“Exaltation is a tremendous lucidity” (Le vertige est une lucidité formidable), particularly an exaltation carrying you simultaneously towards day and night, composed of two eddies turning into opposite directions. One sees too much and not enough. One sees everything, and nothing”

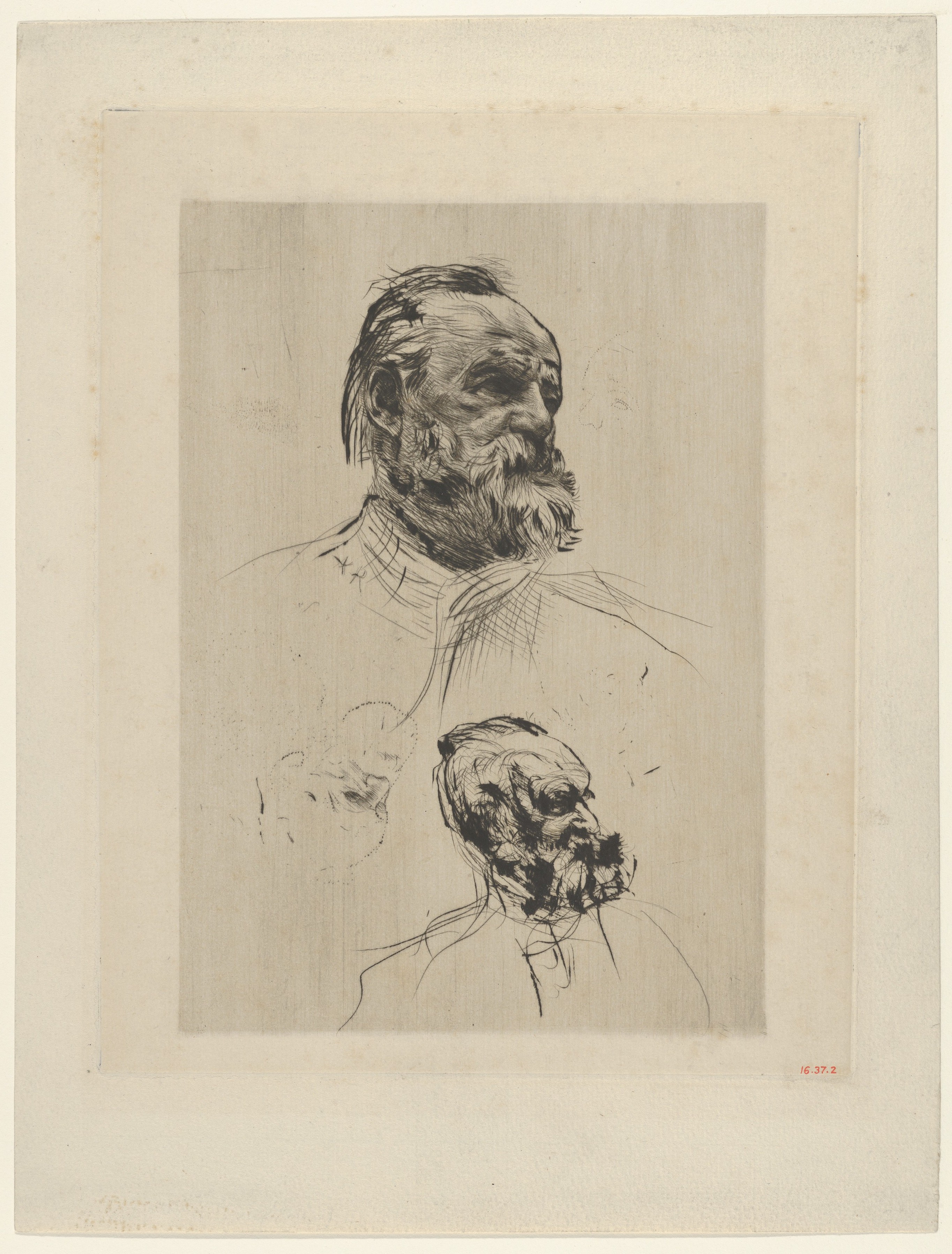

– Romantic poet and writer Victor Hugo (1802-1885)

