“Nowhere does one come to know an artist better than in his prints [and] the woodcut is the most graphic of the print processes”

– Ernst Kirchner

Fancy owning art the Nazis considered ‘degenerate‘? Won’t someone think of the children, the censors wail, as they viewed German artist Ernst Kirchner’s expressionist paintings. Before we get to Kirchner (6 May 1880 – 15 June 1938), American author Judy Blume has something to say about censorship, albeit when it comes to books: “Censors never go after books unless kids already like them. I don’t even think they know to go after books until they know that children are interested in reading this book, therefore there must be something in it that’s wrong.”

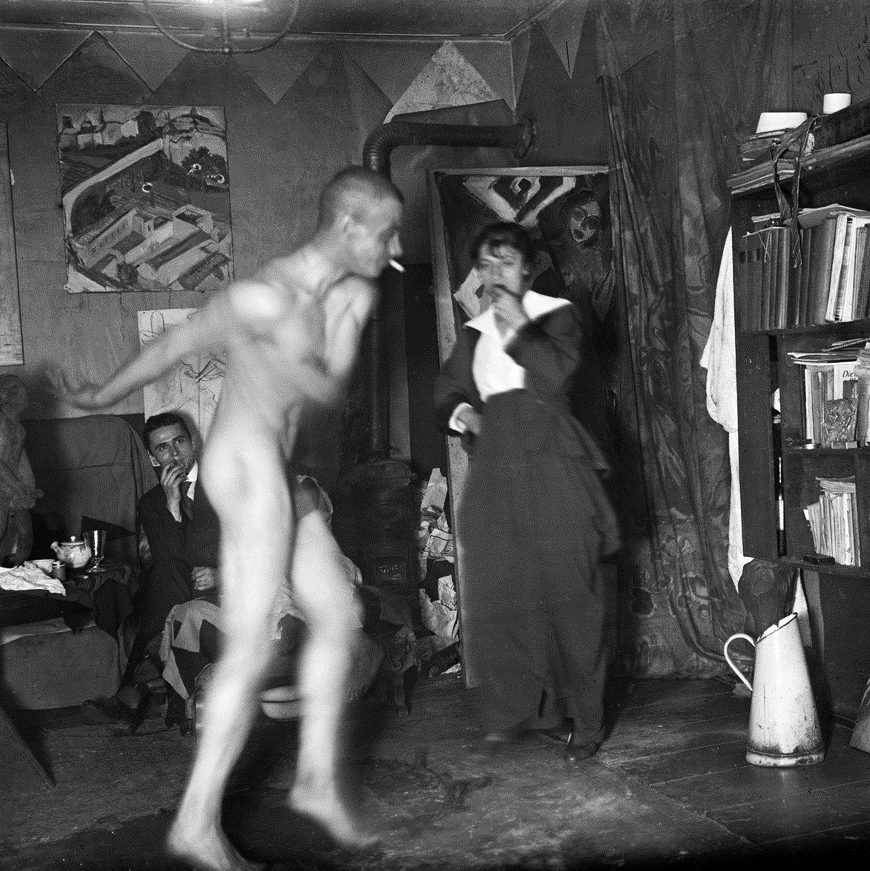

That’s not to says what you about to see is all for all ages. There is a fair amount of nudity, not least of all in these photos of Kirchner in his studio.

Kirchner at home in his studio

Kirchner was a German expressionist painter and printmaker and one of the founders of the artists group Die Brücke or “The Bridge”, a key group leading to the foundation of Expressionism in 20th-century art. He volunteered for army service in the First World War, but soon suffered a breakdown and was discharged. His work was branded “degenerate” by the Nazis in 1933, and in 1937 more than 600 of his creations were sold or destroyed. Some of what’s left is now available as fine art prints in the Flashbak Shop.

