Washing hands routinely seems like the absolute least one can do to slow the spread of COVID-19 But we take such basic hygienic practices for granted at our peril. A look back at the history of handwashing shows how it only very recently became a widespread recommendation (and a mandate) for preventing the spread of disease. This history also shows the critical role of public health systems in curbing infection, rather than depending solely on the actions of individuals.

Historically, the science of infection moved at what seems in hindsight a maddeningly slow pace, taking hundreds of years between the time germ theories were first proposed in the middle ages to the time they were finally accepted by scientists in the late 19th century. For much of that time, the dominant theory claimed that pollution—“bad air” or “miasmas”—caused disease.

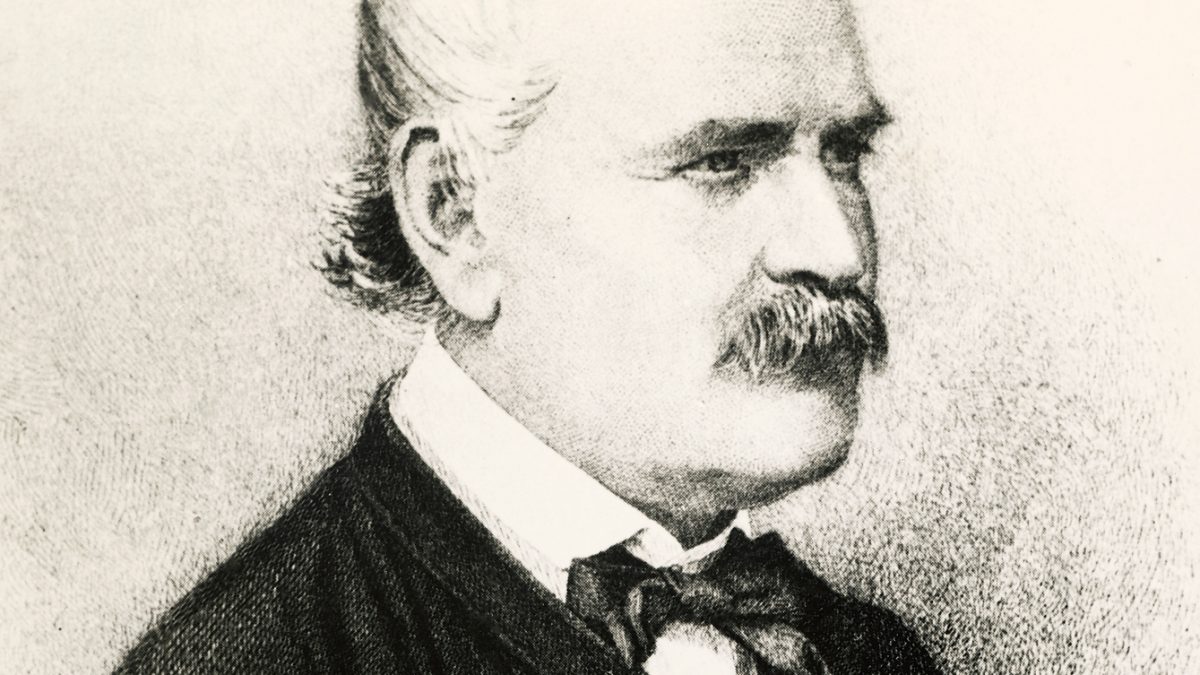

Swimming against the tide, the first advocate of hand-washing, Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis (above) suffered the fate of many a pioneer—he was jeered at, ignored, and, finally, committed to an asylum at age 47, where he died, in a tragic irony, of sepsis in 1865. Before this end, however, Semmelweis, an obstetrician, took a systematic approach to the problem of “childbed fever,” trying to eliminate all of the possible reasons women died at far higher rates when doctors delivered their babies instead of midwives.

In 1848, he hypothesized that doctors, often attending births immediately after conducting autopsies, were transmitting “cadaverous particles” on their hands. Semmelweis had them sterilize their hands and instruments with chlorine, and deaths from childbed fever fell to 1% of cases. But the experiment did not produce a revolution. Semmelweis couldn’t explain his findings, and Miasma theory continued to hold sway, in part, because it did not implicate doctors or others from the higher orders of society in the spread of disease.

Disease, it was thought, was something of a social failing. As historian Nancy Tomes puts it, “the majority of doctors in Vienna at this time were from middle- or upper-class families, and they thought of themselves as very clean people compared with the working-class poor. [Semmelweis] was insulting them when he said their hands could be dirty.” He responded to objections with haranguing letters in which he accused his colleagues of mass murder, calling one “a medical Nero.” Needless to say, this did not help his cause.