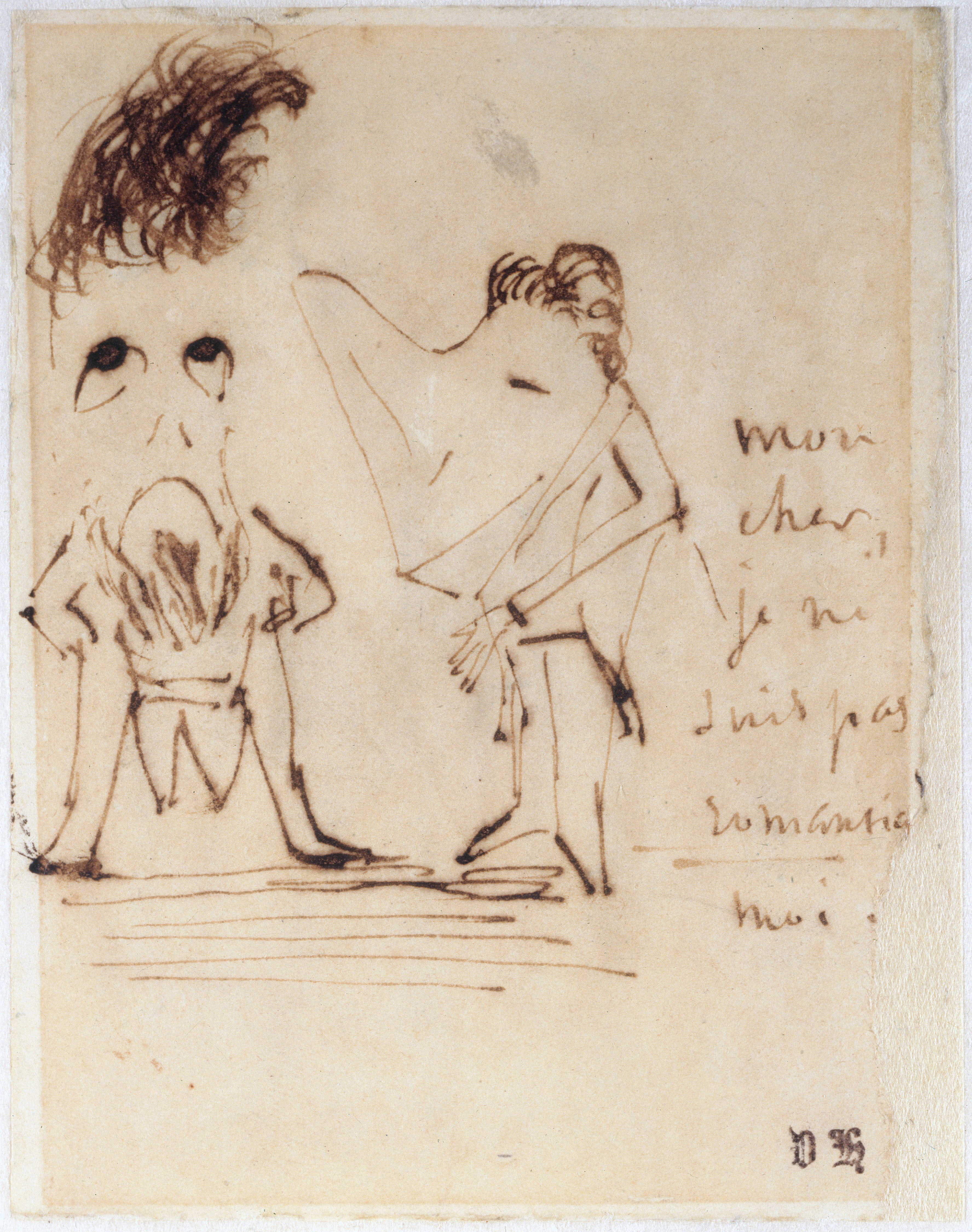

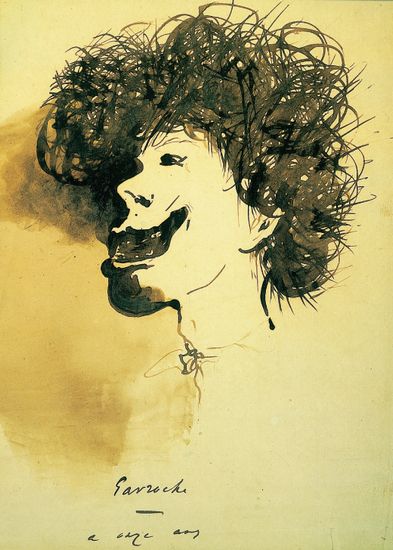

When not writing Les Misérables and photographing his life in exile on the British Channel Islands between 1852 and 1870, Victor Hugo drew for private pleasure. He’d test himself by drawing with his ‘wrong’ hand, and, when ink supplies waned, would sketch in coal dust, soot, coffee grounds and blood (his own).