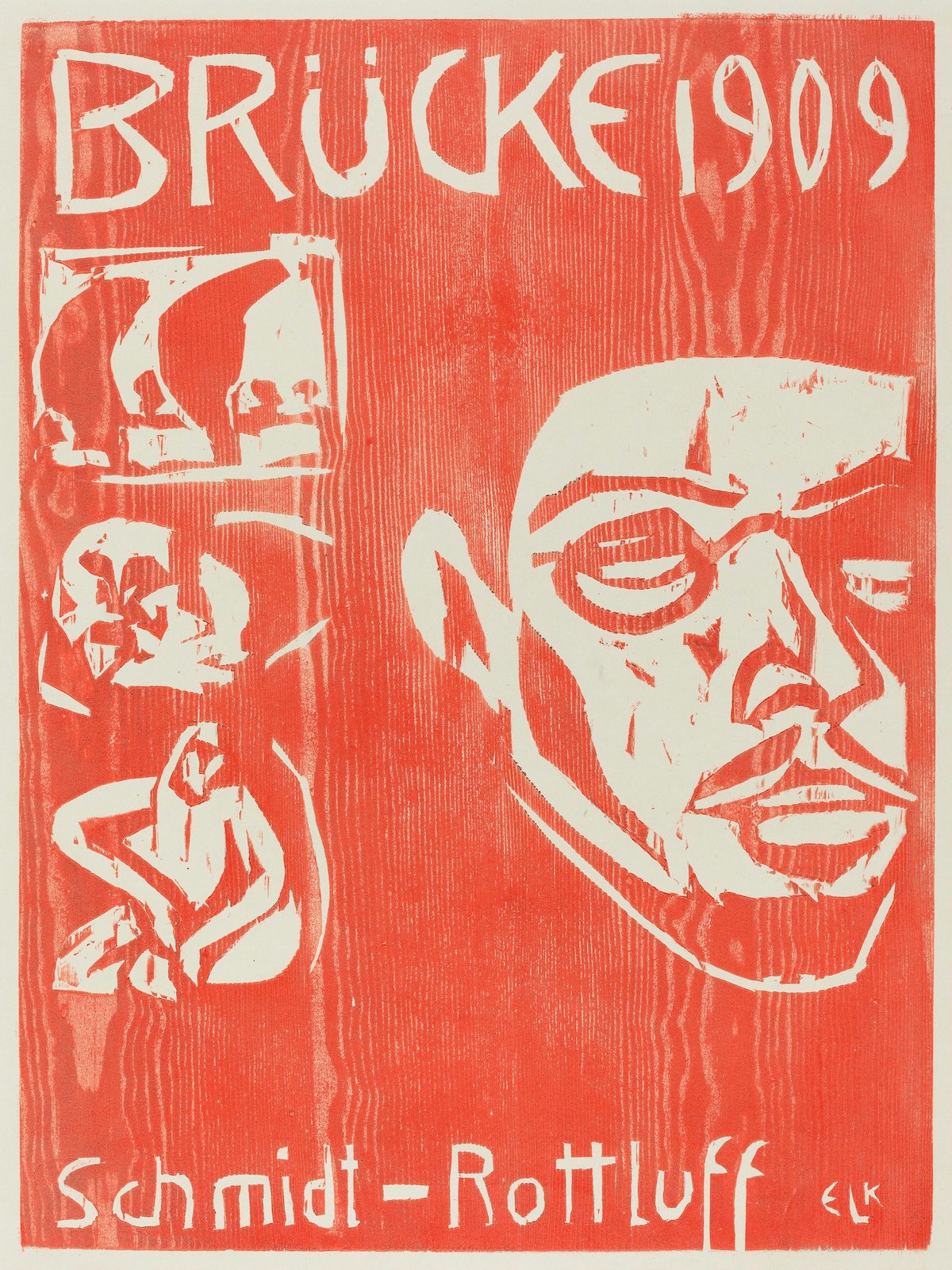

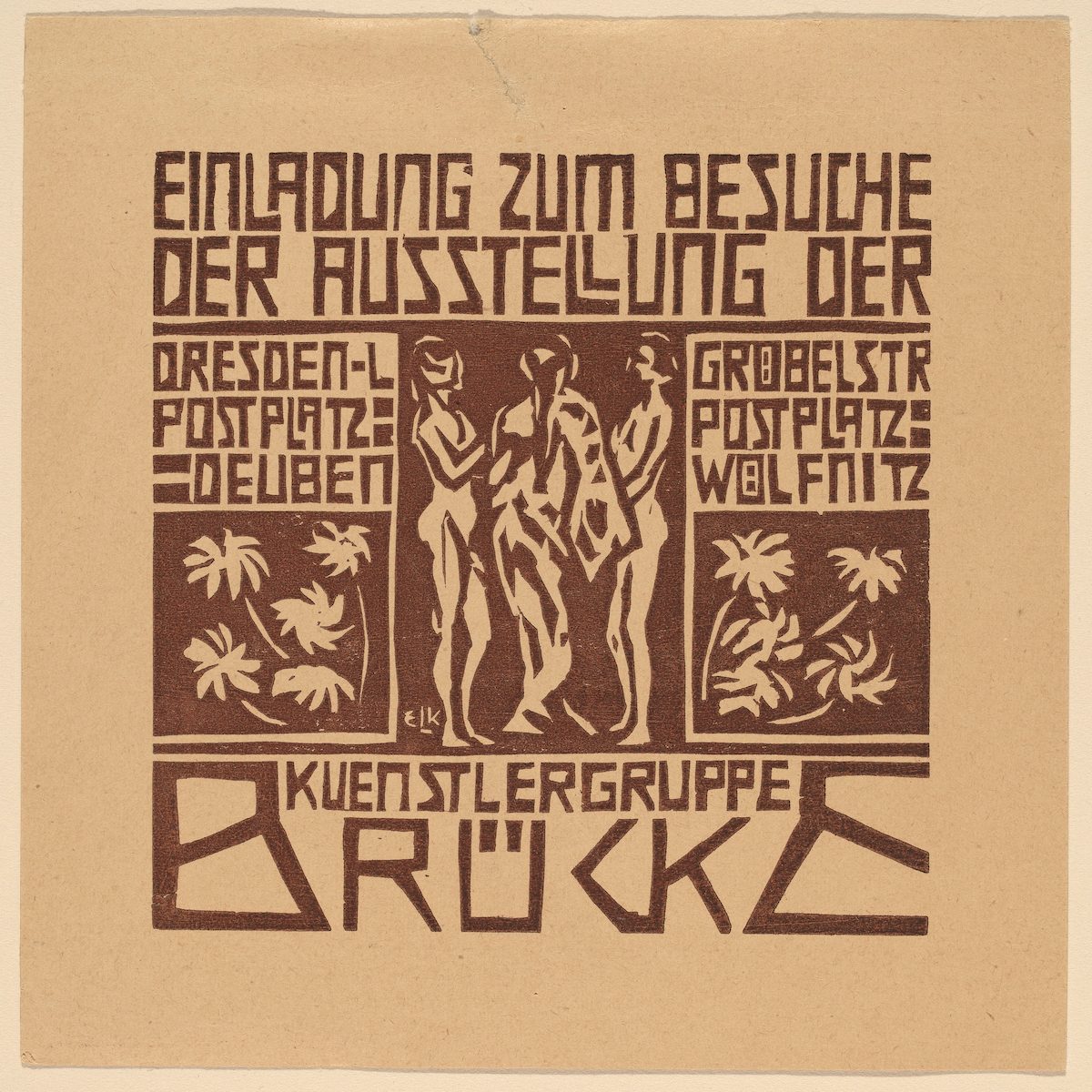

In 1905, Kirchner, along with Fritz Bleyl (8 October 1880 – 19 August 1966) and two other architecture students, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (December 1884 – 10 August 1976) and Erich Heckel (31 July 1883 – 27 January 1970), founded the artists group Die Brücke (“The Bridge”). From then on, Kirchner committed himself to art. The group aimed to eschew the prevalent traditional academic style and find a new mode of artistic expression, which would form a bridge (hence the name) between the past and their time. They responded both to past artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Matthias Grünewald and Lucas Cranach the Elder, as well as contemporary international avant-garde movements. As part of the affirmation of their national heritage, they revived older media, particularly woodcut prints.

Woman Tying Her Shoe (Frau, Schuh Zuknopfend) by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1912 (buy the print)

Then war came. And the drugs and the drink. As Adrian Searle writes, Kirchner is “the absinthe-addled expressionist drew himself in the grip of a morphine fit; who, feigning madness to get himself out of the German army in the first world war, suffered a breakdown and spent months shuttling from sanatorium to sanatorium…By 1918 Kirchner was a physical and nervous wreck, a burned-out case who had to put himself back together again (but, perhaps, never quite did). The National Socialists went on to brand him a degenerate, and there are still Brits who condemn him to a polite mediocrity. Little wonder he eventually shot himself, in 1938.”

So much for the anguish. Another portrait comes via Eberhard Grisebach, who visited Kirchner in March 1917, writing to Helen Spengler of the artist’s condition and brilliance:

“I spent two mornings with Kirchner which I shall never forget. I found him sitting on a very low chair next to a small, hot stove in a yellow-painted, sloping-roofed attic. Only with the help of a stick was he able to walk, staggering around the room… A colourfully painted curtain concealed a large collection of paintings. When we began to look at them, he came alive. Together with me, he saw all his experiences drift by on canvas, the small, timid-looking woman set aside what we had seen and brought a bottle of wine.

“He made short explanatory remarks in a weary voice. Each picture had its own particular colourful character, a great sadness was present in all of them; what I had previously found to be incomprehensible and unfinished now created the same delicate and sensitive impression as his personality.

“Everywhere a search for style, for psychological understanding of his figures. The most moving was a self- portrait in uniform with his right hand cut off. Then he showed me his travel permit for Switzerland. He wanted to go back to Davos… and implored me to ask father for a medical certificate…

“As the woman with him rightly said, though many people want to help him, nobody is able to do so any longer… When I was leaving, I thought of Van Gogh’s fate and thought that it would be his as well, sooner or later. Only later will people understand and see how much he has contributed to painting”.

