Huey P. Newton was the co-founder of the Black Panther Party co-founder and Minister of Defense. He was born on February 17, 1942. He was murdered by a member of the Black Guerilla Family on August 22, 1989. On the way, one policeman was shot dead – Newton’s conviction for the murder of John Frey was overturned. When he was accused of killing Kathleen Smith, Newton fled to Cuba. He returned. Two trails failed to deliver a verdict. The case was dropped. So much for the violence. What about the message?

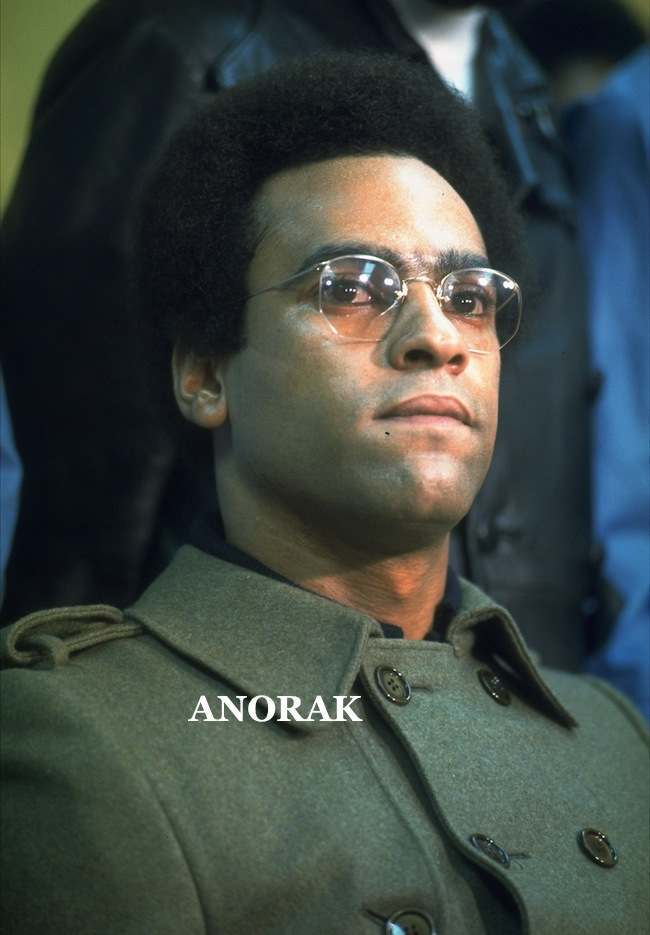

Photo above: This is an October 1971 photo of Black Panther chief Huey Newton in San Francisco after his return from a ten-day trip to China.