Charles Hugo wrote of his father’s draftsmanship and abstract art (via):

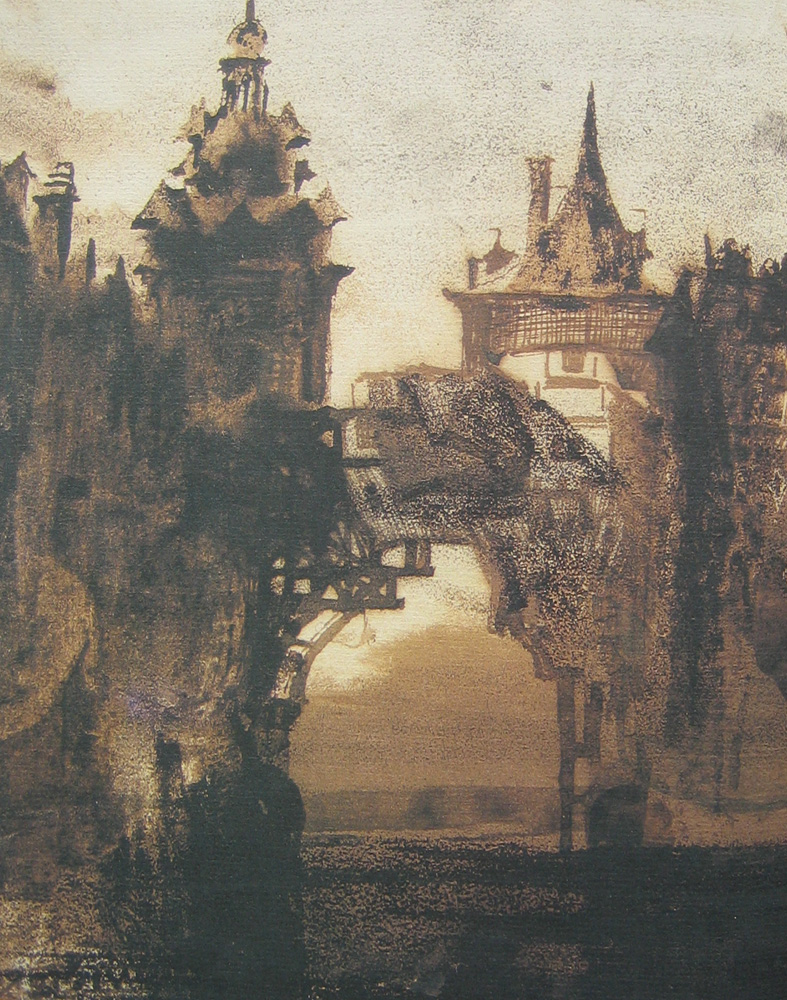

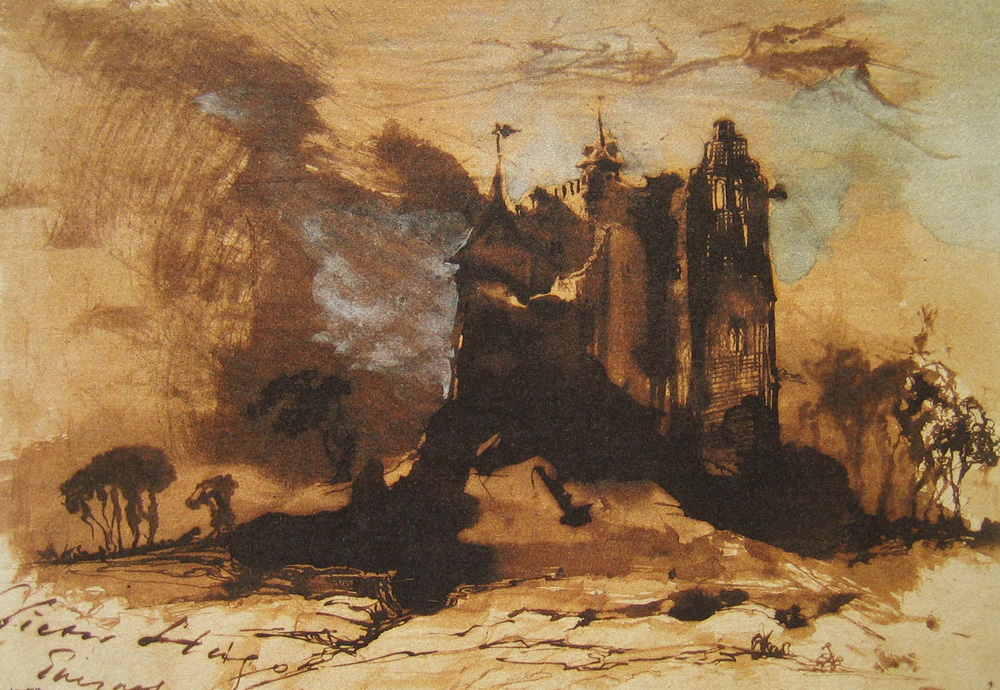

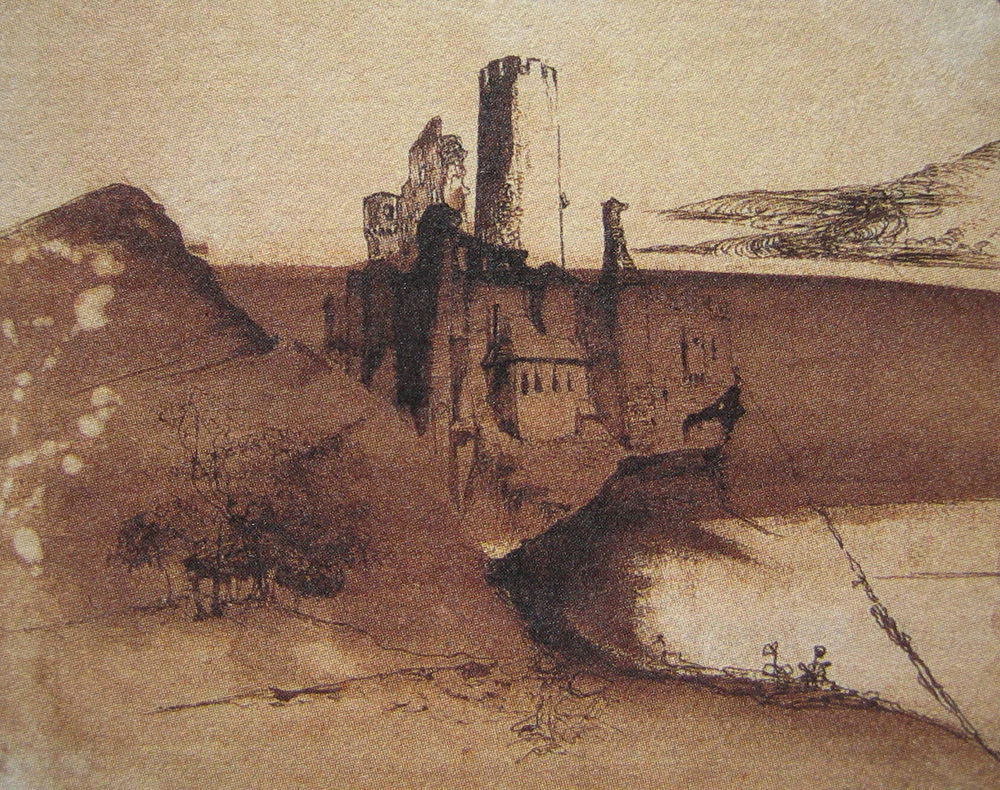

Once paper, pen, and inkwell have been brought to the table, [he] sits down and—without making a preliminary sketch, without any apparent preconception -sets about drawing with an extraordinarily sure hand: not the landscape as a whole, but any old detail. He will begin his forest with the branch of a tree, his town with a gable, his gable with a weathervane, and little by little, the entire composition will emerge from the blank paper with the precision and clarity of a photographic negative subjected to the chemical preparation that brings out the picture. That done, the draftsman will ask for a cup and will finish off his landscape with a light shower of black coffee. The result is an unexpected and powerful drawing that is often strange, always personal, and recalls the etchings of Rembrandt and Piranesi.

Victor Hugo (1802-1885). “Le Burg à la croix” (avec cadre). Plume et lavis d’encre brune, 1850. Paris, maison de Victor Hugo.

