Destined to be a leading light to the world, James Hodges Ellis (born James Hughes Bell, February 26, 1945 – December 12, 1998) was known to his fans as Orion. To others he was Elvis Presley. Ellis appeared with many artists, including Loretta Lynn, Jerry Lee Lewis, Tammy Wynette, Ricky Skaggs, Lee Greenwood, Gary Morris and the Oak Ridge Boys, but when Elvis died the two men’s similar singling styles made some think that the King’s death was a ruse. Elvis never did die, Elvis lives – and he does so as Orion.

Like the myriad Elvis impersonators, Orion was on the act, of course. As Mitch O’Connell writes: “Only in these great United States would the marketing concept of ‘Elvis didn’t die, but to escape the constant limelight and pressure, he fakes his death and remerges as Orion. So, to make it impossible for anyone to know who he is, he continues in the same profession, puts out albums, sounds just like himself, looks just like himself (his face filling up all 12″ of most of the covers), yet cleverly wears a domino mask to completely throw everyone off.”

‘Elvis’

The story of the singer Orion began as fiction and grew into a fanciful real-life tale that wound up trapping a desperate performer behind a mask he never wanted to put on, says Mitch. Unavoidably, the story was also about Elvis Presley — about the uncanny resemblance between an unknown singer’s voice and the voice of an American legend.

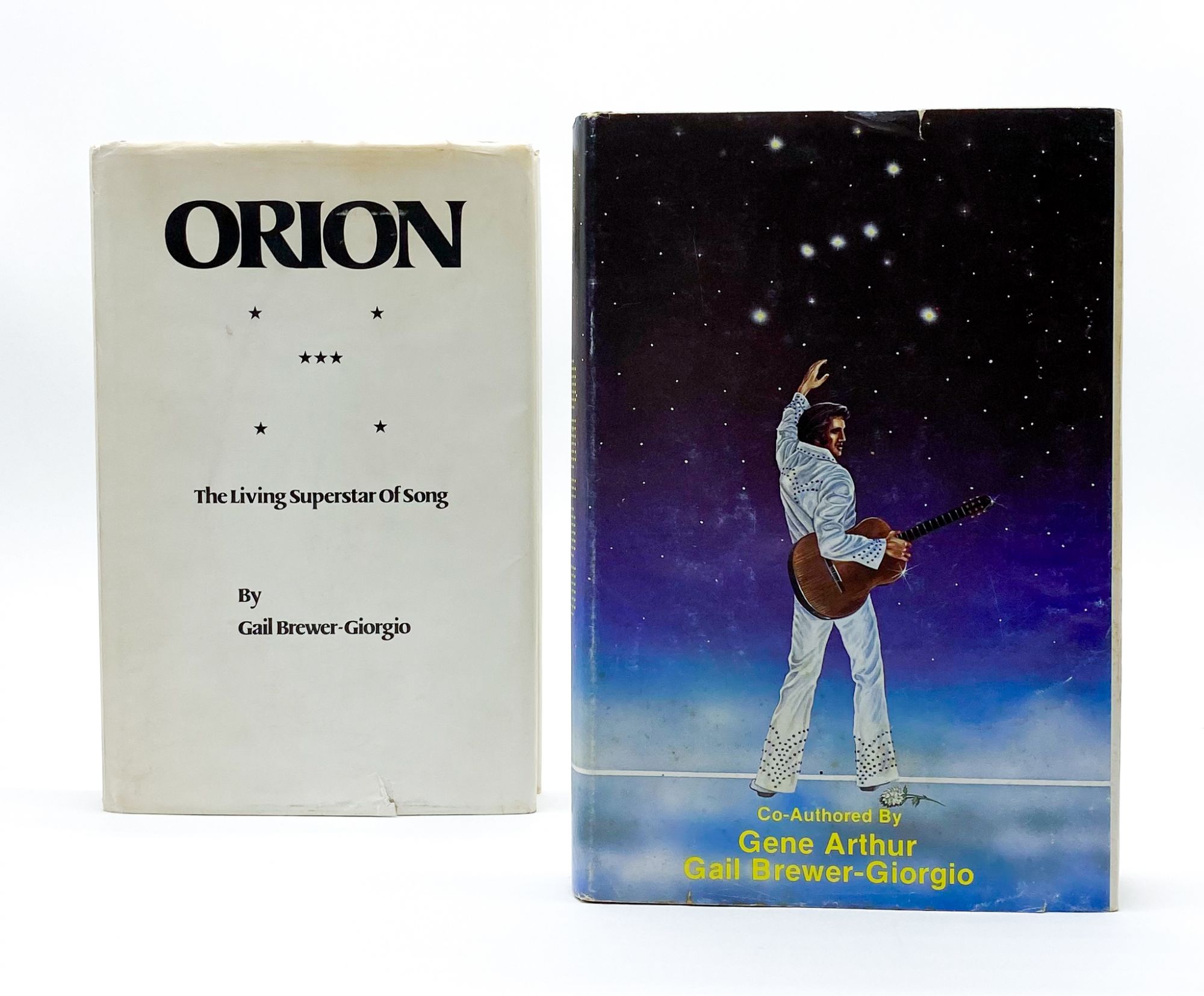

Orion and his producer, Shelby Singleton, fooled more than a few people but Orion was not their creation. He was the creation of Georgia-based writer Gail Brewer-Giorgio, who in the early 1970s wrote a novel about a charismatic rock ‘n’ roll singer, Orion Eckley Darnell. Desperately poor as he was good looking, Orion’s talent and charm shone and he was soon nicknamed – yep, you got it – ‘The King’.

But life has a habit of getting away from you. And Orion’s fame became a straightjacket to his living. Mobbed wherever he went, not knowing who to trust, he becomes a recluse. Alone, damaged and existing on diet of fast food and drugs. his famed lithe frame and snake-hips yield to bloating. He falls ever lower, growing ever more depressed.

