“I have no trouble with the idea of my art serving a purpose. I want to have an impact at a time when people are so baffled, so in need of help.”

– Käthe Kollwitz diary entry, December 1922

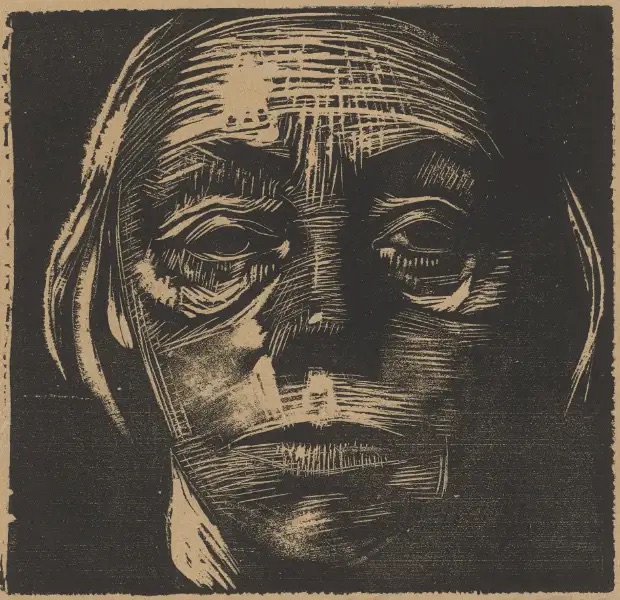

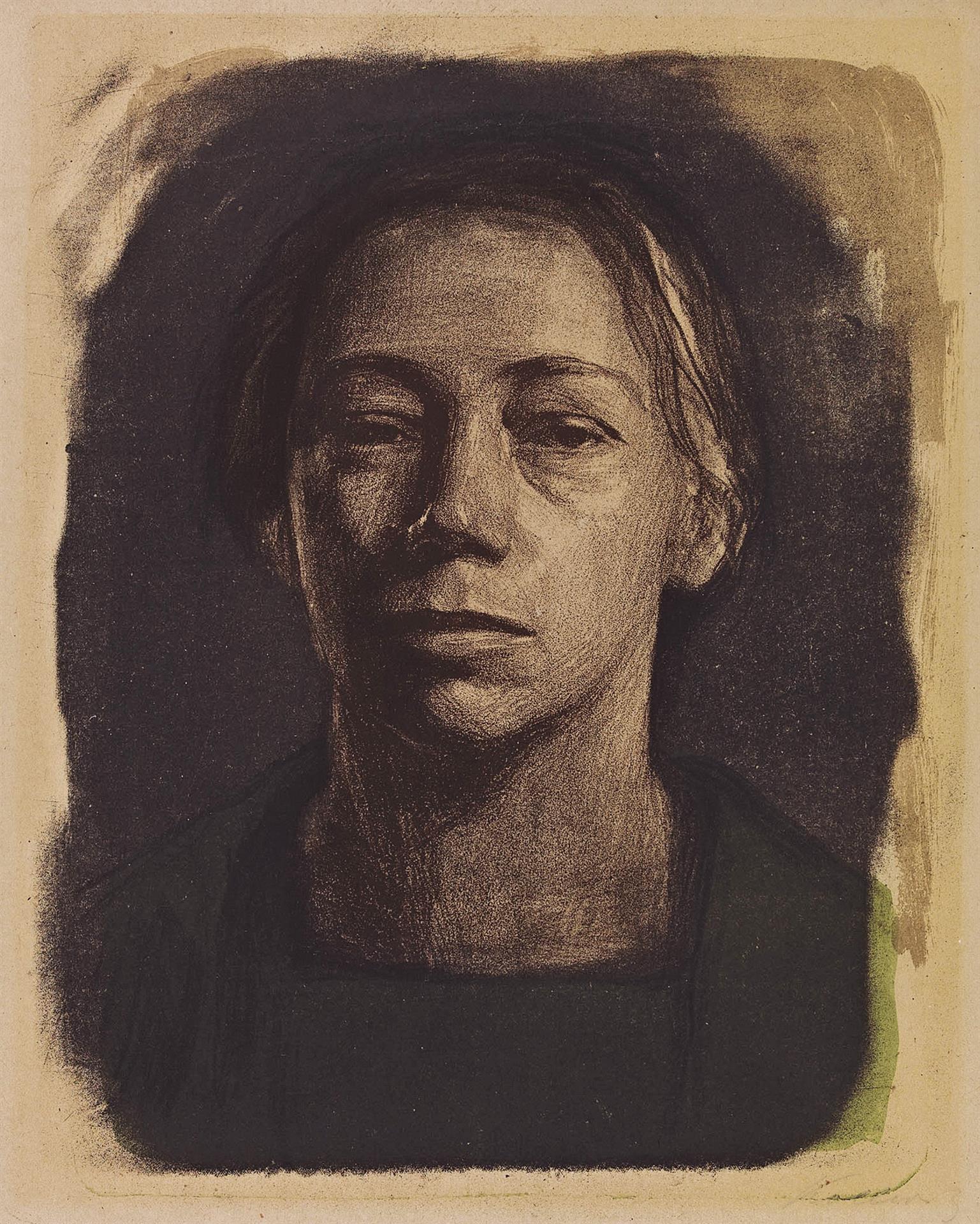

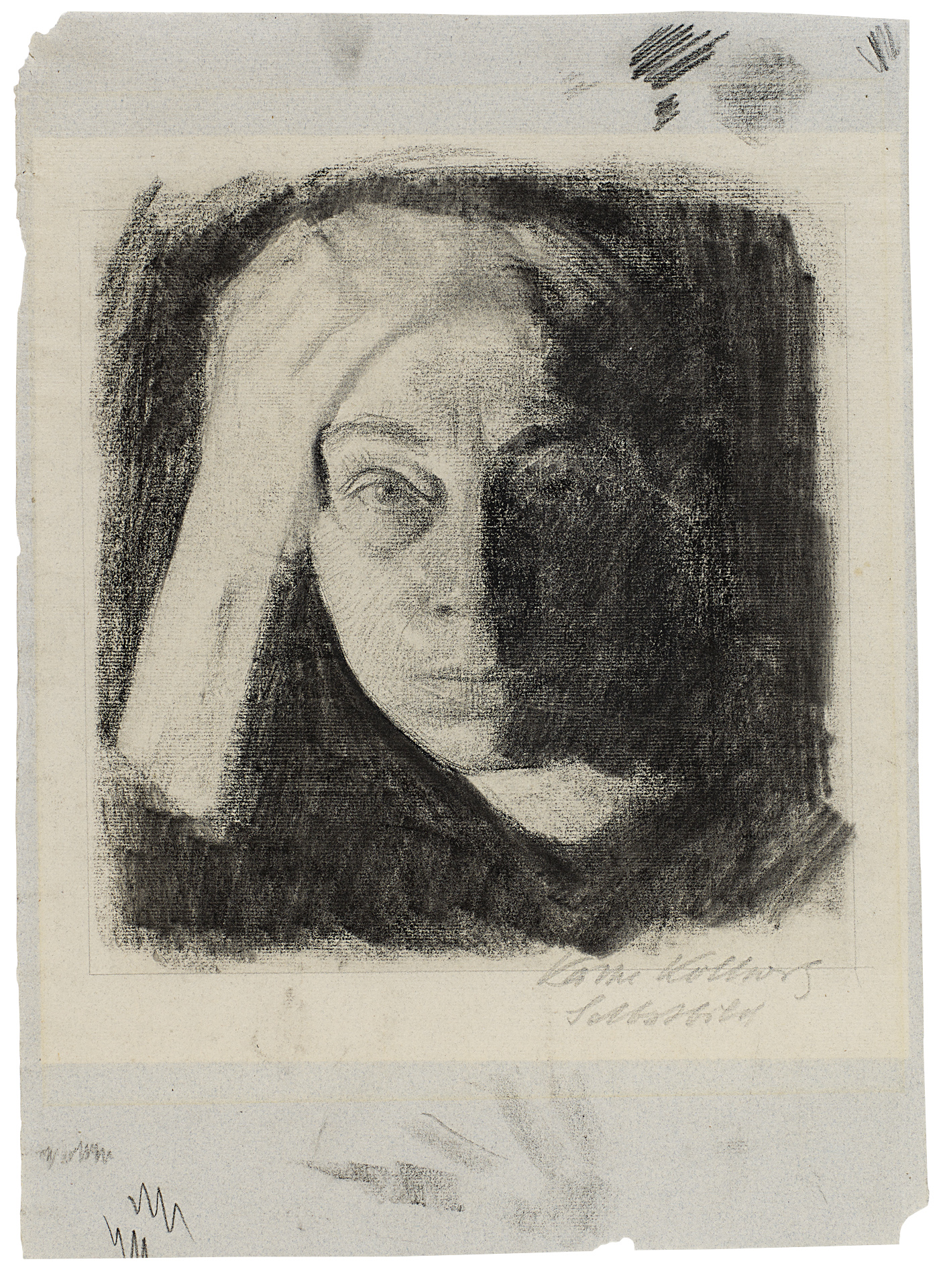

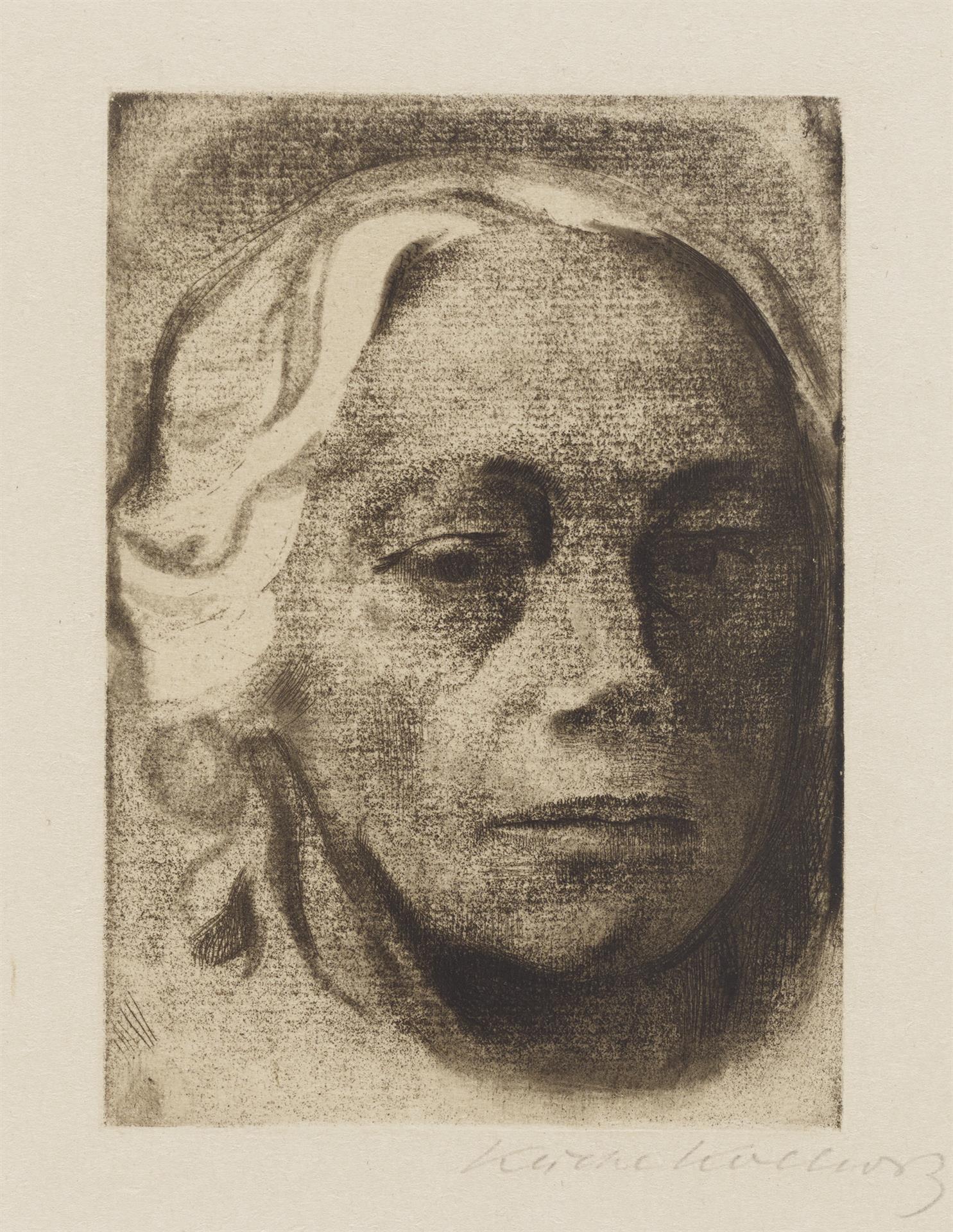

Käthe Kollwitz (8 July 1867 – 22 April 1945) made over 100 self-portraits of her expressive face. She called these intense self-interrogations a “visual form of a soliloquy”. We’re posting some of them here.

Having started out as a painter, German artist Käthe Kollwitz focused on printmaking and drawing, seeing both visual artforms as more capable of reaching the intense truth of things. “I happened to read Max Klinger’s book ‘Painting and Drawing’. That’s when I realised: I’m not a painter at all!” she wrote in her memoir Rückblicke auf frühere Zeit, 1941.

In this work, Klinger presents drawing and printmaking as more truthful than other media, and well able to express the artist’s experience and deliver greater emotional impact. While painting strives for harmony and beauty, graphic art can convey powerful, immediate truths and show things many do not want to see.