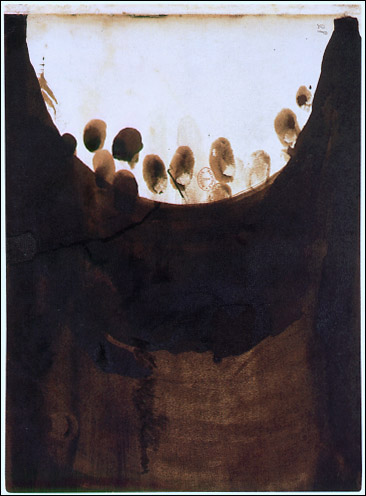

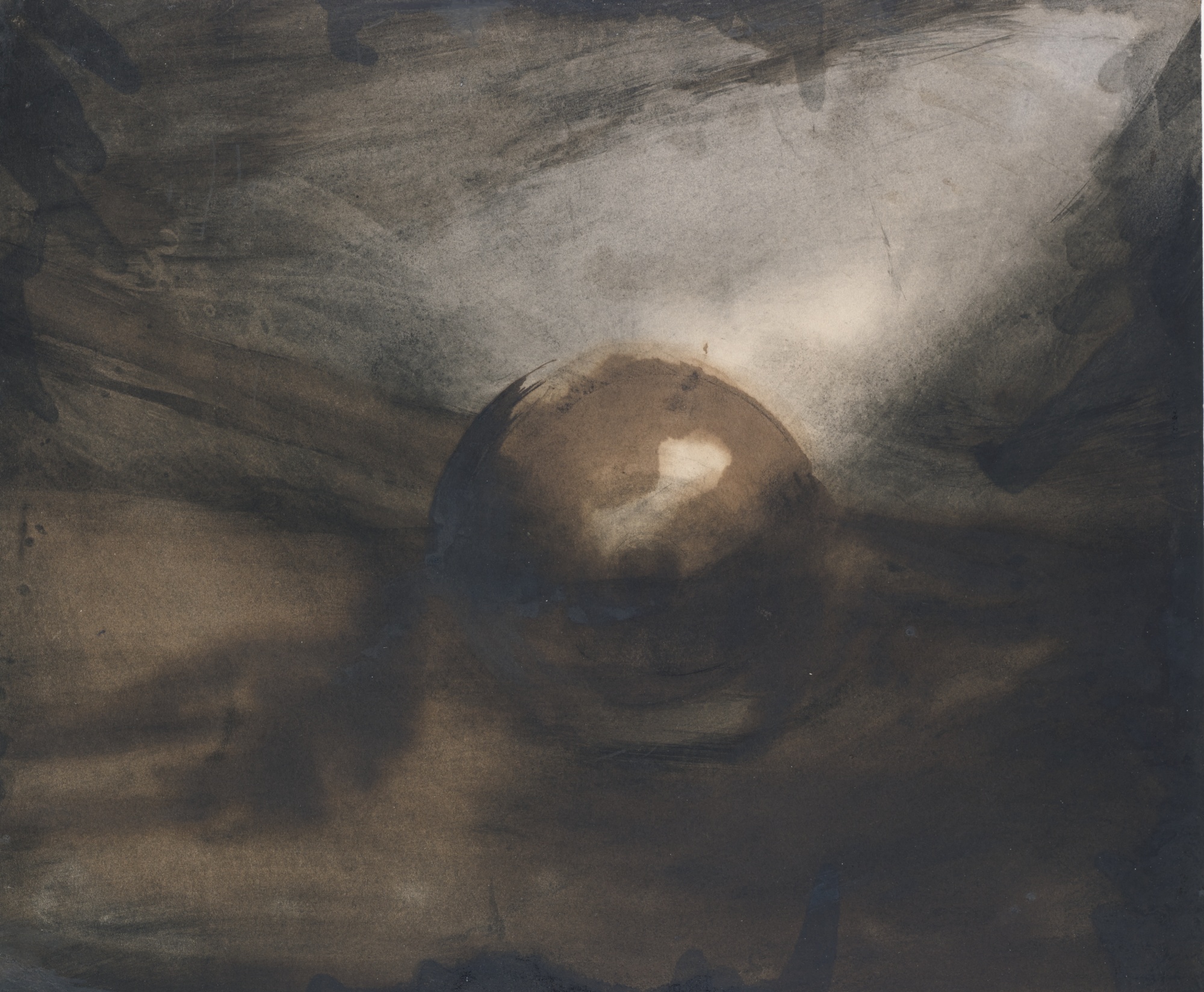

Hugo often began with a blot, as was the fashion of his age. Christopher Turner writes:

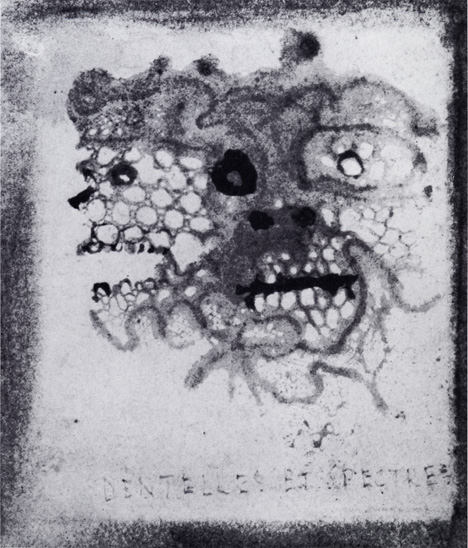

Blotto, which involved making random marks and decoding them, became a popular parlour game in the late 1850s. With its suggestion of the occult, it was as though, through random stains (as might be read in tea or coffee granules), the dead were in some way communicating with the assembled players. Victor Hugo was another enthusiastic amateur blotter, and in his ‘Tache’ or ‘stain’ paintings he shares [Justinus] Kerner’s predilection for gothic phantasmagoria. After his daughter Léopoldine tragically drowned in the Seine, Hugo used Ouija boards to try to communicate with her. He claimed to have been able to summon her ghost in seances, along with those of Dante, Galileo, Voltaire, Moses, Jesus Christ, Death and the ‘Ocean’, which flooded him with waves of expletives. Sometimes he would replace one of the legs of the planchette with a pencil, so that a spirit might communicate in a continuous line drawing as it moved the planchette around the board.