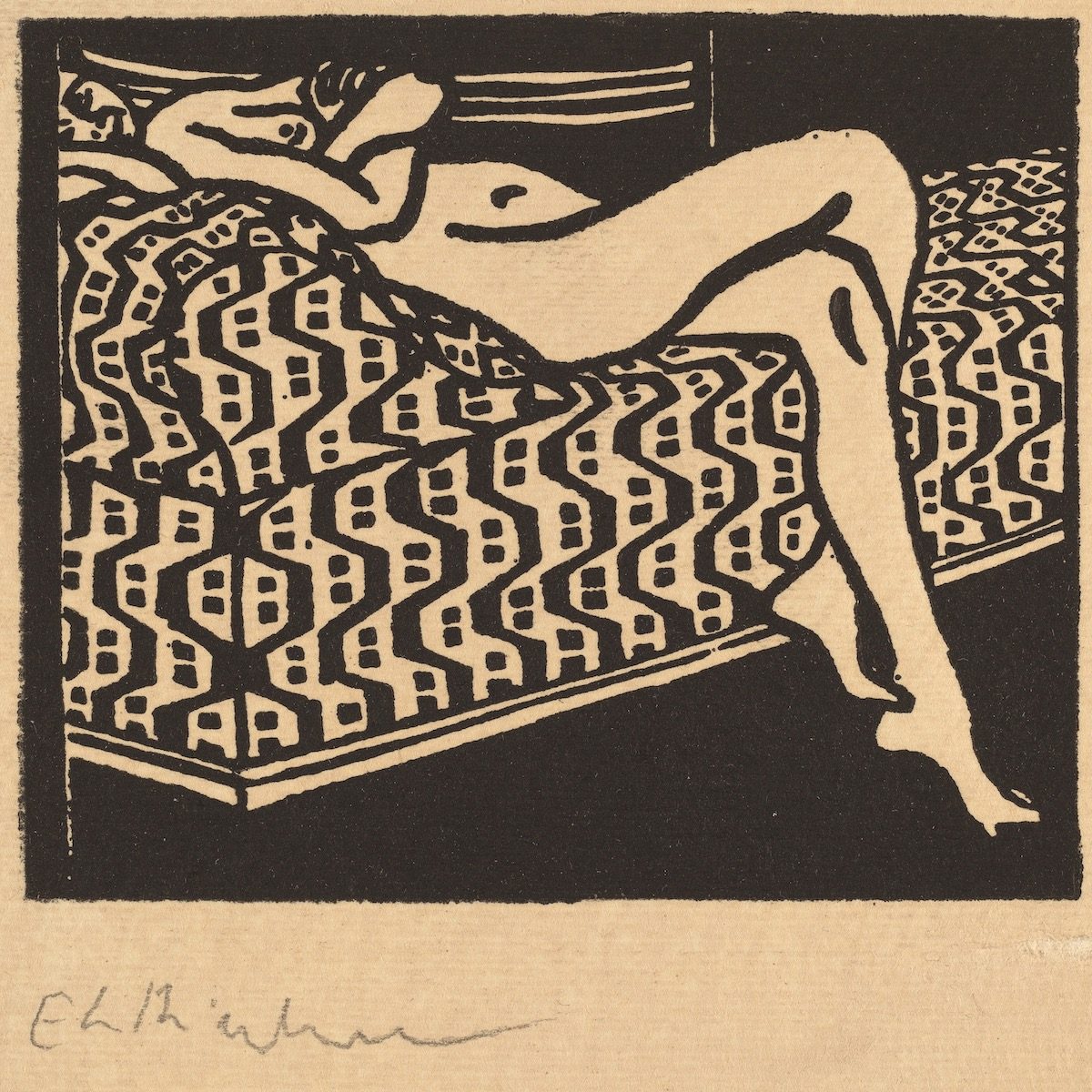

Nude Girl Lying on a Sofa by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1905 (Print)

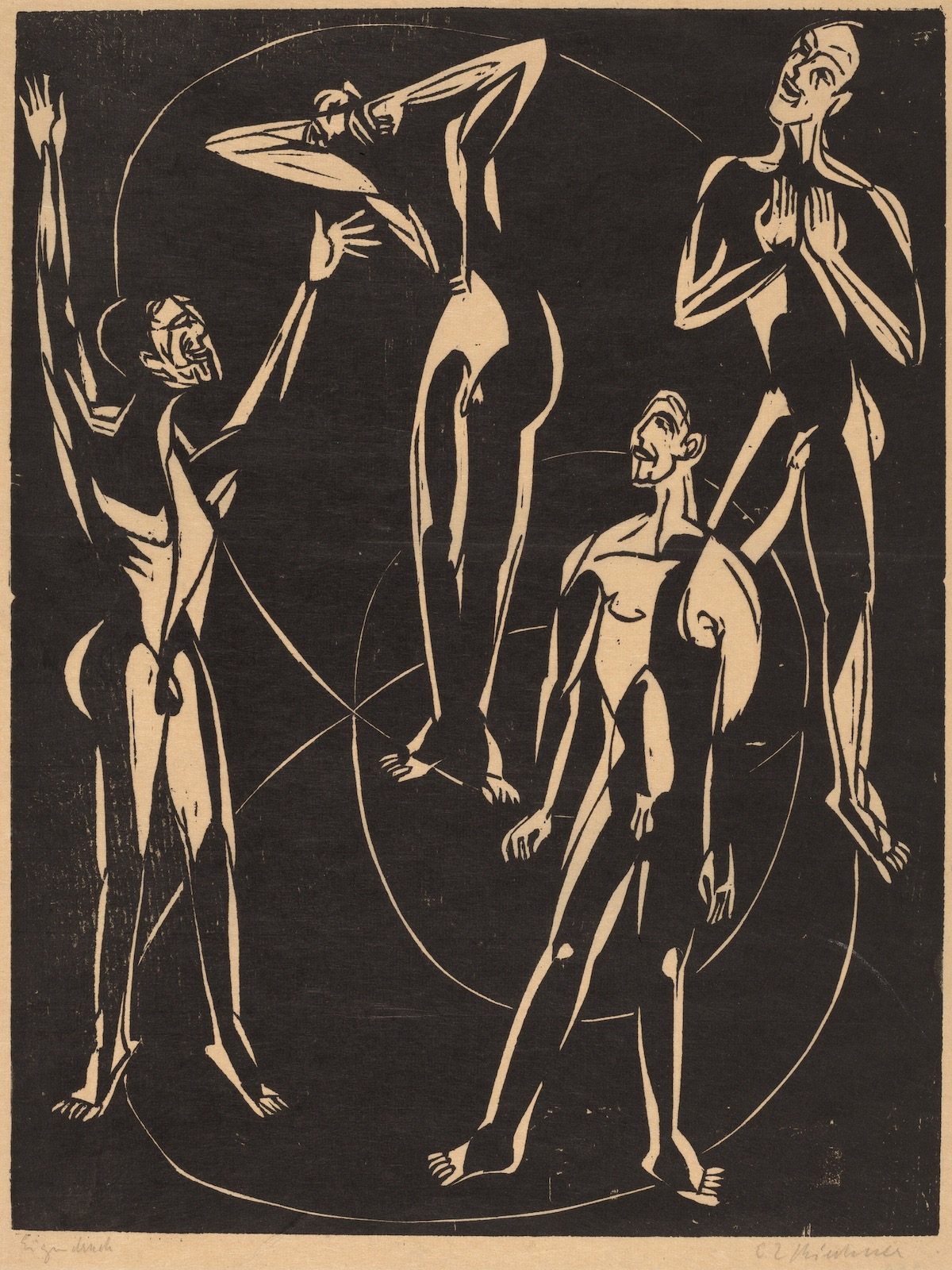

Acrobatic Dance by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner German – 1911 (Print)

Bern Kunsthalle, März 33, Davos, by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1933 (Print)