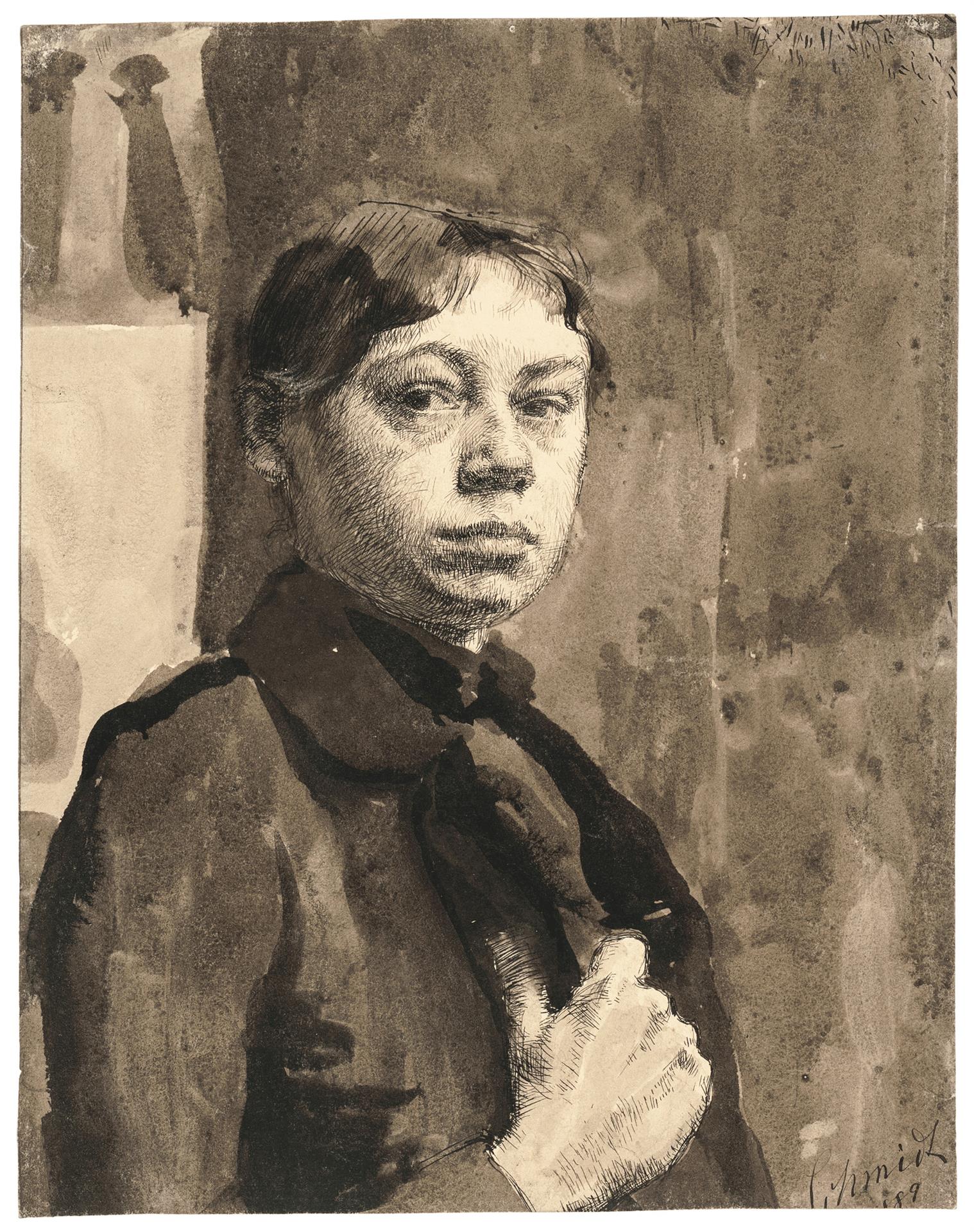

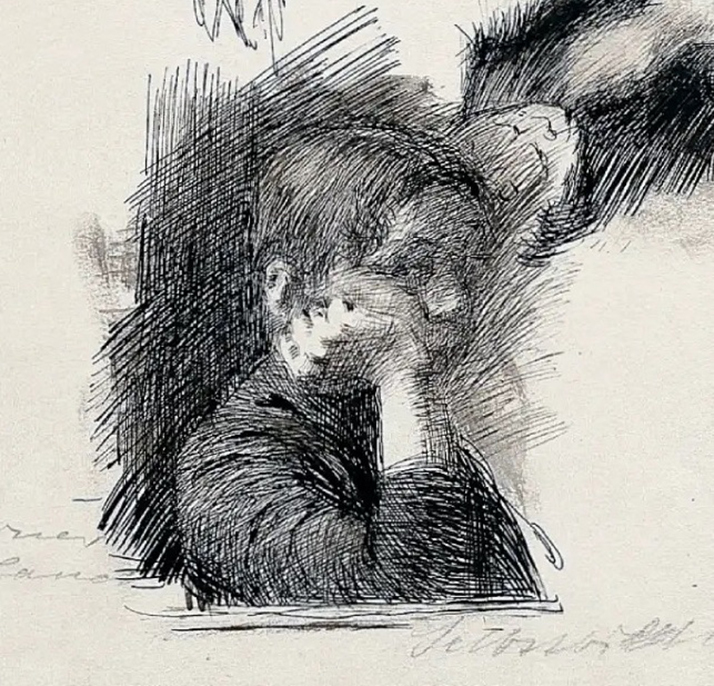

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-Portrait, 1888 – Pen and brush in sepia on drawing paper, 260 x 248 mm, on permanent loan from the estate of Marianne Fiedler at the Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

Through her pictures, Kollwitz was able to address existential human questions. She focuses on the individual, showing us the effects of living in a troubled society infected by poor social conditions and grief, fear, anxiety and loss.