But then.. (This is America folks! – and not the UK where he’d be eaten by his pet cats), hope shines. His father creates a wax figure of Orion’s own overweight image. The hero grows a beard, loses weight and fakes his own death in the mansion that has become his prison. After attending his own funeral, Orion drives into the sunset in a beat-up station wagon with luggage strapped to the roof. As he motors down the road, the first tribute song to the life and death of Orion blasts from his radio.

Brewer-Giorgio wrote Orion: The Living Superstar of Song before Elvis Presley’s death on Aug. 16, 1977. But she didn’t get it published until afterward. By then, she’d already gained a fan in Nashville-based record producer and music mogul Shelby Singleton, who had purchased the rights to the Sun Records catalog from famed record producer Sam Phillips in 1969 and relocated the company from Memphis to Nashville. Since Elvis had first come to fame on Sun, Singleton had a heightened interest in anything to do with Presley’s legacy.”

The Encounter

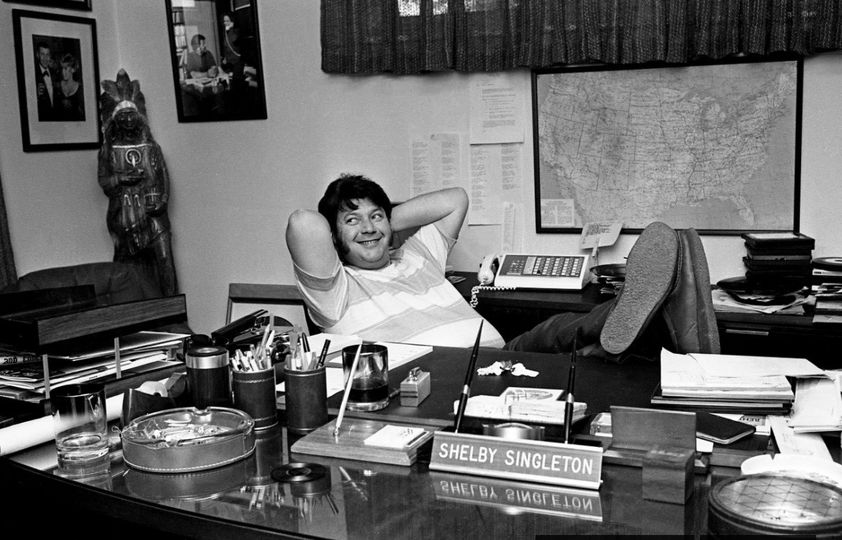

Producer Shelby Singleton (Jeannie C. Riley, Brook Benton, Ray Stevens) in his office on Belmont Blvd, June 1969. (Photo from The Tennessean)

Singleton and Jimmy Ellis met in the early 1970s. Ellis had been recording songs and yearning for a big break since 1964, when he first began issuing dramatic ballads and traditional rockabilly songs on the Dradco label. By the time he encountered Singleton, he’d spent nearly a decade pursuing a career as a romantic Southern crooner and hip-shaking rocker. But he’d found little success, partly because deejays and record executives said he sounded too much like a second-rate Elvis.”

Then, in 1972, a Florida record producer named Finlay Duncan sent Singleton a two-song single that Ellis had recorded in Fort Walton, Fla. When Singleton heard the song, he thought, “Man, either that is Elvis Presley singing, or it’s someone who sounds just like him.”

Once Duncan convinced Singleton that the singer indeed was Ellis rather than Elvis, the Nashville owner of Sun requested that the producer cut a couple more songs on the performer. Singleton made specific requests: “That’s Alright Mama” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” the two songs that launched Presley’s career on Sun Records in 1954. “I told them to try to duplicate the Elvis records as close as possible,” Singleton recalls. “And that’s what they did.”

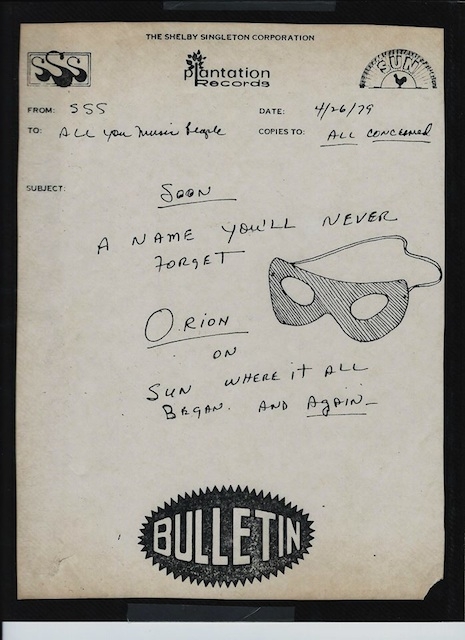

Singleton had a plan. “I put the record out on Sun Records without a name on it,” the record company owner recalls, a devilish twinkle in his eye. “Everybody came back and swore that I had some long lost Elvis tracks, that I found them in the Sun vaults and rereleased them.”

After Singleton had bought Sun Records several years before, he made several moves that drew the ire of RCA Records, the company that bought the rights to Elvis Presley’s music from Sam Phillips in 1955 for $35,000. RCA pressed several lawsuits against Singleton, most of them involving the Sun label’s reissuing of early Presley songs and the release of the “Million Dollar Quartet” album, which featured old, previously unreleased studio tapes of Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash.

When RCA heard the Jimmy Ellis recordings, it too thought Singleton had dug up more lost Elvis tapes. “RCA came very close to suing me over the record,” Singleton says. “I kept telling them it wasn’t Elvis, but they didn’t believe me, and they thought I kept a name off the single because it was Elvis…. So they ran a voice print on it. That’s when they found out it really wasn’t Elvis.”

