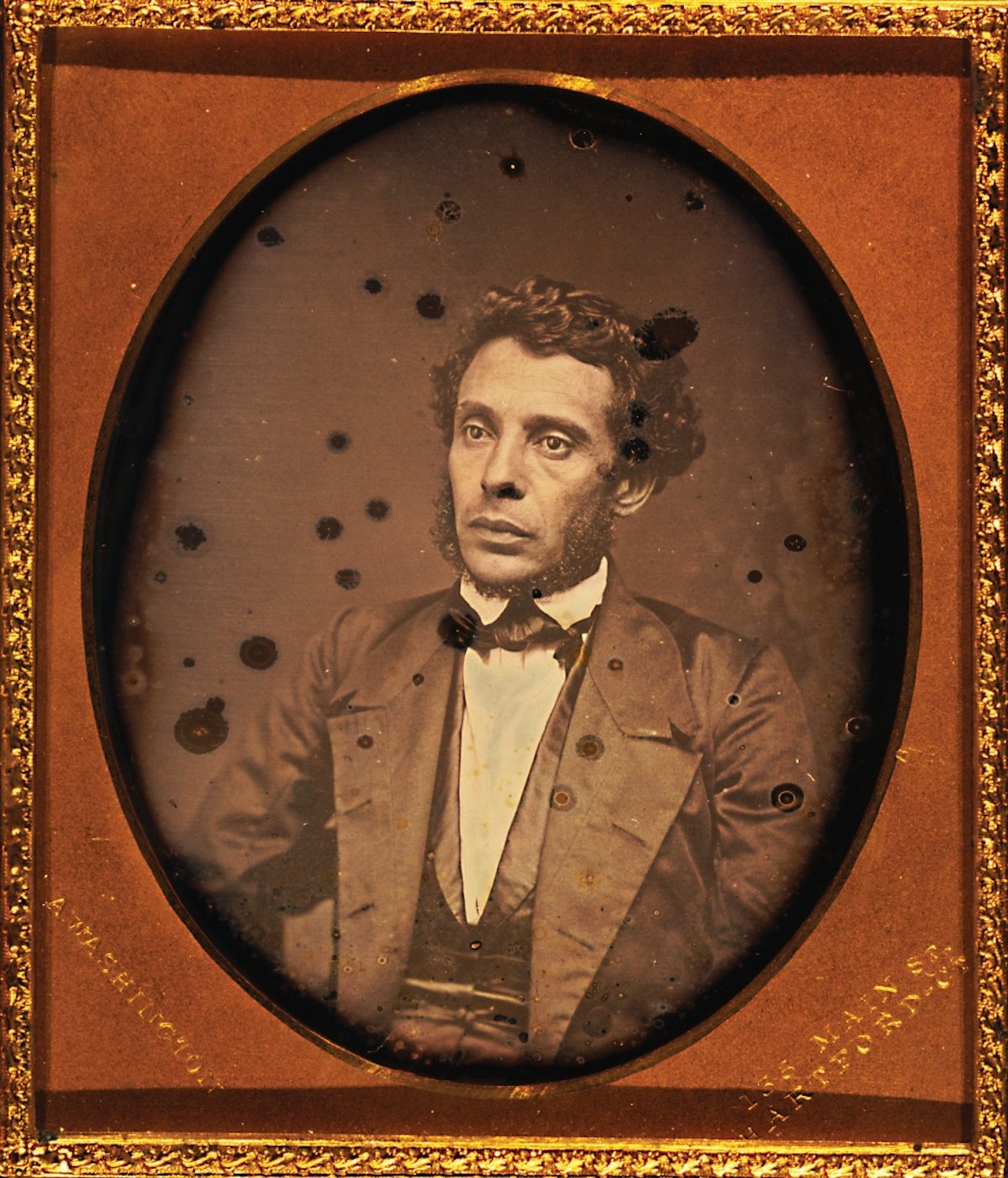

Augustus Washington did not set out to become a successful photographer—or “daguerreotypist” as the occupation was then known. He first picked up the trade to finance his education when his funds ran out after his first year at Dartmouth in 1843. Though he ultimately had to leave college, “within five years,” the Library of Congress notes, he “had a thriving studio in Hartford, Connecticut. By 1850, he was a prosperous photographer.” This was only the beginning of his story.

An African American man active in the Abolitionist Movement, Wilson was born free in Trenton, New Jersey to formerly enslaved parents in 1820. He moved to Hartford in 1844 to help run Talcott Street Congregational Church’s North African School and participate in the church’s anti-slavery work. When he left teaching and opened his own studio in 1846, his was “one of 20 such studios that opened between 1840 and 1855” and one of the few to survive and thrive, writes Mary Muller at Connecticut History.