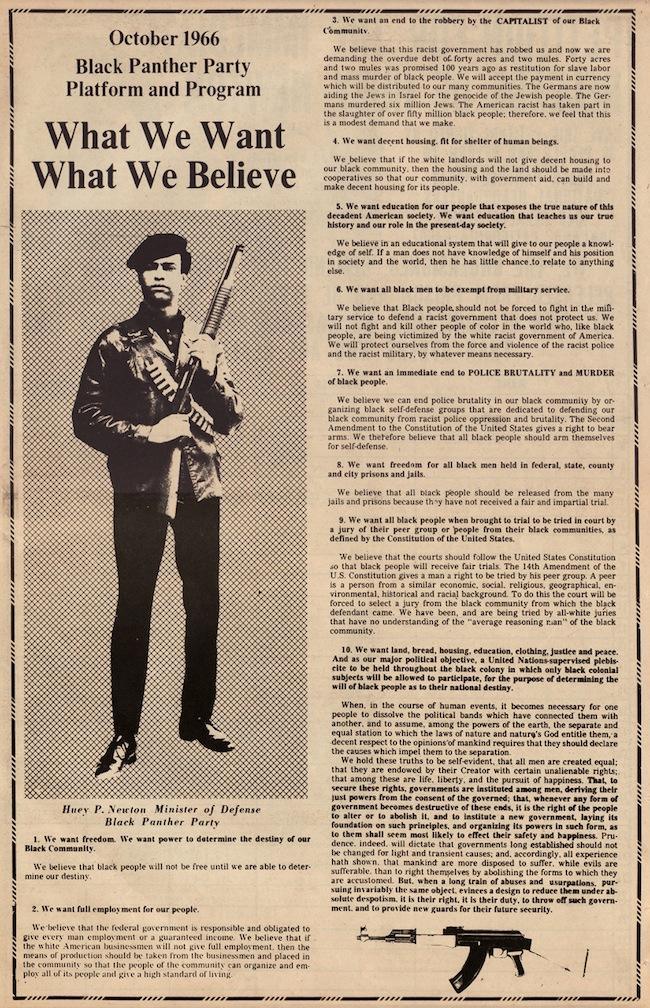

What did they want? Black Panther Party Platform. October, 1966:

The Rules:

The Founders: Bobby Seale and Huey Newton.

