Up this green woodland-ride let’s softly rove,

And list the nightingale—she swells just here.

Hush! Let the wood-gate softly clap for fear

The noise might drive her from her home of love—John Clare, “The Nightingale’s Nest”

The idyllic English countryside of the poet and farm laborer John Clare can seem as far away from our digital age as that of Chaucer. But the idylls Clare described in 200 years ago had already been under threat for several decades by the enclosure of common pasture and hunting grounds, industrialization, and the mass exodus from the villages to the cities and towns, a phenomenon Clare bitterly lamented. As far back as 1770, another poet, Oliver Goldsmith, wrote about the death of country life in his moving elegy “The Deserted Village,” in which he wept over the idealized “Sweet Auburn! parent of the blissful hour, / Thy glades forlorn confess the tyrant’s power.”

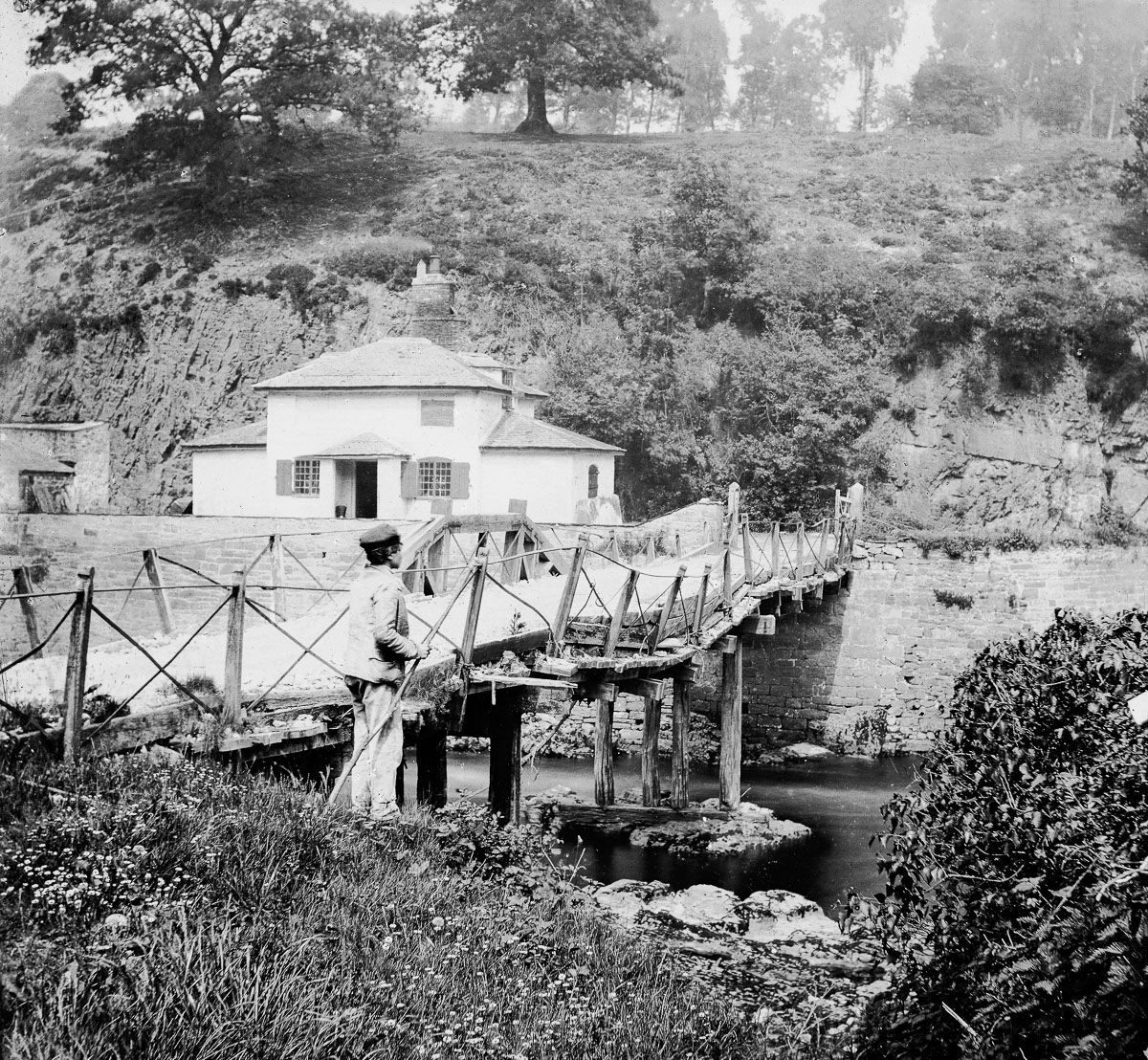

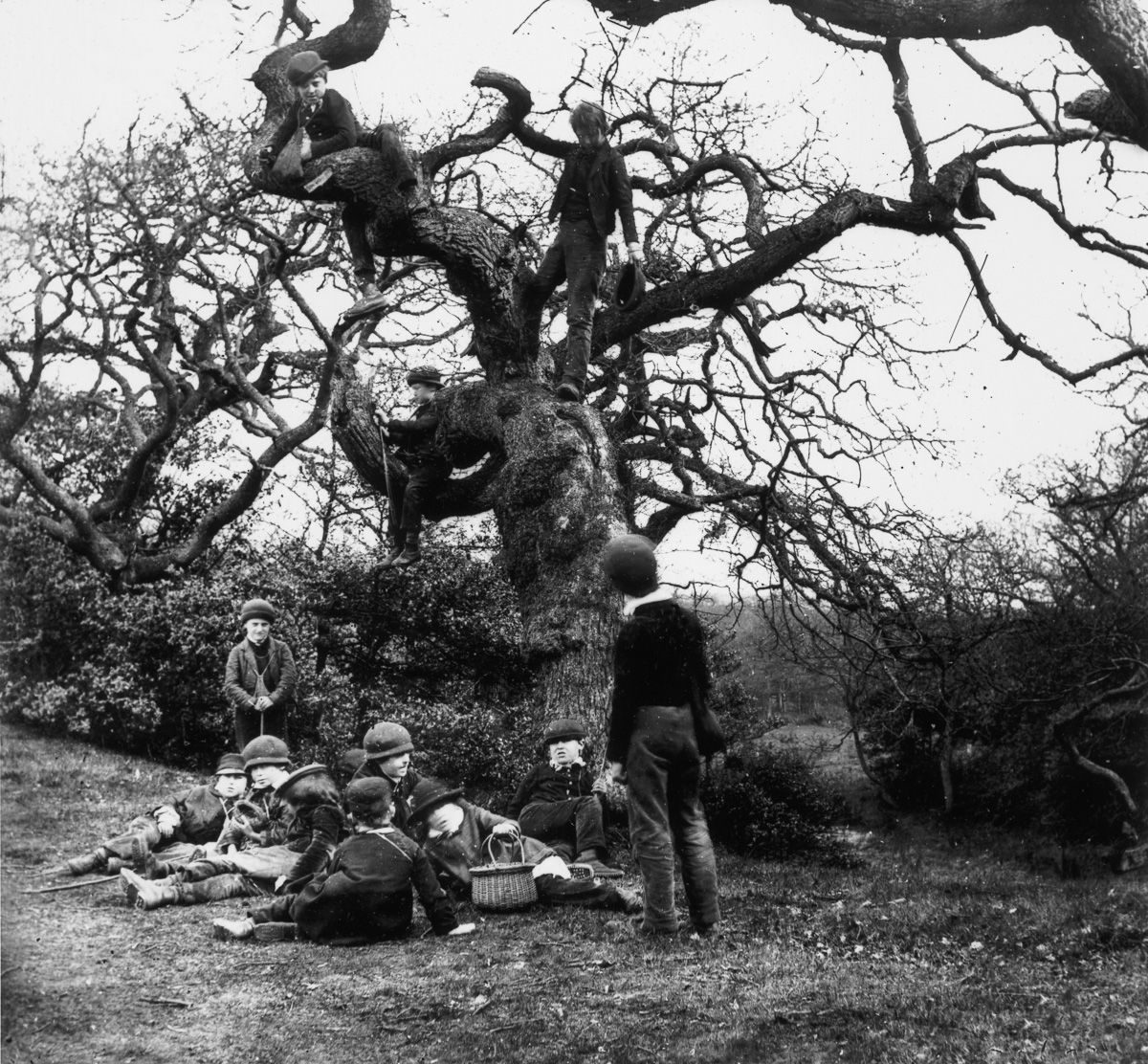

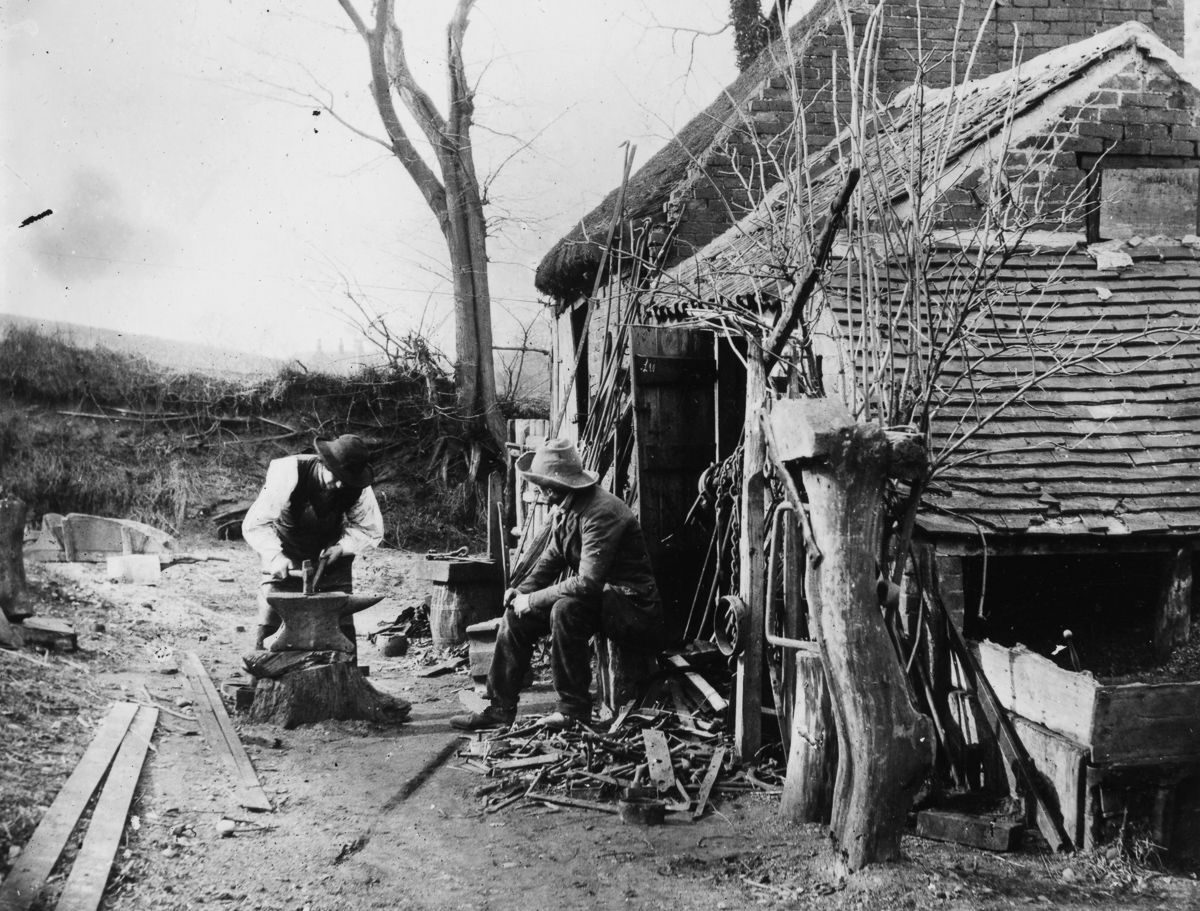

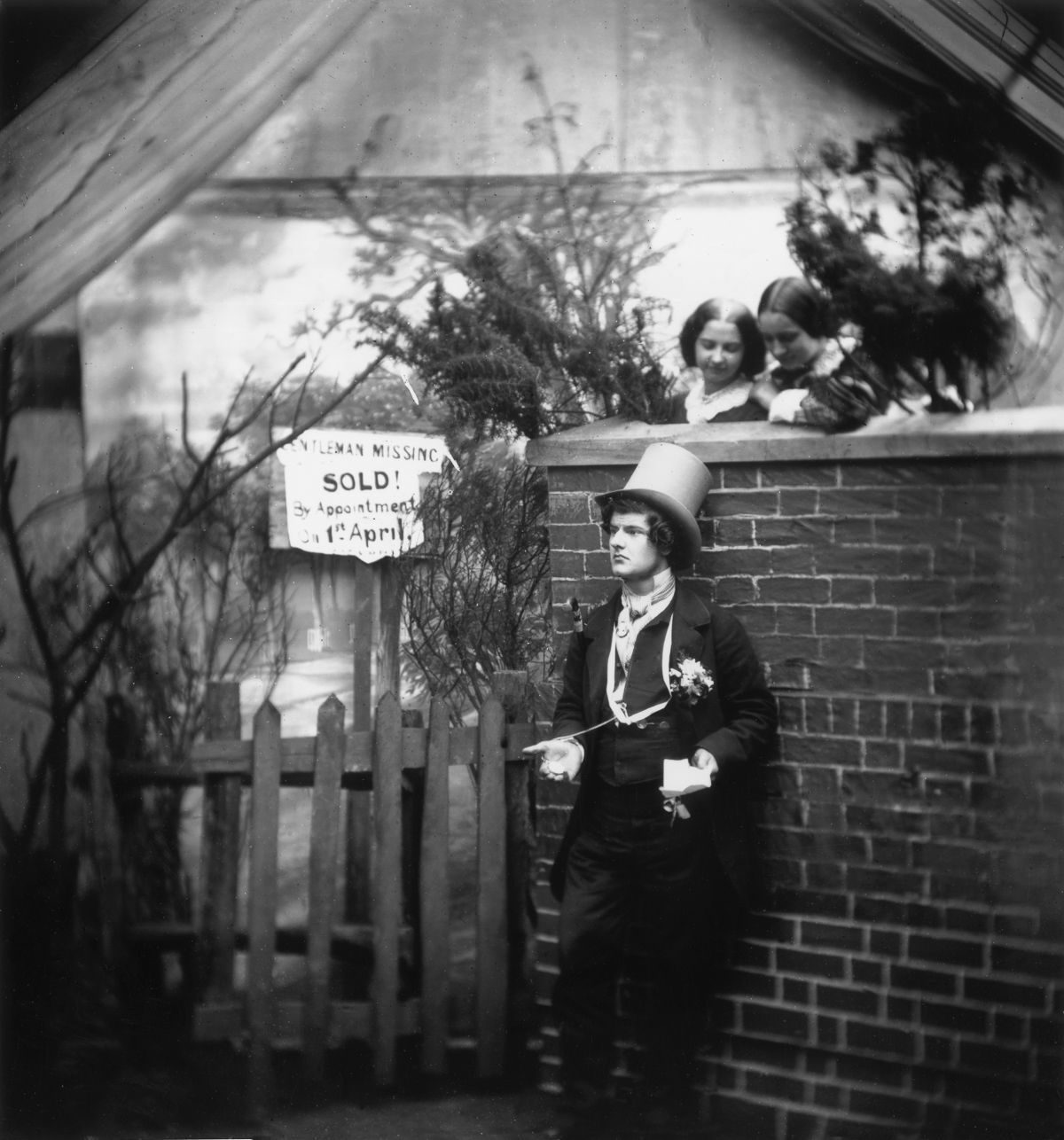

By the early Victorian period, English country life seemed like an anachronism amidst proliferating railroads, steamships, and advancing consumer culture. In the mid-1850s, as Clare spent his last years in an asylum, believing himself a prizefighter, Lord Byron, and other delusions, the photographer William Morris Grundy took up a camera and began making ersatz portraits of the disappearing country life the poet loved. Grundy made “dozens of stereoscopic photos,” writes Alex Q. Arbuckle, “primarily posed genre scenes of rustic pursuits such as hunting, fishing, and farming.” After his death in 1959, the photos were “used as illustrations for a book, Sunshine in the Country: A Book of Rural Poetry.

The book was a “harbinger,” writes Victorian scholar Helen Groh, “of what Weston Naef has called the ‘golden age of photographic book illustration.’” With poetry by Wordsworth, Longfellow, Alexander Pope, William Cowper, Thomas Gray, and Clare, among many others, it also represented a prime example of literary nostalgia for a simpler time—a longing for a pastoral past in a Dickensian age of exploitation and loss. The general tenor of the collection, and Grundy’s photos, can be summed up by the title of its first poem, John Gay’s “Rural Pleasures.” Tellingly, Sunshine in the Country did not collect Goldsmith’s “Deserted Village,” nor the poems in which, as George Monbiot writes, Clare documented “both the destruction of place and people and the gradual collapse of his own state of mind”:

Inclosure came and trampled on the grave

Of labour’s rights and left the poor a slave…

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

All sighed when lawless law’s enclosure came.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.