Portrait of an unidentified woman, by Augustus Washington

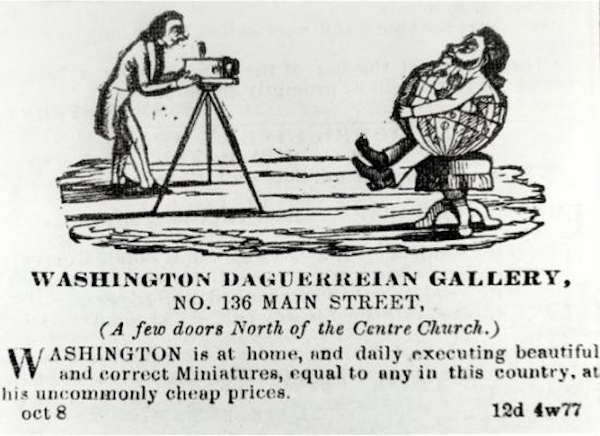

Washington’s skills, and affordable prices, became renowned. “Offering portraits ranging in price from $.50 to $10, Washington attracted a broad clientele, and by the early 1850s was regarded as one of the city’s foremost daguerreotypists.” (The photographic technique had only been invented a few years earlier, in 1839, by Louis Daguerre.) An advertisement (below) shows a photographer taking a picture of the world and reads “Washington is at home, and daily executing beautiful and correct Miniatures, equal to any in this country, at his uncommonly cheap prices.”

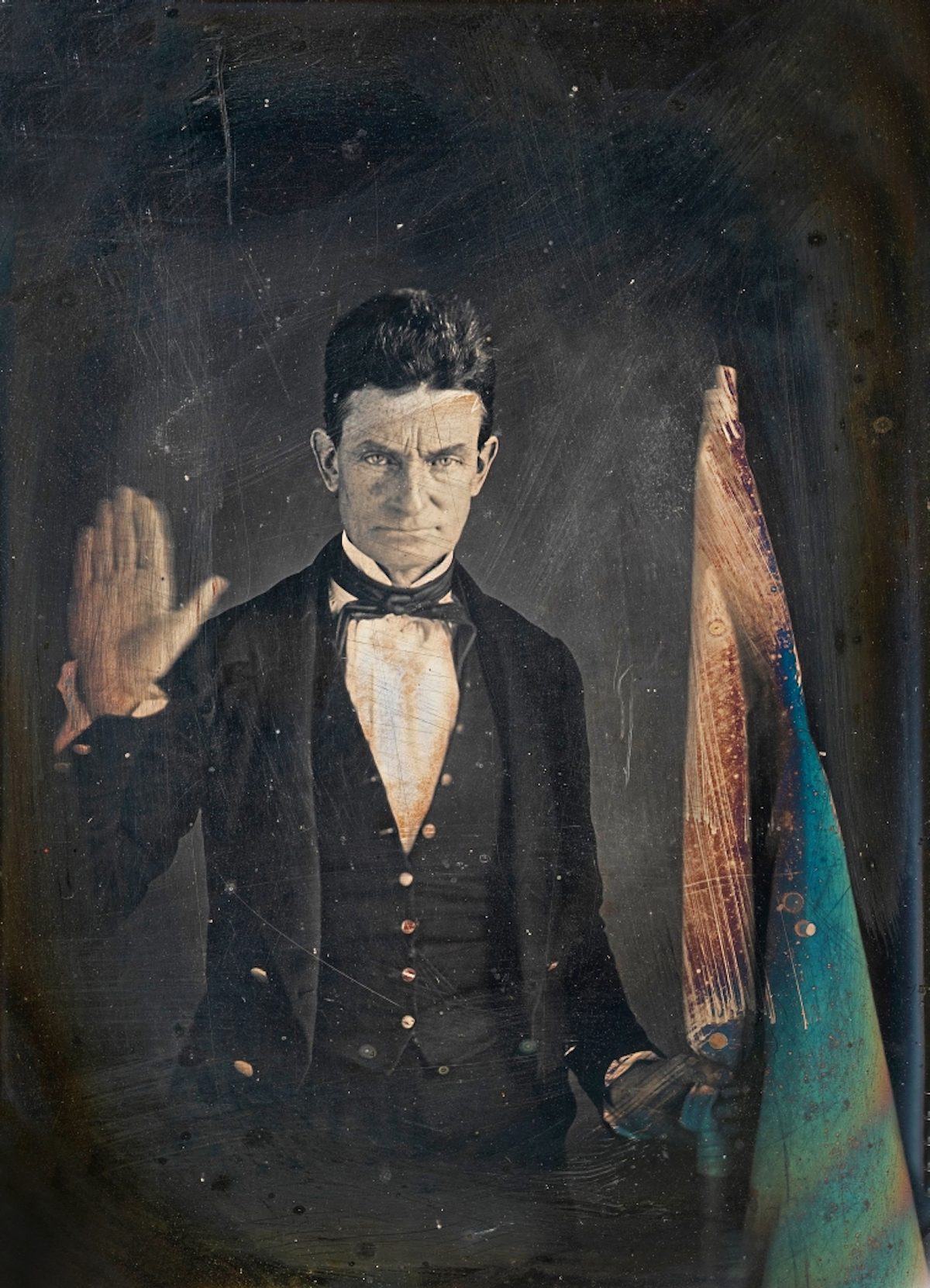

The photographer’s sliding scale made portraiture widely accessible to a variety of people from different classes, and he had a steady stream of clients, from the historic – like John Brown – to ordinary working people in Hartford whose names and histories have been lost to us. (Ironically, none of his portraits of Black Hartford residents have survived, nor do we have a portrait of Washington himself). Washington married and had two children, and he might have settled down and raised his family in contentment, but he was far from content. His activism, anti-slavery work, and his own life experience convinced him that racism would continue to make it impossibly difficult for Black Americans to succeed, even if slavery were overcome.