And she saw much, living through the founding of the German Empire, Kaiser Wilhelm II’s long reign – during which he critiqued her representation of the human experience as “gutter art” for violating established beauty standards – the First and Second World Wars, the end of the German monarchy, the Weimar Republic and Nazi rule.

Käthe Kollwitz: Malweiber

Until 1919, women were banned from German art academies and colleges. Women were only allowed to engage in artistic activities for domestic use, such as embroidering cushions or drawing flowers. Young female artists were trained in professional organisations established by women that operated in the shadow of the academies. At 19, Kollwitz took lessons at the all-female painting and drawing school of the Verein der Künstlerinnen und Kunstfreundinnen zu Berlin.

She became one of the so-called Malweiber (painting maids) who lampooned the absurdity of their sex being deemed incapable of artistic expression by wearing painters’ coats out in public and adopting the very foreign Impressionist style of painting.

The name Malweiber was born in the title of a caricature by Bruno Paul (19 January 1874 – 17 August 1968) in the satirical weekly magazine Simplicissimus. In the illustration, we see a painter at his easel with a woman looking over his shoulder. The text under the caricature reads: “You see, Miss, there are two types of female painters: some want to get married and others have no talent either.”

“If, as is often the case now, art does nothing more than make misery even more hideous than it already is, then it sins against the German people”