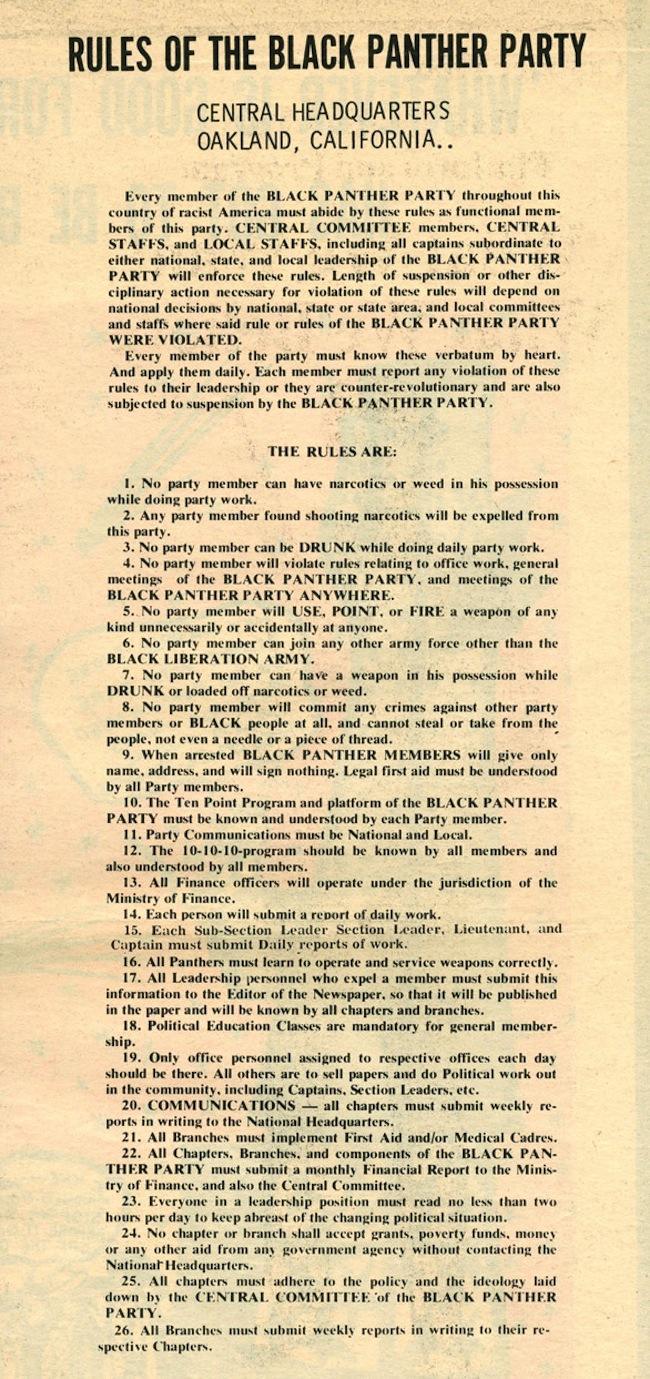

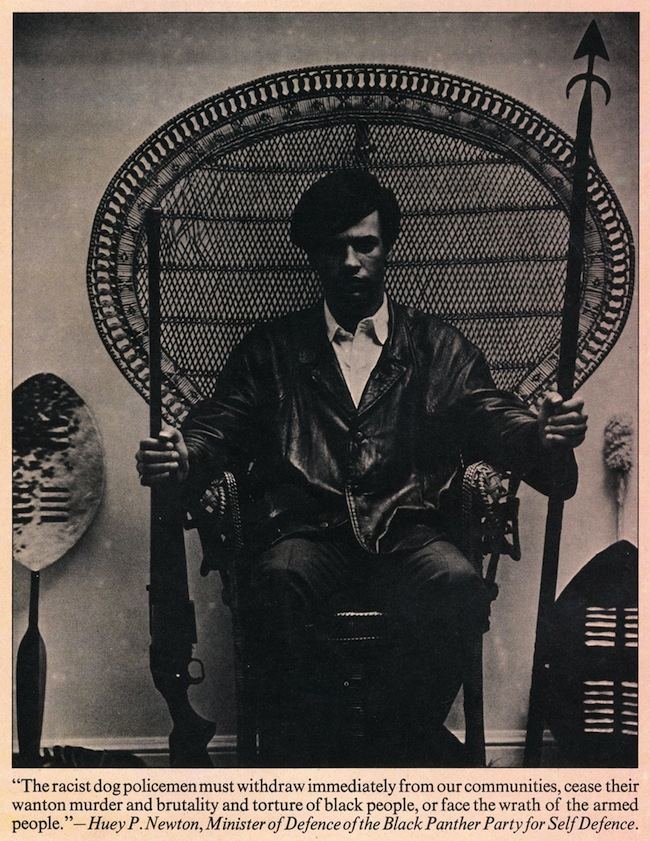

This scan is taken from the September 1967 issue of Ramparts magazine. It’s February 1967. Eldridge Cleaver, just two months out of prison, is working at Ramparts magazine, which began publishing his Soul on Ice essays while he was still locked up. Cleaver, not yet a Black Panther, is a part of an organization which is hosting Malcolm X’s widow Betty Shabazz for a series of Bay Area speaking engagements surrounding the second anniversary of Malcolm’s assassination. The newly formed, but already notorious, Black Panther Party for Self Defense is hired to provide security for Mrs. Shabazz while she is in the Bay Area.”

…it was at a meeting of the planning committee that Cleaver discovered the Black Panthers, only a few months after their formation. Newton and the others entered the storefront meeting place while Cleaver’s back was turned; he recalls the moment:

“From the tension showing on the faces of the people before me, I thought the cops were invading the meeting, but there was a deep female gleam leaping out of one of the women’s eyes that no cop who ever lived could elicit. I recognized that gleam out of the recesses of my soul, even though I had never seen it before in my life: the total admiration of a black woman for a black man. I spun ‘round in my seat and saw the most beautiful sight I had ever seen: four black men wearing black berets, powder-blue shirts, black leather jackets, black trousers, shiny black shoes—and each with a gun! In front was Huey P. Newton with a riot pump shotgun in his right hand, barrel pointed down to the floor. Beside him was Bobby Seale, the handle of a .45-caliber automatic showing from its holster on his right hip, just below the hem of his jacket. A few steps behind Seale was Bobby Hutton, the barrel of his shotgun at his feet. Next to him was Sherwin Forte, an M-1 carbine with a banana clip cradled in his arms…

Where was my mind at? Blown!”

As it turned out, the Panthers accepted responsibility for Mrs. Shabazz’s security during her visit to the Bay Area (there was some fear that she, too, might be assassinated). It led to a scene in San Francisco as strange as the one that had taken place outside Panther headquarters in Oakland—stranger, perhaps, for it took place not in a ghetto but in busy North Beach, alongside a freeway onramp, with television cameras on hand and a startled audience of passing commuters.

Hakim Jamal, a cousin by marriage to Malcolm X, had called Eldridge Cleaver at Ramparts to say that Mrs. Shabazz had read and liked an article and that she wanted to visit him; they agreed that she would come to the Ramparts office. I was there the day she arrived, and once the fear passed (I was convinced that one of the angry policemen on the scene would do something stupid, despite the obvious discipline of the Panthers), my mind, too, was blown.