“Strange as it may appear,” Washington wrote in an 1851 letter to the New York Tribune, “whatever may be a colored man’s natural capacity and literary attainments, I believe that, as soon as he leaves the academic halls to mingle in the only society he can find in the United States, unless he be a minister or lecturer, he must and will retrograde.” Perhaps he felt himself succumbing to this fate when he decided to leave the U.S. for Liberia in 1853. “Disillusioned with America’s treatment of its black citizens,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art writes, Washington moved his family to the West African nation, and “opened the first studio in the capital of Monrovia.”

Through his advertisements placed in local newspapers, we can follow his journey as he visited the main African capitals along the Atlantic coast. In 1860, he arrived in Senegal, where he opened the earliest documented studio in the country. By the 1870s, a number of photographers, such as the Sierra Leonean Francis W. Joaque (ca. 1845–1900) and the Gambian John Parkes Decker, had taken up this activity, working for both European and African clienteles.

Washington photographed many prominent citizens in Liberia, including missionaries, businessmen, the country’s first and seventh president, Joseph Jenkins Roberts, and one of the its first senators, John Hanson, who had purchased his freedom and emigrated from Baltimore at age thirty-six. Washington’s work helped establish photographic portraiture as a thriving business in West Africa. He was also able to realize his larger aspirations, becoming a merchant and sugarcane farmer and serving twice in the Liberian legislature as a representative and once as a senator. When he died in 1875, the American newspaper African Repository published an obituary noting his many accomplishments. The article concluded, “Nothing could induce him to return to this country [the U.S.], having acquired a handsome property and freedom and a home in his ancestral land.”

