Even in space, the ultimate enemy is…the court system. Throughout science fiction TV history, the greatest heroes of all time have faced this litigious menace, standing trial and running up against a judicial system bent on destroying them.

To put it another way, the success of Perry Mason (1957 – 1966) has had an undeniable ripple effect on space adventure TV, as odd as that seems.

Even in the final frontier, there are judges, juries, witnesses, and attorneys. Even in the distant reaches of space and time, viewers are fated, it seems, to hear such exclamations as “objection, your honor!” or warning phrases like “this is highly irregular….but I’ll allow it.”

Gazing across the space TV canon, one can see how every space hero worth his or her salt has been wrongly accused of a crime, and cast into alien and draconian brands of justice and punishment.

Seeing so many episodes featuring space age heroes standing trial, decade-after-decade, franchise after franchise, one sees that these entertainments are pondering the shape and breadth of justice in a new setting; one of technological breakthroughs and new morality.

Below are at least ten occasions in sci-fi TV history in which heroes went before a jury of peers to stand judgment for their “crimes.”

Star Trek (1966 – 1969)

In the first season episode titled “Court Martial” Captain Kirk (William Shatner) is tried by Starfleet Command. The charge is criminal negligence in the death of a crewman named Ben Finney (Richard Webb). The ensuing trial is prosecuted by Kirk’s old girlfriend, Areel Shaw (Joan Marshall), though she probably have recused herself, given the nature of the prior relationship with the defendant.

During the course of the trial, Shaw presents incontrovertible computer evidence against the good captain. Kirk choked at a crucial moment, according to the computer testimony, and ejected Finney’s pod before a true emergency existed, thus killing Finney. The cost of this error: Kirk’s command.

But the beleaguered Captain Kirk retains a book-loving 23rd century defense attorney named Cogley (Elisha Cook) — think of a “cog” in a wheel — who makes the case about Kirk’s primary accuser, an inhuman, unfeeling computer. He puts a stop to the steam-roller of injustice by throwing himself into the proceedings.

“The Bible, The Code of Hammurabi, and of Justinian, Magna Carta, The Constitution of the United States, Fundamental Declarations of the Martian Colonies, The Statutes of Alpha III. Gentlemen, these documents all speak of rights,” Cogley asserts. “Rights of the accused to a trial by his peers, to be represented by counsel, the right of cross-examination. But most importantly, the right to be confronted by the witnesses against him; a right to which my client has been denied.”

What “Court Martial” concerns, actually, is “humanity fading in the shadow of the machine,” the notion that technology can take away our liberty and freedom.

The original Star Trek returned to the milieu of the legal trial for the two-parter “The Menagerie,” which saw Mr. Spock threatened with the last death penalty still on Starfleet books. There was another trial too, in “Turnabout Intruder,” during which Spock was tried for mutiny when a usurper, Janet Lester, appropriated Kirk’s body. Even Scotty (James Doohan) himself was accused of murder, and required defense, in the second season episode of the series, “Wolf in the Fold.”

The Starlost (1973 – 1974)

In the episode “Children of Methuselah,” protagonists Devon (Ker Dullea), Rachel (Gay Rowan) and Garth (Robin Ward) discover a chamber they presume to be the Earthship Ark’s back-up bridge. The bridge, however, is guarded by a group of apparently immortal children.

Hundreds of years earlier, these children were deliberately injected with a serum that instantly regenerates their cells. They also possess a serum to restore “natural aging” once the ship’s crew returns. Meanwhile the children, led by Captain One (David Tyrell) have been training on the bridge’s controls for hundreds of years.

When Devon insists that the Earth Ship Ark is on a collision course with a star, Captain One is able to demonstrate, via the bridge’s equipment, that he is wrong. Because Devon has passed false information, to bridge officers, Captain One tries him for lying in court, and orders both Devon and Garth executed, while Rachel is made a “ward of the dome.”

Now Devon must defend himself in court, and prove two things. First, he must prove he is not a liar, and secondly that everyone on the Ark is doomed unless he can change the ship’s course. His “defense” is an example of the notion that the court room can be a crucible not just for truth, but for valuable social change. If he wins, society also wins.

Alas, the court of Captain One in “Children of Methuselah” is the very definition of a kangaroo court. There is no real opportunity for Devon to win.