What had happened, simply, was that about twenty Panthers, all armed, had escorted Jamal and Mrs. Shabazz from the airport to Ramparts. Airport police had challenged the Panthers, but had agreed that there was nothing illegal about their carrying loaded weapons; they did, however, call the San Francisco police, who arrived at Ramparts a few minutes after the Panthers.

While Cleaver talked with Jamal and Mrs. Shabazz, most of the Panthers stayed outside or just inside the lobby. Panthers, cops, outside newsmen, and Ramparts staffers made for an enormous traffic jam, but editor Warren Hinckle III kept insisting to the lieutenant in charge of the police that nothing was wrong, which made the lieutenant furious, and there were no incidents while the visitors were there, except that two of the younger staffers tossed out a television cameraman who forced his way into the office and refused to leave.

When the visit was completed, Newton, who had been outside Cleaver’s office, appeared in the lobby, sent five Panthers to clear a path through the crowd, surrounded Mrs. Shabazz and Jamal with ten more Panthers in a knot and rushed them into a car, and then, with Seale and three others, brought up the rear. The same television cameraman was taking pictures, and Newton held an envelope over the lens; the cameraman called him a name and knocked the envelope away with his fist. Newton turned to the nearest policeman.

“Officer, I want you to arrest this man for assault.”

The cop gaped. “If I arrest anyone, it’ll be you,” he finally shouted. Huey put the envelope up again, the cameraman knocked it away again, and Huey grabbed the cameraman’s collar and shoved him fifteen feet down the hill.

The cops spread out and poised, but otherwise did not move as the Panthers started for their car. Huey instructed the others not to turn their backs on the policemen; the order made one of them even angrier, and I, at least, thought the moment I feared had come when I saw him snap the cover open on his holster, and saw Huey spin to face him.

They stood for a moment until the cop said huskily, “Don’t point that gun at me!”

Newton, the barrel of his shotgun pointed, as it had been, at the sidewalk, asked him, “You want to draw your gun?”

Those of us who might be in the way got out of the way, police included; another cop said, “Take it easy, take it easy”—to his partner, not to Newton.

“Okay, you big fat racist pig,” Newton said deliberately, “draw your gun.”

They stood for another moment, Seale calling to Newton to leave while the other police called to their fellow to let the moment go. Then the policeman dropped his hands carefully to his sides and lowered his head. Newton laughed, turned his back, and walked to the car.

“Goddamn,” said Eldridge Cleaver, who was standing on the steps outside the Ramparts office, “that nigger is crazy!”

Later he wrote:

“The quality in Huey P. Newton’s character which I had seen that morning in front of Ramparts and which I was to see demonstrated over and over again after I joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was courage. I had called it ‘crazy,’ as people often do to explain away things they do not understand. I don’t mean the courage to stand up and be counted, or even the courage it takes to face certain death. I speak of that revolutionary courage it takes to pick up a gun with which to oppose the oppressor of one’s people. That’s a different kind of courage.”

Photo: Members of the Black Panthers gather in front of entrance to the Alameda County Courthouse in Oakland, Calif., July 15, 1968, to protest the trial of Huey Newton, 26, the founder of the Black Panthers. Newton went on trial for the slaying of an Oakland policeman and wounding another officer on October 28.