A few years after the release of the single, which encountered some success thanks to rural radio play in the South, Ellis got involved with another record man, Bobby Smith of Macon, Ga. The two collaborated on a couple of singles and an album, Ellis Sings Elvis, that traded off on the singer’s uncanny vocal resemblance to the most famous rocker in the world.

The album was created before Presley’s death. But as Ellis and Smith were preparing to put the album out, Presley passed away at his Graceland mansion. Overnight, of course, the star evolved from a pitiable shadow figure of a once-great artist into the overwhelmingly revered Dead Elvis. Interest in all things Elvis immediately heightened. Smith rushed the Ellis Sings Elvis album onto the market, at the same time contacting Singleton to ask if Sun might want to get involved.

The Mercurial Rising

Teddy Boys praying at a memorial service for American rock singer Elvis Presley at Christ Church Cockfosters, London. Hundreds of fans were locked out of the service forcing a second one to be hastily arranged.

A maverick from the start, the Texas-born Shelby Singleton was among the wave of music executives who came to prominence in the ’60s–unlike Owen Bradley, Chet Atkins, Fred Rose, and other founders of Music Row, he came from the business side rather than the musical side of the industry. He gained his reputation as a free-thinking promoter who often stepped outside of normal business practices.

A former U.S. Marine, he entered the music business in the late 1950s as a regional promoter for Mercury Records. His knack for creative ideas moved him quickly through the Mercury system. By 1960, he was based in New York, eventually becoming vice president of Mercury and then the top executive of subsidiary Smash Records. During his tenure at Mercury, he produced both pop and country acts, most of them Southern-based. His early successes included Brook Benton’s “The Boll Weevil Song” and Lee Roy Van Dyke’s “Walk On By” in 1961, and Bruce Chanel’s “Hey Baby” and Ray Stevens’ “Ahab the Arab” in 1962. He also produced hits for Jerry Lee Lewis, Roger Miller, Charlie Rich, and Dave Dudley in the early to mid-1960s.

In 1966, Singleton left Mercury to form his own production company, SSS International, and eventually his own record label, Plantation Records. In 1968, he scored one of the biggest independent-label hits in Nashville history with Jeannie C. Riley’s recording of a Tom T. Hall song, “Harper Valley P.T.A.” The single sold 4 million copies, and the accompanying album more than 500,000 units. Flush with cash from that success, Singleton purchased Sun Records from Sam Phillips.

In the years that followed, he stayed busy conceiving outlandish ways to repackage Sun recordings, all of which allowed him to keep selling the same famous songs over and over again. But his business plan had one major stumbling block: He only had access to a limited number of recordings by Sun’s biggest stars, which, besides Presley, included Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, and Charlie Rich.

But when Smith contacted him about Jimmy Ellis, Singleton was skeptical about the singer’s potential. Nonetheless, he agreed to meet with the two men. In the meantime, in true enterprising fashion, he began to wonder if Ellis might sound like Elvis even when singing material that Presley never recorded. So when Ellis and Smith arrived for the meeting, Singleton took the singer into the studio. They cut the classic song “Release Me,” as well as several other songs that Presley hadn’t ever recorded. Listening to those recordings now, it’s obvious that Ellis managed to resemble Presley’s vocal tone and mannerisms more than other sound-alikes and imitators. “It sure sounded like Elvis to me,” Singleton affirms.

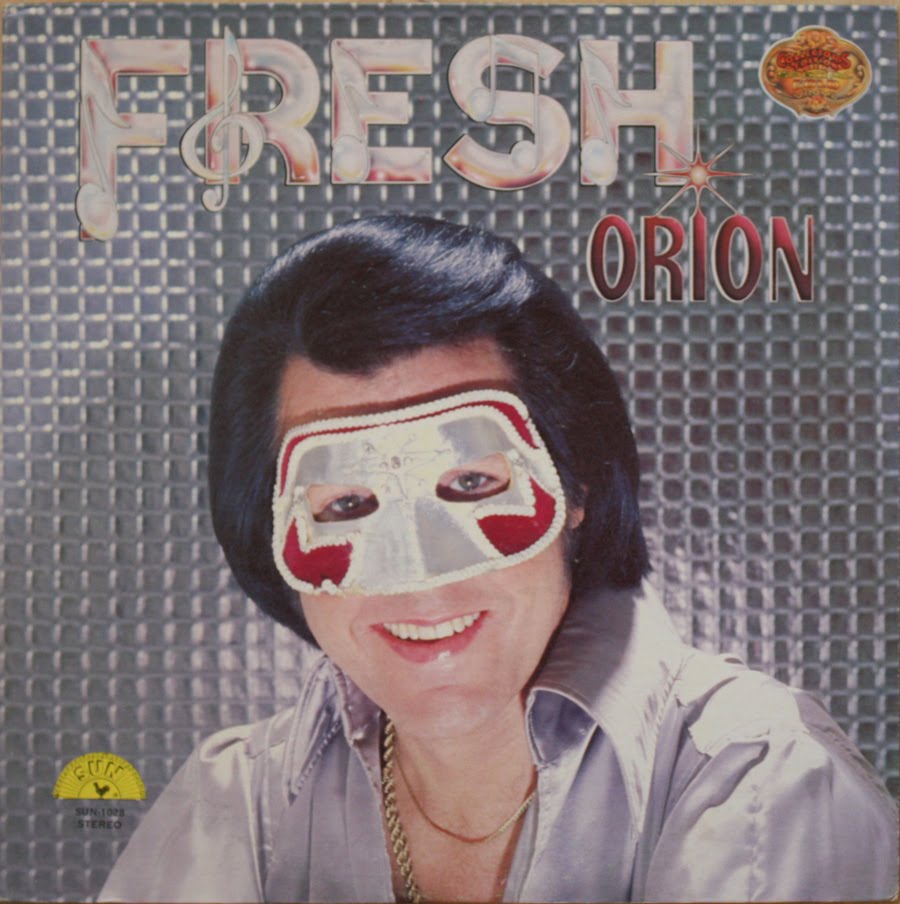

Drawing on his legendary ability to scheme up unique record promotions, the producer felt the wheels of invention start to turn inside his crafty head: Surely there must be some way to make money off this Southern farm boy, with his jet-black hair and long sideburns. Looking back, Singleton says he only wanted to help Ellis come up with an attention-getting persona–and, of course, to make some money for both of them. “He wasn’t an imitator, he was a sound-alike,” Singleton stresses. “I thought we could do something with him if we came up with an angle that was unique.”