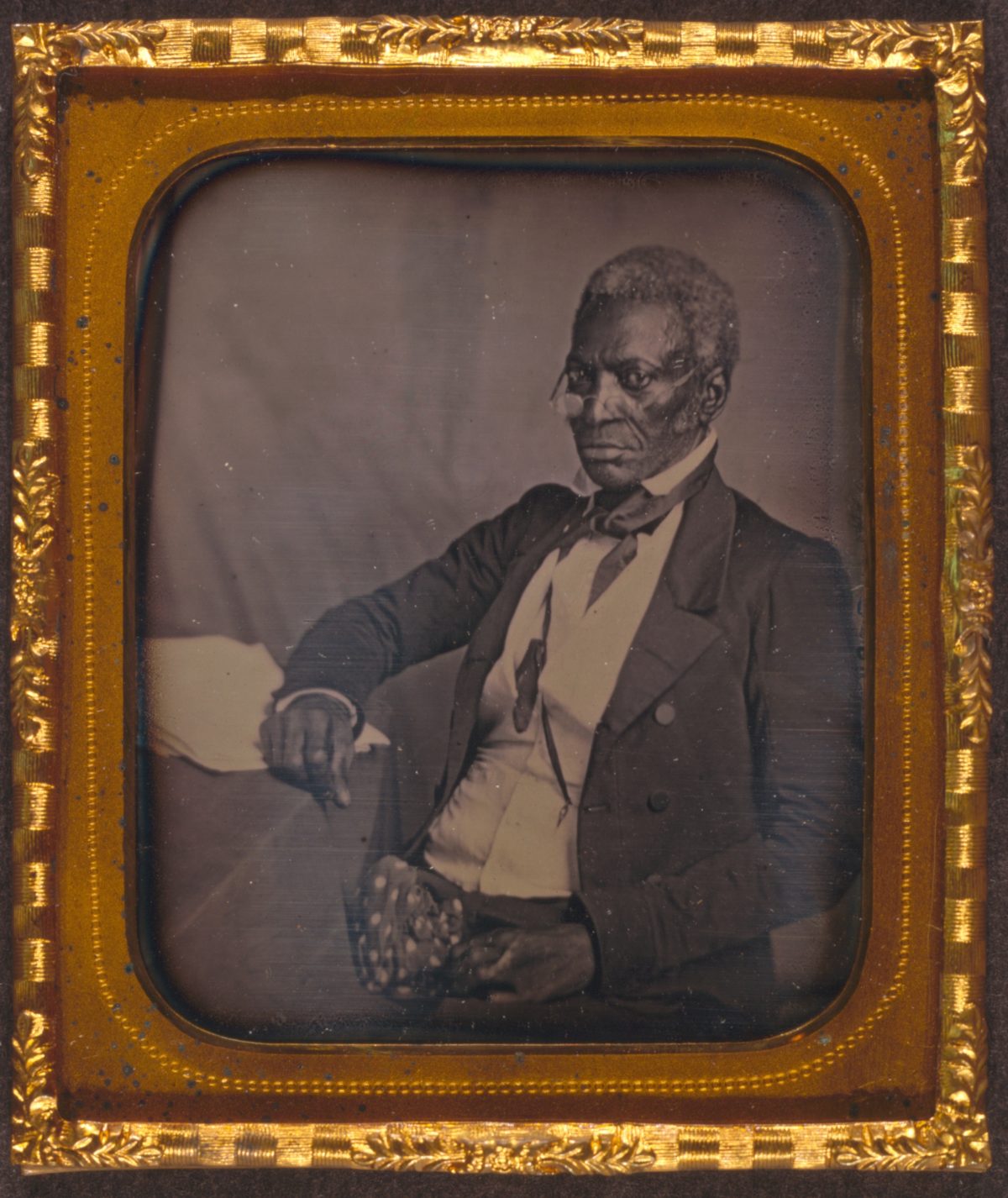

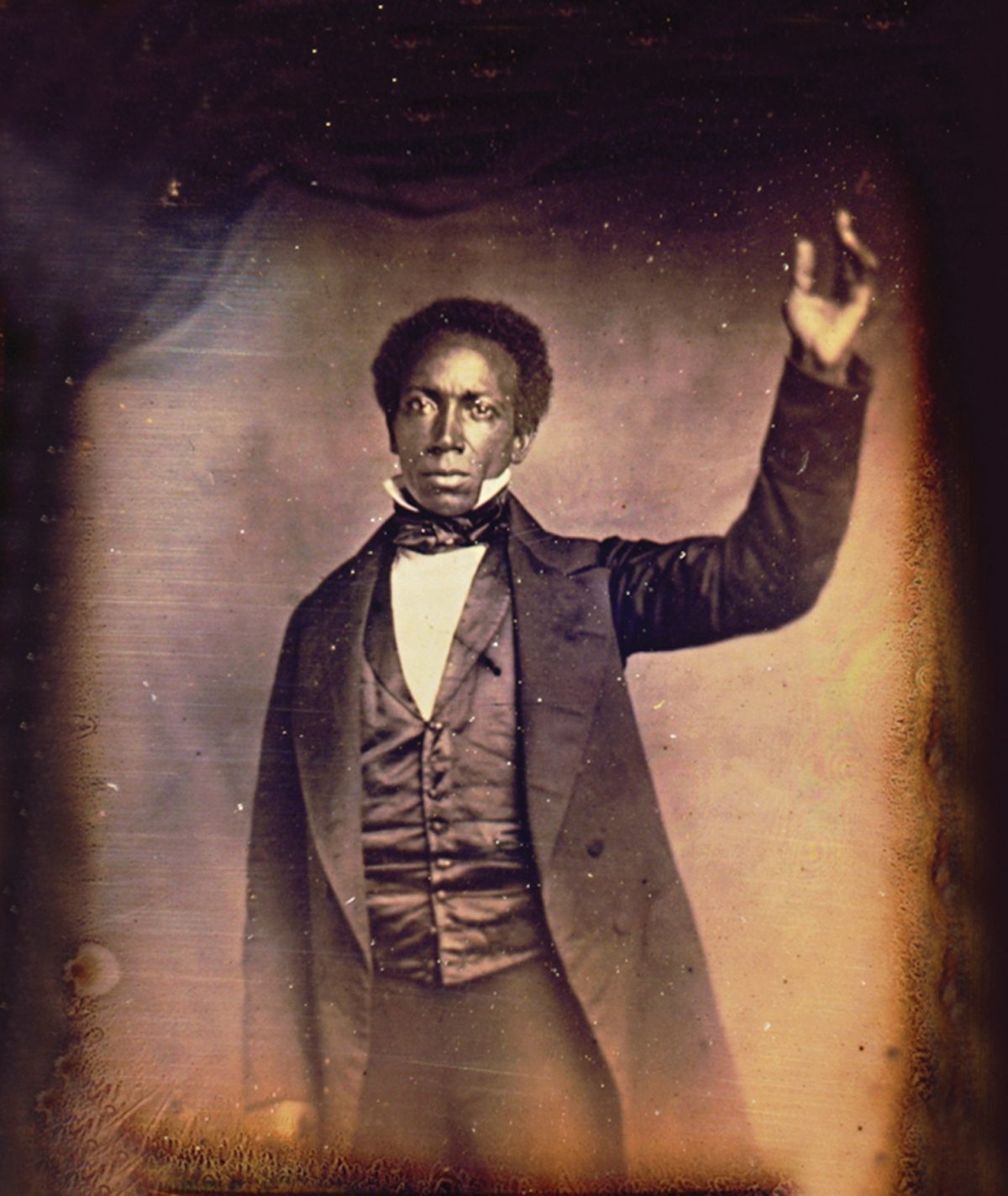

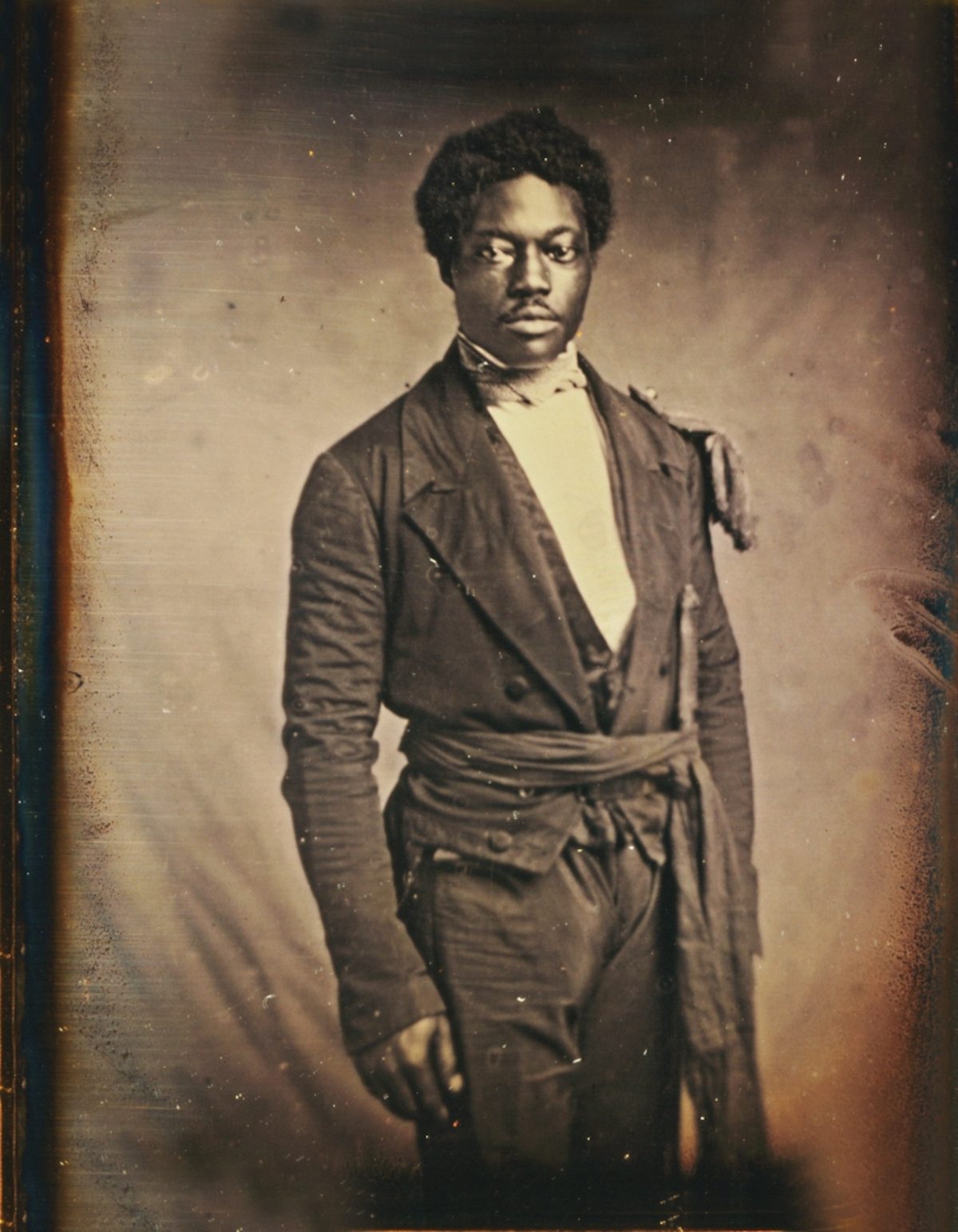