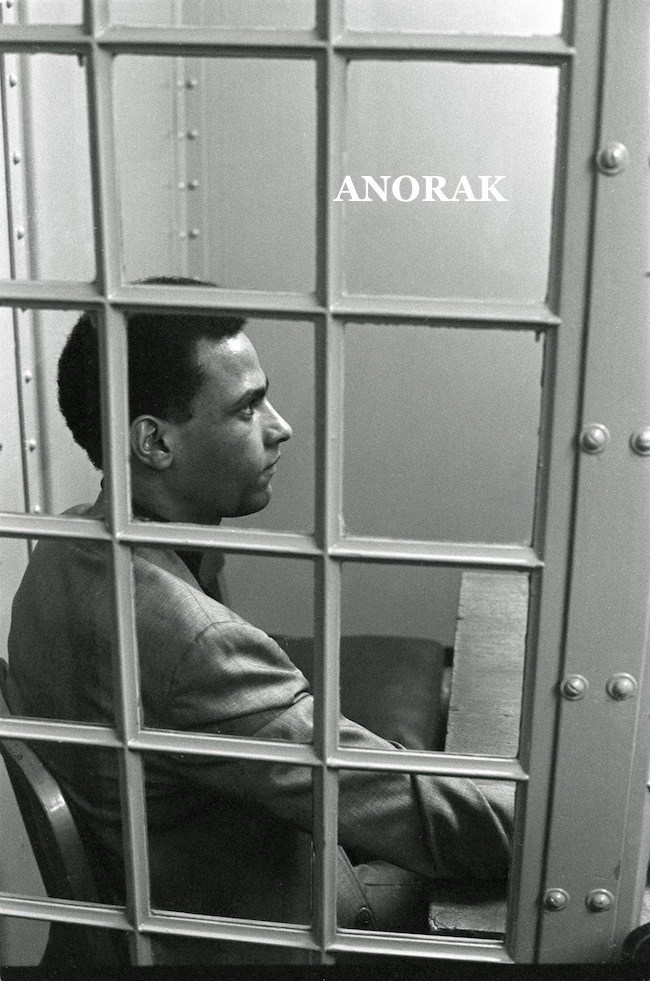

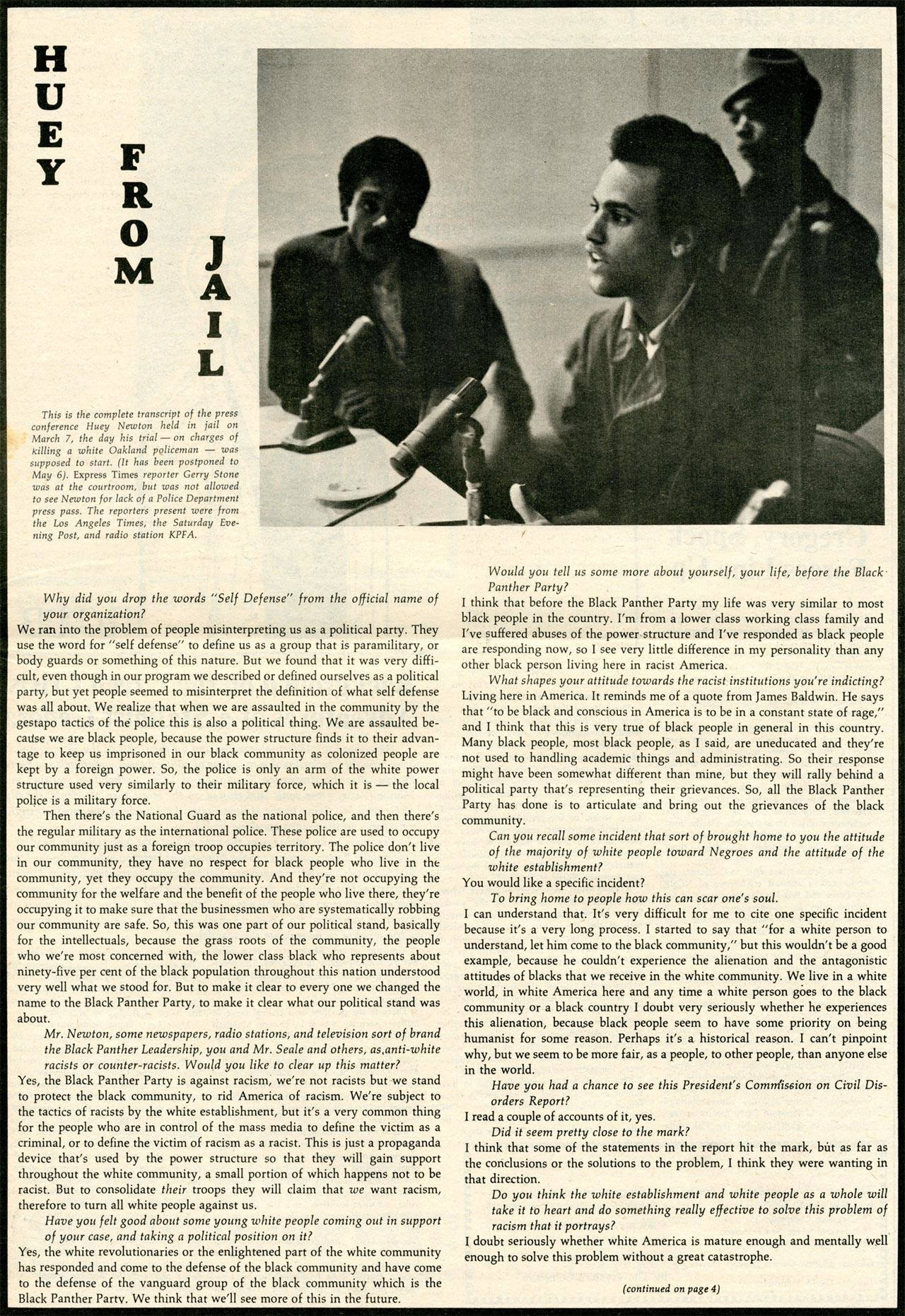

Photo: Black Panther leader Huey Newton gazes from a jail cell on the 10th floor of the Alameda County Courthouse in Oakland, Calif., July 18, 1968. Newton, 26, on trial for a white policeman’s slaying, had called the news conference to accuse his jailers of attempting to break his spirit.

He spoke from jail (click to enlarge):

