Even before the accidental 2020 explosion that killed at least 150 and destroyed buildings across half the city, Beirut evoked “dated notions” for most Westerners of decades of explosions in the Lebanese capital, writes Larry Kaplow at NPR: “a 15-year civil war that ended in 1990; a war with Israel and sporadic airstrikes; bombings of the U.S. Marine barracks and the U.S. Embassy; an attack 15 years ago on the prime minister’s convoy.” The city’s name once served as shorthand for the worst conflicts in the Middle East, a symbol of devastation on the scale of London or Dresden during the Second World War.

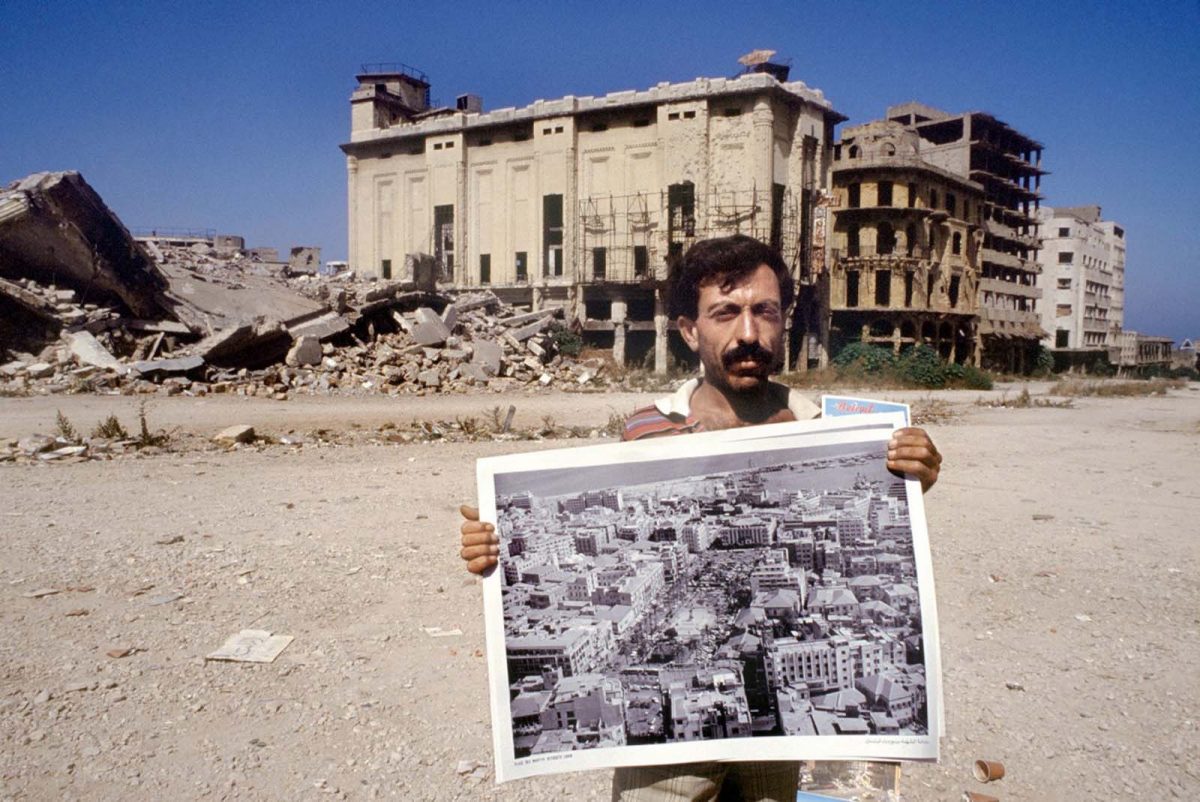

The image was not misplaced. “Not so long ago,” The Washington Post noted in a 2015 article on the rebuilt city, “the historic downtown of Beirut was a wasteland of scorched buildings and rubble. Lebanon’s civil war, which ended in 1990, destroyed an area known for its picturesque Mediterranean vistas and Roman and Mamluk ruins.” The phrase “civil war,” hardly captures the scope of a conflict fought between internal Christian and Muslim groups as well as Syria, Israel, and several several nations. In fact, the worst destruction in the city occurred during the Siege of Beirut in the summer of 1982 when Israeli Defence Forces attempted to drive out the PLO with both targeted and widely indiscriminate bombing.