Chancy Brown, Sergeant at Arms of the Liberian Senate, by Augustus Washington

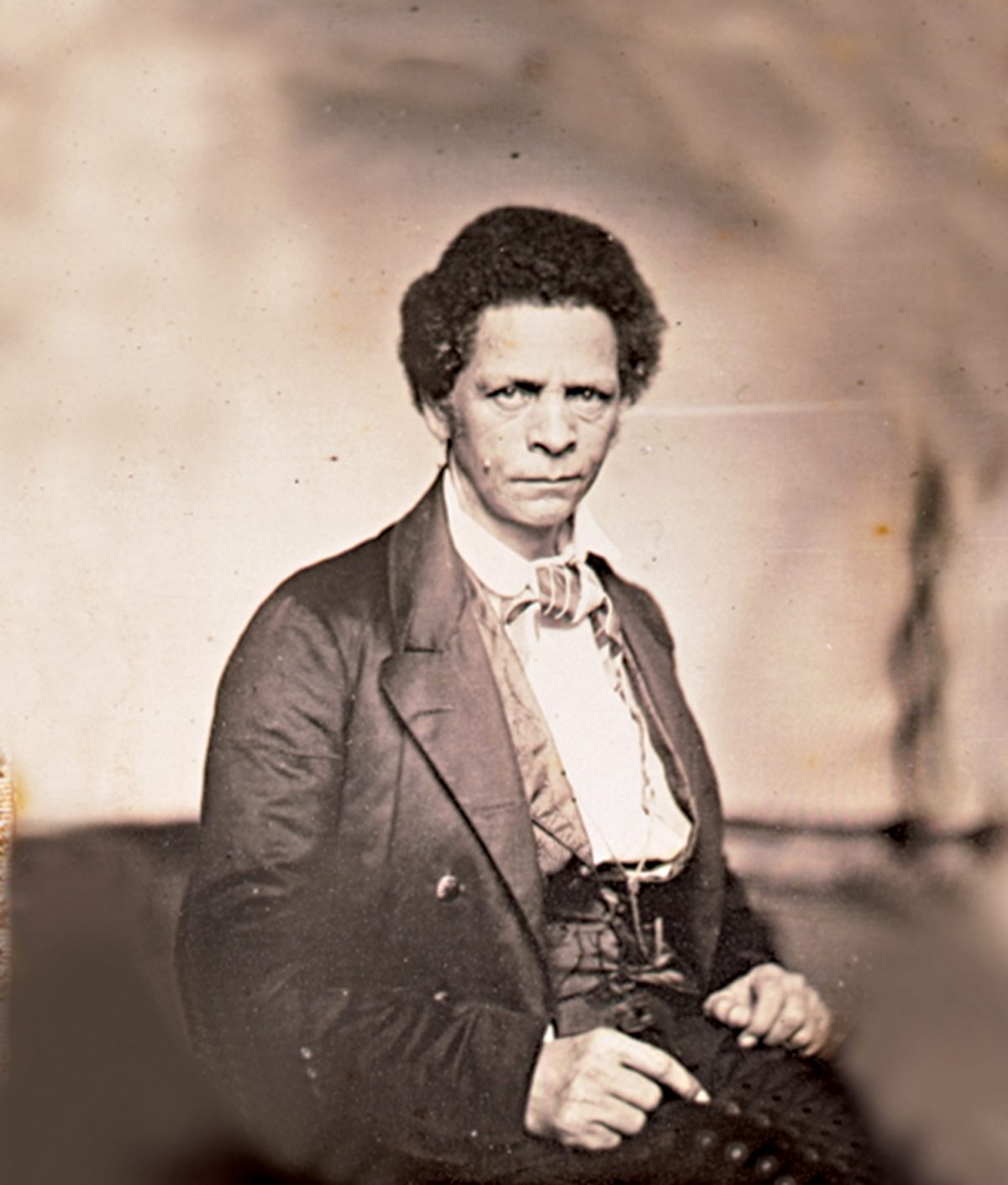

Joseph Jenkins Roberts, the first and seventh president of Liberia, by Augustus Washington