Already, Singleton realized that he needed to continue stoking the idea that Ellis might actually be Elvis. But instead of simply having him sing covers of Presley songs, he began pairing the singer with Presley’s famous colleagues from the Sun Records era. To start, he took Ellis in the studio and put his voice onto some old Jerry Lee Lewis masters, issuing the recordings as Jerry Lee & Friends, in hopes that people would think the unnamed singer was Elvis Presley.

It worked, at least to some degree. “Immediately after I put it out, it got on the radio and of course everyone thought it was Elvis, that it was something I found in the can,” Singleton says. “We kind of had a reputation for doing weird things anyway.” But there were limitations to the gimmick, since there were only so many Sun masters on which Singleton could add Ellis’ vocal. And that’s when the maverick producer came up with his most brilliant stroke yet.

Orion: The Living Superstar of Song

Singleton had heard about Brewer-Giorgio’s unpublished book, Orion: The Living Superstar of Song. Instinctively sensing an opportunity, he decided to contact the author. “I thought that if I could make a deal with this lady, we can take Jimmy and we can make him over to be Orion.” Of course, there were a few sticking points. For instance, Ellis may have had thick black hair and long sideburns, but his was not the familiar face of Elvis.

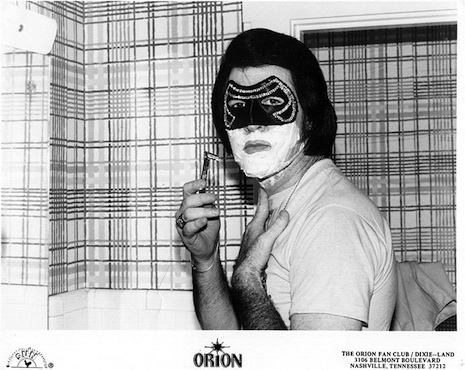

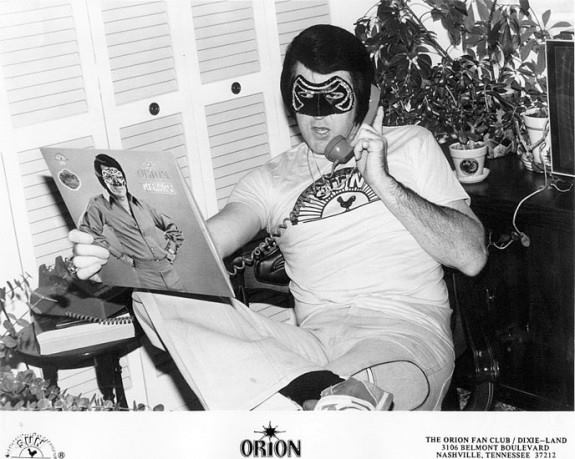

Leave it to Singleton to come up with a plan: “I thought, ‘If he would just wear a mask, we can make him a star,’ ” Singleton says. But Ellis didn’t exactly embrace the idea of spending the rest of his career peering through a mask. “He didn’t really want to do it,” Singleton says, still incredulous at Ellis’ lack of enthusiasm. “I had an artist here at the time that I had to transform in some way to make him famous, and he was resisting. But, looking back, I think he didn’t like it because he figured none of his friends would know that it was really him.”

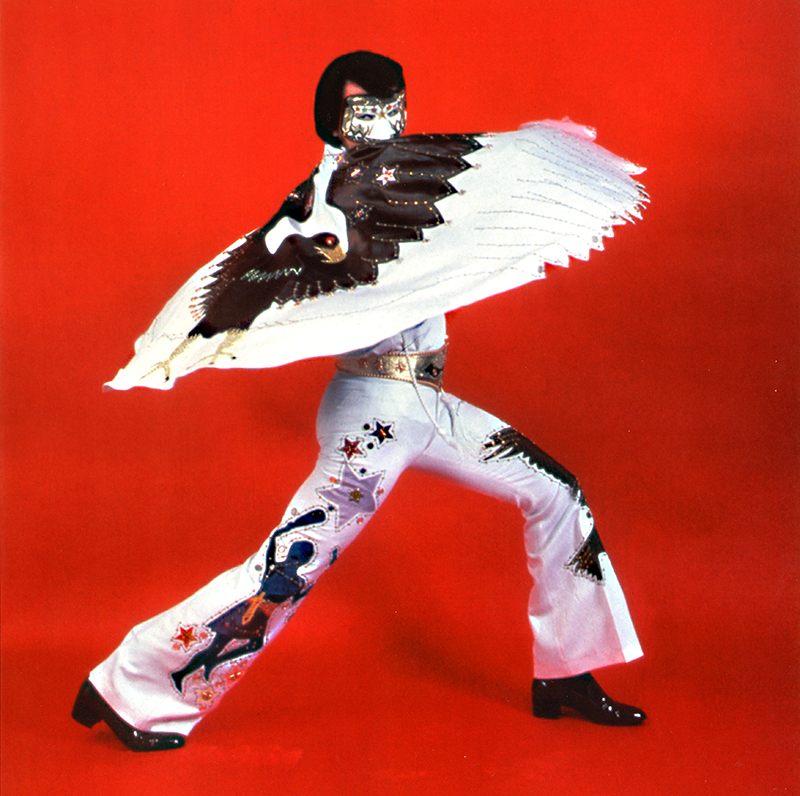

Ultimately, Ellis realized he only had two options: put on a mask and take a chance as the mysterious rhinestone Elvis duplicator, or go back home to Alabama and to 15 years of dead-end attempts at becoming a popular performer. Ellis put on the mask and became Orion…and he was in the building, thank you very much.