Even the CIA admits the 70-day siege was “a relentless barrage of air, naval, and artillery bombardment,” resulting in “appalling civilian casualties.” Somewhere around 17,500 Lebanese and Palestinians were killed in the attacks, and around 500 buildings were destroyed. And yet, narratives that the war was principally caused or worsened by outside forces, whether the blame is laid on Israel or Syria, do not accurately characterize the situation. Internal divisions over Palestinian refugees had been growing since 1948, with Muslim and Christian nationalist factions involved on either side.

A Muslim militiaman aims his automatic rifle at Christian forces on the other side of the Green Line in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1982.

Just as its warring factions had a host of competing, even contradictory, agendas, those who remember the Lebanese conflict today are also subject to their ideological blind spots. “Much of public debate about the war since 1990 has revolved around the external/internal question,” writes Middle East historian Haugbolle Sune, “and critical historiography has not been immune to these debates.” Old and new debates aside, the stereotype of Beirut as a center of Middle East conflict is a dated image the city had transcended over time, even if it is now symbol of “neglect on a massive scale,” Kaplow claims.

Yet so much of what has happened in the region and the world since the time can be traced to events of Lebanese Civil War, when “Saudis and Syrians, Iraqis and Libyans, Iranians and Israelis used Beirut as their address of choice to communicate by car bomb,” David Gardner writes at Financial Times (doing so with or without U.S. State Department approval). Historical accounts vary; a material history of the war is also legible in the remains that scarred the city through the 70s, 80s and beyond — and, in some cases, were left untouched as memorials during the 21st century rebuilding.

The Holiday Inn, above, became a notorious image of defiance during the so-called “war of the hotels,” in which the rightwing Christian Lebanese Front and PLO-backed National Movement fought to claim the hotel as a strategic asset in the early months of the conflict in 1975. “The Holiday Inn represented an affluent time for the city: the building became part of a luxury development bubble at a time when Beirut’s banks were growing fat on deposits from the region’s petrodollars,” writes Moe-Ali Nayel. Now, “bullet-ridden and rocket-pierced,” it remains, “a front-line, a demarcation between east and west, and a symbol of war.”