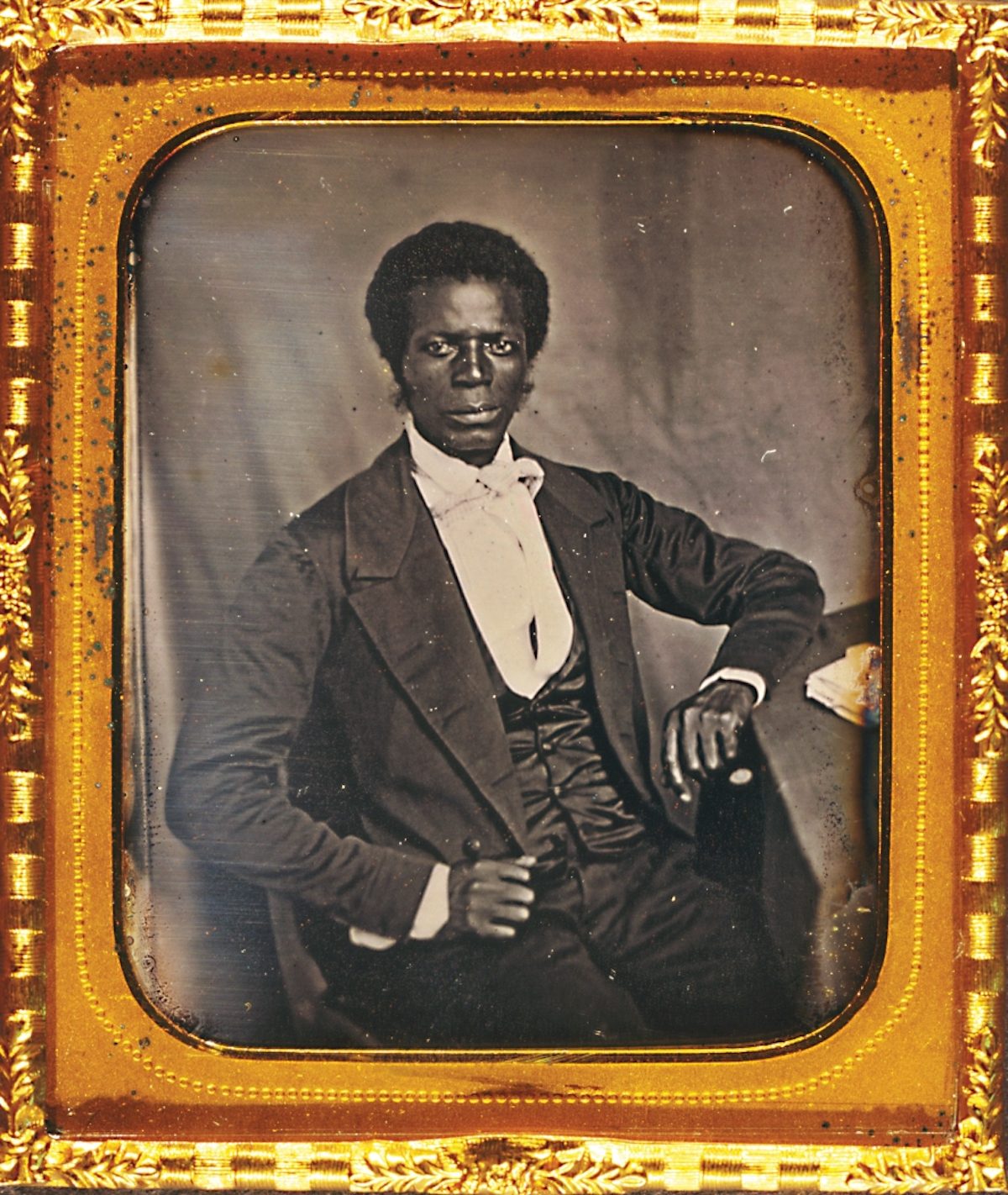

James Mux Priest, the first Presbyterian African American missionary sent to Liberia, by Augustus Washington