– Kaiser Wilhelm II in the speech Die wahre Kunst, 1901

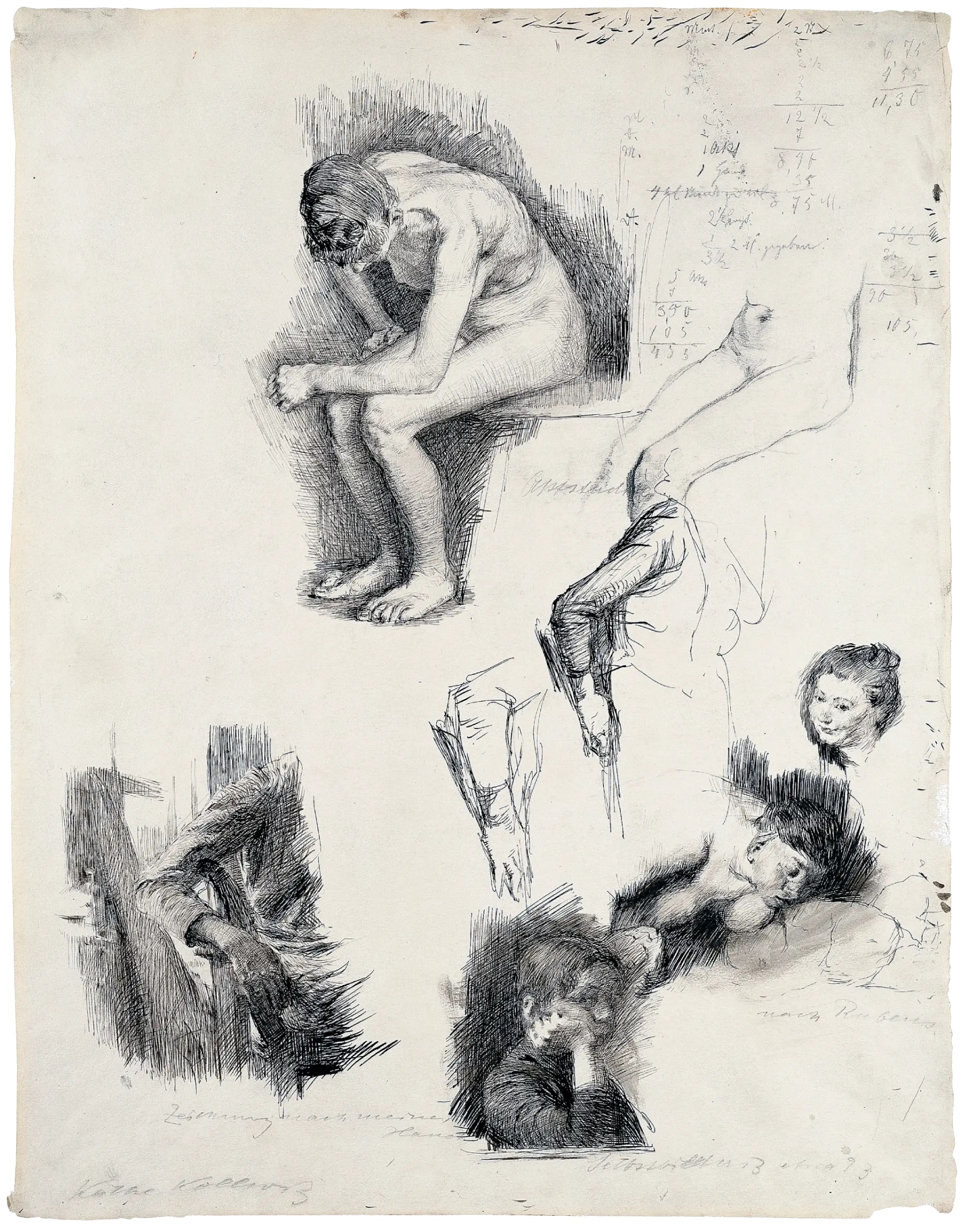

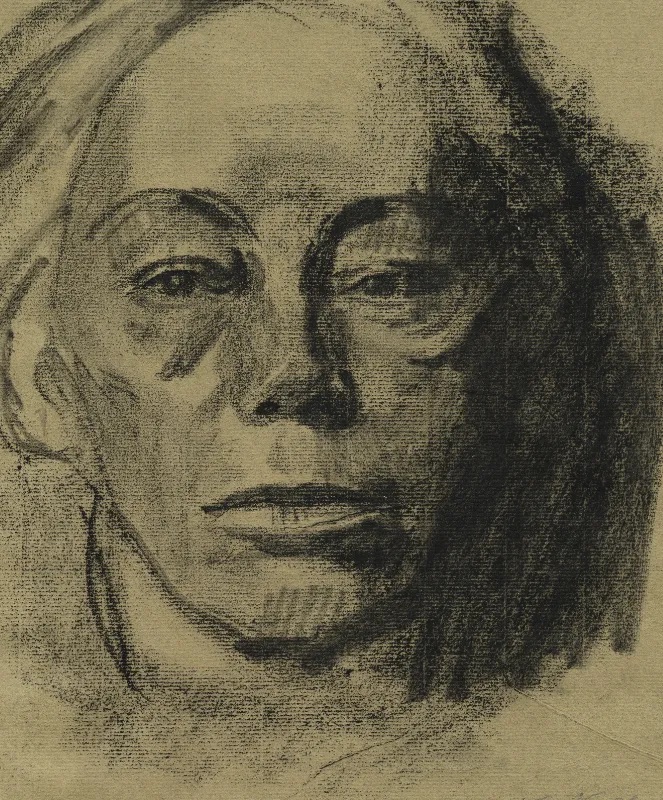

Above and in detail:

This page from her sketchbook held great significance for Kollwitz until the end of her life. It was a reminder of her training and a testament to her talent. It shows studies after Peter Paul Rubens and, at the bottom centre, a moody self-portrait. In 1888, after a year in Berlin, her father sent the young artist to Munich, where a lively art scene beckoned.