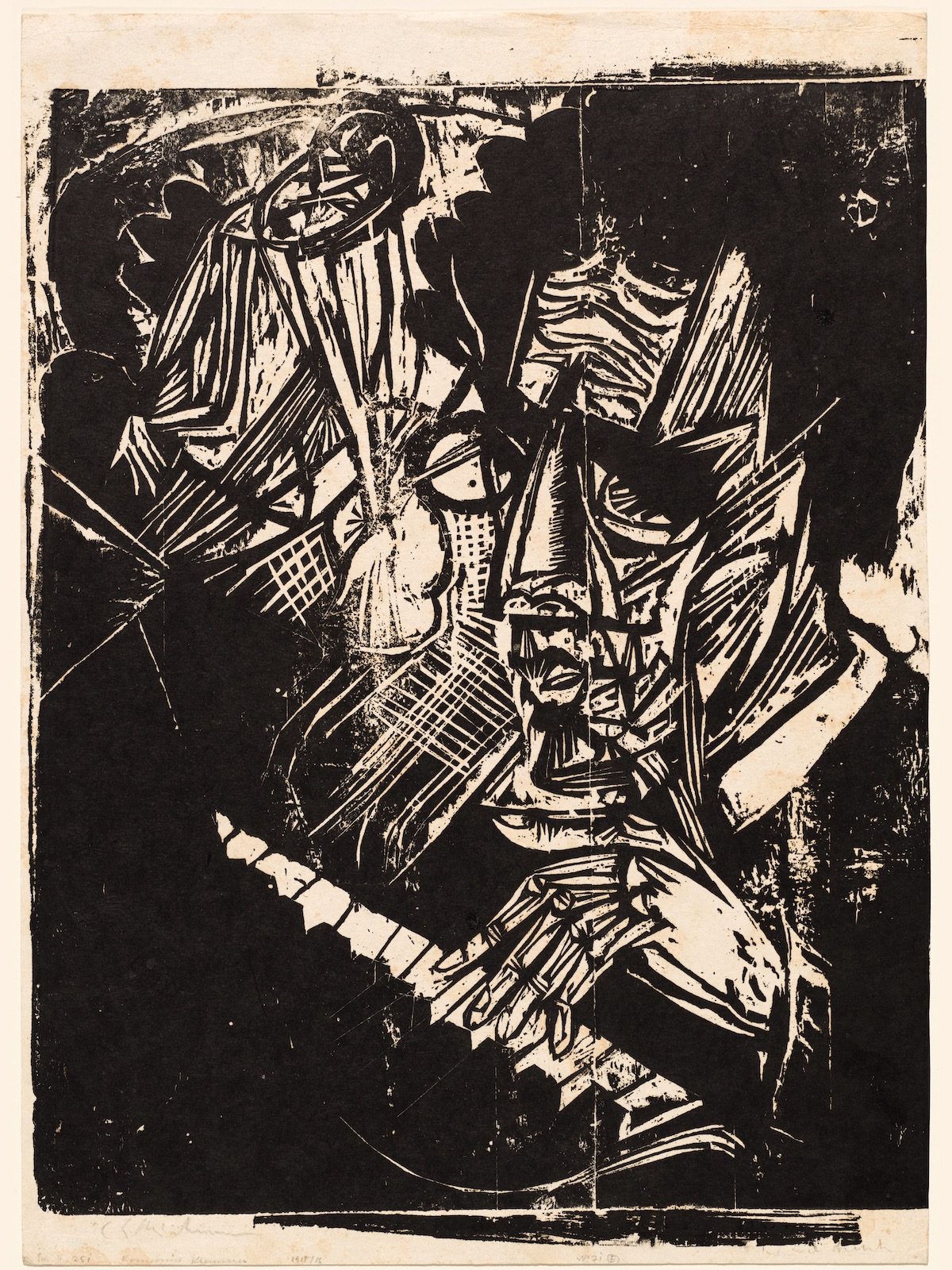

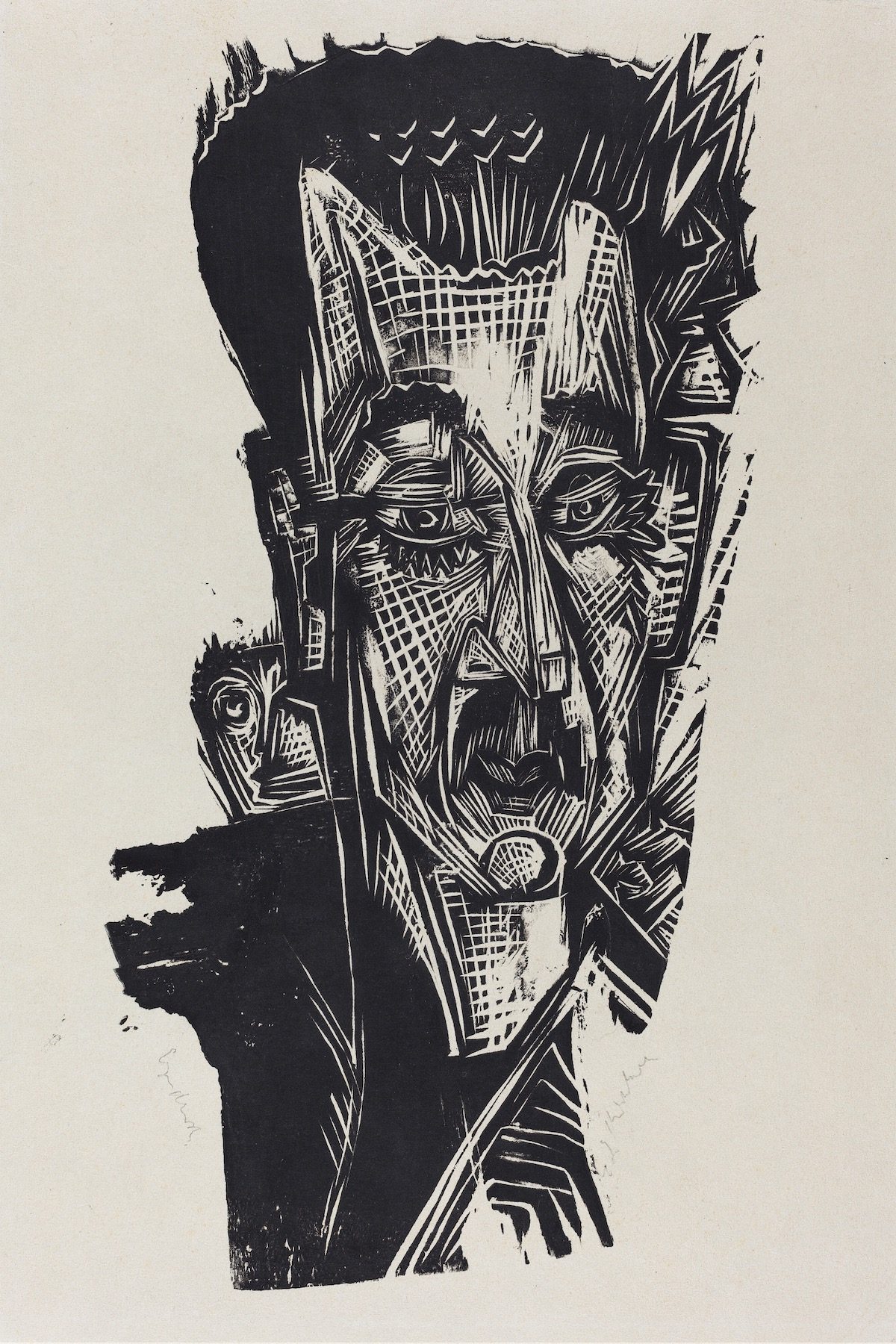

Composer Klemperer by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1916 (Print)