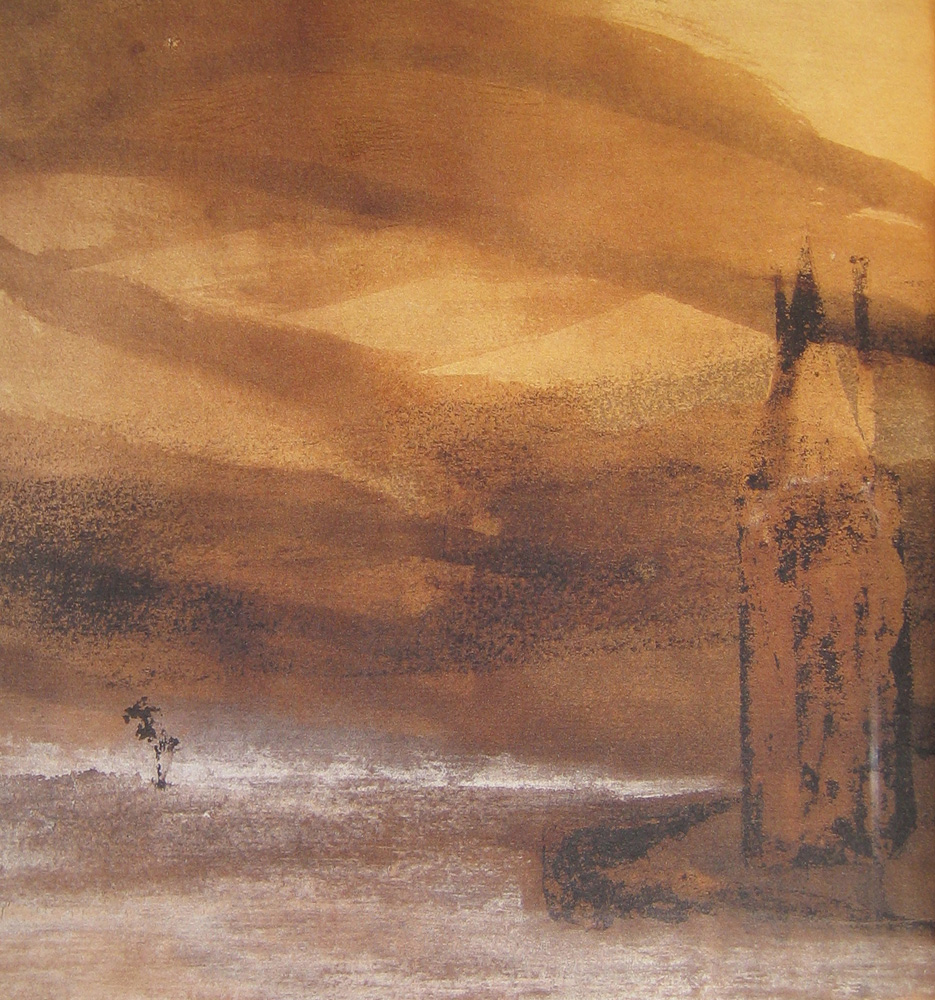

Hugo’s sophisticated blot-inspired pen-and-ink drawings were, he wrote, ‘for private use and to indulge very close friends’. The majority were created when he was in political exile in the Channel Islands, where he lived from 1851 to 1870 in protest at Napoleon III’s unlawful seizure of power: they depict shipwrecks, gallows, Piranesi-like staircases, haunted landscapes, spiky castles and crumbling cities in muddy, sepia tones, which seem to emerge from the page as though approached through thick fog.