Florence Nightingale independently confirmed Semmelweis’ conclusions during her famed service in the Crimean War, and when she returned, she “influenced a new interest in household cleanliness as a goal that a good wife and mother needs to instill in her family.” Even this wasn’t enough to sway the medical establishment, though the work of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch in later decades would finally put an end to the reign of Miasma theory.

“By the 1890s and into the early 1900s,” says Tomes, “handwashing moved from being something doctors did to something everybody had been told to do.” These changes would not take effect universally, however. The history of handwashing involves far more than a change in personal habits over time, but a shift in the understanding of the state’s role in public health. That shift was very slow in coming in places in the U.S., where we see early conditions described in a way that sounds frighteningly familiar to where the country is today.

As historian Michal Sappol writes, “In the 19th century and first three decades of the 20th, the United States was a weak and fragmented nation-state, hobbled by divided sovereignty, laissez-faire ideology, and low tax revenues, unable to cope with the new conditions of industrial modernity and the rise of great cities.” The new science of epidemiology required centralization and collective solutions to implement its recommendations. “Public health encouraged working class individuals to partake in hygiene habits that once symbolized a superior wealthy class,” writes Vanessa Thomas.

The practice of hand-washing was not encouraged by experts in the U.S. so much as by advertisers:

Through soap advertisements the public slowly became aware that germs could be spread through contact with fomites and then transferred by hands. During this period advertisements typically included a doctor’s recommendation that stressed the importance of hygiene, which made the product more appealing for prospective consumers. Mothers were coined as ‘health doctors’ in Lifebuoy’s hand soap campaigns from the 1920s and onwards. Mass advertisement campaigns focused on educating the public to partake in the hygiene practice by promoting hopefulness of good health. Soap companies slowly pushed for the incorporation of contemporary hand washing habits by enforcing the idea of hand washing to prevent the disease transmission. The corporate push to implement hand hygiene was not necessarily for the common good, but rather for the hopes that the advertisements would lead to higher sales.