Dr. Ludwig Binswanger by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1917 (Print)

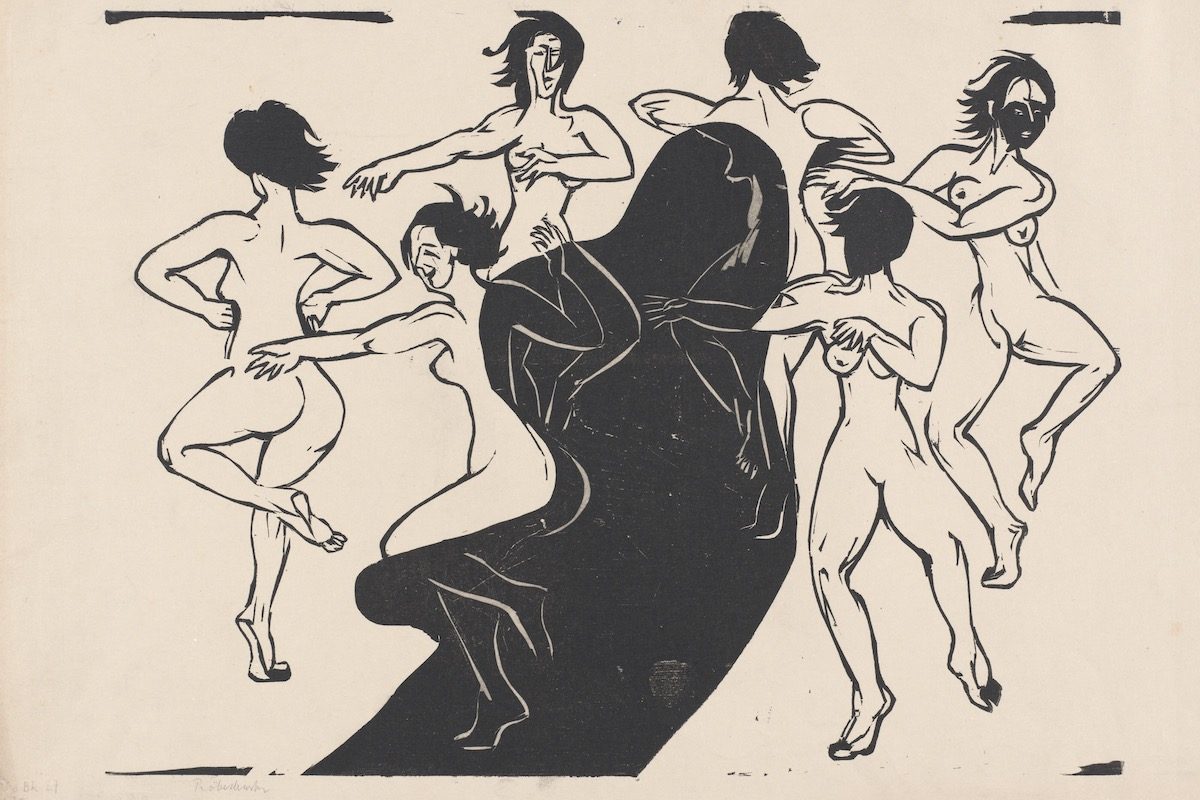

Nudes Dancing Around a Shadow by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1936 (Print)

Nude Dancer by Ernst Ludwig Kircher -1906 – not an early Keith Haring (Print)

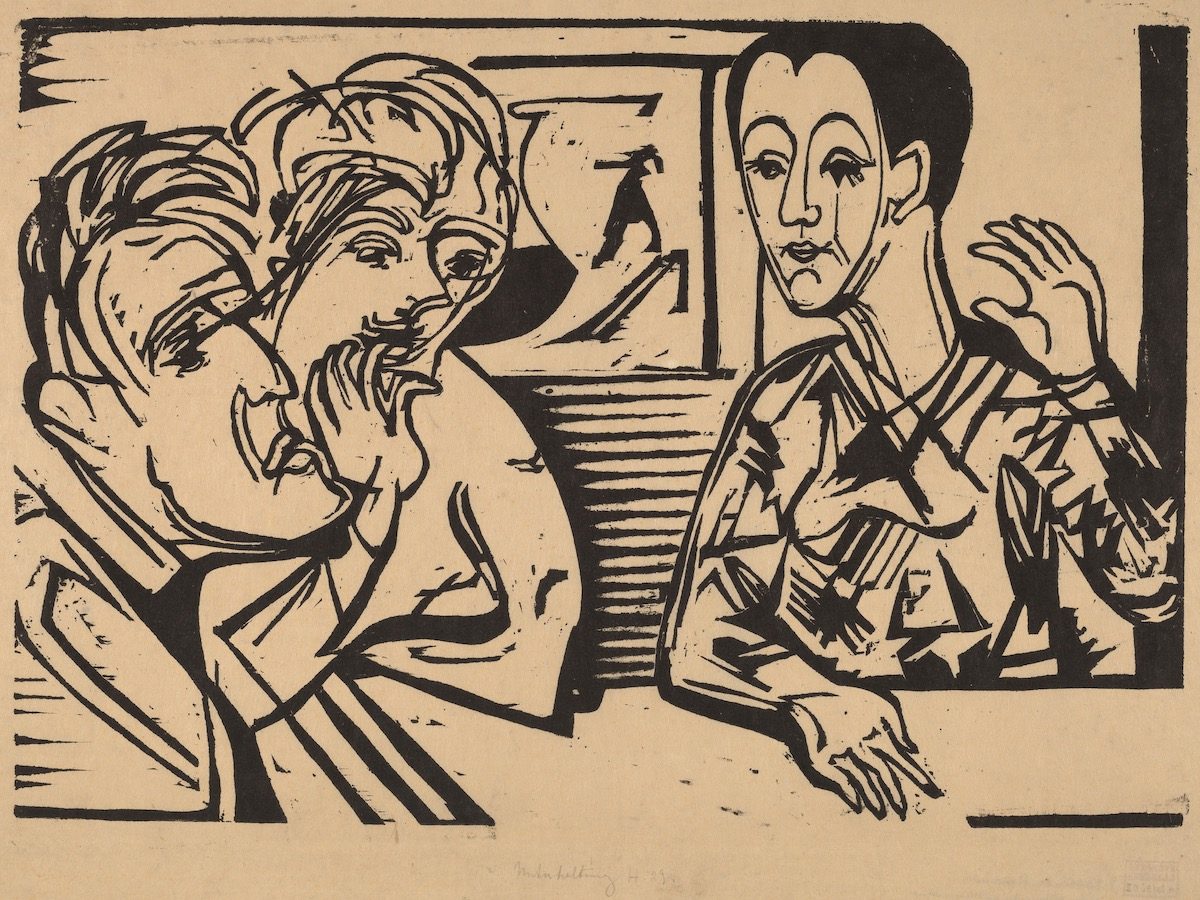

Conversation by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1929 (Print)