Become Elvis

With Orion’s debut, once again, there were those who thought Singleton had unearthed another batch of lost Elvis tapes from the Sun archives. But this time, Singleton went with his original idea of having the singer cut songs Presley had never recorded. In the process, he tapped right into Brewer-Giorgio’s plotline: When people heard this singer who sounded so uncannily like Elvis, perhaps they’d think that he was Elvis, and that maybe the King had indeed faked his death. After all, he hadn’t recorded these songs before.

In the studio, Singleton set up Orion with a full rock orchestra, approximating the dramatic strings-and-horns sound that Presley favored in his later years. The ensemble recorded a sweeping batch of songs, from Skylark’s 1973 hit “Wildflower” to a swinging version of Nat King Cole’s “Mona Lisa.” Singleton emphasized songs packed with drama and pathos, tunes like “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” and “He’ll Have to Go.”

To make sure people made the connection that this enigmatic vocalist mightbe Elvis Presley, Singleton launched Orion’s career with a debut album that featured a closed white casket on the cover. The title: Orion Reborn.

As it turned out, Ellis not only sounded similar to Presley when he sang; his speaking voice also resembled the late singer’s slurred twang. So the first single Singleton issued was a cover of an old Everly Brothers hit, “Ebony Eyes.” The song came complete with a recitation in which Orion assumed the hushed speaking voice of a man who, while waiting in an airport to greet his love, discovers the plane has crashed. “People would hear that recitation and get tears in their eyes,” Singleton says.

By this point, it was time to take Orion to the stage. “We had several different masks made, in different colors and styles and things like that,” Singleton remembers. “The first concert we did was done in a high-school auditorium around Athens, Ala. The place was absolutely packed.”

Orion began touring regionally, mostly in the Southeast and Midwest. “As he started doing more and more radio interviews and local television shows and the like, the tabloids picked up on him,” Singleton says. “They started printing that Elvis was really alive and performing every night as Orion. That’s when it really exploded for him.”

The reverberations were felt worldwide. Not only did Orion perform to crowds of 1,000 or more in the South; he also staged successful tours of Europe, proving especially popular in England, Germany, and Switzerland, where newspapers, magazines, and television interviews showered attention on the Masked Man Who Would Be Elvis.

“It was kind of an easy thing to get press on him, because of all the controversy,” Singleton says. “Needless to say, we sold a lot of records too. We sold records in every country where we could get the record distributed.”