Battlestar Galactica (1978 – 1979)

Glen Larson’s Battlestar Galactica (1978 – 1979) postulated alien “brothers of Man” from a distant galaxy. These humans hailed from a system of Twelve Colonies, and considered Earth to be the lost Thirteenth Colony. In other words, as expressed by the series, the Colonials and the Terrans share a common, root culture.

This conceit or leitmotif is played throughout the series with names of people, places and technology that suggest a shared mythology or history. Characters are named Adama (“First Man”), Apollo (after the Greek God), etc. Villains are named Lucifer, Iblis, and Baltar (after Baal).

In “Murder on the Rising Star,” which first aired on ABC on February 18, 1979, the Colonial legal system is displayed for the first and only time on the space opera series. Lt. Starbuck (Dirk Benedict) is accused of murdering Wing Sergeant Ortega (Frank Ashmore) after a game of triad, and prosecuted by the most experienced “Opposer” in the fleet, Solon (Brock Peters). Apollo (Richard Hatch) and Boomer (Herb Jefferson Jr.) act as Starbuck’s defense team (“Defenders”) while Commander Adama (Lorne Greene) acts as the judge in the case.

What’s most interesting in this “mystery” is, again, how that conceit of connecting Earth mythology to our “Brothers” in space is applied. For instance, Solon is a famous name from Greek history. The archon Solon, who lived circa 600 BC was known as one of the Seven Wise Men of Ancient Greece, remembered for ending enslavement as a means of paying debt, and for splitting the Athenian population into four classes based on wealth. Importantly, Solon was also a lawmaker presiding over Athens in a time of perceived moral bankruptcy or decline.

In “Murder on the Rising Star,” this Solon has undertaken the task of punishing the guilty, those who have transgressed against the moral code of the Colonies. Unfortunately, he targets the wrong man. The idea here is of Solon as perhaps too zealous a crusader against moral bankruptcy. The solution to the mystery in “Murder of the Rising Star” involves landing Starback between two criminals: Baltar and a man named Charybdis, another name from Greek myth. In myth, Charybdis was a treacherous whirlpool which devoured any and all unsuspecting sea vessels that happened by. In this case, Charybdis is just as destructive a personal force: a man who hatches a scheme for murder and nearly takes down the innocent Starbuck with him.

Blake’s 7 (1979 – 1981)

In the inaugural episode of Blake’s 7, “The Way Back,” a former resistance leader of the Freedom Party, Roj Blake (Gareth Thomas) lives in a high-tech totalitarian state. When he awakens from an induced form of amnesia and attempts to carry on his work as a dissident, the State promptly captures him and holds him for trial…as a child molester. At his trial by the Justice Department, Blake is sentenced to life on a distant penal planet, Cygnus Alpha.

Blake’s trial is a blatant attempt to destroy him in the eyes not of the State, but of the people. He is (falsely) charged with the worst crime possible, sexual abuse of minors, and so his very name is ruined in the public eye. This charge of child molestation is designed so that citizens will associate dissidence or civil disobedience with a convicted pedophile. No one will want to join the Freedom Party in lights of its former leader’s behavior.

Again, the idea of a kangaroo court is in play. The outcome of Blake’s trial is pre-ordained. The whole “show” has been arranged to discredit him and his life’s work, and to get him out of the way.

Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979 – 1981)

An episode of the second season of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979-1981) reveals that due process, and specifically the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution don’t survive beyond the Holocaust in the year 1987.

The Fifth Amendment declares, in part, that no person “shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself,” and that’s the portion I shall refer to here. In “Testimony of a Traitor,” a twentieth century videotape found in the ruins of Anarchia incriminates Buck Rogers (Gil Gerard), suggesting that he was actually part of a cabal of nuclear hawks in the 1980s and therefore played a critical and specific role in starting World War III.

Aboard the Searcher, no one believes that Buck could be responsible for genocide, but the videotape seems convincing. To clear his name, Buck uses Dr. Goodfellow’s (Wilfrid Hyde-White) “memory probes” to determine what happened to him, and his own memories are used as evidence against him on trial — actually played on the screen as if a live video feed. This is a clear violation of the principle of the Fifth Amendment. Rogers’ memories are used against him in a legal proceeding.

In the end, Buck’s memories reveal that he was actually a double-agent, infiltrating the cabal at the behest of the U.S. president, and all charges against Buck are subsequently dropped. But still, he bears witness against himself, appearing guilty, until the trial “reaches” the memories that prove exculpatory

Doctor Who (1963 – 1989)

In the mid-1980s, Colin Baker’s Sixth Incarnation of the Doctor is tried by the Gallifreyans — his own Time Lord people — in the season-long Dr. Who serial “The Trial of a Time Lord

There, the Doctor is prosecuted by a twisted future incarnation of himself, “The Valeyard” (Michael Jayston).