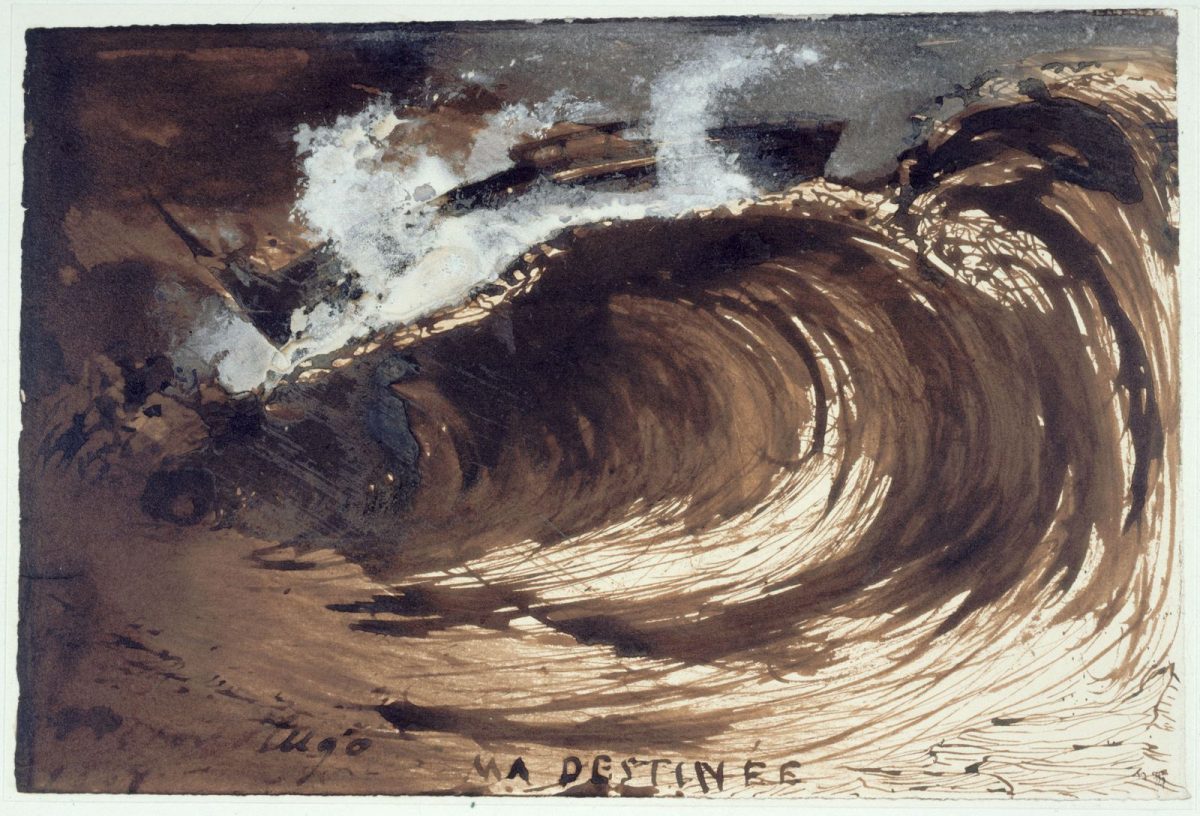

Hugo’s friend Philippe Burty said of his technique: ‘Any means would do for him – the dregs of a cup of coffee tossed on old laid paper, the dregs of an inkwell tossed on notepaper, spread with his fingers, sponged up, dried, then taken up with a thick brush or a fine one… Sometimes the ink would bleed though the notepaper, and so on the reverse another vague drawing was born.’ Hugo also folded the smudged paper to create abstract rosettes, and applied ink-soaked lace to create skeletal venations. A sense of threat lurks beneath the surface of much of his imagery. (It was rumoured that he used blood pricked from his own veins in his many drawings.) In one sketch a giant, menacing octopus, fashioned from a single stain, contorts its suckered limbs into the initials VH.

It is tempting to ascribe the mood of Hugo’s drawings to the tumult of these years. In an 1867 piece, a huge, frothy wave curls ominously into the sky, poised to crash at any moment. It is titled “Ma destinée”—My destiny. – Smithsonian

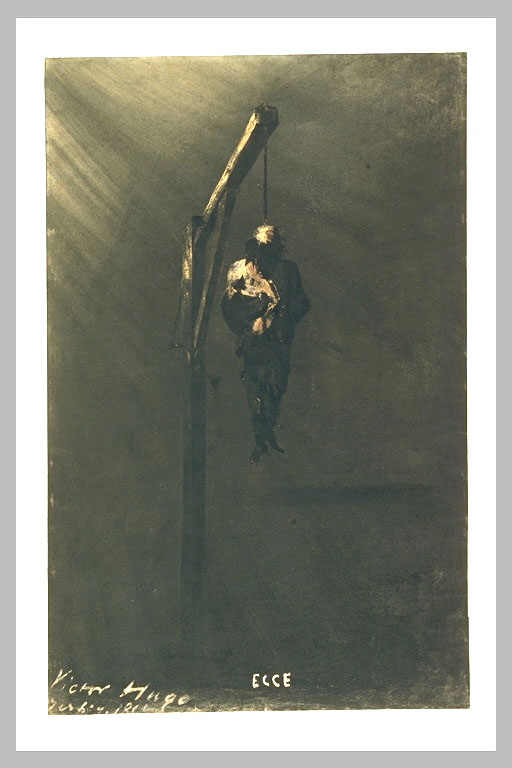

Hugo was ever spiritual. As Amy M. Martin writes on Hugo’s haunting image of the hanged man.