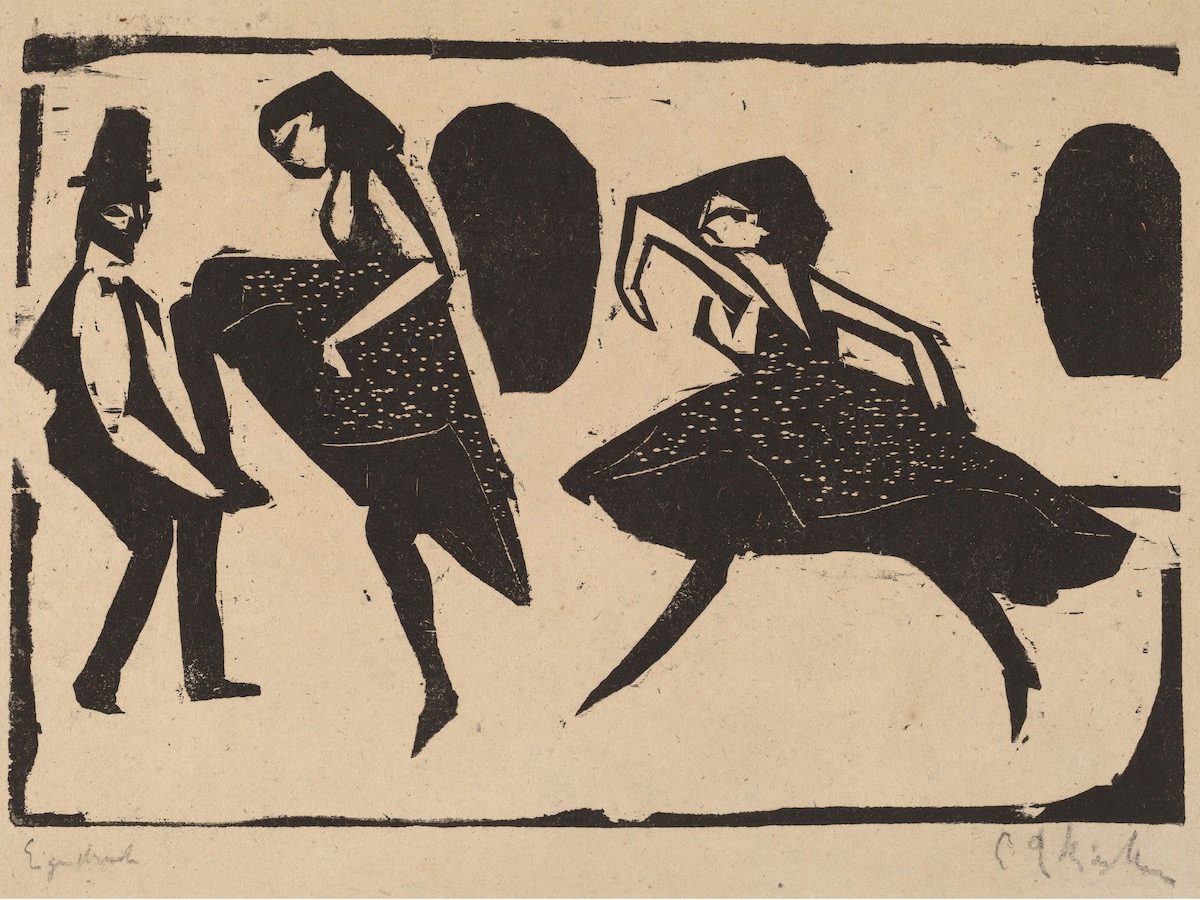

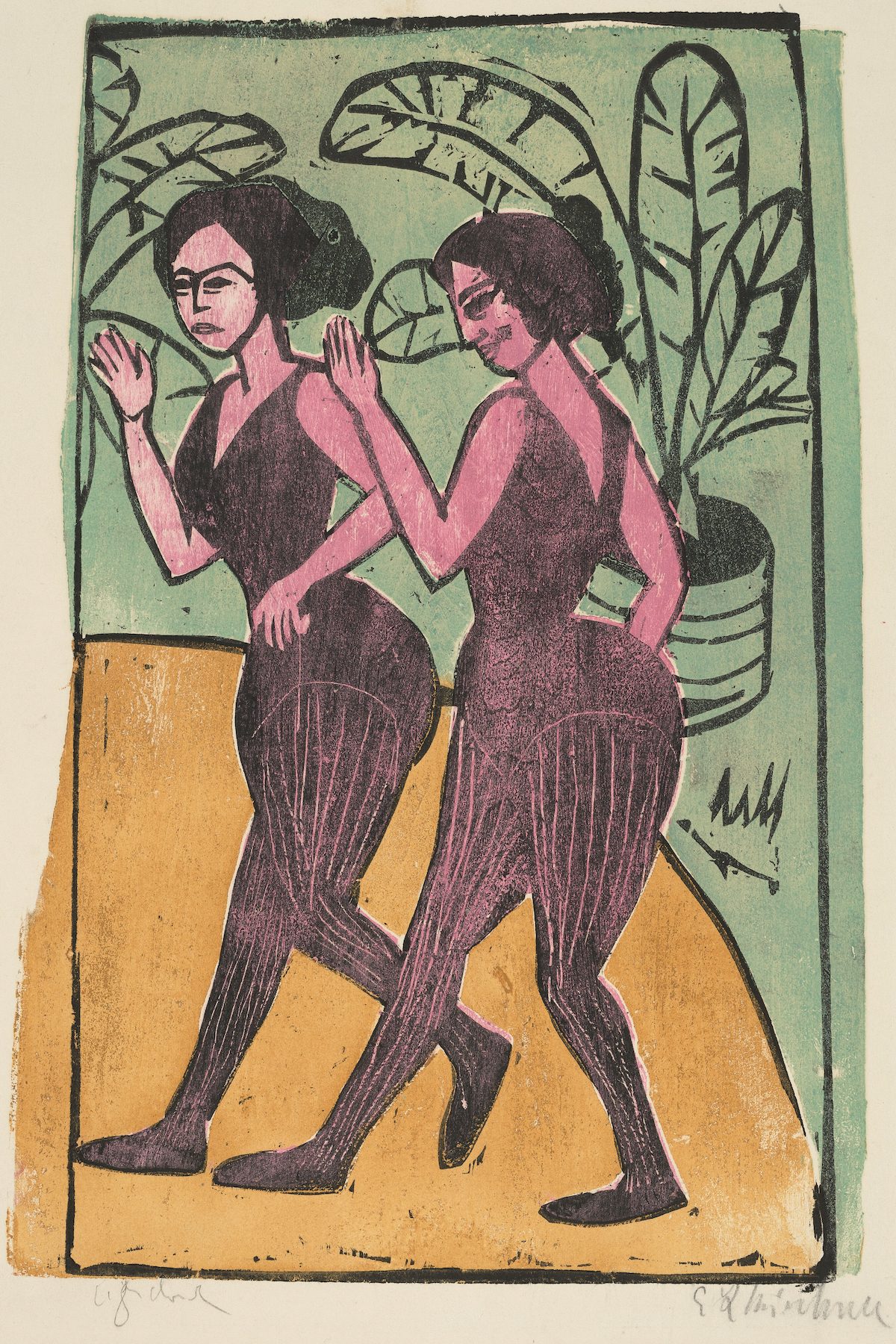

English Step Dancers by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1911 (Print)