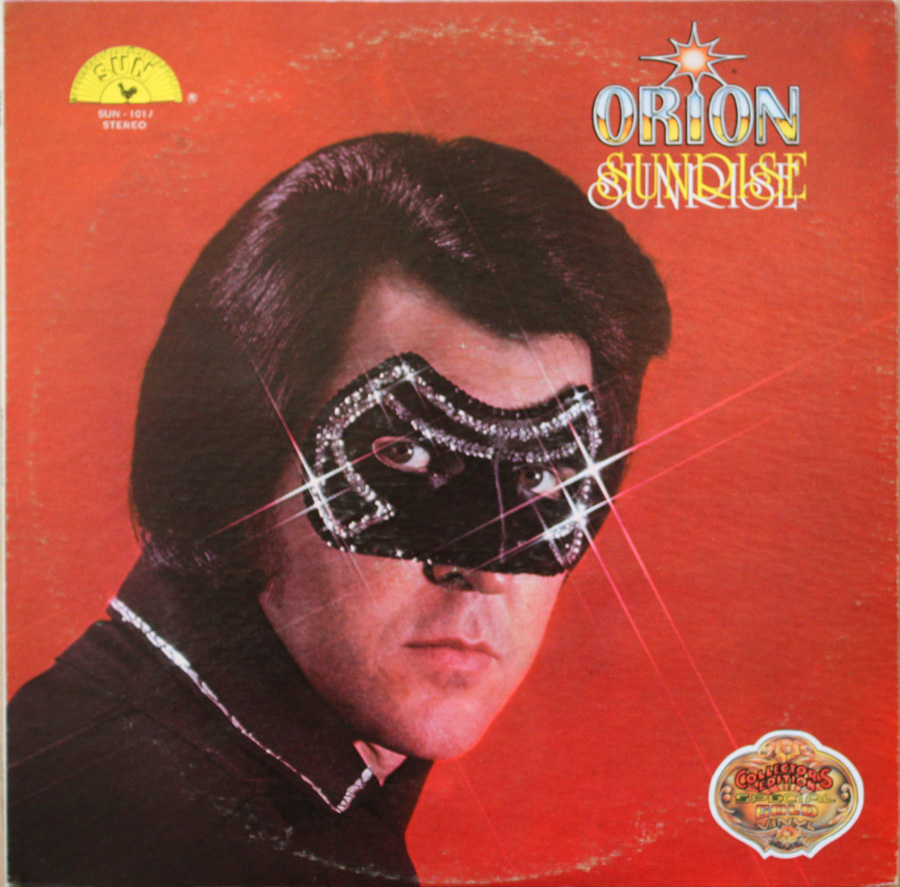

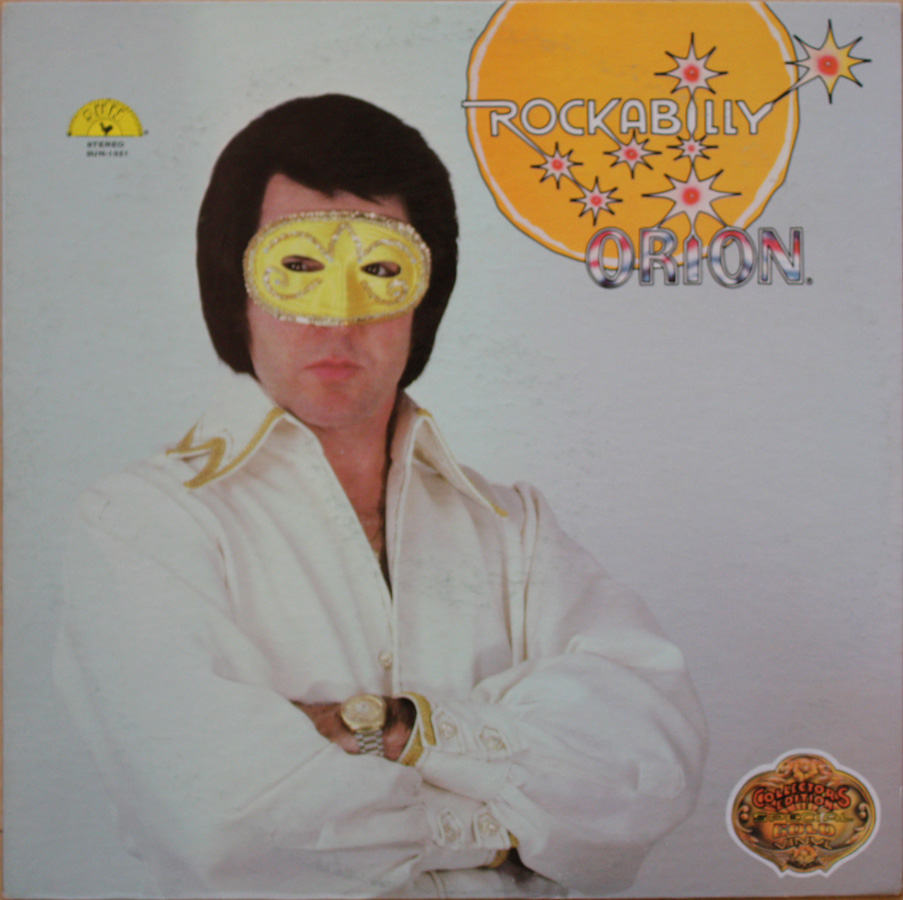

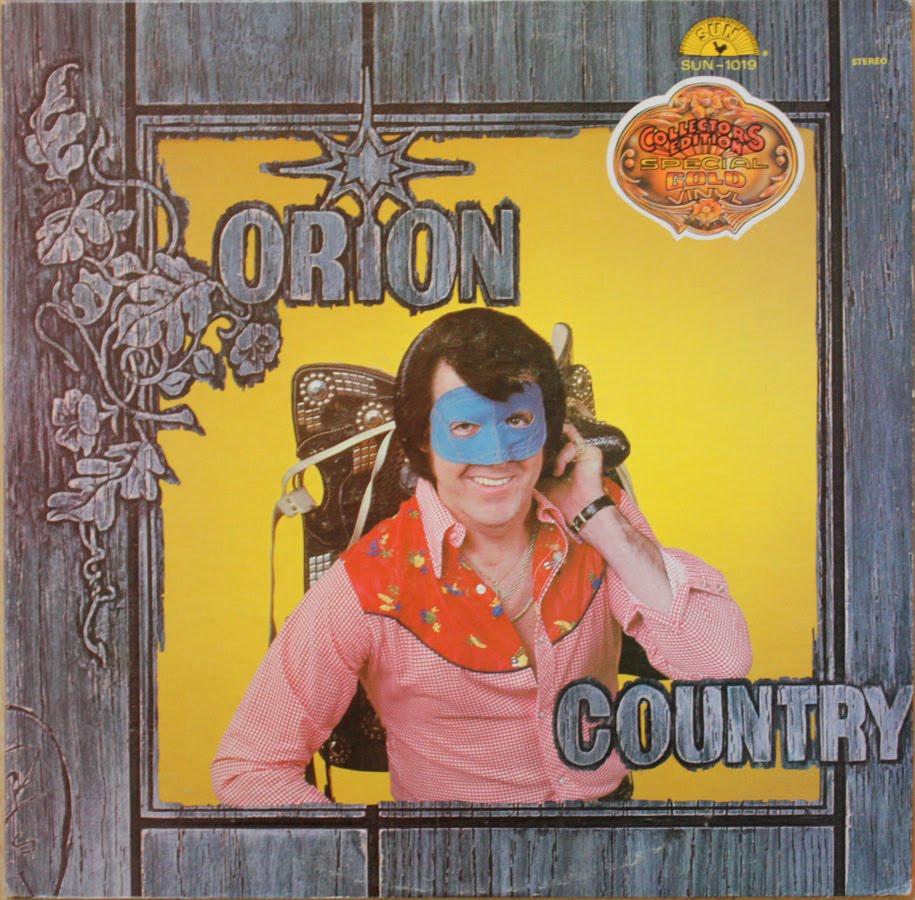

Because some people objected to the casket cover on Orion’s debut, Singleton reissued the record with a new sleeve featuring Orion in a mask, his thick black hair and sideburns combed to look as much like Presley as possible. After that, the albums kept coming in a seemingly unstoppable flood of product. Next was a collection called Sunrise–an overt reference to Presley’s first record label. Then Singleton had Orion create a series of albums in which he covered famous songs in a specific genre. There wasOrion Rockabilly, Orion Country, a collection of gospel songs titled Orion Glory, and an album of love ballads, Feelings. In all, there were nine albums in three years, and they all sold decently enough to keep Singleton coming up with new angles and schemes.