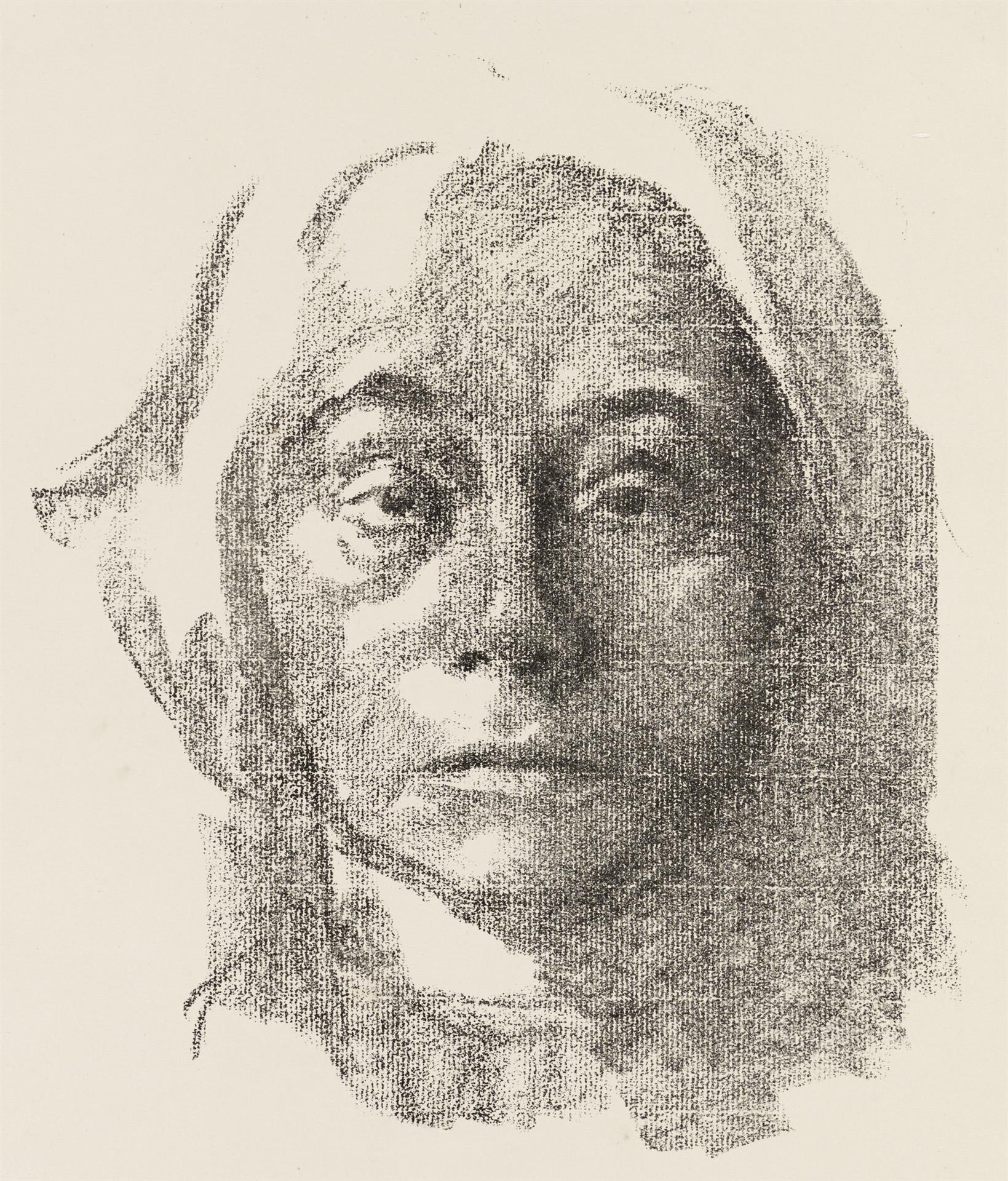

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-portrait en face, 1904

Self-portrait en face, c 1910

Kollwitz and War

Kollwitz was a pacifist who created a series of antiwar posters. As The Kollwitz museum in Cologne werites:

But it wasn’t until the painful experiences of World War I that she became an ardent opponent of militarism and war. Before then, like many modernists of her time – not just in Germany – she had shared a faith in the putative ‘cleansing’ power of war to do away with the old. Kollwitz once believed that the individual had to make sacrifices, initially agreeing with the war as “just”.

A woman frozen stiff with anxiety: Fear is Kollwitz’s contribution to the magazine Kriegszeit, edited and designed by artists associated with the Berlin Secession. The image betrays the artist’s incipient doubts about the war that had started to form in her mind by October of 1914 – just months after the outbreak of hostilities. Two days after this image appeared, Kollwitz learned that her younger son Peter had fallen – during the march of the German army through Belgium, an act of lawless aggression.