Little Variety Act with Singer by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – c. 1909 (Print)

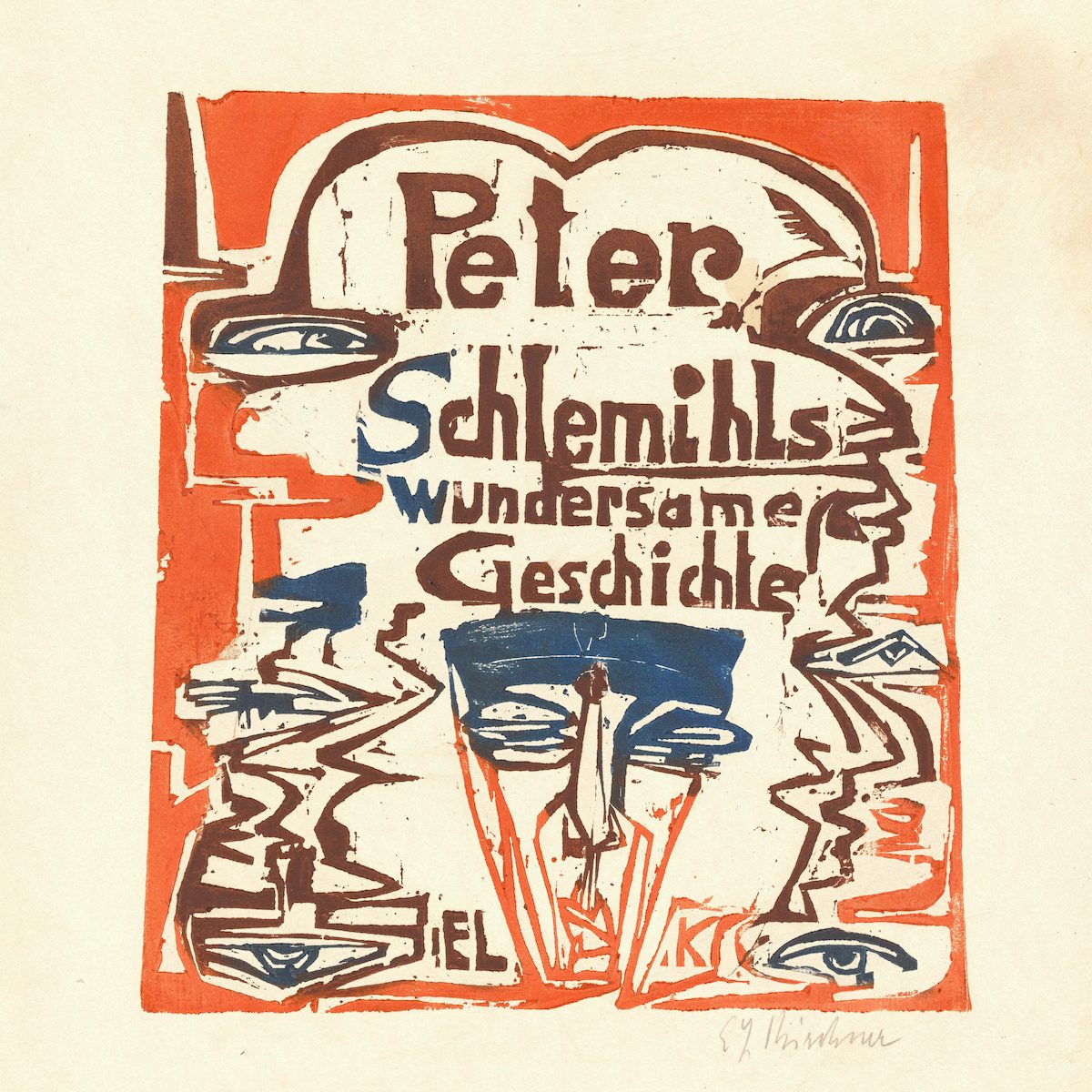

Peter Schlemihls Wundersame Geschichte (Peter Schlemihl’s Wondrous Story) by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1915 (Print)

Cover of the Fourth Yearbook of the Artist Group the Brucke by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1909 (Prints)

Invitation to an Exhibition of the Artists’ Group Brücke by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – 1906 (Prints)