One of the works that has been stuck in my mind is Victor Hugo’s The Hanged Man (c. 1855-60)…. There is something solemn, even sacred, about this image to me, and I find it remarkable that such a simple composition created by a few strokes of the brush can convey such a profound sense of sorrow, hopelessness, loneliness, and loss. The only mourners that this man has in death are the birds flocking around his corpse.

I tried to resist the temptation to conduct a study of this image in order to bask in the mystery, but the historian in me had to know: Why was this man hung? Surely such a powerful image would not arise without a profound motivation; a catalyst from Hugo’s own life. Indeed, this is one of four drawings Hugo made depicting the horror of the gallows after witnessing an execution in the Channel Islands in 1854.

Five years later in 1859, Hugo urgently and passionately petitioned to save the life of John Brown, an American abolitionist sentenced to death.3 After false hope that Brown might be released, the abolitionist was hanged. Hugo mourned Brown’s death through the written word and art, creating a drawing which he titled Ecce — Behold. Ecce is a commanding image wherein the viewer is confronted with the injustice of Brown’s execution. A kind of divine light illuminates Brown, who otherwise hangs amidst still darkness, alone. He is a martyr.

Ecce challenged contemporary viewers to reconcile Brown’s horrific punishment with the righteousness of his cause. Those who knew Brown’s story would quickly realize that such a feat is impossible, for the punishment does not fit the crime. Hugo had Ecce distributed through prints, with proceeds from the sales going to various charities, “including those to provide medical supplies to soldiers in the Civil War.”

Victor Hugo in Exile:

He was ennobled and elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe in 1845 and entered the Higher Chamber as a pair de France, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favour of freedom of the press and self-government for Poland.

In 1848, Hugo was elected to the National Assembly of the Second Republic as a conservative. In 1849, he broke with the conservatives when he gave a noted speech calling for the end of misery and poverty. Other speeches called for universal suffrage and free education for all children. Hugo’s advocacy to abolish the death penalty was renowned internationally.

These parliamentary speeches are published in Œuvres complètes: actes et paroles I : avant l’exil, 1841–1851. Scroll down to the Assemblée Constituante 1848 heading and subsequent pages.[14]

When Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) seized complete power in 1851, establishing an anti-parliamentary constitution, Hugo openly declared him a traitor to France. He relocated to Brussels, then Jersey, from which he was expelled for supporting a Jersey newspaper that had criticised Queen Victoria and finally settled with his family at Hauteville House in Saint Peter Port, Guernsey, where he would live in exile from October 1855 until 1870.

“Ah! you’re familiar with my daubings? They are not, I would say, at too presumptuous a remove from my main line of work, since I make them with two ends of my only instrument, that is to say by drawing with the nib of a goose quill and painting with the bristles of the barb.” – Victor Hugo

“Anything that furthers the great aim, Liberty, is a duty as far as I am concerned, and I shall be happy if this drawing, reproduced many times over by your art, helps keep ever-present in people’s souls the memory of this liberator of our black brethren…” – Victor Hugo writing to engravor Paul Chenay.

“I am very happy and very proud that you should choose to think kindly of what I call my pen-and-ink drawings. I’ve ended up mixing in pencil, charcoal, sepia, coal dust, soot and all sorts of bizarre concoctions which manage to convey more or less what I have in view, and above all in mind. It keeps me amused between two verses.” -Victor Hugo in a letter to Baudelaire, April 29, 1860.

Victor Hugo (1802-1885). “La tour des rats”. Plume et lavis d’encre brune, 27 septembre 1840. Paris, maison de Victor Hugo. Dimensions : 28,5 x 44,8

On Hugo’s expression of free thinking in captivity, Maria Popova writes:

In the fall of 1830, Victor Hugo set out to write The Hunchback of Notre Dame against the seemingly impossible deadline of February 1831. He bought an entire bottle of ink in preparation and practically put himself under house arrest for months, using a most peculiar anti-escape technique:

Hugo locked away his clothes to avoid any temptation of going outside and was left with nothing to wear except a large gray shawl. He had purchased the knitted outfit, which reached right down to his toes, just for the occasion. It served as his uniform for many months.

He finished the book weeks before deadline, using up the whole bottle of ink to write it. He even considered titling it What Came Out of a Bottle of Ink, but eventually settled for the less abstract and insidery title.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.