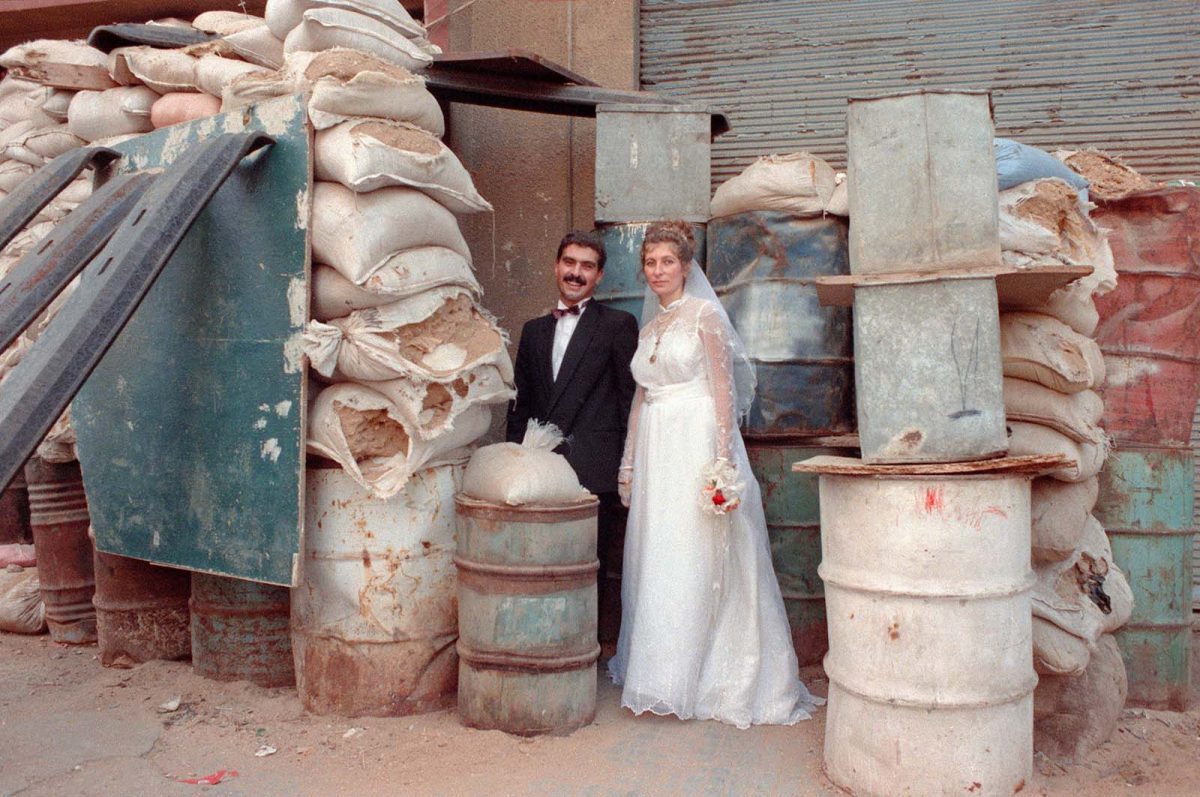

Photography alone cannot tell these stories; but neither can journalism or critical history. It resonates in Lebanese novels like Elias Khoury’s Yalo (2009) and Rawi Hage’s De Niro’s Game (2006); in the memoirs like those of journalist and former teenage soldier Yussef Bazzi; and in the aftermath of August 4, 2020, when a tragic accident produced images almost uncannily indistinguishable, except for cars and clothing, from photographs of Beirut during its 15-year Civil War.

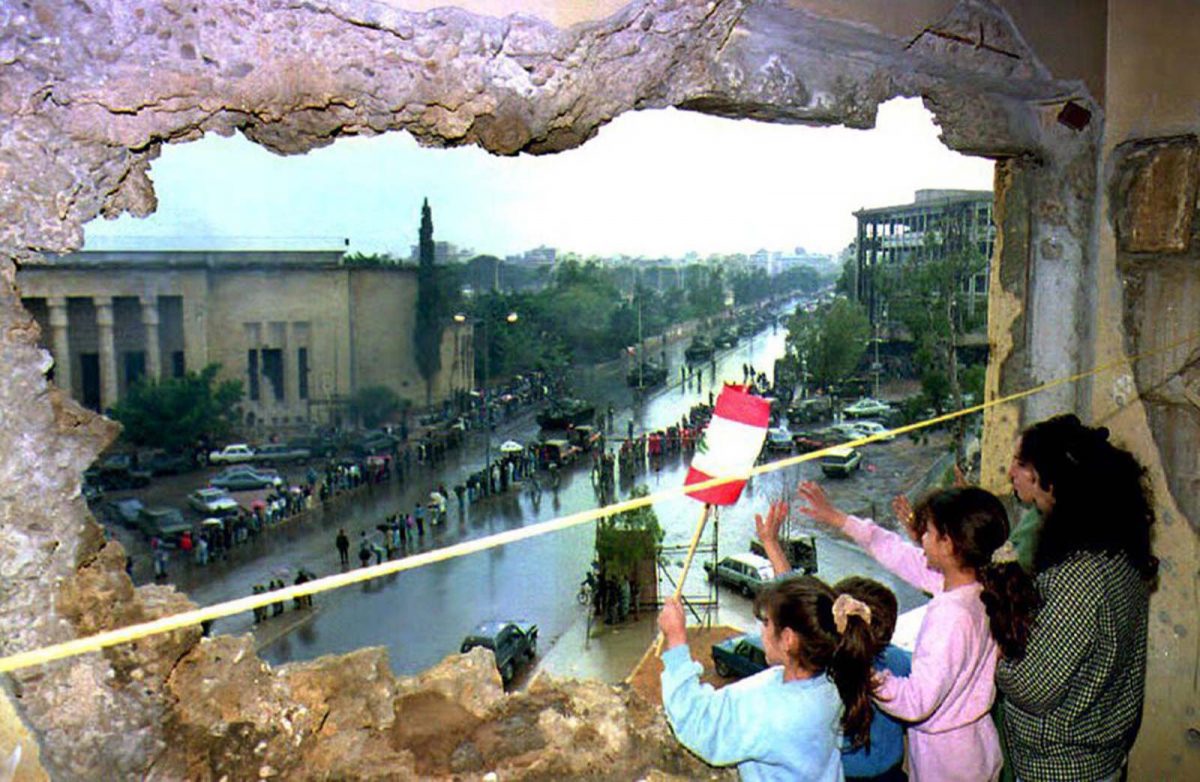

The Green Line in 1990

Beirut Airport 1982

TMA Jet, Beirut International Airport, Beirut, Lebanon, 1982.