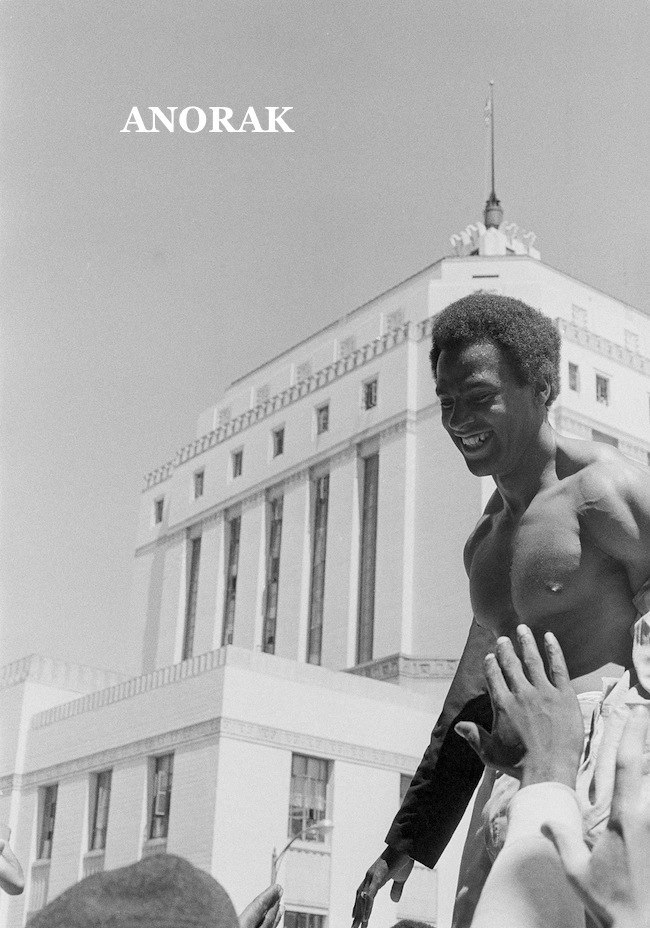

Photo: Stripped to the waist in the afternoon sun, Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panthers shakes hands with followers and friends who greeted him as he walked out of the Alameda County Courthouse in Oakland, Calif., Aug. 6, 1970. Newton is free on $50,000 bail pending retrial on voluntary manslaughter charges stemming from a 1967 fatal shooting of an Oakland policeman.