“I think at one point we had 15,000 fan club members,” Singleton says. “We could guarantee any promoter that at least 500 people would show up at any gig, because there were that many people who were following him around the country. Wherever he was playing, they were there. There were hundreds of people in different parts of the country who would travel 500 miles, 1,000 miles, or whatever to see every show they could see. You’d see the same people at every show.”

The most extreme of the fans were a mother and daughter who lived in a car in the parking lot behind the Sun Records building on Belmont Boulevard. When Orion’s bus took off, the duo followed, buying tickets at each show and sitting as close to the stage as possible. They’d occasionally disappear, only to return again, sometimes following Orion nonstop for months at a time.

Fans with special prayer sheets at a memorial service for Elvis Presley held in London three days after the singer’s death, 18th August 1977. (Photo by John Downing/Getty Images)

Singleton’s theory was that scores of people desperately wanted to believe that Presley hadn’t died, and he was more than happy to exploit that desire. “They really hoped that in some way Elvis could still be alive,” he says. “They wanted to believe so badly. I think that’s why Orion had the kind of following he had.”

In retrospect, it’s hard to imagine that people could have actually believed Elvis Presley was still living, cloaked in the guise of Orion. After all, this is the stuff of crackpot conspiracy theories. And yet the fact that fans latched onto Orion only underscores the incredible power of the Presley myth. And in this particular case, the tale of death and rebirth weirdly mirrors that of another, truly religious icon of Western culture.

It was no doubt a heavy and psychologically taxing burden for Jimmy Ellis to shoulder, and the whole charade started to gnaw at him. On one hand, he’d achieved a measure of the success that he’d always dreamed of attaining. On the other hand, he couldn’t even fully savor it. He heard the applause, but he had to realize it was for the ghost he was resurrecting. Like a character in a Shakespearean tragedy, the conflict burning inside of him only loomed larger the longer he tried to suppress it.

Ellis started talking incessantly of retiring his mask, but the perks of his ersatz stardom were difficult to give up–and that only made the dilemma all the more unresolvable. “After he became Orion, he had women all over him all the time,” Singleton says. “He became hooked on women. He got married at one point, but when he’d take [his wife] on the road, he’d have girls in two or three other rooms sometimes. He’d sneak out of his room and go see the other girls while his wife slept or waited for him to return. They fought a lot.”

Even worse, the role even began to play with Ellis’ very sense of identity. Though he’d grown up on a farm in Alabama, his parents had adopted him from a hospital in Birmingham, Ala. As Singleton tells it, “Jimmy started to do some research, and he came across something that said that Vernon and Gladys [Presley] had some trouble in the mid-’40s and that Vernon had left home for a while. There was this other story that Vernon had spent some time in jail too. So, in Jimmy’s mind, he started to think that maybe he was Elvis’ brother. He thought that maybe he had been fathered by Vernon and put up for adoption.”