It turns out, the Doctor is actually being framed for a crime committed by his people, and his old enemy the Master, proves to have some knowledge of that in a later episode.

Interestingly, and in keeping with his Time Lord nature, the Doctor presents as exculpatory evidence an adventure from the future; one that has not yet occurred (“Terror of the Vervoids.”)

The season long “Trial of a Time Lord” involves corrupt authority, and the desire of an institution to hide its own dark secrets by silencing the one person who could be a whistle blower about its activities.

Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987 – 1994)

The very first episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, “Encounter at Farpoint” involves the Q (John De Lancie) trying Captain Picard (Patrick Stewart) and the command crew of the Enterprise for mankind’s “grievously savage” history. Picard suggests that the mystery of Farpoint station can prove that humanity has outgrown its savagery.

But another episode, “A Matter of Perspective” also features a trial. At the same time, it thoroughly rip-offs a cinema classic: Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950). The film tells the tale of two terrible, criminal acts: the rape and murder of a woman, and the death of her samurai husband. During the course of the film, the events of the rape and possible murder are recounted four times, from four different perspectives.

The first time the story is depicted, we see it as the bandit (Toshiro Mifune) — the accused — remembers the events. The next time, the rape victim, the samurai’s wife, recounts the story as she remembers it. Then, oddly, the story is recounted a third time by a supernatural medium who claims to be channeling the Samurai’s spirit. Finally, a kindly woodcutter — a legitimate eyewitness — tells the story, in the least biased presentation of the bunch.

One of the great and enduring qualities of Rashomon is that it artfully suggests that there is no such thing as objective truth. Eyewitnesses may be more or less impartial, but in the final analysis, everyone is a prisoner to his or her own sense of perspective. The stories depicted in the film are personal accounts that may be lies, but may also, simply, be how the percipients remembered them. Those memories may be self-serving, but aren’t all memories, at least to some degree, self-serving?

In “A Matter of Perspective,” jovial Commander Riker (Jonathan Frakes) is accused of murder after a visit to Botanica Four, a research space station over Tanuga Four. The victim is Dr. Apgar, who dies in an explosion right after Riker Captain Picard takes up Riker’s defense, and the story of Riker’s visit to the station — and his alleged entanglement with Apgar’s wife, Manua — is recreated several times using the holodeck.

In this case, we get the testimony of Cmdr. Riker, Dr. Apgar, and his female assistant. But disappointingly, and rather determinedly unlike the cinematic source material, the mystery on TNG is resolved without real questions of viewpoint or world view. We learn that one man, the victim (Apgar), was duplicitous and corrupt and that he brought on his unfortunate death himself.