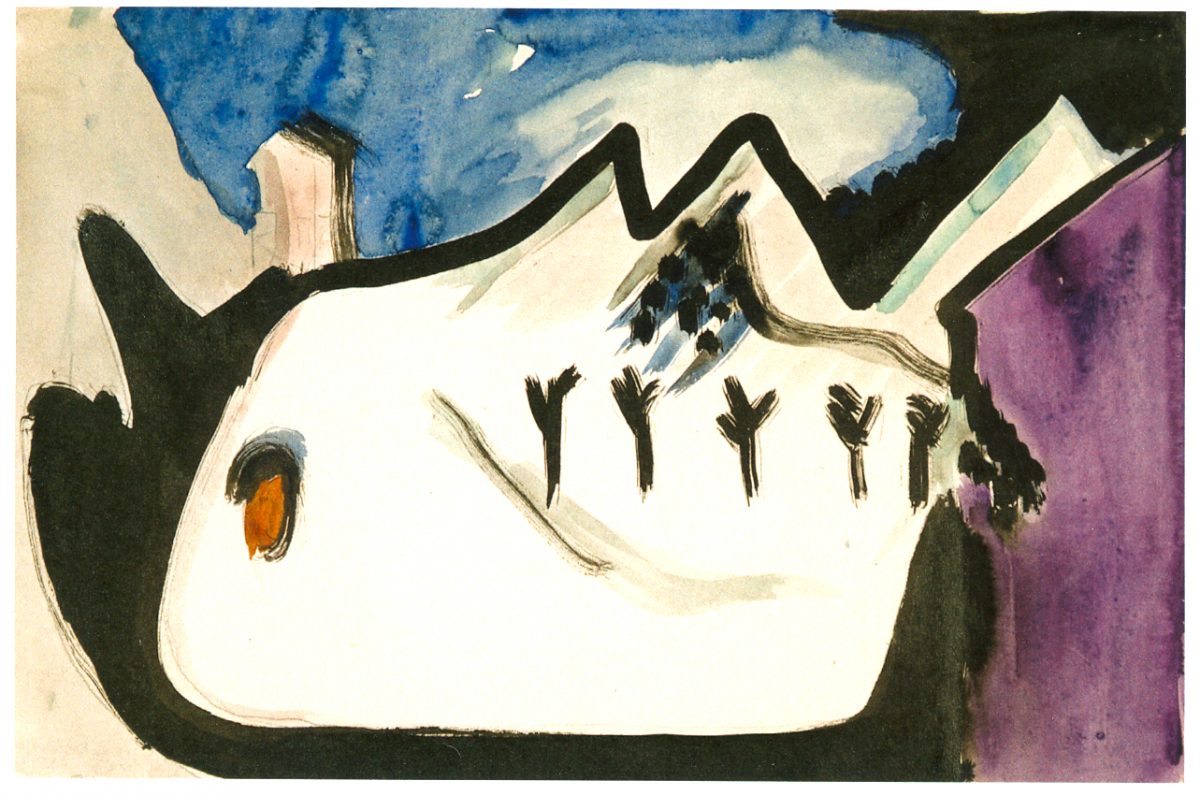

Snowy landscape, 1930

Nudes, ca. 1908, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

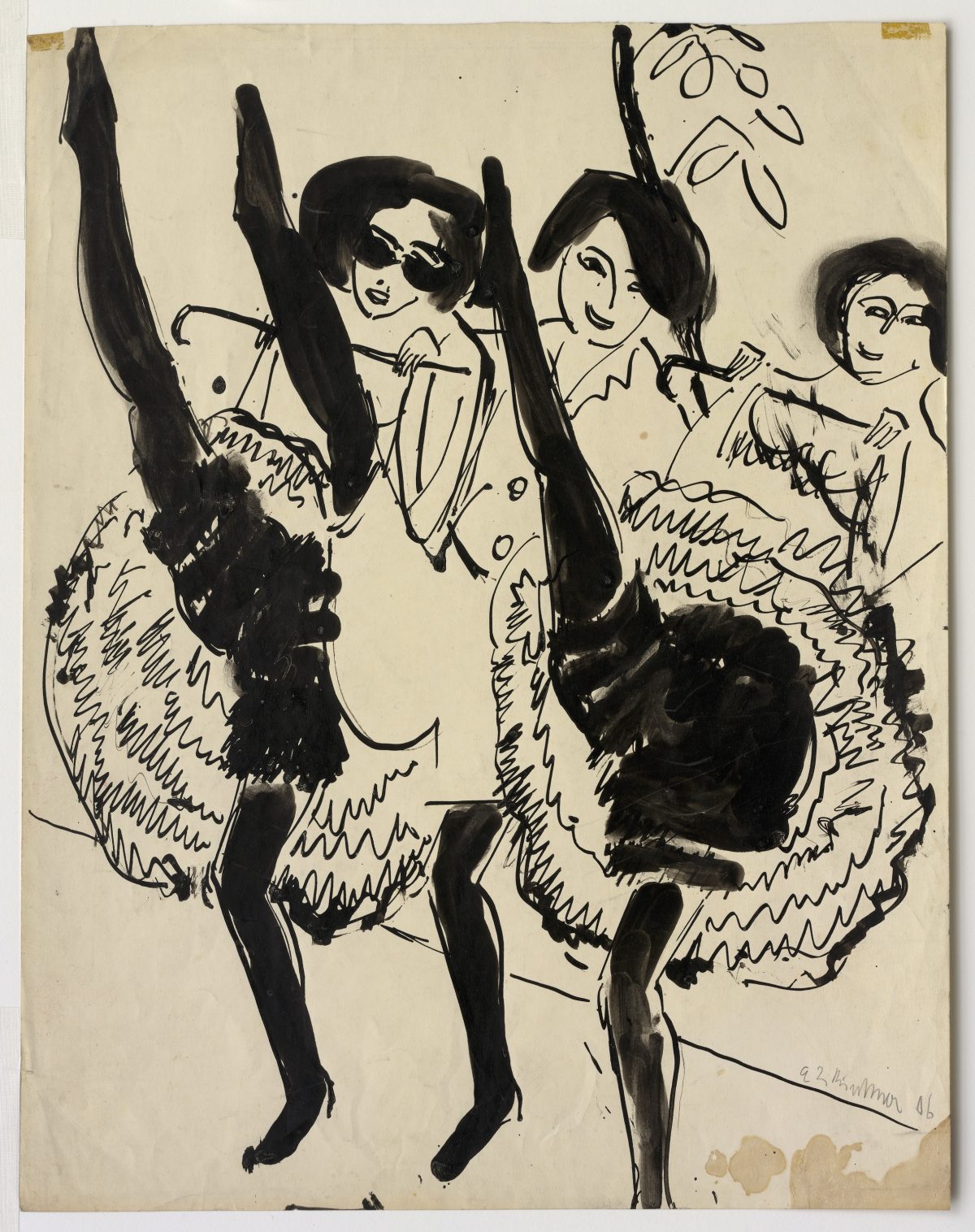

Dancers, 1906, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Moonrise, Soldier and Maiden, 1905, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

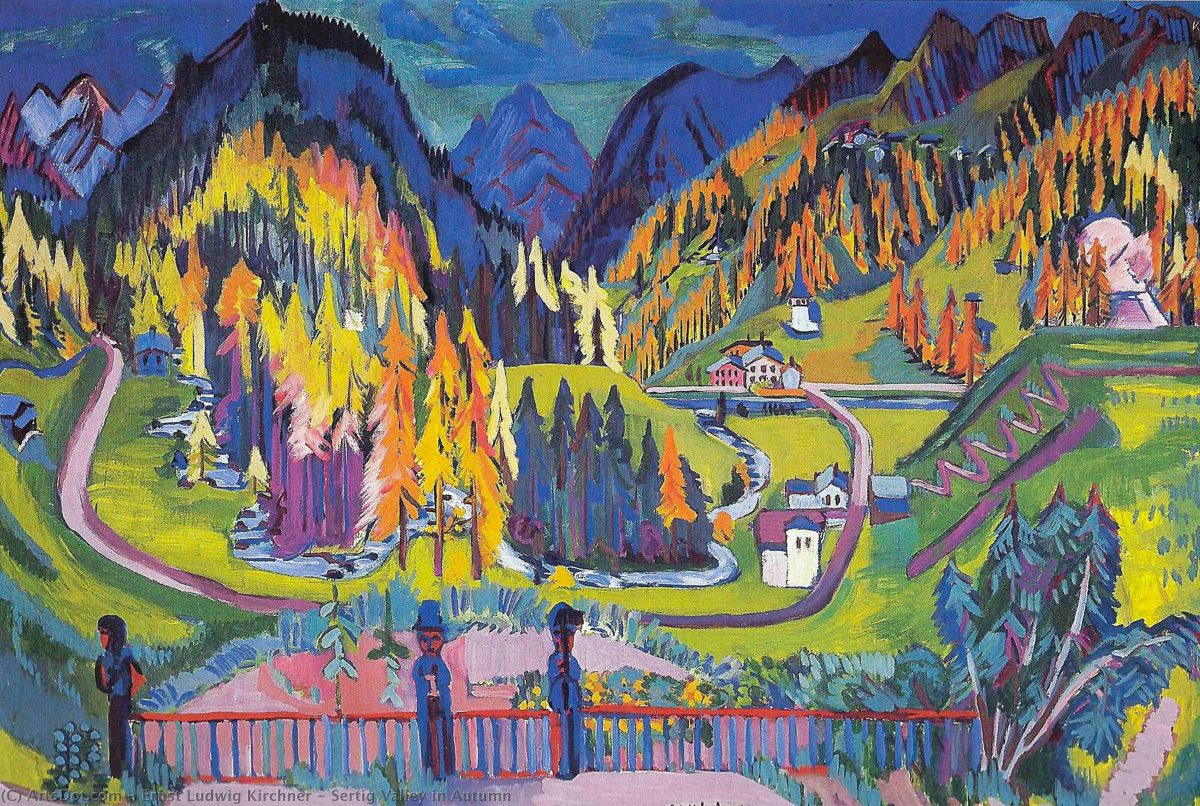

Sertig Valley in Autumn, 1925, Kirchner Museum Davos

Marcella by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Prints by Ernst Kirchner now in the Flashbak Shop. Also T-shirts and more.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.