Muslim Lebanese Army soldiers set up a Christmas tree on the Green Line to celebrate the holiday with Christian soldiers on December 23, 1987.

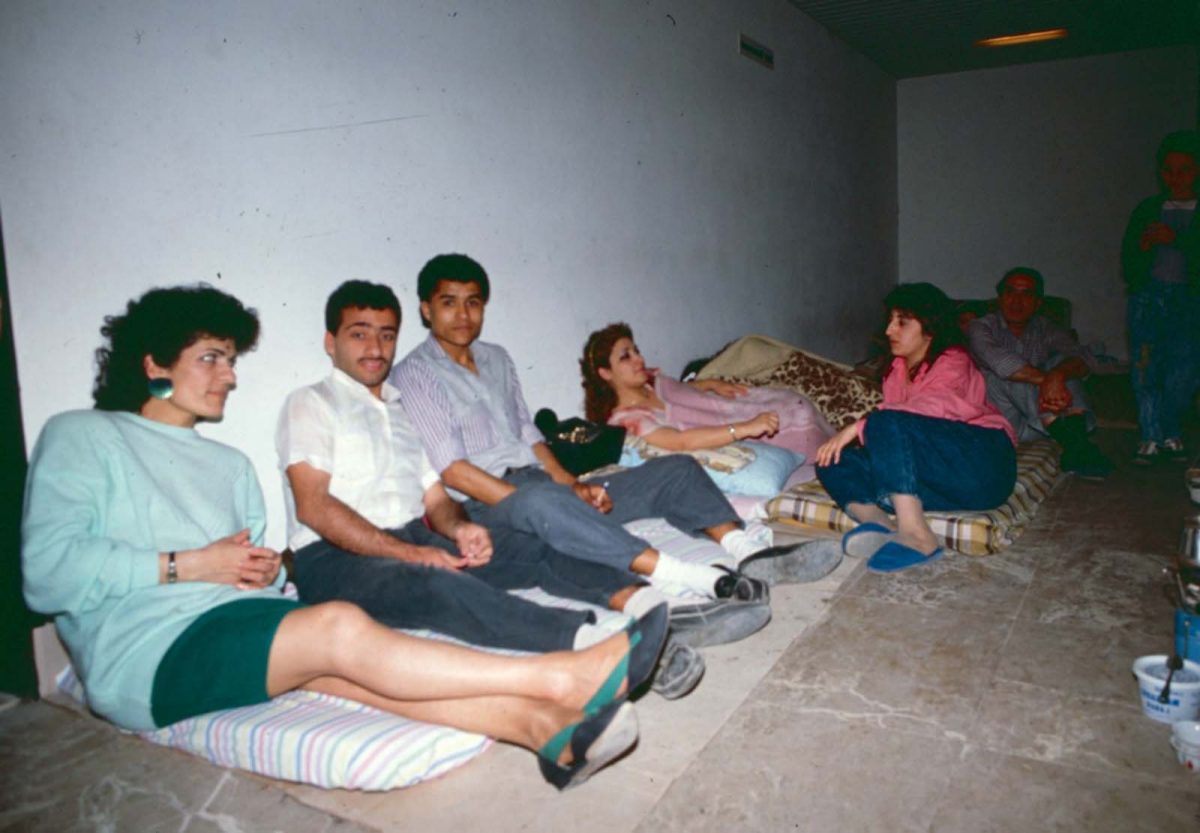

Civilians take shelter in an underground parking garage during heavy fighting in downtown Beirut.

A mother and her children wave to soldiers during a military parade on Beirut’s Green Line for Lebanese Independence Day, November 22, 1992.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.