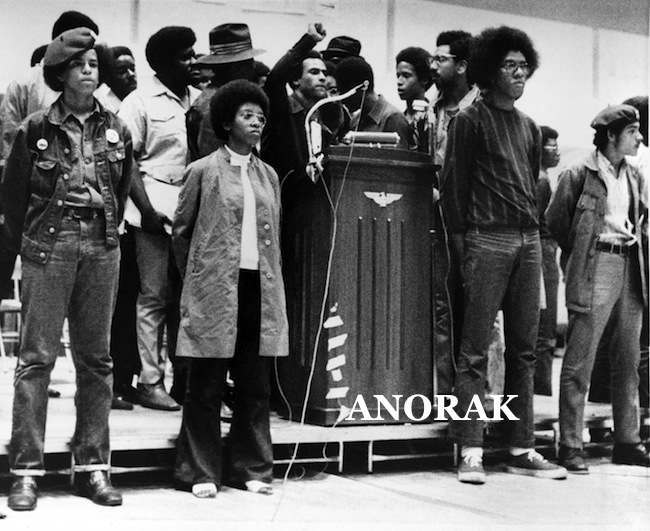

Photo: Huey P. Newton, national defense minister of the Black Panther Party, raises his clenched fist behind the podium as he speaks at a convention sponsored by the Black Panthers at Temple University’s McGonigle Hall in Philadelphia, Pa., Saturday, Sept. 5, 1970. He is surrounded by security guards of the movement. The audience gathered is estimated at 6,000 with another thousand outside the crowded hall.

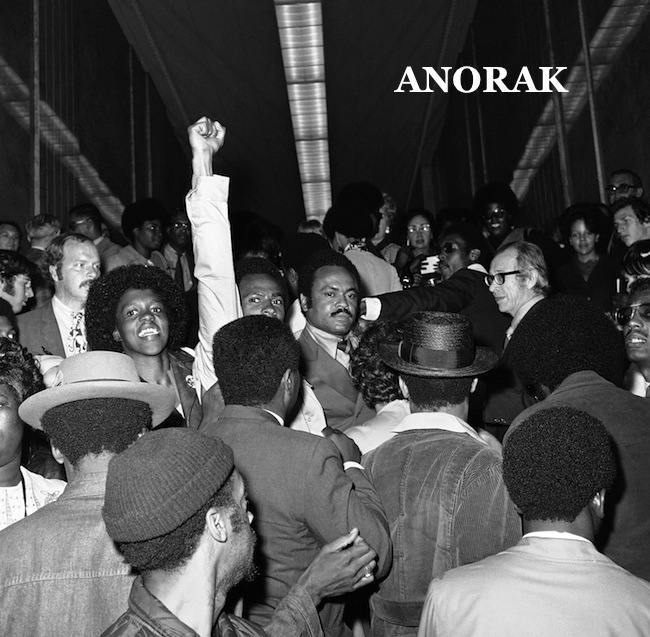

Photo: Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panthers, gestures as he talks to friends and followers from the top of an automobile in Oakland, Calif., Aug. 6, 1970, immediately after his release on $50,000 bail pending retrial on voluntary manslaughter charges stemming from the 1967 fatal shooting of an Oakland policeman. Standing behind Newton is David Hilliard, Black Panther who is charged with threatening the life of President Nixon.

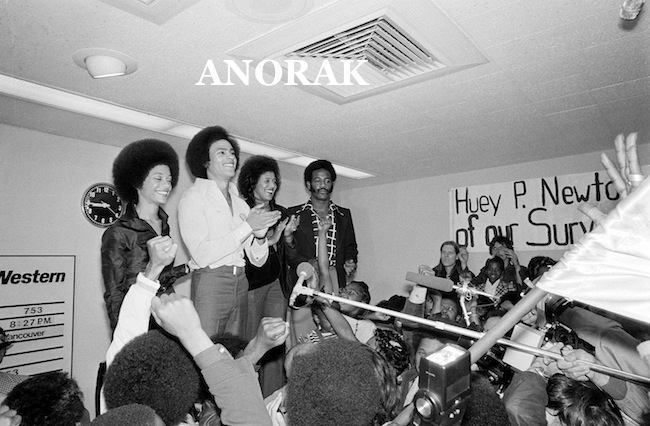

Photo: Black Panther leader Huey Newton stands atop a ticket counter at San Francisco International Airport to address a large crowd gathered to greet him, July 4, 1977. With Newton is his wife Gwen, left, and Black Panther chairperson Elaine Brown. Man at right is unidentified.

Guns are freedom:

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.