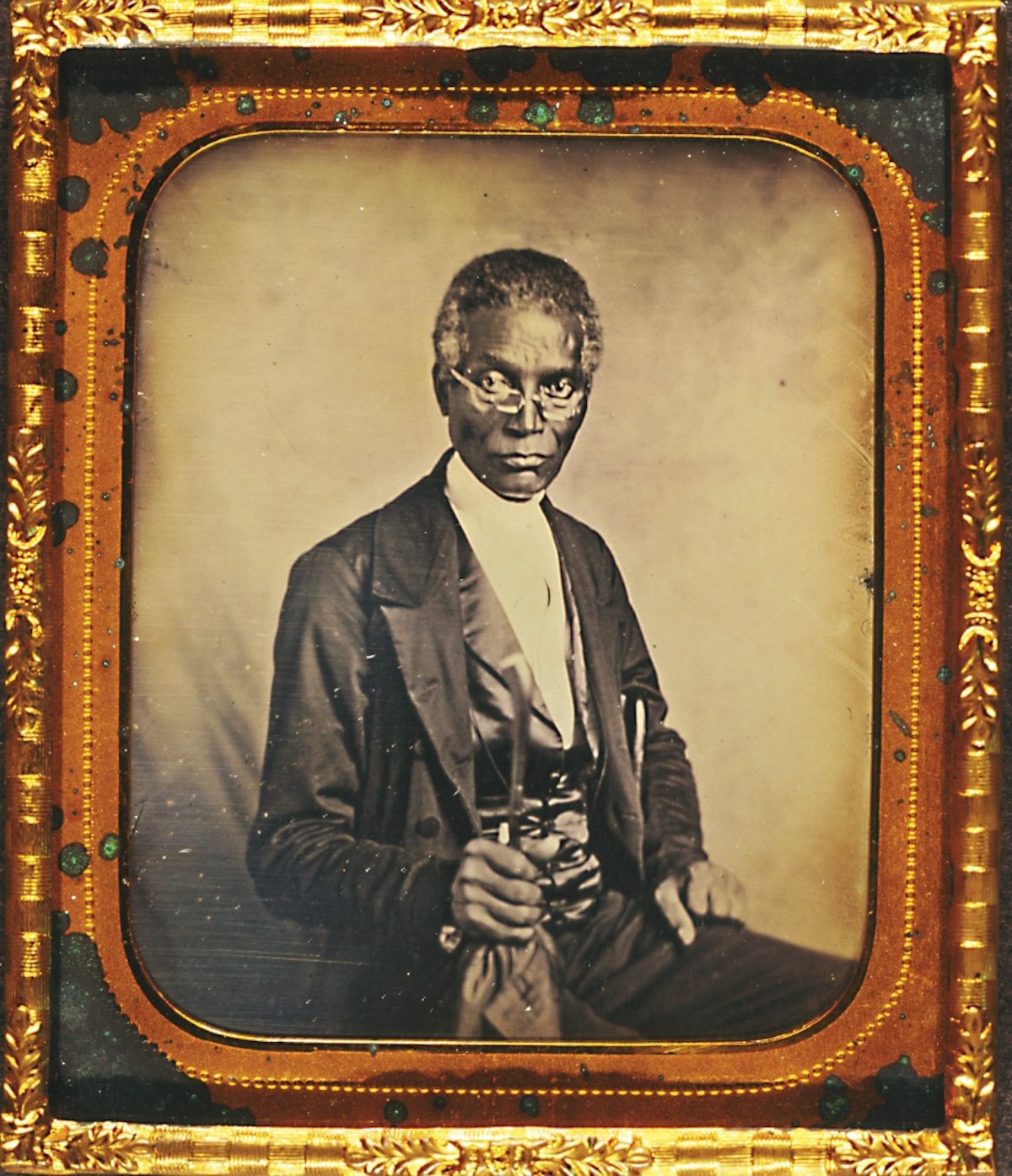

Philip Coker, clergyman and missionary of the Methodist Episcopal Church, by Augustus Washington

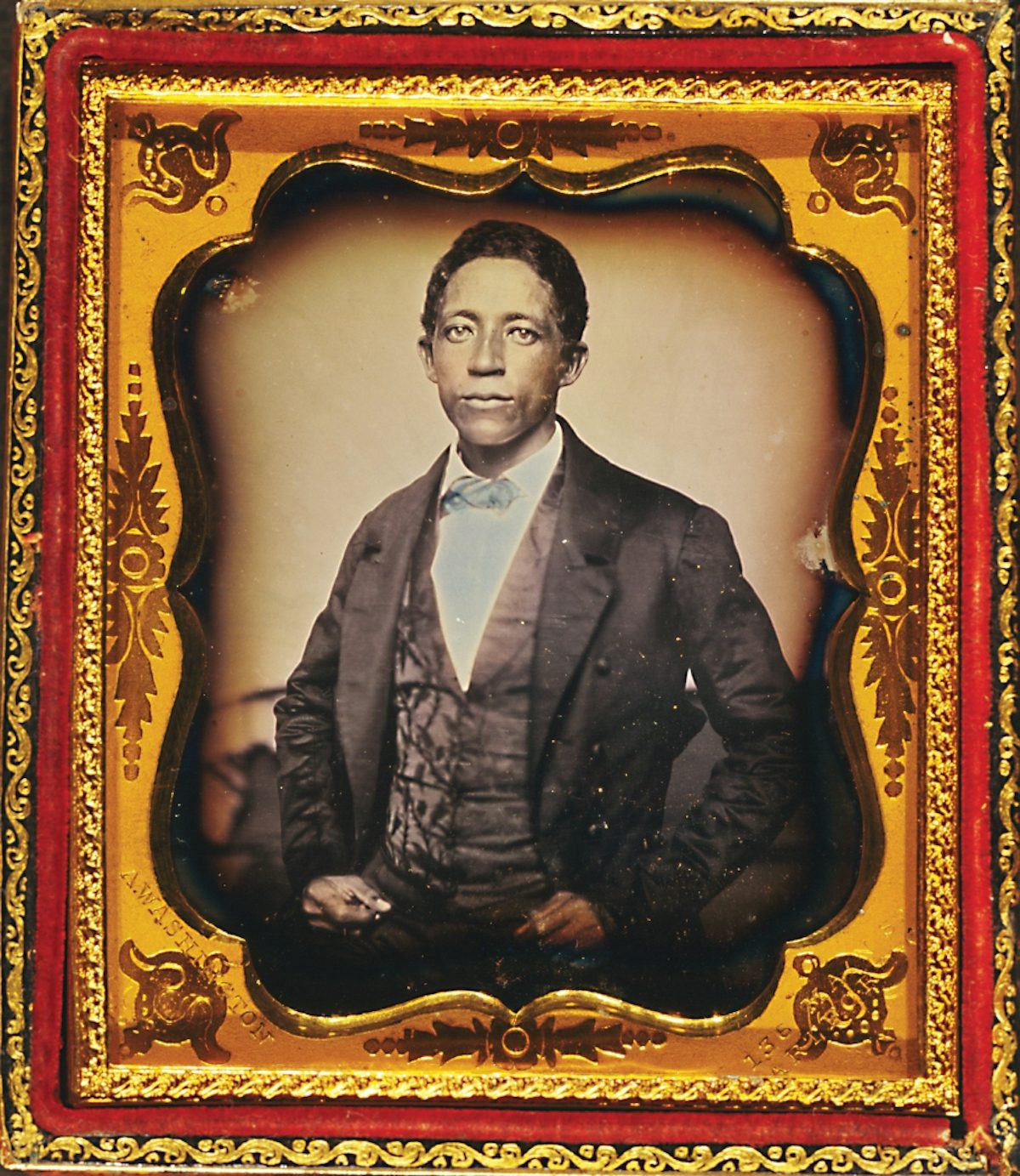

Portrait of an Unidentified Man, by Augustus Washington

Urias Africannus McGill, an American immigrant to Liberia, by Augustus Washington

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.