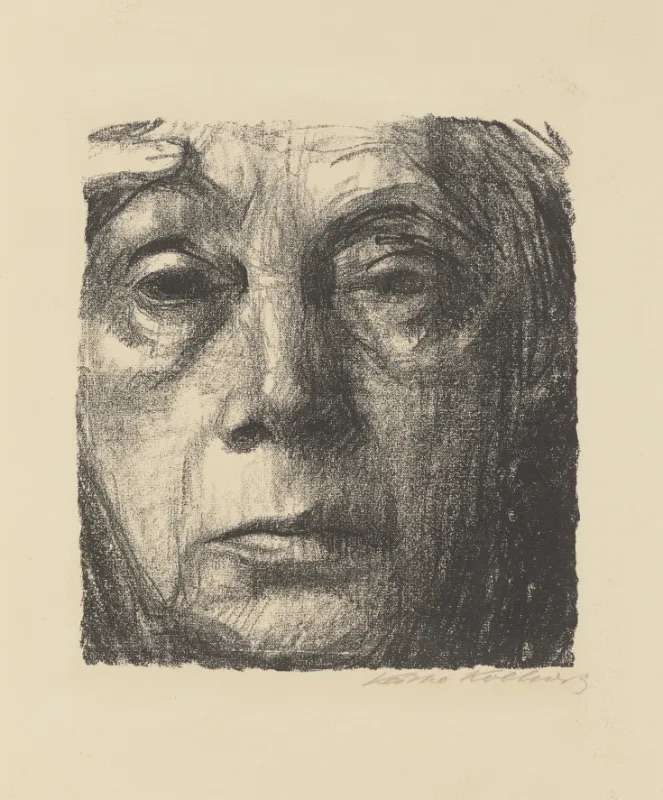

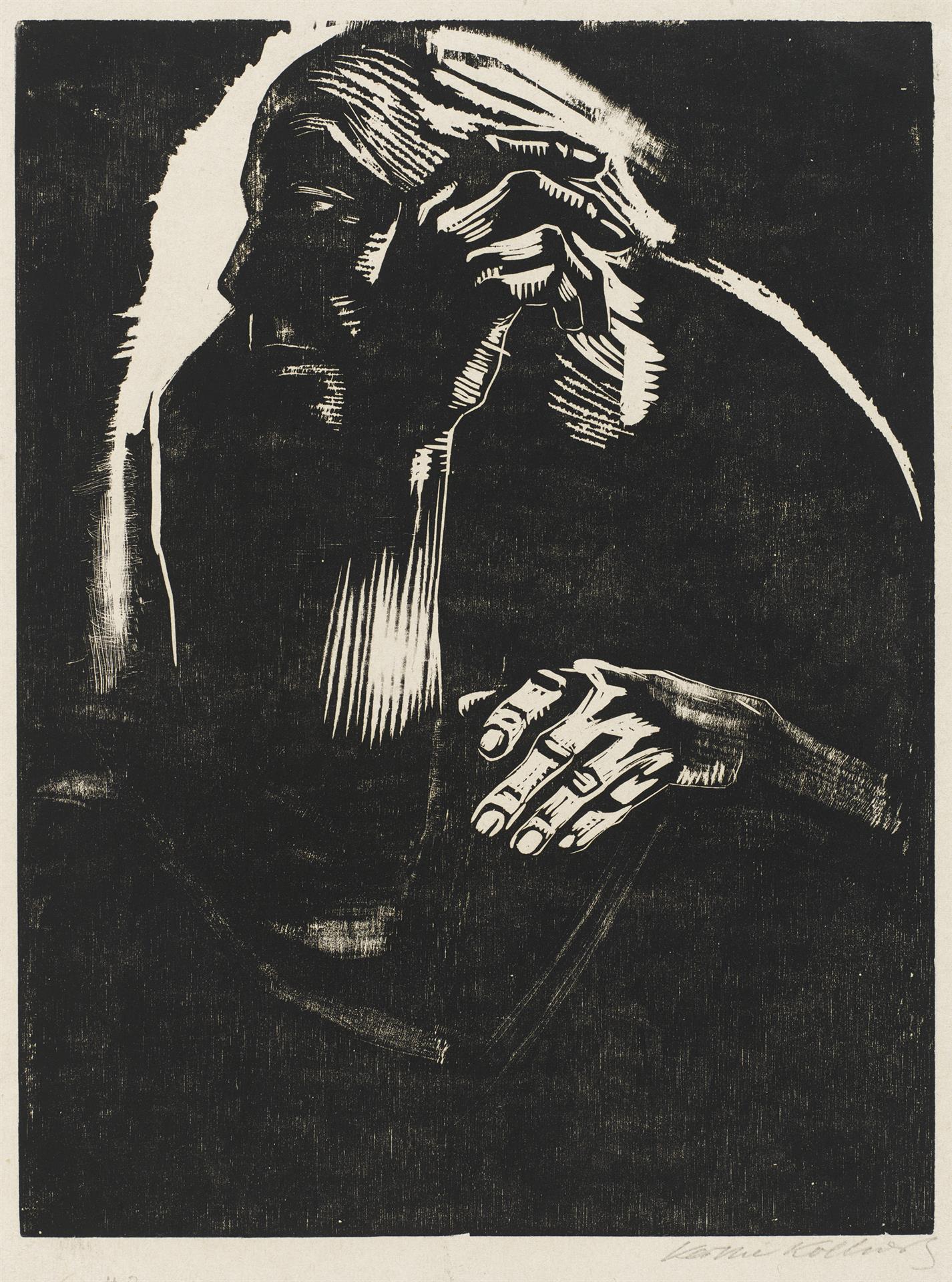

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-portrait, 1912

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-Portrait en Face, c. 1912-1915

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-portrait, 1924, woodcut

“When someone dies because he has been sick – even if he is still young—the event is so utterly beyond one’s powers that one must gradually become resigned to it. He is dead because it was not in his nature to live. But it is different in war. There was only one possibility, one point of view from which it could be justified: the free willing of it. And that in turn was possible only because there was the conviction that Germany was in the right and had the duty to defend herself. At the beginning it would have been wholly impossible for me to conceive of letting the boys go as parents must let their boys go now, without inwardly affirming it—letting them go simply to the slaughterhouse. There is what changes everything. The feeling that we were betrayed then, at the beginning. And perhaps Peter would still be living had it not been for this terrible betrayal. Peter and millions, many millions of other boys. All betrayed.”

– Käthe Kollwitz, 19 March 1918.

Images via: Städel Museum

Discover Käthe Kollwitz art in the shop.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.