t in love but decided “to stay the course and just slog through whatever life seemed available to folks like them in times like those”. Thomas, the oldest of the couple’s three sons, watched his mother’s health deteriorate. A chain smoker since 14, she “checked out of her marriage as her health deteriorated”, turning the family couch into her bedroom.

When his father lost his job, she returned to work in a ball-bearing factory. One of Alleman’s brothers became an alcoholic in high school. Another was “restless and angry”. Thomas left home for college.

“I began practicing my pictures of my mother and the family in 1982, just as their downward trajectory began slowly but certainly spiraling. In a few short years in the mid-70s, my father’s career had fizzled out, and he’d developed diabetes and had bypass surgery; he spent the 80’s pacing the house each day, waiting for his heart to explode. My youngest brother, still in high school, was already an alcoholic; our middle brother was restless and angry, and inclined to operatic denunciations of us all, apropos of nothing…

“I stood before them while they writhed and withered, shouting at each other, limping through worn-out rooms, and I made photographs for my own edification, and they let me.”

– Thomas Alleman

“…there was certainly a layer of weird theater playing out, in any case: if another wide-angle camera were somehow affixed to a high corner of the kitchen, or hidden behind a bookcase in the living room, it would have shown me there, too, part of the scene, the one studying and sketching those hapless players: arrogant, omniscient, blessed by luck. That’s the scene at it’s most fucked-up, and it hovers beyond the edges of these pictures. But they allowed all that without a word, and I carried on for eight years.”

– Thomas Alleman

“Of course, it separated me from them, and I knew that after a while. But I couldn’t think of a better way to survive those dreary years, to be with them but not of them. Over time, both my confidence and my ambivalence grew, each fed by my ‘mastery’ of that ‘material’. I felt a wobbly kind of shame, and wondered it I’d betrayed them all.”

“As it became clearer that my mother’s final months were near – she spent half of her final year in emergency rooms and ICUs, breathless, frail and afraid – I was forced to confront two obvious futures: I could stay the course and ‘finish my work’ as she died, and I’d have a complicated and intimate book to show for my long ‘travail’. Or, I could cease and desist my grim project, forget the whole damned thing, and join her in her final season as a son and companion, and experience her death as nakedly as possible, and send her off with a kind of dignity. I’m sorry to admit, the decision wasn’t easy, or quickly made. But I decided, after all, to stop making pictures of her on New Year’s Eve, 1990, while she rested uneasily in a room in the Pulmonary Ward at Mission Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina.”

After Dad’s Funeral, 1985.

“She lived her most vulnerable hours out in the open, where we children could watch her struggle for breath while we played quietly around her in the dawn. And that theme became dominant in all the years to come: we were intimate witnesses of her decline.”

– Thomas Alleman

Outside Asheville, North Carolina, August 1990, with Bob.

“I saw with a certain clarity the currents of anger and despair that roiled the surface of my family’s daily affairs and recognized for the first time the subtext that burbled below all that: the ghosts and passions and long-simmering resentment that were unacknowledged but powerful, driving forces in that household drama.”

– Thomas Alleman

Hospital Room, Asheville, North Carolina, New Year’s Eve 1990, with Andy.

Hospital, Asheville, North Carolina, New Year’s Eve 1990. The last frame

“She was brave and smart and forward-thinking. I believe that if she’d had a chance to use her ravaged body to demonstrate the ruination that culture wreaks upon one and all, she would happily have done so.”

Via: Slate, Lens Scratch, Analog Forever, Catalyst

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.