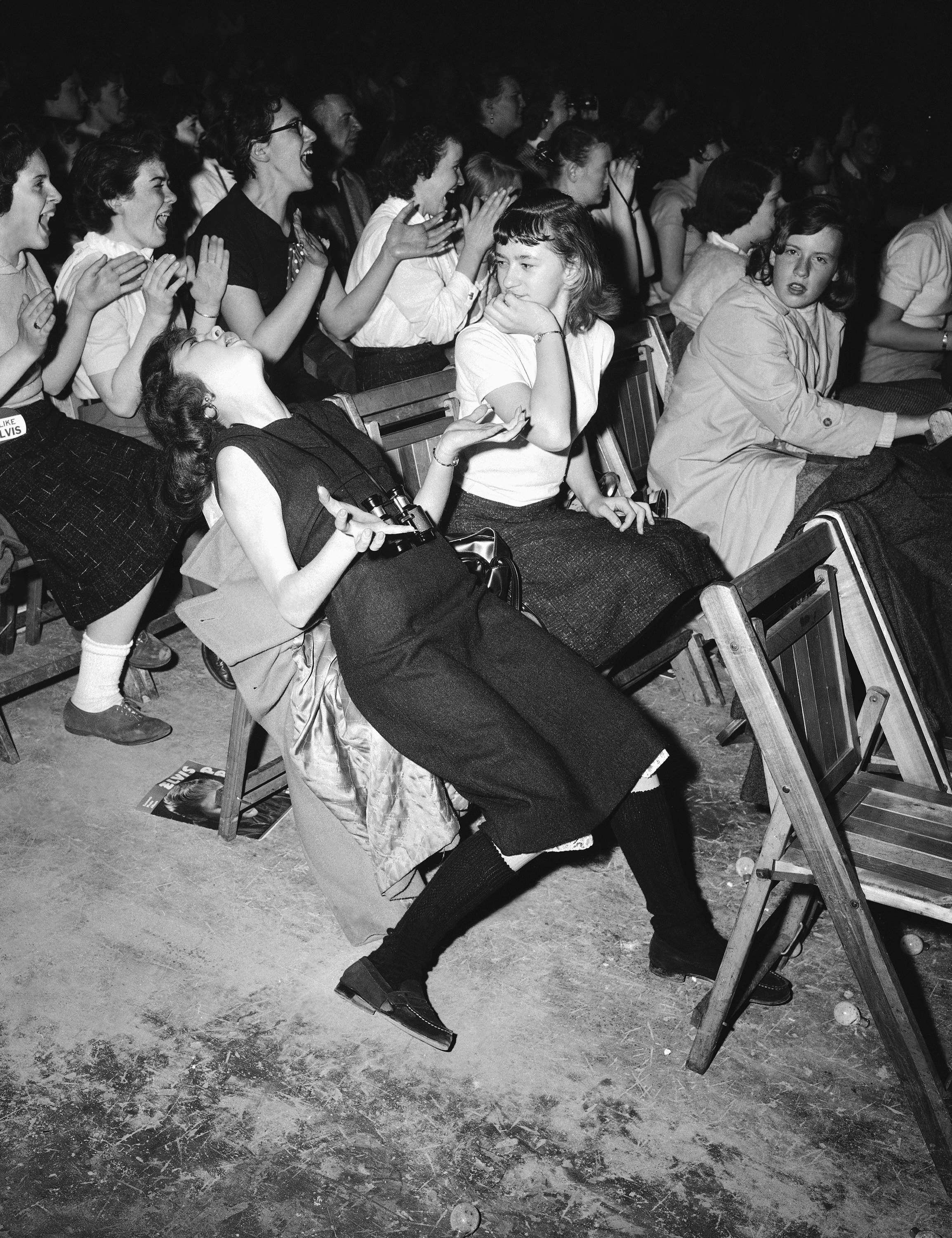

Elvis Fans 1957 This unidentified teenager found Elvis Presley “too much” when he appeared at the Arena in Philadelphia, April 6, 1957.

Ellis and Singleton began to feud. It started with the singer asking politely about recording under his own name, without the mask. Singleton balked, not wanting to risk trading a money-making venture for a dead-end gamble. But as the producer held out, Ellis grew increasingly insolent; Singleton, in turn, grew angry, feeling that his protg didn’t appreciate the success or the wealth he’d given him.

Then, on New Year’s Eve of 1981, the tension reached a head: In mid-performance, Orion ripped off his mask during a dramatic crescendo. A photographer captured the moment; the photos made it clear that the man onstage bore little resemblance to Elvis Presley.

“It exposed who he was, and that ended my gimmick,” Singleton says, frowning. The producer immediately severed his contractual ties with the singer. “I told him, ‘You can do something else, or you can keep on being Orion. I don’t care. I’m not going to fool with you anymore.’ ”

Singleton still expresses disappointment over the parting. “He probably could have been a superstar if he would have listened and taken the guidance he needed,” says Singleton, not one to underestimate his own advice. “But he was like most entertainers. Once you create the image and the act, they get to thinking if it wasn’t for them, this wouldn’t have happened. They don’t realize that the creation of the product is what makes them what they are. They go from the opposite standpoint: They think they’re responsible for the success, not the product and the packaging and all the business that puts them there.”

Singleton may exist on the fringes of the Nashville music industry, but his comments only reaffirm that Orion’s tale is a uniquely Nashville tale–one in which the business of music somehow ends up becoming greater than the very sound of music. Elvis may always be associated with the Bluff City, but his doppelganger was clearly a creation of Music City, a town where careers are made and broken and, of course, reborn.

Elvis Leaves The Building

After Singleton and Ellis parted ways, the Sun Records chief was flooded with calls. “Back then, there were probably 100 Elvis imitators out there, and they all tried to contact us to see if we could do something similar with them.” But by that point, the magic–or whatever it was–was gone.

“I told them no. It was a different deal. Jimmy wasn’t an Elvis impersonator. He just happened to sound like Elvis. Of course, nobody believed that. He was always called an impersonator, because of the way he sounded. But…he was just being himself, and we put a mask on him and called him Orion.”

Ellis, meanwhile, continued to record and perform as Orion. He even began to record covers of Presley’s hits, to dress in bejeweled jumpsuits, and to act and move more like Presley onstage. In other words, the man who wasn’t an Elvis imitator started to become one. For years, he continued to make his living on the road and to find different backers who would help him record and distribute albums. In the mid-1980s, he still drew crowds of a few hundred people in some outposts, mostly in rural Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee.

By the ’90s, Ellis was performing fewer than 50 shows a year. He spent most of his time on a farm near Selma, Ala., that he inherited from his parents. Because the land was near a highway, Ellis opened several small stores–a liquor store, a convenience market, a gas station–to serve travelers and locals.

In a 1990 interview with Rick Harmon, a small-town newspaper reporter in Alabama, Ellis expressed disappointment at ever taking on the guise of Orion. “I just wanted to perform, to use the talent that I had,” he said. As the years wore on, Ellis continued to distance himself from his fictional persona, and from the entertainment business as a whole. Last year, he performed fewer than a dozen paying shows, most of them in Europe. He spent most of his time working at his stores in Selma.

If he was never completely able to leave behind his bizarre recording career, at least he had attained a degree of peace about it. But even that was short-lived: On the night of Dec. 12, 1998, Ellis was behind the register at his convenience store when three local teens charged into the store brandishing sawed-off shotguns. The gunmen shot the 53-year-old Ellis, his 44-year-old fiancee Elaine Thompson, and a friend, Helen King. Ellis and Thompson were killed; King was severely wounded but has recovered. Ellis was survived by his son Jimmy Ellis Jr.

After a career paying tribute to a man who led such a glorified life, Jimmy Ellis’ own existence ended abruptly, violently, unfairly. If there’s any kind of parallel to Elvis here, it’s that death is rarely ever reasonable–and yet it unifies us all in the most definitive way. And even if Orion doesn’t inspire the kind of posthumous hero-worship that Elvis Presley does, it’s clear that his talents have regardless survived him.

The man who turned Jimmy Ellis into Orion grants one thing: The singer truly was a gifted vocalist and a charismatic performer. “He really was good,” Singleton says. “I think he could have been a star on his own, except he was burdened by the fact that, no matter what he did, he sounded like Elvis. That’s a shame, but it was something he couldn’t do anything about.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.