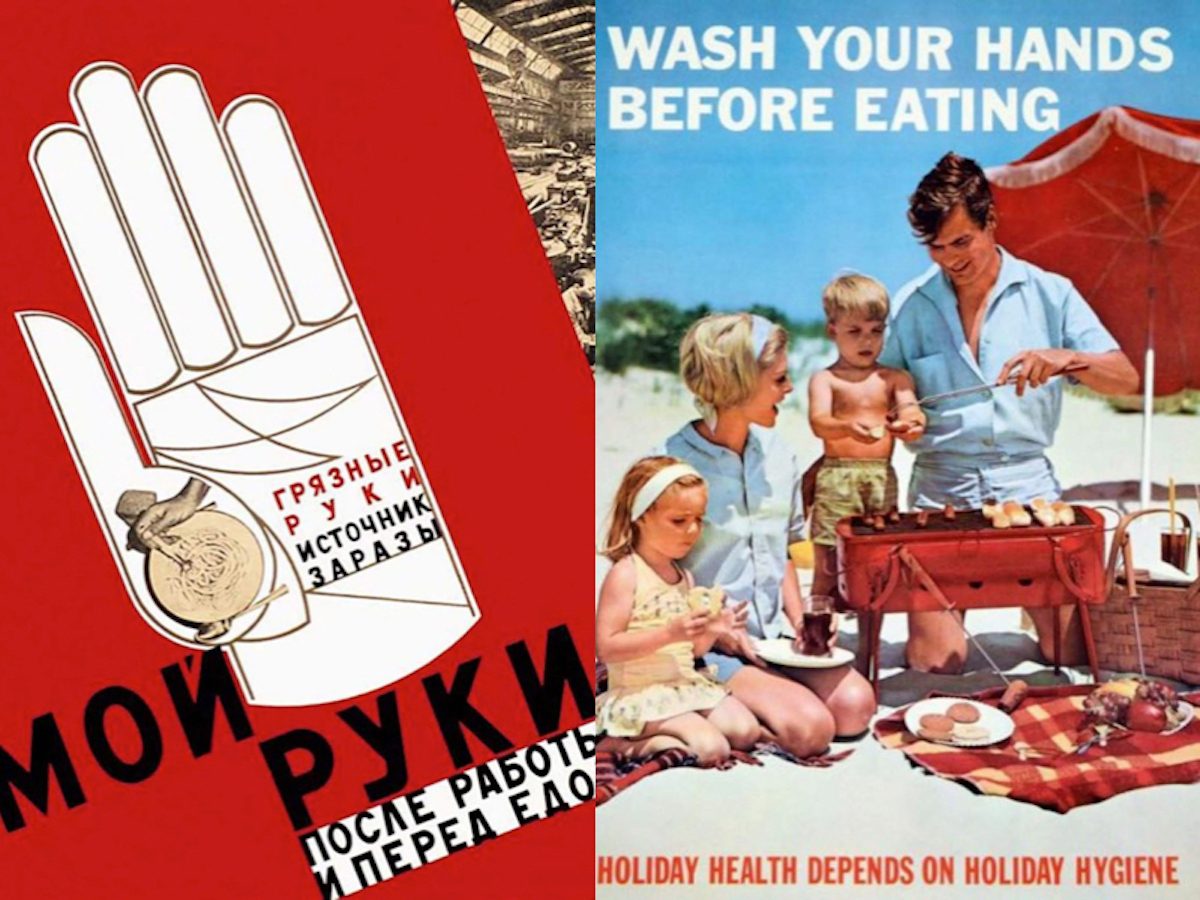

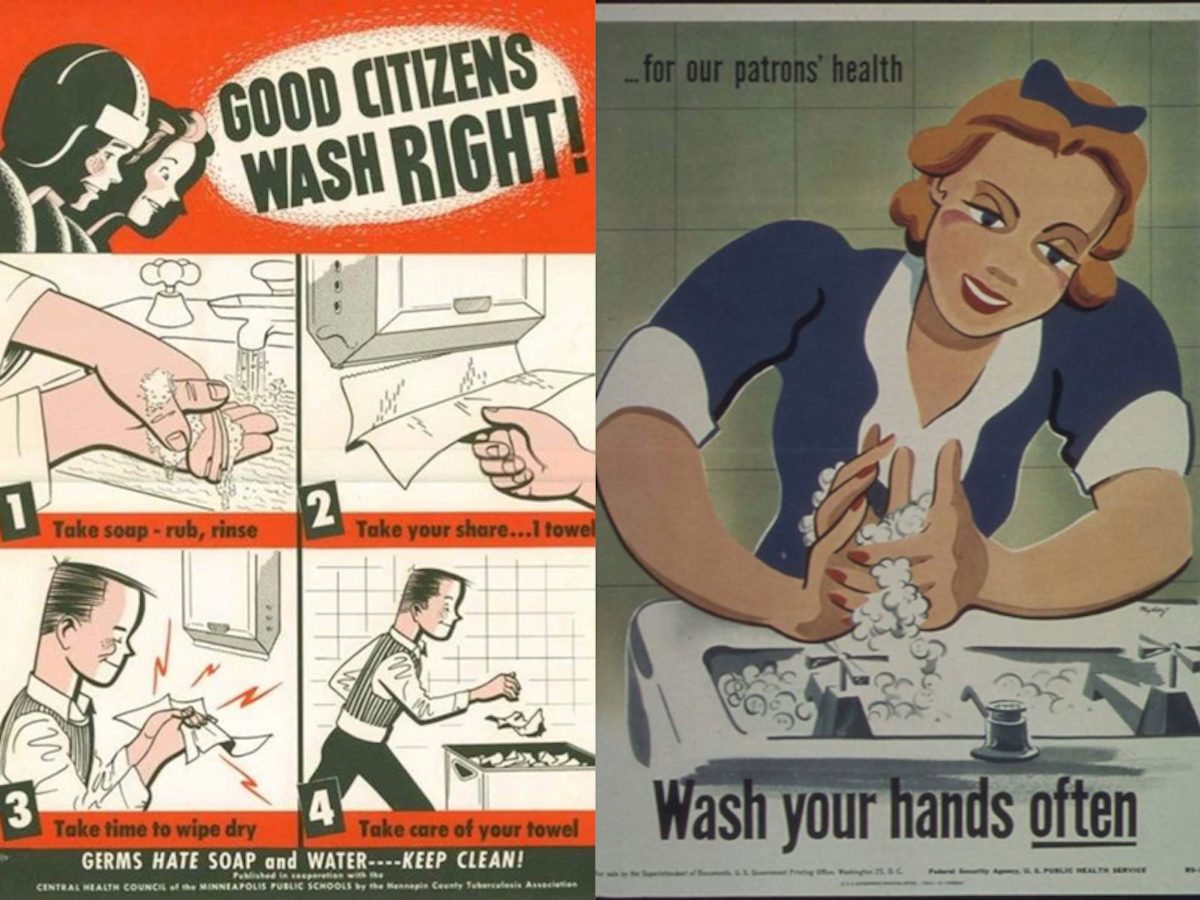

Shifting the burden of controlling disease to the individual, commercial interests sought solely to profit from the new science. The “nanny state” approach undertaken in Britain, or example, would not obtain for some time in the States. Other, more robustly public systems of governance around the world took hand-washing seriously, as some of the vintage 20th century posters here demonstrate, but even after the unhygienic medical practices during WWII led to the founding of the CDC in 1946, the U.S. would not adopt hand-washing as an official federal public health practice until 1981—almost 100 years after Koch’s postulates—when the state finally stepped in to prevent deaths due to unsanitary conditions in public facilities everywhere.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.