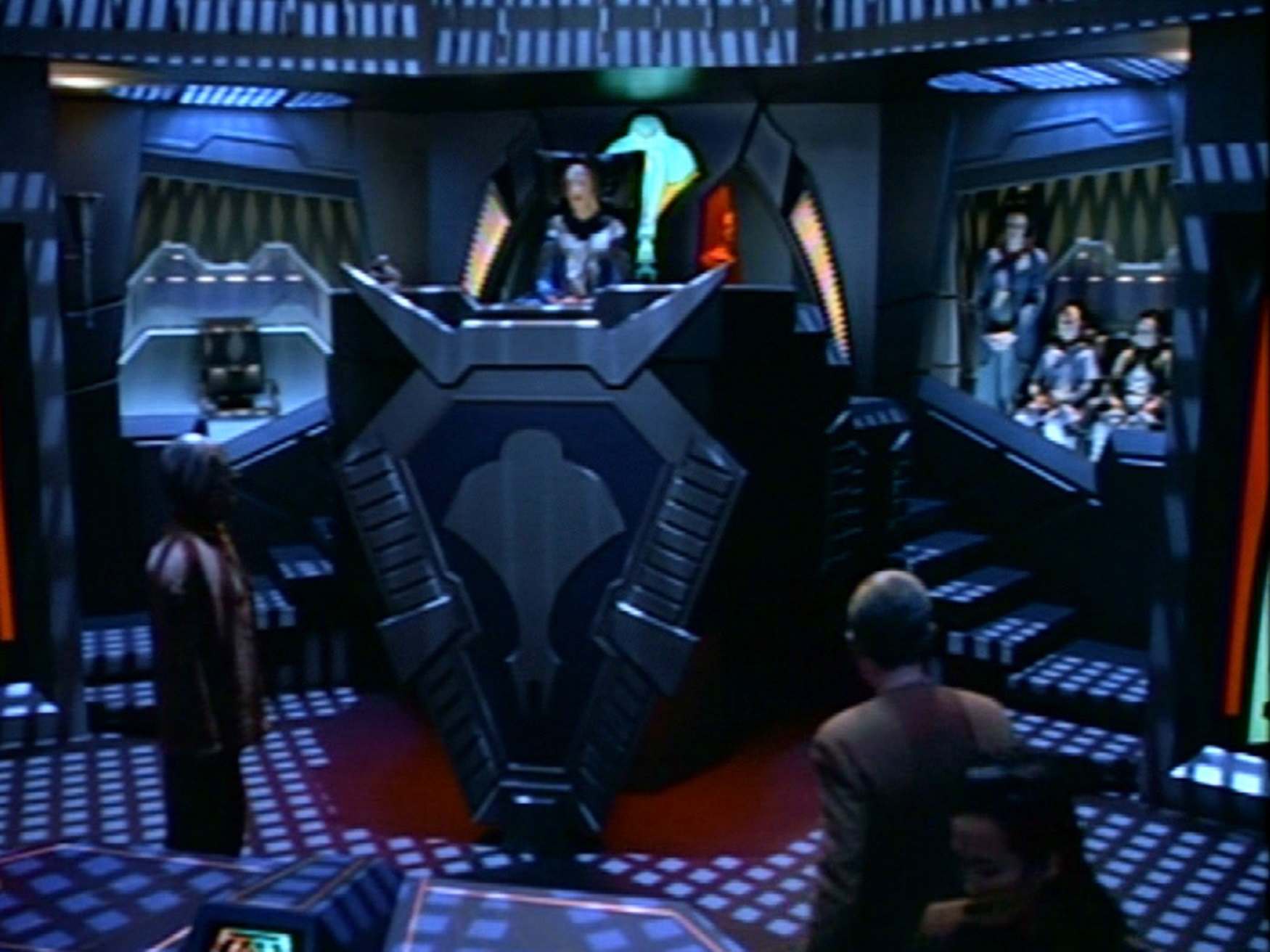

Mystery Science Theater 3000 (1989 – 1999)

Mike Nelson (himself) can’t run from the law during the host segments of the bad movie experiment Agent for H.A.R.M. Mike is taken from the space-going Satellite of Love by the Intergalactic Tribunal and charged with the destruction of three planets: Earth in the time of the Apes, The home-world of Brain Guy, or Observer, and a planet where Pearl Forrester (Mary Jo Pehl) camped out with Bobo (Kevin Murphy).

All hope seems lost for Mike, not only because he is guilty of destroying those planets, but because Bobo becomes his lawyer in court. Pearl, meanwhile, prosecutes…

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993 – 1999)

The Star Trek franchise takes on Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial (1925) in this story. In the literary work, a man named Josef K. is held for a trial, though he has committed no crime that he knows of, and the even the specific charges against him are nebulous and confusing.

In 1994’s “Tribunal,” Chief O’Brien (Colm Meaney) runs afoul of the Cardassian legal system, a Kafka-esque labyrinth in which the edict “guilty until proven innocent” thrives. He is captured and held for trial, while knowing nothing of what he has done, or the specifics of Cardassian law. Another heroic Starfleet officer, Commander Sisko (Avery Brooks) stepped in to prevent a miscarriage of justice and defend his friend, but the point of the story is that the law is a game, and a stacked game at that. It is impossible to defeat the system, unless the system has a motive for letting the defendant win (or escape).

Farscape (1999 – 2003)

In an episode that satirizes legal systems on Earth, Zhaan (Virginia Hey) is apprehended for murder on the planet “Litigaria,” where 90% of the population is employed as lawyers and law firms run the whole planet. If Zhaan loses in court, she will be executed in three days.

Fortunately, Rygel and Chiana agree to represent Zhaan in court, unaware that if they lose, they’ll face the same fate as their friend and client. Now it’s up to Ryglen to learn the totality of “Axiom,” a legal tome for the complicated and byzantine laws of Litigaria…

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.